| Part of a series of articles about | ||||||

| Calculus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Differential

|

||||||

Integral

|

||||||

Series

|

||||||

Vector

|

||||||

Multivariable

|

||||||

|

Advanced |

||||||

| Specialized | ||||||

| Miscellanea | ||||||

In vector calculus, the curl, also known as rotor, is a vector operator that describes the infinitesimal circulation of a vector field in three-dimensional Euclidean space. The curl at a point in the field is represented by a vector whose length and direction denote the magnitude and axis of the maximum circulation. The curl of a field is formally defined as the circulation density at each point of the field.

A vector field whose curl is zero is called irrotational. The curl is a form of differentiation for vector fields. The corresponding form of the fundamental theorem of calculus is Stokes' theorem, which relates the surface integral of the curl of a vector field to the line integral of the vector field around the boundary curve.

The notation curl F is more common in North America. In the rest of the world, particularly in 20th century scientific literature, the alternative notation rot F is traditionally used, which comes from the "rate of rotation" that it represents. To avoid confusion, modern authors tend to use the cross product notation with the del (nabla) operator, as in , which also reveals the relation between curl (rotor), divergence, and gradient operators.

Unlike the gradient and divergence, curl as formulated in vector calculus does not generalize simply to other dimensions; some generalizations are possible, but only in three dimensions is the geometrically defined curl of a vector field again a vector field. This deficiency is a direct consequence of the limitations of vector calculus; on the other hand, when expressed as an antisymmetric tensor field via the wedge operator of geometric calculus, the curl generalizes to all dimensions. The circumstance is similar to that attending the 3-dimensional cross product, and indeed the connection is reflected in the notation for the curl.

The name "curl" was first suggested by James Clerk Maxwell in 1871 but the concept was apparently first used in the construction of an optical field theory by James MacCullagh in 1839.

Definition

The components of F at position r, normal and tangent to a closed curve C in a plane, enclosing a planar vector area .

Right-hand rule

The components of F at position r, normal and tangent to a closed curve C in a plane, enclosing a planar vector area .

Right-hand rule Convention for vector orientation of the line integral

Convention for vector orientation of the line integral The thumb points in the direction of and the fingers curl along the orientation of C

The thumb points in the direction of and the fingers curl along the orientation of C

The curl of a vector field F, denoted by curl F, or , or rot F, is an operator that maps C functions in R to C functions in R, and in particular, it maps continuously differentiable functions R → R to continuous functions R → R. It can be defined in several ways, to be mentioned below:

One way to define the curl of a vector field at a point is implicitly through its components along various axes passing through the point: if is any unit vector, the component of the curl of F along the direction may be defined to be the limiting value of a closed line integral in a plane perpendicular to divided by the area enclosed, as the path of integration is contracted indefinitely around the point.

More specifically, the curl is defined at a point p as where the line integral is calculated along the boundary C of the area A in question, |A| being the magnitude of the area. This equation defines the component of the curl of F along the direction . The infinitesimal surfaces bounded by C have as their normal. C is oriented via the right-hand rule.

The above formula means that the component of the curl of a vector field along a certain axis is the infinitesimal area density of the circulation of the field in a plane perpendicular to that axis. This formula does not a priori define a legitimate vector field, for the individual circulation densities with respect to various axes a priori need not relate to each other in the same way as the components of a vector do; that they do indeed relate to each other in this precise manner must be proven separately.

To this definition fits naturally the Kelvin–Stokes theorem, as a global formula corresponding to the definition. It equates the surface integral of the curl of a vector field to the above line integral taken around the boundary of the surface.

Another way one can define the curl vector of a function F at a point is explicitly as the limiting value of a vector-valued surface integral around a shell enclosing p divided by the volume enclosed, as the shell is contracted indefinitely around p.

More specifically, the curl may be defined by the vector formula where the surface integral is calculated along the boundary S of the volume V, |V| being the magnitude of the volume, and pointing outward from the surface S perpendicularly at every point in S.

