| Revision as of 17:53, 28 June 2014 edit92.80.169.28 (talk) →Pharmacokinetics← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:59, 30 June 2014 edit undoDavid Hedlund (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,269 edits Adding "alcohol (drug)" in medicine-related contextNext edit → | ||

| Line 187: | Line 187: | ||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| Phenobarbital is sometimes indicated for alcohol and benzodiazepine detoxification for its sedative and anticonvulsant properties. The benzodiazepines ] (Librium) and ] (Serax) have largely replaced phenobarbital for detoxification.<ref>http://www.aafp.org/afp/980700ap/miller.html</ref> | Phenobarbital is sometimes indicated for ] and benzodiazepine detoxification for its sedative and anticonvulsant properties. The benzodiazepines ] (Librium) and ] (Serax) have largely replaced phenobarbital for detoxification.<ref>http://www.aafp.org/afp/980700ap/miller.html</ref> | ||

| ===Other uses=== | ===Other uses=== | ||

Revision as of 16:59, 30 June 2014

Not to be confused with Pentobarbital. Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Luminal |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682007 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, rectal, parenteral (intramuscular and intravenous) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >95% |

| Protein binding | 20 to 45% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (mostly CYP2C19) |

| Elimination half-life | 53 to 118 hours |

| Excretion | Renal and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.007 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H12N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 232.235 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenobarbital (INN) is a long-acting barbiturate and the most widely used anticonvulsant worldwide, and the oldest still commonly used. It also has sedative and hypnotic properties, but as with other barbiturates, it has been superseded by the benzodiazepines for these indications. The World Health Organization recommends its use as first-line for partial and generalized tonic–clonic seizures (those formerly known as grand mal) in developing countries. It is a core medicine in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, which is a list of minimum medical needs for a basic health care system. In more affluent countries, it is no longer recommended as a first- or second-line choice anticonvulsant for most seizure types, though it is still commonly used to treat neonatal seizures.

The injectable form is used principally to control status epilepticus, while the oral forms are used for prophylactic and maintenance therapy. Its very long active half-life means for some people doses do not have to be taken every day, particularly once the dose has been stabilized over a period of several weeks or months, and seizures are effectively controlled. It is occasionally still used as a sedative/hypnotic in anxious or agitated patients who may be intolerant of or do not have access to benzodiazepines, neuroleptics and other, newer drugs. For this purpose, phenobarbital has a lower dose range, but this practice is uncommon in developed countries.

Medical uses

Phenobarbital is used in the treatment of all types of seizures except absence seizures. It is no less effective at seizure control than more modern drugs such as phenytoin and carbamazepine. It is, however, significantly less well tolerated.

The first-line drugs for treatment of status epilepticus are fast-acting benzodiazepines, such as diazepam or lorazepam. If these fail, then phenytoin may be used, with phenobarbital being an alternative in the US, but used only third-line in the UK. Failing that, the only treatment is anaesthesia in intensive care.

Phenobarbital is the first-line choice for the treatment of neonatal seizures. Concerns that neonatal seizures in themselves could be harmful make most physicians treat them aggressively. No reliable evidence, though, supports this approach.

Phenobarbital is sometimes indicated for alcohol and benzodiazepine detoxification for its sedative and anticonvulsant properties. The benzodiazepines chlordiazepoxide (Librium) and oxazepam (Serax) have largely replaced phenobarbital for detoxification.

Other uses

Phenobarbital properties can effectively reduce tremors and seizures associated with abrupt withdrawal from benzodiazepines. Phenobarbital is a cytochrome P450 inducer, and is used to reduce the toxicity of some drugs.

Phenobarbital is occasionally prescribed in low doses to aid in the conjugation of bilirubin in people with Crigler-Najjar syndrome (Type II), or in patients suffering from Gilbert syndrome.

Phenobarbital can also be used to relieve cyclic vomiting syndrome symptoms.

In infants suspected of neonatal biliary atresia, phenobarbital is used in preparation for a Tc-IDA hepatobiliary study that differentiates atresia from hepatitis or chondrostasis.

