This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Generalrelative (talk | contribs) at 16:38, 28 June 2024 (Undid revision 1231495724 by Biohistorian15 (talk) I appreciate the vast majority of these recent changes, but this one looks like a substantive POV shift. Burying the "Discrimination" box would at least require a spot-check on Talk.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:38, 28 June 2024 by Generalrelative (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 1231495724 by Biohistorian15 (talk) I appreciate the vast majority of these recent changes, but this one looks like a substantive POV shift. Burying the "Discrimination" box would at least require a spot-check on Talk.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Effort to improve purported human genetic quality For the album, see Eugenics (album).

Eugenics (/juːˈdʒɛnɪks/ yoo-JEN-iks; from Ancient Greek εύ̃ (eû) 'good, well' and -γενής (genḗs) 'born, come into being, growing/grown') is a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior. Since the early 2020s, the term has seen a revival in bioethical discussions on the usage of new technologies such as CRISPR and genetic screening, with ongoing debate around whether these technologies should be considered eugenics or not.

The principles of eugenics have been in practice since ancient Greece. Plato suggested applying the principles of selective breeding to humans around 400 BCE. Nobility is also historically based on pedigree. Early advocates of eugenics in the 19th century regarded it as a way of improving groups of people. In contemporary usage, the term eugenics is closely associated with scientific racism. Modern bioethicists who advocate new eugenics characterize it as a matter of individual or parental choice in enhancing traits, rather than group-based policies.

The contemporary history of eugenics began in the late 19th century, when a popular eugenics movement emerged in the United Kingdom, and then spread to many countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, and most European countries (e.g. Sweden and Germany). In this period, people from across the political spectrum espoused eugenic ideas. Consequently, many countries adopted eugenic policies, intended to improve the quality of their populations' genetic stock. Such programs included both positive measures, such as encouraging individuals deemed particularly "fit" to reproduce, and negative measures, such as marriage prohibitions and forced sterilization of people deemed unfit for reproduction. Those deemed "unfit to reproduce" often included people with mental or physical disabilities, people who scored in the low ranges on different IQ tests, criminals and "sexual and social deviants", and members of disfavored minority groups.

History

Main article: History of eugenicsAncient and medieval origins

According to Plutarch, in Sparta every proper citizen's child was inspected by the council of elders, the Gerousia, which determined whether or not the child was fit to live. If the child was deemed incapable of living a Spartan life, the child was usually killed in a chasm near the Taygetus mountain known as the Apothetae. Further trials intended to discern a child's fitness included bathing them in wine and exposing them to the elements to fend for themselves, with the intention of ensuring that only those considered strongest survived and procreated.

The lack of sources by contemporary Greeks mentioning Spartan eugenics and the lack of archeological evidence has brought ideas about Spartan eugenics into question. While infanticide was practiced by Greeks, no contemporary sources support Plutarch's claims of mass infanticide motivated by eugenics. In 2007 the suggestion that infants were dumped near Mount Taygete was called into question due to a lack of physical evidence. Anthropologist Theodoros Pitsios' research found only bodies from adolescence up to the age of approximately 35.

Plato's political philosophy included the belief that human reproduction should be cautiously monitored and controlled by the state. He advocated that selective breeding should be applied to both humans and animals. Plato recognized that this form of government control would not be readily accepted, and proposed the truth be concealed from the public via a fixed lottery. Mates, in Plato's Republic, would be chosen by a "marriage number" in which the quality of the individual would be quantitatively analyzed, and persons of high numbers would be allowed to procreate with other persons of high numbers. This would then lead to predictable results and the improvement of the human race. Plato acknowledged the failure of the "marriage number" since "gold soul" persons could still produce "bronze soul" children. Plato's ideas may have been one of the earliest attempts to mathematically analyze genetic inheritance, prefiguring some of what would much later become known as Mendelian genetics.

The geographer Strabo (c. 64 BCE – c. 24 CE) stated that the Samnites would take ten virgin women and ten young men who were considered to be the best representation of their sex and mate them. Any selected male committing a dishonorable act would be separated from his partner.

In Ancient Rome, Seneca the Younger discussed selective infanticide, saying "We put down mad dogs; we kill the wild, untamed ox; we use the knife on sick sheep to stop their infecting the flock; we destroy abnormal offspring at birth; children, too, if they are born weak or deformed, we drown. Yet this is not the work of anger, but of reason – to separate the sound from the worthless."Academic origins

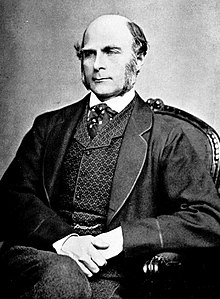

The term eugenics and its modern field of study were first formulated by Francis Galton in 1883, directly drawing on the recent work delineating natural selection by his half-cousin Charles Darwin. He published his observations and conclusions chiefly in his influential book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. Galton himself defined it as "the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations". The first to systematically apply Darwinism theory to human relations, Galton believed that various desirable human qualities were also hereditary ones, although Darwin strongly disagreed with this elaboration of his theory. And it should also be noted that many of the early geneticists were not themselves Darwinians.

Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities and received funding from various sources. Organizations were formed to win public support for and to sway opinion towards responsible eugenic values in parenthood, including the British Eugenics Education Society of 1907 and the American Eugenics Society of 1921. Both sought support from leading clergymen and modified their message to meet religious ideals. In 1909, the Anglican clergymen William Inge and James Peile both wrote for the Eugenics Education Society. Inge was an invited speaker at the 1921 International Eugenics Conference, which was also endorsed by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York Patrick Joseph Hayes.

Three International Eugenics Conferences presented a global venue for eugenicists, with meetings in 1912 in London, and in 1921 and 1932 in New York City. Eugenic policies in the United States were first implemented by state-level legislators in the early 1900s. Eugenic policies also took root in France, Germany, and Great Britain. Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, the eugenic policy of sterilizing certain mental patients was implemented in other countries including Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Japan and Sweden. Frederick Osborn's 1937 journal article "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy" framed eugenics as a social philosophy—a philosophy with implications for social order. That definition is not universally accepted. Osborn advocated for higher rates of sexual reproduction among people with desired traits ("positive eugenics") or reduced rates of sexual reproduction or sterilization of people with less-desired or undesired traits ("negative eugenics").

In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations. Its scientific aspects were carried on through research bodies such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, the Cold Spring Harbor Carnegie Institution for Experimental Evolution, and the Eugenics Record Office. Politically, the movement advocated measures such as sterilization laws. In its moral dimension, eugenics rejected the doctrine that all human beings are born equal and redefined moral worth purely in terms of genetic fitness. Its racist elements included pursuit of a pure "Nordic race" or "Aryan" genetic pool and the eventual elimination of "unfit" races. Many leading British politicians subscribed to the theories of eugenics. Winston Churchill supported the British Eugenics Society and was an honorary vice president for the organization. Churchill believed that eugenics could solve "race deterioration" and reduce crime and poverty.

Historically, the idea of eugenics has been used to argue for a broad array of practices ranging from prenatal care for mothers deemed genetically desirable to the forced sterilization and murder of those deemed unfit. To population geneticists, the term has included the avoidance of inbreeding without altering allele frequencies; for example, J. B. S. Haldane wrote that "the motor bus, by breaking up inbred village communities, was a powerful eugenic agent." Debate as to what exactly counts as eugenics continues today.

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with factors of perceived intelligence that often correlated strongly with social class. These included Karl Pearson and Walter Weldon, who worked on this at the University College London. In his lecture "Darwinism, Medical Progress and Eugenics", Pearson claimed that everything concerning eugenics fell into the field of medicine.

