| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Stellar corona" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A corona (pl.: coronas or coronae) is the outermost layer of a star's atmosphere. It is a hot but relatively dim region of plasma populated by intermittent coronal structures known as solar prominences or filaments.

The Sun's corona lies above the chromosphere and extends millions of kilometres into outer space. Coronal light is typically obscured by diffuse sky radiation and glare from the solar disk, but can be easily seen by the naked eye during a total solar eclipse or with a specialized coronagraph. Spectroscopic measurements indicate strong ionization in the corona and a plasma temperature in excess of 1000000 kelvins, much hotter than the surface of the Sun, known as the photosphere.

Corona (Latin for 'crown') is, in turn, derived from Ancient Greek κορώνη (korṓnē) 'garland, wreath'.

History

In 1724, French-Italian astronomer Giacomo F. Maraldi recognized that the aura visible during a solar eclipse belongs to the Sun, not to the Moon. In 1809, Spanish astronomer José Joaquín de Ferrer coined the term 'corona'. Based on his own observations of the 1806 solar eclipse at Kinderhook (New York), de Ferrer also proposed that the corona was part of the Sun and not of the Moon. English astronomer Norman Lockyer identified the first element unknown on Earth in the Sun's chromosphere, which was called helium (from Greek helios 'sun'). French astronomer Jules Jenssen noted, after comparing his readings between the 1871 and 1878 eclipses, that the size and shape of the corona changes with the sunspot cycle. In 1930, Bernard Lyot invented the "coronograph" (now "coronagraph"), which allows viewing the corona without a total eclipse. In 1952, American astronomer Eugene Parker proposed that the solar corona might be heated by myriad tiny 'nanoflares', miniature brightenings resembling solar flares that would occur all over the surface of the Sun.

Historical theories

The high temperature of the Sun's corona gives it unusual spectral features, which led some in the 19th century to suggest that it contained a previously unknown element, "coronium". Instead, these spectral features have since been explained by highly ionized iron (Fe-XIV, or Fe). Bengt Edlén, following the work of Walter Grotrian in 1939, first identified the coronal spectral lines in 1940 (observed since 1869) as transitions from low-lying metastable levels of the ground configuration of highly ionised metals (the green Fe-XIV line from Fe at 5303Å, but also the red Fe-X line from Fe at 6374Å).

Observable components

The solar corona has three recognized, and distinct, sources of light that occupy the same volume: the "F-corona" (for "Fraunhofer"), the "K-corona" (for "Kontinuierlich"), and the "E-corona" (for "emission").

The "F-corona" is named for the Fraunhofer spectrum of absorption lines in ordinary sunlight, which are preserved by reflection off small material objects. The F-corona is faint near the Sun itself, but drops in brightness only gradually far from the Sun, extending far across the sky and becoming the zodiacal light. The F-corona is recognized to arise from small dust grains orbiting the Sun; these form a tenuous cloud that extends through much of the solar system.

The "K-corona" is named for the fact that its spectrum is a continuum, with no major spectral features. It is sunlight that is Thomson-scattered by free electrons in the hot plasma of the Sun's outer atmosphere. The continuum nature of the spectrum arises from Doppler broadening of the Sun's Fraunhofer absorption lines in the reference frame of the (hot and therefore fast-moving) electrons. Although the K-corona is a phenomenon of the electrons in the plasma, the term is frequently used to describe the plasma itself (as distinct from the dust that gives rise to the F-corona).

The "E-corona" is the component of the corona with an emission-line spectrum, either inside or outside the wavelength band of visible light. It is a phenomenon of the ion component of the plasma, as individual ions are excited by collision with other ions or electrons, or by absorption of ultraviolet light from the Sun.

Physical features

The Sun's corona is much hotter (by a factor from 150 to 450) than the visible surface of the Sun: the corona's temperature is 1 to 3 million kelvin compared to the photosphere's average temperature – around 5800kelvin. The corona is far less dense than the photosphere, and produces about one-millionth as much visible light. The corona is separated from the photosphere by the relatively shallow chromosphere. The exact mechanism by which the corona is heated is still the subject of some debate, but likely possibilities include episodic energy releases from the pervasive magnetic field and magnetohydrodynamic waves from below. The outer edges of the Sun's corona are constantly being transported away, creating the "open" magnetic flux entrained in the solar wind.

The corona is not always evenly distributed across the surface of the Sun. During periods of quiet, the corona is more or less confined to the equatorial regions, with coronal holes covering the polar regions. However, during the Sun's active periods, the corona is evenly distributed over the equatorial and polar regions, though it is most prominent in areas with sunspot activity. The solar cycle spans approximately 11 years, from one solar minimum to the following minimum. Since the solar magnetic field is continually wound up due to the faster rotation of mass at the Sun's equator (differential rotation), sunspot activity is more pronounced at solar maximum where the magnetic field is more twisted. Associated with sunspots are coronal loops, loops of magnetic flux, upwelling from the solar interior. The magnetic flux pushes the hotter photosphere aside, exposing the cooler plasma below, thus creating the relatively dark sun spots.

High-resolution X-ray images of the Sun's corona photographed by Skylab in 1973, by Yohkoh in 1991–2001, and by subsequent space-based instruments revealed the structure of the corona to be quite varied and complex, leading astronomers to classify various zones on the coronal disc. Astronomers usually distinguish several regions, as described below.

