| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: copyediting, fact checking, wikifying, etc. Please help improve this article if you can. (February 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Garo | |

|---|---|

| A·chikku / আ·চিক্কু | |

| Native to | India and Bangladesh |

| Region | Meghalaya, Assam, Bangladesh |

| Ethnicity | Garo |

| Native speakers | 1,145,323 (2011) |

| Language family | Sino-Tibetan |

| Dialects |

|

| Writing system | Latin script Bengali-Assamese script A-Chik Tokbirim |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | grt |

| Glottolog | garo1247 |

| ELP | Garo |

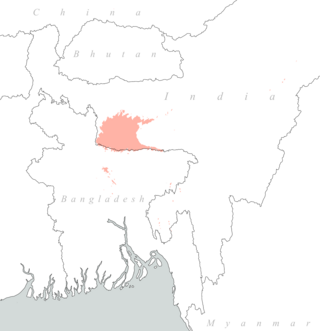

Map of Garo speaking areas Map of Garo speaking areas | |

Garo, also referred to by its endonym A·chikku, is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in the Northeast Indian states of Meghalaya, Assam, and Tripura. It is also spoken in certain areas of the neighbouring Bangladesh. According to the 2001 census, there are about 889,000 Garo speakers in India alone; another 130,000 are found in Bangladesh.

Geographical distribution

Ethnologue lists the following locations for Garo.

- Garo Hills division, Meghalaya

- Goalpara district, Kamrup district, Sivasagar, Karbi Anglong district, western Assam

- Kohima district, Nagaland

- Udaipur subdivision, South Tripura district, Tripura

- Kamalpur and Kailasahar subdivisions, North Tripura district, Tripura

- Sadar subdivision, West Tripura district, Tripura

- Jalpaiguri district and Koch Bihar district, West Bengal

- Mymensingh district, Tangail, Jamalpur, Sherpur, Netrokona, Gazipur, Sunamgonj, Sylhet, Moulvibazar, Dhaka, Gazipur, Bangladesh

Linguistic affiliation

Garo language belongs to the Baric group, a member of the Tibeto-Burmese subgroup of the Sino-Tibetan language family. The Boro-Garo subgroup is one of the longest recognised and most coherent subgroups of the Sino-Tibetan language family. This includes languages such as Garo language, Boro, Kokborok, Dimasa, Rabha, Atong, Tiwa, and Koch. Being closely related to each other, these languages have many features in common; and one can easily recognise the similarities even from a surface-level observation of a given data of words from these languages.

Orthography and standardisation

Towards the end of the 19th century, the American Baptist missionaries put the north-eastern dialect of Garo called A•we into writing, initially using the Bengali script. It was selected out of many others because the north-eastern region of Garo Hills was where rapid growth in the number of educated Garo people was taking place. Besides, the region was also where education was first imparted to the Garos. In course of time, the dialect became associated with educated culture. Today, a variant of the dialect can be heard among the speakers of Tura, a small town in the west-central part of Garo Hills, which is actually an Am•beng-speaking region. The political headquarters was established in Tura, after Garo Hills came under the complete control of the British Government in 1873. This led to the migration of educated north-easterners to the town, and a shift from its use of the native dialect to the dialect of the north-easterners. Tura also became the educational hub of Garo Hills, and in time, a de facto standard developed from the north-eastern dialect (A•we) which gradually became associated with the town and the educated Garo speech everywhere ever since. As regards Garo orthography, basic Latin alphabet completely replaced the Bengali script only by 1924, although a Latin-based alphabet had already been developed by the American missionaries in 1902.

The Latin-based Garo alphabet used today consists of 20 letters and a raised dot called "raka" (a symbol representing the glottal stop ). In typing, the raka is represented by an interpunct. The letters "f", "q", "v", "x", "y", and "z" are not considered to be part of the alphabet and appear only in borrowed words. There are two ways in which the alphabet "i" is pronounced: one is /i/ (usually in the word final position), while the other is the centralised vowel /ɨ/ (usually in the word initial and word medial position). Therefore, although Garo may morphologically possess five vowels, phonetically, it actually has six.

In Bangladesh, a variant of the Bengali script is still used alongside its Latin counterpart. Bengali and Assamese had been the mediums of instruction in educational institutions until 1924, and they have played a great role in the evolution of the modern Garo as we know it today. As a result, many Bengali and Assamese words entered the Garo lexicon. Recently there has also been a proliferation of English words entering the everyday Garo speech, owing to media and the preference of English-medium schools over those conducted in the vernacular. Hindi vocabulary is also making a slow but firm appearance in the language.