As a social movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century, when it was practiced around the world and promoted by governments, institutions, and influential individuals (such as the playwright G. B. Shaw). Many countries enacted various eugenics policies, including: genetic screenings, birth control, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation and sequestering the mentally ill), compulsory sterilization, forced abortions or forced pregnancies, ultimately culminating in genocide. By 2014, gene selection (rather than "people selection") was made possible through advances in genome editing, leading to what is sometimes called new eugenics, also known as "neo-eugenics", "consumer eugenics", or "liberal eugenics"; which focuses on individual freedom and allegedly pull away from racism, sexism, heterosexism or a focus on intelligence.

Early opposition

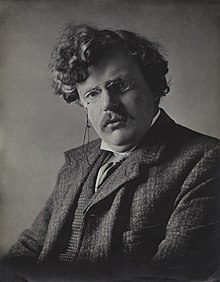

Early critics of the philosophy of eugenics included the American sociologist Lester Frank Ward, the English writer G. K. Chesterton, the German-American anthropologist Franz Boas, who argued that advocates of eugenics greatly over-estimate the influence of biology, and Scottish tuberculosis pioneer and author Halliday Sutherland. Ward's 1913 article "Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics", Chesterton's 1917 book Eugenics and Other Evils, and Boas' 1916 article "Eugenics" (published in The Scientific Monthly) were all harshly critical of the rapidly growing movement. Sutherland identified eugenicists as a major obstacle to the eradication and cure of tuberculosis in his 1917 address "Consumption: Its Cause and Cure", and criticism of eugenicists and Neo-Malthusians in his 1921 book Birth Control led to a writ for libel from the eugenicist Marie Stopes. Several biologists were also antagonistic to the eugenics movement, including Lancelot Hogben. Other biologists such as J. B. S. Haldane and R. A. Fisher expressed skepticism in the belief that sterilization of "defectives" would lead to the disappearance of undesirable genetic traits.

Among institutions, the Catholic Church was an opponent of state-enforced sterilizations, but accepted isolating people with hereditary diseases so as not to let them reproduce. Attempts by the Eugenics Education Society to persuade the British government to legalize voluntary sterilization were opposed by Catholics and by the Labour Party. The American Eugenics Society initially gained some Catholic supporters, but Catholic support declined following the 1930 papal encyclical Casti connubii. In this, Pope Pius XI explicitly condemned sterilization laws: "Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason."

In fact, more generally, "uch of the opposition to eugenics during that era, at least in Europe, came from the right." The eugenicists' political successes in Germany and Scandinavia were not at all matched in such countries as Poland and Czechoslovakia, even though measures had been proposed there, largely because of the Catholic church's moderating influence.

Modalities of the old eugenics

Eugenic policies have been conceptually divided into two categories. Positive eugenics is aimed at encouraging reproduction among the genetically advantaged; for example, the reproduction of the intelligent, the healthy, and the successful. Possible approaches include financial and political stimuli, targeted demographic analyses, in vitro fertilization, egg transplants, and cloning. Negative eugenics aimed to eliminate, through sterilization or segregation, those deemed physically, mentally, or morally "undesirable". This includes abortions, sterilization, and other methods of family planning. Both positive and negative eugenics can be coercive; in Nazi Germany, for example, abortion was illegal for women deemed by the state to be fit.

Compulsory sterilization

This section is an excerpt from Compulsory sterilization.Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, refers to any government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done by surgical or chemical means.

Purported justifications for compulsory sterilization have included population control, eugenics, limiting the spread of HIV, and ethnic genocide.

Several countries implemented sterilization programs in the early 20th century. Although such programs have been made illegal in much of the world, instances of forced or coerced sterilizations still persist.Eugenic feminism

This section is an excerpt from Eugenic feminism.

Eugenic feminism was a current of the women's suffrage movement which overlapped with eugenics. Originally coined by the Lebanese-British physician and vocal eugenicist Caleb Saleeby, the term has since been applied to summarize views held by prominent feminists of Great Britain and the United States. Some early suffragettes in Canada, especially a group known as The Famous Five, also pushed for various eugenic policies.

Eugenic feminists argued that if women were provided with more rights and equality, the deteriorating characteristics of a given race could be averted.Eugenics in the United States

Main article: Eugenics in the United StatesAnti-miscegenation laws in the United States made it a crime for individuals to wed someone categorized as belonging to a different race. These laws were part of a broader policy of racial segregation in the United States to minimize contact between people of different ethnicities. Race laws and practices in the United States were explicitly used as models by the Nazi regime when it developed the Nuremberg Laws, stripping Jewish citizens of their citizenship.

Indeed, the eugenics movement became widely associated with Nazi Germany and the Holocaust when the defense of many of the defendants at the Nuremberg trials of 1945 to 1946 attempted to justify their human-rights abuses by claiming there was little difference between the Nazi eugenics programs and the US eugenics programs.

Nazism and the decline of eugenics

Main article: Nazi eugenics See also: Racial hygiene, Life unworthy of life, and Scientific racism

The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler had praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in Mein Kampf in 1925 and emulated eugenic legislation for the sterilization of "defectives" that had been pioneered in the United States once he took power. Some common early 20th century eugenics methods involved identifying and classifying individuals and their families, including the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women, homosexuals, and racial groups (such as the Roma and Jews in Nazi Germany) as "degenerate" or "unfit", and therefore led to segregation, institutionalization, sterilization, and even mass murder. The Nazi policy of identifying German citizens deemed mentally or physically unfit and then systematically killing them with poison gas, referred to as the Aktion T4 campaign, is understood by historians to have paved the way for the Holocaust.

By the end of World War II, many eugenics laws were abandoned, having become associated with Nazi Germany. H. G. Wells, who had called for "the sterilization of failures" in 1904, stated in his 1940 book The Rights of Man: Or What Are We Fighting For? that among the human rights, which he believed should be available to all people, was "a prohibition on mutilation, sterilization, torture, and any bodily punishment". After World War II, the practice of "imposing measures intended to prevent births within group" fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also proclaims "the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at selection of persons".

In spite of the decline in discriminatory eugenics laws, some government mandated sterilizations continued into the 21st century. During the ten years President Alberto Fujimori led Peru from 1990 to 2000, 2,000 persons were allegedly involuntarily sterilized. China maintained its one-child policy until 2015 as well as a suite of other eugenics-based legislation to reduce population size and manage fertility rates of different populations.

Modern eugenics

Main article: New eugenicsDevelopments in genetic, genomic, and reproductive technologies at the beginning of the 21st century have raised numerous questions regarding the ethical status of eugenics, effectively creating a resurgence of interest in the subject. Some, such as UC Berkeley sociologist Troy Duster, have argued that modern genetics is a back door to eugenics. This view was shared by then-White House Assistant Director for Forensic Sciences, Tania Simoncelli, who stated in a 2003 publication by the Population and Development Program at Hampshire College that advances in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) are moving society to a "new era of eugenics", and that, unlike the Nazi eugenics, modern eugenics is consumer driven and market based, "where children are increasingly regarded as made-to-order consumer products".

In October 2015, the United Nations' International Bioethics Committee wrote that the ethical problems of human genetic engineering should not be confused with the ethical problems of the 20th century eugenics movements. However, it is still problematic because it challenges the idea of human equality and opens up new forms of discrimination and stigmatization for those who do not want, or cannot afford, the technology.

The American National Human Genome Research Institute says that eugenics is "inaccurate", "scientifically erroneous and immoral".

Transhumanism is often associated with eugenics, although most transhumanists holding similar views nonetheless distance themselves from the term "eugenics" (preferring "germinal choice" or "reprogenetics") to avoid having their position confused with the discredited theories and practices of early-20th-century eugenic movements.

