This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Peacedance (talk | contribs) at 01:05, 26 November 2014 (→top: changed). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:05, 26 November 2014 by Peacedance (talk | contribs) (→top: changed)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Semitic" redirects here. For the group of related languages, see Semitic languages.| This article currently links to a large number of disambiguation pages (or back to itself). Please help direct these ambiguous links to articles dealing with the specific meaning intended. Read the FAQ. (November 2014) |

In studies of linguistics and ethnology, the term Semitic (from the Biblical "Shem", Template:Lang-he) was first used to refer to a family of languages native to West Asia (the Middle East). The languages evolved and spread to Asia Minor, North Africa, The Horn of Africa and Malta, and are now referred to cumulatively as the Semitic languages. The languages include the ancient and modern forms of Ahlamu; Akkadian (including Assyrian and Babylonian dialects); Amharic; Amalekite; Ammonite; Amorite; Arabic; Aramaic/Syriac; the Canaanite languages (Phoenician, Punic or Carthaginian and Hebrew); Assyrian; Chaldean; Eblaite; Edomite; Ge'ez; Old South Arabian; Modern South Arabian languages; Maltese; Mandaic; Moabite; Proto-Sinaitic; Sutean; Syriac; Tigre and Tigrinya; and Ugaritic, among others.

As language studies are interwoven with cultural studies, the term also came to describe the extended cultures and ethnicities, as well as the history of these varied peoples as associated by close geographic and linguistic distribution. Today, the word "Semite" may be used to refer to any member of any of a number of peoples of ancient Middle East including the Akkadians, Assyrians, Arameans, Phoenicians, Hebrews (Jews), Arabs, and their descendants.

Origin

A Semite is a member of any of various ancient and modern Semitic-speaking peoples, mostly originating in the Near East, including; Akkadians (Assyrians and Babylonians), Ammonites, Amorites, Arameans, Chaldeans, Canaanites (including Hebrews/Israelites/Jews/Samaritans and Phoenicians/Carthaginians), Eblaites, Dilmunites, Edomites, Amalekites, Turukku, Ethiopian Semites, Hyksos, Arabs, Nabateans, Maltese, Mandaeans, Mhallami, Moabites, Shebans, Meluhhans, Maganites, Ubarites, Sabians and Ugarites. It was proposed at first to refer to the languages related to Hebrew by Ludwig Schlözer, in Eichhorn's "Repertorium", vol. VIII (Leipzig, 1781), p. 161. Through Eichhorn the name then came into general usage (cf. his "Einleitung in das Alte Testament" (Leipzig, 1787), I, p. 45). In his "Geschichte der neuen Sprachenkunde", pt. I (Göttingen, 1807) it had already become a fixed technical term.

The word "Semitic" is derived from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in Genesis 5, Genesis 6, Genesis 1021, or more precisely from the Greek derivative of that name, namely Σημ (Sēm); the noun form referring to a person is Semite.

The concept of "Semitic" peoples is derived from Biblical accounts of the origins of the cultures known to the ancient Hebrews. In an effort to categorise the peoples known to them, those closest to them in culture and language were generally deemed to be descended from their supposed forefather Shem.

In Genesis 10:21–31, Shem is described as the father of Aram, Ashur, and Arpachshad: the Biblical ancestors of the Arabs, Aramaeans, Assyrians, Babylonians, Chaldeans, Sabaeans, and Hebrews, etc., all of whose languages are fairly closely related; the language family containing them was therefore named "Semitic" by linguists.

The Canaanites, Amalekites, Edomites, Ammonites, Suteans and Amorites also spoke languages very closely related to Hebrew (closer in fact than the languages of the Assyrians, Babylonians, Arameans and Chaldeans) and attested in writing earlier, and are therefore termed Semitic in linguistics, despite being described in Genesis as sons of Ham. Shem is also described in Genesis as the father of Elam and Lud (Lydians). However the Elamite language is certainly not classified as Semitic, but is a language isolate, while the Lydians spoke an Indo-European language. Genesis makes no claims that all descendants of Shem necessarily preserved a similar language, indicating only that the languages of all peoples became thoroughly confused following the failure of the Tower of Babel in Babylon. However, in actuality, many differing languages and nations have been proven to have existed long before Babylon was even founded.

A large number of Non-Semitic speaking peoples also inhabited the same general regions as the Semites;, these included speakers of Language Isolates, stand alone languages not part of a greater language family, and unrelated to any other language, including to other isolates. These include Sumerians, Elamites, Hattians, Hurrians, Lullubi, Gutians, Urartians and Kassites. Indo-European language speakers included; Hittites, Greeks, Luwians, Mitanni, Kaskians, Phrygians, Lydians, Philistines, Persians, Medes, Scythians, Cimmerians, Parthians, Cilicians and Armenians, and Kartvelian speakers included Colchians, Tabalites and Georgians.

