| Revision as of 18:52, 4 February 2008 editTimVickers (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users58,184 edits →Ethics: not in source← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:00, 2 January 2025 edit undo2601AC47 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers1,145 edits Reverted 1 pending edit by Neraked to revision 1261076662 by TehCoolMan: Broke something.Tag: Manual revert | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Use of animals in experiments}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc}} | |||

| <!--NOTE TO EDITORS: THIS IS A CONTROVERSIAL TOPIC. PLEASE DO NOT DELETE MATERIAL WITHOUT SECURING CONSENSUS ON THE TALK PAGE. IF YOU DO DELETE TEXT, BE PREPARED TO HAVE YOUR EDIT, INCLUDING ANY MATERIAL YOU HAVE ADDED, REVERTED.--> | |||

| {{Redirect|Animal research|other uses|Animal studies (disambiguation)|the journal|Animal Research (journal)}} | |||

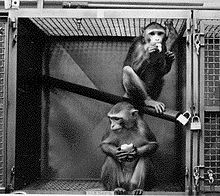

| ] before insertion into the ] capsule in 1961. Non-human ]s make up 0.3 percent of research animals, with 55,000 used each year in the U.S.<ref>, p. 10.</ref> and 10,000 in the European Union.<ref name=buavprimates> , British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.</ref><ref name=jha>Jha, Alok. , ''The Guardian'', December 9, 2005.</ref>]] | |||

| {{See also|Vivisection}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Pp-pc}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox| bodystyle = width:10em; font-size:85%; | |||

| |aboabovestyle = background-color: #99BADD | |||

| |subheader = | |||

| |image1 = ] | |||

| |caption1 = A ] | |||

| |headerstyle = background-color: #99BADD | |||

| |label2 = Description | |||

| |data2 = Around 50–100 million ] animals are used in experiments annually. | |||

| |label3 = Early proponents | |||

| |label4 = Modern proponents | |||

| |label5 = Key texts | |||

| |label6 = Subjects | |||

| |data6 = Animal testing, science, medicine, animal welfare, animal rights, ethics | |||

| |below = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Animal testing''', also known as '''animal experimentation''', '''animal research''', and '''''in vivo'' testing''', is the use of ], such as ]s, in experiments that seek to control the variables that affect the ] or ] under study. This approach can be contrasted with field studies in which animals are observed in their natural environments or habitats. Experimental research with animals is usually conducted in universities, medical schools, pharmaceutical companies, defense establishments, and commercial facilities that provide animal-testing services to the industry.<ref name=selectcommintro>{{cite web|url=https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200102/ldselect/ldanimal/150/15004.htm#a7 |title="Introduction", Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures Report|publisher=UK Parliament|access-date=2012-07-13}}</ref> The focus of animal testing varies on a continuum from ], focusing on developing fundamental knowledge of an organism, to applied research, which may focus on answering some questions of great practical importance, such as finding a cure for a disease.<ref name="Ethical">{{cite journal |author1=Liguori, G.| display-authors=etal| year = 2017 | title = Ethical Issues in the Use of Animal Models for Tissue Engineering: Reflections on Legal Aspects, Moral Theory, 3Rs Strategies, and Harm-Benefit Analysis| journal = Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods | volume = 23 | issue = 12 | pages= 850–62 | doi=10.1089/ten.TEC.2017.0189| pmid=28756735| s2cid=206268293| url=https://pure.rug.nl/ws/files/51950145/ten.tec.2017.0189.pdf}}</ref> Examples of applied research include testing disease treatments, breeding, defense research, and ], including ]. In education, animal testing is sometimes a component of ] or ] courses.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Hajar |first=Rachel |date=2011 |title=Animal Testing and Medicine |journal=Heart Views |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=42 |doi=10.4103/1995-705X.81548 |issn=1995-705X |pmc=3123518 |pmid=21731811 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| '''Animal testing''' or '''animal research''' refers to the use of non-human animals in experiments. It is estimated that 50 to 100 million ] animals worldwide — from ] to ] — are used annually and killed during or after the experiments.<ref>, British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection; , Research Defence Society; , Nuffield Council on Bioethics, section 1.6. </ref> Although much larger numbers of ]s are used and the use of flies and worms as ]s is very important, experiments on invertebrates are largely unregulated and not included in statistics. Sources of laboratory animals vary between countries and species; while most animals are purpose-bred, others may be caught in the wild or supplied by dealers who obtain them from auctions and ].<ref>"Use of Laboratory Animals in Biomedical and Behavioral Research", Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, The National Academies Press, 1988. Also see Cooper, Sylvia. "Pets crowd animal shelter", ''The Augusta Chronicle'', August 1, 1999; and Gillham, Christina. , ''Newsweek'', February 17, 2006.</ref> | |||

| Research using animal models has been central to most of the achievements of modern medicine.<ref name=RSM2015/><ref name=NRCIOM/><ref name="Nature2007"/> It has contributed to most of the basic knowledge in fields such as human ] and ], and has played significant roles in fields such as ] and ].<ref name=NRCIOMb/><ref name="HLAS2011"/> The results have included the near-] and the development of ], and have benefited both humans and animals.<ref name=RSM2015/><ref name="IOM1991"/> From 1910 to 1927, ]'s work with the fruit fly '']'' identified ]s as the vector of inheritance for genes,<ref name="nobelprize.org"/><ref name="nobel2"/> and ] wrote that Morgan's discoveries "helped transform biology into an experimental science".<ref name="Kandel1999"/> Research in model organisms led to further medical advances, such as the production of the ]<ref name="nobel3"/><ref name="Cannon2009"/> and the 1922 discovery of ]<ref name="insulin"/> and its use in treating diabetes, which had previously meant death.<ref name="Thompson2009"/> Modern general anaesthetics such as ] were also developed through studies on model organisms, and are necessary for modern, complex surgical operations.<ref name="raventos1956"/> Other 20th-century medical advances and treatments that relied on research performed in animals include ] techniques,<ref name="carrel1912"/><ref name="williamson1926">Williamson C (1926) ''J. Urol.'' 16: p. 231</ref><ref name="woodruff1986"/><ref name="moore1964"/> the heart-lung machine,<ref name="gibbon1937"/> ]s,<ref name="rawbw"/><ref name="fleming1929"/> and the ] vaccine.<ref name="mrc1956"/> | |||

| The research is carried out inside universities, medical schools, pharmaceutical companies, farms, defense-research establishments, and commercial facilities that provide animal-testing services to industry.<ref name=selectcommintro>, Select Committee on Animals In Scientific Procedures Report, United Kingdom Parliament.</ref> The types of research carried out include pure research such as ]s, ], and ], as well as applied research such as ] and toxicology or drug testing. Animals are also used for education, breeding, and defense research. | |||

| Animal testing is widely used to aid in research of human ] when ] would be unfeasible or ].<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yTfNH3cScKAC<!--confirmed ISBN match; full text access-->|title=The Case for Animal Experimention: An Evolutionary and Ethical Perspective|last=Fox|first=Michael Allen|publisher=University of California Press|year=1986|isbn=978-0-520-05501-8|location=Berkeley and Los Angeles, California|oclc=11754940|via=Google Books}}</ref> This strategy is made possible by the ] of all living organisms, and the conservation of ] and ] pathways and ] over the course of ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Allmon |first1=Warren D. |last2=Ross |first2=Robert M. |title=Evolutionary remnants as widely accessible evidence for evolution: the structure of the argument for application to evolution education |journal=Evolution: Education and Outreach |date=December 2018 |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=1 |doi=10.1186/s12052-017-0075-1 |s2cid=29281160 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Performing experiments in model organisms allows for better understanding the disease process without the added risk of harming an actual human. The species of the model organism is usually chosen so that it reacts to disease or its treatment in a way that resembles human ] as needed. ] in a model organism does not ensure an effect in humans, and care must be taken when generalizing from one organism to another.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Essential Developmental Biology|last=Slack|first=Jonathan M. W.|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|year=2013|location=Oxford|oclc=785558800}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2016}} However, many drugs, treatments and cures for human diseases are developed in part with the guidance of animal models.<ref name="zam">{{cite journal |last1=Chakraborty |first1=Chiranjib |last2=Hsu |first2=Chi |last3=Wen |first3=Zhi |last4=Lin |first4=Chang |last5=Agoramoorthy |first5=Govindasamy |title=Zebrafish: A Complete Animal Model for In Vivo Drug Discovery and Development |journal=Current Drug Metabolism |date=2009-02-01 |volume=10 |issue=2 |pages=116–124 |doi=10.2174/138920009787522197 |pmid=19275547 }}</ref><ref name=zrug>{{cite journal |last1=Kari |first1=G |last2=Rodeck |first2=U |last3=Dicker |first3=A P |title=Zebrafish: An Emerging Model System for Human Disease and Drug Discovery |journal=Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics |date=July 2007 |volume=82 |issue=1 |pages=70–80 |doi=10.1038/sj.clpt.6100223 |pmid=17495877 |s2cid=41443542 }}</ref> Treatments for animal diseases have also been developed, including for ],<ref name="buck1904"/> ],<ref name="buck1904" /> ],<ref name="buck1904" /> ] (FIV),<ref name="pu2005"/> ],<ref name="buck1904" /> Texas cattle fever,<ref name="buck1904" /> ] (hog cholera),<ref name="buck1904" /> ], and other ].<ref name="dryden2005"/> Animal experimentation continues to be required for biomedical research,<ref name=bundle/> and is used with the aim of solving medical problems such as Alzheimer's disease,<ref name="geula1998"/> AIDS,<ref name="AIDS2005"/> multiple sclerosis,<ref name="jameson1994"/> spinal cord injury, many headaches,<ref name="lyuksyutova1984"/> and other conditions in which there is no useful '']'' model system available. | |||

