Medical condition

| Volvulus | |

|---|---|

| |

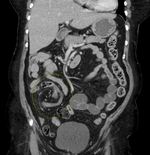

| Coronal CT of the abdomen, demonstrating a volvulus as indicated by twisting of the bowel stock | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, vomiting, constipation, bloody stool |

| Complications | Ischemic bowel |

| Usual onset | Rapid or more gradual |

| Risk factors | Intestinal malrotation, enlarged colon, Hirschsprung disease, pregnancy, abdominal adhesions, chronic constipation |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging (plain X-rays, GI series, CT scan) |

| Treatment | Sigmoidoscopy, barium enema, bowel resection |

| Frequency | 2.5 per 100,000 per year |

A volvulus is when a loop of intestine twists around itself and the mesentery that supports it, resulting in a bowel obstruction. Symptoms include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, vomiting, constipation, and bloody stool. Onset of symptoms may be rapid or more gradual. The mesentery may become so tightly twisted that blood flow to part of the intestine is cut off, resulting in ischemic bowel. In this situation there may be fever or significant pain when the abdomen is touched.

Risk factors include a birth defect known as intestinal malrotation, an enlarged colon, Hirschsprung disease, pregnancy, and abdominal adhesions. Long term constipation and a high fiber diet may also increase the risk. The most commonly affected part of the intestines in adults is the sigmoid colon with the cecum being second most affected. In children the small intestine is more often involved. The stomach can also be affected. Diagnosis is typically with medical imaging such as plain X-rays, a GI series, or CT scan.

Initial treatment for sigmoid volvulus may occasionally occur via sigmoidoscopy or with a barium enema. Due to the high risk of recurrence, a bowel resection within the next two days is generally recommended. If the bowel is severely twisted or the blood supply is cut off, immediate surgery is required. In a cecal volvulus, often part of the bowel needs to be surgically removed. If the cecum is still healthy, it may occasionally be returned to a normal position and sutured in place.

Cases of volvulus were described in ancient Egypt as early as 1550 BC. It occurs most frequently in Africa, the Middle East, and India. Rates of volvulus in the United States are about 2–3 per 100,000 people per year. Sigmoid and cecal volvulus typically occurs between the ages of 30 and 70. Outcomes are related to whether or not the bowel tissue has died. The term volvulus is from the Latin "volvere"; which means "to roll".

Signs and symptoms

Regardless of cause, volvulus causes symptoms by two mechanisms:

- Bowel obstruction manifested as abdominal distension and bilious vomiting.

- Ischemia (loss of blood flow) to the affected portion of intestine.

Depending on the location of the volvulus, symptoms may vary. For example, in patients with cecal volvulus, the predominant symptoms may be those of small bowel obstruction (nausea, vomiting and lack of stool or flatus), because the obstructing point is close to the ileocecal valve and small intestine. In patients with sigmoid volvulus, although abdominal pain may be present, symptoms of constipation may be more prominent.

Volvulus causes severe pain and progressive injury to the intestinal wall, with accumulation of gas and fluid in the portion of the bowel obstructed. Ultimately, this can result in necrosis of the affected intestinal wall, acidosis, and death. This is known as a closed-loop obstruction because there exists an isolated ("closed") loop of bowel. Acute volvulus often requires immediate surgical intervention to untwist the affected segment of bowel and possibly resect any unsalvageable portion.

Volvulus occurs most frequently in middle-aged and elderly men. Volvulus can also arise as a rare complication in persons with redundant colon, a normal anatomic variation resulting in extra colonic loops.

Sigmoid volvulus is the most-common form of volvulus of the gastrointestinal tract. and is responsible for 8% of all intestinal obstructions. Sigmoid volvulus is particularly common in elderly persons and constipated patients. Patients experience abdominal pain, distension, and absolute constipation.

Cecal volvulus is slightly less common than sigmoid volvulus and is associated with symptoms of abdominal pain and small bowel obstruction.

Volvulus can also occur in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy due to smooth muscle dysfunction.

Gastric volvulus causes nausea, vomiting, and pain in the upper abdomen. The Borchardt triad is a group of symptoms that help doctors to identify gastric volvulus. The symptoms are intractable retching, pain in the upper abdomen and inability to pass nasogastric tube into the stomach.

