| Revision as of 11:23, 18 October 2010 editRich Farmbrough (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors1,725,617 editsm Reverted edits by CBM (talk) to last version by SmackBot← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:38, 1 December 2024 edit undoTule-hog (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,650 edits →Works cited: correct author-link | ||

| (387 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|In mathematics, a statement that has been proven}} | |||

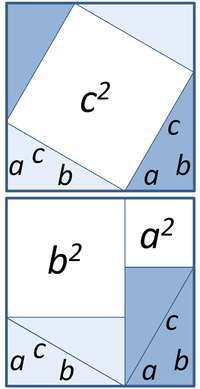

| ] has at least 370 known proofs<ref name='Loomis'>For full text of 2nd edition of 1940, see {{cite web|url=http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED037335.pdf|author=Elisha Scott Loomis |title=The Pythagorean proposition: its demonstrations analyzed and classified, and bibliography of sources for data of the four kinds of proofs |accessdate=2010-09-26 |work=] |publisher=] (IES) of the ] }} Originally published in 1940 and reprinted in 1968 by National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.</ref>]] | |||

| {{distinguish|Teorema (disambiguation){{!}}Teorema|Theorema (disambiguation){{!}}Theorema|Theory (disambiguation){{!}}Theory}} | |||

| In ], a '''theorem''' is a ] which has been ] on the basis of previously established statements, such as other theorems, and previously accepted statements, such as ]s. The derivation of a theorem is often interpreted as a proof of the truth of the resulting expression, but different ]s can yield other interpretations, depending on the meanings of the derivation rules. Theorems have two components, called the ] and the conclusions. The proof of a mathematical theorem is a logical argument demonstrating that the conclusions are a necessary consequence of the hypotheses, in the sense that if the hypotheses are true then the conclusions must also be true, without any further assumptions. The concept of a theorem is therefore fundamentally '']'', in contrast to the notion of a scientific ], which is '']''.<ref>However, both theorems and theories are investigations. See {{harvnb|Heath|1897}} Introduction, The terminology of ], p. clxxxii:"theorem (θεὼρνμα) from θεωρεἳν to investigate"</ref> | |||

| ] has at least 370 known proofs.<ref name='Loomis'>{{cite web|url=http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED037335.pdf|author=Elisha Scott Loomis |title=The Pythagorean proposition: its demonstrations analyzed and classified, and bibliography of sources for data of the four kinds of proofs |access-date=2010-09-26 |work=] |publisher=] (IES) of the ] }} Originally published in 1940 and reprinted in 1968 by National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.</ref>]] | |||

| In ] and ], a '''theorem''' is a ] that has been ], or can be proven.{{efn|In general, the distinction is weak, as the standard way to prove that a statement is provable consists of proving it. However, in mathematical logic, one considers often the set of all theorems of a theory, although one cannot prove them individually.}}<ref>{{Cite Merriam-Webster|Theorem|access-date=1 December 2024}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/theorem|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191102041621/https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/theorem|url-status=dead|archive-date=November 2, 2019|title=Theorem {{!}} Definition of Theorem by Lexico|website=Lexico Dictionaries {{!}} English|language=en|access-date=2019-11-02}}</ref> The ''proof'' of a theorem is a ] that uses the inference rules of a ] to establish that the theorem is a ] of the ]s and previously proved theorems. | |||

| Although they can be written in a completely symbolic form using, for example, ], theorems are often expressed in a natural language such as English. The same is true of proofs, which are often expressed as logically organized and clearly worded informal arguments intended to demonstrate that a formal symbolic proof can be constructed. Such arguments are typically easier to check than purely symbolic ones — indeed, many mathematicians would express a preference for a proof that not only demonstrates the validity of a theorem, but also explains in some way ''why'' it is obviously true. In some cases, a picture alone may be sufficient to prove a theorem. Because theorems lie at the core of mathematics, they are also central to its aesthetics. Theorems are often described as being "trivial", or "difficult", or "deep", or even "beautiful". These subjective judgments vary not only from person to person, but also with time: for example, as a proof is simplified or better understood, a theorem that was once difficult may become trivial. On the other hand, a deep theorem may be simply stated, but its proof may involve surprising and subtle connections between disparate areas of mathematics. ] is a particularly well-known example of such a theorem. | |||

| In mainstream mathematics, the axioms and the inference rules are commonly left implicit, and, in this case, they are almost always those of ] with the ] (ZFC), or of a less powerful theory, such as ].{{efn|An exception is the original ], which relies implicitly on ]s, whose existence requires the addition of a new axiom to set theory.<ref>{{cite journal| | |||

| == Informal accounts of theorems == | |||

| title=What does it take to prove Fermat's last theorem? Grothendieck and the logic of number theory| | |||

| first=Colin|last= McLarty| | |||

| journal=The Review of Symbolic Logic| | |||

| volume=13| | |||

| number=3| | |||

| pages=359–377| | |||

| year=2010| | |||

| publisher=Cambridge University Press| | |||

| doi=10.2178/bsl/1286284558| | |||

| s2cid=13475845}} </ref> This reliance on a new axiom of set theory has since been removed.<ref> {{cite journal| | |||

| title=The large structures of Grothendieck founded on finite order arithmetic| | |||

| first=Colin|last= McLarty| | |||

| journal=Bulletin of Symbolic Logic| | |||

| volume=16| | |||

| number=2| | |||

| pages=296–325| | |||

| year=2020| | |||

| publisher=Cambridge University Press| | |||

| doi=10.1017/S1755020319000340| | |||

| arxiv=1102.1773| | |||

| s2cid=118395028}}</ref> Nevertheless, it is rather astonishing that the first proof of a statement expressed in elementary ] involves the existence of very large infinite sets.}} Generally, an assertion that is explicitly called a theorem is a proved result that is not an immediate consequence of other known theorems. Moreover, many authors qualify as ''theorems'' only the most important results, and use the terms ''lemma'', ''proposition'' and ''corollary'' for less important theorems. | |||

| In ], the concepts of theorems and proofs have been ] in order to allow mathematical reasoning about them. In this context, statements become ]s of some ]. A ] consists of some basis statements called ''axioms'', and some ''deducing rules'' (sometimes included in the axioms). The theorems of the theory are the statements that can be derived from the axioms by using the deducing rules.{{efn|A theory is often identified with the set of its theorems. This is avoided here for clarity, and also for not depending on ].}} This formalization led to ], which allows proving general theorems about theorems and proofs. In particular, ] show that every ] theory containing the natural numbers has true statements on natural numbers that are not theorems of the theory (that is they cannot be proved inside the theory). | |||

| ], many theorems are of the form of an ]: ''if A, then B''. Such a theorem does not state that ''B'' is always true, only that ''B'' must be true if ''A'' is true. In this case ''A'' is called the ''']''' of the theorem (note that "hypothesis" here is something very different from a ]) and ''B'' the '''conclusion''' (''A'' and ''B'' can also be denoted the ''antecedent'' and ''consequent''). The theorem "If ''n'' is an even ] then ''n''/2 is a natural number" is a typical example in which the hypothesis is that "''n'' is an even natural number" and the conclusion is that "''n''/2 is also a natural number". | |||

| As the axioms are often abstractions of properties of the ], theorems may be considered as expressing some truth, but in contrast to the notion of a ], which is '']'', the justification of the truth of a theorem is purely ].<ref name=":0">{{Citation|last=Markie|first=Peter|title=Rationalism vs. Empiricism|date=2017|url=https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/rationalism-empiricism/|encyclopedia=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy|editor-last=Zalta|editor-first=Edward N.|edition=Fall 2017|publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University|access-date=2019-11-02}}</ref>{{efn|However, both theorems and scientific law are the result of investigations. See {{harvnb|Heath|1897|p=clxxxii |loc=Introduction, The terminology of ]}}: "theorem (θεὼρνμα) from θεωρεἳν to investigate"}} | |||

