This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Iztwoz (talk | contribs) at 12:06, 6 June 2021 (→Structure: separated out invertebrate info). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:06, 6 June 2021 by Iztwoz (talk | contribs) (→Structure: separated out invertebrate info)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Muscle (muscle) (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Mussel. Contractile soft tissue in animals

| Muscle | |

|---|---|

A top-down view of skeletal muscle A top-down view of skeletal muscle | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Mesoderm |

| System | Musculoskeletal system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus |

| Anatomical terminology[edit on Wikidata] | |

Muscle is a soft tissue found in most animals, and is one of the four basic animal tissues, along with nervous tissue, epithelium, and connective tissue. Muscle cells contain protein filaments called myofilaments of actin and myosin that slide past one another, producing a contraction that changes both the length and the shape of the cell. Muscles function to produce force and motion. They are primarily responsible for maintaining and changing posture, locomotion, as well as movement of internal organs, such as the contraction of the heart and the movement of food through the digestive system via peristalsis.

Muscle tissue is derived from the embryonic mesodermal germ layer in a process known as myogenesis. There are three types of muscle, of which skeletal and cardiac muscle are striated and smooth muscle is not. Muscle action can be classified as being either voluntary or involuntary. Cardiac and smooth muscles contract without conscious thought and are termed involuntary, whereas the skeletal muscles contract upon command. Skeletal muscles in turn can be divided into fast and slow twitch fibers.

Muscles are predominantly powered by the oxidation of fats and carbohydrates, but anaerobic chemical reactions are also used, particularly by fast twitch fibers. These chemical reactions produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules that are used to power the movement of the myosin heads.

The term muscle is derived from the Latin musculus meaning "little mouse" perhaps because of the shape of certain skeletal muscles or because contracting muscles look like mice moving under the skin.

Structure

The anatomy of muscles includes gross anatomy, which comprises all the muscles of an organism, and microanatomy, which comprises the structure of a single muscle.

Types

Main article: Muscle tissue

Muscle tissue is a soft tissue, and is one of the four fundamental types of tissue present in animals. There are three types of muscle tissue recognized in vertebrates:

- Skeletal muscle or "voluntary muscle" is anchored by tendons (or by aponeuroses at a few places) to bone and is used to effect skeletal movement such as locomotion and in maintaining posture. Though this postural control is generally maintained as an unconscious reflex, the muscles responsible react to conscious control like non-postural muscles. An average adult male is made up of 42% of skeletal muscle and an average adult female is made up of 36% (as a percentage of body mass).

- Smooth muscle or "involuntary muscle" is found within the walls of organs and structures such as the esophagus, stomach, intestines, bronchi, uterus, urethra, bladder, blood vessels, and the arrector pili in the skin (in which it controls erection of body hair). Unlike skeletal muscle, smooth muscle is not under conscious control.

- Cardiac muscle (myocardium), is also an "involuntary muscle" but is more akin in structure to skeletal muscle, and is found only in the heart.

Cardiac and skeletal muscles are "striated" in that they contain sarcomeres that are packed into highly regular arrangements of bundles; the myofibrils of smooth muscle cells are not arranged in sarcomeres and so are not striated. While the sarcomeres in skeletal muscles are arranged in regular, parallel bundles, cardiac muscle sarcomeres connect at branching, irregular angles (called intercalated discs). Striated muscle contracts and relaxes in short, intense bursts, whereas smooth muscle sustains longer or even near-permanent contractions.

Skeletal muscle fiber types

The muscle fibers embedded in skeletal muscle are relatively classified into a spectrum of types given their morphological and physiological properties. Given a certain assortment of these properties, muscle fibers are categorized as slow-twitch (low force, slowly fatiguing fibers), fast twitch (high force, rapidly fatiguing fibers), or somewhere in between those two types (i.e. intermediate fibers). Some of the defining morphological and physiological properties used for the categorization of muscle fibers include: the number of mitochondria contained in the fiber, the amount of glycolytic, lipolytic, and other cellular respiration enzymes, M and Z band characteristics, energy source (i.e. glycogen or fat), histology color, and contraction speed and duration. There is no standard procedure for classifying muscle fiber types, the properties chosen for classification depends on the particular muscle.

