| Empire State Building | |

|---|---|

Empire State Building illuminated in 2021 Empire State Building illuminated in 2021 | |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1931 to 1970 | |

| Preceded by | Chrysler Building |

| Surpassed by | World Trade Center |

| General information | |

| Type | Office building; observation decks |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| Location | 350 Fifth Avenue Manhattan, New York, 10118 U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°44′54″N 73°59′8″W / 40.74833°N 73.98556°W / 40.74833; -73.98556 |

| Construction started | March 17, 1930; 94 years ago (1930-03-17) |

| Topped-out | September 19, 1930; 94 years ago (1930-09-19) |

| Completed | April 11, 1931; 93 years ago (1931-04-11) |

| Opened | May 1, 1931; 93 years ago (May 1, 1931) |

| Cost | $40,948,900 (equivalent to $661 million in 2023) |

| Owner | Empire State Realty Trust |

| Height | |

| Tip | 1,454 ft (443.2 m) |

| Antenna spire | 204 ft (62.2 m) |

| Roof | 1,250 ft (381.0 m) |

| Top floor | 1,224 ft (373.1 m) |

| Observatory | 80th, 86th, and 102nd (top) floors |

| Dimensions | |

| Other dimensions | 424 ft (129.2 m) east–west; 187 ft (57.0 m) north–south |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 102 |

| Floor area | 2,248,355 sq ft (208,879 m) |

| Lifts/elevators | 73 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Shreve, Lamb and Harmon |

| Developer | Empire State Inc., including John J. Raskob and Al Smith |

| Structural engineer | Homer Gage Balcom |

| Main contractor | Starrett Brothers and Eken |

| Website | |

| esbnyc | |

| U.S. National Historic Landmark | |

| Designated | June 24, 1986 |

| Reference no. | 82001192 |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| Designated | November 17, 1982 |

| Reference no. | 82001192 |

| New York State Register of Historic Places | |

| Designated | September 27, 1982 |

| Reference no. | 06101.001691 |

| New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | May 19, 1981 |

| Reference no. | 2000 |

| Designated entity | Facade |

| New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | May 19, 1981 |

| Reference no. | 2001 |

| Designated entity | Interior: Lobby |

| References | |

| I. "Empire State Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. | |

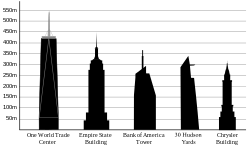

The Empire State Building is a 102-story Art Deco skyscraper in the Midtown South neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. The building was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and built from 1930 to 1931. Its name is derived from "Empire State", the nickname of the state of New York. The building has a roof height of 1,250 feet (380 m) and stands a total of 1,454 feet (443.2 m) tall, including its antenna. The Empire State Building was the world's tallest building until the first tower of the World Trade Center was topped out in 1970; following the September 11 attacks in 2001, the Empire State Building was New York City's tallest building until it was surpassed in 2012 by One World Trade Center. As of 2024, the building is the seventh-tallest building in New York City, the ninth-tallest completed skyscraper in the United States, and the 57th-tallest completed skyscraper in the world.

The site of the Empire State Building, on the west side of Fifth Avenue between West 33rd and 34th Streets, was developed in 1893 as the Waldorf–Astoria Hotel. In 1929, Empire State Inc. acquired the site and devised plans for a skyscraper there. The design for the Empire State Building was changed fifteen times until it was ensured to be the world's tallest building. Construction started on March 17, 1930, and the building opened thirteen and a half months afterward on May 1, 1931. Despite favorable publicity related to the building's construction, because of the Great Depression and World War II, its owners did not make a profit until the early 1950s.

The building's Art Deco architecture, height, and observation decks have made it a popular attraction. Around four million tourists from around the world annually visit the building's 86th- and 102nd-floor observatories; an additional indoor observatory on the 80th floor opened in 2019. The Empire State Building is an international cultural icon: it has been featured in more than 250 television series and films since the film King Kong was released in 1933. The building's size has been used as a standard of reference to describe the height and length of other structures. A symbol of New York City, the building has been named as one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World by the American Society of Civil Engineers. It was ranked first on the American Institute of Architects' List of America's Favorite Architecture in 2007. Additionally, the Empire State Building and its ground-floor interior were designated city landmarks by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1980, and were added to the National Register of Historic Places as a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

Site

The Empire State Building is located on the west side of Fifth Avenue, between 33rd Street to the south and 34th Street to the north, in the Midtown South neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Tenants enter the building through the Art Deco lobby located at 350 Fifth Avenue. Visitors to the observatories use an entrance at 20 West 34th Street; prior to August 2018, visitors entered through the Fifth Avenue lobby. Although physically located in South Midtown, a mixed residential and commercial area, the building is so large that it was assigned its own ZIP Code, 10118; as of 2012, it is one of 43 buildings in New York City that have their own ZIP codes.

The areas surrounding the Empire State Building are home to other major points of interest, including Macy's at Herald Square on Sixth Avenue and 34th Street, and Koreatown on 32nd Street between Madison and Sixth avenues. To the east of the Empire State Building is Murray Hill, a neighborhood with a mix of residential, commercial, and entertainment activity. The block directly to the northeast contains the B. Altman and Company Building, which houses the City University of New York's Graduate Center. The nearest New York City Subway stations are 34th Street–Herald Square, one block west, and 33rd Street at Park Avenue, two blocks east; there is also a PATH station at 33rd Street and Sixth Avenue.

Architecture

The Empire State Building was designed by Shreve, Lamb and Harmon in the Art Deco style. The Empire State Building is 1,250 ft (381 m) tall to its 102nd floor, or 1,453 feet 8+9⁄16 inches (443.092 m) including its 203-foot (61.9 m) pinnacle. It was the first building in the world to be more than 100 stories tall, though only the lowest 86 stories are usable. The first through 85th floors contain 2.158 million square feet (200,500 m) of commercial and office space, while the 86th floor contains an observatory. The remaining 16 stories are part of the spire, which is capped by an observatory on the 102nd floor; the spire does not contain any intermediate levels and is used mostly for mechanical purposes. Atop the 102nd story is the 203 ft (61.9 m) pinnacle, much of which is covered by broadcast antennas, and surmounted with a lightning rod.

Form

The Empire State Building has a symmetrical massing because of its large lot and relatively short base. Its articulation consists of three horizontal sections—a base, shaft, and capital—similar to the components of a column. The five-story base occupies the entire lot, while the 81-story shaft above it is set back sharply from the base. The setback above the 5th story is 60 feet (18 m) deep on all sides. There are smaller setbacks on the upper stories, allowing sunlight to illuminate the interiors of the top floors while also positioning these floors away from the noisy streets below. The setbacks are located at the 21st, 25th, 30th, 72nd, 81st, and 85th stories. The setbacks correspond to the tops of elevator shafts, allowing interior spaces to be at most 28 feet (8.5 m) deep (see: § Interior).

The setbacks were mandated by the 1916 Zoning Resolution, which was intended to allow sunlight to reach the streets as well. Normally, a building of the Empire State's dimensions would be permitted to build up to 12 stories on the Fifth Avenue side, and up to 17 stories on the 33rd Street and 34th Street sides, before it would have to utilize setbacks. However, with the largest setback being located above the base, the tower stories could contain a uniform shape. According to architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern, the building's form contrasted with the nearly contemporary, similarly designed 500 Fifth Avenue eight blocks north, which had an asymmetrical massing on a smaller lot.

Facade

The Empire State Building's Art Deco design is typical of pre–World War II architecture in New York City. The facade is clad in Indiana limestone panels made by the Indiana Limestone Company and sourced from a quarry in south-central Indiana; the panels give the building its signature blonde color. According to official fact sheets, the facade uses 200,000 cubic feet (5,700 m) of limestone and granite, ten million bricks, and 730 short tons (650 long tons) of aluminum and stainless steel. The building also contains 6,514 windows. The decorative features on the facade are largely geometric, in contrast with earlier buildings, whose decorations often were intended to represent a specific narrative.