The Garo language is sometimes written with the alphabetic A•chik Tokbirim script, which was invented in 1979 by Arun Richil Marak. The names of each letter in this script were taken from natural phenomena. The script is used to some extent in the village of Bhabanipur in northwestern Bangladesh, and is also known as A•chik Garo Tokbirim.

Dialects

Accordingly, the term 'dialect' is politically defined as a 'non-official speech variety'. The Garo language comprises dialects such as A·we, Am·beng/A·beng, Matchi, Dual, Chisak, Ganching, and a few others. Marak (2013:134–135) lists the following dialects of Garo and their geographical distributions.

- The A•tong dialect is spoken in the South East of Garo Hills in the Simsang river valley. The majority of Atong speakers are concentrated in villages like Rongsu, Siju, Rongru A·sim, Badri, Chitmang, Nongal

- The Ruga dialect is spoken in a small area in the South Central part of Garo Hills in the Bugai river valley. Like Atong, Ruga is close to Koch and Rabha languages, and also to Atong than to the language of most Garos, but the shift to A·we and A·beng has gone farther along the Rugas than among the Atongs.

- The Chibok occupy the upper ridges of the Bugai River.

- The Me•gam occupy roughly the border between the Garo Hills and Khasi Hills.

- The Am·beng dialect is spoken in a large area beginning from the west of Bugai River, Ranggira plateau to the valley in the west and north. It is spoken across the boundaries in Bangladesh and south and north bank of Assam.

- A·we is spoken in a large stretch of the Brahmaputra valley roughly from Agia, Goalpara, to Doranggre, Amjonga to the border of Kamrup.

- The Matabeng dialect which is as almost similar to Am.beng dialect. It is found in the Arbella plateau, Dumindikgre, Rongwalkamgre, Chidekgre, Sanchonggre, Babadamgre, Rongram, Asanang etc.

- Gara Ganching is spoken in the southern part of Garo Hills. Gara Ganching speakers have settled in the Dareng and Rompa river valley.

- Dual is spoken in Sibbari, Kapasipara villages in the valley of the Dareng River. These villages are situated in the southern part of Garo Hills. Some Dual speakers also have settled in the villages of Balachanda and Chandakona in the western foothills of Garo Hills.

- The Matchi-Dual dialect is spoken in the Williamnagar area, in the Simsang valley. This dialect is a mixture of Matchi and Dual dialects.

- The Kamrup dialect is spoken in the villages of Gohalkona, Hahim, Santipur, and Ukiam in Kamrup District.

The speakers of these dialects can generally understand one another, although there are occasions where one who is unfamiliar with a dialect from another region requires explanation of certain words and expressions typical of that dialect. Research on the dialects of Garo, with the exception of A·we and Am·beng, is very much neglected; and many Garo dialects are being subsumed either the Standard or A·we or Am·beng. Although the de facto written and spoken standard grew out of A·we, they are not one and the same; there is marked variation in the intonation and the use of vocabulary between the two. It would be proper, therefore, to make a distinction between Standard A·we (spoken mainly in Tura) and Traditional A·we (still heard among the speakers in the north-eastern region of Garo Hills). There is also a great misconception among Garos regarding Atong, Ruga, and Me·gam. These languages are traditionally considered dialects of Garo. The speakers of Atong and Ruga languages are indeed Garos, ethnically; but their languages lack mutual intelligibility with the dialects of Garo and therefore linguistically distinct from the Garo language. Me∙gam people are ethnically Garo but Me.gam people of Khasi Hills has been influenced by Khasi language and hence the Me.gam of Khasi Hills is linguistically similar to Khasi.

Garo words

Greetings and wishes

- Namenga ma? - How are you?

- Namengaba - I'm fine or okay

- Pringnam - Good morning

- Walnam - Good night

- Attamnam - Good afternoon

- Ang•a nang•na Ka•saa or Anga nang•na ka•sara - I love you

- Na•a bachi re•angenga? - Where are you going?

- Anga Tura china re•angenga - I'm going to Tura

- Mi cha•jok ma? - Have you eaten rice?

- Anga mi Cha•aha or Cha•jok - I have eaten rice

Family

1. Ama - Mother

2. Apa - Father

3. Awang (Father's younger brother) - Uncle

4. Ade (Mother's younger sister) - Aunt

5. Mama (Mother's male siblings) - Uncle

6. Atchu or Bude - Grandfather

7. Ambi or Bitchi - Grandmother

8. Abi - Elder sister

9. Ano or Nono - Younger sister

10. Angjong or Jojong - Younger brother

Astronomy and meteorology

1. Sal - Sun

2. Jajong - Moon

3. Aski - Stars

4. Aram - Sky or clouds

5. Balwa - Wind or Air

6. Mikka - Rain

Status

Garo has been given the status of an associate official language (the main official being English) in the five Garo Hills districts of Meghalaya under the Meghalaya State Language Act, 2005.