In this formula, the cross product in the integrand measures the tangential component of F at each point on the surface S, and points along the surface at right angles to the tangential projection of F. Integrating this cross product over the whole surface results in a vector whose magnitude measures the overall circulation of F around S, and whose direction is at right angles to this circulation. The above formula says that the curl of a vector field at a point is the infinitesimal volume density of this "circulation vector" around the point.

To this definition fits naturally another global formula (similar to the Kelvin-Stokes theorem) which equates the volume integral of the curl of a vector field to the above surface integral taken over the boundary of the volume.

Whereas the above two definitions of the curl are coordinate free, there is another "easy to memorize" definition of the curl in curvilinear orthogonal coordinates, e.g. in Cartesian coordinates, spherical, cylindrical, or even elliptical or parabolic coordinates:

The equation for each component (curl F)k can be obtained by exchanging each occurrence of a subscript 1, 2, 3 in cyclic permutation: 1 → 2, 2 → 3, and 3 → 1 (where the subscripts represent the relevant indices).

If (x1, x2, x3) are the Cartesian coordinates and (u1, u2, u3) are the orthogonal coordinates, then is the length of the coordinate vector corresponding to ui. The remaining two components of curl result from cyclic permutation of indices: 3,1,2 → 1,2,3 → 2,3,1.

Usage

In practice, the two coordinate-free definitions described above are rarely used because in virtually all cases, the curl operator can be applied using some set of curvilinear coordinates, for which simpler representations have been derived.

The notation has its origins in the similarities to the 3-dimensional cross product, and it is useful as a mnemonic in Cartesian coordinates if is taken as a vector differential operator del. Such notation involving operators is common in physics and algebra.

Expanded in 3-dimensional Cartesian coordinates (see Del in cylindrical and spherical coordinates for spherical and cylindrical coordinate representations), is, for composed of (where the subscripts indicate the components of the vector, not partial derivatives): where i, j, and k are the unit vectors for the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively. This expands as follows:

Although expressed in terms of coordinates, the result is invariant under proper rotations of the coordinate axes but the result inverts under reflection.

In a general coordinate system, the curl is given by where ε denotes the Levi-Civita tensor, ∇ the covariant derivative, is the determinant of the metric tensor and the Einstein summation convention implies that repeated indices are summed over. Due to the symmetry of the Christoffel symbols participating in the covariant derivative, this expression reduces to the partial derivative: where Rk are the local basis vectors. Equivalently, using the exterior derivative, the curl can be expressed as:

Here ♭ and ♯ are the musical isomorphisms, and ★ is the Hodge star operator. This formula shows how to calculate the curl of F in any coordinate system, and how to extend the curl to any oriented three-dimensional Riemannian manifold. Since this depends on a choice of orientation, curl is a chiral operation. In other words, if the orientation is reversed, then the direction of the curl is also reversed.

Examples

Example 1

Suppose the vector field describes the velocity field of a fluid flow (such as a large tank of liquid or gas) and a small ball is located within the fluid or gas (the center of the ball being fixed at a certain point). If the ball has a rough surface, the fluid flowing past it will make it rotate. The rotation axis (oriented according to the right hand rule) points in the direction of the curl of the field at the center of the ball, and the angular speed of the rotation is half the magnitude of the curl at this point. The curl of the vector field at any point is given by the rotation of an infinitesimal area in the xy-plane (for z-axis component of the curl), zx-plane (for y-axis component of the curl) and yz-plane (for x-axis component of the curl vector). This can be seen in the examples below.

Example 2

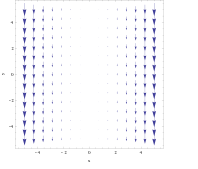

Vector field F(x,y)= (left) and its curl (right).

Vector field F(x,y)= (left) and its curl (right).