Complications

- Strangulation

- Gangrene

- Perforation

- Faecal peritonitis

- Recurrent volvulus

Causes

Midgut volvulus occurs in people (usually babies) that are predisposed because of congenital intestinal malrotation. Segmental volvulus occurs in people of any age, usually with a predisposition because of abnormal intestinal contents (e.g. meconium ileus) or adhesions. Volvulus of the cecum, transverse colon, or sigmoid colon occurs, usually in adults, with only minor predisposing factors such as redundant (excess, inadequately supported) intestinal tissue and constipation.

Types

- volvulus neonatorum

- volvulus of the small intestine

- midgut volvulus (due to intestinal malrotation)

- volvulus of the caecum (cecum), also cecal volvulus

- sigmoid colon volvulus (sigmoid volvulus)

- volvulus of the transverse colon

- volvulus of the splenic flexure, the rarest

- gastric volvulus

- ileosigmoid knot

Diagnosis

After taking a thorough history, the diagnosis of colonic volvulus is usually easily included in the differential diagnosis. Abdominal plain x-rays are commonly confirmatory for a volvulus, especially if a coffee bean sign is seen. These refer to the shape of the air-filled closed loop of colon which forms the volvulus. Should the diagnosis be in doubt, a barium enema may be used to demonstrate a "bird's beak" at the point where the segment of proximal bowel and distal bowel rotate to form the volvulus.

This area shows an acute and sharp tapering and looks like a bird's beak. If a perforation is suspected, barium should not be used due to its potentially lethal effects when distributed throughout the free intraperitoneal cavity. Gastrografin, which is safer, can be substituted for barium.

The differential diagnosis includes the much more common constricting or obstructing carcinoma. In approximately 80 percent of colonic obstructions, invasive carcinoma is found to be the cause of the obstruction. This is usually easily diagnosed with endoscopic biopsies.

Diverticulitis is a common condition with different presentations. Although diverticulitis may be the source of a colonic obstruction, it more commonly causes an ileus, which appears to be a colonic obstruction. Endoscopic means can be used to secure a diagnosis although this may cause a perforation of the inflamed diverticular area. CT scanning is the more common method to diagnose diverticulitis. The scan will show mesenteric stranding in the involved segment of edematous colon which is usually in the sigmoid region. Micro perforations with free air may be seen.

Ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease may cause colonic obstruction. The obstruction may be acute or chronic after years of uncontrolled disease leads to the formation of strictures and fistulas. The medical history is helpful in that most cases of inflammatory bowel disease are well known to both patient and doctor.

Other rare syndromes, including Ogilvie's syndrome, chronic constipation and impaction may cause a pseudo obstruction.

- Abdominal x-ray – tire-like shadow arising from right iliac fossa and passing to left

- Upper GI series

-

Coffee bean sign in a person with sigmoid volvulus

Coffee bean sign in a person with sigmoid volvulus

-

Coronal view of sigmoid volvulus with "whirlpool sign"

Coronal view of sigmoid volvulus with "whirlpool sign"

-

CT scan of a small bowel volvulus. It shows two juxtaposed segments of narrowing, which is the spot of mesentery rotation. The other signs indicate strangulation.

CT scan of a small bowel volvulus. It shows two juxtaposed segments of narrowing, which is the spot of mesentery rotation. The other signs indicate strangulation.

-

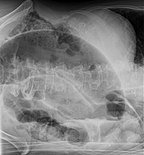

An x-ray of a person with a small bowel volvulus.

-

Plain X ray of a cecal volvulus

Plain X ray of a cecal volvulus

-

CT scan of a cecal volvulus

CT scan of a cecal volvulus

Treatment

Sigmoid

Treatment for sigmoid volvulus may include sigmoidoscopy. If the mucosa of the sigmoid looks normal and pink, a rectal tube for decompression may be placed, and any fluid, electrolyte, cardiac, kidney or pulmonary abnormalities should be corrected. The affected person should then be taken to the operating room for surgical repair. If surgery is not performed, there is a high rate of recurrence.

For people with signs of sepsis or an abdominal catastrophe, immediate surgery and resection are advised.

