Medical condition

| Benzodiazepine use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benzodiazepine drug misuse |

| Specialty | Addiction Medicine, Psychiatry |

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

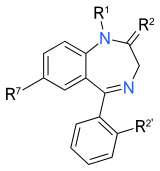

The core structure of benzodiazepines. "R" labels denote common locations of side chains, which give different benzodiazepines their unique properties. The core structure of benzodiazepines. "R" labels denote common locations of side chains, which give different benzodiazepines their unique properties. |

Benzodiazepine use disorder (BUD), also called misuse or abuse, is the use of benzodiazepines without a prescription and/or for recreational purposes, which poses risks of dependence, withdrawal and other long-term effects. Benzodiazepines are one of the more common prescription drugs used recreationally. When used recreationally benzodiazepines are usually administered orally but sometimes they are taken intranasally or intravenously. Recreational use produces effects similar to alcohol intoxication.

In tests in pentobarbital-trained rhesus monkeys benzodiazepines produced effects similar to barbiturates. In a 1991 study, triazolam had the highest self-administration rate in cocaine-trained baboons, among the five benzodiazepines examined: alprazolam, bromazepam, chlordiazepoxide, lorazepam, triazolam. A 1985 study found that triazolam and temazepam maintained higher rates of self-injection in both human and animal subjects compared to a variety of other benzodiazepines (others examined: diazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, flurazepam, alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, nitrazepam, flunitrazepam, bromazepam, and clorazepate). A 1991 study indicated that diazepam, in particular, had a greater abuse liability among people who were drug abusers than did many of the other benzodiazepines. Some of the available data also suggested that lorazepam and alprazolam are more diazepam-like in having relatively high abuse liability, while oxazepam, halazepam, and possibly chlordiazepoxide, are relatively low in this regard. A 1991–1993 British study found that the hypnotics flurazepam and temazepam were more toxic than average benzodiazepines in overdose. A 1995 study found that temazepam is more rapidly absorbed and oxazepam is more slowly absorbed than most other benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines have been abused both orally and intravenously. Different benzodiazepines have different abuse potential; the more rapid the increase in the plasma level following ingestion, the greater the intoxicating effect and the more open to abuse the drug becomes. The speed of onset of action of a particular benzodiazepine correlates well with the 'popularity' of that drug for abuse. The two most common reasons for preference were that a benzodiazepine was 'strong' and that it gave a good 'high'.

According to Dr. Chris Ford, former clinical director of Substance Misuse Management in General Practice, among drugs of abuse, benzodiazepines are often seen as the 'bad guys' by drug and alcohol workers. Illicit users of benzodiazepines have been found to take higher methadone doses, as well as showing more HIV/HCV risk-taking behavior, greater poly-drug use, higher levels of psychopathology and social dysfunction. However, there is only limited research into the adverse effects of benzodiazepines in drug misusers and further research is needed to demonstrate whether this is the result of cause or effect.

Signs and symptoms

See also: Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome and Benzodiazepine dependence

Sedative-hypnotics such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and the barbiturates are known for the severe physical dependence that they are capable of inducing which can result in severe withdrawal effects. This severe neuroadaptation is even more profound in high dose drug users and misusers. A high degree of tolerance often occurs in chronic benzodiazepine abusers due to the typically high doses they consume which can lead to a severe benzodiazepine dependence. The benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome seen in chronic high dose benzodiazepine abusers is similar to that seen in therapeutic low dose users but of a more severe nature. Extreme antisocial behaviors in obtaining continued supplies and severe drug-seeking behavior when withdrawals occur. The severity of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome has been described by one benzodiazepine drug misuser who stated that:

I'd rather withdraw off heroin any day. If I was withdrawing from benzos you could offer me a gram of heroin or just 20mg of diazepam and I'd take the diazepam every time – I've never been so frightened in my life.

Those who use benzodiazepines intermittently are less likely to develop a dependence and withdrawal symptoms upon dose reduction or cessation of benzodiazepines than those who use benzodiazepines on a daily basis.