History

The region of origin of the reconstructed Proto-Semitic language, ancestral to historical and modern Semitic languages in the Middle East, is still uncertain and much debated. However, a recent Bayesian analysis identified an origin for Semitic languages in the Levant (modern Syria and Lebanon) around 3750 BC with a later single introduction from what is now Southern Arabia into the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia) around 800 BC. Other theories include an origin in either Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula or North Africa. The Semitic language family is also considered a component of the larger Afroasiatic macro-family of languages. Identification of the hypothetical proto-Semitic region of origin is therefore dependent on the larger geographic distributions of the other language families within Afroasiatic, whose origins are also hotly debated.

The earliest positively proven historical attestation of any Semitic people comes from 30th century BC Mesopotamia, with the East Semitic Akkadian speaking peoples of the Kish civilization, entering the region originally dominated by the non-Semitic Sumerians (who spoke a language isolate). The earliest known Akkadian inscription was found on a bowl at Ur, addressed to the very early pre-Sargonic king Meskiang-nuna of Ur by his queen Gan-saman, who is thought to have been from Akkad. However, some of the names appearing on the Sumerian king list as prehistoric rulers of Kish have been held to indicate a Semitic presence even before this, as early as the 30th or 29th century BC. By the mid 3rd millennium BC, many states and cities in Mesopotamia had come to be ruled or dominated by Akkadian speaking Semites, including Assyria, Eshnunna, Akkad, Kish, Isin, Ur, Uruk, Adab, Nippur, Ekallatum, Nuzi, Akshak, Eridu and Larsa.

During this period (circa 27th to 26th century BC), another East Semitic speaking people, the Eblaites, appear in historical record from northern Syria, founding the state of Ebla, whose language was closely related to the Akkadian of Mesopotamia.

The Akkadians, Assyrians and Eblaites were the first Semitic people to use writing, using the Cuneiform script originally developed by the Sumerians circa 3500 BC, with the first writings in Akkadian dating from circa 2800 BC. The last Akkadian inscriptions date from the late 1st century AD, and Cuneiform script in the 2nd century AD, both in Mesopotamia.

Mesopotamia is generally held to be the cradle of civilisation, where writing, the wheel, the first organised nation states and city states arose during the mid 4th millennium BC, and where the first written evidence of Mathematics, Astronomy, Organised religion, Written Law, Astrology and Medicine are to be found.

The Sumero-Akkadian states that arose throughout Mesopotamia between circa the 36th century BC and the 24th century BC were the most advanced in the world at the time in terms of engineering, architecture, agriculture, science, medicine, mathematics, astronomy and military technology. Many had highly sophisticated Socioeconomic structures, with the worlds earliest examples of Written Law, together with structurally advanced and complex trading, business and taxation systems, a well structured civil administration, currency and detailed record keeping. Schools and education existed in many states, Mesopotamian religion was highly organised, and astrology was practiced widely. By the time of the Middle Assyrian Empire in the mid 2nd millennium BC, early examples of zoology, botany and landscaping had emerged, and during the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the early to mid 1st millennium BC, the world's first library was built.

Mesopotamia was the center of many powerful empires which often dominated the Near East and beyond, including; the Akkadian Empire (2335-2154 BC), Neo-Sumerian Empire (2119-2004 BC), Old Assyrian Empire (2035-1750 BC), Babylonian Empire (1792-1740 BC), Middle Assyrian Empire (1365-1020 BC), Neo Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC) and Neo-Babylonian Empire (605-539 BC).

All early Semites across the entire Near East appear to have originally been Polytheist. Mesopotamian religion is the earliest recorded and for three millennia was the most influential, exerting strong influence on the later recorded Canaanite religions then practiced in what is today Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories and the Sinai Peninsula, and also those of the Arameans, Chaldeans, Phoenicians/Carthaginians and Arabs. The influence of Mesopotamian religion can also be found in Armenian, Persian and Graeco-Roman religion and to some degree upon the later Semitic Monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, Mandaeism, Gnosticism and Islam.

Some of the most significant of these Mesopotamian deities were Anu, Ea, Enlil, Enki, Ishtar (Astarte), Ashur, Shamash, Shulmanu, Tammuz, Adad (Hadad), Sin (Nanna), Dagan (Dagon), Ninurta, Nisroch, Nergal, Tiamat, Bel, Ninlil, Zababa, Ashurbel and Marduk, many of whom were to find contemporaries throughout the Near East, and to some degree in Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Greece, North Africa and Rome.

The Akkadian Empire (2335–2193 BC), arguably the first empire in history, enabled the Mesopotamian Semites to unite all of Mesopotamia under one rule, and further spread their dominance and cultural and technological influence over much of the Near East, Asia Minor (Anatolia) and Ancient Iran.

A people known as the Turukku appeared in northwestern Ancient Iran during the Akkadian empire, and appear to have been a synthesis of both Hurrians and East Semites.

