| Fourier transforms |

|---|

In mathematics, the Fourier transform (FT) is an integral transform that takes a function as input and outputs another function that describes the extent to which various frequencies are present in the original function. The output of the transform is a complex-valued function of frequency. The term Fourier transform refers to both this complex-valued function and the mathematical operation. When a distinction needs to be made, the output of the operation is sometimes called the frequency domain representation of the original function. The Fourier transform is analogous to decomposing the sound of a musical chord into the intensities of its constituent pitches.

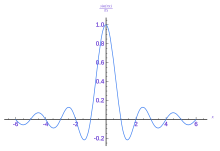

Functions that are localized in the time domain have Fourier transforms that are spread out across the frequency domain and vice versa, a phenomenon known as the uncertainty principle. The critical case for this principle is the Gaussian function, of substantial importance in probability theory and statistics as well as in the study of physical phenomena exhibiting normal distribution (e.g., diffusion). The Fourier transform of a Gaussian function is another Gaussian function. Joseph Fourier introduced sine and cosine transforms (which correspond to the imaginary and real components of the modern Fourier transform) in his study of heat transfer, where Gaussian functions appear as solutions of the heat equation.

The Fourier transform can be formally defined as an improper Riemann integral, making it an integral transform, although this definition is not suitable for many applications requiring a more sophisticated integration theory. For example, many relatively simple applications use the Dirac delta function, which can be treated formally as if it were a function, but the justification requires a mathematically more sophisticated viewpoint.

The Fourier transform can also be generalized to functions of several variables on Euclidean space, sending a function of 3-dimensional 'position space' to a function of 3-dimensional momentum (or a function of space and time to a function of 4-momentum). This idea makes the spatial Fourier transform very natural in the study of waves, as well as in quantum mechanics, where it is important to be able to represent wave solutions as functions of either position or momentum and sometimes both. In general, functions to which Fourier methods are applicable are complex-valued, and possibly vector-valued. Still further generalization is possible to functions on groups, which, besides the original Fourier transform on R or R, notably includes the discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT, group = Z), the discrete Fourier transform (DFT, group = Z mod N) and the Fourier series or circular Fourier transform (group = S, the unit circle ≈ closed finite interval with endpoints identified). The latter is routinely employed to handle periodic functions. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) is an algorithm for computing the DFT.

Definition

The Fourier transform of a complex-valued (Lebesgue) integrable function on the real line, is the complex valued function , defined by the integral

Fourier transform|

| Eq.1 |

Evaluating the Fourier transform for all values of produces the frequency-domain function. Though, in general, the integral can diverge at some frequencies, if decays with all derivatives, i.e., then converges for all frequencies and, by the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma, also decays with all derivatives.

First introduced in Fourier's Analytical Theory of Heat., the corresponding inversion formula for "sufficiently nice" functions is given by the Fourier inversion theorem, i.e.,

Inverse transform|

| Eq.2 |

The functions and are referred to as a Fourier transform pair. A common notation for designating transform pairs is: for example

By analogy, the Fourier series can be regarded as abstract Fourier transform on the group of integers. That is, the synthesis of a sequence of complex numbers is defined by the Fourier transform such that are given by the inversion formula, i.e., the analysis for some complex-valued, -periodic function defined on a bounded interval . When the constituent frequencies are a continuum: and .

In other words, on the finite interval the function has a discrete decomposition in the periodic functions . On the infinite interval the function has a continuous decomposition in periodic functions .

Lebesgue integrable functions

See also: Lp space § Lp spaces and Lebesgue integralsA measurable function is called (Lebesgue) integrable if the Lebesgue integral of its absolute value is finite: If is Lebesgue integrable then the Fourier transform, given by Eq.1, is well-defined for all . Furthermore, is bounded, uniformly continuous and (by the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma) zero at infinity.

The space is the space of measurable functions for which the norm is finite, modulo the equivalence relation of equality almost everywhere. The Fourier transform is one-to-one on . However, there is no easy characterization of the image, and thus no easy characterization of the inverse transform. In particular, Eq.2 is no longer valid, as it was stated only under the hypothesis that decayed with all derivatives.

While Eq.1 defines the Fourier transform for (complex-valued) functions in , it is not well-defined for other integrability classes, most importantly the space of square-integrable functions . For example, the function is in but not , so the integral Eq.1 diverges. However, the Fourier transform on the dense subspace admits a unique continuous extension to a unitary operator on . This extension is important in part because the Fourier transform preserves the space . That is, unlike the case of , both the Fourier transform and its inverse act on same function space .

In such cases, the Fourier transform can be obtained explicitly by regularizing the integral, and then passing to a limit. In practice, the integral is often regarded as an improper integral instead of a proper Lebesgue integral, but sometimes for convergence one needs to use weak limit or principal value instead of the (pointwise) limits implicit in an improper integral. Titchmarsh (1986) and Dym & McKean (1985) each gives three rigorous ways of extending the Fourier transform to square integrable functions using this procedure. A general principle in working with the Fourier transform is that Gaussians are dense in , and the various features of the Fourier transform, such as its unitarity, are easily inferred for Gaussians. Many of the properties of the Fourier transform, can then be proven from two facts about Gaussians:

- that is its own Fourier transform; and

- that the Gaussian integral

A feature of the Fourier transform is that it is a homomorphism of Banach algebras from equipped with the convolution operation to the Banach algebra of continuous functions under the (supremum) norm. The conventions chosen in this article are those of harmonic analysis, and are characterized as the unique conventions such that the Fourier transform is both unitary on L and an algebra homomorphism from L to L, without renormalizing the Lebesgue measure.

Angular frequency (ω)

When the independent variable () represents time (often denoted by ), the transform variable () represents frequency (often denoted by ). For example, if time is measured in seconds, then frequency is in hertz. The Fourier transform can also be written in terms of angular frequency, whose units are radians per second.

The substitution into Eq.1 produces this convention, where function is relabeled Unlike the Eq.1 definition, the Fourier transform is no longer a unitary transformation, and there is less symmetry between the formulas for the transform and its inverse. Those properties are restored by splitting the factor evenly between the transform and its inverse, which leads to another convention: Variations of all three conventions can be created by conjugating the complex-exponential kernel of both the forward and the reverse transform. The signs must be opposites.

| ordinary frequency ξ (Hz) | unitary | |

|---|---|---|

| angular frequency ω (rad/s) | unitary | |

| non-unitary |

| ordinary frequency ξ (Hz) | unitary | |

|---|---|---|

| angular frequency ω (rad/s) | unitary | |

| non-unitary |

Background

History

Main articles: Fourier analysis § History, and Fourier series § HistoryIn 1822, Fourier claimed (see Joseph Fourier § The Analytic Theory of Heat) that any function, whether continuous or discontinuous, can be expanded into a series of sines. That important work was corrected and expanded upon by others to provide the foundation for the various forms of the Fourier transform used since.

Complex sinusoids

The red sinusoid can be described by peak amplitude (1), peak-to-peak (2), RMS (3), and wavelength (4). The red and blue sinusoids have a phase difference of θ.

The red sinusoid can be described by peak amplitude (1), peak-to-peak (2), RMS (3), and wavelength (4). The red and blue sinusoids have a phase difference of θ.

In general, the coefficients are complex numbers, which have two equivalent forms (see Euler's formula):

The product with (Eq.2) has these forms: which conveys both amplitude and phase of frequency Likewise, the intuitive interpretation of Eq.1 is that multiplying by has the effect of subtracting from every frequency component of function Only the component that was at frequency can produce a non-zero value of the infinite integral, because (at least formally) all the other shifted components are oscillatory and integrate to zero. (see § Example)

It is noteworthy how easily the product was simplified using the polar form, and how easily the rectangular form was deduced by an application of Euler's formula.