Misuse of benzodiazepines is widespread amongst drug misusers; however, many of these people will not require withdrawal management as their use is often restricted to binges or occasional misuse. Benzodiazepine dependence when it occurs requires withdrawal treatment. There is little evidence of benefit from long-term substitution therapy of benzodiazepines, and conversely, there is growing evidence of the harm of long-term use of benzodiazepines, especially higher doses. Therefore, gradual reduction is recommended, titrated against withdrawal symptoms. For withdrawal purposes, stabilisation with a long-acting agent such as diazepam is recommended before commencing withdrawal. Chlordiazepoxide (Librium), a long-acting benzodiazepine, is gaining attention as an alternative to diazepam in substance abusers dependent on benzodiazepines due to its decreased abuse potential. In individuals dependent on benzodiazepines who have been using benzodiazepines long-term, taper regimens of 6–12 months have been recommended and found to be more successful. More rapid detoxifications e.g. of a month are not recommended as they lead to more severe withdrawal symptoms.

Tolerance leads to a reduction in GABA receptors and function; when benzodiazepines are reduced or stopped this leads to an unmasking of these compensatory changes in the nervous system with the appearance of physical and mental withdrawal effects such as anxiety, insomnia, autonomic hyperactivity and possibly seizures.

Common withdrawal symptoms

Include the following:

- Depression

- Shaking

- Feeling unreal

- Appetite loss

- Muscle twitching

- Severe and debilitating insomnia

- Memory loss

- Motor impairment

- Nausea

- Muscle pains

- Dizziness

- Apparent movement of still objects

- Feeling faint

- Noise sensitivity

- Light sensitivity

- Peculiar taste

- Pins and needles

- Touch sensitivity

- Sore eyes

- Hallucinations

- Smell sensitivity

All sedative-hypnotics, e.g. alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs have a similar mechanism of action, working on the GABAA receptor complex and are cross tolerant with each other and also have abuse potential. Use of prescription sedative-hypnotics—for example, the nonbenzodiazepine Z-drugs—often leads to a relapse back into substance misuse with one author stating this occurs in over a quarter of those who have achieved abstinence.

Background

Benzodiazepines are a commonly abused class of drugs, although there is debate as to whether certain benzodiazepines have higher abuse potential than others. In animal and human studies the abuse potential of benzodiazepines is classed as moderate in comparison to other drugs of abuse. Benzodiazepines are commonly abused by poly drug users, especially heroin addicts, alcoholics or amphetamine addicts when "coming down". but sometimes are misused in isolation as the primary drug of misuse. They can be misused to achieve the high that benzodiazepines produce or more commonly they are used to either enhance the effects of other CNS depressant drugs, to stave off withdrawal effects of other drugs or combat the effects of stimulants. As many as 30–50% of alcoholics are also benzodiazepine misusers. Drug abusers often abuse high doses or even therapeutic doses for long periods of time which makes serious benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms such as psychosis or convulsions more likely to occur during withdrawal.

Benzodiazepine abuse increases risk-taking behaviors such as unprotected sex and sharing of needles amongst intravenous abusers of benzodiazepines. Abuse is also associated with blackouts, memory loss, aggression, violence, and chaotic behavior associated with paranoia. There is little support for long-term maintenance of benzodiazepine abusers and thus a withdrawal regime is indicated when benzodiazepine abuse becomes a dependence. The main source of illicit benzodiazepines are diverted benzodiazepines obtained originally on prescription; other sources include thefts from pharmacies and pharmaceutical warehouses. Benzodiazepine abuse is steadily increasing and is now a major public health problem. Benzodiazepine abuse is mostly limited to individuals who abuse other drugs, i.e. poly-drug abusers. Most prescribed users do not abuse their medication, however, some high dose prescribed users do become involved with the illicit drug scene. Abuse of benzodiazepines occurs in a wide age range of people and includes teenagers and the old. The abuse potential or drug-liking effects appears to be dose related, with low doses of benzodiazepines having limited drug liking effects but higher doses increasing the abuse potential/drug-liking properties.