The main entrance, composed of three sets of metal doors, is at the center of the facade's Fifth Avenue elevation, flanked by molded piers that are topped with eagles. Above the main entrance is a transom, a triple-height transom window with geometric patterns, and the golden letters "Empire State" above the fifth-floor windows. There are two entrances each on 33rd and 34th streets, with modernistic, stainless steel canopies projecting from the entrances on 33rd and 34th streets there. Above the secondary entrances are triple windows, less elaborate in design than those on Fifth Avenue.

The storefronts on the first floor contain aluminum-framed doors and windows within a black granite cladding. The second through fourth stories consist of windows alternating with wide stone piers and narrower stone mullions. The fifth story contains windows alternating with wide and narrow mullions, and is topped by a horizontal stone sill.

The facade of the tower stories is split into several vertical bays on each side, with windows projecting slightly from the limestone cladding. The bays are arranged into sets of one, two, or three windows on each floor. The bays are separated by alternating narrow and wide piers, the inclusion of which may have been influenced by the design of the contemporary Daily News Building. The windows in each bay are separated by vertical nickel-chrome steel mullions and connected by horizontal aluminum spandrels between each floor. The windows are placed within stainless-steel frames, which saved money by eliminating the need to apply a stone finish around the windows. In addition, the use of aluminum spandrels obviated the need for cross-bonding, which would have been required if stone had been used instead.

Lights

The building was originally equipped with white searchlights at the top. They were first used in November 1932 when they lit up to signal Roosevelt's victory over Hoover in the presidential election of that year. These were later swapped for four "Freedom Lights" in 1956. In February 1964, flood lights were added on the 72nd floor to illuminate the top of the building at night so that the building could be seen from the World Fair later that year. The lights were shut off from November 1973 to July 1974 because of the energy crisis at the time. In 1976, the businessman Douglas Leigh suggested that Wien and Helmsley install 204 metal-halide lights, which were four times as bright as the 1,000 incandescent lights they were to replace. New red, white, and blue metal-halide lights were installed in time for the country's bicentennial that July. After the bicentennial, Helmsley retained the new lights due to the reduced maintenance cost, about $116 a year.

Since October 12, 1977, the spire has been lit in colors chosen to match seasonal events and holidays. Organizations are allowed to make requests through the building's website. The building is also lit in the colors of New York-based sports teams on nights when they host games: for example, orange, blue, and white for the New York Knicks; red, white, and blue for the New York Rangers. The spire can also be lit to commemorate events including disasters, anniversaries, or deaths, as well as for celebrations such as Pride and Halloween. In 1998, the building was lit in blue after the death of singer Frank Sinatra, who was nicknamed "Ol' Blue Eyes".

The structure was lit in red, white, and blue for several months after the September 11 attacks in 2001. On January 13, 2012, the building was lit in red, orange, and yellow to honor the 60th anniversary of the NBC program The Today Show. After retired basketball player Kobe Bryant's January 2020 death, the building was lit in purple and gold, signifying the colors of his former team, the Los Angeles Lakers. The evening after iconic actor James Earl Jones died, September 9, 2024, the building was lit up to look like Jones's iconic Darth Vader villain from "Star Wars."

In addition to lightings, the Empire State Building is able to do immersive visual projections on the building's exterior. It partnered with Netflix in May 2022 to celebrate the return of Stranger Things fourth season by projecting the Upside Down onto the Empire State Building.

In 2012, the building's four hundred metal halide lamps and floodlights were replaced with 1,200 LED fixtures, increasing the available colors from nine to over 16 million. The computer-controlled system allows the building to be illuminated in ways that were unable to be done previously with plastic gels. For instance, CNN used the top of the Empire State Building as a scoreboard during the 2012 United States presidential election, using red and blue lights to represent Republican and Democratic electoral votes respectively. Also, on November 26, 2012, the building had its first synchronized light show, using music from recording artist Alicia Keys. Artists such as Eminem and OneRepublic have been featured in later shows, including the building's annual Holiday Music-to-Lights Show. The building's owners adhere to strict standards in using the lights; for instance, they do not use the lights to play advertisements.

-

Lights representing the Democratic and Republican parties as results are tabulated in the 2012 presidential election

Lights representing the Democratic and Republican parties as results are tabulated in the 2012 presidential election

-

The Empire State Building is bathed annually in rainbow-colored lighting during the Pride Month of June, evoking the international LGBT icon, as seen in this 2015 image.

The Empire State Building is bathed annually in rainbow-colored lighting during the Pride Month of June, evoking the international LGBT icon, as seen in this 2015 image.

Interior

According to official fact sheets, the Empire State Building weighs 365,000 short tons (331,122 t) and has an internal volume of 37 million cubic feet (1,000,000 m). The interior required 1,172 miles (1,886 km) of elevator cable and 2 million feet (609,600 m) of electrical wires. It has a total floor area of 2,768,591 sq ft (257,211 m), and each of the floors in the base cover 2 acres (1 ha). This gives the building capacity for 20,000 tenants and 15,000 visitors.

The riveted steel frame of the building was originally designed to handle all of the building's gravitational stresses and wind loads. The amount of material used in the building's construction resulted in a very stiff structure when compared to other skyscrapers, with a structural stiffness of 42 pounds per square foot (2.0 kPa) versus the Willis Tower's 33 pounds per square foot (1.6 kPa) and the John Hancock Center's 26 pounds per square foot (1.2 kPa). A December 1930 feature in Popular Mechanics estimated that a building with the Empire State's dimensions would still stand even if hit with an impact of 50 short tons (45 long tons).

Utilities are grouped in a central shaft. On the 6th through 86th stories, the central shaft is surrounded by a main corridor on all four sides. Per the final specifications of the building, the corridor is surrounded in turn by office space 28 feet (8.5 m) deep, maximizing office space at a time before air conditioning became commonplace. Each of the floors has 210 structural columns that pass through it, which provide structural stability but limits the amount of open space on these floors. The relative dearth of stone in the Empire State Building allows for more space overall, with a 1:200 stone-to-building ratio compared to a 1:50 ratio in similar buildings.

Lobby

The original main lobby is accessed from Fifth Avenue, on the building's east side, and is the only place in the building where the design contains narrative motifs. It contains an entrance with one set of double doors between a pair of revolving doors. At the top of each doorway is a bronze motif depicting one of three "crafts or industries" used in the building's construction—Electricity, Masonry, and Heating. The three-story-high space runs parallel to 33rd and 34th Streets. The lobby contains two tiers of marble: a wainscoting of darker marble, topped by lighter marble. There is a pattern of zigzagging terrazzo tiles on the lobby floor, which leads from east to west. To the north and south are storefronts, which are flanked by tubes of dark rounded marble and topped by a vertical band of grooves set into the marble. Until the 1960s, there was a Longchamps restaurant next to the lobby, with six oval murals designed by Winold Reiss; these murals were placed in storage when the Longchamps closed.

The western ends of the north and south walls include escalators to a mezzanine level. At the west end of the lobby, behind the security desk, is an aluminum relief of the skyscraper as it was originally built (without the antenna). The relief, which was intended to provide a welcoming effect, contains an embossed outline of the building, with rays radiating from the spire and the sun behind it. In the background is a state map of New York with the building's location marked by a "medallion" in the very southeast portion of the outline. A compass is depicted in the bottom right and a plaque to the building's major developers is on the bottom left. A scale model of the building was also placed south of the security desk.