Prenatal screening has been called by some a contemporary form of eugenics because it may lead to abortions of fetuses with undesirable traits.

In Singapore

Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of Singapore, promoted eugenics as late as 1983. A proponent of nature over nurture, he stated that "intelligence is 80% nature and 20% nurture", and attributed the successes of his children to genetics. In his speeches, Lee urged highly educated women to have more children, claiming that "social delinquents" would dominate unless their fertility rate increased. In 1984, Singapore began providing financial incentives to highly educated women to encourage them to have more children. In 1985, incentives were significantly reduced after public uproar.

Controversy over scientific and moral legitimacy

One criticism of eugenics policies is that, regardless of whether negative or positive policies are used, they are susceptible to abuse because the genetic selection criteria are determined by whichever group has political power at the time. Furthermore, many criticize negative eugenics in particular as a violation of certain human rights claims, chiefly the right to reproduce. On the other hand, liberal proponents of human enhancement (and therein usually first and foremost positive eugenics), have long since used terminology much like this as well. A notable such appeal to much the same effect is that of philosopher and political libertarian John A. Robertson’s “procreative liberty.” More generally yet, the exact foundations of human rights claims are themselves commonly contested in scholarly contexts, with various personages likely to reject them outright and an especially broad battery of rebuttals having accumulated against their use in favor of bioethics regulation in particular.

Another concern is that reduced genetic diversity could eventually result in inbreeding depression, increased spread of infectious disease, and decreased resilience to changes in the environment.

Throughout its recent history, eugenics has remained a highly controversial matter.

Arguments for scientific validity

Most generally, in a 2006 newspaper article, prominent evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, lauded by some as "the skeptic's chaplain", stated of the matter:

The spectre of Hitler has led some scientists to stray from "ought" to "is" and deny that breeding for human qualities is even possible. But if you can breed cattle for milk yield, horses for running speed, and dogs for herding skill, why on Earth should it be impossible to breed humans for mathematical, musical or athletic ability? Objections such as "these are not one-dimensional abilities" apply equally to cows, horses and dogs and never stopped anybody in practice.

I wonder whether, some 60 years after Hitler's death, we might at least venture to ask what the moral difference is between breeding for musical ability and forcing a child to take music lessons. Or why it is acceptable to train fast runners and high jumpers but not to breed them. I can think of some answers, and they are good ones, which would probably end up persuading me. But hasn't the time come when we should stop being frightened even to put the question?

The heterozygote test is used for the early detection of recessive hereditary diseases, allowing for couples to determine if they are at risk of passing genetic defects to a future child. The goal of the test is to estimate the likelihood of passing the hereditary disease to future descendants.

There are examples of eugenic acts that managed to lower the prevalence of recessive diseases, although not influencing the prevalence of heterozygote carriers of those diseases. The elevated prevalence of certain genetically transmitted diseases among the Ashkenazi Jewish population (Tay–Sachs, cystic fibrosis, Canavan's disease, and Gaucher's disease), has been decreased in current populations by the application of genetic screening.

Objections to scientific validity

The first major challenge to conventional eugenics based on genetic inheritance was made in 1915 by Thomas Hunt Morgan. He demonstrated the event of genetic mutation occurring outside of inheritance involving the discovery of the hatching of a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) with white eyes from a family with red eyes, demonstrating that major genetic changes occurred outside of inheritance. Additionally, Morgan criticized the view that certain traits, such as intelligence and criminality, were hereditary because these traits were subjective. Despite Morgan's public rejection of eugenics, much of his genetic research was adopted by proponents of eugenics.

Pleiotropy occurs when one gene influences multiple, seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits, an example being phenylketonuria, which is a human disease that affects multiple systems but is caused by one gene defect. Andrzej Pękalski, from the University of Wroclaw, argues that eugenics can cause harmful loss of genetic diversity if a eugenics program selects a pleiotropic gene that could possibly be associated with a positive trait. Pękalski uses the example of a coercive government eugenics program that prohibits people with myopia from breeding but has the unintended consequence of also selecting against high intelligence since the two go together. Further, a culturally-accepted "improvement" of the gene pool may result in extinction, due to increased vulnerability to disease, reduced ability to adapt to environmental change, and other factors that may not be anticipated in advance. This has been evidenced in numerous instances, in inbred isolated island populations. A long-term, species-wide eugenics plan might lead to such a scenario because the elimination of traits deemed undesirable would reduce genetic diversity by definition.

While the science of genetics has increasingly provided means by which certain characteristics and conditions can be identified and understood, given the complexity of human genetics, culture, and psychology, at this point there is no agreed objective means of determining which traits might be ultimately desirable or undesirable. Some conditions such as sickle-cell disease and cystic fibrosis respectively confer immunity to malaria and resistance to cholera when a single copy of the recessive allele is contained within the genotype of the individual, so eliminating these genes is undesirable in places where such diseases are common.

Amanda Caleb, Professor of Medical Humanities at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, says "Eugenic laws and policies are now understood as part of a specious devotion to a pseudoscience that actively dehumanizes to support political agendas and not true science or medicine."

Edwin Black, journalist, historian, and author of War Against the Weak, argues that eugenics is often deemed a pseudoscience because what is defined as a genetic improvement of a desired trait is a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined through objective scientific inquiry. Indeed, the most disputed aspect of eugenics has been the definition of "improvement" of the human gene pool, such as what is a beneficial characteristic and what is a defect. Historically, this aspect of eugenics is often considered to be tainted with scientific racism and pseudoscience.

Regarding the lasting controversy above, himself citing recent scholarship, historian of science Aaron Gillette notes that:

thers take a more nuanced view. They recognize that there was a wide variety of eugenic theories, some of which were much less race- or class-based than others. Eugenicists might also give greater or lesser acknowledgment to the role that environment played in shaping human behavior. In some cases, eugenics was almost imperceptibly intertwined with health care, child care, birth control, and sex education issues. In this sense, eugenics has been called, "a 'modern' way of talking about social problems in biologizing terms".'

Indeed, granting that the historical phenomenon of eugenics was that of a pseudoscience, Gilette further notes that this derived chiefly from its being "an epiphenomenon of a number of sciences, which all intersected at the claim that it was possible to consciously guide human evolution."

Ethical controversies

Societal and political consequences of eugenics call for a place in the discussion on the ethics behind the eugenics movement. Many of the ethical concerns regarding eugenics arise from its controversial past, prompting a discussion on what place, if any, it should have in the future. Advances in science have changed eugenics. In the past, eugenics had more to do with sterilization and enforced reproduction laws. Now, in the age of a progressively mapped genome, embryos can be tested for susceptibility to disease, sex, and genetic defects, and alternative methods of reproduction such as in vitro fertilization are becoming more common. Therefore, eugenics is no longer ex post facto regulation of the living but instead preemptive action on the unborn.

With this change, however, there are ethical concerns which some groups feel warrant more attention before this practice is commonly rolled out. Sterilized individuals, for example, could volunteer for the procedure, albeit under incentive or duress, or at least voice their opinion. The unborn fetus on which these new eugenic procedures are performed cannot speak out, as the fetus lacks the voice to consent or to express their opinion. Philosophers disagree about the proper framework for reasoning about such actions, which change the very identity and existence of future persons.

Opposition

Edwin Black has described potential "eugenics wars" as the worst-case outcome of eugenics. In his view, this scenario would mean the return of coercive state-sponsored genetic discrimination and human rights violations such as the compulsory sterilization of persons with genetic defects, the killing of the institutionalized and, specifically, the segregation and genocide of races which are considered inferior. Law professors George Annas and Lori Andrews have argued that the use of these technologies could lead to such human-posthuman caste warfare.