- Type I, slow twitch, or "red" muscle, is dense with capillaries and is rich in mitochondria and myoglobin, giving the muscle tissue its characteristic red color. It can carry more oxygen and sustain aerobic activity using fats or carbohydrates as fuel. Slow twitch fibers contract for long periods of time but with little force.

- Type II, fast twitch muscle, has three major subtypes (IIa, IIx, and IIb) that vary in both contractile speed and force generated. Fast twitch fibers contract quickly and powerfully but fatigue very rapidly, sustaining only short, anaerobic bursts of activity before muscle contraction becomes painful. They contribute most to muscle strength and have greater potential for increase in mass. Type IIb is anaerobic, glycolytic, "white" muscle that is least dense in mitochondria and myoglobin. In small animals (e.g., rodents) this is the major fast muscle type, explaining the pale color of their flesh.

Invertebrate muscle cell types

The properties used for distinguishing fast, intermediate, and slow muscle fibers can be different for invertebrate flight and jump muscle. To further complicate this classification scheme, the mitochondria content and other morphological properties within a muscle fiber can change in a tsetse fly with exercise and age.

Microanatomy

Main articles: Muscle cell and Sarcomere

Skeletal muscles are sheathed by a tough layer of connective tissue called the epimysium. The epimysium anchors muscle tissue to tendons at each end, where the epimysium becomes thicker and collagenous. It also protects muscles from friction against other muscles and bones. Within the epimysium are multiple bundles called fascicles, each of which contains 10 to 100 or more muscle fibers collectively sheathed by a perimysium. Besides surrounding each fascicle, the perimysium is a pathway for nerves and the flow of blood within the muscle. The threadlike muscle fibers are the individual muscle cells, and each cell is encased within its own endomysium of collagen fibers. Thus, the overall muscle consists of fibers (cells) that are bundled into fascicles, which are themselves grouped together to form muscles. At each level of bundling, a collagenous membrane surrounds the bundle, and these membranes support muscle function both by resisting passive stretching of the tissue and by distributing forces applied to the muscle. Scattered throughout the muscles are muscle spindles that provide sensory feedback information to the central nervous system. (This grouping structure is analogous to the organization of nerves which uses epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium).

This same bundles-within-bundles structure is replicated within the muscle cells. Within the cells of the muscle are myofibrils, which themselves are bundles of protein filaments. The term "myofibril" should not be confused with "myofiber", which is a simply another name for a muscle cell. Myofibrils are complex strands of several kinds of protein filaments organized together into repeating units called sarcomeres. The striated appearance of both skeletal and cardiac muscle results from the regular pattern of sarcomeres within their cells. Although both of these types of muscle contain sarcomeres, the fibers in cardiac muscle are typically branched to form a network. Cardiac muscle cells are interconnected by intercalated discs, giving that tissue the appearance of a syncytium.

The filaments in a sarcomere are composed of actin and myosin.

Gross anatomy

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The gross anatomy of a muscle is the most important indicator of its role in the body. There is an important distinction seen between pennate muscles and other muscles. In most muscles, all the fibers are oriented in the same direction, running in a line from the origin to the insertion. However, In pennate muscles, the individual fibers are oriented at an angle relative to the line of action, attaching to the origin and insertion tendons at each end. Because the contracting fibers are pulling at an angle to the overall action of the muscle, the change in length is smaller, but this same orientation allows for more fibers (thus more force) in a muscle of a given size. Pennate muscles are usually found where their length change is less important than maximum force, such as the rectus femoris.

Skeletal muscle tissue is arranged in discrete muscles, an example of which is the biceps. The tough, fibrous epimysium of skeletal muscle is both connected to and continuous with the tendons. In turn, the tendons connect to the periosteum layer surrounding the bones, permitting the transfer of force from the muscles to the skeleton. Together, these fibrous layers, along with tendons and ligaments, constitute the deep fascia of the body.

Muscular system

Main article: Muscular system

The muscular system consists of all the muscles present in a body. There are approximately 650 skeletal muscles in the human body, but an exact number is difficult to define. The difficulty lies partly in the fact that different sources group the muscles differently and partly in that some muscles, such as the palmaris longus, are not always present.

A muscular slip is a narrow length of muscle that acts to augment a larger muscle or muscles.

