| Revision as of 02:02, 27 September 2012 editDoors22 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users624 editsm Fixed formatting← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:06, 27 September 2012 edit undoBiosthmors (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Pending changes reviewers18,952 edits revert. political advocates do not get to decide what adverse affects are per WP:MEDRS -- they are not reliable medical sourcesNext edit → | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

| ===Teratogenicity=== | ===Teratogenicity=== | ||

| Finasteride is in the FDA ] X. This means that it is known to cause ] in a ]. Women who are or who may become pregnant must not handle crushed or broken finasteride tablets, because the medication could be absorbed through the skin. Finasteride is known to cause birth defects in a developing male baby. Exposure to whole tablets should be avoided whenever possible, however exposure to whole tablets is not expected to be harmful as long as the tablets are not swallowed. It is not known whether finasteride passes into ], and thus should not be taken by breastfeeding women. Finasteride may pass into the ] of men, but Merck states that a pregnant woman's contact with the semen of a man taking finasteride is not an issue for concern. Finasteride is known to affect blood donations, and potential donors are typically restricted for at least a month after their most recent dose.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fda.gov/Cber/bldmem/072893.pdf|title=FDA guidance on blood donors and medications|publisher=]|accessdate=01-02-2009|format=pdf |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20051031172818/http://www.fda.gov/Cber/bldmem/072893.pdf |archivedate = October 31, 2005}}</ref> | Finasteride is in the FDA ] X. This means that it is known to cause ] in a ]. Women who are or who may become pregnant must not handle crushed or broken finasteride tablets, because the medication could be absorbed through the skin. Finasteride is known to cause birth defects in a developing male baby. Exposure to whole tablets should be avoided whenever possible, however exposure to whole tablets is not expected to be harmful as long as the tablets are not swallowed. It is not known whether finasteride passes into ], and thus should not be taken by breastfeeding women. Finasteride may pass into the ] of men, but Merck states that a pregnant woman's contact with the semen of a man taking finasteride is not an issue for concern. Finasteride is known to affect blood donations, and potential donors are typically restricted for at least a month after their most recent dose.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fda.gov/Cber/bldmem/072893.pdf|title=FDA guidance on blood donors and medications|publisher=]|accessdate=01-02-2009|format=pdf |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20051031172818/http://www.fda.gov/Cber/bldmem/072893.pdf |archivedate = October 31, 2005}}</ref> | ||

| ===Post-Finasteride-Syndrome Foundation=== | |||

| In July 2012, the PFS foundation was launched which is dedicated to funding research on the characterization of underlying biologic mechanisms and treatments of post-finasteride syndrome (PFS). Post-finasteride-syndrome is characterized by sexual, neurological, hormonal and psychological side effects that can persist in men who have taken finasteride for hair loss or an enlarged prostate. A secondary goal of the foundation is to help increase public awareness of PFS. The Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation is headed by Dr. John Santmann (CEO), an emergency department physician.<ref><http://www.pfsfoundation.org/about-post-finasteride-syndrome-foundation/></ref><ref><http://afr.com/p/lifestyle/mens_health/looking_at_care_with_critical_eye_ZRbAzUV4cRxZhspW7YRwBJ></ref> | |||

| ===Interference with doping assays=== | ===Interference with doping assays=== | ||

Revision as of 02:06, 27 September 2012

Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Proscar |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a698016 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 63% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | Elderly: 8 hours Adults: 6 hours |

| Excretion | Feces (57%) and urine (39%) as metabolites |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.149.445 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H36N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 372.549 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

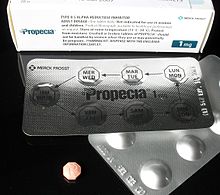

Finasteride (brand names Proscar and Propecia by Merck, among other generic names) is a synthetic type-2 5α-reductase inhibitor. This enzyme converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Finasteride is approved for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and male pattern baldness (MPB).

Medical uses

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Physicians use finasteride for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), informally known as an enlarged prostate. The approved dose is 5 mg once a day, and 6 months or more of treatment with finasteride may be required to determine the therapeutic results of treatment. If the drug is discontinued, any therapeutic benefits reverse within about 6-8 months. Finasteride may improve the symptoms associated with BPH such as difficulty urinating, getting up during the night to urinate, hesitation at the start of urination, and decreased urinary flow.