| In order to be proven, a theorem must be expressible as a precise, formal statement. Nevertheless, theorems are usually expressed in natural language rather than in a completely symbolic form, with the intention that the reader will be able to produce a formal statement from the informal one. In addition, there are often hypotheses which are understood in context, rather than explicitly stated, though a stated hypothesis must coincide with the overall intuition of the theorem for it to be accepted as a solution under Newtons terms. | |||

| A '']'' is a tentative proposition that may evolve to become a theorem if proven true. | |||

| ==Theoremhood and truth== | |||

| It is common in mathematics to choose a number of hypotheses that are assumed to be true within a given theory, and then declare that the theory consists of all theorems provable using those hypotheses as assumptions. In this case the hypotheses that form the foundational basis are called the axioms (or postulates) of the theory. The field of mathematics known as ] studies formal axiom systems and the proofs that can be performed within them. | |||

| Until the end of the 19th century and the ], all mathematical theories were built from a few basic properties that were considered as self-evident; for example, the facts that every ] has a successor, and that there is exactly one ] that passes through two given distinct points. These basic properties that were considered as absolutely evident were called ]s or ]; for example ]. All theorems were proved by using implicitly or explicitly these basic properties, and, because of the evidence of these basic properties, a proved theorem was considered as a definitive truth, unless there was an error in the proof. For example, the sum of the ]s of a ] equals 180°, and this was considered as an undoubtable fact. | |||

| One aspect of the foundational crisis of mathematics was the discovery of ] that do not lead to any contradiction, although, in such geometries, the sum of the angles of a triangle is different from 180°. So, the property ''"the sum of the angles of a triangle equals 180°"'' is either true or false, depending whether Euclid's fifth postulate is assumed or denied. Similarly, the use of "evident" basic properties of ] leads to the contradiction of ]. This has been resolved by elaborating the rules that are allowed for manipulating sets. | |||

| ] map with five colors such that no two regions with the same color meet. It can actually be colored in this way with only four colors. The ] states that such colorings are possible for any planar map, but every known proof involves a computational search that is too long to check by hand.]] | |||

| Some theorems are "trivial," in the sense that they follow from definitions, axioms, and other theorems in obvious ways and do not contain any surprising insights. Some, on the other hand, may be called "deep": their proofs may be long and difficult, involve areas of mathematics superficially distinct from the statement of the theorem itself, or show surprising connections between disparate areas of mathematics.<ref>{{MathWorld|title=Deep Theorem|urlname=DeepTheorem}}</ref> A theorem might be simple to state and yet be deep. An excellent example is Fermat's Last Theorem, and there are many other examples of simple yet deep theorems in ] and ], among other areas. | |||

| This crisis has been resolved by revisiting the foundations of mathematics to make them more ]. In these new foundations, a theorem is a ] of a ] that can be proved from the ]s and ] of the theory. So, the above theorem on the sum of the angles of a triangle becomes: ''Under the axioms and inference rules of ], the sum of the interior angles of a triangle equals 180°''. Similarly, Russell's paradox disappears because, in an axiomatized set theory, the ''set of all sets'' cannot be expressed with a well-formed formula. More precisely, if the set of all sets can be expressed with a well-formed formula, this implies that the theory is ], and every well-formed assertion, as well as its negation, is a theorem. | |||

| There are other theorems for which a proof is known, but the proof cannot easily be written down. The most prominent examples are the four color theorem and the ]. Both of these theorems are only known to be true by reducing them to a computational search which is then verified by a computer program. Initially, many mathematicians did not accept this form of proof, but it has become more widely accepted in recent years. The mathematician ] has even gone so far as to claim that these are possibly the only nontrivial results that mathematicians have ever proved.<ref>{{Cite web|author=Doron Zeilberger|authorlink=Doron Zeilberger|title=Opinion 51|url=http://www.math.rutgers.edu/~zeilberg/Opinion51.html}}</ref> Many mathematical theorems can be reduced to more straightforward computation, including polynomial identities, trigonometric identities and hypergeometric identities.<ref>Petkovsek et al. 1996.</ref>{{page number}} | |||

| In this context, the validity of a theorem depends only on the correctness of its proof. It is independent from the truth, or even the significance of the axioms. This does not mean that the significance of the axioms is uninteresting, but only that the validity of a theorem is independent from the significance of the axioms. This independence may be useful by allowing the use of results of some area of mathematics in apparently unrelated areas. | |||

| ==Relation to proof== | |||

| An important consequence of this way of thinking about mathematics is that it allows defining mathematical theories and theorems as ]s, and to prove theorems about them. Examples are ]. In particular, there are well-formed assertions than can be proved to not be a theorem of the ambient theory, although they can be proved in a wider theory. An example is ], which can be stated in ], but is proved to be not provable in Peano arithmetic. However, it is provable in some more general theories, such as ]. | |||

| The notion of a theorem is deeply intertwined with the concept of proof. Indeed, theorems are true precisely in the sense that they possess proofs. Therefore, to establish a mathematical statement as a theorem, the existence of a line of reasoning from axioms in the system (and other, already established theorems) to the given statement must be demonstrated. | |||

| ==Epistemological considerations== | |||

| Although the proof is necessary to produce a theorem, it is not usually considered part of the theorem. And even though more than one proof may be known for a single theorem, only one proof is required to establish the theorem's validity. The Pythagorean theorem and the law of quadratic reciprocity are contenders for the title of theorem with the greatest number of distinct proofs. | |||

| Many mathematical theorems are conditional statements, whose proofs deduce conclusions from conditions known as '''hypotheses''' or ]s. In light of the interpretation of proof as justification of truth, the conclusion is often viewed as a ] of the hypotheses. Namely, that the conclusion is true in case the hypotheses are true—without any further assumptions. However, the conditional could also be interpreted differently in certain ]s, depending on the meanings assigned to the derivation rules and the conditional symbol (e.g., ]). | |||

| Although theorems can be written in a completely symbolic form (e.g., as propositions in ]), they are often expressed informally in a natural language such as English for better readability. The same is true of proofs, which are often expressed as logically organized and clearly worded informal arguments, intended to convince readers of the truth of the statement of the theorem beyond any doubt, and from which a formal symbolic proof can in principle be constructed. | |||

| ==Theorems in logic== | |||

| {{refimprove|section}} | |||

| {{pov-section|Formalism}} | |||

| ], especially in the field of proof theory, considers theorems as statements (called ''']s''' or ''']s''') of a formal language. The statements of the language are strings of symbols and may be broadly divided into ] and well-formed formulas. A set of '''deduction rules''', also called '''transformation rules''' or ], must be provided. These deduction rules tell exactly when a formula can be derived from a set of premises. The set of well-formed formulas may be broadly divided into theorems and non-theorems. However, according to ], a formal system will often simply define all of its well-formed formula as theorems.<ref>Hofstadter 1980</ref>{{page number|Also need to know the edition, and verify that in the references. There are at least 4 English language editions of the book, in 1979, 1980, and two in 1999.}} | |||

| In addition to the better readability, informal arguments are typically easier to check than purely symbolic ones—indeed, many mathematicians would express a preference for a proof that not only demonstrates the validity of a theorem, but also explains in some way ''why'' it is obviously true. In some cases, one might even be able to substantiate a theorem by using a picture as its proof. | |||

| Different sets of derivation rules give rise to different interpretations of what it means for an expression to be a theorem. Some derivation rules and formal languages are intended to capture mathematical reasoning; the most common examples use ]. Other deductive systems describe ], such as the reduction rules for ]. | |||

| Because theorems lie at the core of mathematics, they are also central to its ]. Theorems are often described as being "trivial", or "difficult", or "deep", or even "beautiful". These subjective judgments vary not only from person to person, but also with time and culture: for example, as a proof is obtained, simplified or better understood, a theorem that was once difficult may become trivial.<ref>{{mathworld|id=Theorem|title=Theorem}}</ref> On the other hand, a deep theorem may be stated simply, but its proof may involve surprising and subtle connections between disparate areas of mathematics. ] is a particularly well-known example of such a theorem.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=http://www.math.mcgill.ca/darmon/pub/Articles/Expository/05.DDT/paper.pdf|title=Fermat's Last Theorem|last1=Darmon|first1=Henri|last2=Diamond|first2=Fred|date=2007-09-09|website=McGill University – Department of Mathematics and Statistics|access-date=2019-11-01|last3=Taylor|first3=Richard}}</ref> | |||