In the human the muscular system is one component of the musculoskeletal system, which includes not only the muscles but also the bones, joints, tendons, and other structures that permit movement.

Development

Main article: Myogenesis

All muscles are derived from paraxial mesoderm. The paraxial mesoderm is divided along the embryo's length into somites, corresponding to the segmentation of the body (most obviously seen in the vertebral column. Each somite has 3 divisions, sclerotome (which forms vertebrae), dermatome (which forms skin), and myotome (which forms muscle). The myotome is divided into two sections, the epimere and hypomere, which form epaxial and hypaxial muscles, respectively. The only epaxial muscles in humans are the erector spinae and small intervertebral muscles, and are innervated by the dorsal rami of the spinal nerves. All other muscles, including those of the limbs are hypaxial, and innervated by the ventral rami of the spinal nerves.

During development, myoblasts (muscle progenitor cells) either remain in the somite to form muscles associated with the vertebral column or migrate out into the body to form all other muscles. Myoblast migration is preceded by the formation of connective tissue frameworks, usually formed from the somatic lateral plate mesoderm. Myoblasts follow chemical signals to the appropriate locations, where they fuse into elongate skeletal muscle cells.

Physiology

Contraction

Main article: Muscle contractionThe three types of muscle (skeletal, cardiac and smooth) have significant differences. However, all three use the movement of actin against myosin to create contraction. In skeletal muscle, contraction is stimulated by electrical impulses transmitted by the nerves, the motor neurons in particular. Cardiac and smooth muscle contractions are stimulated by internal pacemaker cells which regularly contract, and propagate contractions to other muscle cells they are in contact with. All skeletal muscle and many smooth muscle contractions are facilitated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

The action a muscle generates is determined by the origin and insertion locations. The cross-sectional area of a muscle (rather than volume or length) determines the amount of force it can generate by defining the number of sarcomeres which can operate in parallel. Each skeletal muscle contains long units called myofibrils, and each myofibril is a chain of sarcomeres. Since contraction occurs at the same time for all connected sarcomeres in a muscles cell, these chains of sarcomeres shorten together, thus shortening the muscle fiber, resulting in overall length change. The amount of force applied to the external environment is determined by lever mechanics, specifically the ratio of in-lever to out-lever. For example, moving the insertion point of the biceps more distally on the radius (farther from the joint of rotation) would increase the force generated during flexion (and, as a result, the maximum weight lifted in this movement), but decrease the maximum speed of flexion. Moving the insertion point proximally (closer to the joint of rotation) would result in decreased force but increased velocity. This can be most easily seen by comparing the limb of a mole to a horse—in the former, the insertion point is positioned to maximize force (for digging), while in the latter, the insertion point is positioned to maximize speed (for running).

Nervous control

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Muscle movement

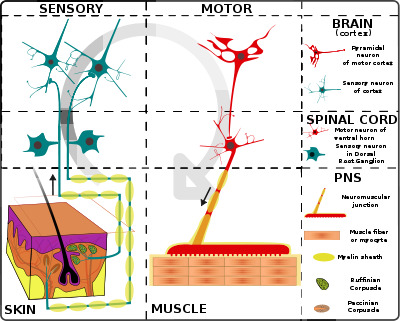

The efferent leg of the peripheral nervous system is responsible for conveying commands to the muscles and glands, and is ultimately responsible for voluntary movement. Nerves move muscles in response to voluntary and autonomic (involuntary) signals from the brain. Deep muscles, superficial muscles, muscles of the face and internal muscles all correspond with dedicated regions in the primary motor cortex of the brain, directly anterior to the central sulcus that divides the frontal and parietal lobes.

In addition, muscles react to reflexive nerve stimuli that do not always send signals all the way to the brain. In this case, the signal from the afferent fiber does not reach the brain, but produces the reflexive movement by direct connections with the efferent nerves in the spine. However, the majority of muscle activity is volitional, and the result of complex interactions between various areas of the brain.

Nerves that control skeletal muscles in mammals correspond with neuron groups along the primary motor cortex of the brain's cerebral cortex. Commands are routed through the basal ganglia and are modified by input from the cerebellum before being relayed through the pyramidal tract to the spinal cord and from there to the motor end plate at the muscles. Along the way, feedback, such as that of the extrapyramidal system contribute signals to influence muscle tone and response.