| The topic is highly controversial. Supporters of the practice, such as the British ], argue that virtually every medical achievement in the 20th century relied on the use of animals in some way,<ref name=TheRoyalSociety> ], 2004, page 1</ref> with the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research of the ] arguing that even sophisticated computers are unable to model interactions between molecules, cells, tissues, organs, organisms, and the environment, making animal research necessary in some areas.<ref>, Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, Published by the ] 2004; page 2 See also , ].</ref> Opponents, such as the ], question the necessity of it, arguing further that it is cruel, poor scientific practice, never reliably predictive of human metabolic and physiological specificities, poorly regulated, that the costs outweigh the alleged benefits, or that animals have an intrinsic right not to be used for experimentation.<ref> | |||

| **, ]; | |||

| The annual use of ] animals—from ] to non-human ]—was estimated at 192 million as of 2015.<ref name="Taylor Alvarez 2019 pp. 196–213">{{cite journal | last1=Taylor | first1=Katy | last2=Alvarez | first2=Laura Rego | title=An Estimate of the Number of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes Worldwide in 2015 | journal=Alternatives to Laboratory Animals | publisher=SAGE Publications | volume=47 | issue=5–6 | year=2019 | issn=0261-1929 | doi=10.1177/0261192919899853 | pages=196–213| pmid=32090616 | s2cid=211261775 | doi-access=free }}</ref> In the ], vertebrate species represent 93% of animals used in research,<ref name="Taylor Alvarez 2019 pp. 196–213">{{cite journal | last1=Taylor | first1=Katy | last2=Alvarez | first2=Laura Rego | title=An Estimate of the Number of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes Worldwide in 2015 | journal=Alternatives to Laboratory Animals | publisher=SAGE Publications | volume=47 | issue=5–6 | year=2019 | issn=0261-1929 | doi=10.1177/0261192919899853 | pages=196–213| pmid=32090616 | s2cid=211261775 | doi-access=free }}</ref> and 11.5 million animals were used there in 2011.<ref name="eurlex13">{{CELEX|52013DC0859|text=Seventh Report on the Statistics on the Number of Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes in the Member States of the European Union}}</ref> The mouse ('']'') is associated with many important biological discoveries of the 20th and 21st centuries,<ref name="Hedrich"/> and by one estimate, the number of mice and rats used in the United States alone in 2001 was 80 million.<ref name=Carbone26>Carbone, Larry. (2004). What Animals Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy.</ref> In 2013, it was reported that mammals (mice and rats), fish, amphibians, and reptiles together accounted for over 85% of research animals.<ref name="EUstatistics2013">{{cite web|title=EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers|url=http://speakingofresearch.com/2013/12/12/eu-statistics-show-decline-in-animal-research-numbers/|publisher=Speaking of Research|year=2013|access-date=24 January 2016}}</ref> In 2022, a law was passed in the United States that eliminated the ] requirement that all drugs be tested on animals.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://reason.com/2023/01/13/u-s-will-no-longer-require-animal-testing-for-new-drugs/|title=U.S. Will No Longer Require Animal Testing for New Drugs|date=13 January 2022}}</ref> | |||

| *, and , ]; | |||

| *, ]; | |||

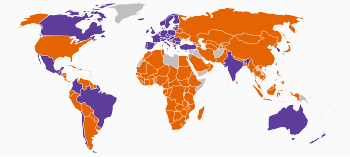

| Animal testing is regulated to varying degrees in different countries.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Festing |first1=Simon |last2=Wilkinson |first2=Robin |date=June 2007 |title=The ethics of animal research. Talking Point on the use of animals in scientific research |journal=EMBO Reports |volume=8 |issue=6 |pages=526–530 |doi=10.1038/sj.embor.7400993 |issn=1469-221X |pmc=2002542 |pmid=17545991}}</ref> Animal testing is regulated differently in different countries: in some cases it is strictly controlled while others have more relaxed regulations. There are ongoing debates about the ethics and necessity of animal testing. Proponents argue that it has led to significant advancements in medicine and other fields while opponents raise concerns about ] and question its effectiveness and reliability.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Reddy |first1=Navya |last2=Lynch |first2=Barry |last3=Gujral |first3=Jaspreet |last4=Karnik |first4=Kavita |date=September 2023 |title=Regulatory landscape of alternatives to animal testing in food safety evaluations with a focus on the western world |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37591329 |journal=Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology |volume=143 |pages=105470 |doi=10.1016/j.yrtph.2023.105470 |issn=1096-0295 |pmid=37591329|s2cid=260938742 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Petetta |first1=Francesca |last2=Ciccocioppo |first2=Roberto |date=November 2021 |title=Public perception of laboratory animal testing: Historical, philosophical, and ethical view |journal=Addiction Biology |volume=26 |issue=6 |pages=e12991 |doi=10.1111/adb.12991 |issn=1369-1600 |pmc=9252265 |pmid=33331099}}</ref> There are efforts underway to find alternatives to animal testing such as ], ] that mimics human organs for lab tests,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Low |first1=Lucie A. |last2=Mummery |first2=Christine |last3=Berridge |first3=Brian R. |last4=Austin |first4=Christopher P. |last5=Tagle |first5=Danilo A. |date=May 2021 |title=Organs-on-chips: into the next decade |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32913334 |journal=Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery |volume=20 |issue=5 |pages=345–361 |doi=10.1038/s41573-020-0079-3 |issn=1474-1784 |pmid=32913334|hdl=1887/3151779 |s2cid=221621465 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> microdosing techniques which involve administering small doses of test compounds to human volunteers instead of non-human animals for safety tests or drug screenings; ] (PET) scans which allow scanning of the human brain without harming humans; comparative epidemiological studies among human populations; simulators and computer programs for teaching purposes; among others.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Löwa |first1=Anna |last2=Jevtić |first2=Marijana |last3=Gorreja |first3=Frida |last4=Hedtrich |first4=Sarah |date=May 2018 |title=Alternatives to animal testing in basic and preclinical research of atopic dermatitis |journal=Experimental Dermatology |volume=27 |issue=5 |pages=476–483 |doi=10.1111/exd.13498 |issn=1600-0625 |pmid=29356091|s2cid=3378256 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Madden |first1=Judith C. |last2=Enoch |first2=Steven J. |last3=Paini |first3=Alicia |last4=Cronin |first4=Mark T. D. |date=July 2020 |title=A Review of In Silico Tools as Alternatives to Animal Testing: Principles, Resources and Applications |journal=Alternatives to Laboratory Animals: ATLA |volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=146–172 |doi=10.1177/0261192920965977 |issn=0261-1929 |pmid=33119417|s2cid=226204296 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Reddy |first1=Navya |last2=Lynch |first2=Barry |last3=Gujral |first3=Jaspreet |last4=Karnik |first4=Kavita |date=September 2023 |title=Alternatives to animal testing in toxicity testing: Current status and future perspectives in food safety assessments |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37453475 |journal=Food and Chemical Toxicology|volume=179 |pages=113944 |doi=10.1016/j.fct.2023.113944 |issn=1873-6351 |pmid=37453475|s2cid=259915886 }}</ref> | |||

| *Croce, Pietro. ''Vivisection or Science? An Investigation into Testing Drugs and Safeguarding Health''. Zed Books, 1999.</ref> | |||

| ==Definitions== | ==Definitions== | ||

| The terms |

The terms ''animal testing, animal experimentation, animal research'', '']'' testing, and ] have similar ]s but different ]s. Literally, "vivisection" means "live sectioning" of an animal, and historically referred only to experiments that involved the ] of live animals. The term is occasionally used to refer pejoratively to any experiment using living animals; for example, the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' defines "vivisection" as: "Operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals",<ref name=croce>Croce, Pietro (1999). ''Vivisection or Science? An Investigation into Testing Drugs and Safeguarding Health''. Zed Books, {{ISBN|1-85649-732-1}}.</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=https://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9382118?query=Vivisection&ct= |title=Vivisection |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080101153454/https://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9382118?query=Vivisection&ct= |archive-date=1 January 2008 |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |year=2007}}</ref><ref name=buavfaq>{{cite web |url=http://www.buav.org/pdf/VivisectionFAQs.pdf |title=Vivisection FAQ |publisher=British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150513021651/http://www.buav.org/pdf/VivisectionFAQs.pdf |archive-date=13 May 2015 }}</ref> although dictionaries point out that the broader definition is "used only by people who are opposed to such work".<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |entry=Vivisection |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia.com |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/divisions-diagnostics-and-procedures/medicine/vivisection#vivisection |access-date=2023-05-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |entry=Vivisection |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vivisection |access-date=2023-05-05 |dictionary=Merriam-Webster |language=en |title=Definition of VIVISECTION }}</ref> The word has a negative connotation, implying torture, suffering, and death.<ref name=Carbone22/> The word "vivisection" is preferred by those opposed to this research, whereas scientists typically use the term "animal experimentation".<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Paixão RL, Schramm FR | title = Ethics and animal experimentation: what is debated? | journal = Cadernos de Saúde Pública | volume = 15 | issue = Suppl 1 | pages = 99–110 | year = 1999 | pmid = 10089552 | doi=10.1590/s0102-311x1999000500011 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>Yarri, Donna (2005). ''The Ethics of Animal Experimentation'', Oxford University Press U.S., {{ISBN|0-19-518179-4}}.</ref> | ||