Environmental ethicist Bill McKibben argued against germinal choice technology and other advanced biotechnological strategies for human enhancement. He writes that it would be morally wrong for humans to tamper with fundamental aspects of themselves (or their children) in an attempt to overcome universal human limitations, such as vulnerability to aging, maximum life span and biological constraints on physical and cognitive ability. Attempts to "improve" themselves through such manipulation would remove limitations that provide a necessary context for the experience of meaningful human choice. He claims that human lives would no longer seem meaningful in a world where such limitations could be overcome with technology. Even the goal of using germinal choice technology for clearly therapeutic purposes should be relinquished, he argues, since it would inevitably produce temptations to tamper with such things as cognitive capacities. He argues that it is possible for societies to benefit from renouncing particular technologies, using Ming China, Tokugawa Japan and the contemporary Amish as examples.

Endorsement

Some, for example Nathaniel C. Comfort from Johns Hopkins University, claim that the change from state-led reproductive-genetic decision-making to individual choice has moderated the worst abuses of eugenics by transferring the decision-making process from the state to patients and their families. Comfort suggests that "the eugenic impulse drives us to eliminate disease, live longer and healthier, with greater intelligence, and a better adjustment to the conditions of society; and the health benefits, the intellectual thrill and the profits of genetic bio-medicine are too great for us to do otherwise." Others, such as bioethicist Stephen Wilkinson of Keele University and Honorary Research Fellow Eve Garrard at the University of Manchester, claim that some aspects of modern genetics can be classified as eugenics, but that this classification does not inherently make modern genetics immoral.

In their book published in 2000, From Chance to Choice: Genetics and Justice, bioethicists Allen Buchanan, Dan Brock, Norman Daniels and Daniel Wikler argued that liberal societies have an obligation to encourage as wide an adoption of eugenic enhancement technologies as possible (so long as such policies do not infringe on individuals' reproductive rights or exert undue pressures on prospective parents to use these technologies) in order to maximize public health and minimize the inequalities that may result from both natural genetic endowments and unequal access to genetic enhancements.

In his book A Theory of Justice (1971), American philosopher John Rawls argued that "ver time a society is to take steps to preserve the general level of natural abilities and to prevent the diffusion of serious defects". The original position, a hypothetical situation developed by Rawls, has been used as an argument for negative eugenics.

In science fiction

See also: Speculative evolution, Evolution in fiction, and Genetics in fictionThe novel Brave New World by the English author Aldous Huxley (1931), is a dystopian social science fiction novel which is set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy.

Various works by the author Robert A. Heinlein mention the Howard Foundation, a group which attempts to improve human longevity through selective breeding.

Among Frank Herbert's other works, the Dune series, starting with the eponymous 1965 novel, describes selective breeding by a powerful sisterhood, the Bene Gesserit, to produce a supernormal male being, the Kwisatz Haderach.

The Star Trek franchise features a race of genetically engineered humans which is known as "Augments", the most notable of them is Khan Noonien Singh. These "supermen" were the cause of the Eugenics Wars, a dark period in Earth's fictional history, before they were deposed and exiled. They appear in many of the franchise's story arcs, most frequently, they appear as villains.

The film Gattaca (1997) provides a fictional example of a dystopian society that uses eugenics to decide what people are capable of and what their place in the world is. The title alluding to the letters G, A, T and C, the four nucleobases of DNA, and depicts the possible consequences of genetic discrimination in the present societal framework. Nonetheless, against mere uniformity being the movies key theme, it may be highlighted that it also includes an esteemed concert pianist with 12 fingers. Even though Gattaca was not a box office success, it was critically acclaimed and it is said to have crystallized the debate over human genetic engineering in the public consciousness. It has been cited by many bioethicists and laypeople in support of their hesitancy about, or opposition to, eugenics and the genetic determinist ideology that may frame it. As to its accuracy, its production company, Sony Pictures, consulted with a gene therapy researcher and prominent critic of eugenics known to have stated that "e should not step over the line that delineates treatment from enhancement", William French Anderson, to ensure that the portrayal of science was realistic. Disputing their sucess in this mission, Philim Yam of Scientific American called the film "science bashing" and Nature's Kevin Davies called it a "surprisingly pedestrian affair", while molecular biologist Lee Silver described its extreme determinism as "a straw man". In an even more pointed critique, in his 2018 book Blueprint, the behavioral geneticist Robert Plomin writes that while Gattaca warned of the dangers of genetic information being used by a totalitarian state, genetic testing could also favor better meritocracy in democratic societies which already administer a variety of standardized tests to select people for education and employment. Plomin suggests that polygenic scores might supplement testing in a manner that is free of biases. Along similar lines, in the 2004 book Citizen Cyborg democratic transhumanist James Hughes had already argued against what he considers to be "professional fear-mongers", stating of the movie's premises:

- Astronaut training programs are entirely justified in attempting to screen out people with heart problems for safety reasons;

- In the United States, people are already being screened by insurance companies on the basis of their propensities to disease, for actuarial purposes;

- Rather than banning genetic testing or genetic enhancement, society should simply develop genetic information privacy laws, such as the U.S. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, that allow justified forms of genetic testing and data aggregation, but forbid those that are judged to result in genetic discrimination.

See also

- Bioconservatism – Cautious stance towards modifying human nature

- Culling – Process of segregating organisms in biology

- Directed evolution (transhumanism) – Concept in transhumanist discourses

- Dor Yeshorim – Jewish genetic screening organization

- Dysgenics – Decrease in genetic traits deemed desirable

- Eugenic feminism – Areas of the women's suffrage movement which overlapped with eugenics

- Eugenics in Mexico

- Euthenics – Study of improving living conditions to increase well-being

- Fertility and income

- Fertility and intelligence – Relationship that has been the focus of demographic studies

- Genetic engineering – Manipulation of an organism's genome

- Genetic enhancement – Technologies to genetically improve human bodiesPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Heritability of IQ – Percent of variation in IQ scores in a given population associated with genetic variation

- Human enhancement – Natural, artificial, or technological alteration of the human body

- In vitro embryo selection – Assisted reproductive technology procedure (Preimplantation genetic diagnosis – Genetic profiling of embryos prior to implantation)

- New eugenics – Liberal use of reprogenetics in human enhancement

- Mendelian traits in humans

- Moral enhancement – Use of biotechnology to improve one's character

- Procreative beneficence – Australian philosopher and bioethicistPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets Julian Savulescu coined this concept

- Prevention of rare diseases – Disease affecting a small percentage of the population

- Social Darwinism – Group of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices

- Wrongful life – Civil law action which alleges that a defendant has wrongfully caused a child to be born

References

- Galton, Francis (2002) . Tredoux, Gavan (ed.). Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development (PDF). pp. 17, 30. Retrieved 21 July 2023 – via Online Galton Archives.

what is termed in Greek, eugenes namely, good in stock, hereditarily endowed with noble qualities. This, and the allied words, eugeneia, etc., are equally applicable to men, brutes, and plants. We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognisance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word eugenics would sufficiently express the idea; it is at least a neater word and a more generalized one than viriculture which I once ventured to use.... The investigation of human eugenics – that is, of the conditions under which men of a high type are produced – is at present extremely hampered by the want of full family histories, both medical and general, extending over three or four generations.

- "εὐγενής". Greek Word Study Tool. Medford, Massachusetts: Tufts University. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2017. Database includes entries from A Greek–English Lexicon and other English dictionaries of Ancient Greek.

- ^ Black 2003, p. 370.