Active regions

Main article: Active regionActive regions are ensembles of loop structures connecting points of opposite magnetic polarity in the photosphere, the so-called coronal loops. They generally distribute in two zones of activity, which are parallel to the solar equator. The average temperature is between two and four million kelvin, while the density goes from 10 to 10 particles per cubic centimetre.

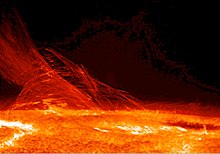

Active regions involve all the phenomena directly linked to the magnetic field, which occur at different heights above the Sun's surface: sunspots and faculae occur in the photosphere; spicules, Hα filaments and plages in the chromosphere; prominences in the chromosphere and transition region; and flares and coronal mass ejections (CME) happen in the corona and chromosphere. If flares are very violent, they can also perturb the photosphere and generate a Moreton wave. On the contrary, quiescent prominences are large, cool, dense structures which are observed as dark, "snake-like" Hα ribbons (appearing like filaments) on the solar disc. Their temperature is about 5000–8000K, and so they are usually considered as chromospheric features.

In 2013, images from the High Resolution Coronal Imager revealed never-before-seen "magnetic braids" of plasma within the outer layers of these active regions.

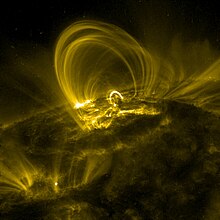

Coronal loops

Main article: Coronal loop

Coronal loops are the basic structures of the magnetic solar corona. These loops are the closed-magnetic flux cousins of the open-magnetic flux that can be found in coronal holes and the solar wind. Loops of magnetic flux well up from the solar body and fill with hot solar plasma. Due to the heightened magnetic activity in these coronal loop regions, coronal loops can often be the precursor to solar flares and CMEs.

The solar plasma that feeds these structures is heated from under 6000K to well over 10 K from the photosphere, through the transition region, and into the corona. Often, the solar plasma will fill these loops from one point and drain to another, called foot points (siphon flow due to a pressure difference, or asymmetric flow due to some other driver).

When the plasma rises from the foot points towards the loop top, as always occurs during the initial phase of a compact flare, it is defined as chromospheric evaporation. When the plasma rapidly cools and falls toward the photosphere, it is called chromospheric condensation. There may also be symmetric flow from both loop foot points, causing a build-up of mass in the loop structure. The plasma may cool rapidly in this region (for a thermal instability), its dark filaments obvious against the solar disk or prominences off the Sun's limb.

Coronal loops may have lifetimes in the order of seconds (in the case of flare events), minutes, hours or days. Where there is a balance in loop energy sources and sinks, coronal loops can last for long periods of time and are known as steady state or quiescent coronal loops (example).

Coronal loops are very important to our understanding of the current coronal heating problem. Coronal loops are highly radiating sources of plasma and are therefore easy to observe by instruments such as TRACE. An explanation of the coronal heating problem remains as these structures are being observed remotely, where many ambiguities are present (i.e., radiation contributions along the line-of-sight propagation). In-situ measurements are required before a definitive answer can be determined, but due to the high plasma temperatures in the corona, in-situ measurements are, at present, impossible. The next mission of the NASA Parker Solar Probe will approach the Sun very closely, allowing more direct observations.

Large-scale structures

Large-scale structures are very long arcs which can cover over a quarter of the solar disk but contain plasma less dense than in the coronal loops of the active regions.

They were first detected in the June 8, 1968, flare observation during a rocket flight.

The large-scale structure of the corona changes over the 11-year solar cycle and becomes particularly simple during the minimum period, when the magnetic field of the Sun is almost similar to a dipolar configuration (plus a quadrupolar component).

Interconnections of active regions

The interconnections of active regions are arcs connecting zones of opposite magnetic field, of different active regions. Significant variations of these structures are often seen after a flare.

Some other features of this kind are helmet streamers – large, cap-like coronal structures with long, pointed peaks that usually overlie sunspots and active regions. Coronal streamers are considered to be sources of the slow solar wind.

Filament cavities

Filament cavities are zones which look dark in the X-rays and are above the regions where Hα filaments are observed in the chromosphere. They were first observed in the two 1970 rocket flights which also detected coronal holes.

Filament cavities are cooler clouds of plasma suspended above the Sun's surface by magnetic forces. The regions of intense magnetic field look dark in images because they are empty of hot plasma. In fact, the sum of the magnetic pressure and plasma pressure must be constant everywhere on the heliosphere in order to have an equilibrium configuration: where the magnetic field is higher, the plasma must be cooler or less dense. The plasma pressure can be calculated by the state equation of a perfect gas: , where is the particle number density, the Boltzmann constant and the plasma temperature. It is evident from the equation that the plasma pressure lowers when the plasma temperature decreases with respect to the surrounding regions or when the zone of intense magnetic field empties. The same physical effect renders sunspots apparently dark in the photosphere.

Bright points

Bright points are small active regions found on the solar disk. X-ray bright points were first detected on April 8, 1969, during a rocket flight.

The fraction of the solar surface covered by bright points varies with the solar cycle. They are associated with small bipolar regions of the magnetic field. Their average temperature ranges from 1.1 MK to 3.4 MK. The variations in temperature are often correlated with changes in the X-ray emission.

Coronal holes

Main article: Coronal holeCoronal holes are unipolar regions which look dark in the X-rays since they do not emit much radiation. These are wide zones of the Sun where the magnetic field is unipolar and opens towards the interplanetary space. The high speed solar wind arises mainly from these regions.