Health related complications

See also: Long-term effects of benzodiazepinesComplications of benzodiazepine abuse include drug-related deaths due to overdose especially in combination with other depressant drugs such as opioids. Other complications include: blackouts and memory loss, paranoia, violence and criminal behaviour, risk-taking sexual behaviour, foetal and neonatal risks if taken in pregnancy, dependence, withdrawal seizures and psychosis. Injection of the drug carries risk of: thrombophlebitis, deep vein thrombosis, deep and superficial abscesses, pulmonary microembolism, rhabdomyolysis, tissue necrosis, gangrene requiring amputation, hepatitis B and C, as well as blood borne infections such as HIV infection (caused by sharing injecting equipment). Long-term use of benzodiazepines can worsen pre-existing depression and anxiety and may potentially also cause dementia with impairments in recent and remote memory functions.

Use is widespread among amphetamine users, with those that use amphetamines and benzodiazepines having greater levels of mental health problems and social deterioration. Benzodiazepine injectors are almost four times more likely to inject using a shared needle than non-benzodiazepine-using injectors. It has been concluded in various studies that benzodiazepine use causes greater levels of risk and psycho-social dysfunction among drug misusers. Poly-drug users who also use benzodiazepines appear to engage in more frequent high-risk behaviors. Polydrug use involving benzodiazepines and alcohol can result in blackouts, increased risk-taking behaviour, and in severe cases seizures and overdose. Those who use stimulant and depressant drugs are more likely to report adverse reactions from stimulant use, more likely to be injecting stimulants and more likely to have been treated for a drug problem than those using stimulant but not depressant drugs.

Risk factors

See also: List of benzodiazepinesIndividuals with a substance abuse history are at an increased risk of misusing benzodiazepines.

Several (primary research) studies, even into the last decade, claimed that individuals with a history of familial abuse of alcohol or who are siblings or children of alcoholics appeared to respond differently to benzodiazepines than so called genetically healthy persons, with males experiencing increased euphoric effects and females having exaggerated responses to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines.

Whilst all benzodiazepines have abuse potential, certain characteristics increase the potential of particular benzodiazepines for abuse. Worldwide, diazepam is the benzodiazepine most frequently encountered by customs and law enforcement. Diazepam is available for very cheap in every country. These characteristics are chiefly practical ones—most especially, availability (often based on popular perception of 'dangerous' versus 'none dangerous' drugs) through prescribing physicians or illicit distributors. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic factors are also crucial in determining abuse potentials. A short elimination half-life and a rapid onset of action are characteristics which increase the abuse potential of a benzodiazepines. The following table provides the elimination half-life, approximate equivalent doses, speed of onset of action, and duration of behavioural effects.

| Drug Name | Common Brand Names* | Onset of action | Duration of action (h)** | Elimination Half-Life (h) | Approximate Equivalent Dose (PO)*** |

| Alprazolam | Xanax, Xanor, Tafil, Alprox, Niravam, Ksalol, Solanax | Intermediate | 3–5 | 11-13 | 0.5 mg |

| Chlordiazepoxide | Librium, Tropium, Risolid, Klopoxid | Intermediate | 4-6 | 5–30 hours | 25 mg |

| Clonazepam | Klonopin, Klonapin, Rivotril, Iktorivil | Intermediate | 10–12 | 18–50 hours | 0.5 mg |

| Clorazepate | Tranxene | Intermediate | 6-8 | 15 mg | |

| Diazepam | Valium, Apzepam, Stesolid, Vival, Apozepam, Hexalid, Valaxona | Fast | 1–6 | 20–100 hours | 10 mg |

| Etizolam**** | Etivan | Fast | 5-7 | 6-8 h | 1 mg |

| Estazolam | ProSom | Slow | 2–6 | 10–24 h | 2 mg |

| Flunitrazepam | Rohypnol, Fluscand, Flunipam, Ronal | Fast | 6–8 | 18–26 hours | 1 mg |

| Flurazepam | Dalmadorm, Dalmane | Fast | 7–10 | 20 mg | |

| Lorazepam | Ativan, Temesta, Lorabenz, Tavor | Intermediate | 2–6 | 10–20 hours | 1 mg |