- "Eugenics – African American Studies". Oxford Bibliographies. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

Racially targeted sterilization practices between the 1960s and the present have been perhaps the most common topic among scholars arguing for, and challenging, the ongoing power of eugenics in the United States. Indeed, unlike in the modern period, contemporary expressions of eugenics have met with widespread, thoroughgoing resistance

- Galton, Francis (1904). "Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims". The American Journal of Sociology. X (1): 82. Bibcode:1904Natur..70...82.. doi:10.1038/070082a0. Archived from the original on 1 March 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ Spektorowski, Alberto; Ireni-Saban, Liza (2013). Politics of Eugenics: Productionism, Population, and National Welfare. London: Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9780203740231. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

As an applied science, thus, the practice of eugenics referred to everything from prenatal care for mothers to forced sterilization and euthanasia. Galton divided the practice of eugenics into two types—positive and negative—both aimed at improving the human race through selective breeding.

- Veit, Walter; Anomaly, Jonathan; Agar, Nicholas; Singer, Peter; Fleischman, Diana; Minerva, Francesca (2021). "Can 'eugenics' be defended?" (PDF). Monash Bioethics Review. 39 (1): 60–67. doi:10.1007/s40592-021-00129-1. PMC 8321981. PMID 34033008.

- "Eugenics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2022.

- Hansen, Randall; King, Desmond (1 January 2001). "Eugenic Ideas, Political Interests and Policy Variance Immigration and Sterilization Policy in Britain and U.S". World Politics. 53 (2): 237–263. doi:10.1353/wp.2001.0003. JSTOR 25054146. PMID 18193564. S2CID 19634871.

- McGregor, Russell (2002). "'Breed out the colour' or the importance of being white". Australian Historical Studies. 33 (120): 286–302. doi:10.1080/10314610208596220. S2CID 143863018. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Hughes, Bill (26 September 2019). A Historical Sociology of Disability: Human Validity and Invalidity from Antiquity to Early Modernity. Routledge Advances in Disability Studies. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9780429615207. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

The Spartan Council of Elders or Gerousia decided whether a new-born child brought before them would live or die. Impairment, deformity, even puny appearance was enough to condemn a child to death.

- Making Patriots by Walter Berns, 2001, page 12, "and whose infants, if they chanced to be puny or ill-formed, were exposed in a chasm (the Apothetae) and left to die;"

- Plutarch. Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans.

- Allen G. Roper, Ancient Eugenics (Oxford: Cliveden Press, 1913)

- Sneed (2021). "Disability and Infanticide in Ancient Greece". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 90 (4): 747. doi:10.2972/hesperia.90.4.0747. S2CID 245045967.

- "Study finds no evidence of discarded Spartan babies". ABC News. 10 December 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- "Ancient Sparta – Research Program of Keadas Cavern" https://web.archive.org/web/20131002192630/http://www.anthropologie.ch/d/publikationen/archiv/2010/documents/03PITSIOSreprint.pdf

- Galton, David J. (1998). "Greek theories on eugenics." Journal of Medical Ethics, 24(4), 263–267. doi:10.1136/jme.24.4.263

- The Republic, 457c10-d3

- Brumbaugh, Robert S. (1954). "Plato's Genetic Theory", Journal of Heredity, 45(4):191–196, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a106472

- Geographica, Strabo, Book 5, page 467. "And they say that among the Samnitae there is a law which is indeed honourable and conducive to noble qualities; for they are not permitted to give their daughters in marriage to whom they wish, but every year ten virgins and ten young men, the noblest of each sex, are selected, and, of these, the first choice of the virgins is given to the first choice of the young men, and the second to the second, and so on to the end; but if the young man who wins the meed of honour changes and turns out bad, they disgrace him and take away from him the woman given him."

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus (1995). Seneca: Moral and Political Essays. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-5213-4818-8. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Galton, Francis (1883). Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development. London: Macmillan Publishers. p. 199.

- James D., Watson; Berry, Andrew (2009). DNA: The Secret of Life. Knopf. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Galton, Francis (1874). "On men of science, their nature and their nurture". Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain. 7: 227–236. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Ward, Lester Frank; Palmer Cape, Emily; Simons, Sarah Emma (1918). "Eugenics, Euthenics and Eudemics". Glimpses of the Cosmos. G.P. Putnam. pp. 382 ff. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- "Correspondence between Francis Galton and Charles Darwin". Galton.org. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- "The Correspondence of Charles Darwin". Darwin Correspondence Project. University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J (2003), Evolution: The History of an Idea (3rd ed.), University of California Press, pp. 308–310

- ^ Blom, Philipp (2008). The Vertigo Years: Change and Culture in the West, 1900–1914. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. pp. 335–336. ISBN 9780771016301.

- Cited in Black 2003, p. 18

- ^ Hansen, Randall (2005). "Eugenics". In Gibney, Matthew J.; Hansen, Randall (eds.). Eugenics: Immigration and Asylum from 1990 to Present. ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Allen, Garland E. (2004). "Was Nazi eugenics created in the US?". EMBO Reports. 5 (5): 451–452. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400158. PMC 1299061.

- ^ Baker, G. J. (2014). "Christianity and Eugenics: The Place of Religion in the British Eugenics Education Society and the American Eugenics Society, c. 1907–1940". Social History of Medicine. 27 (2): 281–302. doi:10.1093/shm/hku008. PMC 4001825. PMID 24778464.

- Barrett, Deborah; Kurzman, Charles (October 2004). "Globalizing Social Movement Theory: The Case of Eugenics" (PDF). Theory and Society. 33 (5): 487–527. doi:10.1023/b:ryso.0000045719.45687.aa. JSTOR 4144884. S2CID 143618054. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

Policy adoption: In the pre–World War I period, eugenic policies were enacted only in the United States, which was both the hotbed of international eugenics activism and unusually decentralized politically, so that sub-national state units could adopt such policies in the absence of central state approval.

- Hawkins, Mike (1997). Social Darwinism in European and American Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62, 292. ISBN 9780521574341.

- "The National Office of Eugenics in Belgium". Science. 57 (1463): 46. 12 January 1923. Bibcode:1923Sci....57R..46.. doi:10.1126/science.57.1463.46.

- dos Santos, Sales Augusto; Hallewell, Laurence (January 2002). "Historical Roots of the 'Whitening' of Brazil". Latin American Perspectives. 29 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1177/0094582X0202900104. JSTOR 3185072. S2CID 220914100.

- McLaren, Angus (1990). Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780771055447.

- Osborn, Frederick (June 1937). "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy". American Sociological Review. 2 (3): 389–397. doi:10.2307/2084871. JSTOR 2084871.

- Black 2003, p. 240.

- Black 2003, p. 286.

- Black 2003, p. 40.

- Black 2003, p. 45.

- Black 2003, Chapter 6: The United States of Sterilization.

- Black 2003, p. 237.

- Black 2003, Chapter 5: Legitimizing Raceology.

- Black 2003, Chapter 9: Mongrelization.

- Jones, S. (1995). The Language of Genes: Solving the Mysteries of Our Genetic Past, Present and Future (New York: Anchor).

- King, D. (1999). In the name of liberalism: illiberal social policy in Britain and the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Haldane, J. (1940). "Lysenko and Genetics". Science and Society. 4 (4). Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- A discussion of the shifting meanings of the term can be found in Paul, Diane (1995). Controlling Human Heredity: 1865 to the Present. Humanities Press. ISBN 9781573923439.

- Salgirli, S. G. (July 2011). "Eugenics for the doctors: Medicine and social control in 1930s Turkey". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 66 (3): 281–312. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrq040. PMID 20562206. S2CID 205167694.