Cecal

In a cecal volvulus, the cecum may be returned to a normal position and sutured in place, a procedure known as cecopexy. If identified early, before presumed intestinal wall ischemia has resulted in tissue breakdown and necrosis, the cecal volvulus can be detorsed laparoscopically. It has been associated to several diseases, including Huntington's disease.

Other

Laparotomy for other forms of volvulus, especially anal volvulus.

References

- ^ "Anatomic Problems of the Lower GI Tract". NIDDK. July 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R (2013). "95". Rosen's Emergency Medicine - Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-4987-4. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16.

- ^ Gingold D, Murrell Z (December 2012). "Management of colonic volvulus". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 25 (4): 236–44. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1329535. PMC 3577612. PMID 24294126.

The Papyrus Ebers, ca. 1550 BC, described the natural course of volvulus to be spontaneous reduction or "rotting" of the intestines

- ^ Gordon PH, Nivatvongs S (2007). Principles and Practice of Surgery for the Colon, Rectum, and Anus, Third Edition. CRC Press. p. 971. ISBN 978-1-4200-1799-1. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17.

- Wilkins LW (2009). Professional Guide to Diseases. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-7817-7899-2.

- Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ (2010). Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management, Expert Consult Premium Edition - Enhanced Online Features (9 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-4377-2767-8. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16.

- Brothwell DR, R DW, Sandison AT (14 May 2014). Diseases in Antiquity: A Survey of the Diseases, Injuries, and Surgery of Early Populations. Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Limited. ISBN 978-0-398-08909-2.

- Ballantyne GH (July 1982). "Review of sigmoid volvulus: History and results of treatment". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 25 (5): 494–501. doi:10.1007/BF02553666. PMID 7047106. S2CID 37405850.

- Beck D, Beck DE (2012). "23". Handbook of Colorectal Surgery: Third Edition. JP Medical Ltd. ISBN 978-1-907816-20-8. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16.

- ^ "Volvulus". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Wedding, Mary Ellen, Gylys, Barbara A. (2004). Medical Terminology Systems: A Body Systems Approach (Medical Terminology (W/CD & CD-ROM) (Davis)). Philadelphia, Pa: F. A. Davis Company. ISBN 0-8036-1249-4.

- Mayo Clinic Staff (2006-10-13). "Redundant colon: A health concern?". Ask a Digestive System Specialist. MayoClinic.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- Turan M, Sen M, Karadayi K, et al. (January 2004). "Our sigmoid colon volvulus experience and benefits of colonoscope in detortion process". Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 96 (1): 32–5. doi:10.4321/s1130-01082004000100005. PMID 14971995. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11.

- Peterson CM, Anderson JS, Hara AK, Carenza JW, Menias CO (September 2009). "Volvulus of the Gastrointestinal Tract: Appearances at Multimodality Imaging". RadioGraphics. 29 (5): 1281–1293. doi:10.1148/rg.295095011. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 19755596.

- Le CK, Nahirniak P, Anand S, Cooper W (2023). "Volvulus". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 28722866. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Hoffman, Gary H. (2007-08-16). "Diverticulosis/Diverticulitis - For Physicians". Time To Call The Surgeon?. Los Angeles Colon and Rectal Surgical Associates. LAcolon.com. Archived from the original on 2013-02-26. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- Hoffman, Gary H. (2009-10-27). "What is Constipation?". What Can Be Done About Constipation. Los Angeles Colon and Rectal Surgical Associates. LAcolon.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-13. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- Jones RG, Wayne EJ, Kehdy FJ (May 2012). "Laparoscopic detorsion and cecopexy for treatment of cecal volvulus". The American Surgeon. 78 (5): E251–252. doi:10.1177/000313481207800503. ISSN 1555-9823. PMID 22546094. S2CID 5812146.

- Ferrer-Inaebnit E, Segura-Sampedro JJ, Molina-Romero FX, González-Argenté X (October 2020). "Oclusión e isquemia por vólvulo de ciego en corea de Huntington". Gastroenterología y Hepatología (in Spanish). 43 (10): 633–634. doi:10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.03.005. PMID 33051047. S2CID 241550167.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Diseases of the human digestive system | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper GI tract |

| ||||||||||

| Lower GI tract Enteropathy |

| ||||||||||

| GI bleeding | |||||||||||

| Accessory |

| ||||||||||

| Other |

| ||||||||||