| Midazolam | Dormicum, Versed, Hypnovel, Flormidal | Fast | 0.5–1 | 3 hours (1.8–6 hours) | 10 mg |

| Nitrazepam | Mogadon, Nitrosun, Epam, Alodorm, Insomin | Fast | 4-8 | 16–38 hours | 10 mg |

| Oxazepam | Seresta, Serax, Serenid, Serepax, Sobril, Oxascand, Alopam, Oxabenz, Oxapax | Slow | 4–6 | 4–15 hours | 30 mg |

| Prazepam | Lysanxia, Centrax | Intermediate | 6-9 | 36–200 hours | 20 mg |

| Quazepam | Doral | Slow | 6 | 39–120 hours | 20 mg |

| Temazepam | Restoril, Normison, Euhypnos, Tenox | Fast | 1-4 | 4–11 hours | 20 mg |

| Triazolam | Halcion, Rilamir | Fast | 0.5–1 | 2 hours | 0.25 mg |

*Not all trade names are listed. Click on the drug name to see a more comprehensive list.

**The duration of apparent action is usually considerably less than the half-life. With most benzodiazepines, noticeable effects usually wear off within a few hours. Nevertheless, as long as the drug is present it will exert subtle effects within the body. These effects may become apparent during continued use or may appear as withdrawal symptoms when dosage is reduced or the drug is stopped.

***Equivalent doses are based on clinical experience but may vary between individuals.

****Etizolam is not a true benzodiazepine but has similar chemistry, effects, and abuse potential.

Epidemiology

Little attention has focused on the degree that benzodiazepines are abused as a primary drug of choice, but they are frequently abused alongside other drugs of abuse, especially alcohol, stimulants and opiates. The benzodiazepine most commonly abused can vary from country to country and depends on factors including local popularity as well as which benzodiazepines are available. Nitrazepam for example is commonly abused in Nepal and the United Kingdom, whereas in the United States of America where nitrazepam is not available on prescription other benzodiazepines are more commonly abused. In the United Kingdom and Australia there have been epidemics of temazepam abuse. Particular problems with abuse of temazepam are often related to gel capsules being melted and injected and drug-related deaths. Injecting most benzodiazepines is dangerous because of their relative insolubility in water (with the exception of midazolam), leading to potentially serious adverse health consequences for users.

Benzodiazepines are a commonly misused class of drug. A study in Sweden found that benzodiazepines are the most common drug class of forged prescriptions in Sweden. Concentrations of benzodiazepines detected in impaired motor vehicle drivers often exceeding therapeutic doses have been reported in Sweden and in Northern Ireland. One of the hallmarks of problematic benzodiazepine drug misuse is escalation of dose. Most licit prescribed users of benzodiazepines do not escalate their dose of benzodiazepines.

Society and culture

Drug-related crime

See also: Drug-related crimeProblem benzodiazepine use can be associated with various deviant behaviors, including drug-related crime. In a survey of police detainees carried out by the Australian Government, both legal and illegal users of benzodiazepines were found to be more likely to have lived on the streets, less likely to have been in full-time work and more likely to have used heroin or methamphetamines in the past 30 days from the date of taking part in the survey. Benzodiazepine users were also more likely to be receiving illegal incomes and more likely to have been arrested or imprisoned in the previous year. Benzodiazepines were sometimes reported to be used alone, but most often formed part of a poly drug-using problem. Female users were more likely than men to be using heroin, whereas male users were more likely to report amphetamine use. Benzodiazepine users were more likely than non-users to claim government financial benefits and benzodiazepine users who were also poly-drug users were the most likely to be claiming government financial benefits. Those who reported using benzodiazepines alone were found to be in the mid-range when compared to other drug using patterns in terms of property crimes and criminal breaches. Of the detainees reporting benzodiazepine use, one in five reported injection use, mostly of illicit temazepam, with some who reported injecting prescribed benzodiazepines. The injection was a concern in this survey due to increased health risks. The main problems highlighted in this survey were concerns of dependence, the potential for overdose of benzodiazepines in combination with opiates and the health problems associated with injection of benzodiazepines.