Of the West Semitic speaking peoples who occupied what is today Syria (excluding the East Semitic north east), Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, the Palestinian territories and the Sinai peninsula, the earliest references concern the Canaanite speaking Amorites (known as "Martu" or "Amurru" by the Mesopotamians) of northern and eastern Syria, and date from the 24th century BC in Mesopotamian annals. The technologically advanced Sumerians, Akkadians and Assyrians of Mesopotamia mention the West Semitic speaking peoples in disparaging terms;- The MAR.TU who know no grain... The MAR.TU who know no house nor town, the boors of the mountains... The MAR.TU who digs up truffles... who does not bend his knees (to cultivate the land), who eats raw meat, who has no house during his lifetime, who is not buried after death.

However, after initially being prevented from doing so by powerful Assyrian kings of the Old Assyrian Empire intervening from northern Mesopotamia, these Amorites would eventually overrun southern Mesopotamia, and found the state of Babylon in 1894 BC, where they became Akkadianized, adopted Mesopotamian culture and language, and blended into the indigenous population. Babylon became the centre of a short lived but influential Babylonian Empire in the 18th century BC, and subsequent to this southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia, with Babylon superseding the ancient city of Nippur as the primary religious center of southern Mesopotamia. Northern Mesopotamia had long before already coalesced into Assyria. After the fall of the first Babylonian Empire, the far south of Mesopotamia broke away for circa 300 years, becoming the independent Sealand Dynasty.

In the 19th century BC a similar wave of Canaanite-speaking Semites entered Egypt and by the early 17th century BC these Canaanites (known as Hyksos by the Egyptians) had conquered the country, forming the Fifteenth Dynasty, introducing military technology new to Egypt, such as the war chariot.

A number of Pre-Arab Semitic states are mentioned as existing (in what was much later to become known as the Arabian Peninsula) in Akkadian and Assyrian records as colonies of these Mesopotamian powers, such as Meluhha and Dilmun (in modern Bahrain). A number of other non-Arab South Semitic states existed in the far south of the peninsula, such as Sheba/Saba (in modern Yemen), Magan and Ubar (both in modern Oman), although the histories of these states is sketchy (mainly coming from Mesopotamian and Egyptian records), as there was no written script in the region at this time.

Proto-Canaanite texts from northern Canaan and the Levant (modern Lebanon and Syria) around 1500 BC yield the first undisputed attestations of a written West Semitic language (although earlier testimonies are found in Mesopotamian annals concerning Amorite, and possibly preserved in Middle Bronze Age alphabets, such as the Proto-Sinaitic script from the late 19th century BC), followed by the much more extensive Ugaritic tablets of northern Syria from the late 14th century BC in the city-state of Ugarit in north west Syria. Ugaritic was a West Semitic language, fairly closely related to, and part of the same general language family as the tongues of the Amorites, Canaanites, Phoenicians, Moabites, Edomites and Israelites.

The Shasu appear in Egyptian records circa 14th century BC, as a semi-nomadic Canaanite speaking people inhabiting Moab and northern Edom (a region stretching from the Jezreel Valley to Ashkelon and the Sinai), and a number of scholars believe the Shasu were synonymous with the Hebrews, who went on to eventually found Israel.

The appearance of nomadic Semitic Aramaeans and Suteans in historical record also dates from the late 14th century BC, the Arameans coming to dominate an area roughly corresponding with modern Syria (which became known as Aram or Aramea), subsuming the earlier Amorites, and founding states such as Aram-Damascus, Luhuti, Bit Agusi, Hamath, Aram-Naharaim, Paddan-Aram, Aram-Rehob, and Zobah, while the Suteans occupied the deserts of south eastern Syria and north eastern Jordan.

A Canaanite group known as the Phoenicians came to dominate the coasts of Syria, Lebanon and south west Turkey from the 13th century BC, founding city states such as Tyre, Sidon, Byblos Simyra, Arwad, Berytus (Beirut), Antioch and Aradus, eventually spreading their influence throughout the Mediterranean, including building colonies in Malta, Sicily, the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain), and the coasts of North Africa, founding the major city state of Carthage (in modern Tunisia) in the 9th century BC.

The Phoenicians created the Phoenician alphabet in the 12th century BC, which would eventually supersede Cuneiform. Phoenician became one of the most widely used writing systems, spread by Phoenician merchants across the Mediterranean world and beyond, where it evolved and was assimilated by many other cultures. The still extant Aramaic alphabet, a modified form of Phoenician script, was the ancestor of modern Hebrew, Syriac/Assyrian and Arab scripts, stylistic variants and descendants of the Aramaic script. The Greek alphabet (and by extension its descendants such as the Latin, the Cyrillic and the Egyptian Coptic scripts), was a direct successor of Phoenician, though certain letter values were changed to represent vowels. Old Italic, Anatolian, Armenian, Georgian and Paleohispanic scripts are also descendant of Phoenician script.