| The definition of theorems as elements of a formal language allows for results in proof theory that study the structure of formal proofs and the structure of provable formulas. The most famous result is Gödel's incompleteness theorem; by representing theorems about basic number theory as expressions in a formal language, and then representing this language within number theory itself, Gödel constructed examples of statements that are neither provable nor disprovable from axiomatizations of number theory. | |||

| {{-}}<!-- stop picture bleeding into completely unrelated next section --> | |||

| == Informal account of theorems == | |||

| ==Relation with scientific theories== | |||

| ], many theorems are of the form of an ]: ''If A, then B''. Such a theorem does not assert ''B'' — only that ''B'' is a necessary consequence of ''A''. {{anchor|Hypothesis|Conclusion|Proposition}}In this case, ''A'' is called the ''hypothesis'' of the theorem ("hypothesis" here means something very different from a ]), and ''B'' the ''conclusion'' of the theorem. The two together (without the proof) are called the ''proposition'' or ''statement'' of the theorem (e.g. "''If A, then B''" is the ''proposition''). Alternatively, ''A'' and ''B'' can be also termed the '']'' and the '']'', respectively.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://intrologic.stanford.edu/glossary/implication.html |title=Implication |website=intrologic.stanford.edu |access-date=2019-11-02}}</ref> The theorem "If ''n'' is an even ], then ''n''/2 is a natural number" is a typical example in which the hypothesis is "''n'' is an even natural number", and the conclusion is "''n''/2 is also a natural number". | |||

| Theorems in mathematics and theories in science are fundamentally different in their ]. A scientific theory cannot be proven; its key attribute is that it is ], that is, it makes predictions about the natural world that are testable by ]s. Any disagreement between prediction and experiment demonstrates the incorrectness of the scientific theory, or at least limits its accuracy or domain of validity. Mathematical theorems, on the other hand, are purely abstract formal statements: the proof of a theorem cannot involve experiments or other empirical evidence in the same way such evidence is used to support scientific theories. | |||

| In order for a theorem to be proved, it must be in principle expressible as a precise, formal statement. However, theorems are usually expressed in natural language rather than in a completely symbolic form—with the presumption that a formal statement can be derived from the informal one. | |||

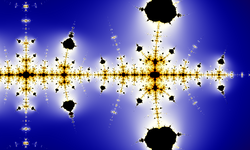

| ]: one way to illustrate its complexity is to extend the iteration from the natural numbers to the complex numbers. The result is a fractal, which (in accordance with ]) resembles the ].]] | |||

| Nonetheless, there is some degree of empiricism and data collection involved in the discovery of mathematical theorems. By establishing a pattern, sometimes with the use of a powerful computer, mathematicians may have an idea of what to prove, and in some cases even a plan for how to set about doing the proof. For example, the Collatz conjecture has been verified for start values up to about 2.88 × 10<sup>18</sup>. The ] has been verified for the first 10 trillion zeroes of the ]. Neither of these statements is considered to be proven. | |||

| It is common in mathematics to choose a number of hypotheses within a given language and declare that the theory consists of all statements provable from these hypotheses. These hypotheses form the foundational basis of the theory and are called ]s or postulates. The field of mathematics known as ] studies formal languages, axioms and the structure of proofs. | |||

| Such evidence does not constitute proof. For example, the ] is a statement about natural numbers that is now known to be false, but no explicit counterexample (i.e., a natural number ''n'' for which the Mertens function ''M''(''n'') equals or exceeds the square root of ''n'') is known: all numbers less than 10<sup>14</sup> have the Mertens property, and the smallest number which does not have this property is only known to be less than the ] of 1.59 × 10<sup>40</sup>, which is approximately 10 to the power 4.3 × 10<sup>39</sup>. Since the number of particles in the universe is generally considered to be less than 10 to the power 100 (a ]), there is no hope to find an explicit counterexample by ]. | |||

| ] map with five colors such that no two regions with the same color meet. It can actually be colored in this way with only four colors. The ] states that such colorings are possible for any planar map, but every known proof involves a computational search that is too long to check by hand.]] | |||

| Note that the word "theory" also exists in mathematics, to denote a body of mathematical axioms, definitions and theorems, as in, for example, ]. There are also "theorems" in science, particularly physics, and in engineering, but they often have statements and proofs in which physical assumptions and intuition play an important role; the physical axioms on which such "theorems" are based are themselves falsifiable. | |||

| Some theorems are "]", in the sense that they follow from definitions, axioms, and other theorems in obvious ways and do not contain any surprising insights. Some, on the other hand, may be called "deep", because their proofs may be long and difficult, involve areas of mathematics superficially distinct from the statement of the theorem itself, or show surprising connections between disparate areas of mathematics.<ref>{{MathWorld|title=Deep Theorem|urlname=DeepTheorem}}</ref> A theorem might be simple to state and yet be deep. An excellent example is ],<ref name=":1" /> and there are many other examples of simple yet deep theorems in ] and ], among other areas. | |||

| Other theorems have a known proof that cannot easily be written down. The most prominent examples are the four color theorem and the ]. Both of these theorems are only known to be true by reducing them to a computational search that is then verified by a computer program. Initially, many mathematicians did not accept this form of proof, but it has become more widely accepted. The mathematician ] has even gone so far as to claim that these are possibly the only nontrivial results that mathematicians have ever proved.<ref>{{cite web|author=Doron Zeilberger|author-link=Doron Zeilberger|title=Opinion 51|url=http://www.math.rutgers.edu/~zeilberg/Opinion51.html}}</ref> Many mathematical theorems can be reduced to more straightforward computation, including polynomial identities, trigonometric identities{{efn|Such as the derivation of the formula for <math>\tan (\alpha + \beta)</math> from the ].}} and hypergeometric identities.{{sfn|Petkovsek|Wilf|Zeilberger|1996}}{{Page needed|date=October 2010}} | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| Theorems are often indicated by several other terms: the actual label "theorem" is reserved for the most important results, whereas results which are less important, or distinguished in other ways, are named by different terminology. | |||

| ==Relation with scientific theories== | |||

| * A ''''']''''' is a statement not associated with any particular theorem. This term sometimes connotes a statement with a simple proof, or a basic consequence of a definition that needs to be stated, but is obvious enough to require no proof. The word ''proposition'' is sometimes used for the statement part of a ''theorem''. | |||

| * A ''''']''''' is a "pre-theorem", a statement that forms part of the proof of a larger theorem. The distinction between theorems and lemmas is rather arbitrary, since one ] major result is another's minor claim. ] and ], for example, are interesting enough that some authors present the nominal lemma without going on to use it in the proof of a theorem. | |||

| * A ''''']''''' is a proposition that follows with little or no proof from one other theorem or definition. That is, proposition ''B'' is a corollary of a proposition ''A'' if ''B'' can readily be deduced from ''A''. | |||

| * A '''''claim''''' is a necessary or independently interesting result that may be part of the proof of another statement. Despite the name, claims must be proved{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}}. | |||

| Theorems in mathematics and theories in science are fundamentally different in their ]. A scientific theory cannot be proved; its key attribute is that it is ], that is, it makes predictions about the natural world that are testable by ]s. Any disagreement between prediction and experiment demonstrates the incorrectness of the scientific theory, or at least limits its accuracy or domain of validity. Mathematical theorems, on the other hand, are purely abstract formal statements: the proof of a theorem cannot involve experiments or other empirical evidence in the same way such evidence is used to support scientific theories.<ref name=":0"/> | |||

| There are other terms, less commonly used, which are conventionally attached to proven statements, so that certain theorems are referred to by historical or customary names. For examples: | |||