Benzodiazepines are also sometimes used for drug facilitated sexual assaults and robbery, however, alcohol remains the most common drug involved in drug facilitated assaults. The muscle relaxant, disinhibiting and amnesia producing effects of benzodiazepines are the pharmacological properties which make these drugs effective in drug-facilitated crimes. Serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer admitted to using triazolam (Halcion), and occasionally temazepam (Restoril), in order to sedate his victims prior to murdering them.

In a 2017 publication, an analysis of the blood samples of 22 victims of drug-facilitated robberies in Bangladesh revealed that criminals use different mixtures of Benzodiazepines including Lorazepam, Midazolam, Diazepam and Nordiazepam to immobilize and then rob their victims.

Drug regulation and enforcement

Europe

Temazepam abuse and seizures have been falling in the UK probably due to its reclassification as Schedule 3 controlled drug with tighter prescribing restrictions and the resultant reduction in availability. A total of 2.75 million temazepam capsules were seized in the Netherlands by authorities between 1996 and 1999. In Northern Ireland statistics of individuals attending drug addiction treatment centers found that benzodiazepines were the 2nd most commonly reported main problem drugs (31 percent of attendees). Cannabis was the top with 35 percent of individuals reporting it as their main problem drug. The statistics showed that treatment for benzodiazepines as the main problematic drug had more than doubled from the previous year and was a growing problem in Northern Ireland.

Oceania

Benzodiazepines are common drugs of abuse in Australia and New Zealand, particularly among those who may also be using other illicit drugs. The intravenous use of temazepam poses the greatest threat to those who misuse benzodiazepines. Simultaneous consumption of temazepam with heroin is a potential risk factor of overdose. An Australian study of non-fatal heroin overdoses noted that 26% of heroin users had consumed temazepam at the time of their overdose. This is consistent with an NSW investigation of coronial files from 1992. Temazepam was found in 26% of heroin-related deaths. Temazepam, including tablet formulations, are used intravenously. In an Australian study of 210 heroin users who used temazepam, 48% had injected it. Although abuse of benzodiazepines has decreased over the past few years, temazepam continues to be a major drug of abuse in Australia. In certain states like Victoria and Queensland, temazepam accounts for most benzodiazepine sought by forgery of prescriptions and through pharmacy burglary. Darke, Ross & Hall found that different benzodiazepines have different abuse potential. The more rapid the increase in the plasma level following ingestion, the greater the intoxicating effect and the more open to abuse the drug becomes. The speed of onset of action of a particular benzodiazepine correlates well with the 'popularity' of that drug for abuse. The two most common reasons for preference for a benzodiazepine were that it was the 'strongest' and that it gave a good 'high'.

North America

The most frequently abused of the benzodiazepines in both the United States and Canada are alprazolam, clonazepam, lorazepam and diazepam. In Canada, bromazepam is marketed and is a highly effective anxiolytic, muscle-relaxant, and sedative. Bromazepam has shown itself to be at least as effective as alprazolam as anxiolytic, and a superior sedative.

East and Southeast Asia

The Central Narcotics Bureau of Singapore seized 94,200 nimetazepam tablets in 2003. This is the largest nimetazepam seizure recorded since nimetazepam became a controlled drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1992. In Singapore nimetazepam is a Class C controlled drug.

In Hong Kong abuse of prescription medicinal preparations continued in 2006 and seizures of midazolam (120,611 tablets), nimetazepam/nitrazepam (17,457 tablets), triazolam (1,071 tablets), diazepam (48,923 tablets) and chlordiazepoxide (5,853 tablets) were made. Heroin addicts used such tablets (crushed and mixed with heroin) to prolong the effect of the narcotic and ease withdrawal symptoms.

See also

- Drug abuse

- Benzodiazepine overdose

- Effects of long-term benzodiazepine use

- Drug facilitated sexual assault

References

- "Benzodiazepine dependence: reduce the risk". NPS MedicineWise. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Tyrer, P.; Silk, K. R., eds. (2008). "Treatment of Sedative-Hypnotic Dependence". Cambridge Textbook of Effective Treatments in Psychiatry (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-521-84228-0.