The language is also used as the medium of instruction at the elementary stage in Government-run schools in the Garo Hills. Even at the secondary stage, in some schools, where English is the de jure medium of instruction, Garo is used alongside English – and sometimes even more than it – making the system more or less a bilingual one. In schools where English is the sole medium, Garo is taught only as a subject, as Modern Indian Language (M.I.L.). At the college level, students can opt for Garo Second Language (G.S.L.) besides the compulsory M.I.L. and even work towards a B.A. (Honours) in Garo.

In 1996, at the inception of its Tura campus, the North-Eastern Hill University established the Department of Garo, making it one of the first departments to be opened in the campus and "the only one of its kind in the world". The department offers M.A. M.Phil. and PhD programs in Garo.

Garo has been witnessing an immense growth in its printed literature lately. There has been an increase in the production of learning materials such as dictionaries, grammar and other text books, translated materials, newspapers, magazines and journals, novels, collection of short stories, folklores and myths, scholarly materials, and many important religious publications such as the Garo bible and the Garo hymnal. However, further research on the language itself has been slow – rather rare − but not non-existent.

Numbers

1. Sa

2. Gni

3. Gittam

4. Bri

5. Bonga

6. Dok

7. Sni

8. Chet

9. Sku

10. Chiking or chikung

11. Chi sa

12. Chi gni

13. Chi gittim

14. Chi bri

15. Chi bonga

16. Chi dok

17. Chi sni

18. Chi chet

19. Chi sku

20. Kol grik

Nouns

Garo is a SOV language, which means that the verbs will usually be placed at the end of a sentence. Any noun phrases will come before the verb phrases.

Casing

All nouns in Garo can be inflected for a variety of grammatical cases. Declension of a noun can be done by using specific suffixes:

| Case | Garo suffix | Example with Bol | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | — | Ia bol dal•gipa ong•a. | This tree is big. |

| Accusative | -ko | Anga bolko nika. | I see the tree. |

| Genitive | -ni | Bolni bijakrang ga•akenga. | The tree's leaves are falling. |

| Dative | -na | Anga bolna aganaha. | I talked to the tree. |

| Locative | -o/-chi (-chi is only used to refer to space; bolchi "In the tree" would be valid, but walchi "In the night" would not) | Bolo/Bolchi makre mangbonga ong•a. | There are five monkeys in the tree. |

| Instrumental | -chi | Anga ruachi bolko den•aha. | I cut the tree with an axe. |

| Comitative | -ming | Anga bolming tangaha. | I lived with the tree. |

Some nouns will naturally happen to have a vowel at the end of it. When declining the nouns into a non-nominative case, usually the final vowel should be removed: e.g. Do•o "Bird" will become Do•ni when declined into the genitive case.

Additionally, casing suffixes can also be combined. -o and -na combine to form -ona, which means "Towards" (Lative case). -o and -ni combine to form -oni, which means "From" (Ablative case). Example usages can be "Anga Turaoni Shillong-ona re•angaha", which means "I traveled from Tura to Shillong".

Pronouns

Garo has pronouns for first, second, and third person in both singular and plural, much like in English. Garo also considers clusivity and has two separate first-person plural pronouns for both "inclusive we" and "exclusive we". However, Garo does not consider grammatical gender, and has one pronoun for third person singular. The following table displays the subjective inflection of each pronoun (i.e. when the pronoun is used as subject).

| singular | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | anga | an•ching |

| inclusive | chinga | ||

| 2nd person | na•a | na•simang | |

| 3rd person | ua | uamang | |

Note that in written Garo, "Bia" is often replaced with "Ua", which literally means "That" in English.

In the Am•beng dialect, "An•ching" is "Na•ching", and "Na•simang" and "Uamang" are "Na•song" and "Bisong" respectively.

Prounouns can also be declined as other nouns. One exception is "Na•a". When declined, the stem noun becomes "Nang'". "Your" translated to Garo would be "Nang•ni"

Verbs

Verbs in Garo are only conjugated based on the grammatical tense of the action. There are three main conjugations:

| Tense | Garo suffix | Example with Cha•a | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past | -aha | Mi cha•aha. | ate rice. |

| Present | -a | Mi cha•a | eat rice. |

| Future | -gen | Mi cha•gen. | will eat rice. |

However, there are a diverse range of verb suffixes that can be added to Garo verbs. Some of these suffixes include:

- Imperative mood - The second-person imperative mood is indicated with the suffix -bo.