| <!--Create language section. Deborah Blum, Larry Carbone. Scientization.--> | |||

| The following text excludes as much as possible practices related to ''in vivo'' ], which is left to the discussion of ]. | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|History of animal testing}} | ||

| ]'', from 1768, by ]]] | |||

| ]’s dogs with a ] container and tube surgically implanted in his muzzle. Pavlov Museum, 2005]] | |||

| ]'s dogs with a ] container and tube surgically implanted in his muzzle, Pavlov Museum, 2005]] | |||

| ], from 1768, by Joseph Wright.]] | |||

| The earliest references to animal testing are found in the writings of the ] in the 2nd and 4th centuries BCE. ] and ] were among the first to perform experiments on living animals.<ref>Cohen and Loew 1984.</ref> ], a 2nd-century Roman physician, performed '']'' dissections of pigs and goats.<ref name=lpag>{{cite web|url=http://www.lpag.org/layperson/layperson.html#history |title=History of nonhuman animal research |publisher=Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061013110949/http://www.lpag.org/layperson/layperson.html |archive-date=13 October 2006 }}</ref> ], a 12th-century ] in ] introduced an experimental method of testing surgical procedures before applying them to human patients.<ref name=Rabie2005>{{cite journal | author = Abdel-Halim RE | title = Contributions of Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) to the progress of surgery: a study and translations from his book Al-Taisir | journal = Saudi Medical Journal | volume = 26 | issue = 9 | pages = 1333–39 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16155644 }}</ref><ref name=Rabie2006>{{cite journal | author = Abdel-Halim RE | title = Contributions of Muhadhdhab Al-Deen Al-Baghdadi to the progress of medicine and urology. A study and translations from his book Al-Mukhtar | journal = Saudi Medical Journal | volume = 27 | issue = 11 | pages = 1631–41 | year = 2006 | pmid = 17106533 }}</ref> Discoveries in the 18th and 19th centuries included ]'s use of a ] in a ] to prove that ] was a form of combustion, and ]'s demonstration of the ] in the 1880s using ] in sheep.<ref name="pmid11544370">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mock M, Fouet A | title = Anthrax | journal = Annu. Rev. Microbiol. | volume = 55 | pages = 647–71 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11544370 | doi = 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.647 }}</ref> ] used animal testing of mice and guinea pigs to discover the bacteria that cause anthrax and ]. In the 1890s, ] famously used dogs to describe ].<ref name="pmid3309839">{{cite journal | author = Windholz G | title = Pavlov as a psychologist. A reappraisal | journal = Pavlovian J. Biol. Sci. | volume = 22 | issue = 3 | pages = 103–12 | year = 1987 | doi = 10.1007/BF02734662 | pmid = 3309839 | s2cid = 141344843 }}</ref> | |||

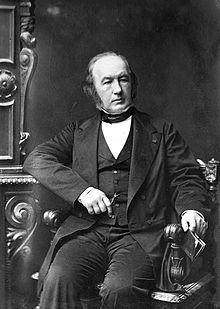

| ], regarded as the "prince of vivisectors"<ref name=Croce11/> and one of the greatest men of science, argued that experiments on animals are "entirely conclusive for the toxicology and hygiene of man,"<ref name=Bernard/> thereby establishing the paradigm still followed by the scientific community today.<ref name=Bernard>] ''An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine'', 1865. First English translation by Henry Copley Greene, published by Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1927; reprinted in 1949, p125</ref>]] | |||

| The earliest references to animal testing are found in the writings of the ] in the second and fourth centuries BCE. ] (Αριστοτέλης) (384-322 BCE) and ] (304-258 BCE) were among the first to perform experiments on living animals (Cohen and Loew 1984). ], a physician in second-century ], dissected pigs and goats, and is known as the "father of ]."<ref name=lpag>, Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group.</ref> | |||

| Research using animal models has been central to most of the achievements of modern medicine.<ref name=RSM2015>{{cite web| title = Statement of the Royal Society's position on the use of animals in research| author = Royal Society of Medicine| date = 13 May 2015| url = https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2015/animals-in-research/|quote=From antibiotics and insulin to blood transfusions and treatments for cancer or HIV, virtually every medical achievement in the past century has depended directly or indirectly on research using animals, including veterinary medicine.}}</ref><ref name=NRCIOM>{{cite book|author=] and ]|title=Use of Laboratory Animals in Biomedical and Behavioral Research|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EzorAAAAYAAJ|date=1988|publisher=National Academies Press|page=37|isbn=9780309038393|id=NAP:13195|quote=The...methods of scientific inquiry have greatly reduced the incidence of human disease and have substantially increased life expectancy. Those results have come largely through experimental methods based in part on the use of animals.}}</ref><ref name="Nature2007">{{cite journal |last1=Lieschke |first1=Graham J. |last2=Currie |first2=Peter D. |title=Animal models of human disease: zebrafish swim into view |journal=Nature Reviews Genetics |date=May 2007 |volume=8 |issue=5 |pages=353–367 |doi=10.1038/nrg2091 |pmid=17440532 |s2cid=13857842 |quote=Biomedical research depends on the use of animal models to understand the pathogenesis of human disease at a cellular and molecular level and to provide systems for developing and testing new therapies. }}</ref> It has contributed most of the basic knowledge in fields such as human ] and ], and has played significant roles in fields such as ] and ].<ref name=NRCIOMb>{{cite book|author=] and ]|title=Use of Laboratory Animals in Biomedical and Behavioral Research|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EzorAAAAYAAJ|date=1988|publisher=National Academies Press|page=27|isbn=9780309038393|id=NAP:13195|quote=Animal studies have been an essential component of every field of medical research and have been crucial for the acquisition of basic knowledge in biology.}}</ref><ref name="HLAS2011">Hau and Shapiro 2011: | |||

| Animals have played a role in numerous well-known experiments. In the 1880s, ] convincingly demonstrated the ] of medicine by giving ] to sheep. In the 1890s, ] famously used dogs to describe ]. ] was first isolated from dogs in 1922, and revolutionized the treatment of ]. On ], ] a Russian ], ], became the first of many ]. In the 1970s, ] multi-drug antibiotic treatments were developed first in ], then in humans. In 1996 ] was born, the first mammal to be ] from an adult cell. | |||

| * {{cite book|author1=Jann Hau|author2=Steven J. Schapiro|title=Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science, Volume I, Third Edition: Essential Principles and Practices|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=D-IHAaggi_4C|year=2011|publisher=CRC Press|page=2|isbn=978-1-4200-8456-6|quote=Animal-based research has played a key role in understanding infectious diseases, neuroscience, physiology, and toxicology. Experimental results from animal studies have served as the basis for many key biomedical breakthroughs.}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author1=Jann Hau|author2=Steven J. Schapiro|title=Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science, Volume II, Third Edition: Animal Models|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yk7TFvsFCBcC|year=2011|publisher=CRC Press|page=1|isbn=978-1-4200-8458-0|quote=Most of our basic knowledge of human biochemistry, physiology, endocrinology, and pharmacology has been derived from initial studies of mechanisms in animal models.}}</ref> For example, the results have included the near-] and the development of ], and have benefited both humans and animals.<ref name=RSM2015/><ref name="IOM1991">{{cite book|author=Institute of Medicine|title=Science, Medicine, and Animals|url=https://archive.org/details/sciencemedicinea00comm|url-access=registration|date=1991|publisher=National Academies Press|isbn=978-0-309-56994-1|page=|quote=...without this fundamental knowledge, most of the clinical advances described in these pages would not have occurred.}}</ref> From 1910 to 1927, ]'s work with the fruit fly '']'' identified ]s as the vector of inheritance for genes.<ref name="nobelprize.org">{{cite web|title=The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1933|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1933/index.html|access-date=2015-06-20|publisher=Nobel Web AB}}</ref><ref name="nobel2">{{cite web|title=Thomas Hunt Morgan and his Legacy|url=https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1933/morgan-article.html|access-date=2015-06-20|publisher=Nobel Web AB}}</ref> ''Drosophila'' became one of the first, and for some time the most widely used, model organisms,<ref>Kohler, ''Lords of the Fly'', chapter 5</ref> and ] wrote that Morgan's discoveries "helped transform biology into an experimental science".<ref name="Kandel1999">Kandel, Eric. 1999. , ''Columbia Magazine''</ref> ''D. melanogaster'' remains one of the most widely used eukaryotic model organisms. During the same time period, studies on mouse genetics in the laboratory of ] in collaboration with ] led to generation of the DBA ("dilute, brown and non-agouti") inbred mouse strain and the systematic generation of other inbred strains.<ref name="Steensma">{{cite journal|last=Steensma|first=David P. |author2=Kyle Robert A. |author3=Shampo Marc A.|date=November 2010|title=Abbie Lathrop, the "Mouse Woman of Granby": Rodent Fancier and Accidental Genetics Pioneer|journal=Mayo Clinic Proceedings|volume=85|issue=11|pmc=2966381|pmid=21061734|doi=10.4065/mcp.2010.0647|pages=e83}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://immunology.hms.harvard.edu/about-us/history|title=History of Immunology at Harvard|last=Pillai|first=Shiv|work=Harvard Medical School:About us|publisher=Harvard Medical School|access-date=19 December 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131220022416/https://immunology.hms.harvard.edu/about-us/history|archive-date=20 December 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> The mouse has since been used extensively as a model organism and is associated with many important biological discoveries of the 20th and 21st centuries.<ref name="Hedrich">{{cite book|title=The Laboratory Mouse|editor= Hedrich, Hans|publisher=Elsevier Science|chapter=The house mouse as a laboratory model: a historical perspective|isbn=9780080542539|date= 2004-08-21}}</ref> | |||