Between the 13th and 11th centuries BC, a number of small Canaanite speaking states arose in Southern Canaan, an area approximately corresponding to modern Israel, Jordan, the Palestinian territories and Sinai Peninsula. These were the lands of the Edomites, Moabites, Hebrews/Israelites/Judaeans/Samaritans, Ammonites and Amalekites, all of whom spoke closely related west Semitic Canaanite languages.

Edom and Moab were first to appear in historical record during the mid to late 13th century BC, both coming into conflict with Egypt. The Hebrews (who spoke a Canaanite dialect) make an appearance in historical record, with the founding of the state of Israel in the late 11th century BC in southern Canaan. Later, a part of Israel broke away, becoming Judea, with a further Jewish kingdom Samarra (the land of the Samaritans) also founded as a puppet kingdom by the Assyrians.

In Israel the very first example of monotheism gradually evolved with the founding of Judaism and the belief in one single god, Yahweh. The Hebrew language, closely related to the earlier attested Canaanite language of the Phoenicians, would become the vehicle of the religious literature of the Tanakh and Torah, and thus eventually have global ramifications.

Alongside and at the same time as the Hebrews/Israelites, another closely related West Semitic/Canaanite nation of Ammon also appeared, often involved in local rivalries with Israel, as did the Amalekites, who did not appear to have a unified state of their own.

The Chaldeans (not to be confused with modern Chaldean Catholics), closely related to but distinct from the Arameans, followed the pattern of the earlier arriving Arameans and Suteans, and migrated from The Levant into the far south east of Babylonia circa the late 10th or early 9th century BC, where they settled and rapidly became Akkadianised. The Chaldeans are first historically attested in 852 BC in Assyrian records.

The South Semitic Arabs also first appear in record in Assyrian Annals from the mid 9th century BC as desert dwelling nomadic inhabitants of what is today Saudi Arabia. They were regarded as conquered vassals of the Assyrians.

Later still, written evidence of Old South Arabian and Ge'ez (both related to but in reality separate languages to the Arabic language) offer the first written attestations of South Semitic languages in the 8th century BC in Sheba, Ubar and Magan (modern Oman and Yemen). These, along with writing in the form of the Ge'ez script, were later imported to the previously non-Semitic speaking lands of Ethiopia and Eritrea by migrating South Semites from part of Southern Arabia (modern west Yemen) during the 8th and 7th centuries BC, who after intermingling with the native non-Semitic African peoples, gave rise to Ethiopian Semitic speaking peoples, whose languages survive to this day.

The East Semitic Mesopotamian states of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia proved to be not only the oldest, but the most advanced in the Near East and its surrounds, between the mid 24th and late 6th centuries BC, often asserting dominance over the West, Northwest and South Semitic speaking peoples, as well as the Non-Semitic peoples of the region.

The non-Semitic Philistines, (one of the Sea Peoples, and not to be confused with modern Palestinian Arabs) seem to have arrived in southern Canaan sometime in the 12th century. The Philistines are conjectured to have spoken an Indo-European language, as there are possibly Greek, Lydian and Luwian traces in the limited information available about their tongue, although there is no detailed information about their language. An Indo-European Anatolian origin is also supported by Philistine pottery, which appears to have been exactly the same as Mycenaen Greek pottery.

In Egypt, the people were speakers of a stand alone Afroasiatic tongue, a language loosely related to but distinct from those of the Semitic peoples, as were the Berbers of the Sahara and the coasts of North Africa, Semitic Carthage aside. Nilotic peoples such as the Nubians, Kushites and Dinka dwelt to the south of the Egyptians, and Puntites to the south east of Ethiopia.

A number of non-Semitic peoples were eventually absorbed by Semites; The Sumerians were absorbed into the Akkadian speaking Assyro-Babylonian population of Mesopotamia by around 2000 BC, and the Kassites who ruled Babylonia for almost five centuries from the early 16th century BC, eventually blended into the native population. Similarly, the Philistines eventually disappeared into the native Israelite-Canaanite population, and in northern Aram (Syria) and south central Asia Minor, there was a synthesis between the Semitic Arameans and Indo-European Neo-Hittites, with the founding of a number of small Syro-Hittite states fro the 12th century BC until their destruction by Assyria in the 8th and 7th centuries BC.

During the Middle Assyrian Empire (1366-1020 BC) and in particular the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC) much of the Near East, Asia Minor, Caucasus, Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, Ancient Iran and North Africa fell under Assyrian domination. During the 8th century BC the Assyrian emperor Tiglath-Pileser III introduced Aramaic as the lingua franca of their empire, and this language was to remain dominant among Near Eastern Semites until the early Medieval Period. Mesopotamian cities such as Nineveh, Babylon and Ashur (Assur) were the largest in the world during the Iron Age.