- "On•a" (To give) → "Angna iako on•bo" (Give me this)

- Yes–no questions - When adding the suffix -ma to the end of a verb, the clause becomes an interrogation.

- "Nika" (To see) → "Uako nikama?" (Do you see that?)

- Infinitive - Adding -na to a verb will conjugate it into its infinitive form.

- "Ring•a" (To sing) → "Anga ring•na namnika" (I like singing)

- Negation - To negate a verb, -ja will be added. Note that negating a verb in its future tense will yield -jawa, e.g. "Anga nikgen" (I will see) → "Anga nikjawa" (I will not see)

- "Namnika" (To like) → "Namnikja" (To not like, to hate)

- Progressive aspect - The progressive aspect can be indicated using -eng.

- "Anga kal•a" (I play) → "Anga kal•enga" (I am playing)

- Adjectives - Garo does not truly support adjectives. To modify a noun, a nominalised verb is used instead. Verb nominalising is done by using the suffix -gipa.

- "Dal•a" (To be big) → "Dal•gipa" (The thing that is big) → "Dal•gipa ro•ong" (The big rock)

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | p (pʰ) | t̪ (t̪ʰ) | t͡ɕ | k (kʰ) | ʔ | |

| voiced | b | d̪ | d͡ʑ | ɡ | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Fricative | s | h | |||||

| Tap | ɾ | ||||||

| Lateral | l | ||||||

| Approximant | w | j | |||||

- Voiceless stops /p, t̪, k/ are always aspirated in word-initial position as . In word-final position, they are heard as unreleased .

- /s/ is heard as an alveolo-palatal fricative when occurring before front vowel sounds.

- /ɾ/ is heard as a trill when occurring within consonant clusters.

- /j/ only occurs in diphthongs such as ⟨ai⟩, ⟨oi⟩, ⟨ui⟩. The ⟨j⟩ grapheme already represents /d͡ʑ/.

- /ʔ/ is represented by interpunct ⟨·⟩ or apostrophe ⟨ʼ⟩.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɯ / u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

The ⟨i⟩ grapheme represents both /i/ and /ɯ/. An ⟨-i-⟩ syllable that ends with a consonant other than /ʔ/ (not forming part of a consonant cluster) is pronounced , otherwise, it is pronounced .

While almost all other languages in the Bodo–Garo sub-family contrast between low and high tones, Garo is one of the sole exceptions. Wood writes that instead Garo seems to have substituted the tonal system by contrasting between syllables that end in a glottal stop and those that do not, with the glottal stop replacing the low tone.

See also

- Garo people

- Garo Hills

- Bible translations into the languages of Northeast India

- Department of Garo, North-Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus

References

- "Statement 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues - 2011". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- (Joseph and Burling 2006: 1)

- "A•Chik Tokbirim". Omniglot

- "Garo script". Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Marak, D. 2013. "Linguistic Ecology of Garo." In Singh, Shailendra Kumar (ed). Linguistic Ecology of Meghalaya. Guwahati: EBH Publishers. ISBN 978-93-80261-96-6

- Watre Ingty, Angela R. (2008). Garo morphology, a descriptive analysis. North-Eastern Hill University.

- Wood, Daniel Cody. 2008. An Initial Reconstruction of Proto-Boro-Garo. M.A. Thesis, University of Oregon. pg 22

- Burling, Robbins. 2003. The Language of the Modhupur Mandi, Volume 1. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

- SIL International. "Garo". Ethnologue, 2014

- Burling, Robbins and Joseph, U.V. 2006. A Comparative Phonology of Boro Garo Languages. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

- Breugel, Seino van. 2009. Atong-English Dictionary. Tura: Tura Book Room.

- Breugel, Seino van. 2014. A grammar of Atong. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

| Sal (Brahmaputran) languages | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boro–Garo |

| ||||||||

| Konyak (Northern Naga) |

| ||||||||

| Jingpho–Luish |

| ||||||||

| Languages of Northeast India | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Assam |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Manipur |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Meghalaya |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Mizoram | |||||||||||||||||

| Nagaland |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Sikkim | |||||||||||||||||

| Tripura |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Languages of India | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official languages |

| ||||||||||

| Major unofficial languages |

| ||||||||||