Deeper muscles such as those involved in posture often are controlled from nuclei in the brain stem and basal ganglia.

Proprioception

Main article: ProprioceptionIn skeletal muscles, muscle spindles convey information about the degree of muscle length and stretch to the central nervous system to assist in maintaining posture and joint position. The sense of where our bodies are in space is called proprioception, the perception of body awareness, the "unconscious" awareness of where the various regions of the body are located at any one time. Several areas in the brain coordinate movement and position with the feedback information gained from proprioception. The cerebellum and red nucleus in particular continuously sample position against movement and make minor corrections to assure smooth motion.

Energy consumption

Main article: Bioenergetic systems

Muscular activity accounts for much of the body's energy consumption. All muscle cells produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules which are used to power the movement of the myosin heads. Muscles have a short-term store of energy in the form of creatine phosphate which is generated from ATP and can regenerate ATP when needed with creatine kinase. Muscles also keep a storage form of glucose in the form of glycogen. Glycogen can be rapidly converted to glucose when energy is required for sustained, powerful contractions. Within the voluntary skeletal muscles, the glucose molecule can be metabolized anaerobically in a process called glycolysis which produces two ATP and two lactic acid molecules in the process (note that in aerobic conditions, lactate is not formed; instead pyruvate is formed and transmitted through the citric acid cycle). Muscle cells also contain globules of fat, which are used for energy during aerobic exercise. The aerobic energy systems take longer to produce the ATP and reach peak efficiency, and requires many more biochemical steps, but produces significantly more ATP than anaerobic glycolysis. Cardiac muscle on the other hand, can readily consume any of the three macronutrients (protein, glucose and fat) aerobically without a 'warm up' period and always extracts the maximum ATP yield from any molecule involved. The heart, liver and red blood cells will also consume lactic acid produced and excreted by skeletal muscles during exercise.

At rest, skeletal muscle consumes 54.4 kJ/kg (13.0 kcal/kg) per day. This is larger than adipose tissue (fat) at 18.8 kJ/kg (4.5 kcal/kg), and bone at 9.6 kJ/kg (2.3 kcal/kg).

Efficiency

The efficiency of human muscle has been measured (in the context of rowing and cycling) at 18% to 26%. The efficiency is defined as the ratio of mechanical work output to the total metabolic cost, as can be calculated from oxygen consumption. This low efficiency is the result of about 40% efficiency of generating ATP from food energy, losses in converting energy from ATP into mechanical work inside the muscle, and mechanical losses inside the body. The latter two losses are dependent on the type of exercise and the type of muscle fibers being used (fast-twitch or slow-twitch). For an overall efficiency of 20 percent, one watt of mechanical power is equivalent to 4.3 kcal per hour. For example, one manufacturer of rowing equipment calibrates its rowing ergometer to count burned calories as equal to four times the actual mechanical work, plus 300 kcal per hour, this amounts to about 20 percent efficiency at 250 watts of mechanical output. The mechanical energy output of a cyclic contraction can depend upon many factors, including activation timing, muscle strain trajectory, and rates of force rise & decay. These can be synthesized experimentally using work loop analysis.

Strength

Muscle is a result of three factors that overlap: physiological strength (muscle size, cross sectional area, available crossbridging, responses to training), neurological strength (how strong or weak is the signal that tells the muscle to contract), and mechanical strength (muscle's force angle on the lever, moment arm length, joint capabilities).

Physiological strength

Main article: Physical strength| Grade 0 | No contraction |

| Grade 1 | Trace of contraction, but no movement at the joint |

| Grade 2 | Movement at the joint with gravity eliminated |

| Grade 3 | Movement against gravity, but not against added resistance |

| Grade 4 | Movement against external resistance, but less than normal |

| Grade 5 | Normal strength |

Vertebrate muscle typically produces approximately 25–33 N (5.6–7.4 lbf) of force per square centimeter of muscle cross-sectional area when isometric and at optimal length. Some invertebrate muscles, such as in crab claws, have much longer sarcomeres than vertebrates, resulting in many more sites for actin and myosin to bind and thus much greater force per square centimeter at the cost of much slower speed. The force generated by a contraction can be measured non-invasively using either mechanomyography or phonomyography, be measured in vivo using tendon strain (if a prominent tendon is present), or be measured directly using more invasive methods.