Male pattern baldness

In a 5-year study of men with mild to moderate hair loss, 2 out of 3 of the men who took 1 mg of finasteride daily regrew some hair, as measured by hair counts. In contrast, all of the men in the study who were not taking finasteride lost hair. In the same study, based on photographs that were reviewed by an independent panel of dermatologists, 48% of those treated with finasteride experienced visible regrowth of hair, and a further 42% had no further loss. Average hair count in the treatment group remained above baseline, and showed an increasing difference from hair count in the placebo group, for all five years of the study. Finasteride is effective only for as long as it is taken; the hair gained or maintained is lost within 6–12 months of ceasing therapy. In clinical studies, finasteride, like minoxidil, was shown to work on both the crown area and the hairline, but is most successful in the crown area.

Some users, in an effort to save money, buy Proscar (finasteride 5 mg) instead of Propecia, and split the Proscar pills into several parts to approximate the Propecia dosage. The pills are coated to prevent contact with the active ingredient during handling, and the dust or crumbs from broken Proscar tablets should be kept away from pregnant women or women who may become pregnant.

Off-label uses

Finasteride is sometimes used in hormone replacement therapy for male-to-female transsexuals in combination with a form of estrogen due to its antiandrogen properties. However, little clinical research of finasteride use for this purpose has been conducted and evidence of efficacy is limited. Indeed, finasteride is a substantially weaker antiandrogen in comparison to conventional antiandrogens like spironolactone and cyproterone. Furthermore, it has been associated with inducing depression and anxiety at a high rate in both male and female patients, symptoms that are very common in transsexuals and in whom are already at a high risk for. As a result, prescription of finasteride for this indication in male-to-female transsexuals may not be particularly useful, and could put them at risk for detrimental emotional side effects.

Adverse effects

Side effects of finasteride include impotence (1.1% to 18.5%), abnormal ejaculation (7.2%), decreased ejaculatory volume (0.9% to 2.8%), abnormal sexual function (2.5%), gynecomastia (2.2%), erectile dysfunction (1.3%), ejaculation disorder (1.2%) and testicular pain. According to the product package insert, resolution occurred in men who discontinued therapy with finasteride due to these side effects and in most men who continued therapy. The PPI also states that patients have reported persisting erectile dysfunction despite discontinuing the drug. In December 2010, Merck added depression as a side effect of finasteride.

Prostate cancer

The FDA has added a warning to finasteride concerning an increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer. While the effect of finasteride on the risk of developing prostate cancer has not been established, evidence suggests it may temporarily reduce the growth and prevalence of benign prostate tumors, but could also mask the early detection of prostate cancer. The primary concern is patients who develop prostate cancer while taking finasteride for benign prostatic hyperplasia, which in turn could delay diagnosis and early treatment of the prostate cancer, thereby potentially increasing the risk of these patients developing high-grade prostate cancer.

The 2005 Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) showed at a dosage of 5 mg per day, as is commonly prescribed for BPH, participants taking finasteride were 25% less likely to have developed prostate cancer at the end of the trial compared to those taking a placebo. It appeared (incorrectly) that finasteride increased the specificity and selectivity of prostate cancer detection, thus creating an apparently increased rate of high Gleason grade tumor. A 2008 update of this study found that finasteride reduces the incidence of prostate cancer by 30%. In the original study, the smaller prostate caused by finasteride facilitated detection of cancer nests and aggressive-looking cells. Most of the men in the study who had both low and high-grade prostate cancer chose to be treated, and many had their prostates removed. A pathologist then carefully examined each of those 500 prostates and compared the kinds of cancers found at surgery to those initially diagnosed at biopsy. This study concluded that finasteride did not increase the risk of high-grade prostate cancer.