Phenobarbital is used as a secondary agent to treat newborns with neonatal abstinence syndrome, a condition of withdrawal symptoms from exposure to opioid drugs in utero.

Side effects

Sedation and hypnosis are the principal side effects (occasionally, they are also the intended effects) of phenobarbital. Central nervous system effects, such as dizziness, nystagmus and ataxia, are also common. In elderly patients, it may cause excitement and confusion, while in children, it may result in paradoxical hyperactivity. Another very rare side effect is amelogenesis imperfecta.

Caution is to be used with children. Of anticonvulsant drugs, behavioural disturbances occur most frequently with clonazepam and phenobarbital.

Contraindications

Acute intermittent porphyria, oversensitivity for barbiturates, prior dependence on barbiturates, severe respiratory insufficiency and hyperkinesia in children are contraindications for phenobarbital use.

Mechanism of action

GABAA receptors are the primary target for barbiturates in the central nervous system. As is the case for other clinically important barbiturates, phenobarbital prolongs and potentiates the action of GABA on GABAA receptors and at higher concentrations directly activates the receptors. In contrast to anesthetic barbiturates such as pentobarbital, phenobarbital is minimally sedating at effective anticonvulsant doses. Possible explanations for the reduced sedative effect of phenobarbital include more regionally restricted action; partial agonist activity; reduced propensity to directly activate GABAA receptors (possibly including extrasynaptic receptors containing δ subunits); and reduced activity at other ion channel targets, including voltage-gated calcium channels. Although the precise sites where barbiturates interact with GABAA receptors has not been defined, the second and third transmembrane domains of the β subunit appear to be critical; binding may involve a pocket formed by β-subunit methionine 286 as well as α-subunit methionine 236. In addition to effects on GABAA receptors, barbiturates block AMPA receptors, and they inhibit glutamate release through an effect on P/Q-type high-voltage activated calcium channels. The combination of these various actions likely accounts for their diverse clinical activities.

Overdose

Main article: Barbiturate overdose Medical condition| Phenobarbital |

|---|

Phenobarbital causes a "depression" of the body's systems, mainly the central and peripheral nervous systems; thus, the main characteristic of phenobarbital overdose is a "slowing" of bodily functions, including decreased consciousness (even coma), bradycardia, bradypnea, hypothermia, and hypotension (in massive overdoses). Overdose may also lead to pulmonary edema and acute renal failure as a result of shock, and can result in death.

The electroencephalogram of a person with phenobarbital overdose may show a marked decrease in electrical activity, to the point of mimicking brain death. This is due to profound depression of the central nervous system, and is usually reversible.

Treatment of phenobarbital overdose is supportive, and consists mainly in the maintenance of airway patency (through endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation), correction of bradycardia and hypotension (with intravenous fluids and vasopressors, if necessary) and removal of as much drug as possible from the body. Depending on how much time has elapsed since ingestion of the drug, this may be accomplished through gastric lavage (stomach pumping) or use of activated charcoal. Hemodialysis is effective in removing phenobarbital from the body, and may reduce its half-life by up to 90%. No specific antidote for barbiturate poisoning is available. Picrotoxin may be little effective in overdose treatment.

British veterinarian Donald Sinclair, better known as "Siegfried Farnon" in the "All Creatures Great and Small" books of James Herriot, committed suicide at the age of 84 by injecting himself with an overdose of phenobarbital. Activist Abbie Hoffman also committed suicide by consuming phenobarbital, combined with alcohol, on April 12, 1989; the residue of around 150 pills was found in his body at autopsy. Also dying from an overdose in 1996 was actress/model Margaux Hemingway.

Pharmacokinetics

Phenobarbital has an oral bioavailability of about 90%. Peak plasma concentrations are reached eight to 12 hours after oral administration. It is one of the longest-acting barbiturates available – it remains in the body for a very long time (half-life of two to seven days) and has very low protein binding (20 to 45%). Phenobarbital is metabolized by the liver, mainly through hydroxylation and glucuronidation, and induces many isozymes of the cytochrome P450 system. Cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) is specifically induced by phenobarbital via the CAR/RXR nuclear receptor heterodimer. It is excreted primarily by the kidneys.

