In mathematics, an autonomous system or autonomous differential equation is a system of ordinary differential equations which does not explicitly depend on the independent variable. When the variable is time, they are also called time-invariant systems.

Many laws in physics, where the independent variable is usually assumed to be time, are expressed as autonomous systems because it is assumed the laws of nature which hold now are identical to those for any point in the past or future.

Definition

An autonomous system is a system of ordinary differential equations of the form where x takes values in n-dimensional Euclidean space; t is often interpreted as time.

It is distinguished from systems of differential equations of the form in which the law governing the evolution of the system does not depend solely on the system's current state but also the parameter t, again often interpreted as time; such systems are by definition not autonomous.

Properties

Solutions are invariant under horizontal translations:

Let be a unique solution of the initial value problem for an autonomous system Then solves Denoting gets and , thus For the initial condition, the verification is trivial,

Example

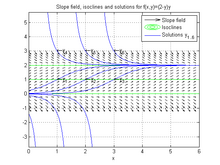

The equation is autonomous, since the independent variable () does not explicitly appear in the equation. To plot the slope field and isocline for this equation, one can use the following code in GNU Octave/MATLAB

Ffun = @(X, Y)(2 - Y) .* Y; % function f(x,y)=(2-y)y

= meshgrid(0:.2:6, -1:.2:3); % choose the plot sizes

DY = Ffun(X, Y); DX = ones(size(DY)); % generate the plot values

quiver(X, Y, DX, DY, 'k'); % plot the direction field in black

hold on;

contour(X, Y, DY, , 'g'); % add the isoclines(0 1 2) in green

title('Slope field and isoclines for f(x,y)=(2-y)y')

One can observe from the plot that the function is -invariant, and so is the shape of the solution, i.e. for any shift .

Solving the equation symbolically in MATLAB, by running

syms y(x); equation = (diff(y) == (2 - y) * y); % solve the equation for a general solution symbolically y_general = dsolve(equation);

obtains two equilibrium solutions, and , and a third solution involving an unknown constant ,

-2 / (exp(C3 - 2 * x) - 1).

Picking up some specific values for the initial condition, one can add the plot of several solutions

% solve the initial value problem symbolically

% for different initial conditions

y1 = dsolve(equation, y(1) == 1); y2 = dsolve(equation, y(2) == 1);

y3 = dsolve(equation, y(3) == 1); y4 = dsolve(equation, y(1) == 3);

y5 = dsolve(equation, y(2) == 3); y6 = dsolve(equation, y(3) == 3);

% plot the solutions

ezplot(y1, ); ezplot(y2, ); ezplot(y3, );

ezplot(y4, ); ezplot(y5, ); ezplot(y6, );

title('Slope field, isoclines and solutions for f(x,y)=(2-y)y')

legend('Slope field', 'Isoclines', 'Solutions y_{1..6}');

text(, , strcat('\leftarrow', {'y_1', 'y_2', 'y_3'}));

text(, , strcat('\leftarrow', {'y_4', 'y_5', 'y_6'}));

grid on;

Qualitative analysis

Autonomous systems can be analyzed qualitatively using the phase space; in the one-variable case, this is the phase line.

Solution techniques

The following techniques apply to one-dimensional autonomous differential equations. Any one-dimensional equation of order is equivalent to an -dimensional first-order system (as described in reduction to a first-order system), but not necessarily vice versa.

First order

The first-order autonomous equation is separable, so it can be solved by rearranging it into the integral form

Second order

The second-order autonomous equation is more difficult, but it can be solved by introducing the new variable and expressing the second derivative of via the chain rule as so that the original equation becomes which is a first order equation containing no reference to the independent variable . Solving provides as a function of . Then, recalling the definition of :

which is an implicit solution.

Special case: x″ = f(x)

The special case where is independent of

benefits from separate treatment. These types of equations are very common in classical mechanics because they are always Hamiltonian systems.

The idea is to make use of the identity

which follows from the chain rule, barring any issues due to division by zero.

By inverting both sides of a first order autonomous system, one can immediately integrate with respect to :

which is another way to view the separation of variables technique. The second derivative must be expressed as a derivative with respect to instead of :

To reemphasize: what's been accomplished is that the second derivative with respect to has been expressed as a derivative of . The original second order equation can now be integrated:

This is an implicit solution. The greatest potential problem is inability to simplify the integrals, which implies difficulty or impossibility in evaluating the integration constants.