- ^ Griffiths, R. R.; Johnson, M. W. (2005). "Relative Abuse Liability of Hypnotic Drugs: A Conceptual Framework and Algorithm for Differentiating among Compounds" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (Suppl 9): 31–41. PMID 16336040. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Sheehan, M. F.; Sheehan, D. V.; Torres, A.; Coppola, A.; Francis, E. (1991). "Snorting Benzodiazepines". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 17 (4): 457–468. doi:10.3109/00952999109001605. PMID 1684083.

- Woolverton, W. L.; Nader, M. A. (December 1995). "Effects of several benzodiazepines, alone and in combination with flumazenil, in rhesus monkeys trained to discriminate pentobarbital from saline". Psychopharmacology. 122 (3): 230–236. doi:10.1007/BF02246544. PMID 8748392. S2CID 24836734.

- Griffiths, R. R.; Lamb, R. J.; Sannerud, C. A.; Ator, N. A.; Brady, J. V. (1991). "Self-Injection of Barbiturates, Benzodiazepines and other Sedative-Anxiolytics in Baboons". Psychopharmacology. 103 (2): 154–161. doi:10.1007/BF02244196. PMID 1674158. S2CID 30449419.

- GRIFFITHS, Roland R.; RICHARD J. LAMB; NANCY A. ATOR; JOHN D. ROACHE; JOSEPH V. BRADY (1985). "Relative Abuse Liability of Triazolam: Experimental Assessment in Animals and Humans" (PDF). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 9 (1): 133–151. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.410.6027. doi:10.1016/0149-7634(85)90039-9. PMID 2858078. S2CID 17366074. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ Griffiths, R. R.; Wolf, B. (August 1990). "Relative Abuse Liability of different Benzodiazepines in Drug Abusers". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10 (4): 237–243. doi:10.1097/00004714-199008000-00002. PMID 1981067. S2CID 28209526.

- Serfaty, M.; Masterton, G. (September 1993). "Fatal poisonings attributed to benzodiazepines in Britain during the 1980s". British Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (3): 386–393. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.3.386. PMID 8104653. S2CID 46001278.

- Buckley, N. A.; Dawson, A. H.; Whyte, I. M.; O'Connell, D. L. (1995). "Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose". British Medical Journal. 310 (6974): 219–21. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6974.219. PMC 2548618. PMID 7866122.

- ^ Australian Government; Medical Board (2006). "ACT MEDICAL BOARD – STANDARDS STATEMENT – PRESCRIBING OF BENZODIAZEPINES" (PDF). Australia: ACT medical board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- Chris Ford (2009). "What is possible with benzodiazepines". UK: Exchange Supplies, 2009 National Drug Treatment Conference. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010.

- Ray Baker. "Dr Ray Baker's Article on Addiction: Benzodiazepines in Particular". Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ Ashton, C. H. (2002). "BENZODIAZEPINE ABUSE". Drugs and Dependence. Harwood Academic Publishers. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (2007). "Drug misuse and dependence – UK guidelines on clinical management" (PDF). United Kingdom: Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012.

- ^ Karch, S. B. (2006). Drug Abuse Handbook (2nd ed.). USA: CRC Press. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-8493-1690-6.

- ^ Gitlow, S. (2006). Substance Use Disorders: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. pp. 103–121. ISBN 978-0-7817-6998-3.

- ^ Longo, L. P.; Johnson, B. (April 2000). "Addiction: Part I. Benzodiazepines – Side effects, abuse risk and alternatives". American Family Physician. 61 (7): 2121–2128. PMID 10779253. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- Dart, R. C. (2003). Medical Toxicology (3rd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 819. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- Griffiths, R. R.; Weerts, E. M. (November 1997). "Benzodiazepine Self-Administration in Humans and Laboratory Animals – Implications for Problems of Long-Term Use and Abuse". Psychopharmacology. 134 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1007/s002130050422. PMID 9399364. S2CID 23960995. Archived from the original on 12 January 2002. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- Jones, AW; Holmgren A (April 2013). "Amphetamine abuse in Sweden: subject demographics, changes in blood concentrations over time, and the types of coingested substances". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 33 (2): 248–252. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182870310. PMID 23422398. S2CID 40680580.