The Assyrian Empire collapsed by 605 BC after decades of internal civil war followed by a combined attack on the weakened sate by an alliance of its former subject peoples (their own Babylonian relations, together with the Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians), and after the collapse of the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC, the Semitic peoples found themselves largely under the domination of various Indo-European speaking empires for over twelve centuries; the Achaemenid Empire, Seleucid Empire, Parthian Empire, Roman Empire, Sassanid Empire and Byzantine Empire.

Babylonia was often erroneously referred to as Chaldea from the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire onwards (particularly in Jewish writings), although only the first three or four rulers of the empire were certainly Chaldeans, and the last two rulers were Assyrian. The migrant Chaldeans, like the Amorites, Kassites, Suteans and Arameans of southern Mesopotamia before them, eventually blended into the indigenous population, and wholly disappeared as a distinct people and ethnicity, and Babylonia itself was eventually subsumed into Assyria (Assuristan) by the Sassanid Empire.

During these periods there were spells of varying degrees of independence from the Indo-European empires. In Israel/Judea, the powerful Hasmonean dynasty arose, which at its height expanded into Syria, Jordan and the Sinai. Independent states arose among the Assyrians between the 1st century BC and 4th century AD, such as Adiabene, Osroene, Assur and Hatra, with the Neo-Assyrian state of Osroene becoming the first independent Christian country in history. The Aramean state of Palmyra founded a short lived Palmyrene Empire based in northern Syria in the 3rd century AD, briefly rivalling Rome. The Nabateans, an Aramaic-speaking people of mixed Canaanite, Aramean and pre-Islamic Arab origins appear in the 4th century BC around the Negev, Sinai Peninsula and northern Arabia, forming an independent Nabatea between the 2nd century BC and 2nd century AD, with its capital at Petra. Most notable was the powerful Phoenician state of Carthage which colonised much of the Mediterranean coastline, including those of eastern Spain and southern Portugal, southern France, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria as well as Sicily, Malta, Gibraltar, Sardinia and Corsica. For centuries it rivaled the Roman Empire before being finally destroyed in the 3rd century AD.

The Mandeans, a gnostic ethno-religious sect venerating John the Baptist as the true Messiah, appear in the 1st century AD first in Assyria, and then Southern Mesopotamia. Their origins are unclear, but most scholars believe that they are originally a Canaanite or Aramean people originating from around the River Jordan who mixed with Mesopotamians, while others believe them to be native Mesopotamians.

By the 1st century AD various Aramaic dialects had come to dominate an area stretching from eastern Asia Minor in the north to the northern Arabian Peninsula in the south, and from Assyria, Mesopotamia and north western Persia in the east, to the Eastern coasts of the Mediterranean in the west. Aramaic inscriptions have also been found as far afield as ancient England and Scotland on and around the region of Hadrians Wall, written by Assyrian and Aramean soldiers of the Roman army.

Particularly Semitic religions such as Judaism, Christianity, Mandaeism, Sabianism, Manicheanism and Gnosticism took root among the Semites, with Judaism long centered in Judaea (Israel) and Mesopotamia, and Christianity first spread initially among the largely Aramaic speaking Semitic races of Judaea, Syria, Assyria, Babylonia, Nabatea and Phoenicia during the 1st century AD, an area encompassing the modern states of Israel, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Kuwait, south eastern Turkey and the Palestinian territories. Syriac Christianity and the Syriac language largely originatd and centered in areas outside of Roman control, in Persian-occupied Assyria (Athura/Assuristan), from whence in the form of the Assyrian Church of the East and Nestorianism, it spread to The Levant, Central Asia, India and China. Coptic Christianity spread from Egypt to the Ethiopian Semites and to the Nilotic peoples of The Sudan by the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. Mandaeism and Sabianism were centered in Assyria and Mesopotamia, and gnostic sects were to be found all over the Semitic world.

With the advent of the Arab Islamic conquest of the 7th and 8th centuries AD, the hitherto largely uninfluential Arabic language (and Islamic culture) slowly but surely replaced many (but not all) of the indigenous Semitic languages and cultures of the Near East. Both the Near East and North Africa saw an influx of Muslim Arabic people from the Arabian Peninsula, followed later by non-Semitic Muslim Iranic and Turkic peoples. The previously dominant Aramaic dialects gradually began to be sidelined, however descendant dialects of Aramaic, including Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, survive to this day among the Assyrians (and Mandaeans) of Northern Iraq, Northwestern Iran, Northeastern Syria and Southeastern Turkey, with the dialects of the Assyrians still to this day containing hundreds of Akkadian loanwords and an Akkadian grammatical structure.

Long extant Semitic geopolitical regions such as Judaea, Assyria, Phoenicia, Carthaginia and Syria/Aramea were dissolved by the Arabs. Indigenous Semitic peoples became citizens in a greater Arab Islamic state, and those who resisted conversion to Islam had certain restrictions imposed upon them. They were excluded from specific duties assigned to Muslims, did not enjoy certain political rights reserved to Muslims, their word was not equal to that of a Muslim in legal matters, they were subject to payment of a special tax (jizyah), they were banned from spreading their religions further in Muslim ruled lands on pain of death, but were also expected to adhere to the same laws of property, contract and obligation as the Muslim Arabs.