Negative frequency

See also: Negative frequency § Simplifying the Fourier transformEuler's formula introduces the possibility of negative And Eq.1 is defined Only certain complex-valued have transforms (See Analytic signal. A simple example is ) But negative frequency is necessary to characterize all other complex-valued found in signal processing, partial differential equations, radar, nonlinear optics, quantum mechanics, and others.

For a real-valued Eq.1 has the symmetry property (see § Conjugation below). This redundancy enables Eq.2 to distinguish from But of course it cannot tell us the actual sign of because and are indistinguishable on just the real numbers line.

Fourier transform for periodic functions

The Fourier transform of a periodic function cannot be defined using the integral formula directly. In order for integral in Eq.1 to be defined the function must be absolutely integrable. Instead it is common to use Fourier series. It is possible to extend the definition to include periodic functions by viewing them as tempered distributions.

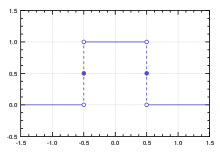

This makes it possible to see a connection between the Fourier series and the Fourier transform for periodic functions that have a convergent Fourier series. If is a periodic function, with period , that has a convergent Fourier series, then: where are the Fourier series coefficients of , and is the Dirac delta function. In other words, the Fourier transform is a Dirac comb function whose teeth are multiplied by the Fourier series coefficients.

Sampling the Fourier transform

For broader coverage of this topic, see Poisson summation formula.The Fourier transform of an integrable function can be sampled at regular intervals of arbitrary length These samples can be deduced from one cycle of a periodic function which has Fourier series coefficients proportional to those samples by the Poisson summation formula:

The integrability of ensures the periodic summation converges. Therefore, the samples can be determined by Fourier series analysis:

When has compact support, has a finite number of terms within the interval of integration. When does not have compact support, numerical evaluation of requires an approximation, such as tapering or truncating the number of terms.

Units

See also: Spectral density § UnitsThe frequency variable must have inverse units to the units of the original function's domain (typically named or ). For example, if is measured in seconds, should be in cycles per second or hertz. If the scale of time is in units of seconds, then another Greek letter is typically used instead to represent angular frequency (where ) in units of radians per second. If using for units of length, then must be in inverse length, e.g., wavenumbers. That is to say, there are two versions of the real line: one which is the range of and measured in units of and the other which is the range of and measured in inverse units to the units of These two distinct versions of the real line cannot be equated with each other. Therefore, the Fourier transform goes from one space of functions to a different space of functions: functions which have a different domain of definition.

In general, must always be taken to be a linear form on the space of its domain, which is to say that the second real line is the dual space of the first real line. See the article on linear algebra for a more formal explanation and for more details. This point of view becomes essential in generalizations of the Fourier transform to general symmetry groups, including the case of Fourier series.

That there is no one preferred way (often, one says "no canonical way") to compare the two versions of the real line which are involved in the Fourier transform—fixing the units on one line does not force the scale of the units on the other line—is the reason for the plethora of rival conventions on the definition of the Fourier transform. The various definitions resulting from different choices of units differ by various constants.

In other conventions, the Fourier transform has i in the exponent instead of −i, and vice versa for the inversion formula. This convention is common in modern physics and is the default for Wolfram Alpha, and does not mean that the frequency has become negative, since there is no canonical definition of positivity for frequency of a complex wave. It simply means that is the amplitude of the wave instead of the wave (the former, with its minus sign, is often seen in the time dependence for Sinusoidal plane-wave solutions of the electromagnetic wave equation, or in the time dependence for quantum wave functions). Many of the identities involving the Fourier transform remain valid in those conventions, provided all terms that explicitly involve i have it replaced by −i. In Electrical engineering the letter j is typically used for the imaginary unit instead of i because i is used for current.

When using dimensionless units, the constant factors might not even be written in the transform definition. For instance, in probability theory, the characteristic function Φ of the probability density function f of a random variable X of continuous type is defined without a negative sign in the exponential, and since the units of x are ignored, there is no 2π either:

(In probability theory, and in mathematical statistics, the use of the Fourier—Stieltjes transform is preferred, because so many random variables are not of continuous type, and do not possess a density function, and one must treat not functions but distributions, i.e., measures which possess "atoms".)

From the higher point of view of group characters, which is much more abstract, all these arbitrary choices disappear, as will be explained in the later section of this article, which treats the notion of the Fourier transform of a function on a locally compact Abelian group.

Properties

Let and represent integrable functions Lebesgue-measurable on the real line satisfying: We denote the Fourier transforms of these functions as and respectively.

Basic properties

The Fourier transform has the following basic properties:

Linearity

Time shifting

Frequency shifting

Time scaling

The case leads to the time-reversal property:

The transform of an even-symmetric real-valued function is also an even-symmetric real-valued function The time-shift, creates an imaginary component, (see § Symmmetry.

The transform of an even-symmetric real-valued function is also an even-symmetric real-valued function The time-shift, creates an imaginary component, (see § Symmmetry.

Symmetry

When the real and imaginary parts of a complex function are decomposed into their even and odd parts, there are four components, denoted below by the subscripts RE, RO, IE, and IO. And there is a one-to-one mapping between the four components of a complex time function and the four components of its complex frequency transform:

From this, various relationships are apparent, for example:

- The transform of a real-valued function is the conjugate symmetric function Conversely, a conjugate symmetric transform implies a real-valued time-domain.

- The transform of an imaginary-valued function is the conjugate antisymmetric function and the converse is true.

- The transform of a conjugate symmetric function is the real-valued function and the converse is true.

- The transform of a conjugate antisymmetric function is the imaginary-valued function and the converse is true.

Conjugation

(Note: the ∗ denotes complex conjugation.)

In particular, if is real, then is even symmetric (aka Hermitian function):

And if is purely imaginary, then is odd symmetric:

Real and imaginary parts

Zero frequency component

Substituting in the definition, we obtain:

The integral of over its domain is known as the average value or DC bias of the function.

Uniform continuity and the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma

The Fourier transform may be defined in some cases for non-integrable functions, but the Fourier transforms of integrable functions have several strong properties.

The Fourier transform of any integrable function is uniformly continuous and

By the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma,

However, need not be integrable. For example, the Fourier transform of the rectangular function, which is integrable, is the sinc function, which is not Lebesgue integrable, because its improper integrals behave analogously to the alternating harmonic series, in converging to a sum without being absolutely convergent.

It is not generally possible to write the inverse transform as a Lebesgue integral. However, when both and are integrable, the inverse equality holds for almost every x. As a result, the Fourier transform is injective on L(R).

Plancherel theorem and Parseval's theorem

Main articles: Plancherel theorem and Parseval's theoremLet f(x) and g(x) be integrable, and let f̂(ξ) and ĝ(ξ) be their Fourier transforms. If f(x) and g(x) are also square-integrable, then the Parseval formula follows: where the bar denotes complex conjugation.

The Plancherel theorem, which follows from the above, states that

Plancherel's theorem makes it possible to extend the Fourier transform, by a continuity argument, to a unitary operator on L(R). On L(R) ∩ L(R), this extension agrees with original Fourier transform defined on L(R), thus enlarging the domain of the Fourier transform to L(R) + L(R) (and consequently to L(R) for 1 ≤ p ≤ 2). Plancherel's theorem has the interpretation in the sciences that the Fourier transform preserves the energy of the original quantity. The terminology of these formulas is not quite standardised. Parseval's theorem was proved only for Fourier series, and was first proved by Lyapunov. But Parseval's formula makes sense for the Fourier transform as well, and so even though in the context of the Fourier transform it was proved by Plancherel, it is still often referred to as Parseval's formula, or Parseval's relation, or even Parseval's theorem.

See Pontryagin duality for a general formulation of this concept in the context of locally compact abelian groups.

Convolution theorem

Main article: Convolution theoremThe Fourier transform translates between convolution and multiplication of functions. If f(x) and g(x) are integrable functions with Fourier transforms f̂(ξ) and ĝ(ξ) respectively, then the Fourier transform of the convolution is given by the product of the Fourier transforms f̂(ξ) and ĝ(ξ) (under other conventions for the definition of the Fourier transform a constant factor may appear).