In the UV images of the coronal holes, some small structures, similar to elongated bubbles, are often seen as they were suspended in the solar wind. These are the coronal plumes. More precisely, they are long thin streamers that project outward from the Sun's north and south poles.

The quiet Sun

The solar regions which are not part of active regions and coronal holes are commonly identified as the quiet Sun.

The equatorial region has a faster rotation speed than the polar zones. The result of the Sun's differential rotation is that the active regions always arise in two bands parallel to the equator and their extension increases during the periods of maximum of the solar cycle, while they almost disappear during each minimum. Therefore, the quiet Sun always coincides with the equatorial zone and its surface is less active during the maximum of the solar cycle. Approaching the minimum of the solar cycle (also named butterfly cycle), the extension of the quiet Sun increases until it covers the whole disk surface excluding some bright points on the hemisphere and the poles, where there are coronal holes.

Alfvén surface

Main article: Alfvén surfaceThe Alfvén surface is the boundary separating the corona from the solar wind defined as where the coronal plasma's Alfvén speed and the large-scale solar wind speed are equal.

Researchers were unsure exactly where the Alfvén critical surface of the Sun lay. Based on remote images of the corona, estimates had put it somewhere between 10 and 20 solar radii from the surface of the Sun. On April 28, 2021, during its eighth flyby of the Sun, NASA's Parker Solar Probe encountered the specific magnetic and particle conditions at 18.8 solar radii that indicated that it penetrated the Alfvén surface.

Variability of the corona

A portrait, as diversified as the one already pointed out for the coronal features, is emphasized by the analysis of the dynamics of the main structures of the corona, which evolve at differential times. Studying coronal variability in its complexity is not easy because the times of evolution of the different structures can vary considerably: from seconds to several months. The typical sizes of the regions where coronal events take place vary in the same way, as it is shown in the following table.

| Coronal event | Typical time-scale | Typical length-scale (Mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Active region flare | 10 to 10000seconds | 10–100 |

| X-ray bright point | minutes | 1–10 |

| Transient in large-scale structures | from minutes to hours | ~100 |

| Transient in interconnecting arcs | from minutes to hours | ~100 |

| Quiet Sun | from hours to months | 100–1000 |

| Coronal hole | several rotations | 100–1000 |

Flares

Main article: Solar flares

Flares take place in active regions and are characterized by a sudden increase of the radiative flux emitted from small regions of the corona. They are very complex phenomena, visible at different wavelengths; they involve several zones of the solar atmosphere and many physical effects, thermal and not thermal, and sometimes wide reconnections of the magnetic field lines with material expulsion.

Flares are impulsive phenomena, of average duration of 15 minutes, and the most energetic events can last several hours. Flares produce a high and rapid increase of the density and temperature.

An emission in white light is only seldom observed: usually, flares are only seen at extreme UV wavelengths and into the X-rays, typical of the chromospheric and coronal emission.

In the corona, the morphology of flares is described by observations in the UV, soft and hard X-rays, and in Hα wavelengths, and is very complex. However, two kinds of basic structures can be distinguished:

- Compact flares, when each of the two arches where the event is happening maintains its morphology: only an increase of the emission is observed without significant structural variations. The emitted energy is of the order of 10 – 10 J.

- Flares of long duration, associated with eruptions of prominences, transients in white light and two-ribbon flares: in this case the magnetic loops change their configuration during the event. The energies emitted during these flares are of such great proportion they can reach 10 J.

As for temporal dynamics, three different phases are generally distinguished, whose duration are not comparable. The durations of those periods depend on the range of wavelengths used to observe the event:

- An initial impulsive phase, whose duration is on the order of minutes, strong emissions of energy are often observed even in the microwaves, EUV wavelengths and in the hard X-ray frequencies.

- A maximum phase

- A decay phase, which can last several hours.

Sometimes also a phase preceding the flare can be observed, usually called as "pre-flare" phase.

Coronal mass ejections

Main article: Coronal mass ejectionOften accompanying large solar flares and prominences are coronal mass ejections (CME). These are enormous emissions of coronal material and magnetic field that travel outward from the Sun at up to 3000 km/s, containing roughly 10 times the energy of the solar flare or prominence that accompanies them. Some larger CMEs can propel hundreds of millions of tons of material into interplanetary space at roughly 1.5 million kilometers an hour.

Stellar coronae

Coronal stars are ubiquitous among the stars in the cool half of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. These coronae can be detected using X-ray telescopes. Some stellar coronae, particularly in young stars, are much more luminous than the Sun's. For example, FK Comae Berenices is the prototype for the FK Com class of variable star. These are giants of spectral types G and K with an unusually rapid rotation and signs of extreme activity. Their X-ray coronae are among the most luminous (Lx ≥ 10 erg·s or 10W) and the hottest known with dominant temperatures up to 40 MK.

The astronomical observations planned with the Einstein Observatory by Giuseppe Vaiana and his group showed that F-, G-, K- and M-stars have chromospheres and often coronae much like the Sun. The O-B stars, which do not have surface convection zones, have a strong X-ray emission. However these stars do not have coronae, but the outer stellar envelopes emit this radiation during shocks due to thermal instabilities in rapidly moving gas blobs. Also A-stars do not have convection zones but they do not emit at the UV and X-ray wavelengths. Thus they appear to have neither chromospheres nor coronae.

Physics of the corona

The matter in the external part of the solar atmosphere is in the state of plasma, at very high temperature (a few million kelvin) and at very low density (of the order of 10 particles/m). According to the definition of plasma, it is a quasi-neutral ensemble of particles which exhibits a collective behaviour.