The vector field can be decomposed as

Upon visual inspection, the field can be described as "rotating". If the vectors of the field were to represent a linear force acting on objects present at that point, and an object were to be placed inside the field, the object would start to rotate clockwise around itself. This is true regardless of where the object is placed.

Calculating the curl:

The resulting vector field describing the curl would at all points be pointing in the negative z direction. The results of this equation align with what could have been predicted using the right-hand rule using a right-handed coordinate system. Being a uniform vector field, the object described before would have the same rotational intensity regardless of where it was placed.

Example 3

Vector field F(x, y) = (left) and its curl (right).

Vector field F(x, y) = (left) and its curl (right).

For the vector field

the curl is not as obvious from the graph. However, taking the object in the previous example, and placing it anywhere on the line x = 3, the force exerted on the right side would be slightly greater than the force exerted on the left, causing it to rotate clockwise. Using the right-hand rule, it can be predicted that the resulting curl would be straight in the negative z direction. Inversely, if placed on x = −3, the object would rotate counterclockwise and the right-hand rule would result in a positive z direction.

Calculating the curl:

The curl points in the negative z direction when x is positive and vice versa. In this field, the intensity of rotation would be greater as the object moves away from the plane x = 0.

Further examples

- In a vector field describing the linear velocities of each part of a rotating disk in uniform circular motion, the curl has the same value at all points, and this value turns out to be exactly two times the vectorial angular velocity of the disk (oriented as usual by the right-hand rule). More generally, for any flowing mass, the linear velocity vector field at each point of the mass flow has a curl (the vorticity of the flow at that point) equal to exactly two times the local vectorial angular velocity of the mass about the point.

- For any solid object subject to an external physical force (such as gravity or the electromagnetic force), one may consider the vector field representing the infinitesimal force-per-unit-volume contributions acting at each of the points of the object. This force field may create a net torque on the object about its center of mass, and this torque turns out to be directly proportional and vectorially parallel to the (vector-valued) integral of the curl of the force field over the whole volume.

- Of the four Maxwell's equations, two—Faraday's law and Ampère's law—can be compactly expressed using curl. Faraday's law states that the curl of an electric field is equal to the opposite of the time rate of change of the magnetic field, while Ampère's law relates the curl of the magnetic field to the current and the time rate of change of the electric field.

Identities

Main article: Vector calculus identitiesIn general curvilinear coordinates (not only in Cartesian coordinates), the curl of a cross product of vector fields v and F can be shown to be

Interchanging the vector field v and ∇ operator, we arrive at the cross product of a vector field with curl of a vector field: where ∇F is the Feynman subscript notation, which considers only the variation due to the vector field F (i.e., in this case, v is treated as being constant in space).

Another example is the curl of a curl of a vector field. It can be shown that in general coordinates and this identity defines the vector Laplacian of F, symbolized as ∇F.

The curl of the gradient of any scalar field φ is always the zero vector field which follows from the antisymmetry in the definition of the curl, and the symmetry of second derivatives.

The divergence of the curl of any vector field is equal to zero:

If φ is a scalar valued function and F is a vector field, then

Generalizations

The vector calculus operations of grad, curl, and div are most easily generalized in the context of differential forms, which involves a number of steps. In short, they correspond to the derivatives of 0-forms, 1-forms, and 2-forms, respectively. The geometric interpretation of curl as rotation corresponds to identifying bivectors (2-vectors) in 3 dimensions with the special orthogonal Lie algebra of infinitesimal rotations (in coordinates, skew-symmetric 3 × 3 matrices), while representing rotations by vectors corresponds to identifying 1-vectors (equivalently, 2-vectors) and , these all being 3-dimensional spaces.

Differential forms

Main article: Differential formIn 3 dimensions, a differential 0-form is a real-valued function ; a differential 1-form is the following expression, where the coefficients are functions: a differential 2-form is the formal sum, again with function coefficients: and a differential 3-form is defined by a single term with one function as coefficient: (Here the a-coefficients are real functions of three variables; the "wedge products", e.g. , can be interpreted as some kind of oriented area elements, , etc.)