- Ridley, Matt (1999). Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 290–291. ISBN 9780060894085.

- Reis, Alex; Hornblower, Breton; Robb, Brett; Tzertzinis, George (2014). "CRISPR/Cas9 and Targeted Genome Editing: A New Era in Molecular Biology". NEB Expressions (I). Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Goering, Sara (2014), "Eugenics", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2014 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, archived from the original on 7 November 2020, retrieved 4 May 2022

- Chesterton, G. K. (1922). Eugenics and Other Evils. Cassell and Company.

- Ferrante, Joan (2010). Sociology: A Global Perspective. Cengage Learning. pp. 259 ff. ISBN 9780840032041. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Turda, Marius (2010). "Race, Science and Eugenics in the Twentieth Century". In Bashford, Alison; Levine, Philippa (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9780199888290.

- "Consumption: Its Cause and Cure" – an address by Dr Halliday Sutherland on 4 September 1917, published by the Red Triangle Press.

- "Lancelot Hogben, who developed his critique of eugenics and distaste for racism in the period...he spent as Professor of Zoology at the University of Cape Town". Alison Bashford and Philippa Levine, The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2010 ISBN 0199706530 (p. 200)

- "Whatever their disagreement on the numbers, Haldane, Fisher, and most geneticists could support Jennings's warning: To encourage the expectation that the sterilization of defectives will solve the problem of hereditary defects, close up the asylums for feebleminded and insane, do away with prisons, is only to subject society to deception". Daniel J. Kevles (1985). In the Name of Eugenics. University of California Press. ISBN 0520057635 (p. 166).

- Congar, Yves M.-J. (1953). The Catholic Church and the Race Question (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

4. The State is not entitled to deprive an individual of his procreative power simply for material (eugenic) purposes. But it is entitled to isolate individuals who are sick and whose progeny would inevitably be seriously tainted.

- Bashford, Alison; Levine, Philippa (2010). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195373141. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2018 – via Google Books.

- Pope Pius XI. "Casti connubii". Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Buchanan, Allen; Brock, Dan W.; Daniels, Norman; Wikler, Daniel (2000). From Chance to Choice: Genetics and Justice. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521669771. OCLC 41211380.

- Roll-Hansen, Nils (1988). "The Progress of Eugenics: Growth of Knowledge and Change in Ideology." History of Science, xxvi, 295-331.

- ^ Glad, John (2008). Future Human Evolution: Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century. Hermitage Publishers. ISBN 9781557791542.

- Pine, Lisa (1997). Nazi Family Policy, 1933–1945. Berg. pp. 19 ff. ISBN 9781859739075. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Webster University, Forced Sterilization. Retrieved on 30 August 2014. "Women and Global Human Rights". Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- Rosario, Esther (13 September 2013). "Feminism". The Eugenics Archives. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Saleeby, Caleb Williams (1911). "First Principles". Woman and Womanhood A Search for Principles. New York: J. J. Little & Ives Co. MITCHELL KENNERLEY. p. 7.

The mark of the following pages is that they assume the principle of what we may call Eugenic Feminism

- Saleeby, Caleb. "Woman suffrage, eugenics, and eugenic feminism in Canada « Women Suffrage and Beyond". womensuffrage.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2018..

- Gibbons, Sheila Rae. "Women's suffrage". The Eugenics Archives. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

Dr. Caleb Saleeby, an obstetrician and active member of the British Eugenics Education Society, opposed his contemporaries – such as Sir Francis Galton – who took strong anti-feminist stances in their eugenic philosophies. Perceiving the feminist movement as potentially "ruinous to the race" if it continued to ignore the eugenics movement, he coined the term "eugenic feminism" in his 1911 text Woman and Womanhood: A Search for Principles

- "EugenicsArchive". eugenicsarchive.org.

- Whitman, James Q. (2003). Hitler's American model | The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Laws. Princeton University Press. p. 2 and following. ISBN 9780691172422. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020.

- Bashford, Alison; Levine, Philippa (3 August 2010). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. p. 327. ISBN 9780199706532. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

Eugenics was prominent at the Nuremberg trials ... much was made of the similarity between US and German eugenics by the defense, who argued that German eugenics differed little from that practiced in the United States ... .

- Black 2003, pp. 274–295.

- ^ Black 2003.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford University Press. pp. 179–191. ISBN 9780192804365.

- Burleigh, Michael (2000). "Psychiatry, German Society, and the Nazi "Euthanasia" Programme". In Bartov, Omer (ed.). Holocaust: Origins, Implementation, Aftermath. London: Routledge. pp. 43–57. ISBN 0415150361.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. pp. 256–258. ISBN 9781441761460.

- Black, Edwin (2003). War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race. Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 9781568582580.

- Turner, Jacky (2010). Animal Breeding, Welfare and Society. Routledge. p. 296. ISBN 9781844075898.

- Clapham, Andrew (2007). Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 9780199205523.

- Article 2 of the Convention defines genocide as any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such as:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

- "Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union". Article 3, Section 2. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Meilhan, Pierre & Brumfield, Ben (25 January 2014). "Peru will not prosecute former President over sterilization campaign". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Dikötter, F. (1998). Imperfect Conceptions: Medical Knowledge, Birth Defects, and Eugenics in China. Columbia University Press.

- Miller, Geoffrey (2013). "2013: What Should We Be Worried About? Chinese Eugenics". Edge. Edge Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- Dikötter, F. (1999). "'The legislation imposes decisions': Laws about eugenics in China". UNESCO Courier. 1.

- Epstein, Charles J. (1 November 2003). "Is modern genetics the new eugenics?". Genetics in Medicine. 5 (6): 469–475. doi:10.1097/01.GIM.0000093978.77435.17. PMID 14614400.

- Simoncelli, Tania (2003). "Pre-implantation Genetic Diagnosis and Selection: From disease prevention to customized conception" (PDF). Different Takes. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- "Report of the IBC on Updating Its Reflection on the Human Genome and Human Rights" (PDF). International Bioethics Committee. 2 October 2015. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

The goal of enhancing individuals and the human species by engineering the genes related to some characteristics and traits is not to be confused with the barbarous projects of eugenics that planned the simple elimination of human beings considered as 'imperfect' on an ideological basis. However, it impinges upon the principle of respect for human dignity in several ways. It weakens the idea that the differences among human beings, regardless of the measure of their endowment, are exactly what the recognition of their equality presupposes and therefore protects. It introduces the risk of new forms of discrimination and stigmatization for those who cannot afford such enhancement or simply do not want to resort to it. The arguments that have been produced in favour of the so-called liberal eugenics do not trump the indication to apply the limit of medical reasons also in this case.

- "Eugenics and Scientific Racism". Genome.gov. National Human Genome Research Institute. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- Silver, Lee M. (1998). Remaking Eden: Cloning and Beyond in a Brave New World. Harper Perennial. ISBN 9780380792436. OCLC 40094564.

- Thomas, Gareth M.; Rothman, Barbara Katz (April 2016). "Keeping the Backdoor to Eugenics Ajar?: Disability and the Future of Prenatal Screening". AMA Journal of Ethics. 18 (4): 406–415. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.4.stas1-1604. PMID 27099190.

We argue that prenatal screening (and specifically NIPT) for Down syndrome can be considered a form of contemporary eugenics, in that it effaces, devalues, and possibly prevents the births of people with the condition.