The plaque at the western end of the lobby is on the eastern interior wall of a one-story-tall rectangular-shaped corridor that surrounds the banks of escalators, with a similar design to the lobby. The rectangular-shaped corridor actually consists of two long hallways on the northern and southern sides of the rectangle, as well as a shorter hallway on the eastern side and another long hallway on the western side. At both ends of the northern and southern corridors, there is a bank of four low-rise elevators in between the corridors. The western side of the rectangular elevator-bank corridor extends north to the 34th Street entrance and south to the 33rd Street entrance. It borders three large storefronts and leads to escalators (originally stairs), which go both to the second floor and to the basement. Going from west to east, there are secondary entrances to 34th and 33rd Streets from the northern and southern corridors, respectively. The side entrances from 33rd and 34th Street lead to two-story-high corridors around the elevator core, crossed by stainless steel-and-glass-enclosed bridges at the mezzanine floor.

Until the 1960s, an Art Deco mural, inspired by both the sky and the Machine Age, was installed in the lobby ceilings. Subsequent damage to these murals, designed by artist Leif Neandross, resulted in reproductions being installed. Renovations to the lobby in 2009, such as replacing the clock over the information desk in the Fifth Avenue lobby with an anemometer and installing two chandeliers intended to be part of the building when it originally opened, revived much of its original grandeur. The north corridor contained eight illuminated panels created in 1963 by Roy Sparkia and Renée Nemorov, in time for the 1964 World's Fair, depicting the building as the Eighth Wonder of the World alongside the traditional seven. The building's owners installed a series of paintings by the New York artist Kysa Johnson in the concourse level. Johnson later filed a federal lawsuit, in January 2014, under the Visual Artists Rights Act alleging the negligent destruction of the paintings and damage to her reputation as an artist. As part of the building's 2010 renovation, Denise Amses commissioned a work consisting of 15,000 stars and 5,000 circles, superimposed on a 13-by-5-foot (4.0 by 1.5 m) etched-glass installation, in the lobby.

Elevators

The Empire State Building has 73 elevators in all, including service elevators. Its original 64 elevators, built by the Otis Elevator Company, in a central core and are of varying heights, with the longest of these elevators reaching from the lobby to the 80th floor. As originally built, there were four "express" elevators that connected the lobby, 80th floor, and several landings in between; the other 60 "local" elevators connected the landings with the floors above these intermediate landings. Of the 64 total elevators, 58 were for passenger use (comprising the four express elevators and 54 local elevators), and eight were for freight deliveries. The elevators were designed to move at 1,200 feet per minute (366 m/min). At the time of the skyscraper's construction, their practical speed was limited to 700 feet per minute (213 m/min) per city law, but this limit was removed shortly after the building opened.

Additional elevators connect the 80th floor to the six floors above it, as the six extra floors were built after the original 80 stories were approved. The elevators were mechanically operated until 2011, when they were replaced with automatic elevators during the $550 million renovation of the building. An additional elevator connects the 86th and 102nd floor observatories, which allows visitors access the 102nd floor observatory after having their tickets scanned. It also allows employees to access the mechanical floors located between the 87th and 101st floors.

Observation decks

The 80th, 86th, and 102nd floors contain observatories. The latter two observatories saw a combined average of four million visitors per year in 2010. Since opening, the observatories have been more popular than similar observatories at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the Chrysler Building, the first One World Trade Center, or the Woolworth Building, despite being more expensive. There are variable charges to enter the observatories; one ticket allows visitors to go as high as the 86th floor, and there is an additional charge to visit the 102nd floor. Other ticket options for visitors include scheduled access to view the sunrise from the observatory, a "premium" guided tour with VIP access, and the "AM/PM" package which allows for two visits in the same day.

Interior and exterior observation decks at the 86th floor

Interior and exterior observation decks at the 86th floor

The 86th floor observatory contains both an enclosed viewing gallery and an open-air outdoor viewing area, allowing for it to remain open 365 days a year regardless of the weather. The 102nd floor observatory is completely enclosed and much smaller in size. The 102nd floor observatory was closed to the public from the late 1990s to 2005 due to limited viewing capacity and long lines. The observation decks were redesigned in mid-1979. The 102nd floor was again redesigned in a project that was completed in 2019, allowing the windows to be extended from floor to ceiling and widening the space in the observatory overall. An observatory on the 80th floor, opened in 2019, includes various exhibits as well as a mural of the skyline drawn by British artist Stephen Wiltshire. An interactive multimedia museum, with multiple hands-on exhibitions about the building's history, was added during this project. The design of the 10,000 sq ft (930 m) Observatory Experience was inspired by the plans and designs of the original Empire State Building.

According to a 2010 report by Concierge.com, the five lines to enter the observation decks are "as legendary as the building itself". Concierge.com stated that there were five lines: the sidewalk line, the lobby elevator line, the ticket purchase line, the second elevator line, and the line to get off the elevator and onto the observation deck. In 2016, New York City's official tourism website made note of only three lines: the security check line, the ticket purchase line, and the second elevator line. Following renovations completed in 2019, designed to streamline queuing and reduce wait times, guests enter from a single entrance on 34th Street, where they make their way through 10,000-square-foot (930 m) exhibits on their way up to the observatories. Guests were offered a variety of ticket packages, including a package that enables them to skip the lines throughout the duration of their stay. The Empire State Building garners significant revenue from ticket sales for its observation decks, making more money from ticket sales than it does from renting office space during some years.

A 360° panoramic view of New York City from the 86th-floor observation deck in spring 2005. East River is to the left, Hudson River to the right, south is near center.

A 360° panoramic view of New York City from the 86th-floor observation deck in spring 2005. East River is to the left, Hudson River to the right, south is near center.

New York Skyride

In early 1994, a motion simulator attraction was built on the 2nd floor, as a complement to the observation deck. The original cinematic presentation lasted approximately 25 minutes, while the simulation was about eight minutes. The ride had two incarnations. The original version, which ran from 1994 until around 2002, featured James Doohan, Star Trek's Scotty, as the airplane's pilot who humorously tried to keep the flight under control during a storm. After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the ride was closed. An updated version debuted in mid-2002, featuring actor Kevin Bacon as the pilot, with the new flight also going haywire. This new version served a more informative goal, as opposed to the old version's main purpose of entertainment, and contained details about the 9/11 attacks. The simulator received mixed reviews, with assessments of the ride ranging from "great" to "satisfactory" to "corny".

Spire

Above the 102nd floor

The final stage of the building was the installation of a hollow mast, a 158-foot (48 m) steel shaft fitted with elevators and utilities, above the 86th floor. The spire of the Empire State Building was originally intended to serve as a mooring mast for zeppelins and other airships, although the plan was abandoned after high winds made that impossible. At the top would be a conical roof and the 102nd-floor docking station. Inside, the elevators would ascend 167 feet (51 m) from the 86th-floor ticket offices to a 33-foot-wide (10 m) 101st-floor waiting room. From there, stairs would lead to the 102nd floor, where passengers would enter the airships. The airships would have been moored to the spire at the equivalent of the building's 106th floor.

As constructed, the mast contains four rectangular tiers topped by a cylindrical shaft with a conical pinnacle. On the 102nd floor (formerly the 101st floor), there is a door with stairs ascending to the 103rd floor (formerly the 102nd). This was built as a disembarkation floor for airships tethered to the building's spire, and has a circular balcony outside. It is now an access point to reach the spire for maintenance. The room now contains electrical equipment, but celebrities and dignitaries may also be given permission to take pictures there. A set of stairs and a ladder ascend to the spire and are used by maintenance workers. The mast's 480 windows were all replaced in 2015. The mast serves as the base of the building's broadcasting antenna.

Inflatable objects have sometimes been mounted to the spire for promotional purposes. For example, a King Kong balloon was attached to the spire in 1983 to mark the 50th anniversary of the character's introduction, and an inflatable dragon was placed on the spire in 2024 to promote the TV series House of Dragon.