Sexual side effects

There are case reports of persistent diminished libido or erectile dysfunction, even after stopping the drug. In December 2008, the Swedish Medical Products agency concluded a safety investigation of finasteride and advised that finasteride may cause irreversible sexual dysfunction. The Agency's updated safety information lists difficulty in obtaining an erection that persists indefinitely, even after the discontinuation of finasteride, as a possible side effect of the drug. The UK's Medical and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) cites reports of erectile dysfunction that persists once use of finasteride has stopped. Similar labeling changes have been made by the Italian government. For a period of time there was a discrepancy between European and North American warning labels regarding the risks of developing persistent sexual side effects from taking Propecia but after two years in April 2011 Merck revised the United States' warning in consumer and medical leaflets to include erectile dysfunction that may persist after stopping finasteride. In April 2012, the FDA chose to approve Merck's proposal from 2011 only after the warning label was further strengthened to include reports of persistent libido disorders, ejaculation disorders, orgasm disorders, and decreased libido.

Anxiety and depression

Finasteride has been found to robustly induce anxious and depressive behaviors in animals. Accordingly, its clinical use has been associated with depression and anxiety in both men and women in at least several reports in the medical literature. In one study, at a dose of 1 mg per day, finasteride induced moderate to severe depression in 19 of 23 or 83% of participants, notably including all of the female patients. In addition, marked anxiety occurred comorbidly with the depressive symptoms in some cases. Another study with a larger sample size of 128 men, though no women, also at a dose of 1 mg per day, found that finasteride increased both BDI and HADS depression scores significantly. It also increased HADS anxiety scores, though this was not found to be statistically significant. The authors concluded that finasteride should be prescribed cautiously to patients at a high risk of depression.

In late 2010, Merck revised the label of its Propecia formulation of finasteride in the United States and Canada to add depression to the list of possible side effects.

Male breast cancer

In December 2009, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the UK announced new drug safety advice on finasteride and the potential risk of male breast cancer. The agency concluded that, although overall incidence of male breast cancer in clinical trials for finasteride 5 mg was not significantly increased, a higher risk of male breast cancer with finasteride use cannot be excluded. A warning on this risk will be included in the product information. Merck revised the United States' warning in consumer and medical leaflets to include the risk of male breast cancer.

Teratogenicity

Finasteride is in the FDA pregnancy category X. This means that it is known to cause birth defects in a fetus. Women who are or who may become pregnant must not handle crushed or broken finasteride tablets, because the medication could be absorbed through the skin. Finasteride is known to cause birth defects in a developing male baby. Exposure to whole tablets should be avoided whenever possible, however exposure to whole tablets is not expected to be harmful as long as the tablets are not swallowed. It is not known whether finasteride passes into breast milk, and thus should not be taken by breastfeeding women. Finasteride may pass into the semen of men, but Merck states that a pregnant woman's contact with the semen of a man taking finasteride is not an issue for concern. Finasteride is known to affect blood donations, and potential donors are typically restricted for at least a month after their most recent dose.

Interference with doping assays

Many sports organizations have banned finasteride because it can be used to mask steroid abuse. Since 2005, finasteride has been on the World Anti-Doping Agency's list of banned substances. However, it was removed from the list in 2009. Notable athletes who used finasteride for hair loss and were banned from international competition include skeleton racer Zach Lund, bobsledder Sebastien Gattuso, footballer Romário and ice hockey goaltender José Théodore.

Mechanism of action

Testosterone in males is produced primarily in the testicles, but also in the adrenal glands. The majority of testosterone in the body is bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), a protein produced in the liver that transports testosterone through the bloodstream, prevents its metabolism, and prolongs its half-life. Once it becomes unbound from SHBG, free testosterone can enter cells throughout the body. In certain tissues, notably the scalp, skin, and prostate, testosterone is converted into 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by the enzyme 5α-reductase. DHT is a more powerful androgen than testosterone (as it has approximately 3-10x the potency at the androgen receptor, the site of action of the androgen hormones), so 5α-reductase can be thought to amplify the androgenic effect of testosterone in the tissues in which it's found.