| ]: one way to illustrate its complexity is to extend the iteration from the natural numbers to the complex numbers. The result is a ], which (in accordance with ]) resembles the ].]] | |||

| Nonetheless, there is some degree of empiricism and data collection involved in the discovery of mathematical theorems. By establishing a pattern, sometimes with the use of a powerful computer, mathematicians may have an idea of what to prove, and in some cases even a plan for how to set about doing the proof. It is also possible to find a single counter-example and so establish the impossibility of a proof for the proposition as-stated, and possibly suggest restricted forms of the original proposition that might have feasible proofs. | |||

| For example, both the ] and the ] are well-known unsolved problems; they have been extensively studied through empirical checks, but remain unproven. The ] has been verified for start values up to about 2.88 × 10<sup>18</sup>. The ] has been verified to hold for the first 10 trillion non-trivial zeroes of the ]. Although most mathematicians can tolerate supposing that the conjecture and the hypothesis are true, neither of these propositions is considered proved. | |||

| Such evidence does not constitute proof. For example, the ] is a statement about natural numbers that is now known to be false, but no explicit counterexample (i.e., a natural number ''n'' for which the Mertens function ''M''(''n'') equals or exceeds the square root of ''n'') is known: all numbers less than 10<sup>14</sup> have the Mertens property, and the smallest number that does not have this property is only known to be less than the ] of 1.59 × 10<sup>40</sup>, which is approximately 10 to the power 4.3 × 10<sup>39</sup>. Since the number of particles in the universe is generally considered less than 10 to the power 100 (a ]), there is no hope to find an explicit counterexample by ]. | |||

| The word "theory" also exists in mathematics, to denote a body of mathematical axioms, definitions and theorems, as in, for example, ] (see ]). There are also "theorems" in science, particularly physics, and in engineering, but they often have statements and proofs in which physical assumptions and intuition play an important role; the physical axioms on which such "theorems" are based are themselves falsifiable. | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| A number of different terms for mathematical statements exist; these terms indicate the role statements play in a particular subject. The distinction between different terms is sometimes rather arbitrary, and the usage of some terms has evolved over time. | |||

| * An '']'' or ''postulate'' is a fundamental assumption regarding the object of study, that is accepted without proof. A related concept is that of a '']'', which gives the meaning of a word or a phrase in terms of known concepts. Classical geometry discerns between axioms, which are general statements; and postulates, which are statements about geometrical objects.{{sfn|Wentworth|Smith|1913|loc=}} Historically, axioms were regarded as "]"; today they are merely ''assumed'' to be true. | |||

| * A '']'' is an unproved statement that is believed to be true. Conjectures are usually made in public, and named after their maker (for example, ] and ]). The term ''hypothesis'' is also used in this sense (for example, ]), which should not be confused with "hypothesis" as the premise of a proof. Other terms are also used on occasion, for example ''problem'' when people are not sure whether the statement should be believed to be true. ] was historically called a theorem, although, for centuries, it was only a conjecture. | |||

| <!-- The following definition repeats the lead for easy reference --> | |||

| * A ''theorem'' is a statement that has been proven to be true based on axioms and other theorems. | |||

| * A '']'' is a theorem of lesser importance, or one that is considered so elementary or immediately obvious, that it may be stated without proof. This should not be confused with "proposition" as used in ]. In classical geometry the term "proposition" was used differently: in ]'s ] ({{circa|300 BCE}}), all theorems and geometric constructions were called "propositions" regardless of their importance. | |||

| * A '']'' is an "accessory proposition" - a proposition with little applicability outside its use in a particular proof. Over time a lemma may gain in importance and be considered a ''theorem'', though the term "lemma" is usually kept as part of its name (e.g. ], ], and ]). | |||

| * A '']'' is a proposition that follows immediately from another theorem or axiom, with little or no required proof.{{sfn|Wentworth|Smith|1913|loc=}} A corollary may also be a restatement of a theorem in a simpler form, or for a ]: for example, the theorem "all internal angles in a ] are ]s" has a corollary that "all internal angles in a '']'' are ]s" - a square being a special case of a rectangle. | |||

| * A '']'' of a theorem is a theorem with a similar statement but a broader scope, from which the original theorem can be deduced as a ] (a ''corollary''). {{efn|Often, when the less general or "corollary"-like theorem is proven first, it is because the proof of the more general form requires the simpler, corollary-like form, for use as a what is functionally a lemma, or "helper" theorem.}} | |||

| Other terms may also be used for historical or customary reasons, for example: | |||

| * ''''']''''', used for theorems which state an equality between two mathematical expressions. Examples include ] and ]. | |||

| * '''''Rule''''', used for certain theorems such as ] and ], that establish useful formulas. | |||

| * ''''']'''''. Examples include the ], the ], and ].<ref>The word ''law'' can also refer to an axiom, a ], or, in ], a ].</ref> | |||

| * ''''']'''''. Examples include ], the ], and the ]. | |||

| * A ''''']''''' is a reverse theorem. For example, If a theorem states that A is related to B, its converse would state that B is related to A. The converse of a theorem need not be always true. | |||

| * An '']'' is a theorem stating an equality between two expressions, that holds for any value within its ] (e.g. ] and ]). | |||

| A few well-known theorems have even more idiosyncratic names. The ''']''' is a theorem expressing the outcome of division in the natural numbers and more general rings. The ''']''' is a theorem in ] that is ]ical in the sense that it contradicts common intuitions about volume in three-dimensional space. | |||

| * A ''rule'' is a theorem that establishes a useful formula (e.g. ] and ]). | |||

| * A '']'' or '']'' is a theorem with wide applicability (e.g. the ], ], ], ], the ], and the ]).{{efn|The word ''law'' can also refer to an axiom, a ], or, in ], a ].}} | |||

| A few well-known theorems have even more idiosyncratic names, for example, the ], ], and the ]. | |||

| An unproven statement that is believed to be true is called a '''''conjecture''''' (or sometimes a '''hypothesis''', but with a different meaning from the one discussed above). To be considered a conjecture, a statement must usually be proposed publicly, at which point the name of the proponent may be attached to the conjecture, as with ]. Other famous conjectures include the Collatz conjecture and the Riemann hypothesis. | |||

| ==Layout== | ==Layout== | ||

| Line 68: | Line 102: | ||

| A theorem and its proof are typically laid out as follows: | A theorem and its proof are typically laid out as follows: | ||

| : |

:''Theorem'' (name of the person who proved it, along with year of discovery or publication of the proof) | ||

| :''Statement of theorem (sometimes called the ''proposition'') |

:''Statement of theorem (sometimes called the ''proposition'')'' | ||

| : |

:''Proof'' | ||

| :''Description of proof |

:''Description of proof'' | ||

| :''End |

:''End'' | ||

| The end of the proof may be |

The end of the proof may be signaled by the letters ] (''quod erat demonstrandum'') or by one of the ] marks, such as "□" or "∎", meaning "end of proof", introduced by ] following their use in magazines to mark the end of an article.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://jeff560.tripod.com/set.html |title=Earliest Uses of Symbols of Set Theory and Logic |website=jeff560.tripod.com |access-date=2019-11-02 |df=dmy-all}}</ref> | ||

| The exact style |

The exact style depends on the author or publication. Many publications provide instructions or ] for typesetting in the ]. | ||

| It is common for a theorem to be preceded by ]s describing the exact meaning of the terms used in the theorem. It is also common for a theorem to be preceded by a number of propositions or lemmas which are then used in the proof. However, lemmas are sometimes embedded in the proof of a theorem, either with nested proofs, or with their proofs presented after the proof of the theorem. | It is common for a theorem to be preceded by ]s describing the exact meaning of the terms used in the theorem. It is also common for a theorem to be preceded by a number of propositions or lemmas which are then used in the proof. However, lemmas are sometimes embedded in the proof of a theorem, either with nested proofs, or with their proofs presented after the proof of the theorem. | ||

| Corollaries to a theorem are either presented between the theorem and the proof, or directly after the proof. Sometimes corollaries have proofs of their own |