Broadcast stations

Broadcasting began at the Empire State Building on December 22, 1931, when NBC and RCA began transmitting experimental television broadcasts from a small antenna erected atop the mast, with two separate transmitters for the visual and audio data. They leased the 85th floor and built a laboratory there. In 1934, RCA was joined by Edwin Howard Armstrong in a cooperative venture to test his FM system from the building's antenna. This setup, which entailed the installation of the world's first FM transmitter, continued only until October of the next year due to disputes between RCA and Armstrong. Specifically, NBC wanted to install more TV equipment in the room where Armstrong's transmitter was located.

After some time, the 85th floor became home to RCA's New York television operations initially as experimental station W2XBS channel 1 then, from 1941, as commercial station WNBT channel 1 (now WNBC channel 4). NBC's FM station, W2XDG, began transmitting from the antenna in 1940. NBC retained exclusive use of the top of the building until 1950 when the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ordered the exclusive deal be terminated. The FCC directive was based on consumer complaints that a common location was necessary for the seven extant New York-area television stations to transmit from so that receiving antennas would not have to be constantly adjusted. Other television broadcasters would later join RCA at the building on the 81st through 83rd floors, often along with sister FM stations. Construction of a dedicated broadcast tower began on July 27, 1950, with TV, and FM, transmissions starting in 1951. The 200-foot (61 m) broadcast tower was completed in 1953. From 1951, six broadcasters agreed to pay a combined $600,000 per year for the use of the antenna. In 1965, a separate set of FM antennae was constructed ringing the 103rd floor observation area to act as a master antenna.

The placement of the stations in the Empire State Building became a major issue with the construction of the World Trade Center's Twin Towers in the late 1960s, and early 1970s. The greater height of the Twin Towers would reflect radio waves broadcast from the Empire State Building, eventually resulting in some broadcasters relocating to the newer towers instead of suing the developer, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Even though the nine stations who were broadcasting from the Empire State Building were leasing their broadcast space until 1984, most of these stations moved to the World Trade Center as soon as it was completed in 1971. The broadcasters obtained a court order stipulating that the Port Authority had to build a mast and transmission equipment in the North Tower, as well as pay the broadcasters' leases in the Empire State Building until 1984. Only a few broadcasters renewed their leases in the Empire State Building.

The September 11 attacks destroyed the World Trade Center and the broadcast centers atop it, leaving most of the city's stations without a transmitter for ten days until the Armstrong Tower in Alpine, New Jersey, was re-activated temporarily. By October 2001, nearly all of the city's commercial broadcast stations (both television and FM radio) were again transmitting from the top of the Empire State Building. In a report that Congress commissioned about the transition from analog television to digital television, it was stated that the placement of broadcast stations in the Empire State Building was considered "problematic" due to interference from nearby buildings. In comparison, the congressional report stated that the former Twin Towers had very few buildings of comparable height nearby thus signals suffered little interference. In 2003, a few FM stations were relocated to the nearby Condé Nast Building to reduce the number of broadcast stations using the Empire State Building. Eleven television stations and twenty-two FM stations had signed 15-year leases in the building by May 2003. It was expected that a taller broadcast tower in Bayonne, New Jersey, or Governors Island, would be built in the meantime with the Empire State Building being used as a "backup" since signal transmissions from the building were generally of poorer quality. Following the construction of One World Trade Center in the late 2000s and early 2010s, some TV stations began moving their transmitting facilities there.

As of 2021, the Empire State Building is home to the following stations:

- Television: WABC-7, WPIX-11, WXTV-41 Paterson, and WFUT-68 Newark

- FM: WINS-92.3, WPAT-93.1 Paterson, WNYC-93.9, WPLJ-95.5, WXNY-96.3, WQHT-97.1, WSKQ-97.9, WEPN-98.7, WHTZ-100.3 Newark, WCBS-101.1, WFAN-101.9, WNEW-FM-102.7, WKTU-103.5 Lake Success, WAXQ-104.3, WWPR-105.1, WQXR-105.9 Newark, WLTW-106.7, and WBLS-107.5

- NOAA Weather Radio station KWO35 broadcasts at a frequency of 162.550 MHz from the National Weather Service in Upton, New York.

History

The site was previously owned by John Jacob Astor of the prominent Astor family, who had owned the site since the mid-1820s. In 1893, John Jacob Astor Sr.'s grandson William Waldorf Astor opened the Waldorf Hotel on the site. Four years later, his cousin, John Jacob Astor IV, opened the 16-story Astoria Hotel on an adjacent site. The two portions of the Waldorf–Astoria hotel had 1,300 bedrooms, making it the largest hotel in the world at the time. After the death of its founding proprietor, George Boldt, in early 1918, the hotel lease was purchased by Thomas Coleman du Pont. By the 1920s, the old Waldorf–Astoria was becoming dated and the elegant social life of New York had moved much farther north. Additionally, many stores had opened on Fifth Avenue north of 34th Street. The Astor family decided to build a replacement hotel on Park Avenue and sold the hotel to Bethlehem Engineering Corporation in 1928 for $14–16 million. The hotel closed shortly thereafter on May 3, 1929.

Planning

Early plans

Bethlehem Engineering Corporation originally intended to build a 25-story office building on the Waldorf–Astoria site. The company's president, Floyd De L. Brown, paid $100,000 of the $1 million down payment required to start construction on the building, with the promise that the difference would be paid later. Brown borrowed $900,000 from a bank but defaulted on the loan.

After Brown was unable to secure additional funding, the land was resold to Empire State Inc., a group of wealthy investors that included Louis G. Kaufman, Ellis P. Earle, John J. Raskob, Coleman du Pont, and Pierre S. du Pont. The name came from the state nickname for New York. Alfred E. Smith, a former Governor of New York and U.S. presidential candidate whose 1928 campaign had been managed by Raskob, was appointed head of the company. The group also purchased nearby land so they would have the 2 acres (1 ha) needed for the base, with the combined plot measuring 425 feet (130 m) wide by 200 feet (61 m) long. The Empire State Inc. consortium was announced to the public in August 1929. Concurrently, Smith announced the construction of an 80-story building on the site, to be taller than any other buildings in existence.

Empire State Inc. contracted William F. Lamb, of architectural firm Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, to create the building design. Lamb produced the initial building design using the firm's earlier designs for the Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, as the basis. He had also been inspired by Raymond Hood's design for the Daily News Building, which was being constructed at the same time. Concurrently, Lamb's partner Richmond Shreve created "bug diagrams" of the project requirements. The 1916 Zoning Act forced Lamb to design a structure that incorporated setbacks resulting in the lower floors being larger than the upper floors. Consequently, the building was conceived from the top down, giving it a pencil-like shape. The plans were devised within a budget of $50 million and a stipulation that the building be ready for occupancy within 18 months of the start of construction. Design drawings and construction were concurrent. Steel drawings were completed in mid-January 1930, when foundations were underway.

Design changes

The original plan of the building was 50 stories, but was later increased to 60 and then 80 stories. Height restrictions were placed on nearby buildings to ensure that the top fifty floors of the planned 80-story, 1,000-foot-tall (300 m) building would have unobstructed views of the city. The New York Times lauded the site's proximity to mass transit, with the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit's 34th Street station and the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad's 33rd Street terminal one block away, as well as Penn Station two blocks away and Grand Central Terminal nine blocks away at its closest. It also praised the 3,000,000 square feet (280,000 m) of proposed floor space near "one of the busiest sections in the world". The Empire State Building was to be a typical office building, but Raskob intended to build it "better and in a bigger way", according to architectural writer Donald J. Reynolds.