The composition is similar to that in the Sun's interior, mainly hydrogen, but with much greater ionization of its heavier elements than that found in the photosphere. Heavier metals, such as iron, are partially ionized and have lost most of the external electrons. The ionization state of a chemical element depends strictly on the temperature and is regulated by the Saha equation in the lowest atmosphere, but by collisional equilibrium in the optically thin corona. Historically, the presence of the spectral lines emitted from highly ionized states of iron allowed determination of the high temperature of the coronal plasma, revealing that the corona is much hotter than the internal layers of the chromosphere.

The corona behaves like a gas which is very hot but very light at the same time: the pressure in the corona is usually only 0.1 to 0.6 Pa in active regions, while on the Earth the atmospheric pressure is about 100 kPa, approximately a million times higher than on the solar surface. However it is not properly a gas, because it is made of charged particles, basically protons and electrons, moving at different velocities. Supposing that they have the same kinetic energy on average (for the equipartition theorem), electrons have a mass roughly 1800 times smaller than protons, therefore they acquire more velocity. Metal ions are always slower. This fact has relevant physical consequences either on radiative processes (that are very different from the photospheric radiative processes), or on thermal conduction. Furthermore, the presence of electric charges induces the generation of electric currents and high magnetic fields. Magnetohydrodynamic waves (MHD waves) can also propagate in this plasma, even though it is still not clear how they can be transmitted or generated in the corona.

Radiation

See also: Coronal radiative lossesCoronal plasma is optically thin and therefore transparent to the electromagnetic radiation that it emits and to that coming from lower layers. The plasma is very rarefied and the photon mean free path overcomes by far all the other length-scales, including the typical sizes of common coronal features.

Electromagnetic radiation from the corona has been identified coming from three main sources, located in the same volume of space:

- The K-corona (K for kontinuierlich, "continuous" in German) is created by sunlight Thomson scattering off free electrons; doppler broadening of the reflected photospheric absorption lines spreads them so greatly as to completely obscure them, giving the spectral appearance of a continuum with no absorption lines.

- The F-corona (F for Fraunhofer) is created by sunlight bouncing off dust particles, and is observable because its light contains the Fraunhofer absorption lines that are seen in raw sunlight; the F-corona extends to very high elongation angles from the Sun, where it is called the zodiacal light.

- The E-corona (E for emission) is due to spectral emission lines produced by ions that are present in the coronal plasma; it may be observed in broad or forbidden or hot spectral emission lines and is the main source of information about the corona's composition.

Thermal conduction

In the corona thermal conduction occurs from the external hotter atmosphere towards the inner cooler layers. Responsible for the diffusion process of the heat are the electrons, which are much lighter than ions and move faster, as explained above.

When there is a magnetic field the thermal conductivity of the plasma becomes higher in the direction which is parallel to the field lines rather than in the perpendicular direction. A charged particle moving in the direction perpendicular to the magnetic field line is subject to the Lorentz force which is normal to the plane individuated by the velocity and the magnetic field. This force bends the path of the particle. In general, since particles also have a velocity component along the magnetic field line, the Lorentz force constrains them to bend and move along spirals around the field lines at the cyclotron frequency.

If collisions between the particles are very frequent, they are scattered in every direction. This happens in the photosphere, where the plasma carries the magnetic field in its motion. In the corona, on the contrary, the mean free-path of the electrons is of the order of kilometres and even more, so each electron can do a helicoidal motion long before being scattered after a collision. Therefore, the heat transfer is enhanced along the magnetic field lines and inhibited in the perpendicular direction.

In the direction longitudinal to the magnetic field, the thermal conductivity of the corona is where is the Boltzmann constant, is the temperature in kelvin, is the electron mass, is the electric charge of the electron, is the Coulomb logarithm, and is the Debye length of the plasma with particle density . The Coulomb logarithm is roughly 20 in the corona, with a mean temperature of 1 MK and a density of 10 particles/m, and about 10 in the chromosphere, where the temperature is approximately 10kK and the particle density is of the order of 10 particles/m, and in practice it can be assumed constant.

Thence, if we indicate with the heat for a volume unit, expressed in J m, the Fourier equation of heat transfer, to be computed only along the direction of the field line, becomes

Numerical calculations have shown that the thermal conductivity of the corona is comparable to that of copper.

Coronal seismology

Main article: Coronal seismologyCoronal seismology is a method of studying the plasma of the solar corona with the use of magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) waves. MHD studies the dynamics of electrically conducting fluids – in this case, the fluid is the coronal plasma. Philosophically, coronal seismology is similar to the Earth's seismology, the Sun's helioseismology, and MHD spectroscopy of laboratory plasma devices. In all these approaches, waves of various kinds are used to probe a medium. The potential of coronal seismology in the estimation of the coronal magnetic field, density scale height, fine structure and heating has been demonstrated by different research groups.

Coronal heating problem

Unsolved problem in physics: Why is the Sun's corona so much hotter than the Sun's surface? (more unsolved problems in physics)The coronal heating problem in solar physics relates to the question of why the temperature of the Sun's corona is millions of kelvins greater than the thousands of kelvins of the surface. Several theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, but it is still challenging to determine which is correct. The problem first emerged after the identification of unknown spectral lines in the solar spectrum with highly ionized iron and calcium atoms. The comparison of the coronal and the photospheric temperatures of 6000K, leads to the question of how the 200-times-hotter coronal temperature can be maintained. The problem is primarily concerned with how the energy is transported up into the corona and then converted into heat within a few solar radii.