Corollaries to a theorem are either presented between the theorem and the proof, or directly after the proof. Sometimes, corollaries have proofs of their own that explain why they follow from the theorem. | ||

| ==Lore== | ==Lore== | ||

| It has been estimated that over a quarter of a million theorems are proved every year. |

It has been estimated that over a quarter of a million theorems are proved every year.{{sfn|Hoffman|1998|p=204}} | ||

| The well-known ], ], is probably due to ], although it is often attributed to Rényi's colleague ] (and Rényi may have been thinking of Erdős), who was famous for the many theorems he produced, the ] of his collaborations, and his coffee drinking. |

The well-known ], ], is probably due to ], although it is often attributed to Rényi's colleague ] (and Rényi may have been thinking of Erdős), who was famous for the many theorems he produced, the ] of his collaborations, and his coffee drinking.{{sfn|Hoffman|1998| p= 7}} | ||

| The ] is regarded by some to be the longest proof of a theorem |

The ] is regarded by some to be the longest proof of a theorem. It comprises tens of thousands of pages in 500 journal articles by some 100 authors. These papers are together believed to give a complete proof, and several ongoing projects hope to shorten and simplify this proof.<ref>, Richard Elwes, Plus Magazine, Issue 41 December 2006.</ref> Another theorem of this type is the ] whose computer generated proof is too long for a human to read. It is among the longest known proofs of a theorem whose statement can be easily understood by a layman.{{citation needed|date=April 2020}} | ||

| ==Theorems in logic== | |||

| == Formalized account of theorems == | |||

| A theorem may be expressed in a ] (or "formalized"). A formal theorem is the purely formal analogue of a theorem. In general, a formal theorem is a type of ] that satisfies certain logical and syntactic conditions. The notation {{tee}} <math>S</math> is often used to indicate that <math>S</math> is a theorem. | |||

| In ], a ] is a set of sentences within a ]. A sentence is a ] with no free variables. A sentence that is a member of a theory is one of its theorems, and the theory is the set of its theorems. Usually a theory is understood to be closed under the relation of ]. Some accounts define a theory to be closed under the ] relation (<math>\models</math>), while others define it to be closed under the ], or derivability relation (<math>\vdash</math>).{{sfn|Boolos|Burgess|Jeffrey|2007|p=191}}{{sfn|Chiswell|Hodges|p=172}}{{sfn|Enderton|2001|p=148}}{{sfn|Hedman|2004|p=89}}{{sfn|Hinman|2005|p=139}}{{sfn|Hodges|1993|p=33}}{{sfn|Johnstone|1987|p=21}}{{sfn|Monk|1976|p=208}}{{sfn|Rautenberg|2010|p=81}}{{sfn|van Dalen|1994|p=104}} | |||

| Formal theorems consist of ] of a ] and the ]s of a formal system. Specifically, a formal theorem is always the last formula of a ] in some formal system each formula of which is a ] of the formulas which came before it in the derivation. The initially accepted formulas in the derivation are called its '''axioms''', and are the basis on which the theorem is derived. A ] of theorems is called a '''theory'''. | |||

| {{Clear}}<!-- stop picture bleeding into completely unrelated next section --> | |||

| What makes formal theorems useful and of interest is that they can be ] as true ]s and their derivations may be interpreted as a proof of the ] of the resulting expression. A set of formal theorems may be referred to as a ''']'''. A theorem whose interpretation is a true statement about a formal system is called a ''']'''. | |||

| ] that can be constructed from ]s. The ] and ] may be broadly divided into ] and ]s. A formal language can be thought of as identical to the set of its well-formed formulas. The set of well-formed formulas may be broadly divided into theorems and non-theorems.]] | |||

| === Syntax and semantics === | |||

| {{Main|Syntax (logic)|Formal semantics}} | |||

| For a theory to be closed under a derivability relation, it must be associated with a ] that specifies how the theorems are derived. The deductive system may be stated explicitly, or it may be clear from the context. The closure of the empty set under the relation of logical consequence yields the set that contains just those sentences that are the theorems of the deductive system. | |||

| The concept of a formal theorem is fundamentally syntactic, in contrast to the notion of a "true proposition" in which ] are introduced. Different deductive systems may be constructed so as to yield other interpretations, depending on the presumptions of the derivation rules (i.e. ], ] or other ]). The ] of a formal system depends on whether or not all of its theorems are also ]. A validity is a formula that is true under any possible interpretation, e.g. in classical propositional logic validities are ]. A formal system is considered ] when all of its tautologies are also theorems. | |||

| In the broad sense in which the term is used within logic, a theorem does not have to be true, since the theory that contains it may be ] relative to a given semantics, or relative to the standard ] of the underlying language. A theory that is ] has all sentences as theorems. | |||

| === Derivation of a theorem === | |||

| {{Main|Formal proof}} | |||

| The definition of theorems as sentences of a formal language is useful within ], which is a branch of mathematics that studies the structure of formal proofs and the structure of provable formulas. It is also important in ], which is concerned with the relationship between formal theories and structures that are able to provide a semantics for them through ]. | |||

| The notion of a theorem is very closely connected to its formal proof (also called a "derivation"). To illustrate how derivations are done, we will work in a very simplified formal system. Let us call ours <math>\mathcal{FS}</math> Its alphabet consists only of two symbols { '''A''', '''B''' } and its formation rule for formulas is: | |||

| :Any string of symbols of <math>\mathcal{FS}</math> which is at least 3 symbols long, and which is not infinitely long, is a formula. Nothing else is a formula. | |||

| Although theorems may be uninterpreted sentences, in practice mathematicians are more interested in the meanings of the sentences, i.e. in the propositions they express. What makes formal theorems useful and interesting is that they may be interpreted as true propositions and their derivations may be interpreted as a proof of their truth. A theorem whose interpretation is a true statement ''about'' a formal system (as opposed to ''within'' a formal system) is called a '']''. | |||

| The single axiom of <math>\mathcal{FS}</math> is: | |||

| :'''ABBA''' | |||

| Some important theorems in mathematical logic are: | |||

| The only ] (transformation rule) for <math>\mathcal{FS}</math> is: | |||

| :Any occurrence of "'''A'''" in a theorem may be replaced by an occurrence of the string "'''AB'''" and the result is a theorem. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| === Syntax and semantics === | |||

| Theorems in <math>\mathcal{FS}</math> are defined as those formulae which have a derivation ending with that formula. For example | |||

| {{Main|Syntax (logic)|Formal semantics (logic)}} | |||

| #'''ABBA''' (Given as axiom) | |||

| #'''ABBBA''' (by applying the transformation rule) | |||

| #'''ABBBAB''' (by applying the transformation rule) | |||

| is a derivation. Therefore "'''ABBBAB'''" is a theorem of <math>\mathcal{FS} \,.</math> The notion of truth (or falsity) cannot be applied to the formula "'''ABBBAB'''" until an interpretation is given to its symbols. Thus in this example, the formula does not yet represent a proposition, but is merely an empty abstraction. | |||

| The concept of a formal theorem is fundamentally syntactic, in contrast to the notion of a ''true proposition,'' which introduces ]. Different deductive systems can yield other interpretations, depending on the presumptions of the derivation rules (i.e. ], ] or other ]). The ] of a formal system depends on whether or not all of its theorems are also ]. A validity is a formula that is true under any possible interpretation (for example, in classical propositional logic, validities are ]). A formal system is considered ] when all of its theorems are also tautologies. | |||

| Two metatheorems of <math>\mathcal{FS}</math> are: | |||

| :Every theorem begins with "'''A'''". | |||

| :Every theorem has exactly two "'''A'''"s. | |||

| === Interpretation of a formal theorem === | === Interpretation of a formal theorem === | ||

| {{Main|Interpretation (logic)}} | {{Main|Interpretation (logic)}}<!-- Wouldn't this fit better in the page "formal theorem"? --> | ||

| === Theorems and theories === | === Theorems and theories === | ||

| Line 133: | Line 166: | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal| |