Veterinary uses

Phenobarbital is one of the initial drugs of choice to treat epilepsy in dogs, and is the initial drug of choice to treat epilepsy in cats.

It is also used to treat feline hyperesthesia syndrome in cats when antiobsessional therapies prove ineffective.

It may also be used to treat seizures in horses when benzodiazepine treatment has failed or is contraindicated.

Chemistry

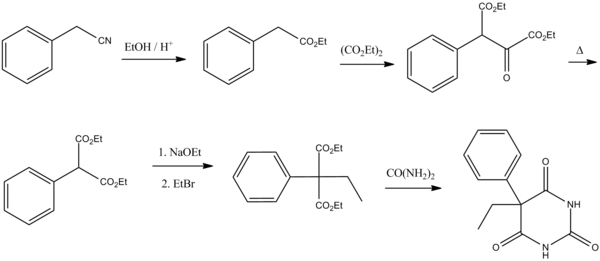

Phenobarbital (5-ethyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid or 5-ethyl-5-phenylhexahydropyrimindin-2,4,6-trione) has been synthesized in several different ways.

- Bayer & Co., DE 247952 (1911).

- M.T. Inman, W.P. Bitler, U.S. patent 2,358,072 (1944).

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01305a036, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01305a036instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77752-5, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77752-5instead.

There is no major difference between them.

The first method consists of ethanolysis of benzyl cyanide in the presence of acid, giving phenylacetic acid ethyl ester, the methylene group of which undergoes acylation using diethyloxalate, giving diethyl ester of phenyloxobutandioic acid, which upon heating easily loses carbon oxide and turns into phenylmalonic ester. Alkylation of the obtained product using ethyl bromide in the presence of sodium ethoxide leads to the formation of α-phenyl-α- ethylmalonic ester, the condensation of which with urea gives phenobarbital.

Another method of phenobarbital synthesis starts with condensation of benzyl cyanide with

diethylcarbonate in the presence of sodium ethoxide to give α-phenylcyanoacetic ester. Alkylation of the ester using ethyl bromide gives α-phenyl-α-ethylcyanoacetic ester, which is further converted into the 4-iminoderivative upon treatment with urea. Acidic hydrolysis of the resulting product gives phenobarbital.

History

The first barbiturate drug, barbital, was synthesized in 1902 by German chemists Emil Fischer and Joseph von Mering and was first marketed as Veronal by Friedr. Bayer et comp. By 1904, several related drugs, including phenobarbital, had been synthesized by Fischer. Phenobarbital was brought to market in 1912 by the drug company Bayer as the brand Luminal. It remained a commonly prescribed sedative and hypnotic until the introduction of benzodiazepines in the 1960s.

Phenobarbital's soporific, sedative and hypnotic properties were well known in 1912, but it was not yet known to be an effective anticonvulsant. The young doctor Alfred Hauptmann gave it to his epilepsy patients as a tranquilizer and discovered their seizures were susceptible to the drug. Hauptmann performed a careful study of his patients over an extended period. Most of these patients were using the only effective drug then available, bromide, which had terrible side effects and limited efficacy. On phenobarbital, their epilepsy was much improved: The worst patients suffered fewer and lighter seizures and some patients became seizure-free. In addition, they improved physically and mentally as bromides were removed from their regimen. Patients who had been institutionalised due to the severity of their epilepsy were able to leave and, in some cases, resume employment. Hauptman dismissed concerns that its effectiveness in stalling seizures could lead to patients suffering a build-up that needed to be "discharged". As he expected, withdrawal of the drug led to an increase in seizure frequency – it was not a cure. The drug was quickly adopted as the first widely effective anticonvulsant, though World War I delayed its introduction in the U.S.

In 1939 a German family asked Adolf Hitler to have their disabled son "put to sleep", the five-month-old boy was given Luminal after Hitler sent his own doctor to examine him. A few days later 15 psychiatrists were summoned to Hitler's Chancellery and directed to commence a clandestine euthanasia program. In 1940, at a clinic in Ansbach, Germany, around 50 intellectually disabled children were injected with Luminal and killed that way. A plaque was erected in their memory in 1988 in the local hospital at Feuchtwanger Strasse 38, although a newer plaque does not mention that patients were actively killed with barbiturates on site. Luminal was used in the Nazi "children's euthanasia" program through at least 1943.