The high temperatures require energy to be carried from the solar interior to the corona by non-thermal processes, because the second law of thermodynamics prevents heat from flowing directly from the solar photosphere (surface), which is at about 5800K, to the much hotter corona at about 1 to 3 MK (parts of the corona can even reach 10MK).

Between the photosphere and the corona, the thin region through which the temperature increases is known as the transition region. It ranges from only tens to hundreds of kilometers thick. Energy cannot be transferred from the cooler photosphere to the corona by conventional heat transfer as this would violate the second law of thermodynamics. An analogy of this would be a light bulb raising the temperature of the air surrounding it to something greater than its glass surface. Hence, some other manner of energy transfer must be involved in the heating of the corona.

The amount of power required to heat the solar corona can easily be calculated as the difference between coronal radiative losses and heating by thermal conduction toward the chromosphere through the transition region. It is about 1 kilowatt for every square meter of surface area on the Sun's chromosphere, or 1/40000 of the amount of light energy that escapes the Sun.

Many coronal heating theories have been proposed, but two theories have remained as the most likely candidates: wave heating and magnetic reconnection (or nanoflares). Through most of the past 50 years, neither theory has been able to account for the extreme coronal temperatures.

In 2012, high resolution (<0.2″) soft X-ray imaging with the High Resolution Coronal Imager aboard a sounding rocket revealed tightly wound braids in the corona. It is hypothesized that the reconnection and unravelling of braids can act as primary sources of heating of the active solar corona to temperatures of up to 4 million kelvin. The main heat source in the quiescent corona (about 1.5 million kelvin) is assumed to originate from MHD waves.

NASA's Parker Solar Probe is intended to approach the Sun to a distance of approximately 9.5 solar radii to investigate coronal heating and the origin of the solar wind. It was successfully launched on August 12, 2018 and by late 2022 had completed the first 13 of more than 20 planned close approaches to the Sun.

| Heating models | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic | Magnetic | |

|

DC (reconnection) | AC (waves) |

|

| |

Wave heating theory

The wave heating theory, proposed in 1949 by Évry Schatzman, proposes that waves carry energy from the solar interior to the solar chromosphere and corona. The Sun is made of plasma rather than ordinary gas, so it supports several types of waves analogous to sound waves in air. The most important types of wave are magneto-acoustic waves and Alfvén waves. Magneto-acoustic waves are sound waves that have been modified by the presence of a magnetic field, and Alfvén waves are similar to ultra low frequency radio waves that have been modified by interaction with matter in the plasma. Both types of waves can be launched by the turbulence of granulation and super granulation at the solar photosphere, and both types of waves can carry energy for some distance through the solar atmosphere before turning into shock waves that dissipate their energy as heat.

One problem with wave heating is delivery of the heat to the appropriate place. Magneto-acoustic waves cannot carry sufficient energy upward through the chromosphere to the corona, both because of the low pressure present in the chromosphere and because they tend to be reflected back to the photosphere. Alfvén waves can carry enough energy, but do not dissipate that energy rapidly enough once they enter the corona. Waves in plasmas are notoriously difficult to understand and describe analytically, but computer simulations, carried out by Thomas Bogdan and colleagues in 2003, seem to show that Alfvén waves can transmute into other wave modes at the base of the corona, providing a pathway that can carry large amounts of energy from the photosphere through the chromosphere and transition region and finally into the corona where it dissipates it as heat.

Another problem with wave heating has been the complete absence, until the late 1990s, of any direct evidence of waves propagating through the solar corona. The first direct observation of waves propagating into and through the solar corona was made in 1997 with the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory space-borne solar observatory, the first platform capable of observing the Sun in the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) for long periods of time with stable photometry. Those were magneto-acoustic waves with a frequency of about 1 millihertz (mHz, corresponding to a 1000second wave period), that carry only about 10% of the energy required to heat the corona. Many observations exist of localized wave phenomena, such as Alfvén waves launched by solar flares, but those events are transient and cannot explain the uniform coronal heat.

It is not yet known exactly how much wave energy is available to heat the corona. Results published in 2004 using data from the TRACE spacecraft seem to indicate that there are waves in the solar atmosphere at frequencies as high as 100mHz (10 second period). Measurements of the temperature of different ions in the solar wind with the UVCS instrument aboard SOHO give strong indirect evidence that there are waves at frequencies as high as 200Hz, well into the range of human hearing. These waves are very difficult to detect under normal circumstances, but evidence collected during solar eclipses by teams from Williams College suggest the presences of such waves in the 1–10Hz range.

Recently, Alfvénic motions have been found in the lower solar atmosphere and also in the quiet Sun, in coronal holes and in active regions using observations with AIA on board the Solar Dynamics Observatory. These Alfvénic oscillations have significant power, and seem to be connected to the chromospheric Alfvénic oscillations previously reported with the Hinode spacecraft.

Solar wind observations with the Wind spacecraft have recently shown evidence to support theories of Alfvén-cyclotron dissipation, leading to local ion heating.