| In the late 19th century, ] isolated the ] toxin and demonstrated its effects in guinea pigs. He went on to develop an antitoxin against diphtheria in animals and then in humans, which resulted in the modern methods of immunization and largely ended diphtheria as a threatening disease.<ref name="nobel3"></ref> The diphtheria antitoxin is famously commemorated in the Iditarod race, which is modeled after the delivery of antitoxin in the ]. The success of animal studies in producing the diphtheria antitoxin has also been attributed as a cause for the decline of the early 20th-century opposition to animal research in the United States.<ref name="Cannon2009"> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090814184304/http://www.amphilsoc.org/library/mole/c/cannon.htm |date=14 August 2009 }}</ref> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| As the experimentation on animals increased, especially the practice of vivisection, so did criticism and controversy. In 1655, ] ] is recorded as saying that "the miserable torture of vivisection places the body in an unnatural state."<ref name=Ryder54>] ''Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes Towards Speciesism''. Berg Publishers, 2000, p. 54.</ref><ref name=ANZCCART>, Australian and New Zealand Council for the Care of Animals in Research and Teaching (ANZCCART), retrieved December 12, 2007, cites original reference in Maehle, A-H. and Tr6hler, U. 1987. Animal experimentation from antiquity to the | |||

| end of the eighteenth century: attitudes and arguments. In N. A. Rupke (ed.) Vivisection in Historical Perspective. Croom Helm, London, p. 22</ref> O'Meara and others argued that animal physiology could be affected by the pain and suffering of vivisection, rendering the results unreliable. There were also objections on an ] basis, contending that the benefit to humans did not justify the harm to animals.<ref name=ANZCCART/> Early objections to animal testing also came from another angle — many people believed that animals are inferior to humans and thus so different that any results obtained from animals would be inapplicable to humans.<ref name=ANZCCART/> | |||

| Subsequent research in model organisms led to further medical advances, such as ]'s research in dogs, which determined that the isolates of pancreatic secretion could be used to treat dogs with ]. This led to the 1922 discovery of ] (with ])<ref name="insulin"> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090930142937/http://www.mta.ca/faculty/arts/canadian_studies/english/about/study_guide/doctors/insulin.html |date=30 September 2009 }}</ref> and its use in treating diabetes, which had previously meant death.<ref name="Thompson2009"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090210030429/http://www.dlife.com/dLife/do/ShowContent/inspiration_expert_advice/famous_people/leonard_thompson.html |date=2009-02-10 }}</ref><ref name="pmid9285027">{{cite journal | author = Gorden P | title = Non-insulin dependent diabetes – the past, present and future | journal = Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. | volume = 26 | issue = 3 | pages = 326–30 | year = 1997 | pmid = 9285027 }}</ref> ]'s research in guinea pigs discovered the anticonvulsant properties of lithium salts,<ref> John Cade and Lithium</ref> which revolutionized the treatment of ], replacing the previous treatments of lobotomy or electroconvulsive therapy. Modern general anaesthetics, such as ] and related compounds, were also developed through studies on model organisms, and are necessary for modern, complex surgical operations.<ref name="raventos1956">Raventos J (1956) ''Br J Pharmacol'' 11, 394</ref><ref name="whalen2005">Whalen FX, Bacon DR & Smith HM (2005) ''Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol'' 19, 323</ref> | |||

| On the other side of the debate, those in favor of animal testing held that experiments on living animals were necessary to advance medical and biological knowledge. ], known as the "prince of vivisectors"<ref name=Croce11>Croce, Pietro. ''Vivisection or Science? An Investigation into Testing Drugs and Safeguarding Health''. Zed Books, 1999, p. 11.</ref> and the father of physiology, famously wrote in 1865 that "the science of life is a superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen".<ref name=TelegraphNov2003>, ''The Daily Telegraph, November 2003.<!--no day--></ref> Arguing that "experiments on animals ... are entirely conclusive for the toxicology and hygiene of man ... for as I have shown, the effects of these substances are the same on man as on animals, save for differences in degree,"<ref name=Bernard>] ''An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine'', 1865. First English translation by Henry Copley Greene, published by Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1927; reprinted in 1949, p125</ref> Bernard established the paradigm of animal experimentation in ] that is largely followed by the scientific community today.<ref name=LaFollette>LaFollette, H., Shanks, N., Animal Experimentation: the Legacy of Claude Bernard, ''International Studies in the Philosophy of Science'' (1994) pp. 195-210.</ref> Bernard's wife, Marie Françoise Martin, was a fervent anti-vivisectionist, and in 1883 founded the first anti-vivisection society in France.<ref name=Croce11/><ref>Rudacille, Deborah. ''The Scalpel and the Butterfly: The Conflict'', Farrar Straus Giroux, 2000, p. 19.</ref> | |||

| In the 1940s, ] used rhesus monkey studies to isolate the most virulent forms of the ] virus,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/05093/481117.stm |title=Developing a medical milestone: The Salk polio vaccine |access-date=2015-06-20 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100311191427/http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/05093/481117.stm |archive-date=2010-03-11 }} Virus-typing of polio by Salk</ref> which led to his creation of a ]. The vaccine, which was made publicly available in 1955, reduced the incidence of polio 15-fold in the United States over the following five years.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/05094/482468.stm |title=Tireless polio research effort bears fruit and indignation |access-date=2008-08-23 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080905022100/http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/05094/482468.stm |archive-date=2008-09-05 }} Salk polio virus</ref> ] improved the vaccine by passing the polio virus through animal hosts, including monkeys; the Sabin vaccine was produced for mass consumption in 1963, and had virtually eradicated polio in the United States by 1965.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110604021151/http://americanhistory.si.edu/polio/virusvaccine/vacraces2.htm|date=2011-06-04}} History of polio vaccine</ref> It has been estimated that developing and producing the vaccines required the use of 100,000 rhesus monkeys, with 65 doses of vaccine produced from each monkey. Sabin wrote in 1992, "Without the use of animals and human beings, it would have been impossible to acquire the important knowledge needed to prevent much suffering and premature death not only among humans, but also among animals."<ref></ref> | |||

| In 1822, the first ] was enacted in the ], followed by the ], the first law specifically aimed at regulating animal testing. The legislation was promoted by ], who wrote to ] in March 1871: "You ask about my opinion on vivisection. I quite agree that it is justifiable for real investigations on physiology; but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity. It is a subject which makes me sick with horror, so I will not say another word about it, else I shall not sleep to-night."<ref>, fullbooks.com</ref><ref>Bowlby, John. ''Charles Darwin: A New Life'', W. W. Norton & Company - 1991. p. 420</ref> | |||

| On 3 November 1957, a ], ], became the first of many ]. In the 1970s, antibiotic treatments and vaccines for ] were developed using armadillos,<ref name="pmid7242665">{{cite journal | author = Walgate R | title = Armadillos fight leprosy | journal = Nature | volume = 291 | issue = 5816 | page = 527 | year = 1981 | pmid = 7242665 | doi = 10.1038/291527a0 | bibcode = 1981Natur.291..527W | doi-access = free }}</ref> then given to humans.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, Krahenbuhl JL, Truman RW, Williams DL | title = The Continuing Challenges of Leprosy | journal = Clin. Microbiol. Rev. | volume = 19 | issue = 2 | pages = 338–81 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16614253 | pmc = 1471987 | doi = 10.1128/CMR.19.2.338-381.2006 }}</ref> The ability of humans to change the ] of animals took an enormous step forward in 1974 when ] could produce the first ], by integrating DNA from ] into the ] of mice.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jaenisch R, Mintz B | title = Simian Virus 40 DNA Sequences in DNA of Healthy Adult Mice Derived from Preimplantation Blastocysts Injected with Viral DNA | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 71 | issue = 4 | pages = 1250–54 | year = 1974 | pmid = 4364530 | pmc = 388203 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1250 | bibcode = 1974PNAS...71.1250J | doi-access = free }}</ref> This genetic research progressed rapidly and, in 1996, ] was born, the first mammal to be ] from an adult cell.<ref name=Wilmut/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.understandinganimalresearch.org.uk/resources/animal-research-essay-resources/history-of-animal-research/|title=History of animal research|website=www.understandinganimalresearch.org.uk|access-date=2016-04-08}}</ref> | |||

| The growing division between the pro- and anti- animal testing factions first came to dramatic public attention during the ] that raged in the early 1900s in the streets of ], when hundreds of medical students clashed with anti-vivisectionists and police over a memorial to a vivisected dog.<ref name=Mason>Mason, Peter. . Two Sevens Publishing, 1997.</ref><ref name=Grazter224>Gratzer, Walter. ''Eurekas and Euphorias: The Oxford Book of Scientific Anecdotes''. Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 224.</ref> | |||