The strength of any given muscle, in terms of force exerted on the skeleton, depends upon length, shortening speed, cross sectional area, pennation, sarcomere length, myosin isoforms, and neural activation of motor units. Significant reductions in muscle strength can indicate underlying pathology, with the chart at right used as a guide.

The "strongest" human muscle

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Since three factors affect muscular strength simultaneously and muscles never work individually, it is misleading to compare strength in individual muscles, and state that one is the "strongest". But below are several muscles whose strength is noteworthy for different reasons.

- In ordinary parlance, muscular "strength" usually refers to the ability to exert a force on an external object—for example, lifting a weight. By this definition, the masseter or jaw muscle is the strongest. The 1992 Guinness Book of Records records the achievement of a bite strength of 4,337 N (975 lbf) for 2 seconds. What distinguishes the masseter is not anything special about the muscle itself, but its advantage in working against a much shorter lever arm than other muscles.

- If "strength" refers to the force exerted by the muscle itself, e.g., on the place where it inserts into a bone, then the strongest muscles are those with the largest cross-sectional area. This is because the tension exerted by an individual skeletal muscle fiber does not vary much. Each fiber can exert a force on the order of 0.3 micronewton. By this definition, the strongest muscle of the body is usually said to be the quadriceps femoris or the gluteus maximus.

- Because muscle strength is determined by cross-sectional area, a shorter muscle will be stronger "pound for pound" (i.e., by weight) than a longer muscle of the same cross-sectional area. The myometrial layer of the uterus may be the strongest muscle by weight in the female human body. At the time when an infant is delivered, the entire human uterus weighs about 1.1 kg (40 oz). During childbirth, the uterus exerts 100 to 400 N (25 to 100 lbf) of downward force with each contraction.

- The external muscles of the eye are conspicuously large and strong in relation to the small size and weight of the eyeball. It is frequently said that they are "the strongest muscles for the job they have to do" and are sometimes claimed to be "100 times stronger than they need to be." However, eye movements (particularly saccades used on facial scanning and reading) do require high speed movements, and eye muscles are exercised nightly during rapid eye movement sleep.

- The statement that "the tongue is the strongest muscle in the body" appears frequently in lists of surprising facts, but it is difficult to find any definition of "strength" that would make this statement true. Note that the tongue consists of eight muscles, not one.

- The heart has a claim to being the muscle that performs the largest quantity of physical work in the course of a lifetime. Estimates of the power output of the human heart range from 1 to 5 watts. This is much less than the maximum power output of other muscles; for example, the quadriceps can produce over 100 watts, but only for a few minutes. The heart does its work continuously over an entire lifetime without pause, and thus does "outwork" other muscles. An output of one watt continuously for eighty years yields a total work output of two and a half gigajoules.

Exercise

Main article: Physical exercise

Exercise is often recommended as a means of improving motor skills, fitness, muscle and bone strength, and joint function. Exercise has several effects upon muscles, connective tissue, bone, and the nerves that stimulate the muscles. One such effect is muscle hypertrophy, an increase in size of muscle due to an increase in the number of muscle fibers or cross-sectional area of myofibrils. The degree of hypertrophy and other exercise induced changes in muscle depends on the intensity and duration of exercise.

Generally, there are two types of exercise regimes, aerobic and anaerobic. Aerobic exercise (e.g. marathons) involves low intensity, but long duration activities during which, the muscles used are below their maximal contraction strength. Aerobic activities rely on the aerobic respiration (i.e. citric acid cycle and electron transport chain) for metabolic energy by consuming fat, protein carbohydrates, and oxygen. Muscles involved in aerobic exercises contain a higher percentage of Type I (or slow-twitch) muscle fibers, which primarily contain mitochondrial and oxidation enzymes associated with aerobic respiration. On the contrary, anaerobic exercise is associated with short duration, but high intensity exercise (e.g. sprinting and weight lifting). The anaerobic activities predominately use Type II, fast-twitch, muscle fibers. Type II muscle fibers rely on glucogenesis for energy during anaerobic exercise. During anaerobic exercise, type II fibers consume little oxygen, protein and fat, produces large amounts of lactic acid and are fatigable. Many exercises are partially aerobic and anaerobic; for example, soccer and rock climbing.