This means that if: where ∗ denotes the convolution operation, then:

In linear time invariant (LTI) system theory, it is common to interpret g(x) as the impulse response of an LTI system with input f(x) and output h(x), since substituting the unit impulse for f(x) yields h(x) = g(x). In this case, ĝ(ξ) represents the frequency response of the system.

Conversely, if f(x) can be decomposed as the product of two square integrable functions p(x) and q(x), then the Fourier transform of f(x) is given by the convolution of the respective Fourier transforms p̂(ξ) and q̂(ξ).

Cross-correlation theorem

Main articles: Cross-correlation and Wiener–Khinchin_theoremIn an analogous manner, it can be shown that if h(x) is the cross-correlation of f(x) and g(x): then the Fourier transform of h(x) is:

As a special case, the autocorrelation of function f(x) is: for which

Differentiation

Suppose f(x) is an absolutely continuous differentiable function, and both f and its derivative f′ are integrable. Then the Fourier transform of the derivative is given by More generally, the Fourier transformation of the nth derivative f is given by

Analogously, , so

By applying the Fourier transform and using these formulas, some ordinary differential equations can be transformed into algebraic equations, which are much easier to solve. These formulas also give rise to the rule of thumb "f(x) is smooth if and only if f̂(ξ) quickly falls to 0 for |ξ| → ∞." By using the analogous rules for the inverse Fourier transform, one can also say "f(x) quickly falls to 0 for |x| → ∞ if and only if f̂(ξ) is smooth."

Eigenfunctions

See also: Mehler kernel and Hermite polynomials § Hermite functions as eigenfunctions of the Fourier transformThe Fourier transform is a linear transform which has eigenfunctions obeying with

A set of eigenfunctions is found by noting that the homogeneous differential equation leads to eigenfunctions of the Fourier transform as long as the form of the equation remains invariant under Fourier transform. In other words, every solution and its Fourier transform obey the same equation. Assuming uniqueness of the solutions, every solution must therefore be an eigenfunction of the Fourier transform. The form of the equation remains unchanged under Fourier transform if can be expanded in a power series in which for all terms the same factor of either one of arises from the factors introduced by the differentiation rules upon Fourier transforming the homogeneous differential equation because this factor may then be cancelled. The simplest allowable leads to the standard normal distribution.

More generally, a set of eigenfunctions is also found by noting that the differentiation rules imply that the ordinary differential equation with constant and being a non-constant even function remains invariant in form when applying the Fourier transform to both sides of the equation. The simplest example is provided by which is equivalent to considering the Schrödinger equation for the quantum harmonic oscillator. The corresponding solutions provide an important choice of an orthonormal basis for L(R) and are given by the "physicist's" Hermite functions. Equivalently one may use where Hen(x) are the "probabilist's" Hermite polynomials, defined as

Under this convention for the Fourier transform, we have that

In other words, the Hermite functions form a complete orthonormal system of eigenfunctions for the Fourier transform on L(R). However, this choice of eigenfunctions is not unique. Because of there are only four different eigenvalues of the Fourier transform (the fourth roots of unity ±1 and ±i) and any linear combination of eigenfunctions with the same eigenvalue gives another eigenfunction. As a consequence of this, it is possible to decompose L(R) as a direct sum of four spaces H0, H1, H2, and H3 where the Fourier transform acts on Hek simply by multiplication by i.

Since the complete set of Hermite functions ψn provides a resolution of the identity they diagonalize the Fourier operator, i.e. the Fourier transform can be represented by such a sum of terms weighted by the above eigenvalues, and these sums can be explicitly summed:

This approach to define the Fourier transform was first proposed by Norbert Wiener. Among other properties, Hermite functions decrease exponentially fast in both frequency and time domains, and they are thus used to define a generalization of the Fourier transform, namely the fractional Fourier transform used in time–frequency analysis. In physics, this transform was introduced by Edward Condon. This change of basis functions becomes possible because the Fourier transform is a unitary transform when using the right conventions. Consequently, under the proper conditions it may be expected to result from a self-adjoint generator via

The operator is the number operator of the quantum harmonic oscillator written as

It can be interpreted as the generator of fractional Fourier transforms for arbitrary values of t, and of the conventional continuous Fourier transform for the particular value with the Mehler kernel implementing the corresponding active transform. The eigenfunctions of are the Hermite functions which are therefore also eigenfunctions of

Upon extending the Fourier transform to distributions the Dirac comb is also an eigenfunction of the Fourier transform.

Inversion and periodicity

Further information: Fourier inversion theorem and Fractional Fourier transformUnder suitable conditions on the function , it can be recovered from its Fourier transform . Indeed, denoting the Fourier transform operator by , so , then for suitable functions, applying the Fourier transform twice simply flips the function: , which can be interpreted as "reversing time". Since reversing time is two-periodic, applying this twice yields , so the Fourier transform operator is four-periodic, and similarly the inverse Fourier transform can be obtained by applying the Fourier transform three times: . In particular the Fourier transform is invertible (under suitable conditions).

More precisely, defining the parity operator such that , we have: These equalities of operators require careful definition of the space of functions in question, defining equality of functions (equality at every point? equality almost everywhere?) and defining equality of operators – that is, defining the topology on the function space and operator space in question. These are not true for all functions, but are true under various conditions, which are the content of the various forms of the Fourier inversion theorem.

This fourfold periodicity of the Fourier transform is similar to a rotation of the plane by 90°, particularly as the two-fold iteration yields a reversal, and in fact this analogy can be made precise. While the Fourier transform can simply be interpreted as switching the time domain and the frequency domain, with the inverse Fourier transform switching them back, more geometrically it can be interpreted as a rotation by 90° in the time–frequency domain (considering time as the x-axis and frequency as the y-axis), and the Fourier transform can be generalized to the fractional Fourier transform, which involves rotations by other angles. This can be further generalized to linear canonical transformations, which can be visualized as the action of the special linear group SL2(R) on the time–frequency plane, with the preserved symplectic form corresponding to the uncertainty principle, below. This approach is particularly studied in signal processing, under time–frequency analysis.

Connection with the Heisenberg group

The Heisenberg group is a certain group of unitary operators on the Hilbert space L(R) of square integrable complex valued functions f on the real line, generated by the translations (Ty f)(x) = f (x + y) and multiplication by e, (Mξ f)(x) = e f (x). These operators do not commute, as their (group) commutator is which is multiplication by the constant (independent of x) e ∈ U(1) (the circle group of unit modulus complex numbers). As an abstract group, the Heisenberg group is the three-dimensional Lie group of triples (x, ξ, z) ∈ R × U(1), with the group law

Denote the Heisenberg group by H1. The above procedure describes not only the group structure, but also a standard unitary representation of H1 on a Hilbert space, which we denote by ρ : H1 → B(L(R)). Define the linear automorphism of R by so that J = −I. This J can be extended to a unique automorphism of H1:

According to the Stone–von Neumann theorem, the unitary representations ρ and ρ ∘ j are unitarily equivalent, so there is a unique intertwiner W ∈ U(L(R)) such that This operator W is the Fourier transform.

Many of the standard properties of the Fourier transform are immediate consequences of this more general framework. For example, the square of the Fourier transform, W, is an intertwiner associated with J = −I, and so we have (Wf)(x) = f (−x) is the reflection of the original function f.

Complex domain

The integral for the Fourier transform can be studied for complex values of its argument ξ. Depending on the properties of f, this might not converge off the real axis at all, or it might converge to a complex analytic function for all values of ξ = σ + iτ, or something in between.

The Paley–Wiener theorem says that f is smooth (i.e., n-times differentiable for all positive integers n) and compactly supported if and only if f̂ (σ + iτ) is a holomorphic function for which there exists a constant a > 0 such that for any integer n ≥ 0, for some constant C. (In this case, f is supported on .) This can be expressed by saying that f̂ is an entire function which is rapidly decreasing in σ (for fixed τ) and of exponential growth in τ (uniformly in σ).