| Other 20th-century medical advances and treatments that relied on research performed in animals include ] techniques,<ref name="carrel1912">Carrel A (1912) ''Surg. Gynec. Obst.'' 14: p. 246</ref><ref name="williamson1926">Williamson C (1926) ''J. Urol.'' 16: p. 231</ref><ref name="woodruff1986">Woodruff H & Burg R (1986) in ''Discoveries in Pharmacology'' vol 3, ed Parnham & Bruinvels, Elsevier, Amsterdam</ref><ref name="moore1964">Moore F (1964) ''Give and Take: the Development of Tissue Transplantation''. Saunders, New York</ref> the heart-lung machine,<ref name="gibbon1937">Gibbon JH (1937) ''Arch. Surg.'' 34, 1105</ref> ]s,<ref name="rawbw"> Hinshaw obituary</ref><ref name="fleming1929">Fleming A (1929) ''Br J Exp Path'' 10, 226</ref> and the ] vaccine.<ref name="mrc1956">Medical Research Council (1956) ''Br. Med. J.'' 2: p. 454</ref> Treatments for animal diseases have also been developed, including for ],<ref name="buck1904">''A reference handbook of the medical sciences''. William Wood and Co., 1904, Edited by Albert H. Buck.</ref> ],<ref name="buck1904" /> ],<ref name="buck1904" /> ] (FIV),<ref name="pu2005">{{cite journal |last1=Pu |first1=Ruiyu |last2=Coleman |first2=James |last3=Coisman |first3=James |last4=Sato |first4=Eiji |last5=Tanabe |first5=Taishi |last6=Arai |first6=Maki |last7=Yamamoto |first7=Janet K |title=Dual-subtype FIV vaccine (Fel-O-Vax® FIV) protection against a heterologous subtype B FIV isolate |journal=Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery |date=February 2005 |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=65–70 |doi=10.1016/j.jfms.2004.08.005 |pmid=15686976 |s2cid=26525327 |pmc=10911555 }}</ref> ],<ref name="buck1904" /> Texas cattle fever,<ref name="buck1904" /> ] (hog cholera),<ref name="buck1904" /> ], and other ].<ref name="dryden2005">{{cite journal | last1 = Dryden | first1 = MW | last2 = Payne | first2 = PA | title = Preventing parasites in cats | journal = Veterinary Therapeutics | volume = 6 | issue = 3 | pages = 260–7 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16299672 }}</ref> Animal experimentation continues to be required for biomedical research,<ref name=bundle>Sources: | |||

| ==Animals used== | |||

| * {{cite book|author=P. Michael Conn|title=Animal Models for the Study of Human Disease|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dVLVLIV8rD0C|date=29 May 2013|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=978-0-12-415912-9|page=37|quote=...animal models are central to the effective study and discovery of treatments for human diseases.}} | |||

| {{see also|Animal testing regulations}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Lieschke |first1=Graham J. |last2=Currie |first2=Peter D. |title=Animal models of human disease: zebrafish swim into view |journal=Nature Reviews Genetics |date=May 2007 |volume=8 |issue=5 |pages=353–367 |doi=10.1038/nrg2091 |pmid=17440532 |s2cid=13857842 |quote=Biomedical research depends on the use of animal models to understand the pathogenesis of human disease at a cellular and molecular level and to provide systems for developing and testing new therapies.}} | |||

| ===Numbers=== | |||

| * {{cite book|author1=Pierce K. H. Chow|author2=Robert T. H. Ng|author3=Bryan E. Ogden|title=Using Animal Models in Biomedical Research: A Primer for the Investigator|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NtWM8gD9Z2MC|year=2008|publisher=World Scientific|isbn=978-981-281-202-5|pages=1–2|quote=Arguments regarding whether biomedical science can advance without the use of animals are frequently mooted and make as much sense as questioning if clinical trials are necessary before new medical therapies are allowed to be widely used in the general population ...animal models are likely to remain necessary until science develops alternative models and systems that are equally sound and robust .}} | |||

| ]s used in animal testing in Europe in 2005: a total of 12.1 million animals were used.<ref name=EU2005/>]] | |||

| * {{cite book|author1=Jann Hau|author2=Steven J. Schapiro|title=Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science, Volume I, Third Edition: Essential Principles and Practices|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=D-IHAaggi_4C|year=2011|publisher=CRC Press|chapter=The contribution of laboratory animals to medical progress|isbn=978-1-4200-8456-6|quote=Animal models are required to connect in order to understand whole organisms, both in healthy and diseased states. In turn, these animal studies are required for understanding and treating human disease ...In many cases, though, there will be no substitute for whole-animal studies because of the involvement of multiple tissue and organ systems in both normal and aberrant physiological conditions .}} | |||

| Accurate global figures for animal testing are difficult to obtain. The ] (BUAV) estimates that 100 million vertebrates are experimented on around the world every year, 10–11 million of them in the European Union.<ref name=buavfaq>, British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.</ref> The Nuffield Council on Bioethics reports that global annual estimates range from 50 to 100 million animals. | |||

| * {{cite web| title = Statement of the Royal Society's position on the use of animals in research| author = Royal Society of Medicine| date = 24 May 2023| url = https://royalsociety.org/about-us/what-we-do/supporting-researchers/animal-testing/|quote=At present the use of animals remains the only way for some areas of research to progress.}}</ref> and is used with the aim of solving medical problems such as Alzheimer's disease,<ref name="geula1998">{{cite journal |last1=Guela |first1=Changiz |last2=Wu |first2=Chuang-Kuo |last3=Saroff |first3=Daniel |last4=Lorenzo |first4=Alfredo |last5=Yuan |first5=Menglan |last6=Yankner |first6=Bruce A. |title=Aging renders the brain vulnerable to amyloid β-protein neurotoxicity |journal=Nature Medicine |date=July 1998 |volume=4 |issue=7 |pages=827–831 |doi=10.1038/nm0798-827 |pmid=9662375 |s2cid=45108486 }}</ref> AIDS,<ref name="AIDS2005"> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081217131711/http://www.aidsreviews.com/files/2005_7_2_67_83.pdf |date=17 December 2008 }}</ref><ref></ref><ref></ref> multiple sclerosis,<ref name="jameson1994">{{cite journal |last1=Jameson |first1=Bradford A. |last2=McDonnell |first2=James M. |last3=Marini |first3=Joseph C. |last4=Korngold |first4=Robert |title=A rationally designed CD4 analogue inhibits experimental allergic encephalomyelitis |journal=Nature |date=April 1994 |volume=368 |issue=6473 |pages=744–746 |doi=10.1038/368744a0 |pmid=8152486 |bibcode=1994Natur.368..744J |s2cid=4370797 }}</ref> spinal cord injury, many headaches,<ref name="lyuksyutova1984">{{cite journal | last1 = Lyuksyutova | first1 = AL | last2 = Lu C-C | first2 = Milanesio N | year = 2003 | title = Anterior-posterior guidance of commissural axons by Wnt-Frizzled signaling | journal = Science | volume = 302 | issue = 5652| doi=10.1126/science.1089610 | pmid=14671310 | last3 = Milanesio | first3 = N | last4 = King | first4 = LA | last5 = Guo | first5 = N | last6 = Wang | first6 = Y | last7 = Nathans | first7 = J | last8 = Tessier-Lavigne | first8 = M | last9 = Zou | first9 = Y | display-authors = 8| pages = 1984–8| bibcode = 2003Sci...302.1984L | s2cid = 39309990 }}</ref> and other conditions in which there is no useful '']'' model system available. | |||

| ] testing became important in the 20th century. In the 19th century, laws regulating drugs were more relaxed. For example, in the US, the government could only ban a drug after they had prosecuted a company for selling products that harmed customers. However, in response to the ] of 1937 in which the eponymous drug killed over 100 users, the US Congress passed laws that required safety testing of drugs on animals before they could be marketed. Other countries enacted similar legislation.<ref name=afda>{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/ProductRegulation/SulfanilamideDisaster/default.htm |title=Taste of Raspberries, Taste of Death. The 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide Incident|work= FDA Consumer magazine |date=June 1981 }}</ref> In the 1960s, in reaction to the ] tragedy, further laws were passed requiring safety testing on pregnant animals before a drug can be sold.<ref name =Burkholz>{{cite news| first =Herbert | last =Burkholz | title = Giving Thalidomide a Second Chance | url =https://www.fda.gov/fdac/features/1997/697_thal.html | work =FDA Consumer | publisher =US ] | date =1 September 1997}}</ref> | |||

| None of the figures, including those given in this article, include invertebrates, such as shrimp and fruit flies.<ref name=nuffield45>, Nuffield Council on Bioethics, section 1.6.</ref> Animals bred for research then killed as surplus, animals used for breeding purposes, and animals not yet weaned (which most laboratories do not count)<ref name=Carbone26>Carbone, Larry. '"What Animal Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy''. Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 26.</ref> are also not included in the figures. | |||