While plans for the Empire State Building were being finalized, an intense competition in New York for the title of "world's tallest building" was underway. 40 Wall Street (then the Bank of Manhattan Building) and the Chrysler Building in Manhattan both vied for this distinction and were already under construction when work began on the Empire State Building. The "Race into the Sky", as popular media called it at the time, was representative of the country's optimism in the 1920s, fueled by the building boom in major cities. The race was defined by at least five other proposals, although only the Empire State Building would survive the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The 40 Wall Street tower was revised, in April 1929, from 840 feet (260 m) to 925 feet (282 m) making it the world's tallest. The Chrysler Building added its 185-foot (56 m) steel tip to its roof in October 1929, thus bringing it to a height of 1,046 feet (319 m) and greatly exceeding the height of 40 Wall Street. The Chrysler Building's developer, Walter Chrysler, realized that his tower's height would exceed the Empire State Building's as well, having instructed his architect, William Van Alen, to change the Chrysler's original roof from a stubby Romanesque dome to a narrow steel spire. Raskob, wishing to have the Empire State Building be the world's tallest, reviewed the plans and had five floors added as well as a spire; however, the new floors would need to be set back because of projected wind pressure on the extension. On November 18, 1929, Smith acquired a lot at 27–31 West 33rd Street, adding 75 feet (23 m) to the width of the proposed office building's site. Two days later, Smith announced the updated plans for the skyscraper. The plans included an observation deck on the 86th-floor roof at a height of 1,050 feet (320 m), higher than the Chrysler's 71st-floor observation deck.

The 1,050-foot Empire State Building would only be 4 feet (1.2 m) taller than the Chrysler Building, and Raskob was afraid that Chrysler might try to "pull a trick like hiding a rod in the spire and then sticking it up at the last minute." The plans were revised one last time in December 1929, to include a 16-story, 200-foot (61 m) metal "crown" and an additional 222-foot (68 m) mooring mast intended for dirigibles. The roof height was now 1,250 feet (380 m), making it the tallest building in the world by far, even without the antenna. The addition of the dirigible station meant that another floor, the 86th, would have to be built below the crown; however, unlike the Chrysler's spire, the Empire State's mast would serve a practical purpose. A revised plan was announced to the public in late December 1929, just before the start of construction. The final plan was sketched within two hours, the night before the plan was supposed to be presented to the site's owners in January 1930. The New York Times reported that the spire was facing some "technical problems", but they were "no greater than might be expected under such a novel plan." By this time the blueprints for the building had gone through up to fifteen versions before they were approved. Lamb described the other specifications he was given for the final, approved plan:

The program was short enough—a fixed budget, no space more than 28 feet from window to corridor, as many stories of such space as possible, an exterior of limestone, and completion date of , 1931, which meant a year and six months from the beginning of sketches.

Construction

The contractors were Starrett Brothers and Eken, which were composed of Paul and William A. Starrett and Andrew J. Eken. The project was financed primarily by Raskob and Pierre du Pont, while James Farley's General Builders Supply Corporation supplied the building materials. John W. Bowser was the construction superintendent of the project, and the structural engineer of the building was Homer G. Balcom. The tight completion schedule necessitated the commencement of construction even though the design had yet to be finalized.

Hotel demolition

Demolition of the old Waldorf–Astoria began on October 1, 1929. Stripping the building down was an arduous process, as the hotel had been constructed using more rigid material than earlier buildings had been. Furthermore, the old hotel's granite, wood chips, and "'precious' metals such as lead, brass, and zinc" were not in high demand, resulting in issues with disposal. Most of the wood was deposited into a woodpile on nearby 30th Street or was burned in a swamp elsewhere. Much of the other materials that made up the old hotel, including the granite and bronze, were dumped into the Atlantic Ocean near Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

By the time the hotel's demolition started, Raskob had secured the required funding for the construction of the building. The plan was to start construction later that year but, on October 24, the New York Stock Exchange experienced the major and sudden Wall Street Crash, marking the beginning of the decade-long Great Depression. Despite the economic downturn, Raskob refused to cancel the project because of the progress that had been made up to that point. Neither Raskob, who had ceased speculation in the stock market the previous year, nor Smith, who had no stock investments, suffered financially in the crash. However, most of the investors were affected and as a result, in December 1929, Empire State Inc. obtained a $27.5 million loan from Metropolitan Life Insurance Company so construction could begin. The stock market crash resulted in no demand for new office space; Raskob and Smith nonetheless started construction, as canceling the project would have resulted in greater losses for the investors.

Steel structure

A structural steel contract was awarded on January 12, 1930, with excavation of the site beginning ten days later on January 22, before the old hotel had been completely demolished. Two twelve-hour shifts, consisting of 300 men each, worked continuously to dig the 55-foot (17 m) deep foundation. Small pier holes were sunk into the ground to house the concrete footings that would support the steelwork. Excavation was nearly complete by early March, and construction on the building itself started on March 17, with the builders placing the first steel columns on the completed footings before the rest of the footings had been finished. Around this time, Lamb held a press conference on the building plans. He described the reflective steel panels parallel to the windows, the large-block Indiana Limestone facade that was slightly more expensive than smaller bricks, and the building's vertical lines. Four colossal columns, intended for installation in the center of the building site, were delivered; they would support a combined 10,000,000 pounds (4,500,000 kg) when the building was finished.

The structural steel was pre-ordered and pre-fabricated in anticipation of a revision to the city's building code that would have allowed the Empire State Building's structural steel to carry 18,000 pounds per square inch (120,000 kPa), up from 16,000 pounds per square inch (110,000 kPa), thus reducing the amount of steel needed for the building. Although the 18,000-psi regulation had been safely enacted in other cities, Mayor Jimmy Walker did not sign the new codes into law until March 26, 1930, just before construction was due to commence. The first steel framework was installed on April 1, 1930. From there, construction proceeded at a rapid pace; during one stretch of 10 working days, the builders erected fourteen floors. This was made possible through precise coordination of the building's planning, as well as the mass production of common materials such as windows and spandrels. On one occasion, when a supplier could not provide timely delivery of dark Hauteville marble, Starrett switched to using Rose Famosa marble from a German quarry that was purchased specifically to provide the project with sufficient marble.

The scale of the project was massive, with trucks carrying "16,000 partition tiles, 5,000 bags of cement, 450 cubic yards of sand and 300 bags of lime" arriving at the construction site every day. There were also cafes and concession stands on five of the incomplete floors so workers did not have to descend to the ground level to eat lunch. Temporary water taps were also built so workers did not waste time buying water bottles from the ground level. Additionally, carts running on a small railway system transported materials from the basement storage to elevators that brought the carts to the desired floors where they would then be distributed throughout that level using another set of tracks. The 57,480 short tons (51,320 long tons) of steel ordered for the project was the largest-ever single order of steel at the time, comprising more steel than was ordered for the Chrysler Building and 40 Wall Street combined. According to historian John Tauranac, building materials were sourced from numerous, and distant, sources with "limestone from Indiana, steel girders from Pittsburgh, cement and mortar from upper New York State, marble from Italy, France, and England, wood from northern and Pacific Coast forests, hardware from New England." The facade, too, used a variety of material—most prominently Indiana limestone but also architectural terracotta, brick, and black granite from Sweden.

By June 20, the skyscraper's supporting steel structure had risen to the 26th floor, and by July 27, half of the steel structure had been completed. Starrett Bros. and Eken endeavored to build one floor a day in order to speed up construction, achieving a pace of four and a half stories per week; prior to this, the fastest pace of construction for a building of similar height had been three and a half stories per week. While construction progressed, the final designs for the floors were being designed from the ground up (as opposed to the general design, which had been from the roof down). Some of the levels were still undergoing final approval, with several orders placed within an hour of a plan being finalized. On September 10, as steelwork was nearing completion, Smith laid the building's cornerstone during a ceremony attended by thousands. The stone contained a box with contemporary artifacts including the previous day's New York Times, a U.S. currency set containing all denominations of notes and coins minted in 1930, a history of the site and building, and photographs of the people involved in construction. The steel structure was topped out at 1,048 feet (319 m) on September 19, twelve days ahead of schedule and 23 weeks after the start of construction. Workers raised a flag atop the 86th floor to signify this milestone.