- Caan, W.; de Belleroche, J., eds. (2002). "Benzodiazepine Abuse". Drink, Drugs and Dependence: From Science to Clinical Practice (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 197–211. ISBN 978-0-415-27891-1.

- Galanter, M.; Kleber, H. D. (2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- Darke, S.; Ross, J.; Cohen, J. (1994). "The Use of Benzodiazepines among Regular Amphetamine Users". Addiction. 89 (12): 1683–1690. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03769.x. PMID 7866252.

- Bright, Joanna K; Martin, AJ; Richards, Monica; Morie, Marie (16 December 2022). "The Benzo Research Project: An evaluation of recreational benzodiazepine use amongst UK young people (18-25)". Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7813470.

- Williamson, S.; Gossop, M.; Powis, B.; Griffiths, P.; Fountain, J.; Strang, J. (1997). "Adverse effects of stimulant drugs in a community sample of drug users". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 44 (2–3): 87–94. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(96)01324-5. PMID 9088780.

- Hoffmann–La Roche. "Mogadon". RxMed. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Ciraulo, D. A.; Barnhill, J. G.; Greenblatt, D. J.; Shader, R. I.; Ciraulo, A. M.; Tarmey, M. F.; Molloy, M. A.; Foti, M. E. (September 1988). "Abuse liability and clinical pharmacokinetics of alprazolam in alcoholic men". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 49 (9): 333–337. PMID 3417618.

- Ciraulo, D. A.; Sarid-Segal, O.; Knapp, C.; Ciraulo, A. M.; Greenblatt, D. J.; Shader, R. I. (July 1996). "Liability to alprazolam abuse in daughters of alcoholics". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 153 (7): 956–958. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.7.956. PMID 8659624.

- Evans, S. M.; Levin, F. R.; Fischman, M. W. (June 2000). "Increased sensitivity to alprazolam in females with a paternal history of alcoholism". Psychopharmacology. 150 (2): 150–162. doi:10.1007/s002130000421. PMID 10907668. S2CID 10076182.

- Streeter, C. C.; Ciraulo, D. A.; Harris, G. J.; Kaufman, M. J.; Lewis, R. F.; Knapp, C. M.; Ciraulo, A. M.; Maas, L. C.; Ungeheuer, M.; Renshaw, P. F.; Szulewski, S. (May 1998). "Functional magnetic resonance imaging of alprazolam-induced changes in humans with familial alcoholism". Psychiatry Research. 82 (2): 69–82. doi:10.1016/S0925-4927(98)00009-2. PMID 9754450. S2CID 26676149.

- Galanter, M.; Kleber, H. D. (1 July 2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States of America: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- Shader, R. I.; Greenblatt, D. J. (1981). "The use of benzodiazepines in clinical practice". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 11 (Suppl 1): 5S – 9S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01832.x. PMC 1401641. PMID 6133535.

- "benzo.org.uk : Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". benzo.org.uk.

- Chatterjee, A.; Uprety, L.; Chapagain, M.; Kafle, K. (1996). "Drug abuse in Nepal: a rapid assessment study". Bulletin on Narcotics. 48 (1–2): 11–33. PMID 9839033.

- Garretty, D. J.; Wolff, K.; Hay, A. W.; Raistrick, D. (January 1997). "Benzodiazepine misuse by drug addicts". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 34 (Pt 1): 68–73. doi:10.1177/000456329703400110. PMID 9022890. S2CID 42665843.

- Wilce, H. (June 2004). "Temazepam capsules: What was the problem?". Australian Prescriber. 27 (3): 58–59. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2004.053.