Special case: x″ = x′ f(x)

Using the above approach, the technique can extend to the more general equation

where is some parameter not equal to two. This will work since the second derivative can be written in a form involving a power of . Rewriting the second derivative, rearranging, and expressing the left side as a derivative:

The right will carry +/− if is even. The treatment must be different if :

Higher orders

There is no analogous method for solving third- or higher-order autonomous equations. Such equations can only be solved exactly if they happen to have some other simplifying property, for instance linearity or dependence of the right side of the equation on the dependent variable only (i.e., not its derivatives). This should not be surprising, considering that nonlinear autonomous systems in three dimensions can produce truly chaotic behavior such as the Lorenz attractor and the Rössler attractor.

Likewise, general non-autonomous equations of second order are unsolvable explicitly, since these can also be chaotic, as in a periodically forced pendulum.

Multivariate case

Main article: Matrix differential equationIn , where is an -dimensional column vector dependent on .

The solution is where is an constant vector.

Finite durations

For non-linear autonomous ODEs it is possible under some conditions to develop solutions of finite duration, meaning here that from its own dynamics, the system will reach the value zero at an ending time and stay there in zero forever after. These finite-duration solutions cannot be analytical functions on the whole real line, and because they will be non-Lipschitz functions at the ending time, they don't stand uniqueness of solutions of Lipschitz differential equations.

As example, the equation:

Admits the finite duration solution:

See also

References

- Egwald Mathematics - Linear Algebra: Systems of Linear Differential Equations: Linear Stability Analysis Accessed 10 October 2019.

- Boyce, William E.; Richard C. DiPrima (2005). Elementary Differential Equations and Boundary Volume Problems (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 133. ISBN 0-471-43338-1.

- "Second order autonomous equation" (PDF). Eqworld. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- Third order autonomous equation at eqworld.

- Fourth order autonomous equation at eqworld.

- Blanchard; Devaney; Hall (2005). Differential Equations. Brooks/Cole Publishing Co. pp. 540–543. ISBN 0-495-01265-3.

- "Method of Matrix Exponential". Math24. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- Vardia T. Haimo (1985). "Finite Time Differential Equations". 1985 24th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. pp. 1729–1733. doi:10.1109/CDC.1985.268832. S2CID 45426376.

| Differential equations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification |

| ||||||

| Solutions | |||||||

| Examples | |||||||

| Mathematicians | |||||||

as stable or unstable according to their features. Stability generally increases to the left of the diagram. Some sink, source or node are

as stable or unstable according to their features. Stability generally increases to the left of the diagram. Some sink, source or node are  where x takes values in n-dimensional

where x takes values in n-dimensional  in which the law governing the evolution of the system does not depend solely on the system's current state but also the parameter t, again often interpreted as time; such systems are by definition not autonomous.

in which the law governing the evolution of the system does not depend solely on the system's current state but also the parameter t, again often interpreted as time; such systems are by definition not autonomous.

be a unique solution of the

be a unique solution of the  Then

Then  solves

solves

Denoting

Denoting  gets

gets  and

and  , thus

, thus

For the initial condition, the verification is trivial,

For the initial condition, the verification is trivial,

is autonomous, since the independent variable (

is autonomous, since the independent variable ( ) does not explicitly appear in the equation.

To plot the

) does not explicitly appear in the equation.

To plot the  is

is  for any shift

for any shift  .

.

and

and  , and a third solution involving an unknown constant

, and a third solution involving an unknown constant  ,

,

is equivalent to an

is equivalent to an  is

is

is more difficult, but it can be solved by introducing the new variable

is more difficult, but it can be solved by introducing the new variable

and expressing the

and expressing the  so that the original equation becomes

so that the original equation becomes

which is a first order equation containing no reference to the independent variable

which is a first order equation containing no reference to the independent variable  . Solving provides

. Solving provides  as a function of

as a function of

is independent of

is independent of

:

:

, where

, where  is an

is an  where

where  is an

is an  constant vector.

constant vector.