Completion and scale

Work on the building's interior and crowning mast commenced after the topping out. The mooring mast topped out on November 21, two months after the steelwork had been completed. Meanwhile, work on the walls and interior was progressing at a quick pace, with exterior walls built up to the 75th floor by the time steelwork had been built to the 95th floor. The majority of the facade was already finished by the middle of November. Because of the building's height, it was deemed infeasible to have many elevators or large elevator cabins, so the builders contracted with the Otis Elevator Company to make 66 cars that could speed at 1,200 feet per minute (366 m/min), which represented the largest-ever elevator order at the time.

In addition to the time constraint builders had, there were also space limitations because construction materials had to be delivered quickly, and trucks needed to drop off these materials without congesting traffic. This was solved by creating a temporary driveway for the trucks between 33rd and 34th Streets, and then storing the materials in the building's first floor and basements. Concrete mixers, brick hoppers, and stone hoists inside the building ensured that materials would be able to ascend quickly and without endangering or inconveniencing the public. At one point, over 200 trucks made material deliveries at the building site every day. A series of relay and erection derricks, placed on platforms erected near the building, lifted the steel from the trucks below and installed the beams at the appropriate locations. The Empire State Building was structurally completed on April 11, 1931, twelve days ahead of schedule and 410 days after construction commenced. Al Smith shot the final rivet, which was made of solid gold.

The project involved more than 3,500 workers at its peak, including 3,439 on a single day, August 14, 1930. Many of the workers were Irish and Italian immigrants, with a sizable minority of Mohawk ironworkers from the Kahnawake reserve near Montreal. According to official accounts, five workers died during the construction, although the New York Daily News gave reports of 14 deaths and a headline in the socialist magazine The New Masses spread unfounded rumors of up to 42 deaths. The Empire State Building cost $40,948,900 to build (equivalent to $661 million in 2023), including demolition of the Waldorf–Astoria. This was lower than the $60 million budgeted for construction.

Lewis Hine captured many photographs of the construction, documenting not only the work itself but also providing insight into the daily life of workers in that era. Hine's images were used extensively by the media to publish daily press releases. According to the writer Jim Rasenberger, Hine "climbed out onto the steel with the ironworkers and dangled from a derrick cable hundreds of feet above the city to capture, as no one ever had before (or has since), the dizzy work of building skyscrapers". In Rasenberger's words, Hine turned what might have been an assignment of "corporate flak" into "exhilarating art". These images were later organized into their own collection. Onlookers were enraptured by the sheer height at which the steelworkers operated. New York magazine wrote of the steelworkers: "Like little spiders they toiled, spinning a fabric of steel against the sky".

Opening and early years

The Empire State Building officially opened on May 1, 1931, forty-five days ahead of its projected opening date, and eighteen months from the start of construction. The opening was marked with an event featuring United States President Herbert Hoover, who turned on the building's lights with the ceremonial button push from Washington, D.C. Over 350 guests attended the opening ceremony, and following luncheon, at the 86th floor including Jimmy Walker, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Al Smith. An account from that day stated that the view from the luncheon was obscured by a fog, with other landmarks such as the Statue of Liberty being "lost in the mist" enveloping New York City. The Empire State Building officially opened the next day. Advertisements for the building's observatories were placed in local newspapers, while nearby hotels also capitalized on the events by releasing advertisements that lauded their proximity to the newly opened building.

According to The New York Times, builders and real estate speculators predicted that the 1,250-foot-tall (380 m) Empire State Building would be the world's tallest building "for many years", thus ending the great New York City skyscraper rivalry. At the time, most engineers agreed that it would be difficult to build a building taller than 1,200 feet (370 m), even with the hardy Manhattan bedrock as a foundation. Technically, it was believed possible to build a tower of up to 2,000 feet (610 m), but it was deemed uneconomical to do so, especially during the Great Depression. As the tallest building in the world, at that time, and the first one to exceed 100 floors, the Empire State Building became an icon of the city and, ultimately, of the nation.

In 1932, the Fifth Avenue Association gave the building its 1931 "gold medal" for architectural excellence, signifying that the Empire State had been the best-designed building on Fifth Avenue to open in 1931. A year later, on March 2, 1933, the movie King Kong was released. The movie, which depicted a large stop motion ape named Kong climbing the Empire State Building, made the still-new building into a cinematic icon.

Tenants and tourism

At the beginning of 1931, Fifth Avenue was experiencing high demand for storefront space, with only 12 of 224 stores being unoccupied. The Empire State Building, along with 500 Fifth Avenue and 608 Fifth Avenue, were expected to add a combined 11 stores. The office space was less successful, as the Empire State Building's opening had coincided with the Great Depression in the United States. In the first year, only 23 percent of the available space was rented, as compared to the early 1920s, where the average building would be 52 percent occupied upon opening and 90 percent occupied within five years. The lack of renters led New Yorkers to deride the building as the "Empty State Building" or "Smith's Folly".

The earliest tenants in the Empire State Building were large companies, banks, and garment industries. Jack Brod, one of the building's longest resident tenants, co-established the Empire Diamond Corporation with his father in the building in mid-1931 and rented space in the building until he died in 2008. Brod recalled that there were only about 20 tenants at the time of opening, including him, and that Al Smith was the only real tenant in the space above his seventh-floor offices. Generally, during the early 1930s, it was rare for more than a single office space to be rented in the building, despite Smith's and Raskob's aggressive marketing efforts in the newspapers and to anyone they knew. The building's lights were continuously left on, even in the unrented spaces, to give the impression of occupancy. This was exacerbated by competition from Rockefeller Center as well as from buildings on 42nd Street, which, when combined with the Empire State Building, resulted in surplus of office space in a slow market during the 1930s.

Aggressive marketing efforts served to reinforce the Empire State Building's status as the world's tallest. The observatory was advertised in local newspapers as well as on railroad tickets. The building became a popular tourist attraction, with one million people each paying one dollar to ride elevators to the observation decks in 1931. In its first year of operation, the observation deck made approximately $2 million in revenue, as much as its owners made in rent that year. By 1936, the observation deck was crowded on a daily basis, with food and drink available for purchase at the top, and by 1944 the building had received its five-millionth visitor. In 1931, NBC took up tenancy, leasing space on the 85th floor for radio broadcasts. From the outset the building was in debt, losing $1 million per year by 1935. Real estate developer Seymour Durst recalled that the building was so underused in 1936 that there was no elevator service above the 45th floor, as the building above the 41st floor was empty except for the NBC offices and the Raskob/Du Pont offices on the 81st floor.

Other events

Per the original plans, the Empire State Building's spire was intended to be an airship docking station. Raskob and Smith had proposed dirigible ticketing offices and passenger waiting rooms on the 86th floor, while the airships themselves would be tied to the spire at the equivalent of the building's 106th floor. An elevator would ferry passengers from the 86th to the 101st floor after they had checked in on the 86th floor, after which passengers would have climbed steep ladders to board the airship. The idea, however, was impractical and dangerous due to powerful updrafts caused by the building itself, the wind currents across Manhattan, and the spires of nearby skyscrapers. Furthermore, even if the airship were to successfully navigate all these obstacles, its crew would have to jettison some ballast by releasing water onto the streets below in order to maintain stability, and then tie the craft's nose to the spire with no mooring lines securing the tail end of the craft. On September 15, 1931, a small commercial United States Navy airship circled 25 times in 45-mile-per-hour (72 km/h) winds. The airship then attempted to dock at the mast, but its ballast spilled and the craft was rocked by unpredictable eddies. The near-disaster scuttled plans to turn the building's spire into an airship terminal, although one blimp did manage to make a single newspaper delivery afterward.

On July 28, 1945, a B-25 Mitchell bomber crashed into the north side of the Empire State Building, between the 79th and 80th floors. One engine completely penetrated the building and landed in a neighboring block, while the other engine and part of the landing gear plummeted down an elevator shaft. Fourteen people were killed in the incident, but the building escaped severe damage and was reopened two days later.