{{Portal|Philosophy|Mathematics}} | ||

| * |

*] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| == |

==Citations== | ||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| <references/> | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | ===References=== | ||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|authorlink=Archimedes|title=The works of Archimedes|last=Heath|first=Sir Thomas Little|publisher=Dover|year=1897|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=FIY5AAAAMAAJ&dq=works+of+archimedes&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=PRfqkNAFl-&sig=vRhyLwEr-wNV-bGsOB9eKas-63E&hl=en&ei=Smn_SuL6FZPElAfmj7SSCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CBAQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=theorem&f=false|accessdate=2009-11-15}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|title = ]: The Story of Paul Erdős and the Search for Mathematical Truth|author = Hoffman, P.|publisher = Hyperion, New York| year = 1998|isbn=1857028295}} | |||

| ===Works cited=== | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Boolos |first1=George |author-link1=George Boolos|last2=Burgess |first2=John |author-link2=John P. Burgess|last3=Jeffrey |first3=Richard |title=Computability and Logic |date=2007 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |edition=5th}} | |||

| | last = Hofstadter | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Enderton |first1=Herbert |author-link=Herbert Enderton|title=A Mathematical Introduction to Logic |date=2001 |publisher=Harcourt Academic Press |edition=2nd}} | |||

| | first = Douglas | |||

| * {{Cite book|author-link=Thomas Heath (classicist)|title=The works of Archimedes|last=Heath|first=Sir Thomas Little|publisher=Dover|year=1897|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FIY5AAAAMAAJ&q=theorem|access-date=2009-11-15}} | |||

| | authorlink = Douglas Hofstadter | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Hedman |first1=Shawn |title=A First Course in Logic |date=2004 |publisher=Oxford University Press}} | |||

| | title = ]: An Eternal Golden Braid | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Hinman |first1=Peter |title=Fundamentals of Mathematical Logic |date=2005 |publisher=A K Peters |location=Wellesley, MA}} | |||

| | publisher = Basic Books | |||

| * {{Cite book|title = ]: The Story of Paul Erdős and the Search for Mathematical Truth|last = Hoffman |first=Paul |author-link=Paul Hoffman|publisher = Hyperion, New York| year = 1998|isbn=1-85702-829-5}} | |||

| | year = {{year?}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Hodges |first1=Wilfrid |author-link=Wilfrid Hodges |title=Model Theory |date=1993 |publisher=Cambridge University Press}} | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{ |

* {{cite book |last1=Johnstone |first1=P. T. |title=Notes on Logic and Set Theory |date=1987 |publisher=Cambridge University Press}} | ||

| * {{ |

* {{cite book |last1=Monk |first1=J. Donald |title=Mathematical Logic |date=1976 |publisher=Springer-Verlag}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|title |

* {{Cite book|title=A = B|url=https://dissertationeditinghelp.com/aeqb/|last=Petkovsek |first1= Marko|last2=Wilf |first2=Herbert|last3=Zeilberger|first3=Doron|publisher=A.K. Peters, Wellesley, Massachusetts|year=1996|isbn=1-56881-063-6}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Rautenberg |first1=Wolfgang |title=A Concise Introduction to Mathematical Logic |date=2010 |publisher=Springer |edition=3rd}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=van Dalen |first1=Dirk |title=Logic and Structure |date=1994 |publisher=Springer-Verlag|edition=3rd}} | |||

| * {{cite book|first1=G. |last1=Wentworth |first2=D.E. |last2=Smith |year=1913 |title=Plane Geometry |publisher=Ginn & Co. |url=https://archive.org/details/planegeometry00gwen}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Chiswell |first1=Ian |last2=Hodges |first2=Wilfred |title=Mathematical Logic |date=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press}} | |||

| * {{Hunter 1996}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Mates|first=Benson|author-link=Benson Mates|title=Elementary Logic|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1972|isbn=0-19-501491-X|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/elementarylogic00mate}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Wiktionary|theorem}} | {{Wiktionary|theorem}} | ||

| *{{Commons category-inline|Theorems}} | |||

| *{{MathWorld|title=Theorem|urlname=Theorem}} | |||

| *{{MathWorld |title=Theorem |urlname=Theorem}} | |||

| * | * | ||

| {{ |

{{Logical truth}} | ||

| {{Mathematical logic}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2010}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:38, 1 December 2024

In mathematics, a statement that has been proven Not to be confused with Teorema, Theorema, or Theory.

In mathematics and formal logic, a theorem is a statement that has been proven, or can be proven. The proof of a theorem is a logical argument that uses the inference rules of a deductive system to establish that the theorem is a logical consequence of the axioms and previously proved theorems.

In mainstream mathematics, the axioms and the inference rules are commonly left implicit, and, in this case, they are almost always those of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice (ZFC), or of a less powerful theory, such as Peano arithmetic. Generally, an assertion that is explicitly called a theorem is a proved result that is not an immediate consequence of other known theorems. Moreover, many authors qualify as theorems only the most important results, and use the terms lemma, proposition and corollary for less important theorems.

In mathematical logic, the concepts of theorems and proofs have been formalized in order to allow mathematical reasoning about them. In this context, statements become well-formed formulas of some formal language. A theory consists of some basis statements called axioms, and some deducing rules (sometimes included in the axioms). The theorems of the theory are the statements that can be derived from the axioms by using the deducing rules. This formalization led to proof theory, which allows proving general theorems about theorems and proofs. In particular, Gödel's incompleteness theorems show that every consistent theory containing the natural numbers has true statements on natural numbers that are not theorems of the theory (that is they cannot be proved inside the theory).

As the axioms are often abstractions of properties of the physical world, theorems may be considered as expressing some truth, but in contrast to the notion of a scientific law, which is experimental, the justification of the truth of a theorem is purely deductive. A conjecture is a tentative proposition that may evolve to become a theorem if proven true.

Theoremhood and truth

Until the end of the 19th century and the foundational crisis of mathematics, all mathematical theories were built from a few basic properties that were considered as self-evident; for example, the facts that every natural number has a successor, and that there is exactly one line that passes through two given distinct points. These basic properties that were considered as absolutely evident were called postulates or axioms; for example Euclid's postulates. All theorems were proved by using implicitly or explicitly these basic properties, and, because of the evidence of these basic properties, a proved theorem was considered as a definitive truth, unless there was an error in the proof. For example, the sum of the interior angles of a triangle equals 180°, and this was considered as an undoubtable fact.

One aspect of the foundational crisis of mathematics was the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries that do not lead to any contradiction, although, in such geometries, the sum of the angles of a triangle is different from 180°. So, the property "the sum of the angles of a triangle equals 180°" is either true or false, depending whether Euclid's fifth postulate is assumed or denied. Similarly, the use of "evident" basic properties of sets leads to the contradiction of Russell's paradox. This has been resolved by elaborating the rules that are allowed for manipulating sets.

This crisis has been resolved by revisiting the foundations of mathematics to make them more rigorous. In these new foundations, a theorem is a well-formed formula of a mathematical theory that can be proved from the axioms and inference rules of the theory. So, the above theorem on the sum of the angles of a triangle becomes: Under the axioms and inference rules of Euclidean geometry, the sum of the interior angles of a triangle equals 180°. Similarly, Russell's paradox disappears because, in an axiomatized set theory, the set of all sets cannot be expressed with a well-formed formula. More precisely, if the set of all sets can be expressed with a well-formed formula, this implies that the theory is inconsistent, and every well-formed assertion, as well as its negation, is a theorem.

In this context, the validity of a theorem depends only on the correctness of its proof. It is independent from the truth, or even the significance of the axioms. This does not mean that the significance of the axioms is uninteresting, but only that the validity of a theorem is independent from the significance of the axioms. This independence may be useful by allowing the use of results of some area of mathematics in apparently unrelated areas.