| ==Model organisms== | |||

| According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the total number of animals used in that country in 2005 was almost 1.2 million, not including rats, mice, birds, fish, or frogs, which jointly make up 85% of research animals.<ref></ref><ref></ref><ref>Science Magazine, Trull and Rich 1999 Vol. 284. no. 5419, p. 1463.</ref> The Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group has used the USDA's figures to estimate that 23-25 million vertebrate animals are used in research each year in America. In 1995, researchers at Tufts University Center for Animals and Public Policy estimated that 14-21 million animals were used in American laboratories in 1992, a reduction from a high of 50 million used in 1970.<ref>Rowan, Loew, and Weer 1995<!--will supply full details later-->cited in Carbone 2004, p. 26.</ref> In 1986, the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment reported that estimates of the animals used in the U.S. range from 10 million to upwards of 100 million each year, and that their own best estimate was at least 17 million to 22 million.<ref>''Alternatives to Animal Use in Research, Testing and Education'', U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment, Washington, D.C.:Government Printing Office, 1986, p. 64. In 1966, the Laboratory Animal Breeders Association estimated in testimony before Congress that the number of mice, rats, guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits used in 1965 was around 60 million. (Hearings before the Subcommittee on Livestock and Feed Grains, Committee on Agriculture, U.S. House of Representatives, 1966, p. 63.) In 2004, the Department of Agriculture listed 64,932 dogs, 23,640 cats, 54,998 non-human primates, 244,104 guinea pigs, 175,721 hamsters, 261,573 rabbits, 105,678 farm animals, and 171,312 other mammals, a total of 1,101,958, a figure that includes all mammals except purpose-bred mice and rats. The use of dogs and cats in research in the U.S. decreased from 1973 to 2004 from 195,157 to 64,932, and from 66,165 to 23,640, respectively. ()</ref> | |||

| {{main|Model organism}} | |||

| ===Invertebrates=== | |||

| {{Main|Animal testing on invertebrates}} | |||

| {{See also|Pain in invertebrates}} | |||

| ] are an invertebrate commonly used in animal testing.]] | |||

| Although many more invertebrates than vertebrates are used in animal testing, these studies are largely unregulated by law. The most frequently used invertebrate species are '']'', a fruit fly, and '']'', a ] worm. In the case of ''C. elegans'', the worm's body is completely transparent and the precise lineage of all the organism's cells is known,<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Antoshechkin I, Sternberg PW | title = The versatile worm: genetic and genomic resources for Caenorhabditis elegans research | journal = Nature Reviews Genetics | volume = 8 | issue = 7 | pages = 518–32 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17549065 | doi = 10.1038/nrg2105 | s2cid = 12923468 }}</ref> while studies in the fly ''D. melanogaster'' can use an amazing array of genetic tools.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Matthews KA, Kaufman TC, Gelbart WM | title = Research resources for Drosophila: the expanding universe | journal = Nature Reviews Genetics | volume = 6 | issue = 3 | pages = 179–93 | year = 2005 | pmid = 15738962 | doi = 10.1038/nrg1554 | s2cid = 31002250 }}</ref> These invertebrates offer some advantages over vertebrates in animal testing, including their short life cycle and the ease with which large numbers may be housed and studied. However, the lack of an adaptive ] and their simple organs prevent worms from being used in several aspects of medical research such as vaccine development.<ref name=Schulenburg>{{cite journal |vauthors=Schulenburg H, Kurz CL, Ewbank JJ | title = Evolution of the innate immune system: the worm perspective | journal = Immunological Reviews | volume = 198 | pages = 36–58 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15199953 | doi = 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0125.x | s2cid = 21541043 }}</ref> Similarly, the fruit fly ] differs greatly from that of humans,<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Leclerc V, Reichhart JM | title = The immune response of Drosophila melanogaster | journal = Immunological Reviews | volume = 198 | pages = 59–71 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15199954 | doi = 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0130.x | s2cid = 7395057 }}</ref> and diseases in insects can be different from diseases in vertebrates;<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Mylonakis E, Aballay A | title = Worms and flies as genetically tractable animal models to study host-pathogen interactions | journal = Infection and Immunity | volume = 73 | issue = 7 | pages = 3833–41 | year = 2005 | pmid = 15972468 | pmc = 1168613 | doi = 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3833-3841.2005 }}</ref> however, fruit flies and ] can be useful in studies to identify novel virulence factors or pharmacologically active compounds.<ref name="ncbi.nlm.nih.gov">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kavanagh K, Reeves EP | title = Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens | journal = FEMS Microbiology Reviews | volume = 28 | issue = 1 | pages = 101–12 | year = 2004 | pmid = 14975532 | doi = 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.002 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="plosone.org">{{cite journal | vauthors = Antunes LC, Imperi F, Carattoli A, Visca P | title = Deciphering the Multifactorial Nature of Acinetobacter baumannii Pathogenicity | journal = PLOS ONE| volume = 6 | issue = 8 | pages = e22674 | year = 2011 | pmid = 21829642 | pmc = 3148234 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0022674 | editor1-last = Adler | editor1-first = Ben |bibcode = 2011PLoSO...622674A | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="Aperis G 2011">{{cite journal |vauthors=Aperis G, Fuchs BB, Anderson CA, Warner JE, Calderwood SB, Mylonakis E | title = Galleria mellonella as a model host to study infection by the Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain | journal = Microbes and Infection / Institut Pasteur | volume = 9 | issue = 6 | pages = 729–34 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17400503 | pmc = 1974785 | doi = 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.02.016 }}</ref> | |||

| Several invertebrate systems are considered acceptable alternatives to vertebrates in early-stage discovery screens.<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Waterfield NR, Sanchez-Contreras M, Eleftherianos I, Dowling A, Yang G, Wilkinson P, Parkhill J, Thomson N, Reynolds SE, Bode HB, Dorus S, Ffrench-Constant RH |doi=10.1073/pnas.0711114105|title=Rapid Virulence Annotation (RVA): Identification of virulence factors using a bacterial genome library and multiple invertebrate hosts|year=2008|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=105|issue=41|pages=15967–72 |bibcode = 2008PNAS..10515967W |pmid=18838673 |pmc=2572985|doi-access=free}}</ref> Because of similarities between the innate immune system of insects and mammals, insects can replace mammals in some types of studies. ''Drosophila melanogaster'' and the '']'' waxworm have been particularly important for analysis of virulent traits of mammalian pathogens.<ref name="ncbi.nlm.nih.gov"/><ref name="plosone.org"/> Waxworms and other insects have also proven valuable for the identification of pharmaceutical compounds with favorable bioavailability.<ref name="Aperis G 2011"/> The decision to adopt such models generally involves accepting a lower degree of biological similarity with mammals for significant gains in experimental throughput. | |||

| In the UK, Home Office figures show that nearly three million procedures were carried out in 2004 on just under the same number of animals.<ref name=GB14>, Great Britain, 2004, p. 14.</ref> It is the third consecutive annual rise and the highest figure since 1992.<ref>Jha, Alok. , ''The Guardian'', December 9, 2005.</ref> Most animals are used in only one procedure: animals either die because of the experiment or are euthanized afterwards.<ref name=GB14/><ref name=nuffield45/> A "procedure" refers to an experiment that might last minutes, several months, or years. | |||

| ===Rodents=== | |||

| <table style="float" align="left"> | |||

| {{main|Animal testing on rodents}} | |||

| <tr><td> | |||

| {{also|Median lethal dose}} | |||

| ] are commonly used.]] | |||

| ]. The water is within 1 cm of the small flower pot bottom platform where the rat sits. The rat is able to sleep but at the onset of REM sleep muscle tone is lost and the rat would either fall into the water only to clamber back to the pot to avoid drowning, or its ] would become submerged into the water ] it back to an awakened state.]]In the U.S., the numbers of rats and mice used is estimated to be from 11 million<ref name=USDA2016 /> to between 20 and 100 million a year.<ref name="Trull">{{cite journal|last1=Trull|first1=F. L.|year=1999|title=More Regulation of Rodents|journal=Science|volume=284|issue=5419|page=1463|bibcode=1999Sci...284.1463T|doi=10.1126/science.284.5419.1463|pmid=10383321|s2cid=10122407}}</ref> Other rodents commonly used are guinea pigs, hamsters, and gerbils. Mice are the most commonly used vertebrate species because of their size, low cost, ease of handling, and fast reproduction rate.<ref name=Rosenthal>{{cite journal |vauthors=Rosenthal N, Brown S | title = The mouse ascending: perspectives for human-disease models | journal = Nature Cell Biology | volume = 9 | issue = 9 | pages = 993–99 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17762889 | doi = 10.1038/ncb437 | s2cid = 4472227 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Mukerjee|first1=M|title=Speaking for the Animals|journal=Scientific American|date=August 2004|volume=291|issue=2|pages=96–97|doi=10.1038/scientificamerican0804-96|bibcode=2004SciAm.291b..96M}}</ref> Mice are widely considered to be the best model of ] and share 95% of their ]s with humans.<ref name=Rosenthal/> With the advent of ] technology, genetically modified mice can be generated to order and can provide models for a range of human diseases.<ref name=Rosenthal/> Rats are also widely used for physiology, toxicology and cancer research, but genetic manipulation is much harder in rats than in mice, which limits the use of these rodents in basic science.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Aitman TJ, Critser JK, Cuppen E, Dominiczak A, Fernandez-Suarez XM, Flint J, Gauguier D, Geurts AM, Gould M, Harris PC, Holmdahl R, Hubner N, Izsvák Z, Jacob HJ, Kuramoto T, Kwitek AE, Marrone A, Mashimo T, Moreno C, Mullins J, Mullins L, Olsson T, Pravenec M, Riley L, Saar K, Serikawa T, Shull JD, Szpirer C, Twigger SN, Voigt B, Worley K | title = Progress and prospects in rat genetics: a community view | journal = Nature Genetics | volume = 40 | issue = 5 | pages = 516–22 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18443588 | doi = 10.1038/ng.147 | s2cid = 22522876 }}</ref> | |||