(If f is not smooth, but only L, the statement still holds provided n = 0.) The space of such functions of a complex variable is called the Paley—Wiener space. This theorem has been generalised to semisimple Lie groups.

If f is supported on the half-line t ≥ 0, then f is said to be "causal" because the impulse response function of a physically realisable filter must have this property, as no effect can precede its cause. Paley and Wiener showed that then f̂ extends to a holomorphic function on the complex lower half-plane τ < 0 which tends to zero as τ goes to infinity. The converse is false and it is not known how to characterise the Fourier transform of a causal function.

Laplace transform

See also: Laplace transform § Fourier transformThe Fourier transform f̂(ξ) is related to the Laplace transform F(s), which is also used for the solution of differential equations and the analysis of filters.

It may happen that a function f for which the Fourier integral does not converge on the real axis at all, nevertheless has a complex Fourier transform defined in some region of the complex plane.

For example, if f(t) is of exponential growth, i.e., for some constants C, a ≥ 0, then convergent for all 2πτ < −a, is the two-sided Laplace transform of f.

The more usual version ("one-sided") of the Laplace transform is

If f is also causal, and analytical, then: Thus, extending the Fourier transform to the complex domain means it includes the Laplace transform as a special case in the case of causal functions—but with the change of variable s = i2πξ.

From another, perhaps more classical viewpoint, the Laplace transform by its form involves an additional exponential regulating term which lets it converge outside of the imaginary line where the Fourier transform is defined. As such it can converge for at most exponentially divergent series and integrals, whereas the original Fourier decomposition cannot, enabling analysis of systems with divergent or critical elements. Two particular examples from linear signal processing are the construction of allpass filter networks from critical comb and mitigating filters via exact pole-zero cancellation on the unit circle. Such designs are common in audio processing, where highly nonlinear phase response is sought for, as in reverb.

Furthermore, when extended pulselike impulse responses are sought for signal processing work, the easiest way to produce them is to have one circuit which produces a divergent time response, and then to cancel its divergence through a delayed opposite and compensatory response. There, only the delay circuit in-between admits a classical Fourier description, which is critical. Both the circuits to the side are unstable, and do not admit a convergent Fourier decomposition. However, they do admit a Laplace domain description, with identical half-planes of convergence in the complex plane (or in the discrete case, the Z-plane), wherein their effects cancel.

In modern mathematics the Laplace transform is conventionally subsumed under the aegis Fourier methods. Both of them are subsumed by the far more general, and more abstract, idea of harmonic analysis.

Inversion

Still with , if is complex analytic for a ≤ τ ≤ b, then

by Cauchy's integral theorem. Therefore, the Fourier inversion formula can use integration along different lines, parallel to the real axis.

Theorem: If f(t) = 0 for t < 0, and |f(t)| < Ce for some constants C, a > 0, then for any τ < −a/2π.

This theorem implies the Mellin inversion formula for the Laplace transformation, for any b > a, where F(s) is the Laplace transform of f(t).

The hypotheses can be weakened, as in the results of Carleson and Hunt, to f(t) e being L, provided that f be of bounded variation in a closed neighborhood of t (cf. Dini test), the value of f at t be taken to be the arithmetic mean of the left and right limits, and that the integrals be taken in the sense of Cauchy principal values.

L versions of these inversion formulas are also available.

Fourier transform on Euclidean space

The Fourier transform can be defined in any arbitrary number of dimensions n. As with the one-dimensional case, there are many conventions. For an integrable function f(x), this article takes the definition: where x and ξ are n-dimensional vectors, and x · ξ is the dot product of the vectors. Alternatively, ξ can be viewed as belonging to the dual vector space , in which case the dot product becomes the contraction of x and ξ, usually written as ⟨x, ξ⟩.

All of the basic properties listed above hold for the n-dimensional Fourier transform, as do Plancherel's and Parseval's theorem. When the function is integrable, the Fourier transform is still uniformly continuous and the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma holds.

Uncertainty principle

Further information: Uncertainty principleGenerally speaking, the more concentrated f(x) is, the more spread out its Fourier transform f̂(ξ) must be. In particular, the scaling property of the Fourier transform may be seen as saying: if we squeeze a function in x, its Fourier transform stretches out in ξ. It is not possible to arbitrarily concentrate both a function and its Fourier transform.

The trade-off between the compaction of a function and its Fourier transform can be formalized in the form of an uncertainty principle by viewing a function and its Fourier transform as conjugate variables with respect to the symplectic form on the time–frequency domain: from the point of view of the linear canonical transformation, the Fourier transform is rotation by 90° in the time–frequency domain, and preserves the symplectic form.

Suppose f(x) is an integrable and square-integrable function. Without loss of generality, assume that f(x) is normalized:

It follows from the Plancherel theorem that f̂(ξ) is also normalized.

The spread around x = 0 may be measured by the dispersion about zero defined by

In probability terms, this is the second moment of |f(x)| about zero.

The uncertainty principle states that, if f(x) is absolutely continuous and the functions x·f(x) and f′(x) are square integrable, then

The equality is attained only in the case where σ > 0 is arbitrary and C1 = √2/√σ so that f is L-normalized. In other words, where f is a (normalized) Gaussian function with variance σ/2π, centered at zero, and its Fourier transform is a Gaussian function with variance σ/2π.

In fact, this inequality implies that: for any x0, ξ0 ∈ R.

In quantum mechanics, the momentum and position wave functions are Fourier transform pairs, up to a factor of the Planck constant. With this constant properly taken into account, the inequality above becomes the statement of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

A stronger uncertainty principle is the Hirschman uncertainty principle, which is expressed as: where H(p) is the differential entropy of the probability density function p(x): where the logarithms may be in any base that is consistent. The equality is attained for a Gaussian, as in the previous case.

Sine and cosine transforms

Main article: Sine and cosine transformsFourier's original formulation of the transform did not use complex numbers, but rather sines and cosines. Statisticians and others still use this form. An absolutely integrable function f for which Fourier inversion holds can be expanded in terms of genuine frequencies (avoiding negative frequencies, which are sometimes considered hard to interpret physically) λ by

This is called an expansion as a trigonometric integral, or a Fourier integral expansion. The coefficient functions a and b can be found by using variants of the Fourier cosine transform and the Fourier sine transform (the normalisations are, again, not standardised): and

Older literature refers to the two transform functions, the Fourier cosine transform, a, and the Fourier sine transform, b.

The function f can be recovered from the sine and cosine transform using together with trigonometric identities. This is referred to as Fourier's integral formula.

Spherical harmonics

Let the set of homogeneous harmonic polynomials of degree k on R be denoted by Ak. The set Ak consists of the solid spherical harmonics of degree k. The solid spherical harmonics play a similar role in higher dimensions to the Hermite polynomials in dimension one. Specifically, if f(x) = eP(x) for some P(x) in Ak, then f̂(ξ) = i f(ξ). Let the set Hk be the closure in L(R) of linear combinations of functions of the form f(|x|)P(x) where P(x) is in Ak. The space L(R) is then a direct sum of the spaces Hk and the Fourier transform maps each space Hk to itself and is possible to characterize the action of the Fourier transform on each space Hk.

Let f(x) = f0(|x|)P(x) (with P(x) in Ak), then where

Here J(n + 2k − 2)/2 denotes the Bessel function of the first kind with order n + 2k − 2/2. When k = 0 this gives a useful formula for the Fourier transform of a radial function. This is essentially the Hankel transform. Moreover, there is a simple recursion relating the cases n + 2 and n allowing to compute, e.g., the three-dimensional Fourier transform of a radial function from the one-dimensional one.