Profitability

By the 1940s, the Empire State Building was 98 percent occupied. The structure broke even for the first time in the 1950s. At the time, mass transit options in the building's vicinity were limited compared to the present day. Despite this challenge, the Empire State Building began to attract renters due to its reputation. A 222-foot (68 m) radio antenna was erected on top of the towers starting in 1950, allowing the area's television stations to be broadcast from the building.

Despite the turnaround in the building's fortunes, Raskob listed it for sale in 1951, with a minimum asking price of $50 million. The property was purchased by business partners Roger L. Stevens, Henry Crown, Alfred R. Glancy and Ben Tobin. The sale was brokered by the Charles F. Noyes Company, a prominent real estate firm in upper Manhattan, for $51 million, the highest price paid for a single structure at the time. By this time, the Empire State had been fully leased for several years with a waiting list of parties looking to lease space in the building, according to the Cortland Standard. That same year, six news companies formed a partnership to pay a combined annual fee of $600,000 to use the building's antenna, which was completed in 1953. Crown bought out his partners' ownership stakes in 1954, becoming the sole owner. The following year, the American Society of Civil Engineers named the building one of the "Seven Modern Civil Engineering Wonders".

In 1961, Lawrence A. Wien signed a contract to purchase the Empire State Building for $65 million, with Harry B. Helmsley acting as partners in the building's operating lease. This became the new highest price for a single structure. Over 3,000 people paid $10,000 for one share each in a company called Empire State Building Associates. The company in turn subleased the building to another company headed by Helmsley and Wien, raising $33 million of the funds needed to pay the purchase price. In a separate transaction, the land underneath the building was sold to Prudential Insurance for $29 million. Helmsley, Wien, and Peter Malkin quickly started a program of minor improvement projects, including the first-ever full-building facade refurbishment and window-washing in 1962, the installation of new flood lights on the 72nd floor in 1964, and replacement of the manually operated elevators with automatic units in 1966. The little-used western end of the second floor was used as a storage space until 1964, at which point it received escalators to the first floor as part of its conversion into a highly sought retail area.

Loss of "tallest building" title

In 1961, the same year that Helmsley, Wien, and Malkin had purchased the Empire State Building, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey formally backed plans for a new World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan. The plan originally included 66-story twin towers with column-free open spaces. The Empire State's owners and real estate speculators were worried that the twin towers' 7.6 million square feet (710,000 m) of office space would create a glut of rentable space in Manhattan as well as take away the Empire State Building's profits from lessees. A revision in the World Trade Center's plan brought the twin towers to 1,370 feet (420 m) each or 110 stories, taller than the Empire State. Opponents of the new project included prominent real-estate developer Robert Tishman, as well as Wien's Committee for a Reasonable World Trade Center. In response to Wien's opposition, Port Authority executive director Austin J. Tobin said that Wien was only opposing the project because it would overshadow his Empire State Building as the world's tallest building.

The World Trade Center's twin towers started construction in 1966. The following year, the Ostankino Tower succeeded the Empire State Building as the tallest freestanding structure in the world. In 1970, the Empire State surrendered its position as the world's tallest building, when the World Trade Center's still-under-construction North Tower surpassed it, on October 19; the North Tower was topped out on December 23, 1970.

In December 1975, the observation deck was opened on the 110th floor of the Twin Towers, significantly higher than the 86th floor observatory on the Empire State Building. The latter was also losing revenue during this period, particularly as a number of broadcast stations had moved to the World Trade Center in 1971; although the Port Authority continued to pay the broadcasting leases for the Empire State until 1984. The Empire State Building was still seen as prestigious, having seen its forty-millionth visitor in March 1971.

1980s and 1990s

By 1980, there were nearly two million annual visitors, although a building official had previously estimated between 1.5 million and 1.75 million annual visitors. The building received its own ZIP code in May 1980 in a roll out of 63 new postal codes in Manhattan. At the time, its tenants collectively received 35,000 pieces of mail daily. The Empire State Building celebrated its 50th anniversary on May 1, 1981, with a much-publicized, but poorly received, laser light show, as well as an "Empire State Building Week" that ran through to May 8. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) voted to designate the building and its lobby as city landmarks on May 19, 1981,

Capital improvements were made to the Empire State Building during the early to mid-1990s at a cost of $55 million. Because all of the building's windows were being replaced at the same time, the LPC mandated a paint-color test for the windows; the test revealed that the Empire State Building's original windows were actually red. The improvements also entailed replacing alarm systems, elevators, windows, and air conditioning; making the observation deck compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA); and refurbishing the limestone facade. The observation deck renovation was added after disability rights groups and the United States Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against the building in 1992, in what was the first lawsuit filed by an organization under the new law. A settlement was reached in 1994, in which Empire State Building Associates agreed to add ADA-compliant elements, such as new elevators, ramps, and automatic doors, during the renovation.

Prudential sold the land under the building in 1991 for $42 million to a buyer representing hotelier Hideki Yokoi [ja], who was imprisoned at the time in connection with the deadly Hotel New Japan Fire [ja] at the Hotel New Japan [ja] in Tokyo. In 1994, Donald Trump entered into a joint-venture agreement with Yokoi, with a shared goal of breaking the Empire State Building's lease on the land in an effort to gain total ownership of the building so that, if successful, the two could reap the potential profits of merging the ownership of the building with the land beneath it. Having secured a half-ownership of the land, Trump devised plans to take ownership of the building itself so he could renovate it, even though Helmsley and Malkin had already started their refurbishment project. He sued Empire State Building Associates in February 1995, claiming that the latter had caused the building to become a "high-rise slum" and a "second-rate, rodent-infested" office tower. Trump had intended to have Empire State Building Associates evicted for violating the terms of their lease, but was denied. This led to Helmsley's companies countersuing Trump in May. This sparked a series of lawsuits and countersuits that lasted several years, partly arising from Trump's desire to obtain the building's master lease by taking it from Empire State Building Associates. Upon Harry Helmsley's death in 1997, the Malkins sued Helmsley's widow, Leona Helmsley, for control of the building.

21st century

2000s

Following the destruction of the World Trade Center during the September 11 attacks, the Empire State Building again became the tallest building in New York City, but was only the second-tallest building in the Americas after the Sears (later Willis) Tower in Chicago. As a result of the attacks, transmissions from nearly all of the city's commercial television and FM radio stations were again broadcast from the Empire State Building. The attacks also led to an increase in security due to persistent terror threats against prominent sites in New York City.

In 2002, Trump and Yokoi sold their land claim to the Empire State Building Associates, now headed by Malkin, in a $57.5 million transaction. This action merged the building's title and lease for the first time in half a century. Despite the lingering threat posed by the 9/11 attacks, the Empire State Building remained popular with 3.5 million visitors to the observatories in 2004, compared to about 2.8 million in 2003.

Even though she maintained her ownership stake in the building until the post-consolidation IPO in October 2013, Leona Helmsley handed over day-to-day operations of the building in 2006 to Peter Malkin's company. In 2008, the building was temporarily "stolen" by the New York Daily News to show how easy it was to transfer the deed on a property, since city clerks were not required to validate the submitted information, as well as to help demonstrate how fraudulent deeds could be used to obtain large mortgages and then have individuals disappear with the money. The paperwork submitted to the city included the names of Fay Wray, the famous star of King Kong, and Willie Sutton, a notorious New York bank robber. The newspaper then transferred the deed back over to the legitimate owners, who at that time were Empire State Land Associates.

2010s to present

Starting in 2009, the building's public areas received a $550 million renovation, with improvements to the air conditioning and waterproofing, renovations to the observation deck and main lobby, and relocation of the gift shop to the 80th floor. About $120 million was spent on improving the energy efficiency of the building, with the goal of reducing energy emissions by 38% within five years. For example, all of the windows were refurbished onsite into film-coated "superwindows" which block heat but pass light. Air conditioning operating costs on hot days were reduced, saving $17 million of the project's capital cost immediately and partially funding some of the other retrofits. The Empire State Building won the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold for Existing Buildings rating in September 2011, as well as the World Federation of Great Towers' Excellence in Environment Award for 2010. For the LEED Gold certification, the building's energy reduction was considered, as was a large purchase of carbon offsets. Other factors included low-flow bathroom fixtures, green cleaning supplies, and use of recycled paper products.