| </td></tr> | |||

| <tr><td> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| </td></tr> | |||

| <tr><td> | |||

| ] inside ]. ]] | |||

| </td></tr> | |||

| <tr><td> | |||

| ] | |||

| </td></tr> | |||

| </table> | |||

| === |

===Dogs=== | ||

| {{See also|Laika|Soviet space dogs}}{{anchor|Cats and dogs}} | |||

| *;Invertebrates | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Animal testing on invertebrates}} | |||

| Dogs are widely used in biomedical research, testing, and education—particularly ]s, because they are gentle and easy to handle, and to allow for comparisons with historical data from beagles (a Reduction technique).<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Taylor |first1=Katy |last2=Alvarez |first2=Laura Rego |date=November 2019 |title=An Estimate of the Number of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes Worldwide in 2015 |journal=Alternatives to Laboratory Animals |volume=47 |issue=5–6 |pages=196–213 |doi=10.1177/0261192919899853 |pmid=32090616 |s2cid=211261775 |issn=0261-1929|doi-access=free }}</ref> They are used as models for human and veterinary diseases in cardiology, ], and bone and joint studies, research that tends to be highly invasive, according to the ].<ref name="HSUSDogs">, The Humane Society of the United States</ref> The most common use of dogs is in the safety assessment of new medicines<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Smith|first1=D|last2=Broadhead|first2=C|last3=Descotes|first3=G|last4=Fosse|first4=R|last5=Hack|first5=R|last6=Krauser|first6=K|last7=Pfister|first7=R|last8=Phillips|first8=B|last9=Rabemampianina|first9=Y|last10=Sanders|first10=J|last11=Sparrow|first11=S|last12=Stephan-Gueldner|first12=M|last13=Jacobsen|first13=SD|date=2002|title=Preclinical Safety Evaluation Using Nonrodent Species: An Industry/ Welfare Project to Minimize Dog Use|journal=ILAR|volume=43 Suppl|pages=S39-42|doi=10.1093/ilar.43.Suppl_1.S39|pmid=12388850|doi-access=free}}</ref> for human or veterinary use as a second species following testing in rodents, in accordance with the regulations set out in the ]. One of the most significant advancements in medical science involves the use of dogs in developing the answers to insulin production in the body for diabetics and the role of the pancreas in this process. They found that the pancreas was responsible for producing insulin in the body and that removal of the pancreas, resulted in the development of diabetes in the dog. After re-injecting the pancreatic extract (insulin), the blood glucose levels were significantly lowered.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Quianzon|first1=Celeste C.|last2=Cheikh|first2=Issam|date=2012-07-16|title=History of insulin|journal=Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives|volume=2|issue=2|pages=18701|doi=10.3402/jchimp.v2i2.18701|issn=2000-9666|pmc=3714061|pmid=23882369}}</ref> The advancements made in this research involving the use of dogs has resulted in a definite improvement in the quality of life for both humans and animals.{{Citation needed|date=February 2024}} | |||

| Although much larger numbers of invertebrates than vertebrates are used, these experiments are largely unregulated by law and are therefore not included in statistics. The most used invertebrate species are '']'', a fruit fly, and '']'', a ] worm. In the case of ''C. elegans'', the precise lineage of all the organism's cells is known, and ''D. melanogaster'' is very well-suited to genetic studies.<ref name=Schulenburg>Schulenburg, H., Kurz, C.L., Ewbank, J.J. "Evolution of the innate immune system: the worm perspective," Immunol. Rev., volume 198, pp. 36-58, 2004. pmid 15199953</ref> These animals offer great advantages over vertebrates, including their short life cycle and the ease with which large numbers may be studied, with thousands of flies or nematodes fitting into a single room. However, the lack of an adaptive ] and their simple organs prevents worms from being used in medical research such as vaccine development.<ref name=Schulenburg/> Similarly, flies are not widely used in applied medical research, as their ] differs greatly from that of humans,<ref>Leclerc V, Reichhart JM. "The immune response of Drosophila melanogaster," ''Immunol. Rev.''. volume 198, pp. 59-71, 2004. pmid 15199954</ref> and diseases in insects can be very different from diseases in more complex animals.<ref>Mylonakis E., Aballay A. , ''Infect. Immun.'', volume 73, issue 7, pp. 3833-41, 2005. pmid 15972468</ref> | |||

| The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal Welfare Report shows that 60,979 dogs were used in USDA-registered facilities in 2016.<ref name=USDA2016 /> In the UK, according to the UK Home Office, there were 3,847 procedures on dogs in 2017.<ref name=UK2017/> Of the other large EU users of dogs, Germany conducted 3,976 procedures on dogs in 2016<ref>{{cite web|url=https://speakingofresearch.com/2018/02/06/germany-sees-7-rise-in-animal-research-procedures-in-2016/|title=Germany sees 7% rise in animal research procedures in 2016|date=6 February 2018|publisher=Speaking of Research}}</ref> and France conducted 4,204 procedures in 2016.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://speakingofresearch.com/2018/03/20/france-italy-and-the-netherlands-publish-their-2016-statistics/#France|title=France, Italy and the Netherlands publish their 2016 statistics|date=20 March 2018|publisher=Speaking of Research}}</ref> In both cases this represents under 0.2% of the total number of procedures conducted on animals in the respective countries. | |||

| *;Rodents, fish, and rabbits | |||

| {{main|Animal testing on rodents|Draize test}} | |||

| In the U.S., the numbers of rats and mice used is estimated at 15-20 million a year.<ref> Foundation for Biomedical Research, Accessed 06 September 2007</ref> Other rodents commonly used are guinea pigs, hamsters, and gerbils. Mice are the most commonly used vertebrate species because of their size, low cost, ease of handling, and fast reproduction rate.<ref name=Rosenthal>Rosenthal N, Brown S. "The mouse ascending: perspectives for human-disease models," Nat. Cell Biol, Volume 9, issue 9, pp. 993-9, 2007. pmid 17762889</ref> Mice are widely considered to be the best model of ] and share 99% of their ]s with humans.<ref name=Sanger>, Sanger Institute Press Release, 5 December 2002</ref><ref name=Rosenthal/> With the advent of ] technology, genetically modified mice can be generated to order and can cost hundreds of dollars each.<ref name=Taconic>, Taconic Farms, Inc.</ref> | |||

| === Zebrafish === | |||

| Nearly 200,000 fish and 20,000 amphibians were used in the UK in 2004.<ref name=HomeOffice2004> , British government.</ref> The main species used is the zebrafish, '']'', which are translucent during their embryonic stage, and the African clawed frog, '']''. Over 20,000 rabbits were used for animal testing in the UK in 2004.<ref name=HomeOffice2004/> ] rabbits are used in eye irritancy tests because rabbits have less tear flow than other animals, and the lack of eye pigment make the effects easier to visualize.<ref name=HomeOffice2004/> | |||

| ] are commonly used for the basic study and development of various ]s. Used to explore the immune system and genetic strains. They are low in cost, small in size, have a fast reproduction rate, and able to observe cancer cells in real time. Humans and zebrafish share ] similarities which is why they are used for research. The National Library of Medicine shows many examples of the types of cancer zebrafish are used in. The use of zebrafish have allowed them to find differences between MYC-driven pre-B vs T-ALL and be exploited to discover novel pre-B ALL therapies on acute lymphocytic ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Li |first1=Zhitao |last2=Zheng |first2=Wubin |last3=Wang |first3=Hanjin |last4=Cheng |first4=Ye |last5=Fang |first5=Yijiao |last6=Wu |first6=Fan |last7=Sun |first7=Guoqiang |last8=Sun |first8=Guangshun |last9=Lv |first9=Chengyu |last10=Hui |first10=Bingqing |date=2021-03-15 |title=Application of Animal Models in Cancer Research: Recent Progress and Future Prospects |journal=Cancer Management and Research |volume=13 |pages=2455–2475 |doi=10.2147/CMAR.S302565 |issn=1179-1322 |pmc=7979343 |pmid=33758544 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Workman |first1=P. |last2=Aboagye |first2=E. O. |last3=Balkwill |first3=F. |last4=Balmain |first4=A. |last5=Bruder |first5=G. |last6=Chaplin |first6=D. J. |last7=Double |first7=J. A. |last8=Everitt |first8=J. |last9=Farningham |first9=D. a. H. |last10=Glennie |first10=M. J. |last11=Kelland |first11=L. R. |date=2010-05-25 |title=Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research |journal=British Journal of Cancer |volume=102 |issue=11 |pages=1555–1577 |doi=10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642 |issn=1532-1827 |pmc=2883160 |pmid=20502460}}</ref> | |||