The presence of lactic acid has an inhibitory effect on ATP generation within the muscle. It can even stop ATP production if the intracellular concentration becomes too high. However, endurance training mitigates the buildup of lactic acid through increased capillarization and myoglobin. This increases the ability to remove waste products, like lactic acid, out of the muscles in order to not impair muscle function. Once moved out of muscles, lactic acid can be used by other muscles or body tissues as a source of energy, or transported to the liver where it is converted back to pyruvate. In addition to increasing the level of lactic acid, strenuous exercise results in the loss of potassium ions in muscle. This may facilitate the recovery of muscle function by protecting against fatigue .

Delayed onset muscle soreness is pain or discomfort that may be felt one to three days after exercising and generally subsides two to three days after which. Once thought to be caused by lactic acid build-up, a more recent theory is that it is caused by tiny tears in the muscle fibers caused by eccentric contraction, or unaccustomed training levels. Since lactic acid disperses fairly rapidly, it could not explain pain experienced days after exercise.

Clinical significance

Hypertrophy

Main article: Muscle hypertrophyIndependent of strength and performance measures, muscles can be induced to grow larger by a number of factors, including hormone signaling, developmental factors, strength training, and disease. Contrary to popular belief, the number of muscle fibres cannot be increased through exercise. Instead, muscles grow larger through a combination of muscle cell growth as new protein filaments are added along with additional mass provided by undifferentiated satellite cells alongside the existing muscle cells.

Biological factors such as age and hormone levels can affect muscle hypertrophy. During puberty in males, hypertrophy occurs at an accelerated rate as the levels of growth-stimulating hormones produced by the body increase. Natural hypertrophy normally stops at full growth in the late teens. As testosterone is one of the body's major growth hormones, on average, men find hypertrophy much easier to achieve than women. Taking additional testosterone or other anabolic steroids will increase muscular hypertrophy.

Muscular, spinal and neural factors all affect muscle building. Sometimes a person may notice an increase in strength in a given muscle even though only its opposite has been subject to exercise, such as when a bodybuilder finds her left biceps stronger after completing a regimen focusing only on the right biceps. This phenomenon is called cross education.

Atrophy

Main article: Muscle atrophy

During ordinary living activities, between 1 and 2 percent of muscle is broken down and rebuilt daily. Inactivity and starvation in mammals lead to atrophy of skeletal muscle, a decrease in muscle mass that may be accompanied by a smaller number and size of the muscle cells as well as lower protein content. Muscle atrophy may also result from the natural aging process or from disease.

In humans, prolonged periods of immobilization, as in the cases of bed rest or astronauts flying in space, are known to result in muscle weakening and atrophy. Atrophy is of particular interest to the manned spaceflight community, because the weightlessness experienced in spaceflight results is a loss of as much as 30% of mass in some muscles. Such consequences are also noted in small hibernating mammals like the golden-mantled ground squirrels and brown bats.

During aging, there is a gradual decrease in the ability to maintain skeletal muscle function and mass, known as sarcopenia. The exact cause of sarcopenia is unknown, but it may be due to a combination of the gradual failure in the "satellite cells" that help to regenerate skeletal muscle fibers, and a decrease in sensitivity to or the availability of critical secreted growth factors that are necessary to maintain muscle mass and satellite cell survival. Sarcopenia is a normal aspect of aging, and is not actually a disease state yet can be linked to many injuries in the elderly population as well as decreasing quality of life.

There are also many diseases and conditions that cause muscle atrophy. Examples include cancer and AIDS, which induce a body wasting syndrome called cachexia. Other syndromes or conditions that can induce skeletal muscle atrophy are congestive heart disease and some diseases of the liver.

Disease

Main article: Neuromuscular disease

Neuromuscular diseases are those that affect the muscles and/or their nervous control. In general, problems with nervous control can cause spasticity or paralysis, depending on the location and nature of the problem. A large proportion of neurological disorders, ranging from cerebrovascular accident (stroke) and Parkinson's disease to Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, can lead to problems with movement or motor coordination.