Restriction problems

In higher dimensions it becomes interesting to study restriction problems for the Fourier transform. The Fourier transform of an integrable function is continuous and the restriction of this function to any set is defined. But for a square-integrable function the Fourier transform could be a general class of square integrable functions. As such, the restriction of the Fourier transform of an L(R) function cannot be defined on sets of measure 0. It is still an active area of study to understand restriction problems in L for 1 < p < 2. It is possible in some cases to define the restriction of a Fourier transform to a set S, provided S has non-zero curvature. The case when S is the unit sphere in R is of particular interest. In this case the Tomas–Stein restriction theorem states that the restriction of the Fourier transform to the unit sphere in R is a bounded operator on L provided 1 ≤ p ≤ 2n + 2/n + 3.

One notable difference between the Fourier transform in 1 dimension versus higher dimensions concerns the partial sum operator. Consider an increasing collection of measurable sets ER indexed by R ∈ (0,∞): such as balls of radius R centered at the origin, or cubes of side 2R. For a given integrable function f, consider the function fR defined by:

Suppose in addition that f ∈ L(R). For n = 1 and 1 < p < ∞, if one takes ER = (−R, R), then fR converges to f in L as R tends to infinity, by the boundedness of the Hilbert transform. Naively one may hope the same holds true for n > 1. In the case that ER is taken to be a cube with side length R, then convergence still holds. Another natural candidate is the Euclidean ball ER = {ξ : |ξ| < R}. In order for this partial sum operator to converge, it is necessary that the multiplier for the unit ball be bounded in L(R). For n ≥ 2 it is a celebrated theorem of Charles Fefferman that the multiplier for the unit ball is never bounded unless p = 2. In fact, when p ≠ 2, this shows that not only may fR fail to converge to f in L, but for some functions f ∈ L(R), fR is not even an element of L.

Fourier transform on function spaces

See also: Riesz–Thorin theoremThe definition of the Fourier transform naturally extends from to as, for f ∈ L(R) whereby the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma may be formulated as the Fourier transform F : L(R) → L(R). This operator is bounded as which shows that its operator norm is bounded by 1. The image of L is a strict subset of C0(R), the space of continuous functions which vanish at infinity.

Similarly to the case of one variable, the Fourier transform can be defined on . Since the space of compactly supported smooth functions C

c(R) is dense in L(R), the Plancherel theorem allows one to extend the definition of the Fourier transform to general functions in L(R) by continuity arguments. The Fourier transform in L(R) is no longer given by an ordinary Lebesgue integral, although it can be computed by an improper integral, i.e.,

where the limit is taken in the L sense.

Furthermore, F : L(R) → L(R) is a unitary operator. For an operator to be unitary it is sufficient to show that it is bijective and preserves the inner product, so in this case these follow from the Fourier inversion theorem combined with the fact that for any f, g ∈ L(R) we have

In particular, the image of L(R) is itself under the Fourier transform.

On other L

For , the Fourier transform can be defined on by Marcinkiewicz interpolation, which amounts to decomposing such functions into a fat tail part in L plus a fat body part in L. In each of these spaces, the Fourier transform of a function in L(R) is in L(R), where q = p/p − 1 is the Hölder conjugate of p (by the Hausdorff–Young inequality). However, except for p = 2, the image is not easily characterized. Further extensions become more technical. The Fourier transform of functions in L for the range 2 < p < ∞ requires the study of distributions. In fact, it can be shown that there are functions in L with p > 2 so that the Fourier transform is not defined as a function.

Tempered distributions

Main article: Distribution (mathematics) § Tempered distributions and Fourier transformOne might consider enlarging the domain of the Fourier transform from L + L by considering generalized functions, or distributions. A distribution on R is a continuous linear functional on the space C

c(R) of compactly supported smooth functions, equipped with a suitable topology. The strategy is then to consider the action of the Fourier transform on C

c(R) and pass to distributions by duality. The obstruction to doing this is that the Fourier transform does not map C

c(R) to C

c(R). In fact the Fourier transform of an element in C

c(R) can not vanish on an open set; see the above discussion on the uncertainty principle.

The Fourier transform can also be defined for tempered distributions , dual to the space of Schwartz functions . A Schwartz function is a smooth function that decays at infinity, along with all of its derivatives, hence . The Fourier transform is an automorphism on the Schwartz space and, by duality, also an automorphism on the space of tempered distributions. The tempered distributions include well-behaved functions of polynomial growth, distributions of compact support as well as all the integrable functions mentioned above.

For the definition of the Fourier transform of a tempered distribution, let f and g be integrable functions, and let f̂ and ĝ be their Fourier transforms respectively. Then the Fourier transform obeys the following multiplication formula,

Every integrable function f defines (induces) a distribution Tf by the relation So it makes sense to define the Fourier transform of a tempered distribution by the duality: Extending this to all tempered distributions T gives the general definition of the Fourier transform.

Distributions can be differentiated and the above-mentioned compatibility of the Fourier transform with differentiation and convolution remains true for tempered distributions.

Generalizations

Fourier–Stieltjes transform on measurable spaces

See also: Bochner–Minlos theorem, Riesz–Markov–Kakutani representation theorem, and Fourier series § Fourier-Stieltjes seriesThe Fourier transform of a finite Borel measure μ on R is given by the continuous function: and called the Fourier-Stieltjes transform due to its connection with the Riemann-Stieltjes integral representation of (Radon) measures. If is the probability distribution of a random variable then its Fourier–Stieltjes transform is, by definition, a characteristic function. If, in addition, the probability distribution has a probability density function, this definition is subject to the usual Fourier transform. Stated more generally, when is absolutely continuous with respect to the Lebesgue measure, i.e., then and the Fourier-Stieltjes transform reduces to the usual definition of the Fourier transform. That is, the notable difference with the Fourier transform of integrable functions is that the Fourier-Stieltjes transform need not vanish at infinity, i.e., the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma fails for measures.

Bochner's theorem characterizes which functions may arise as the Fourier–Stieltjes transform of a positive measure on the circle.

One example of a finite Borel measure that is not a function is the Dirac measure. Its Fourier transform is a constant function (whose value depends on the form of the Fourier transform used).

Locally compact abelian groups

Main article: Pontryagin dualityThe Fourier transform may be generalized to any locally compact abelian group, i.e., an abelian group that is also a locally compact Hausdorff space such that the group operation is continuous. If G is a locally compact abelian group, it has a translation invariant measure μ, called Haar measure. For a locally compact abelian group G, the set of irreducible, i.e. one-dimensional, unitary representations are called its characters. With its natural group structure and the topology of uniform convergence on compact sets (that is, the topology induced by the compact-open topology on the space of all continuous functions from to the circle group), the set of characters Ĝ is itself a locally compact abelian group, called the Pontryagin dual of G. For a function f in L(G), its Fourier transform is defined by

The Riemann–Lebesgue lemma holds in this case; f̂(ξ) is a function vanishing at infinity on Ĝ.

The Fourier transform on T = R/Z is an example; here T is a locally compact abelian group, and the Haar measure μ on T can be thought of as the Lebesgue measure on [0,1). Consider the representation of T on the complex plane C that is a 1-dimensional complex vector space. There are a group of representations (which are irreducible since C is 1-dim) where for .

The character of such representation, that is the trace of for each and , is itself. In the case of representation of finite group, the character table of the group G are rows of vectors such that each row is the character of one irreducible representation of G, and these vectors form an orthonormal basis of the space of class functions that map from G to C by Schur's lemma. Now the group T is no longer finite but still compact, and it preserves the orthonormality of character table. Each row of the table is the function of and the inner product between two class functions (all functions being class functions since T is abelian) is defined as with the normalizing factor . The sequence is an orthonormal basis of the space of class functions .

For any representation V of a finite group G, can be expressed as the span ( are the irreps of G), such that . Similarly for and , . The Pontriagin dual is and for , is its Fourier transform for .

Gelfand transform

Main article: Gelfand representationThe Fourier transform is also a special case of Gelfand transform. In this particular context, it is closely related to the Pontryagin duality map defined above.