An important consequence of this way of thinking about mathematics is that it allows defining mathematical theories and theorems as mathematical objects, and to prove theorems about them. Examples are Gödel's incompleteness theorems. In particular, there are well-formed assertions than can be proved to not be a theorem of the ambient theory, although they can be proved in a wider theory. An example is Goodstein's theorem, which can be stated in Peano arithmetic, but is proved to be not provable in Peano arithmetic. However, it is provable in some more general theories, such as Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory.

Epistemological considerations

Many mathematical theorems are conditional statements, whose proofs deduce conclusions from conditions known as hypotheses or premises. In light of the interpretation of proof as justification of truth, the conclusion is often viewed as a necessary consequence of the hypotheses. Namely, that the conclusion is true in case the hypotheses are true—without any further assumptions. However, the conditional could also be interpreted differently in certain deductive systems, depending on the meanings assigned to the derivation rules and the conditional symbol (e.g., non-classical logic).

Although theorems can be written in a completely symbolic form (e.g., as propositions in propositional calculus), they are often expressed informally in a natural language such as English for better readability. The same is true of proofs, which are often expressed as logically organized and clearly worded informal arguments, intended to convince readers of the truth of the statement of the theorem beyond any doubt, and from which a formal symbolic proof can in principle be constructed.

In addition to the better readability, informal arguments are typically easier to check than purely symbolic ones—indeed, many mathematicians would express a preference for a proof that not only demonstrates the validity of a theorem, but also explains in some way why it is obviously true. In some cases, one might even be able to substantiate a theorem by using a picture as its proof.

Because theorems lie at the core of mathematics, they are also central to its aesthetics. Theorems are often described as being "trivial", or "difficult", or "deep", or even "beautiful". These subjective judgments vary not only from person to person, but also with time and culture: for example, as a proof is obtained, simplified or better understood, a theorem that was once difficult may become trivial. On the other hand, a deep theorem may be stated simply, but its proof may involve surprising and subtle connections between disparate areas of mathematics. Fermat's Last Theorem is a particularly well-known example of such a theorem.

Informal account of theorems

Logically, many theorems are of the form of an indicative conditional: If A, then B. Such a theorem does not assert B — only that B is a necessary consequence of A. In this case, A is called the hypothesis of the theorem ("hypothesis" here means something very different from a conjecture), and B the conclusion of the theorem. The two together (without the proof) are called the proposition or statement of the theorem (e.g. "If A, then B" is the proposition). Alternatively, A and B can be also termed the antecedent and the consequent, respectively. The theorem "If n is an even natural number, then n/2 is a natural number" is a typical example in which the hypothesis is "n is an even natural number", and the conclusion is "n/2 is also a natural number".

In order for a theorem to be proved, it must be in principle expressible as a precise, formal statement. However, theorems are usually expressed in natural language rather than in a completely symbolic form—with the presumption that a formal statement can be derived from the informal one.

It is common in mathematics to choose a number of hypotheses within a given language and declare that the theory consists of all statements provable from these hypotheses. These hypotheses form the foundational basis of the theory and are called axioms or postulates. The field of mathematics known as proof theory studies formal languages, axioms and the structure of proofs.

Some theorems are "trivial", in the sense that they follow from definitions, axioms, and other theorems in obvious ways and do not contain any surprising insights. Some, on the other hand, may be called "deep", because their proofs may be long and difficult, involve areas of mathematics superficially distinct from the statement of the theorem itself, or show surprising connections between disparate areas of mathematics. A theorem might be simple to state and yet be deep. An excellent example is Fermat's Last Theorem, and there are many other examples of simple yet deep theorems in number theory and combinatorics, among other areas.

Other theorems have a known proof that cannot easily be written down. The most prominent examples are the four color theorem and the Kepler conjecture. Both of these theorems are only known to be true by reducing them to a computational search that is then verified by a computer program. Initially, many mathematicians did not accept this form of proof, but it has become more widely accepted. The mathematician Doron Zeilberger has even gone so far as to claim that these are possibly the only nontrivial results that mathematicians have ever proved. Many mathematical theorems can be reduced to more straightforward computation, including polynomial identities, trigonometric identities and hypergeometric identities.

Relation with scientific theories

Theorems in mathematics and theories in science are fundamentally different in their epistemology. A scientific theory cannot be proved; its key attribute is that it is falsifiable, that is, it makes predictions about the natural world that are testable by experiments. Any disagreement between prediction and experiment demonstrates the incorrectness of the scientific theory, or at least limits its accuracy or domain of validity. Mathematical theorems, on the other hand, are purely abstract formal statements: the proof of a theorem cannot involve experiments or other empirical evidence in the same way such evidence is used to support scientific theories.

Nonetheless, there is some degree of empiricism and data collection involved in the discovery of mathematical theorems. By establishing a pattern, sometimes with the use of a powerful computer, mathematicians may have an idea of what to prove, and in some cases even a plan for how to set about doing the proof. It is also possible to find a single counter-example and so establish the impossibility of a proof for the proposition as-stated, and possibly suggest restricted forms of the original proposition that might have feasible proofs.

For example, both the Collatz conjecture and the Riemann hypothesis are well-known unsolved problems; they have been extensively studied through empirical checks, but remain unproven. The Collatz conjecture has been verified for start values up to about 2.88 × 10. The Riemann hypothesis has been verified to hold for the first 10 trillion non-trivial zeroes of the zeta function. Although most mathematicians can tolerate supposing that the conjecture and the hypothesis are true, neither of these propositions is considered proved.

Such evidence does not constitute proof. For example, the Mertens conjecture is a statement about natural numbers that is now known to be false, but no explicit counterexample (i.e., a natural number n for which the Mertens function M(n) equals or exceeds the square root of n) is known: all numbers less than 10 have the Mertens property, and the smallest number that does not have this property is only known to be less than the exponential of 1.59 × 10, which is approximately 10 to the power 4.3 × 10. Since the number of particles in the universe is generally considered less than 10 to the power 100 (a googol), there is no hope to find an explicit counterexample by exhaustive search.

The word "theory" also exists in mathematics, to denote a body of mathematical axioms, definitions and theorems, as in, for example, group theory (see mathematical theory). There are also "theorems" in science, particularly physics, and in engineering, but they often have statements and proofs in which physical assumptions and intuition play an important role; the physical axioms on which such "theorems" are based are themselves falsifiable.

Terminology

A number of different terms for mathematical statements exist; these terms indicate the role statements play in a particular subject. The distinction between different terms is sometimes rather arbitrary, and the usage of some terms has evolved over time.

- An axiom or postulate is a fundamental assumption regarding the object of study, that is accepted without proof. A related concept is that of a definition, which gives the meaning of a word or a phrase in terms of known concepts. Classical geometry discerns between axioms, which are general statements; and postulates, which are statements about geometrical objects. Historically, axioms were regarded as "self-evident"; today they are merely assumed to be true.

- A conjecture is an unproved statement that is believed to be true. Conjectures are usually made in public, and named after their maker (for example, Goldbach's conjecture and Collatz conjecture). The term hypothesis is also used in this sense (for example, Riemann hypothesis), which should not be confused with "hypothesis" as the premise of a proof. Other terms are also used on occasion, for example problem when people are not sure whether the statement should be believed to be true. Fermat's Last Theorem was historically called a theorem, although, for centuries, it was only a conjecture.

- A theorem is a statement that has been proven to be true based on axioms and other theorems.

- A proposition is a theorem of lesser importance, or one that is considered so elementary or immediately obvious, that it may be stated without proof. This should not be confused with "proposition" as used in propositional logic. In classical geometry the term "proposition" was used differently: in Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BCE), all theorems and geometric constructions were called "propositions" regardless of their importance.

- A lemma is an "accessory proposition" - a proposition with little applicability outside its use in a particular proof. Over time a lemma may gain in importance and be considered a theorem, though the term "lemma" is usually kept as part of its name (e.g. Gauss's lemma, Zorn's lemma, and the fundamental lemma).