The exterior derivative of a k-form in R is defined as the (k + 1)-form from above—and in R if, e.g., then the exterior derivative d leads to

The exterior derivative of a 1-form is therefore a 2-form, and that of a 2-form is a 3-form. On the other hand, because of the interchangeability of mixed derivatives, and antisymmetry,

the twofold application of the exterior derivative yields (the zero -form).

Thus, denoting the space of k-forms by and the exterior derivative by d one gets a sequence:

Here is the space of sections of the exterior algebra vector bundle over R, whose dimension is the binomial coefficient ; note that for or . Writing only dimensions, one obtains a row of Pascal's triangle:

the 1-dimensional fibers correspond to scalar fields, and the 3-dimensional fibers to vector fields, as described below. Modulo suitable identifications, the three nontrivial occurrences of the exterior derivative correspond to grad, curl, and div.

Differential forms and the differential can be defined on any Euclidean space, or indeed any manifold, without any notion of a Riemannian metric. On a Riemannian manifold, or more generally pseudo-Riemannian manifold, k-forms can be identified with k-vector fields (k-forms are k-covector fields, and a pseudo-Riemannian metric gives an isomorphism between vectors and covectors), and on an oriented vector space with a nondegenerate form (an isomorphism between vectors and covectors), there is an isomorphism between k-vectors and (n − k)-vectors; in particular on (the tangent space of) an oriented pseudo-Riemannian manifold. Thus on an oriented pseudo-Riemannian manifold, one can interchange k-forms, k-vector fields, (n − k)-forms, and (n − k)-vector fields; this is known as Hodge duality. Concretely, on R this is given by:

- 1-forms and 1-vector fields: the 1-form ax dx + ay dy + az dz corresponds to the vector field (ax, ay, az).

- 1-forms and 2-forms: one replaces dx by the dual quantity dy ∧ dz (i.e., omit dx), and likewise, taking care of orientation: dy corresponds to dz ∧ dx = −dx ∧ dz, and dz corresponds to dx ∧ dy. Thus the form ax dx + ay dy + az dz corresponds to the "dual form" az dx ∧ dy + ay dz ∧ dx + ax dy ∧ dz.

Thus, identifying 0-forms and 3-forms with scalar fields, and 1-forms and 2-forms with vector fields:

- grad takes a scalar field (0-form) to a vector field (1-form);

- curl takes a vector field (1-form) to a pseudovector field (2-form);

- div takes a pseudovector field (2-form) to a pseudoscalar field (3-form)

On the other hand, the fact that d = 0 corresponds to the identities for any scalar field f, and for any vector field v.

Grad and div generalize to all oriented pseudo-Riemannian manifolds, with the same geometric interpretation, because the spaces of 0-forms and n-forms at each point are always 1-dimensional and can be identified with scalar fields, while the spaces of 1-forms and (n − 1)-forms are always fiberwise n-dimensional and can be identified with vector fields.

Curl does not generalize in this way to 4 or more dimensions (or down to 2 or fewer dimensions); in 4 dimensions the dimensions are

0 → 1 → 4 → 6 → 4 → 1 → 0;so the curl of a 1-vector field (fiberwise 4-dimensional) is a 2-vector field, which at each point belongs to 6-dimensional vector space, and so one has which yields a sum of six independent terms, and cannot be identified with a 1-vector field. Nor can one meaningfully go from a 1-vector field to a 2-vector field to a 3-vector field (4 → 6 → 4), as taking the differential twice yields zero (d = 0). Thus there is no curl function from vector fields to vector fields in other dimensions arising in this way.

However, one can define a curl of a vector field as a 2-vector field in general, as described below.