Symptoms of muscle diseases may include weakness, spasticity, myoclonus and myalgia. Diagnostic procedures that may reveal muscular disorders include testing creatine kinase levels in the blood and electromyography (measuring electrical activity in muscles). In some cases, muscle biopsy may be done to identify a myopathy, as well as genetic testing to identify DNA abnormalities associated with specific myopathies and dystrophies.

A non-invasive elastography technique that measures muscle noise is undergoing experimentation to provide a way of monitoring neuromuscular disease. The sound produced by a muscle comes from the shortening of actomyosin filaments along the axis of the muscle. During contraction, the muscle shortens along its longitudinal axis and expands across the transverse axis, producing vibrations at the surface.

See also

- Electroactive polymers – materials that behave like muscles, used in robotics research

- Hand strength

- Meat

- Muscle memory

- Myotomy

- Preflexes

- Rohmert's law – pertaining to muscle fatigue

References

- "Welcome to CK-12 Foundation | CK-12 Foundation". www.ck12.org.

- Mackenzie, Colin (1918). The Action of Muscles: Including Muscle Rest and Muscle Re-education. England: Paul B. Hoeber. p. 1. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Brainard, Jean; Gray-Wilson, Niamh; Harwood, Jessica; Karasov, Corliss; Kraus, Dors; Willan, Jane (2011). CK-12 Life Science Honors for Middle School. CK-12 Foundation. p. 451. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Alfred Carey Carpenter (2007). "Muscle". Anatomy Words. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Douglas Harper (2012). "Muscle". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Marieb, EN; Hoehn, Katja (2010). Human Anatomy & Physiology (8th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-8053-9569-3.

- ^ McCloud, Aaron (30 November 2011). "Build Fast Twitch Muscle Fibers". Complete Strength Training. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Larsson, L; Edström, L; Lindegren, B; Gorza, L; Schiaffino, S (July 1991). "MHC composition and enzyme-histochemical and physiological properties of a novel fast-twitch motor unit type". The American Journal of Physiology. 261 (1 pt 1): C93–101. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.1.C93. PMID 1858863.

- Hoyle, Graham (1983). "8. Muscle Cell Diversity". Muscles and Their Neural Control. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 293–299. ISBN 9780471877097.

- Anderson, M; Finlayson, L. H. (1976). "The effect of exercise on the growth of mitochondria and myofibrils in the flight muscles of the Tsetse fly, Glossina morsitans". J. Morph. 150 (2): 321–326. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051500205. S2CID 85719905.

- MacIntosh, BR; Gardiner, PF; McComas, AJ (2006). "1. Muscle Architecture and Muscle Fiber Anatomy". Skeletal Muscle: Form and Function (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-0-7360-4517-9.

- Kent, George C (1987). "11. Muscles". Comparative Anatomy of the Vertebrates (7th ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers. pp. 326–374. ISBN 978-0-697-23486-5.

- ^ Poole, RM, ed. (1986). The Incredible Machine. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. pp. 307–311. ISBN 978-0-87044-621-4.

- ^ Sweeney, Lauren (1997). Basic Concepts in Embryology: A Student's Survival Guide (1st Paperback ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional.

- Kardong, Kenneth (2015). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution. New York: McGraw Hill Education. pp. 374–377. ISBN 978-1-259-25375-1.

- Heymsfield, SB; Gallagher, D; Kotler, DP; Wang, Z; Allison, DB; Heshka, S (2002). "Body-size dependence of resting energy expenditure can be attributed to nonenergetic homogeneity of fat-free mass". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 282 (1): E132 – E138. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.2002.282.1.e132. PMID 11739093.

- "Concept II Rowing Ergometer, user manual" (PDF). 1993. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2010.

- McGinnis, Peter M. (2013). Biomechanics of Sport and Exercise (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. ISBN 978-0-7360-7966-2.

- Muslumova, Irada (2003). "Power of a Human Heart". The Physics Factbook.

- Gonyea WJ, Sale DG, Gonyea FB, Mikesky A (1986). "Exercise induced increases in muscle fiber number". Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 55 (2): 137–41. doi:10.1007/BF00714995. PMID 3698999. S2CID 29191826.

- Jansson E, Kaijser L (July 1977). "Muscle adaptation to extreme endurance training in man". Acta Physiol. Scand. 100 (3): 315–24. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb05956.x. PMID 144412.