Finasteride, a 4-azasteroid and analogue of testosterone, works by acting as a potent and specific, competitive inhibitor of one of the two subtypes of 5α-reductase, specifically the type II isoenzyme. In other words, it binds to the enzyme and prevents endogenous substrates such as testosterone from being metabolized. 5α-reductase type I and type II are responsible for approximately one-third and two-thirds of DHT production in the body, respectively. Accordingly, finasteride selectively prevents the conversion of testosterone into DHT by the type II isoenzyme, resulting in a decrease in serum DHT levels by about 65-70% and in prostate DHT levels by up to 85-90%, where expression of the type II isoenzyme dominates. Unlike dual inhibitors of both isoenzymes of 5α-reductase which can reduce DHT levels in the entire body by more than 99%, finasteride cannot completely suppress DHT production because it lacks significant inhibitory effects on the 5α-reductase type I isoenzyme, possessing approximately 100-fold less affinity for it compared to type II. In addition to blocking the 5α-reductase type II isoenzyme, finasteride is a competitive inhibitor of the 5β-reductase type II isoenzyme, though this is not believed to play any role in its effects on androgen metabolism.

By blocking DHT production, finasteride reduces androgenic activity in the scalp, treating hair loss at its hormonal source. In the prostate, inhibition of 5α-reductase leads to a reduction of prostate volume, which improves the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and reduces the risk of prostate cancer. Inhibition of 5α-reductase also leads to a reduction in the weight of the epididymis and a decrease in the percentage of motile and morphologically normal spermatozoa found in the epididymis.

Cause of mood-related and sexual side effects

DHT, and neuroactive steroids (NAs) such as allopregnanolone (ALLO) and tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC), potent positive allosteric modulators of the GABAA receptor—which is the same site of action of euphoriant and anxiolytic drugs like benzodiazepines and alcohol), are important endogenous neuroregulators that have been shown to possess powerful antidepressant and anxiolytic effects as well as to play a positive role in sexual function. Their biosynthesis is dependent on both isoforms of 5α-reductase, and accordingly, finasteride has been shown to reduce their formation in the body. As such, this effect of finasteride is a likely cause of the emotional and sexual side effects associated with the drug. Additionally, due to the fact that the NAs and not just DHT are involved, the fact that the mood and anxiety-related side effects occur not only in men but in women as well can also potentially be explained.

Preparations

Drug trade names include Propecia and Proscar, the former marketed for male pattern baldness (MPB) and the latter for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), both are products of Merck & Co. There is 1 mg of finasteride in Propecia and 5 mg in Proscar. Merck's patent on finasteride for the treatment of BPH expired on June 19, 2006. Merck was awarded a separate patent for the use of finasteride to treat MPB. This patent is set to expire in November 2013.

Some studies have shown that the dose of finasteride needed to treat male pattern baldness may be smaller than 1 mg. Petitions to the FDA to re-examine the approved dosage in light of the statistical evidence and possible long-term risks, were met with the response that a study had shown increased effect of a 1 mg dose compared to 0.2 mg without added risks; the same study also concluded that doses of 0.01 mg per day were found to be ineffective in treating hair loss.

Chemical synthesis

Finasteride is synthesized from progesterone:

History

In 1974, Julianne Imperato-McGinley of Cornell Medical College in New York attended a conference on birth defects. She reported on a group of hermaphroditic children in the Caribbean who appeared sexually ambiguous at birth, and were initially raised as girls, but then grew external male genitalia and other masculine characteristic post-onset of puberty. Her research group found that these children shared a genetic mutation, causing deficiency of the 5α-reductase enzyme and male hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which was found to have been the etiology behind abnormalities in male sexual development. Upon maturation, these individuals were observed to have smaller prostates which were underdeveloped, and were also observed to lack incidence of male pattern baldness.

In 1975, copies of Imperato-McGinley's presentation were seen by P. Roy Vagelos, who was then serving as Merck's basic-research chief. He was intrigued by the notion that decreased levels of DHT led to the development of smaller prostates. Dr. Vagelos then sought to create a drug which could mimic the condition found in the pseudo-hermaphroditic children in order to treat older men who were suffering from benign prostatic hyperplasia.

In 1992, finasteride (5 mg) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which Merck marketed under the brand name Proscar.

In 1997, Merck was successful in obtaining FDA approval for a second indication of finasteride (1 mg) for treatment of male pattern baldness (MPB), which was marketed under the brand name Propecia.