The Arabs spread their South Semitic language to North Africa where it gradually replaced Coptic and Berber (although Berber is still largely extant), and for a time to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain, Portugal and Gibraltar).

A number of South Arabian languages distinct from Arabic still survive, such as Soqotri, Mehri and Shehri which are mainly spoken in Socotra, Yemen and Oman, and are likely descendants of the languages spoken in the ancient Pre Arab and non-Arab kingdoms of Sheba, Magan, Ubar, Meluhha and Dilmun.

By the 21st century AD, people identifying as Arabs now make up the largest population of Semites in the Near East, followed by large numbers of non-Semitic Berbers in North Africa and Ethiopian Semites in the Horn of Africa.

However a significant number of the once dominant indigenous, ancient pre-Arab and pre-Islamic Semitic peoples of the Middle East maintain their identities to this day, including the Jews, Copts, Maronites, Assyrians, Syriac-Arameans, Mandeans etc., despite being often persecuted ethnic and religious minorities.

In Israel, the majority population are Hebrew-speaking ethnic Jews, with a tiny minority of Samaritans still extant.

In Iraq and the areas of northeast Syria, northwest Iran and southeast Turkey bordering northern Iraq, the indigenous Assyrians (also known theologically as Chaldo-Assyrians) still maintain their Akkadian-influenced dialects of Eastern Aramaic as spoken and written tongues, together with their ancient forms of Eastern Christianity. In these same areas the Mandaeans retain their distinct pre-Arab Mandaic language and Gnostic religion.

Among the Syriac Christians and Mhallami of modern Syria, the advocacy of a pre-Arab Aramean or Syriac-Aramean identity is still strong, although only tiny minorities now speak their native Western Aramaic tongue.

In Lebanon and some coastal regions of Syria the concept of Phoenicianism is endorsed, particularly by Maronite Christians who reject Arab identity and instead assert their ethnic roots lie with the pre-Arab and pre-Islamic Canaanites and Phoenicians.

Semitic-speaking peoples

The following is a list of ancient and modern Semitic speaking peoples:

- Mandaeans

- Akkadians (Assyrians/Babylonians) — migrated into Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium BC and amalgamate with non-Semitic Mesopotamian (Sumerian) populations into the Assyrians and Babylonians of the Late Bronze Age. The remnants of these people became the modern Assyrians (also known as Chaldo-Assyrians) of Iraq, Iran, south eastern Turkey and northeast Syria.

- Eblaites — 23rd century BC

- Chaldeans — appeared in southern Mesopotamia circa 1000 BC and eventually disappeared into the general Babylonian population.

- Aramaeans — 16th to 8th centuries BC / Akhlames (Ahlamu) 14th century BC.

- Mhallami – Tiny minority of Syriac-Arameans who converted to secular Islam but retained Syriac identity

- Ugarites, 14th to 12th centuries BC

- Suteans – 14th century BC

- Canaanite-speaking nations of the early Iron Age:

- Amorites — 20th century BC

- Ammonites

- Edomites

- Amalekites

- Hebrews/Israelites — founded the nation of Israel which later split into the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. The remnants of these people became the Jews and the Samaritans.

- Moabites

- Phoenicians/Carthaginians — founded Mediterranean colonies including Tyre, Sidon and Carthage. The remnants of these people became the modern inhabitants of Lebanon.

- Old South Arabian speaking peoples

- Sabaeans of Yemen — 9th to 1st centuries BC

- Shebans

- Ubarites

- Maganites

- Ethio-Semitic speaking peoples

- Aksumites — 4th century BC to 7th century AD

- Arabs, Old North Arabian speaking Bedouins

- Gindibu's Arabs 9th century BC

- Qedarites tribe 7th-century BC descendants of the Ismaelites and descendant of the Patriarch Ismaels son Kedar

- Lihyanites — 6th to 1st centuries BC

- Thamud people — 2nd to 5th centuries AD

- Ghassanids — 3rd to 7th centuries AD

- Nabataeans — Mix of Aramaiac and Arabic speakers

- Maltese

Languages

Main article: Semitic languages

The modern linguistic meaning of "Semitic" is derived from (though not identical to) Biblical usage. In a linguistic context the Semitic languages are a subgroup of the larger Afroasiatic language family (according to Joseph Greenberg's widely accepted classification) and include, among others: Akkadian, the ancient language of Babylon and Assyria; Amorite, Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia; Tigrinya, a language spoken in Eritrea and in northern Ethiopia; Arabic; Aramaic, still spoken in Iraq, Iran, Syria, Turkey and Armenia by Assyrian-Chaldean Christians and Mandaeans; Canaanite; Ge'ez, the ancient language of the Eritrean and Ethiopian Orthodox scriptures which originated in Yemen; Hebrew; Maltese; Phoenician or Punic; Syriac (a form of Aramaic); and South Arabian, the ancient language of Sheba, which today includes Mehri, spoken by only tiny minorities on the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula.