Given an abelian locally compact Hausdorff topological group G, as before we consider space L(G), defined using a Haar measure. With convolution as multiplication, L(G) is an abelian Banach algebra. It also has an involution * given by

Taking the completion with respect to the largest possibly C*-norm gives its enveloping C*-algebra, called the group C*-algebra C*(G) of G. (Any C*-norm on L(G) is bounded by the L norm, therefore their supremum exists.)

Given any abelian C*-algebra A, the Gelfand transform gives an isomorphism between A and C0(A^), where A^ is the multiplicative linear functionals, i.e. one-dimensional representations, on A with the weak-* topology. The map is simply given by It turns out that the multiplicative linear functionals of C*(G), after suitable identification, are exactly the characters of G, and the Gelfand transform, when restricted to the dense subset L(G) is the Fourier–Pontryagin transform.

Compact non-abelian groups

The Fourier transform can also be defined for functions on a non-abelian group, provided that the group is compact. Removing the assumption that the underlying group is abelian, irreducible unitary representations need not always be one-dimensional. This means the Fourier transform on a non-abelian group takes values as Hilbert space operators. The Fourier transform on compact groups is a major tool in representation theory and non-commutative harmonic analysis.

Let G be a compact Hausdorff topological group. Let Σ denote the collection of all isomorphism classes of finite-dimensional irreducible unitary representations, along with a definite choice of representation U on the Hilbert space Hσ of finite dimension dσ for each σ ∈ Σ. If μ is a finite Borel measure on G, then the Fourier–Stieltjes transform of μ is the operator on Hσ defined by where U is the complex-conjugate representation of U acting on Hσ. If μ is absolutely continuous with respect to the left-invariant probability measure λ on G, represented as for some f ∈ L(λ), one identifies the Fourier transform of f with the Fourier–Stieltjes transform of μ.

The mapping defines an isomorphism between the Banach space M(G) of finite Borel measures (see rca space) and a closed subspace of the Banach space C∞(Σ) consisting of all sequences E = (Eσ) indexed by Σ of (bounded) linear operators Eσ : Hσ → Hσ for which the norm is finite. The "convolution theorem" asserts that, furthermore, this isomorphism of Banach spaces is in fact an isometric isomorphism of C*-algebras into a subspace of C∞(Σ). Multiplication on M(G) is given by convolution of measures and the involution * defined by and C∞(Σ) has a natural C*-algebra structure as Hilbert space operators.

The Peter–Weyl theorem holds, and a version of the Fourier inversion formula (Plancherel's theorem) follows: if f ∈ L(G), then where the summation is understood as convergent in the L sense.

The generalization of the Fourier transform to the noncommutative situation has also in part contributed to the development of noncommutative geometry. In this context, a categorical generalization of the Fourier transform to noncommutative groups is Tannaka–Krein duality, which replaces the group of characters with the category of representations. However, this loses the connection with harmonic functions.

Alternatives

In signal processing terms, a function (of time) is a representation of a signal with perfect time resolution, but no frequency information, while the Fourier transform has perfect frequency resolution, but no time information: the magnitude of the Fourier transform at a point is how much frequency content there is, but location is only given by phase (argument of the Fourier transform at a point), and standing waves are not localized in time – a sine wave continues out to infinity, without decaying. This limits the usefulness of the Fourier transform for analyzing signals that are localized in time, notably transients, or any signal of finite extent.

As alternatives to the Fourier transform, in time–frequency analysis, one uses time–frequency transforms or time–frequency distributions to represent signals in a form that has some time information and some frequency information – by the uncertainty principle, there is a trade-off between these. These can be generalizations of the Fourier transform, such as the short-time Fourier transform, fractional Fourier transform, Synchrosqueezing Fourier transform, or other functions to represent signals, as in wavelet transforms and chirplet transforms, with the wavelet analog of the (continuous) Fourier transform being the continuous wavelet transform.

Example

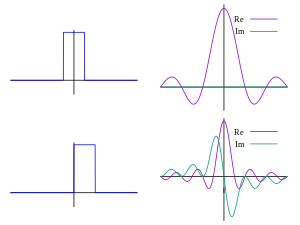

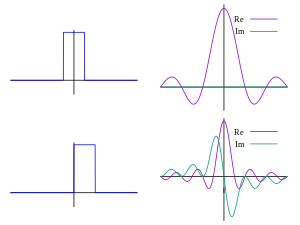

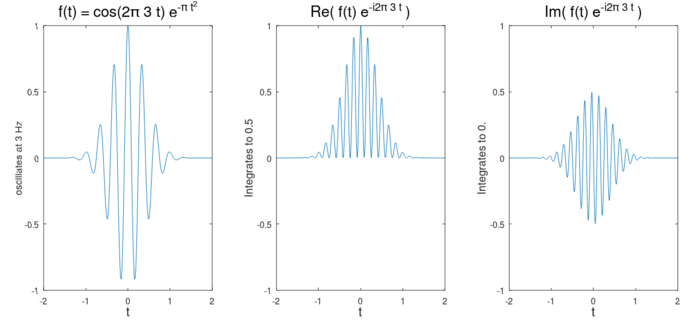

The following figures provide a visual illustration of how the Fourier transform's integral measures whether a frequency is present in a particular function. The first image depicts the function which is a 3 Hz cosine wave (the first term) shaped by a Gaussian envelope function (the second term) that smoothly turns the wave on and off. The next 2 images show the product which must be integrated to calculate the Fourier transform at +3 Hz. The real part of the integrand has a non-negative average value, because the alternating signs of and oscillate at the same rate and in phase, whereas and oscillate at the same rate but with orthogonal phase. The absolute value of the Fourier transform at +3 Hz is 0.5, which is relatively large. When added to the Fourier transform at -3 Hz (which is identical because we started with a real signal), we find that the amplitude of the 3 Hz frequency component is 1.

However, when you try to measure a frequency that is not present, both the real and imaginary component of the integral vary rapidly between positive and negative values. For instance, the red curve is looking for 5 Hz. The absolute value of its integral is nearly zero, indicating that almost no 5 Hz component was in the signal. The general situation is usually more complicated than this, but heuristically this is how the Fourier transform measures how much of an individual frequency is present in a function

-

Real and imaginary parts of the integrand for its Fourier transform at +5 Hz.

Real and imaginary parts of the integrand for its Fourier transform at +5 Hz.

-

Magnitude of its Fourier transform, with +3 and +5 Hz labeled.

Magnitude of its Fourier transform, with +3 and +5 Hz labeled.

To re-enforce an earlier point, the reason for the response at Hz is because and are indistinguishable. The transform of would have just one response, whose amplitude is the integral of the smooth envelope: whereas is

Applications

See also: Spectral density § Applications

Linear operations performed in one domain (time or frequency) have corresponding operations in the other domain, which are sometimes easier to perform. The operation of differentiation in the time domain corresponds to multiplication by the frequency, so some differential equations are easier to analyze in the frequency domain. Also, convolution in the time domain corresponds to ordinary multiplication in the frequency domain (see Convolution theorem). After performing the desired operations, transformation of the result can be made back to the time domain. Harmonic analysis is the systematic study of the relationship between the frequency and time domains, including the kinds of functions or operations that are "simpler" in one or the other, and has deep connections to many areas of modern mathematics.

Analysis of differential equations

Perhaps the most important use of the Fourier transformation is to solve partial differential equations. Many of the equations of the mathematical physics of the nineteenth century can be treated this way. Fourier studied the heat equation, which in one dimension and in dimensionless units is The example we will give, a slightly more difficult one, is the wave equation in one dimension,

As usual, the problem is not to find a solution: there are infinitely many. The problem is that of the so-called "boundary problem": find a solution which satisfies the "boundary conditions"

Here, f and g are given functions. For the heat equation, only one boundary condition can be required (usually the first one). But for the wave equation, there are still infinitely many solutions y which satisfy the first boundary condition. But when one imposes both conditions, there is only one possible solution.