Curl geometrically

2-vectors correspond to the exterior power ΛV; in the presence of an inner product, in coordinates these are the skew-symmetric matrices, which are geometrically considered as the special orthogonal Lie algebra (V) of infinitesimal rotations. This has (

2) = 1/2n(n − 1) dimensions, and allows one to interpret the differential of a 1-vector field as its infinitesimal rotations. Only in 3 dimensions (or trivially in 0 dimensions) we have n = 1/2n(n − 1), which is the most elegant and common case. In 2 dimensions the curl of a vector field is not a vector field but a function, as 2-dimensional rotations are given by an angle (a scalar – an orientation is required to choose whether one counts clockwise or counterclockwise rotations as positive); this is not the div, but is rather perpendicular to it. In 3 dimensions the curl of a vector field is a vector field as is familiar (in 1 and 0 dimensions the curl of a vector field is 0, because there are no non-trivial 2-vectors), while in 4 dimensions the curl of a vector field is, geometrically, at each point an element of the 6-dimensional Lie algebra .

The curl of a 3-dimensional vector field which only depends on 2 coordinates (say x and y) is simply a vertical vector field (in the z direction) whose magnitude is the curl of the 2-dimensional vector field, as in the examples on this page.

Considering curl as a 2-vector field (an antisymmetric 2-tensor) has been used to generalize vector calculus and associated physics to higher dimensions.

Inverse

Main article: Helmholtz decompositionIn the case where the divergence of a vector field V is zero, a vector field W exists such that V = curl(W). This is why the magnetic field, characterized by zero divergence, can be expressed as the curl of a magnetic vector potential.

If W is a vector field with curl(W) = V, then adding any gradient vector field grad(f) to W will result in another vector field W + grad(f) such that curl(W + grad(f)) = V as well. This can be summarized by saying that the inverse curl of a three-dimensional vector field can be obtained up to an unknown irrotational field with the Biot–Savart law.

See also

- Helmholtz decomposition

- Hiptmair–Xu preconditioner

- Del in cylindrical and spherical coordinates

- Vorticity

References

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Curl". MathWorld.

- ISO/IEC 80000-2 standard Norm ISO/IEC 80000-2, item 2-17.16

- Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, March 9th, 1871

- Collected works of James MacCullagh. Dublin: Hodges. 1880.

- Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics tripod.com

- Mathematical methods for physics and engineering, K.F. Riley, M.P. Hobson, S.J. Bence, Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-86153-3

- Vector Analysis (2nd Edition), M.R. Spiegel, S. Lipschutz, D. Spellman, Schaum's Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 2009, ISBN 978-0-07-161545-7

- Arfken, George Brown (2005). Mathematical methods for physicists. Weber, Hans-Jurgen (6th ed.). Boston: Elsevier. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-08-047069-6. OCLC 127114279.

- Gibbs, Josiah Willard; Wilson, Edwin Bidwell (1901), Vector analysis, Yale bicentennial publications, C. Scribner's Sons, hdl:2027/mdp.39015000962285

- McDavid, A. W.; McMullen, C. D. (2006-10-30). "Generalizing Cross Products and Maxwell's Equations to Universal Extra Dimensions". arXiv:hep-ph/0609260.

Further reading

- Korn, Granino Arthur and Theresa M. Korn (January 2000). Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers: Definitions, Theorems, and Formulas for Reference and Review. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 157–160. ISBN 0-486-41147-8.

- Schey, H. M. (1997). Div, Grad, Curl, and All That: An Informal Text on Vector Calculus. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-96997-5.

External links

- "Curl", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- "Multivariable calculus". mathinsight.org. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- "Divergence and Curl: The Language of Maxwell's Equations, Fluid Flow, and More". June 21, 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-11-24 – via YouTube.

| Calculus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precalculus | |||||

| Limits | |||||

| Differential calculus |

| ||||

| Integral calculus | |||||

| Vector calculus |

| ||||

| Multivariable calculus | |||||

| Sequences and series |

| ||||

| Special functions and numbers | |||||

| History of calculus | |||||

| Lists |

| ||||

| Miscellaneous topics |

| ||||

, which also reveals the relation between curl (rotor),

, which also reveals the relation between curl (rotor),  for the curl.

for the curl.