Wildly successful as second languages far beyond their numbers of contemporary first-language speakers, a few Semitic languages today are the base of the sacred literature of some of the world's great religions, including Islam (Arabic), Judaism (Hebrew and Aramaic), and Syriac and Ethiopian Christianity (Aramaic/Syriac and Ge'ez). Millions learn these as a second language (or an archaic version of their modern tongues): many Muslims learn to read and recite Classical Arabic, the language of the Qur'an, and many Jews all over the world outside of Israel with other first languages speak and study Hebrew, the language of the Torah, Midrash, and other Jewish scriptures. Ethnic Assyrian followers of The Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Ancient Church of the East and some Syriac Orthodox Christians, both speak Mesopotamian eastern Aramaic and use it also as a liturgical tongue. The language is also used liturgically by the primarily Arabic speaking followers of the Maronite, Syriac Catholic Church and some Melkite Christians. Arabic itself is the main liturgical language of Byzantine-rite Orthodox Christians in the Middle East, who compose the patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. Mandaic — another dialect of Aramaic — is both spoken and used as a liturgical language by followers of the Mandaean faith.

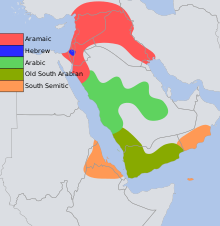

Geography

Semitic peoples and their languages, in ancient historic times (between the 30th and 20th centuries BC), covered a broad area which encompassed what are today the modern states and regions of Iraq, Syria, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinian territories, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Yemen, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and the Sinai Peninsula and Malta.

The earliest historic (written) evidences of them are found in the Fertile Crescent (Mesopotamia) circa the 30th century BC, an area encompassing the Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian civilizations along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (modern Iraq), followed by historical written evidence from the Levant, Canaan, Sinai Peninsula southern Asia Minor and the Arabian peninsula.

Ethnicity and race

Further information: Archaeogenetics of the Near East, Caucasian race, Hamitic race, and Scientific racism

In historical race classifications, the Semitic peoples are considered to be of Caucasoid type, not dissimilar in appearance to the neighbouring Indo-European, Northwest Caucasian, Berber and Kartvelian speaking peoples of the region.

Some recent genetic studies have found (by analysis of the DNA of Semitic-speaking peoples) that they have some common ancestry. Though no significant common mitochondrial results have been found, Y-chromosomal links between modern Semitic-speaking Near-Eastern peoples like Arabs, Hebrews, Mandaeans, Syriacs-Arameans, Samaritans and Assyrians have proved fruitful, despite differences contributed from other groups (see Y-chromosomal Aaron).

Semitic-speaking Near Easterners such as Jews, Assyrians, Arabs, Maronites, Mandaeans, Druze, Samaritans, and Mhallami, from the Fertile Crescent (Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, the Sinai peninsula and the Palestinian Territories), were found to be far more closely related to both each other (and indeed the later arriving non-Semitic speaking Near Easterners, such as Iranians, Anatolians, and Caucasians) than to the Semitic-speakers of the Arabian peninsula, Ethiopian Semites (Amharic and Tigrean speakers), and the Arabic speakers of North Africa.

Genetic studies indicate that modern Jews (Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Mizrahi specifically), Levantine Arabs, Assyrians, Samaritans, Syriacs-Arameans, Maronites, Druze, Mandaeans, and Mhallami, all have an ancient indigenous common Near Eastern heritage which can be genetically mapped back to the ancient Fertile Crescent, but often also display genetic profiles distinct from one another, indicating the different histories of these peoples.

Anti-Semitism and Semiticisation

Main article: AntisemitismThe word "Semite" and most uses of the word "Semitic" relate to any people whose native tongue is, or was historically, a member of the associated language family. The term "anti-Semite", however, came by a circuitous route to refer most commonly to one hostile or discriminatory towards Jews in particular.

Anthropologists of the 19th century such as Ernst Renan readily aligned linguistic groupings with ethnicity and culture, appealing to anecdote, science and folklore in their efforts to define racial character. Moritz Steinschneider, in his periodical of Jewish letters Hamaskir (3 (Berlin 1860), 16), discusses an article by Heymann Steinthal criticising Renan's article "New Considerations on the General Character of the Semitic Peoples, In Particular Their Tendency to Monotheism". Renan had acknowledged the importance of the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia, Israel etc. but called the Semitic races inferior to the Aryan for their monotheism, which he held to arise from their supposed lustful, violent, unscrupulous and selfish racial instincts. Steinthal summed up these predispositions as "Semitism", and so Steinschneider characterised Renan's ideas as "anti-Semitic prejudice".