- A corollary is a proposition that follows immediately from another theorem or axiom, with little or no required proof. A corollary may also be a restatement of a theorem in a simpler form, or for a special case: for example, the theorem "all internal angles in a rectangle are right angles" has a corollary that "all internal angles in a square are right angles" - a square being a special case of a rectangle.

- A generalization of a theorem is a theorem with a similar statement but a broader scope, from which the original theorem can be deduced as a special case (a corollary).

Other terms may also be used for historical or customary reasons, for example:

- An identity is a theorem stating an equality between two expressions, that holds for any value within its domain (e.g. Bézout's identity and Vandermonde's identity).

- A rule is a theorem that establishes a useful formula (e.g. Bayes' rule and Cramer's rule).

- A law or principle is a theorem with wide applicability (e.g. the law of large numbers, law of cosines, Kolmogorov's zero–one law, Harnack's principle, the least-upper-bound principle, and the pigeonhole principle).

A few well-known theorems have even more idiosyncratic names, for example, the division algorithm, Euler's formula, and the Banach–Tarski paradox.

Layout

A theorem and its proof are typically laid out as follows:

- Theorem (name of the person who proved it, along with year of discovery or publication of the proof)

- Statement of theorem (sometimes called the proposition)

- Proof

- Description of proof

- End

The end of the proof may be signaled by the letters Q.E.D. (quod erat demonstrandum) or by one of the tombstone marks, such as "□" or "∎", meaning "end of proof", introduced by Paul Halmos following their use in magazines to mark the end of an article.

The exact style depends on the author or publication. Many publications provide instructions or macros for typesetting in the house style.

It is common for a theorem to be preceded by definitions describing the exact meaning of the terms used in the theorem. It is also common for a theorem to be preceded by a number of propositions or lemmas which are then used in the proof. However, lemmas are sometimes embedded in the proof of a theorem, either with nested proofs, or with their proofs presented after the proof of the theorem.

Corollaries to a theorem are either presented between the theorem and the proof, or directly after the proof. Sometimes, corollaries have proofs of their own that explain why they follow from the theorem.

Lore

It has been estimated that over a quarter of a million theorems are proved every year.

The well-known aphorism, "A mathematician is a device for turning coffee into theorems", is probably due to Alfréd Rényi, although it is often attributed to Rényi's colleague Paul Erdős (and Rényi may have been thinking of Erdős), who was famous for the many theorems he produced, the number of his collaborations, and his coffee drinking.

The classification of finite simple groups is regarded by some to be the longest proof of a theorem. It comprises tens of thousands of pages in 500 journal articles by some 100 authors. These papers are together believed to give a complete proof, and several ongoing projects hope to shorten and simplify this proof. Another theorem of this type is the four color theorem whose computer generated proof is too long for a human to read. It is among the longest known proofs of a theorem whose statement can be easily understood by a layman.

Theorems in logic

In mathematical logic, a formal theory is a set of sentences within a formal language. A sentence is a well-formed formula with no free variables. A sentence that is a member of a theory is one of its theorems, and the theory is the set of its theorems. Usually a theory is understood to be closed under the relation of logical consequence. Some accounts define a theory to be closed under the semantic consequence relation (), while others define it to be closed under the syntactic consequence, or derivability relation ().

For a theory to be closed under a derivability relation, it must be associated with a deductive system that specifies how the theorems are derived. The deductive system may be stated explicitly, or it may be clear from the context. The closure of the empty set under the relation of logical consequence yields the set that contains just those sentences that are the theorems of the deductive system.

In the broad sense in which the term is used within logic, a theorem does not have to be true, since the theory that contains it may be unsound relative to a given semantics, or relative to the standard interpretation of the underlying language. A theory that is inconsistent has all sentences as theorems.

The definition of theorems as sentences of a formal language is useful within proof theory, which is a branch of mathematics that studies the structure of formal proofs and the structure of provable formulas. It is also important in model theory, which is concerned with the relationship between formal theories and structures that are able to provide a semantics for them through interpretation.

Although theorems may be uninterpreted sentences, in practice mathematicians are more interested in the meanings of the sentences, i.e. in the propositions they express. What makes formal theorems useful and interesting is that they may be interpreted as true propositions and their derivations may be interpreted as a proof of their truth. A theorem whose interpretation is a true statement about a formal system (as opposed to within a formal system) is called a metatheorem.

Some important theorems in mathematical logic are:

- Compactness of first-order logic

- Completeness of first-order logic

- Gödel's incompleteness theorems of first-order arithmetic

- Consistency of first-order arithmetic

- Tarski's undefinability theorem

- Church-Turing theorem of undecidability

- Löb's theorem

- Löwenheim–Skolem theorem

- Lindström's theorem

- Craig's theorem

- Cut-elimination theorem

Syntax and semantics

Main articles: Syntax (logic) and Formal semantics (logic)The concept of a formal theorem is fundamentally syntactic, in contrast to the notion of a true proposition, which introduces semantics. Different deductive systems can yield other interpretations, depending on the presumptions of the derivation rules (i.e. belief, justification or other modalities). The soundness of a formal system depends on whether or not all of its theorems are also validities. A validity is a formula that is true under any possible interpretation (for example, in classical propositional logic, validities are tautologies). A formal system is considered semantically complete when all of its theorems are also tautologies.

Interpretation of a formal theorem

Main article: Interpretation (logic)Theorems and theories

Main articles: Theory and Theory (mathematical logic)See also

- Law (mathematics)

- List of theorems

- List of theorems called fundamental

- Formula

- Inference

- Toy theorem

Citations

Notes

- In general, the distinction is weak, as the standard way to prove that a statement is provable consists of proving it. However, in mathematical logic, one considers often the set of all theorems of a theory, although one cannot prove them individually.

- An exception is the original Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, which relies implicitly on Grothendieck universes, whose existence requires the addition of a new axiom to set theory. This reliance on a new axiom of set theory has since been removed. Nevertheless, it is rather astonishing that the first proof of a statement expressed in elementary arithmetic involves the existence of very large infinite sets.

- A theory is often identified with the set of its theorems. This is avoided here for clarity, and also for not depending on set theory.

- However, both theorems and scientific law are the result of investigations. See Heath 1897, p. clxxxii, Introduction, The terminology of Archimedes: "theorem (θεὼρνμα) from θεωρεἳν to investigate"

- Such as the derivation of the formula for from the addition formulas of sine and cosine.

- Often, when the less general or "corollary"-like theorem is proven first, it is because the proof of the more general form requires the simpler, corollary-like form, for use as a what is functionally a lemma, or "helper" theorem.

- The word law can also refer to an axiom, a rule of inference, or, in probability theory, a probability distribution.

References

- Elisha Scott Loomis. "The Pythagorean proposition: its demonstrations analyzed and classified, and bibliography of sources for data of the four kinds of proofs" (PDF). Education Resources Information Center. Institute of Education Sciences (IES) of the U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved 2010-09-26. Originally published in 1940 and reprinted in 1968 by National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

- "Theorem". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- "Theorem | Definition of Theorem by Lexico". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- McLarty, Colin (2010). "What does it take to prove Fermat's last theorem? Grothendieck and the logic of number theory". The Review of Symbolic Logic. 13 (3). Cambridge University Press: 359–377. doi:10.2178/bsl/1286284558. S2CID 13475845.

- McLarty, Colin (2020). "The large structures of Grothendieck founded on finite order arithmetic". Bulletin of Symbolic Logic. 16 (2). Cambridge University Press: 296–325. arXiv:1102.1773. doi:10.1017/S1755020319000340. S2CID 118395028.

- ^ Markie, Peter (2017), "Rationalism vs. Empiricism", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2019-11-02

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Theorem". MathWorld.

- ^ Darmon, Henri; Diamond, Fred; Taylor, Richard (2007-09-09). "Fermat's Last Theorem" (PDF). McGill University – Department of Mathematics and Statistics. Retrieved 2019-11-01.