Magnetic reconnection theory

Main article: Magnetic reconnection

The magnetic reconnection theory relies on the solar magnetic field to induce electric currents in the solar corona. The currents then collapse suddenly, releasing energy as heat and wave energy in the corona. This process is called "reconnection" because of the peculiar way that magnetic fields behave in plasma (or any electrically conductive fluid such as mercury or seawater). In a plasma, magnetic field lines are normally tied to individual pieces of matter, so that the topology of the magnetic field remains the same: if a particular north and south magnetic pole are connected by a single field line, then even if the plasma is stirred or if the magnets are moved around, that field line will continue to connect those particular poles. The connection is maintained by electric currents that are induced in the plasma. Under certain conditions, the electric currents can collapse, allowing the magnetic field to "reconnect" to other magnetic poles and release heat and wave energy in the process.

Magnetic reconnection is hypothesized to be the mechanism behind solar flares, the largest explosions in the Solar System. Furthermore, the surface of the Sun is covered with millions of small magnetized regions 50–1000km across. These small magnetic poles are buffeted and churned by the constant granulation. The magnetic field in the solar corona must undergo nearly constant reconnection to match the motion of this "magnetic carpet", so the energy released by the reconnection is a natural candidate for the coronal heat, perhaps as a series of "microflares" that individually provide very little energy but together account for the required energy.

The idea that nanoflares might heat the corona was proposed by Eugene Parker in the 1980s but is still controversial. In particular, ultraviolet telescopes such as TRACE and SOHO/EIT can observe individual micro-flares as small brightenings in extreme ultraviolet light, but there seem to be too few of these small events to account for the energy released into the corona. The additional energy not accounted for could be made up by wave energy, or by gradual magnetic reconnection that releases energy more smoothly than micro-flares and therefore does not appear well in the TRACE data. Variations on the micro-flare hypothesis use other mechanisms to stress the magnetic field or to release the energy, and are a subject of active research in 2005.

Spicules (type II)

For decades, researchers believed spicules could send heat into the corona. However, following observational research in the 1980s, it was found that spicule plasma did not reach coronal temperatures, and so the theory was discounted.

As per studies performed in 2010 at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, in collaboration with the Lockheed Martin's Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory (LMSAL) and the Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics of the University of Oslo, a new class of spicules (TYPE II) discovered in 2007, which travel faster (up to 100 km/s) and have shorter lifespans, can account for the problem. These jets insert heated plasma into the Sun's outer atmosphere.

Thus, a much greater understanding of the corona and improvement in the knowledge of the Sun's subtle influence on the Earth's upper atmosphere can be expected henceforth. The Atmospheric Imaging Assembly on NASA's recently launched Solar Dynamics Observatory and NASA's Focal Plane Package for the Solar Optical Telescope on the Japanese Hinode satellite which was used to test this hypothesis. The high spatial and temporal resolutions of the newer instruments reveal this coronal mass supply.

These observations reveal a one-to-one connection between plasma that is heated to millions of degrees and the spicules that insert this plasma into the corona.

See also

References

- Liberatore, Alessandro; Capobianco, Gerardo; Fineschi, Silvano; Massone, Giuseppe; Zangrilli, Luca; Susino, Roberto; Nicolini, Gianalfredo (March 2022). "Sky Brightness Evaluation at Concordia Station, Dome C, Antarctica, for Ground-Based Observations of the Solar Corona". Solar Physics. 297 (3): 29. arXiv:2201.00660. Bibcode:2022SoPh..297...29L. doi:10.1007/s11207-022-01958-x. PMC 8889400. PMID 35250102.

- ^ Aschwanden, Markus J. (2005). Physics of the Solar Corona: An Introduction with Problems and Solutions. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing. ISBN 978-3-540-22321-4.

- Hall, Graham; et al. (2007). "Maraldi, Giacomo Filippo". Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. p. 736. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_899. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- de Ferrer, José Joaquín (1809). "Observations of the eclipse of the sun June 16th 1806 made at Kinderhook in the State of New York". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 6: 264–275. doi:10.2307/1004801. JSTOR 1004801.

- Espenak, Fred. "Chronology of Discoveries about the Sun". Mr. Eclipse. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Golub & Pasachoff (1997). "The Solar Corona", Cambridge University Press (London), ISBN 0 521 48082 5, p. 4

- Vaiana, G. S.; Krieger, A. S.; Timothy, A. F. (1973). "Identification and analysis of structures in the corona from X-ray photography". Solar Physics. 32 (1): 81–116. Bibcode:1973SoPh...32...81V. doi:10.1007/BF00152731. S2CID 121940724.

- Vaiana, G.S.; Tucker, W.H. (1974). "Solar X-Ray Emission". In R. Giacconi; H. Gunsky (eds.). X-Ray Astronomy. p. 169.

- Vaiana, G S; Rosner, R (1978). "Recent advances in Coronae Physics". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 16: 393–428. Bibcode:1978ARA&A..16..393V. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.16.090178.002141.

- ^ Gibson, E. G. (1973). The Quiet Sun. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C.

- "How NASA Revealed Sun's Hottest Secret in 5-Minute Spaceflight". Space.com. 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-01-24.

- Katsukawa, Yukio; Tsuneta, Saku (2005). "Magnetic Properties at Footpoints of Hot and Cool Loops". The Astrophysical Journal. 621 (1): 498–511. Bibcode:2005ApJ...621..498K. doi:10.1086/427488.

- Betta, Rita; Orlando, Salvatore; Peres, Giovanni; Serio, Salvatore (1999). "On the Stability of Siphon Flows in Coronal Loops". Space Science Reviews. 87: 133–136. Bibcode:1999SSRv...87..133B. doi:10.1023/A:1005182503751. S2CID 117127214.

