| Part of a series of articles about | ||||||

| Calculus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Differential

|

||||||

Integral

|

||||||

Series

|

||||||

Vector

|

||||||

Multivariable

|

||||||

|

Advanced |

||||||

| Specialized | ||||||

| Miscellanea | ||||||

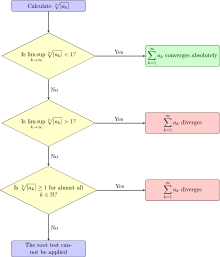

In mathematics, the root test is a criterion for the convergence (a convergence test) of an infinite series. It depends on the quantity

where are the terms of the series, and states that the series converges absolutely if this quantity is less than one, but diverges if it is greater than one. It is particularly useful in connection with power series.

Root test explanation

The root test was developed first by Augustin-Louis Cauchy who published it in his textbook Cours d'analyse (1821). Thus, it is sometimes known as the Cauchy root test or Cauchy's radical test. For a series

the root test uses the number

where "lim sup" denotes the limit superior, possibly +∞. Note that if

converges then it equals C and may be used in the root test instead.

The root test states that:

- if C < 1 then the series converges absolutely,

- if C > 1 then the series diverges,

- if C = 1 and the limit approaches strictly from above then the series diverges,

- otherwise the test is inconclusive (the series may diverge, converge absolutely or converge conditionally).

There are some series for which C = 1 and the series converges, e.g. , and there are others for which C = 1 and the series diverges, e.g. .

Application to power series

This test can be used with a power series

where the coefficients cn, and the center p are complex numbers and the argument z is a complex variable.

The terms of this series would then be given by an = cn(z − p). One then applies the root test to the an as above. Note that sometimes a series like this is called a power series "around p", because the radius of convergence is the radius R of the largest interval or disc centred at p such that the series will converge for all points z strictly in the interior (convergence on the boundary of the interval or disc generally has to be checked separately).

A corollary of the root test applied to a power series is the Cauchy–Hadamard theorem: the radius of convergence is exactly taking care that we really mean ∞ if the denominator is 0.

Proof

The proof of the convergence of a series Σan is an application of the comparison test.

If for all n ≥ N (N some fixed natural number) we have , then . Since the geometric series converges so does by the comparison test. Hence Σan converges absolutely.

If for infinitely many n, then an fails to converge to 0, hence the series is divergent.

Proof of corollary: For a power series Σan = Σcn(z − p), we see by the above that the series converges if there exists an N such that for all n ≥ N we have

equivalent to

for all n ≥ N, which implies that in order for the series to converge we must have for all sufficiently large n. This is equivalent to saying

so Now the only other place where convergence is possible is when

(since points > 1 will diverge) and this will not change the radius of convergence since these are just the points lying on the boundary of the interval or disc, so

Examples

Example 1:

Applying the root test and using the fact that

Since the series diverges.

Example 2:

The root test shows convergence because

This example shows how the root test is stronger than the ratio test. The ratio test is inconclusive for this series as if is even, while if is odd, , therefore the limit does not exist.

Root tests hierarchy

Root tests hierarchy is built similarly to the ratio tests hierarchy (see Section 4.1 of ratio test, and more specifically Subsection 4.1.4 there).

For a series with positive terms we have the following tests for convergence/divergence.

Let be an integer, and let denote the th iterate of natural logarithm, i.e. and for any , .

Suppose that , when is large, can be presented in the form

(The empty sum is assumed to be 0.)

- The series converges, if

- The series diverges, if

- Otherwise, the test is inconclusive.

Proof

Since , then we have

From this,

From Taylor's expansion applied to the right-hand side, we obtain:

Hence,

(The empty product is set to 1.)

The final result follows from the integral test for convergence.

See also

References

- Bottazzini, Umberto (1986), The Higher Calculus: A History of Real and Complex Analysis from Euler to Weierstrass, Springer-Verlag, pp. 116–117, ISBN 978-0-387-96302-0. Translated from the Italian by Warren Van Egmond.

- Briggs, William; Cochrane, Lyle (2011). Calculus: Early Transcendentals. Addison Wesley. p. 571.

- Abramov, Vyacheslav M. (2022). "Necessary and sufficient conditions for the convergence of positive series" (PDF). Journal of Classical Analysis. 19 (2): 117--125. arXiv:2104.01702. doi:10.7153/jca-2022-19-09.

- Bourchtein, Ludmila; Bourchtein, Andrei; Nornberg, Gabrielle; Venzke, Cristiane (2012). "A hierarchy of convergence tests related to Cauchy's test" (PDF). International Journal of Mathematical Analysis. 6 (37--40): 1847--1869.

- Knopp, Konrad (1956). "§ 3.2". Infinite Sequences and Series. Dover publications, Inc., New York. ISBN 0-486-60153-6.

- Whittaker, E. T. & Watson, G. N. (1963). "§ 2.35". A Course in Modern Analysis (fourth ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58807-3.

This article incorporates material from Proof of Cauchy's root test on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

| Calculus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precalculus | |||||

| Limits | |||||

| Differential calculus |

| ||||

| Integral calculus | |||||

| Vector calculus |

| ||||

| Multivariable calculus | |||||

| Sequences and series |

| ||||

| Special functions and numbers | |||||

| History of calculus | |||||

| Lists |

| ||||

| Miscellaneous topics |

| ||||

are the terms of the series, and states that the series converges absolutely if this quantity is less than one, but diverges if it is greater than one. It is particularly useful in connection with

are the terms of the series, and states that the series converges absolutely if this quantity is less than one, but diverges if it is greater than one. It is particularly useful in connection with

, and there are others for which C = 1 and the series diverges, e.g.

, and there are others for which C = 1 and the series diverges, e.g.  .

.

taking care that we really mean ∞ if the denominator is 0.

taking care that we really mean ∞ if the denominator is 0.

, then

, then  . Since the

. Since the  converges so does

converges so does  by the comparison test. Hence Σan converges absolutely.

by the comparison test. Hence Σan converges absolutely.

for infinitely many n, then an fails to converge to 0, hence the series is divergent.

for infinitely many n, then an fails to converge to 0, hence the series is divergent.

for all sufficiently large n. This is equivalent to saying

for all sufficiently large n. This is equivalent to saying

Now the only other place where convergence is possible is when

Now the only other place where convergence is possible is when

the series diverges.

the series diverges.

is even,

is even,  while if

while if  , therefore the limit

, therefore the limit  does not exist.

does not exist.

be an integer, and let

be an integer, and let  denote the

denote the  th

th  and for any

and for any  ,

,

.

.

, when

, when

, then we have

, then we have