Phenobarbital was used to treat neonatal jaundice by increasing liver metabolism and thus lowering bilirubin levels. In the 1950s, phototherapy was discovered, and became the standard treatment.

Phenobarbital was used for over 25 years as prophylaxis in the treatment of febrile seizures. Although an effective treatment in preventing recurrent febrile seizures, it had no positive effect on patient outcome or risk of developing epilepsy. The treatment of simple febrile seizures with anticonvulsant prophylaxis is no longer recommended.

References

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ (September 2004). "Phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in the 21st century: a critical review". Epilepsia. 45 (9): 1141–9. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.12704.x. PMID 15329080.

- ^ "Phenobarbital". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-12.

- ^ NICE (2005-10-27). "CG20 Epilepsy in adults and children: NICE guideline". NHS. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacists Group (2006). "4.8.1 Control of epilepsy". British National Formulary for Children. London: BMJ Publishing. pp. 255–6. ISBN 0-85369-676-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ British National Formulary 51

- Taylor S, Tudur Smith C, Williamson PR, Marson AG (2003). Taylor, Stephen (ed.). "Phenobarbitone versus phenytoin monotherapy for partial onset seizures and generalized onset tonic-clonic seizures". Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (2): CD002217. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002217. PMID 11687150. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tudur Smith C, Marson AG, Williamson PR (2003). Tudur Smith, Catrin (ed.). "Carbamazepine versus phenobarbitone monotherapy for epilepsy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001904. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001904. PMID 12535420. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacists Group (2006). "4.8.2 Drugs used in status epilepticus". British National Formulary for Children. London: BMJ Publishing. p. 269. ISBN 0-85369-676-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kälviäinen R, Eriksson K, Parviainen I (2005). "Refractory generalised convulsive status epilepticus : a guide to treatment". CNS Drugs. 19 (9): 759–68. doi:10.2165/00023210-200519090-00003. PMID 16142991.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - John M. Pellock, W. Edwin Dodson, Blaise F. D. Bourgeois (2001-01-01). Pediatric Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 1-888799-30-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Raj D Sheth (2005-03-30). "Neonatal Seizures". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- Booth D, Evans DJ (2004). Booth, David (ed.). "Anticonvulsants for neonates with seizures". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD004218. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004218.pub2. PMID 15495087. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- http://www.aafp.org/afp/980700ap/miller.html

- Trimble MR (1988). "Children of school age: the influence of antiepileptic drugs on behavior and intellect". Epilepsia. 29 Suppl 3: S15–9. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb05805.x. PMID 3066616.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8961191, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 8961191instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23205959, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 23205959instead. - ^ Rania Habal (2006-01-27). "Barbiturate Toxicity". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- "Barbiturate intoxication and overdose". MedLine Plus. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- King, Wayne (April 19, 1989). "Abbie Hoffman Committed Suicide Using Barbiturates, Autopsy Shows". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

-

Thomas, WB (2003). "Seizures and narcolepsy". In Dewey, Curtis W. (ed.) (ed.). A Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Press. ISBN 0-8138-1249-6.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Dodman, Nicholas. "Feline Hyperesthesia (FHS)". PetPlace.com. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

-

Editor, Cynthia M. Kahn; associate editor Scott Line (February 8, 2005). Kahn, Cynthia M., Line, Scott, Aiello, Susan E. (ed.) (ed.). The Merck Veterinary Manual (9th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-911910-50-6.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sneader, Walter (2005-06-23). Drug Discovery. John Wiley and Sons. p. 369. ISBN 0-471-89979-8.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Ole Daniel Enersen. "Alfred Hauptmann". Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- Scott,, Donald F (1993-02-15). The History of Epileptic Therapy. Taylor & Francis. pp. 59–65. ISBN 1-85070-391-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Zoech, Irene (12 October 2003). "Named: the baby boy who was Nazis' first euthanasia victim". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

The case was to provide the rationale for a secret Nazi decree that led to 'mercy killings' of almost 300,000 mentally and physically handicapped people. The Kretschmars wanted their son dead but most of the other children were forcibly taken from their parents to be killed.