On April 30, 2012, One World Trade Center topped out, surpassing the Empire State Building as the city's tallest skyscraper. By 2014, the building was owned by the Empire State Realty Trust (ESRT), with Anthony Malkin as chairman, CEO, and president. The ESRT was a public company, having begun trading publicly on the New York Stock Exchange the previous year. In August 2016, the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) was issued new fully diluted shares equivalent to 9.9% of the trust; this investment gave them partial ownership of the entirety of the ESRT's portfolio, and as a result, partial ownership of the Empire State Building. The trust's president John Kessler called it an "endorsement of the company's irreplaceable assets". The investment has been described by the real-estate magazine The Real Deal as "an unusual move for a sovereign wealth fund", as these funds typically buy direct stakes in buildings rather than real estate companies. Other foreign entities that have a stake in the ESRT include investors from Norway, Japan, and Australia.

A renovation of the Empire State Building was commenced in the 2010s to further improve energy efficiency, public areas, and amenities. In August 2018, to improve the flow of visitor traffic, the main visitor's entrance was shifted to 20 West 34th Street as part of a major renovation of the observatory lobby. The new lobby includes several technological features, including large LED panels, digital ticket kiosks in nine languages, and a two-story architectural model of the building surrounded by two metal staircases. The first phase of the renovation, completed in 2019, features an updated exterior lighting system and digital hosts. The new lobby also features free Wi-Fi provided for those waiting. A 10,000-square-foot (930 m) exhibit with nine galleries opened in July 2019. The 102nd floor observatory, the third phase of the redesign, reopened to the public on October 12, 2019. That portion of the project included outfitting the space with floor-to-ceiling glass windows and a brand-new glass elevator. The final portion of the renovations to be completed was a new observatory on the 80th floor, which opened on December 2, 2019. In total, the renovation cost $160 million or $165 million and took four years to finish.

A comprehensive restoration of the building's mooring and antenna masts also began in June 2019. Antennas on the mooring mast were removed or relocated to the upper mast, while the aluminum panels were cleaned and coated with silver paint. To minimize disruption to the observation decks, the restoration work took place at night. The project was completed by late 2020.

Height records

The longest world record held by the Empire State Building was for the tallest skyscraper (to structural height), which it held for 42 years until it was surpassed by the North Tower of the World Trade Center in October 1970. The Empire State Building was also the tallest human-made structure in the world before it was surpassed by the Griffin Television Tower Oklahoma (KWTV Mast) in 1954, and the tallest freestanding structure in the world until the completion of the Ostankino Tower in 1967. An early-1970s proposal to dismantle the spire and replace it with an additional 11 floors, which would have brought the building's height to 1,494 feet (455 m) and made it once again the world's tallest at the time, was considered but ultimately rejected.

With the destruction of the World Trade Center in the September 11 attacks, the Empire State Building again became the tallest building in New York City, and the second-tallest building in the Americas, surpassed only by the Willis Tower in Chicago. The Empire State Building remained the tallest building in New York until the new One World Trade Center reached a greater height in April 2012. As of 2022, it is the seventh-tallest building in New York City and the tenth-tallest in the United States. The Empire State Building is the 49th-tallest in the world as of February 2021. It is also the eleventh-tallest freestanding structure in the Americas behind the tallest U.S. buildings and the CN Tower.

Notable tenants

As of 2013, the building housed around 1,000 businesses. Current tenants include:

- Air China

- Boy Scouts of America, Greater New York Councils

- Bulova

- Corgan

- Coty

- Croatian National Tourist Board

- Expedia Group

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

- Global Brands Group

- Filipino Reporter

- Helios and Matheson

- HNTB

- Human Rights Foundation

- Human Rights Watch

- JCDecaux

- Kaplan International Center

- Li & Fung

- Noven Pharmaceuticals

- Palo Alto Networks

- People's Daily

- Qatar Airways

- RaySearch Laboratories

- Shutterstock

- Skanska

- Turkish Airlines

- Workday, Inc.

- World Monuments Fund

Former tenants include:

- The National Catholic Welfare Council (now Catholic Relief Services, located in Baltimore)

- The King's College (now located at 56 Broadway)

- China National Tourist Office (now located at 370 Lexington Avenue)

- National Film Board of Canada (now located at 1123 Broadway)

- Nathaniel Branden Institute

- Schenley Industries

- YWCA of the USA (relocated to Washington, DC)

Incidents

1945 plane crash

Main article: B-25 Empire State Building crash

At 9:40 am on July 28, 1945, a B-25 Mitchell bomber, piloted in thick fog by Lieutenant Colonel William Franklin Smith Jr., crashed into the north side of the Empire State Building between the 79th and 80th floors (then the offices of the National Catholic Welfare Council). One engine completely penetrated the building, landing on the roof of a nearby building where it started a fire that destroyed a penthouse. The other engine and part of the landing gear plummeted down an elevator shaft, causing a fire that was extinguished in 40 minutes. Fourteen people were killed in the incident. Elevator operator Betty Lou Oliver fell 75 stories and survived, which still holds the Guinness World Record for the longest survived elevator fall recorded.

Despite the damage and loss of life, many floors were open two days later. The crash helped spur the passage of the long-pending Federal Tort Claims Act of 1946, as well as the insertion of retroactive provisions into the law, allowing people to sue the government for the incident. Also as a result of the crash, the Civil Aeronautics Administration enacted strict regulations regarding flying over New York City, setting a minimum flying altitude of 2,500 feet (760 m) above sea level regardless of the weather conditions.

A year later, on July 24, 1946, another airplane narrowly missed striking the building. The unidentified twin-engine plane scraped past the observation deck, frightening the tourists there.

2000 elevator plunge

On January 24, 2000, an elevator in the building suddenly descended 40 stories after a cable that controlled the cabin's maximum speed was severed. The elevator fell from the 44th floor to the fourth floor, where a narrowed elevator shaft provided a second safety system. Despite the 40-floor fall, both of the passengers in the cabin at the time were only slightly injured. After the fall, building inspectors reviewed all of the building's elevators.

Suicide attempts

Because of the building's iconic status, it and other Midtown landmarks are common locations for suicide attempts. More than 30 people have attempted suicide over the years by jumping from the upper parts of the building, with most attempts being successful.

The first suicide from the building occurred on April 7, 1931, before it was even completed, when a carpenter who had been laid-off went to the 58th floor and jumped. The first suicide after the building's opening occurred from the 86th floor observatory in February 1935, when Irma P. Eberhardt fell 1,029 feet (314 m) onto a marquee sign. On December 16, 1943, William Lloyd Rambo jumped to his death from the 86th floor, landing amidst Christmas shoppers on the street below. In the early morning of September 27, 1946, shell-shocked Marine Douglas W. Brashear Jr. jumped from the 76th-floor window of the Grant Advertising Agency; police found his shoes 50 feet (15 m) from his body.

On May 1, 1947, Evelyn McHale leapt to her death from the 86th floor observation deck and landed on a limousine parked at the curb. Photography student Robert Wiles took a photo of McHale's oddly intact corpse a few minutes after her death. The police found a suicide note among possessions that she left on the observation deck: "He is much better off without me.... I wouldn't make a good wife for anybody". The photo ran in the May 12, 1947, edition of Life magazine and is often referred to as "The Most Beautiful Suicide". It was later used by visual artist Andy Warhol in one of his prints entitled Suicide (Fallen Body). A 7-foot (2.1 m) mesh fence was put up around the 86th floor terrace in December 1947 after five people tried to jump during a three-week span in October and November of that year. By then, sixteen people had died from suicide jumps.