- ^ Giacconi, Riccardo (1992). "G. S. Vaiana memorial lecture". In Linsky, J. F.; Serio, S. (eds.). Physics of Solar and Stellar Coronae: G.S. Vaiana Memorial Symposium: G.S. Vaiana Memorial Symposium : Proceedings of a Conference of the International Astronomical Union. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. pp. 3–19. ISBN 978-0-7923-2346-4.

- ^ Ofman, Leon (2000). "Source regions of the slow solar wind in coronal streamers". Geophysical Research Letters. 27 (18): 2885–2888. Bibcode:2000GeoRL..27.2885O. doi:10.1029/2000GL000097.

- Kariyappa, R.; Deluca, E. E.; Saar, S. H.; Golub, L.; Damé, L.; Pevtsov, A. A.; Varghese, B. A. (2011). "Temperature variability in X-ray bright points observed with Hinode/XRT". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 526: A78. Bibcode:2011A&A...526A..78K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014878.

- Ito, Hiroaki; Tsuneta, Saku; Shiota, Daikou; Tokumaru, Munetoshi; Fujiki, Ken'Ichi (2010). "Is the Polar Region Different from the Quiet Region of the Sun?". The Astrophysical Journal. 719 (1): 131–142. arXiv:1005.3667. Bibcode:2010ApJ...719..131I. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/719/1/131. S2CID 118504417.

- Del Zanna, G.; Bromage, B. J. I.; Mason, H. E. (2003). "Spectroscopic characteristics of polar plumes". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 398 (2): 743–761. Bibcode:2003A&A...398..743D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021628.

- Adhikari, L.; Zank, G. P.; Zhao, L.-L. (30 April 2019). "Does Turbulence Turn off at the Alfvén Critical Surface?". The Astrophysical Journal. 876 (1): 26. Bibcode:2019ApJ...876...26A. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab141c. S2CID 156048833.

- DeForest, C. E.; Howard, T. A.; McComas, D. J. (12 May 2014). "Inbound waves in the solar corona: a direct indicator of Alfvén Surface location". The Astrophysical Journal. 787 (2): 124. arXiv:1404.3235. Bibcode:2014ApJ...787..124D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/787/2/124. S2CID 118371646.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hatfield, Miles (13 December 2021). "NASA Enters the Solar Atmosphere for the First Time". NASA.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hatfield, Miles (13 December 2021). "NASA Enters the Solar Atmosphere for the First Time". NASA.

- Pallavicini, R.; Serio, S.; Vaiana, G. S. (1977). "A survey of soft X-ray limb flare images – The relation between their structure in the corona and other physical parameters". The Astrophysical Journal. 216: 108. Bibcode:1977ApJ...216..108P. doi:10.1086/155452.

- Golub, L.; Herant, M.; Kalata, K.; Lovas, I.; Nystrom, G.; Pardo, F.; Spiller, E.; Wilczynski, J. (1990). "Sub-arcsecond observations of the solar X-ray corona". Nature. 344 (6269): 842–844. Bibcode:1990Natur.344..842G. doi:10.1038/344842a0. S2CID 4346856.

- "Coronal Mass Ejections". NOAA / NWS Space Weather Prediction Center. April 3, 2024. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ Güdel M (2004). "X-ray astronomy of stellar coronae" (PDF). The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 12 (2–3): 71–237. arXiv:astro-ph/0406661. Bibcode:2004A&ARv..12...71G. doi:10.1007/s00159-004-0023-2. S2CID 119509015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11.

- Vaiana, G.S.; et al. (1981). "Results from an extensive Einstein stellar survey". The Astrophysical Journal. 245: 163. Bibcode:1981ApJ...245..163V. doi:10.1086/158797.

- Jeffrey, Alan (1969). Magneto-hydrodynamics. UNIVERSITY MATHEMATICAL TEXTS.

- Corfield, Richard (2007). Lives of the Planets. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01403-3.

- ^ Spitzer, L. (1962). Physics of fully ionized gas. Interscience tracts of physics and astronomy.

- ^ "2004ESASP.575....2K Page 2". adsbit.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ Aschwanden, Markus (2006). Physics of the Solar Corona: An Introduction with Problems and Solutions. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 355. doi:10.1007/3-540-30766-4_9. ISBN 978-3-540-30765-5.

- Falgarone, Edith; Passot, Thierry (2003). Turbulence and Magnetic Fields in Astrophysics. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 28. ISBN 978-3-540-00274-1.

- Ulmshneider, Peter (1997). J.C. Vial; K. Bocchialini; P. Boumier (eds.). Heating of Chromospheres and Coronae in Space Solar Physics, Proceedings, Orsay, France. Springer. pp. 77–106. ISBN 978-3-540-64307-4.

- Malara, F.; Velli, M. (2001). Pål Brekke; Bernhard Fleck; Joseph B. Gurman (eds.). Observations and Models of Coronal Heating in Recent Insights into the Physics of the Sun and Heliosphere: Highlights from SOHO and Other Space Missions, Proceedings of IAU Symposium 203. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 456–466. ISBN 978-1-58381-069-9.

- Cirtain, J. W.; Golub, L.; Winebarger, A. R.; De Pontieu, B.; Kobayashi, K.; Moore, R. L.; Walsh, R. W.; Korreck, K. E.; Weber, M.; McCauley, P.; Title, A.; Kuzin, S.; Deforest, C. E. (2013). "Energy release in the solar corona from spatially resolved magnetic braids". Nature. 493 (7433): 501–503. Bibcode:2013Natur.493..501C. doi:10.1038/nature11772. PMID 23344359. S2CID 205232074.