- Ashton, H. (2002). "Benzodiazepine Abuse". Drugs and Dependence. London & New York: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Hammersley, R.; Cassidy, M. T.; Oliver, J. (1995). "Drugs associated with drug-related deaths in Edinburgh and Glasgow, November 1990 to October 1992". Addiction. 90 (7): 959–965. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9079598.x. PMID 7663317.

- Wang, E.C.; Chew, F. S. (2006). "MR Findings of Alprazolam Injection into the Femoral Artery with Microembolization and Rhabdomyolysis". Radiology Case Reports. 1 (3): 99–102. doi:10.2484/rcr.v1i3.33. PMC 4891562. PMID 27298694. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008.

- "DB00404 (Alprazolam)". Canada: DrugBank. 26 August 2008.

- Bergman, U.; Dahl-Puustinen, M. L. (1989). "Use of prescription forgeries in a drug abuse surveillance network". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (6): 621–623. doi:10.1007/BF00637747. PMID 2776820. S2CID 19770310.

- Jones, A. W.; Holmgren, A.; Kugelberg, F. C. (April 2007). "Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results". Therapeutic Drug Monitor. 29 (2): 248–260. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. PMID 17417081. S2CID 25511804.

- Cosbey, S. H. (December 1986). "Drugs and the impaired driver in Northern Ireland: an analytical survey". Forensic Science International. 32 (4): 245–58. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(86)90201-X. PMID 3804143.

- Lader, M. H. (1999). "Limitations on the use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and insomnia: are they justified?". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 9 (Suppl 6): S399–405. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00051-6. PMID 10622686. S2CID 43443180.

- Loxley, W. (2007). Benzodiazepine use and harms among police detainees in Australia (PDF). Canberra, A.C.T.: Australian Institute of Criminology. ISBN 978-1-921185-39-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2009.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Schwartz, R. H.; Milteer, R.; LeBeau, M. A. (June 2000). "Drug-facilitated sexual assault ('date rape')". Southern Medical Journal. 93 (6): 558–61. doi:10.1097/00007611-200093060-00002. PMID 10881768.

- Goullé, J. P.; Anger, J. P. (April 2004). "Drug-facilitated robbery or sexual assault: problems associated with amnesia". Therapeutical Drug Monitor. 26 (2): 206–210. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00021. PMID 15228166. S2CID 28052263.

- Kottler, Jeffrey (2010). Duped: Lies and Deception in Psychotherapy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87624-7.

- Ariful, Basher; Abul, Faiz, M; M, Arif, Syed; MAK, Khandaker; Ulrich, Kuch; SW, Toennes (20 June 2017). "Toxicological Screening of Drug Facilitated Crime among Travelers in Dhaka, Bangladesh". Asia Pacific Journal of Medical Toxicology. 6 (2). doi:10.22038/apjmt.2017.8949. ISSN 2322-2611.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Scottish Government (3 June 2008). "Statistical Bulletin – Drug Seizures by Scottish Police Forces, 2005/2006 and 2006/2007" (PDF). Crime and Justice Series. Scotland: scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- INCB (January 1999). "Operation of the international drug control system" (PDF). incb.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Northern Ireland Government (October 2008). "Statistics from the Northern Ireland Drug Misuse Database: 1 April 2007 – 31 March 2008" (PDF). Northern Ireland: Department of Health and Social Services and Public Safety.

- United States Government; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2006). "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- Central Narcotics Bureau; Singapore Government (2003). "Drug Situation Report 2003". Singapore: cnb.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Hong Kong Government. "Suppression of Illicit Trafficking and Manufacturing" (PDF). Hong Kong: nd.gov.hk. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Psychoactive substance-related disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||

| Combined substance use |

| ||||

| Alcohol |

| ||||

| Caffeine | |||||

| Cannabis | |||||

| Cocaine | |||||

| Hallucinogen | |||||

| Nicotine | |||||

| Opioids |

| ||||

| Sedative / hypnotic | |||||

| Stimulants | |||||

| Volatile solvent | |||||

| Related | |||||

| Unnecessary health care | |

|---|---|

| Causes | |

| Overused health care | |

| Tools and situations | |

| Works about unnecessary health care | |