In 1879 the German journalist Wilhelm Marr, in a pamphlet called Der Weg zum Siege des Germanenthums über das Judenthum ("The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism"), began the politicisation of the term by speaking of a struggle between Jews and Germans. He accused them of being liberals, a people without roots who had Judaized Germans beyond salvation. In 1879 Marr's adherents founded the "League for Anti-Semitism" which concerned itself entirely with anti-Jewish political action.

See also

- Afroasiatic languages

- Battakhin

- Hamitic

- Japhetic

- Proto-Semitic language

- Proto-Sinaitic script

- Sons of Noah

References

- "Semite". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate® Dictionary, Eleventh Edition.

- "Semite". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Semites" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company., Volume XIII

- Ham is also attributed as the ancestor of the "Hittite", a name now used to describe an Indo-European people; however they are so called from the preceding Hattians, who spoke a language isolate.

- Kitchen, A; Ehret, C; Assefa, S; Mulligan, CJ. (2009). "Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East". Proc Biol Sci. 276 (1668): 2703–10. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408. PMC 2839953. PMID 19403539.

- Lucy Wyatt. Approaching Chaos: Could an Ancient Archetype Save C21st Civilization?. p. 120.

- Donald P. Hansen, Erica Ehrenberg. Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. p. 133.

- Andrew George, "Babylonian and Assyrian: A History of Akkadian", In: Postgate, J. N., (ed.), Languages of Iraq, Ancient and Modern. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, pp. 31–71

- Georges Roux — Ancient Iraq

- Adkins 2003, p. 47.

- Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq

- Bottéro (2001:Preface)

- "Assyria". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Julian Jaynes (2000). The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Mariner Books. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- "Amorite (people)". Encyclopedia Britannica online. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 30 November 2012

- ^ Chiera 1934: 58 and 112

- Lloyd, A.B. (1993). Herodotus, Book II: Commentary, 99–182 v. 3. Brill. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-04-07737-9. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Stein, Peter (2005). "The Ancient South Arabian Minuscule Inscriptions on Wood: A New Genre of Pre-Islamic Epigraphy". Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap "Ex Oriente Lux" 39: 181–199.

- Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan and Israel In Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00086-7.

- Redford (1992), p. 272–73, 275.

- a b Rabin 1963, pp. 113–139.

- Maeir 2005, pp. 528–536

- http://www.theguardian.com/culture/charlottehigginsblog/2009/oct/13/hadrians-wall

- Khan 2008, pp. 6

- Clinton Bennett (2005). Muslims and Modernity: An Introduction to the Issues and Debates. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 163. ISBN 082645481X. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- H. Patrick Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 219.

- "Mesopotamian religion – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- "Akkadian language – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- "Aramaean – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- "Akhlame – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- The Races of Europe by Carleton Stevens Coon. From Chapter XI: The Mediterranean World – Introduction: "This third racial zone stretches from Spain across the Straits of Gibraltar to Morocco, and thence along the southern Mediterranean shores into Arabia, East Africa, Mesopotamia, and the Persian highlands; and across Afghanistan into India."

- Nebel, Almut; Filon, Dvora; Brinkmann, Bernd; Majumder, Partha P.; Faerman, Marina; Oppenheim, Ariella (2001). "The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape of the Middle East". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (5): 1095–1112. doi:10.1086/324070. PMC 1274378. PMID 11573163.

- Alshamali, Farida; Pereira, Luísa; Budowle, Bruce; Poloni, Estella S.; Currat, Mathias (2009). "Local Population Structure in Arabian Peninsula Revealed by Y-STR Diversity". Hum Hered. 68: 45–54. doi:10.1159/000210448. PMID 19339785.

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, Alberto Piazza, The History and Geography of Human Genes, p. 243

- "Semite". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate® Dictionary, Eleventh Edition.

- "Semitic". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate® Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Online version.

- "Anti-Semitism". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate® Dictionary, Eleventh Edition.

- Reprinted G. Karpeles (ed.), Steinthal H., Ueber Juden und Judentum, Berlin 1918, pp. 91 ff.

- Published in the Journal Asiatique, 1859

- Alex Bein, The Jewish Question: Biography of a World Problem, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1990, p. 594, ISBN 0-8386-3252-1 – quoting the Hebrew Encyclopaedia Ozar Ysrael, (edited Jehuda Eisenstadt, London 1924, 2: 130ff)

- Moshe Zimmermann, Wilhelm Marr: The Patriarch of Anti-Semitism, Oxford University Press, USA, 1987

External links

- Semitic genetics

- Semitic language family tree included under "Afro-Asiatic" in SIL's Ethnologue.

- The south Arabian origin of ancient Arabs

- The Edomite Hyksos connection

- The perished Arabs

- The Midianites of the north

- Ancient Semitic peoples (video)

| Semitic languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branches | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| East | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| South |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Descendants of Noah in Genesis 10 | |

|---|---|

| Shem and Semitic | |

| Ham and Hamitic | |

| Japheth and Japhetic | |