See also

- Dutasteride, related 5-alpha reductase inhibitor.

References

- Edwards, Jayne E; Moore, R Andrew (2002). "Finasteride in the treatment of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review of randomised trials". BMC Urology. 2: 14. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-2-14. PMC 140032. PMID 12477383.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Rossi S (Ed.) (2004). Australian Medicines Handbook 2004. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0-9578521-4-2.

- Leyden, James; Dunlap, Frank; Miller, Bruce; Winters, Peter; Lebwohl, Mark; Hecker, David; Kraus, Stephen; Baldwin, Hilary; Shalita, Alan (1999). "Finasteride in the treatment of men with frontal male pattern hair loss". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 40 (6 Pt 1): 930–7. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70081-2. PMID 10365924.

- Morrow, David J. (March 19, 1999). "New Profits in Old Bottles; Companies Find Bonus in Drugs That Cure Several Ills". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "Patient Information About Proscar" (PDF). Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

- Gooren L (2005). "Hormone treatment of the adult transsexual patient". Hormone Research. 64 Suppl 2: 31–6. doi:10.1159/000087751. PMID 16286768.

- Knezevich EL, Viereck LK, Drincic AT (2012). "Medical management of adult transsexual persons". Pharmacotherapy. 32 (1): 54–66. doi:10.1002/PHAR.1006. PMID 22392828.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Altomare G, Capella GL (2002). "Depression circumstantially related to the administration of finasteride for androgenetic alopecia". The Journal of Dermatology. 29 (10): 665–9. PMID 12433001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hepp U, Kraemer B, Schnyder U, Miller N, Delsignore A (2005). "Psychiatric comorbidity in gender identity disorder". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 58 (3): 259–61. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.08.010. PMID 15865950.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Drugs.com | Propecia Side Effects

- 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs): Label Change - Increased Risk of Prostate Cancer | U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Walsh, PC (2010 Apr 1). "Chemoprevention of prostate cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (13): 1237–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1001045. PMID 20357287.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Can Prostate Cancer Be Prevented?" American Cancer Society, May 25, 2005.

- Gina Kolata (June 15, 2008). "New Take on a Prostate Drug, and a New Debate". NY Times. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- Redman, M. W.; Tangen, C. M.; Goodman, P. J.; Lucia, M. S.; Coltman, C. A.; Thompson, I. M. (2008). "Finasteride Does Not Increase the Risk of High-Grade Prostate Cancer: A Bias-Adjusted Modeling Approach". Cancer Prevention Research. 1 (3): 174–81. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0092. PMC 2844801. PMID 19138953.

- Traish AM, Hassani J, Guay AT, Zitzmann M, Hansen ML (2011). "Adverse side effects of 5α-reductase inhibitors therapy: persistent diminished libido and erectile dysfunction and depression in a subset of patients". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (3): 872–84. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02157.x. PMID 21176115.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Package Leaflet Information for the User, Swedish package insert for Propecia 1mg.

- MHRA PUBLIC ASSESSMENT REPORT | The risk of male breast cancer with finasteride

- ^ PROPECIA® (finasteride) | Merck & Co., Inc.

- <http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm299754.htm?utm_source=fdaSearch&utm_medium=website&utm_term=finasteride&utm_content=2>

- <http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2011/020180s039ltr.pdf>

- <http://www.businessweek.com/ap/2012-04/D9U3HR3G0.htm>

- ^ Römer B, Gass P (2010). "Finasteride-induced depression: new insights into possible pathomechanisms". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 9 (4): 331–2. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00533.x. PMID 21122055.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Finn DA, Beadles-Bohling AS, Beckley EH; et al. (2006). "A new look at the 5alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (1): 53–76. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00053.x. PMID 16834758.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rahimi-Ardabili B, Pourandarjani R, Habibollahi P, Mualeki A (2006). "Finasteride induced depression: a prospective study". BMC Clinical Pharmacology. 6: 7. doi:10.1186/1472-6904-6-7. PMC 1622749. PMID 17026771.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Allen, Jane E (3 May 2012). "Pursuit of Better Hairline Costs Some Men Their Sex Lives" (HTML). ABC News. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 2012/05/10.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "MHRA drug safety advice: Finasteride and potential risk of male breast cancer". 4 December 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- "FDA guidance on blood donors and medications" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original (pdf) on October 31, 2005. Retrieved 01-02-2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Sandomir, Richard (2006-01-19). "Skin Deep; Fighting Baldness, and Now an Olympic Ban". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- World Anti-Doping Agency Q&A: Status of Finasteride