It is easier to find the Fourier transform ŷ of the solution than to find the solution directly. This is because the Fourier transformation takes differentiation into multiplication by the Fourier-dual variable, and so a partial differential equation applied to the original function is transformed into multiplication by polynomial functions of the dual variables applied to the transformed function. After ŷ is determined, we can apply the inverse Fourier transformation to find y.

Fourier's method is as follows. First, note that any function of the forms satisfies the wave equation. These are called the elementary solutions.

Second, note that therefore any integral satisfies the wave equation for arbitrary a+, a−, b+, b−. This integral may be interpreted as a continuous linear combination of solutions for the linear equation.

Now this resembles the formula for the Fourier synthesis of a function. In fact, this is the real inverse Fourier transform of a± and b± in the variable x.

The third step is to examine how to find the specific unknown coefficient functions a± and b± that will lead to y satisfying the boundary conditions. We are interested in the values of these solutions at t = 0. So we will set t = 0. Assuming that the conditions needed for Fourier inversion are satisfied, we can then find the Fourier sine and cosine transforms (in the variable x) of both sides and obtain and

Similarly, taking the derivative of y with respect to t and then applying the Fourier sine and cosine transformations yields and

These are four linear equations for the four unknowns a± and b±, in terms of the Fourier sine and cosine transforms of the boundary conditions, which are easily solved by elementary algebra, provided that these transforms can be found.

In summary, we chose a set of elementary solutions, parametrized by ξ, of which the general solution would be a (continuous) linear combination in the form of an integral over the parameter ξ. But this integral was in the form of a Fourier integral. The next step was to express the boundary conditions in terms of these integrals, and set them equal to the given functions f and g. But these expressions also took the form of a Fourier integral because of the properties of the Fourier transform of a derivative. The last step was to exploit Fourier inversion by applying the Fourier transformation to both sides, thus obtaining expressions for the coefficient functions a± and b± in terms of the given boundary conditions f and g.

From a higher point of view, Fourier's procedure can be reformulated more conceptually. Since there are two variables, we will use the Fourier transformation in both x and t rather than operate as Fourier did, who only transformed in the spatial variables. Note that ŷ must be considered in the sense of a distribution since y(x, t) is not going to be L: as a wave, it will persist through time and thus is not a transient phenomenon. But it will be bounded and so its Fourier transform can be defined as a distribution. The operational properties of the Fourier transformation that are relevant to this equation are that it takes differentiation in x to multiplication by i2πξ and differentiation with respect to t to multiplication by i2πf where f is the frequency. Then the wave equation becomes an algebraic equation in ŷ: This is equivalent to requiring ŷ(ξ, f) = 0 unless ξ = ±f. Right away, this explains why the choice of elementary solutions we made earlier worked so well: obviously f̂ = δ(ξ ± f) will be solutions. Applying Fourier inversion to these delta functions, we obtain the elementary solutions we picked earlier. But from the higher point of view, one does not pick elementary solutions, but rather considers the space of all distributions which are supported on the (degenerate) conic ξ − f = 0.

We may as well consider the distributions supported on the conic that are given by distributions of one variable on the line ξ = f plus distributions on the line ξ = −f as follows: if Φ is any test function, where s+, and s−, are distributions of one variable.

Then Fourier inversion gives, for the boundary conditions, something very similar to what we had more concretely above (put Φ(ξ, f) = e, which is clearly of polynomial growth): and

Now, as before, applying the one-variable Fourier transformation in the variable x to these functions of x yields two equations in the two unknown distributions s± (which can be taken to be ordinary functions if the boundary conditions are L or L).

From a calculational point of view, the drawback of course is that one must first calculate the Fourier transforms of the boundary conditions, then assemble the solution from these, and then calculate an inverse Fourier transform. Closed form formulas are rare, except when there is some geometric symmetry that can be exploited, and the numerical calculations are difficult because of the oscillatory nature of the integrals, which makes convergence slow and hard to estimate. For practical calculations, other methods are often used.

The twentieth century has seen the extension of these methods to all linear partial differential equations with polynomial coefficients, and by extending the notion of Fourier transformation to include Fourier integral operators, some non-linear equations as well.

Fourier-transform spectroscopy

Main article: Fourier-transform spectroscopyThe Fourier transform is also used in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and in other kinds of spectroscopy, e.g. infrared (FTIR). In NMR an exponentially shaped free induction decay (FID) signal is acquired in the time domain and Fourier-transformed to a Lorentzian line-shape in the frequency domain. The Fourier transform is also used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and mass spectrometry.

Quantum mechanics

The Fourier transform is useful in quantum mechanics in at least two different ways. To begin with, the basic conceptual structure of quantum mechanics postulates the existence of pairs of complementary variables, connected by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. For example, in one dimension, the spatial variable q of, say, a particle, can only be measured by the quantum mechanical "position operator" at the cost of losing information about the momentum p of the particle. Therefore, the physical state of the particle can either be described by a function, called "the wave function", of q or by a function of p but not by a function of both variables. The variable p is called the conjugate variable to q. In classical mechanics, the physical state of a particle (existing in one dimension, for simplicity of exposition) would be given by assigning definite values to both p and q simultaneously. Thus, the set of all possible physical states is the two-dimensional real vector space with a p-axis and a q-axis called the phase space.

In contrast, quantum mechanics chooses a polarisation of this space in the sense that it picks a subspace of one-half the dimension, for example, the q-axis alone, but instead of considering only points, takes the set of all complex-valued "wave functions" on this axis. Nevertheless, choosing the p-axis is an equally valid polarisation, yielding a different representation of the set of possible physical states of the particle. Both representations of the wavefunction are related by a Fourier transform, such that or, equivalently,

Physically realisable states are L, and so by the Plancherel theorem, their Fourier transforms are also L. (Note that since q is in units of distance and p is in units of momentum, the presence of the Planck constant in the exponent makes the exponent dimensionless, as it should be.)

Therefore, the Fourier transform can be used to pass from one way of representing the state of the particle, by a wave function of position, to another way of representing the state of the particle: by a wave function of momentum. Infinitely many different polarisations are possible, and all are equally valid. Being able to transform states from one representation to another by the Fourier transform is not only convenient but also the underlying reason of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

The other use of the Fourier transform in both quantum mechanics and quantum field theory is to solve the applicable wave equation. In non-relativistic quantum mechanics, Schrödinger's equation for a time-varying wave function in one-dimension, not subject to external forces, is

This is the same as the heat equation except for the presence of the imaginary unit i. Fourier methods can be used to solve this equation.

In the presence of a potential, given by the potential energy function V(x), the equation becomes

The "elementary solutions", as we referred to them above, are the so-called "stationary states" of the particle, and Fourier's algorithm, as described above, can still be used to solve the boundary value problem of the future evolution of ψ given its values for t = 0. Neither of these approaches is of much practical use in quantum mechanics. Boundary value problems and the time-evolution of the wave function is not of much practical interest: it is the stationary states that are most important.

In relativistic quantum mechanics, Schrödinger's equation becomes a wave equation as was usual in classical physics, except that complex-valued waves are considered. A simple example, in the absence of interactions with other particles or fields, is the free one-dimensional Klein–Gordon–Schrödinger–Fock equation, this time in dimensionless units,

This is, from the mathematical point of view, the same as the wave equation of classical physics solved above (but with a complex-valued wave, which makes no difference in the methods). This is of great use in quantum field theory: each separate Fourier component of a wave can be treated as a separate harmonic oscillator and then quantized, a procedure known as "second quantization". Fourier methods have been adapted to also deal with non-trivial interactions.

Finally, the number operator of the quantum harmonic oscillator can be interpreted, for example via the Mehler kernel, as the generator of the Fourier transform .

Signal processing

The Fourier transform is used for the spectral analysis of time-series. The subject of statistical signal processing does not, however, usually apply the Fourier transformation to the signal itself. Even if a real signal is indeed transient, it has been found in practice advisable to model a signal by a function (or, alternatively, a stochastic process) which is stationary in the sense that its characteristic properties are constant over all time. The Fourier transform of such a function does not exist in the usual sense, and it has been found more useful for the analysis of signals to instead take the Fourier transform of its autocorrelation function.