- Wesley J. Smith (26 March 2006). "Killing Babies, Compassionately". Weekly Standard. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

Hitler later signed a secret decree permitting the euthanasia of disabled infants. Sympathetic physicians and nurses from around the country--many not even Nazi party members--cooperated in the horror that followed. Formal 'protective guidelines' were created, including the creation of a panel of 'expert referees,' which judged which infants were eligible for the program.

- Kaelber, Lutz (8 March 2013). "Kinderfachabteilung Ansbach". Sites of Nazi "Children's 'Euthanasia'" Crimes and Their Commemoration in Europe. University of Vermont. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

In the late 1980s, important developments occurred at the clinic that led to the first publication on the subject and the display of two plaques. Dr. Reiner Weisenseel wrote his dissertation under Dr. Athen, then the director of the Ansbacher Bezirkskrankenhaus, on the involvement of the clinic in Euthanasia crimes, including the operation of the Kinderfachabteilung. In 1988 two members of the Green Party as well as the regional diet (Bezirkstag) were horrified to find portraits of physicians involved in Nazi euthanasia crimes among the honorary display of medical personnel in the administrative building, and they successfully petitioned to have these portraits removed. Since 1992 a plaque hangs in the entry hall way of the administrative building. It reads: 'In the Third Reich the Ansbach facility delivered to their death more than 2000 of the patients entrusted to it as life unworthy of living: They were transferred to killing facilities or starved to death. In their own way many people incurred responsibility.' It continues: 'Half a century later full of shame we commemorate the victims and call to remember the Fifth Commandment.' The active killing of children specifically transferred to the clinic to be murdered is not noted. The plaque does not address that that euthanasia victims were not only starved or transported to gassing facilities but actively killed with barbiturates on site.

- Binder, Johann (October 2011). "Die Heil- und Pfl egeanstalt Ansbach während des Nationalsozialismus" (PDF). Bezirksklinikum Ansbach (in German). Bezirkskliniken Mittelfranken. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Kaelber, Lutz (Spring 2013). "Jewish Children with Disabilities and Nazi "Euthanasia" Crimes" (PDF). The Bulletin of the Carolyn and Leonard Miller Center for Holocaust Studies. University of Vermont. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

Two Polish physicians reported at the time that 235 children from ages up to 14 were listed in the booklet, of whom 221 had died. An investigation revealed that the medical records of the children had been falsified, as those records showed a far lower dosage of Luminal given to them than was entered into the Luminal booklet. For example, the medical records for Marianna N. showed for 16 January 1943 (she died on that day) a dosage of .1 gram of Luminal, whereas the Luminal booklet showed the actual dosage as .4 grams, or four times the dosage recommended for her body weight.

- Rachel Sheremeta Pepling (June 2005). "Phenobarbital". Chemical and Engineering News. 83 (25). Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- John M. Pellock, W. Edwin Dodson, Blaise F. D. Bourgeois (2001-01-01). Pediatric Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 169. ISBN 1-888799-30-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robert Baumann (2005-02-14). "Febrile Seizures". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- various (March 2005). "Diagnosis and management of epilepsies in children and young people" (PDF). Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. p. 15. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

External links

| GABAA receptor positive modulators | |

|---|---|

| Alcohols | |

| Barbiturates |

|

| Benzodiazepines |

|

| Carbamates | |

| Flavonoids |

|

| Imidazoles | |

| Kava constituents | |

| Monoureides | |

| Neuroactive steroids |

|

| Nonbenzodiazepines | |

| Phenols | |

| Piperidinediones | |

| Pyrazolopyridines | |

| Quinazolinones | |

| Volatiles/gases |

|

| Others/unsorted |

|

| See also: Receptor/signaling modulators • GABA receptor modulators • GABA metabolism/transport modulators | |

| Hypnotics/sedatives (N05C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABAA |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GABAB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2-Adrenergic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HT2A |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orexin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2δ VDCC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||