| The National Library of Medicine also explains how a neoplasm is difficult to diagnose at an early stage. Understanding the molecular mechanism of digestive tract tumorigenesis and searching for new treatments is the current research. Zebrafish and humans share similar gastric cancer cells in the gastric cancer xenotransplantation model. This allowed researchers to find that Triphala could inhibit the growth and metastasis of gastric cancer cells. Since zebrafish liver cancer genes are related with humans they have become widely used in liver cancer search, as will as many other cancers.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tsering |first1=Jokyab |last2=Hu |first2=Xianda |date=2018 |title=Triphala Suppresses Growth and Migration of Human Gastric Carcinoma Cells In Vitro and in a Zebrafish Xenograft Model |journal=BioMed Research International |volume=2018 |pages=7046927 |doi=10.1155/2018/7046927 |issn=2314-6141 |pmc=6311269 |pmid=30643816|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| *;Cats and dogs | |||

| {{see also|Laika|Russian space dogs}} | |||

| Cats are most commonly used in neurological research. Over 25,500 cats were used in the U.S. in 2000, around half of whom were used in experiments that caused "pain and/or distress".<ref> AAVS newsletter Winter 2003</ref> | |||

| ] are a freshwaterfish and belong to the minnow family. They are commonly used for cancer research.]] | |||

| Dogs are widely used in biomedical research, testing, and education — particularly beagles, because they are gentle and easy to handle. They are commonly used as models for human diseases in cardiology, endocrinology, and bone and joint studies, research that tends to be highly invasive, according to the ].<ref name=HSUSDogs>, The Humane Society of the United States.</ref> The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal Welfare Report for 2004 shows that nearly 65,000 dogs were used in USDA-registered facilities in that year.<ref>The USDA figures are cited in , The Humane Society of the United States.</ref> In the U.S., some of the dogs are purpose-bred, while most are supplied by so-called Class B dealers licensed by the USDA to buy animals from auctions, shelters, newspaper ads, and who are sometimes accused of ].<ref name=Gillham>Gillham, Christina. , ''Newsweek'', February 17, 2006.</ref> | |||

| ===Non-human primates=== | |||

| {{ |

{{Main|Animal testing on non-human primates}} | ||

| ], the third primate to orbit the Earth, before insertion into the ] capsule in 1961]] | |||

| Non-human primates (NHPs) are used in toxicology tests, studies of AIDS and hepatitis, studies of ], behavior and cognition, reproduction, ], and ]. They are caught in the wild, taken from zoos, circuses and animal trainers, or purpose-bred.<ref name=OverviewR&R>, Project R&R, New England Anti-Vivisection Society.</ref> The primates used in the USA, China, and Europe are mostly purpose-bred. In the U.S. and China, most primates are domestically purpose-bred, whereas in Europe the majority are imported purpose-bred.<ref>, Proceedings of the Workshop Held April 17-19, pages 36-45, 46-48, 63-69, 197-200.</ref> Rhesus monkeys, cynomolgus monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and owl monkeys are imported; around 12,000 to 15,000 monkeys are imported into the U.S. annually.<ref></ref> Around 65,000 NHPs are used each year in the United States and European Union.<ref>, p. 10.</ref><ref name=buavprimates> , British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.</ref><ref name=jha>Jha, Alok. , ''The Guardian'', December 9, 2005.</ref> Most of the NHPs used are ]s;<ref name="Humaneprimate">, Conlee, ''et al'', Proceedings of the Fourth World Congress, accessed August 29, 2007.</ref> but ]s, ]s, and ]s are also used, and ]s and ]s are used in the U.S; there are currently 1133 chimpanzees in U.S. research laboratories.<ref></ref> Notable studies on non-human primates have been part of the polio vaccine development, and development of ], and their current heaviest non-toxicological use occurs in the monkey AIDS model, ].<ref></ref><ref> (Overview of development of DBS in Parkinson's) at "The Parkinson's Appeal for Deep Brain Simulation", http://www.parkinsonsappeal.com.</ref><ref></ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Non-human primates (NHPs) are used in toxicology tests, studies of AIDS and hepatitis, studies of ], behavior and cognition, reproduction, ], and ]. They are caught in the wild or purpose-bred. In the United States and China, most primates are domestically purpose-bred, whereas in Europe the majority are imported purpose-bred.<ref>, Proceedings of the Workshop Held 17–19 April, pp. 36–45, 46–48, 63–69, 197–200.</ref> The ] reported that in 2011, 6,012 monkeys were experimented on in European laboratories.<ref name="eurlex13"/> According to the ], there were 71,188 monkeys in U.S. laboratories in 2016.<ref name=USDA2016 /> 23,465 monkeys were imported into the U.S. in 2014 including 929 who were caught in the wild.<ref>{{cite web|title=U.S. primate import statistics for 2014|url=http://www.ippl.org/gibbon/2015/01/|website=International Primate Protection League|access-date=9 July 2015|archive-date=4 July 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170704090032/https://www.ippl.org/gibbon/2015/01/}}</ref> Most of the NHPs used in experiments are ]s;<ref name="Humaneprimate"/> but ]s, ]s, and ]s are also used, and ]s and ]s are used in the US. {{as of|2015}}, there are approximately 730 chimpanzees in U.S. laboratories.<ref>{{cite news|last1=St. Fleur|first1=Nicholas|title=U.S. Will Call All Chimps 'Endangered'|work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/13/science/chimpanzees-endangered-fish-and-wildlife-service.html|access-date=9 July 2015|agency=The New York Times|date=12 June 2015}}</ref> | |||

| In a survey in 2003, it was found that 89% of singly-housed primates exhibited self-injurious or ] ]ical behaviors including pacing, rocking, hair pulling, and biting among others.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Lutz|first1=C|last2=Well|first2=A|last3=Novak|first3=M|title=Stereotypic and Self-Injurious Behavior in Rhesus Macaques: A Survey and Retrospective Analysis of Environment and Early Experience|journal=American Journal of Primatology|date=2003|volume=60|issue=1|pages=1–15|doi=10.1002/ajp.10075|pmid=12766938|s2cid=19980505}}<!--|access-date=9 July 2015--></ref> | |||

| The first transgenic primate was produced in 2001, with the development of a method that could introduce new genes into a ].<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Chan AW, Chong KY, Martinovich C, Simerly C, Schatten G | title = Transgenic monkeys produced by retroviral gene transfer into mature oocytes | journal = Science | volume = 291 | issue = 5502 | pages = 309–12 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11209082 | doi = 10.1126/science.291.5502.309 | bibcode = 2001Sci...291..309C }}</ref> This transgenic technology is now being applied in the search for a treatment for the ] ].<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Yang SH, Cheng PH, Banta H, Piotrowska-Nitsche K, Yang JJ, Cheng EC, Snyder B, Larkin K, Liu J, Orkin J, Fang ZH, Smith Y, Bachevalier J, Zola SM, Li SH, Li XJ, Chan AW | title = Towards a transgenic model of Huntington's disease in a non-human primate | journal = Nature | volume = 453 | issue = 7197 | pages = 921–24 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18488016 | pmc = 2652570 | doi = 10.1038/nature06975 | bibcode = 2008Natur.453..921Y }}</ref> Notable studies on non-human primates have been part of the polio vaccine development, and development of ], and their current heaviest non-toxicological use occurs in the monkey AIDS model, ].<ref name=TheRoyalSociety/><ref name="Humaneprimate">{{cite web | first1=Kathleen M. | last1=Conlee | first2=Erika H. | last2=Hoffeld | first3=Martin L. | last3=Stephens | year=2004 | archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080227041442/http://www.worldcongress.net/2002/proceedings/C2%20Conlee.pdf | archivedate=27 February 2008 | url=http://www.worldcongress.net/2002/proceedings/C2%20Conlee.pdf | title=Demographic Analysis of Primate Research in the United States | work=ATLA | volume=32 | issue=Supplement 1 | pages=315–22}}</ref><ref name=Emborg/> In 2008, a proposal to ban all primates experiments in the EU has sparked a vigorous debate.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2008/nov/02/primate-monkey-animal-testing-drugs|title=Ban on primate experiments would be devastating, scientists warn|work=]|date=2 November 2008|first=Robin|last=McKie|location=London}}</ref> | |||

| ===Other species=== | |||

| {{Further|Animal testing on frogs|Animal testing on rabbits|Draize test}} | |||

| Over 500,000 fish and 9,000 amphibians were used in the UK in 2016.<ref name=UK2017>{{cite web|url=https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/724611/annual-statistics-scientific-procedures-living-animals-2017.pdf |title=Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain|year= 2017|work= UK Home Office |access-date=2018-07-23}}</ref> The main species used is the zebrafish, '']'', which are translucent during their embryonic stage, and the African clawed frog, '']''. Over 20,000 rabbits were used for animal testing in the UK in 2004.<ref name=HomeOffice2004>{{cite web|url=http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm67/6713/6713.pdf |title=Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain|year= 2004|work= British government |access-date=2012-07-13}}</ref> ] rabbits are used in eye irritancy tests (]) because rabbits have less tear flow than other animals, and the lack of eye pigment in albinos make the effects easier to visualize. The numbers of rabbits used for this purpose has fallen substantially over the past two decades. In 1996, there were 3,693 procedures on rabbits for eye irritation in the UK,<ref>Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain, 1996 – UK Home Office, Table 13</ref> and in 2017 this number was just 63.<ref name=UK2017 /> Rabbits are also frequently used for the production of polyclonal antibodies. | |||