- "Theodore's hair tonic causes positive test". TSN. 2006-02-10. Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- Aggarwal S, Thareja S, Verma A, Bhardwaj TR, Kumar M (2010). "An overview on 5alpha-reductase inhibitors". Steroids. 75 (2): 109–53. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2009.10.005. PMID 19879888.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "PROPECIA® (finasteride) Tablets, 1 mg [US/FDA label]" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-05/22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Bartsch G, Rittmaster RS, Klocker H (2000). "Dihydrotestosterone and the concept of 5alpha-reductase inhibition in human benign prostatic hyperplasia". European Urology. 37 (4): 367–80. PMID 10765065.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Drury JE, Di Costanzo L, Penning TM, Christianson DW (2009). "Inhibition of human steroid 5beta-reductase (AKR1D1) by finasteride and structure of the enzyme-inhibitor complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (30): 19786–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.C109.016931. PMC 2740403. PMID 19515843.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Robaire, B; Henderson, N (2006). "Actions of 5α-reductase inhibitors on the epididymis". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 250 (1–2): 190–5. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.044. PMID 16476520.

- Gunn BG, Brown AR, Lambert JJ, Belelli D (2011). "Neurosteroids and GABA(A) Receptor Interactions: A Focus on Stress". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 5: 131. doi:10.3389/fnins.2011.00131. PMC 3230140. PMID 22164129.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Vermeulen A, Giagulli VA, De Schepper P, Buntinx A, Stoner E (1989). "Hormonal effects of an orally active 4-azasteroid inhibitor of 5 alpha-reductase in humans". The Prostate. 14 (1): 45–53. PMID 2538808.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kokate TG, Banks MK, Magee T, Yamaguchi S, Rogawski MA (1999). "Finasteride, a 5alpha-reductase inhibitor, blocks the anticonvulsant activity of progesterone in mice". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (2): 679–84. PMID 9918575.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dusková M, Hill M, Hanus M, Matousková M, Stárka L (2009). "Finasteride treatment and neuroactive steroid formation". Prague Medical Report. 110 (3): 222–30. PMID 19655698.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Primary Patent Expirations for Selected High Revenue Drugs

- fda.gov | Patent Expiration for Propecia

- "Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Application Number NDA 20-788" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ "Letter to Dr. Sherman Frankel, University of Pennsylvania" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Rasmusson, Gary H.; Reynolds, Glenn F.; Steinberg, Nathan G.; Walton, Edward; Patel, Gool F.; Liang, Tehming; Cascieri, Margaret A.; Cheung, Anne H.; Brooks, Jerry R. (1986). "Azasteroids: structure-activity relationships for inhibition of 5.alpha.-reductase and of androgen receptor binding". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 29 (11): 2298–315. doi:10.1021/jm00161a028. PMID 3783591.

- Bhattacharya, Apurba.; Dimichele, Lisa M.; Dolling, Ulf H.; Douglas, Alan W.; Grabowski, Edward J. J. (1988). "Silylation-mediated oxidation of 4-aza-3-ketosteroids with DDQ proceeds via DDQ-substrate adducts". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110: 3318. doi:10.1021/ja00218a062.

- 5-Alpha-Reductase Deficiency | WebMD

- Dutasteride | Clinical Trials | International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery

- Freudenheim, Milt (February 16, 1992). "Keeping the Pipeline Filled at Merck". The New York Times.

External links

| Merck & Co., Inc. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate directors | |||

| Subsidiaries | |||

| Products |

| ||

| Facilities | |||

| Publications | |||

| Drugs used in benign prostatic hyperplasia (G04C) | |

|---|---|

| 5α-Reductase inhibitors | |

| Alpha-1 blockers | |

| Steroidal antiandrogens | |

| Herbal products | |

| Others | |