- Chan, Ying-kit (4 October 2016). "Eugenics in Postcolonial Singapore". Blynkt.com. Berlin. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (16 August 1984). "Between You and Your Genes". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "Singapore: Population Control Policies". Library of Congress Country Studies (1989). Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- Jacobson, Mark (January 2010). "The Singapore Solution". National Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on 19 December 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- Proclamation of Tehran, Final Act of the International Conference on Human Rights, Teheran, 22 April to 13 May 1968, U.N. Doc. A/CONF. 32/41 at 3 (1968) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations, May 1968 – "16. The protection of the family and of the child remains the concern of the international community. Parents have a basic human right to determine freely and responsibly the number and the spacing of their children ...."

- Harris John (1998). Rights and reproductive choice. In: Holm S, Harris John, eds. The future of human reproduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.5–37

- Paul, Diane (2001). "Where Libertarian Premises Lead." The American Journal of Bioethics 1(1), 26-27

- Robertson, John A. (1983). "Procreative Liberty and the Control of Conception, Pregnancy, and Childbirth." Virginia Law Review, 69(3), 405–464. doi:10.2307/1072766

- Robertson, John A. (1996). Children of Choice: Freedom and the New Reproductive Technologies. Princeton University Press

- Gutmann, Amy (ed. Michael Ignatieff) (2001). Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Fenton, Elizabeth (2008). "Genetic Enhancement – a Threat to Human Rights?" Bioethics 22(1), 2147483647–0. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00564.x

- Mcconnell, Terrance (2010). "Genetic Enhancement, Human Nature, and Rights." Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 35(4), 415–428. doi:10.1093/jmp/jhq034 PMID: 20639283

- ^ Galton, David (2002). Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century. London: Abacus. p. 48. ISBN 0349113777.

- Lively, Curtis M. (June 2010). "The Effect of Host Genetic Diversity on Disease Spread". The American Naturalist. 175 (6): E149 – E152. doi:10.1086/652430. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 20388005.

- King, K. C.; Lively, C. M. (June 2012). "Does genetic diversity limit disease spread in natural host populations?". Heredity. 109 (4): 199–203. doi:10.1038/hdy.2012.33. PMC 3464021. PMID 22713998.

- ^ Withrock, Isabelle (2015). "Genetic diseases conferring resistance to infectious diseases". Genes & Diseases. 2 (3): 247–254. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2015.02.008. PMC 6150079. PMID 30258868.

- Shermer, Michael (2014). "THE SKEPTIC’S CHAPLAIN: RICHARD DAWKINS AS A FOUNTAINHEAD OF SKEPTICISM", Skeptic magazine

- Dawkins, Richard (20 November 2006). "From the Afterword". The Herald. Glasgow. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Heterozygote test / Screening programmes – DRZE". Drze.de. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Fatal Gift: Jewish Intelligence and Western Civilization". Archived from the original on 13 August 2009.

- "Social Origins of Eugenics". Eugenicsarchive.org. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Carlson, Elof Axel (2002). "Scientific Origins of Eugenics". Image Archive on the American Eugenics Movement. Dolan DNA Learning Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- Leonard, Thomas C. (Tim) (Fall 2005). "Retrospectives: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (4): 207–224. doi:10.1257/089533005775196642. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- Stearns, F. W. (2010). "One Hundred Years of Pleiotropy: A Retrospective". Genetics. 186 (3): 767–773. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.122549. PMC 2975297. PMID 21062962.

- Jones, A. (2000). "Effect of eugenics on the evolution of populations". European Physical Journal B. 17 (2): 329–332. Bibcode:2000EPJB...17..329P. doi:10.1007/s100510070148. S2CID 122344067.

- Caleb, Amanda (27 January 2023). "Eugenics and (Pseudo-) Science". The Holocaust: Remembrance, Respect, and Resilience. Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- Worrall, Simon (24 July 2016). "The Gene: Science's Most Dangerous Idea". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- White, Susan (28 June 2017). "LibGuides: The Sociology of Science and Technology: Pseudoscience". Library of University of Princeton. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Currell, Susan; Cogdell, Christina (2006). Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in The 1930s. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. p. 203. ISBN 9780821416914.

- Ladd-Taylor, Molly (2001). "Eugenics, Sterilisation and the Modern Marriage in the USA: The Strange Career of Paul Popenoe". Gender & History 13(2): 298-327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.00230

- Dokötter, Frank (1998). "Race Culture: Recent Perspectives on the History of Eugenics". American Historical Review 103: 467-78

- ^ Gillette, Aaron (2007). Eugenics and the nature-nurture debate in the twentieth century (PDF) (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- Bentwich, M. (2013). "On the inseparability of gender eugenics, ethics, and public policy: An Israeli perspective". American Journal of Bioethics. 13 (10): 43–45. doi:10.1080/15265161.2013.828128. PMID 24024807. S2CID 46334102.

- Fischer, B. A. (2012). "Maltreatment of people with serious mental illness in the early 20th century: A focus on Nazi Germany and eugenics in America". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 200 (12): 1096–1100. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318275d391. PMID 23197125. S2CID 205883145.

- Hoge, S. K.; Appelbaum, P. S. (2012). "Ethics and neuropsychiatric genetics: A review of major issues". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (10): 1547–1557. doi:10.1017/S1461145711001982. PMC 3359421. PMID 22272758.

- Witzany, G. (2016). "No time to waste on the road to a liberal eugenics?". EMBO Reports. 17 (3): 281. doi:10.15252/embr.201541855. PMC 4772985. PMID 26882552.

- Baird, S. L. (2007). "Designer babies: Eugenics repackaged or consumer options?". Technology Teacher. 66 (7): 12–16.

- Roberts, M. A. "The Nonidentity Problem". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Kerr, Anne; Shakespeare, Tom (2002). Genetic Politics: from Eugenics to Genome. Cheltenham: New Clarion. ISBN 9781873797259.

- Shakespeare, Tom (1995). "Back to the Future? New Genetics and Disabled People". Critical Social Policy. 46 (44–45): 22–35. doi:10.1177/026101839501504402. S2CID 145688957.

- Darnovsky, Marcy (2001). "Health and human rights leaders call for an international ban on species-altering procedures". Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2006.

- Annas, George; Andrews, Lori; Isasi, Rosario (2002). "Protecting the endangered human: Toward an international treaty prohibiting cloning and inheritable alterations". American Journal of Law & Medicine. 28 (2–3): 151–78. doi:10.1017/S009885880001162X. PMID 12197461. S2CID 233430956. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- McKibben, Bill (2003). Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age. Times Books. ISBN 9780805070965. OCLC 237794777.

- Comfort, Nathaniel (12 November 2012). "The Eugenics Impulse". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Comfort, Nathaniel (25 September 2012). The Science of Human Perfection: How Genes Became the Heart of American Medicine. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300169911.

- Wilkinson, Stephen; Garrard, Eve (2013). Eugenics and the Ethics of Selective Reproduction (PDF). Keele University. ISBN 9780957616004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Rawls, John (1999) . A theory of justice (revised ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 92. ISBN 0674000781.

In addition, it is possible to adopt eugenic policies, more or less explicit. I shall not consider questions of eugenics, confining myself throughout to the traditional concerns of social justice. We should note, though, that it is not in general to the advantage of the less fortunate to propose policies which reduce the talents of others. Instead, by accepting the difference principle, they view the greater abilities as a social asset to be used for the common advantage. But it is also in the interest of each to have greater natural assets. This enables him to pursue a preferred plan of life. In the original position, then, the parties want to insure for their descendants the best genetic endowment (assuming their own to be fixed). The pursuit of reasonable policies in this regard is something that earlier generations owe to later ones, this being a question that arises between generations. Thus over time a society is to take steps at least to preserve the general level of natural abilities and to prevent the diffusion of serious defects.