- "Parker Solar Probe: The Mission". parkersolarprobe.jhuapl.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-08-22.

- "Parker Solar Probe Completes Third Close Approach of the Sun". blogs.nasa.gov. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- Alfvén, Hannes (1947). "Magneto hydrodynamic waves, and the heating of the solar corona". MNRAS. 107 (2): 211–219. Bibcode:1947MNRAS.107..211A. doi:10.1093/mnras/107.2.211.

- "Alfven Waves – Our Sun Is Doing The Magnetic Twist". read on Jan 6 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23.

- Jess, D. B.; Mathioudakis, M.; Erdélyi, R.; Crockett, P. J.; Keenan, F. P.; Christian, D. J. (2009). "Alfvén Waves in the Lower Solar Atmosphere". Science. 323 (5921): 1582–1585. arXiv:0903.3546. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1582J. doi:10.1126/science.1168680. hdl:10211.3/172550. PMID 19299614. S2CID 14522616.

- McIntosh, S. W.; de Pontieu, B.; Carlsson, M.; Hansteen, V. H.; The Sdo; Aia Mission Team (Fall 2010). "Ubiquitous Alfvenic Motions in Quiet Sun, Coronal Hole and Active Region Corona". American Geophysical Union. abstract #SH14A-01: SH14A–01. Bibcode:2010AGUFMSH14A..01M.

- "Sun's Magnetic Secret Revealed". Space.com. 22 January 2008. Archived from the original on 2010-12-24. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- Kasper, J.C.; et al. (December 2008). "Hot Solar-Wind Helium: Direct Evidence for Local Heating by Alfven-Cyclotron Dissipation". Physical Review Letters. 101 (26): 261103. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101z1103K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.261103. PMID 19113766.

- Priest, Eric (1982). Solar Magneto-hydrodynamics. Dordrecht, Holland: D.Reidel. ISBN 978-90-277-1833-4.

- Patsourakos, S.; Vial, J.-C. (2002). "Intermittent behavior in the transition region and the low corona of the quiet Sun". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 385 (3): 1073–1077. Bibcode:2002A&A...385.1073P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020151.

- "Mystery of Sun's hot outer atmosphere 'solved'". Rediff. 2011-01-07. Archived from the original on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- De Pontieu, B.; McIntosh, S. W.; Carlsson, M.; Hansteen, V. H.; Tarbell, T.D.; Boerner, P.; Martinez-Sykora, J.; Schrijver, C. J.; Title, A. M. (2011). "The Origins of Hot Plasma in the Solar Corona". Science. 331 (6013): 55–58. Bibcode:2011Sci...331...55D. doi:10.1126/science.1197738. PMID 21212351. S2CID 42068767.

External links

- NASA description of the solar corona Archived 2010-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Coronal heating problem at Innovation Reports

- NASA/GSFC description of the coronal heating problem

- FAQ about coronal heating

- Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, including near-real-time images of the solar corona

- Coronal x-ray images from the Hinode XRT

- nasa.gov Astronomy Picture of the Day July 26, 2009 – a combination of thirty-three photographs of the Sun's corona that were digitally processed to highlight faint features of a total eclipse that occurred in March 2006

- Animated explanation of the core of the Sun Archived 2015-11-16 at the Wayback Machine (University of South Wales)

- Alfvén waves may heat the Sun's corona

- Solar Interface Region – Bart de Pontieu (SETI Talks) Video

| Stars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation | |||||||

| Evolution | |||||||

| Classification |

| ||||||

| Nucleosynthesis | |||||||

| Structure | |||||||

| Properties | |||||||

| Star systems | |||||||

| Earth-centric observations | |||||||

| Lists | |||||||

| Related | |||||||

| Solar eclipses | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Features | |||||||||

| Lists of eclipses |

| ||||||||

Total/hybrid eclipses → next total/hybrid |

| ||||||||

Annular eclipses → next annular |

| ||||||||

Partial eclipses → next partial |

| ||||||||

| Other bodies | |||||||||

| Related | |||||||||

can be calculated by the

can be calculated by the  , where

, where  is the

is the  the

the  the plasma temperature. It is evident from the equation that the plasma pressure lowers when the plasma temperature decreases with respect to the surrounding regions or when the zone of intense magnetic field empties. The same physical effect renders sunspots apparently dark in the photosphere.

the plasma temperature. It is evident from the equation that the plasma pressure lowers when the plasma temperature decreases with respect to the surrounding regions or when the zone of intense magnetic field empties. The same physical effect renders sunspots apparently dark in the photosphere.

where

where  is the

is the  is the electron mass,

is the electron mass,  is the electric charge of the electron,

is the electric charge of the electron,

is the Coulomb logarithm, and

is the Coulomb logarithm, and

is the

is the  is roughly 20 in the corona, with a mean temperature of 1 MK and a density of 10 particles/m, and about 10 in the chromosphere, where the temperature is approximately 10kK and the particle density is of the order of 10 particles/m, and in practice it can be assumed constant.

is roughly 20 in the corona, with a mean temperature of 1 MK and a density of 10 particles/m, and about 10 in the chromosphere, where the temperature is approximately 10kK and the particle density is of the order of 10 particles/m, and in practice it can be assumed constant.

the heat for a volume unit, expressed in J m, the Fourier equation of heat transfer, to be computed only along the direction

the heat for a volume unit, expressed in J m, the Fourier equation of heat transfer, to be computed only along the direction  of the field line, becomes

of the field line, becomes