The autocorrelation function R of a function f is defined by

This function is a function of the time-lag τ elapsing between the values of f to be correlated.

For most functions f that occur in practice, R is a bounded even function of the time-lag τ and for typical noisy signals it turns out to be uniformly continuous with a maximum at τ = 0.

The autocorrelation function, more properly called the autocovariance function unless it is normalized in some appropriate fashion, measures the strength of the correlation between the values of f separated by a time lag. This is a way of searching for the correlation of f with its own past. It is useful even for other statistical tasks besides the analysis of signals. For example, if f(t) represents the temperature at time t, one expects a strong correlation with the temperature at a time lag of 24 hours.

It possesses a Fourier transform,

This Fourier transform is called the power spectral density function of f. (Unless all periodic components are first filtered out from f, this integral will diverge, but it is easy to filter out such periodicities.)

The power spectrum, as indicated by this density function P, measures the amount of variance contributed to the data by the frequency ξ. In electrical signals, the variance is proportional to the average power (energy per unit time), and so the power spectrum describes how much the different frequencies contribute to the average power of the signal. This process is called the spectral analysis of time-series and is analogous to the usual analysis of variance of data that is not a time-series (ANOVA).

Knowledge of which frequencies are "important" in this sense is crucial for the proper design of filters and for the proper evaluation of measuring apparatuses. It can also be useful for the scientific analysis of the phenomena responsible for producing the data.

The power spectrum of a signal can also be approximately measured directly by measuring the average power that remains in a signal after all the frequencies outside a narrow band have been filtered out.

Spectral analysis is carried out for visual signals as well. The power spectrum ignores all phase relations, which is good enough for many purposes, but for video signals other types of spectral analysis must also be employed, still using the Fourier transform as a tool.

Other notations

Other common notations for include:

In the sciences and engineering it is also common to make substitutions like these:

So the transform pair can become

A disadvantage of the capital letter notation is when expressing a transform such as or which become the more awkward and

In some contexts such as particle physics, the same symbol may be used for both for a function as well as it Fourier transform, with the two only distinguished by their argument I.e. would refer to the Fourier transform because of the momentum argument, while would refer to the original function because of the positional argument. Although tildes may be used as in to indicate Fourier transforms, tildes may also be used to indicate a modification of a quantity with a more Lorentz invariant form, such as , so care must be taken. Similarly, often denotes the Hilbert transform of .

The interpretation of the complex function f̂(ξ) may be aided by expressing it in polar coordinate form in terms of the two real functions A(ξ) and φ(ξ) where: is the amplitude and is the phase (see arg function).

Then the inverse transform can be written: which is a recombination of all the frequency components of f(x). Each component is a complex sinusoid of the form e whose amplitude is A(ξ) and whose initial phase angle (at x = 0) is φ(ξ).

The Fourier transform may be thought of as a mapping on function spaces. This mapping is here denoted F and F(f) is used to denote the Fourier transform of the function f. This mapping is linear, which means that F can also be seen as a linear transformation on the function space and implies that the standard notation in linear algebra of applying a linear transformation to a vector (here the function f) can be used to write F f instead of F(f). Since the result of applying the Fourier transform is again a function, we can be interested in the value of this function evaluated at the value ξ for its variable, and this is denoted either as F f(ξ) or as (F f)(ξ). Notice that in the former case, it is implicitly understood that F is applied first to f and then the resulting function is evaluated at ξ, not the other way around.

In mathematics and various applied sciences, it is often necessary to distinguish between a function f and the value of f when its variable equals x, denoted f(x). This means that a notation like F(f(x)) formally can be interpreted as the Fourier transform of the values of f at x. Despite this flaw, the previous notation appears frequently, often when a particular function or a function of a particular variable is to be transformed. For example, is sometimes used to express that the Fourier transform of a rectangular function is a sinc function, or is used to express the shift property of the Fourier transform.

Notice, that the last example is only correct under the assumption that the transformed function is a function of x, not of x0.

As discussed above, the characteristic function of a random variable is the same as the Fourier–Stieltjes transform of its distribution measure, but in this context it is typical to take a different convention for the constants. Typically characteristic function is defined

As in the case of the "non-unitary angular frequency" convention above, the factor of 2π appears in neither the normalizing constant nor the exponent. Unlike any of the conventions appearing above, this convention takes the opposite sign in the exponent.

Computation methods

The appropriate computation method largely depends how the original mathematical function is represented and the desired form of the output function. In this section we consider both functions of a continuous variable, and functions of a discrete variable (i.e. ordered pairs of and values). For discrete-valued the transform integral becomes a summation of sinusoids, which is still a continuous function of frequency ( or ). When the sinusoids are harmonically-related (i.e. when the -values are spaced at integer multiples of an interval), the transform is called discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT).

Discrete Fourier transforms and fast Fourier transforms

Sampling the DTFT at equally-spaced values of frequency is the most common modern method of computation. Efficient procedures, depending on the frequency resolution needed, are described at Discrete-time Fourier transform § Sampling the DTFT. The discrete Fourier transform (DFT), used there, is usually computed by a fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithm.

Analytic integration of closed-form functions

Tables of closed-form Fourier transforms, such as § Square-integrable functions, one-dimensional and § Table of discrete-time Fourier transforms, are created by mathematically evaluating the Fourier analysis integral (or summation) into another closed-form function of frequency ( or ). When mathematically possible, this provides a transform for a continuum of frequency values.

Many computer algebra systems such as Matlab and Mathematica that are capable of symbolic integration are capable of computing Fourier transforms analytically. For example, to compute the Fourier transform of cos(6πt) e one might enter the command integrate cos(6*pi*t) exp(−pi*t^2) exp(-i*2*pi*f*t) from -inf to inf into Wolfram Alpha.

Numerical integration of closed-form continuous functions

Discrete sampling of the Fourier transform can also be done by numerical integration of the definition at each value of frequency for which transform is desired. The numerical integration approach works on a much broader class of functions than the analytic approach.

Numerical integration of a series of ordered pairs

If the input function is a series of ordered pairs, numerical integration reduces to just a summation over the set of data pairs. The DTFT is a common subcase of this more general situation.

Tables of important Fourier transforms

The following tables record some closed-form Fourier transforms. For functions f(x) and g(x) denote their Fourier transforms by f̂ and ĝ. Only the three most common conventions are included. It may be useful to notice that entry 105 gives a relationship between the Fourier transform of a function and the original function, which can be seen as relating the Fourier transform and its inverse.

Functional relationships, one-dimensional

The Fourier transforms in this table may be found in Erdélyi (1954) or Kammler (2000, appendix).

| Function | Fourier transform unitary, ordinary frequency |

Fourier transform unitary, angular frequency |

Fourier transform non-unitary, angular frequency |

Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitions | |||||

| 101 | Linearity | ||||

| 102 | Shift in time domain | ||||

| 103 | Shift in frequency domain, dual of 102 | ||||

| 104 | Scaling in the time domain. If |a| is large, then f(ax) is concentrated around 0 and spreads out and flattens. | ||||

| 105 | The same transform is applied twice, but x replaces the frequency variable (ξ or ω) after the first transform. | ||||

| 106 | n-order derivative.

As f is a Schwartz function | ||||

| 106.5 | Integration. Note: is the Dirac delta function and is the average (DC) value of such that | ||||

| 107 | This is the dual of 106 | ||||

| 108 | The notation f ∗ g denotes the convolution of f and g — this rule is the convolution theorem | ||||

| 109 | This is the dual of 108 | ||||

| 110 | For f(x) purely real | Hermitian symmetry. z indicates the complex conjugate. | |||

| 113 | For f(x) purely imaginary | z indicates the complex conjugate. | |||

| 114 | Complex conjugation, generalization of 110 and 113 | ||||