- Shaw, p. 147. Quote: "What Rawls says is that "Over time a society is to take steps to preserve the general level of natural abilities and to prevent the diffusion of serious defects." The key words here are "preserve" and "prevent". Rawls clearly envisages only the use of negative eugenics as a preventive measure to ensure a good basic level of genetic health for future generations. To jump from this to "make the later generations as genetically talented as possible," as Pence does, is a masterpiece of misinterpretation. This, then, is the sixth argument against positive eugenics: the Veil of Ignorance argument. Those behind the Veil in Rawls' original Position would agree to permit negative, but not positive eugenics. This is a more complex variant of the consent argument, as the Veil of Ignorance merely forces us to adopt a position of hypothetical consent to particular principles of justice."

- Harding, John R. (1991). "Beyond Abortion: Human Genetics and the New Eugenics". Pepperdine Law Review. 18 (3): 489–491. PMID 11659992. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

Rawls arrives at the difference principle by considering how justice might be drawn from a hypothetical 'original position.' A person in the original position operates behind a 'veil of ignorance' that prevents her from knowing any information about herself such as social status, physical or mental capabilities, or even her belief system. Only from such a position of universal equality can principles of justice be drawn. In establishing how to distribute social primary goods, for example, 'rights and liberties, powers and opportunities, income and wealth" and self-respect, Rawls determines that a person operating from the original position would develop two principles. First, liberties ascribed to each individual should be as extensive as possible without infringing upon the liberties of others. Second, social primary goods should be distributed to the greatest advantage of everyone and by mechanisms that allow equal opportunity to all. ... Genetic engineering should not be permitted merely for the enhancement of physical attractiveness because that would not benefit the least advantaged. Arguably, resources should be concentrated on genetic therapy to address disease and genetic defects. However, such a result is not required under Rawls' theory. Genetic enhancement of those already intellectually gifted, for example, might result in even greater benefit to the least advantaged as a result of the gifted individual's improved productivity. Moreover, Rawls asserts that using genetic engineering to prevent the most serious genetic defects is a matter of intergenerational justice. Such actions are necessary in terms of what the present generation owes to later generations.

- Koboldt, Daniel (29 August 2017). "The Science of Sci-Fi: How Science Fiction Predicted the Future of Genetics". Outer Places. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- Edwards, Richard (27 June 2023). "Star Trek: Strange New Worlds: Augments, Illyrians and the Eugenics Wars". Space.com. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- Ebert, Roger (24 October 1997). "Gattaca". rogerebert.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Jabr, Ferris (2013). "Are We Too Close to Making Gattaca a Reality?". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Pope, Marcia; McRoberts, Richard (2003). Cambridge Wizard Student Guide Gattaca. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521536154.

- Kirby, D.A. (2000). "The New Eugenics in Cinema: Genetic Determinism and Gene Therapy in GATTACA". Science Fiction Studies. 27. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- Silver, Lee M. (1997). "Genetics Goes to Hollywood". Nature Genetics. 17 (3): 260–261. doi:10.1038/ng1197-260. S2CID 29335234.

- Anderson, W. French (1990). "Genetics and Human Malleability." The Hastings Center Report, 20(1), 21–24. doi:10.2307/3562969 p.24

- Zimmer, Carl (10 November 2008). "Now: The Rest of the Genome". The New York Times.

- Kirby, David A. (July 2000). "The New Eugenics in Cinema: Genetic Determinism and Gene Therapy in "GATTACA"". Science Fiction Studies. 27 (2): 193–215. JSTOR 4240876.

- ^ Hughes, James (2004). Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-4198-1.

- Plomin, Robert (13 November 2018). Blueprint: How DNA Makes Us Who We Are. MIT Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9780262039161. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

Notes

- He concretely intended it to replace the word "stirpiculture", which he had used previously but which had come to be mocked due to its perceived sexual overtones.

- Though the origins of the concept also had to do with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance and the theories of August Weismann.

- Note for example that:

"There is widespread religious disagreement among the individuals to whom these rights apply. Atheists will reject the notion that human beings are sacred, since ‘sacred’ implies a God whose creations are sacred, while non-Christians will reject the notion that humans are sacred in the eyes of a single Christian God. Humans disagree about what kinds of being they are and what makes them special, if anything."

- Accordingly, Lee M. Silver stated that "Gattaca is a film that all geneticists should see if for no other reason than to understand the perception of our trade held by so many of the public-at-large".

- In the context of this film, James Hughes, has similarly come to argue that:

Control over human nature is unlikely to lead to neglect of environmental improvement. Society might just ramp up kids’ intelligence instead of providing them with better-funded schools. But that wouldn’t work very well, since smarter kids would only make the inadequacies of the schools more glaring. We will fix obesity genes, but people will still have to eat right and exercise. Fixes for lung cancer and skin cancer are unlikely to dry up our concern about industrial pollution and the ozone layer.

Further reading

- Agar, Nicholas (2004). Liberal Eugenics: In Defense of Human Enhancement. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Agar, Nicholas (2019). "Why we Should Defend Gene Editing as Eugenics". Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 34 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1017/S0963180118000336. PMID 30570459. S2CID 58195676.

- Anomaly, Jonathan (2020). Creating Future People The Ethics of Genetic Enhancement. Routledge, ISBN 9780367203122

- Anomaly, Jonathan (2018). "Defending eugenics: From cryptic choice to conscious selection." Monash Bioethics Review 35 (1-4):24-35. doi:10.1007/s40592-018-0081-2

- Buchanan, Allen (2017). Better than Human: The Promise and Perils of Deliberate Biomedical Enhancement. "Philosophy in Action" series. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190664046.

- Cavaliere, Giulia (2018). "Looking into the Shadow: Eugenics arguments in debates about reproductive technologies". Monash Bioethics Review. 36 (1–4): 1–22. doi:10.1007/s40592-018-0086-x. PMC 6336759. PMID 30535862.

- Daar, Judith (2017). The New Eugenics: Selective Breeding in an Era of Reproductive Technologies. Yale University Press.

- Galton, David J. (2002). Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century. London: Abacus. ISBN 9780349113777.

- Gantsho, Luvuyo (2022). "The principle of procreative beneficence and its implications for genetic engineering." Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 43 (5):307-328. doi:10.1007/s11017-022-09585-0

- Goldberg, Jonah (2007). Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, from Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385511841.

- Harris, John (2009). "Enhancements are a Moral Obligation." In J. Savulescu & N. Bostrom (Eds.), Human Enhancement, Oxford University Press, pp. 131–154

- Joseph, Jay (2004). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology Under the Microscope. New York: Algora. ISBN 9780875863436. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009.

- Kamm, Frances (2010). "What Is And Is Not Wrong With Enhancement?" In Julian Savulescu & Nick Bostrom (eds.), Human Enhancement. Oxford University Press.

- Kamm, Frances (2005). "Is There a Problem with Enhancement?", The American Journal of Bioethics, 5(3), 5-14. PMID 16006376 doi:10.1080/15265160590945101

- Lynn, Richard (1997). Dysgenics: Genetic Deterioration in Modern Populations (PDF). Praeger Publishers. ISBN 9780275949174.

- Lynn, Richard (2001). Eugenics: A Reassessment (PDF). Praeger Publishers. ISBN 9780275958220.

- Maranto, Gina (1996). Quest for perfection: the drive to breed better human beings. New York: Scribner. ISBN 9780684800295.

- Ranisch, Robert (2022). "Procreative Beneficence and Genome Editing", The American Journal of Bioethics, 22(9), 20–22. doi:10.1080/15265161.2022.2105435

- Robertson, John (2021). Children of Choice: Freedom and the New Reproductive Technologies. Princeton University Press, doi:10.2307/j.ctv1h9dhsh.