.

Right-hand rule

.

Right-hand rule and the fingers curl along the orientation of C

and the fingers curl along the orientation of C

is any unit vector, the component of the curl of F along the direction

is any unit vector, the component of the curl of F along the direction  where the

where the  where the surface integral is calculated along the boundary S of the volume V, |V| being the magnitude of the volume, and

where the surface integral is calculated along the boundary S of the volume V, |V| being the magnitude of the volume, and

is the length of the coordinate vector corresponding to ui. The remaining two components of curl result from

is the length of the coordinate vector corresponding to ui. The remaining two components of curl result from  is taken as a vector

is taken as a vector  composed of

composed of  (where the subscripts indicate the components of the vector, not partial derivatives):

(where the subscripts indicate the components of the vector, not partial derivatives):

where i, j, and k are the

where i, j, and k are the

where ε denotes the

where ε denotes the  is the

is the  where Rk are the local basis vectors. Equivalently, using the

where Rk are the local basis vectors. Equivalently, using the

can be decomposed as

can be decomposed as

where ∇F is the Feynman subscript notation, which considers only the variation due to the vector field F (i.e., in this case, v is treated as being constant in space).

where ∇F is the Feynman subscript notation, which considers only the variation due to the vector field F (i.e., in this case, v is treated as being constant in space).

and this identity defines the

and this identity defines the  which follows from the

which follows from the

of infinitesimal rotations (in coordinates, skew-symmetric 3 × 3 matrices), while representing rotations by vectors corresponds to identifying 1-vectors (equivalently, 2-vectors) and

of infinitesimal rotations (in coordinates, skew-symmetric 3 × 3 matrices), while representing rotations by vectors corresponds to identifying 1-vectors (equivalently, 2-vectors) and  ; a differential 1-form is the following expression, where the coefficients are functions:

; a differential 1-form is the following expression, where the coefficients are functions:

a differential 2-form is the formal sum, again with function coefficients:

a differential 2-form is the formal sum, again with function coefficients:

and a differential 3-form is defined by a single term with one function as coefficient:

and a differential 3-form is defined by a single term with one function as coefficient:

(Here the a-coefficients are real functions of three variables; the "wedge products", e.g.

(Here the a-coefficients are real functions of three variables; the "wedge products", e.g.  , can be interpreted as some kind of oriented area elements,

, can be interpreted as some kind of oriented area elements,  , etc.)

, etc.)

then the exterior derivative d leads to

then the exterior derivative d leads to

and antisymmetry,

and antisymmetry,

(the zero

(the zero  -form).

-form).

and the exterior derivative by d one gets a sequence:

and the exterior derivative by d one gets a sequence:

is the space of sections of the

is the space of sections of the

; note that

; note that  for

for  or

or  . Writing only dimensions, one obtains a row of

. Writing only dimensions, one obtains a row of

for any scalar field f, and

for any scalar field f, and

for any vector field v.

for any vector field v.

which yields a sum of six independent terms, and cannot be identified with a 1-vector field. Nor can one meaningfully go from a 1-vector field to a 2-vector field to a 3-vector field (4 → 6 → 4), as taking the differential twice yields zero (d = 0). Thus there is no curl function from vector fields to vector fields in other dimensions arising in this way.

which yields a sum of six independent terms, and cannot be identified with a 1-vector field. Nor can one meaningfully go from a 1-vector field to a 2-vector field to a 3-vector field (4 → 6 → 4), as taking the differential twice yields zero (d = 0). Thus there is no curl function from vector fields to vector fields in other dimensions arising in this way.

(V) of infinitesimal rotations. This has (

(V) of infinitesimal rotations. This has ( .

.