- Gollnick PD, Armstrong RB, Saubert CW, Piehl K, Saltin B (September 1972). "Enzyme activity and fiber composition in skeletal muscle of untrained and trained men". J Appl Physiol. 33 (3): 312–9. doi:10.1152/jappl.1972.33.3.312. PMID 4403464.

- Schantz P, Henriksson J, Jansson E (April 1983). "Adaptation of human skeletal muscle to endurance training of long duration". Clin Physiol. 3 (2): 141–51. doi:10.1111/j.1475-097x.1983.tb00685.x. PMID 6682735.

- Monster AW, Chan H, O'Connor D (April 1978). "Activity patterns of human skeletal muscles: relation to muscle fiber type composition". Science. 200 (4339): 314–7. doi:10.1126/science.635587. PMID 635587.

- Pattengale PK, Holloszy JO (September 1967). "Augmentation of skeletal muscle myoglobin by a program of treadmill running". Am. J. Physiol. 213 (3): 783–5. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.213.3.783. PMID 6036801.

- Nielsen, OB; Paoli, F; Overgaard, K (2001). "Protective effects of lactic acid on force production in rat skeletal muscle". Journal of Physiology. 536 (1): 161–166. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00161.x. PMC 2278832. PMID 11579166.

- Robergs, R; Ghiasvand, F; Parker, D (2004). "Biochemistry of exercise-induced metabolic acidosis". Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 287 (3): R502–516. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00114.2004. PMID 15308499.

- Fuster, G; Busquets, S; Almendro, V; López-Soriano, FJ; Argilés, JM (2007). "Antiproteolytic effects of plasma from hibernating bears: a new approach for muscle wasting therapy?". Clin Nutr. 26 (5): 658–661. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2007.07.003. PMID 17904252.

- Roy, RR; Baldwin, KM; Edgerton, VR (1996). "Response of the neuromuscular unit to spaceflight: What has been learned from the rat model". Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 24: 399–425. doi:10.1249/00003677-199600240-00015. PMID 8744257. S2CID 44574997.

- "NASA Muscle Atrophy Research (MARES) Website". Archived from the original on 4 May 2010.

- Lohuis, TD; Harlow, HJ; Beck, TD (2007). "Hibernating black bears (Ursus americanus) experience skeletal muscle protein balance during winter anorexia". Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B, Biochem. Mol. Biol. 147 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.12.020. PMID 17307375.

- Roche, Alex F. (1994). "Sarcopenia: A critical review of its measurements and health-related significance in the middle-aged and elderly". American Journal of Human Biology. 6 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1002/ajhb.1310060107. PMID 28548430. S2CID 7301230.

- Dumé, Belle (18 May 2007). "'Muscle noise' could reveal diseases' progression". NewScientist.com news service.

External links

Media related to muscles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to muscles at Wikimedia Commons- University of Dundee article on performing neurological examinations (Quadriceps "strongest")

- Muscle efficiency in rowing

- Muscle Physiology and Modeling Scholarpedia Tsianos and Loeb (2013)

- Human Muscle Tutorial (clear pictures of main human muscles and their Latin names, good for orientation)

- Microscopic stains of skeletal and cardiac muscular fibers to show striations. Note the differences in myofibrilar arrangements.

| Biological tissues | |

|---|---|

| Animals | |

| Plants | |

| Muscular system | |

|---|---|

| Tissue | |

| Shape | |

| Other | |

| Muscle tissue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smooth muscle | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Striated muscle |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muscles of the head | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraocular |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Masticatory |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Facial |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Soft palate |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Tongue |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Muscles of the neck | |

|---|---|

| Cervical | |

| Suboccipital | |

| Suprahyoid | |

| Infrahyoid | |

| Pharynx | |

| Larynx | |

| Trachea | |

| Fasciae | |

| Muscles of the thorax and back | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back |

| ||||||||||

| Thorax |

| ||||||||||

| Muscles and ligaments of abdomen and pelvis | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal wall |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pelvis |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Muscles of the arm | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Arm (compartments) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Forearm (compartments) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Hand |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Muscles of the hip and human leg | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iliac region | |||||||||||||||||

| Buttocks |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Thigh / compartments |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Leg/ compartments |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Foot |

| ||||||||||||||||