| Revision as of 19:51, 9 March 2013 editMark Foskey (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,407 edits →Mechanism of action: "like morphine" was placed so that it modified "auerbach's plexus, when I think it should modify Lop. H.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:17, 22 December 2024 edit undoWhywhenwhohow (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers49,185 edits rank | ||

| (643 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Medicine used to reduce diarrhea}} | |||

| {{drugbox | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2024}} | |||

| | Verifiedfields = changed | |||

| {{cs1 config |name-list-style=vanc |display-authors=6}} | |||

| {{Infobox drug | |||

| | Verifiedfields = changed | |||

| | Watchedfields = changed | | Watchedfields = changed | ||

| | verifiedrevid = 416898838 | | verifiedrevid = 416898838 | ||

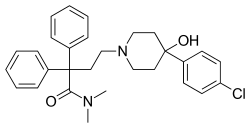

| | IUPAC_name = 4-- ''N,N''-dimethyl-2,2-diphenylbutanamide | |||

| | image = Loperamide.svg | | image = Loperamide.svg | ||

| | width = 250 | |||

| | image2 = Loperamide2mg.JPG | |||

| | alt = | |||

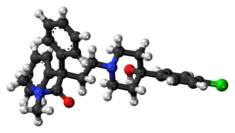

| | image2 = Loperamide 3D ball.png | |||

| | width2 = 235 | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | USAN = Loperamide hydrochloride | |||

| <!--Clinical data--> | <!-- Clinical data --> | ||

| | pronounce = {{IPAc-en|l|oʊ|ˈ|p|ɛr|ə|m|aɪ|d}} | |||

| | tradename = Imodium | |||

| | tradename = Imodium, others<ref name=Names/> | |||

| | Drugs.com = {{drugs.com|monograph|loperamide-hydrochloride}} | | Drugs.com = {{drugs.com|monograph|loperamide-hydrochloride}} | ||

| | MedlinePlus = a682280 | | MedlinePlus = a682280 | ||

| | DailyMedID = Loperamide | |||

| | pregnancy_category = B<ref>"." ''DailyMed''.</ref> | |||

| | pregnancy_AU = B3 | |||

| | routes_of_administration = ] | |||

| | ATC_prefix = A07 | |||

| | ATC_suffix = DA03 | |||

| | ATC_supplemental = <br />{{ATC|A07|DA05}} (oxide) | |||

| | legal_AU = S2 | |||

| | legal_BR = C1 | |||

| | legal_BR_comment = <ref>{{cite web |author=Anvisa |author-link=Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency |date=31 March 2023 |title=RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial |trans-title=Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control|url=https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-784-de-31-de-marco-de-2023-474904992 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230803143925/https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-784-de-31-de-marco-de-2023-474904992 |archive-date=3 August 2023 |access-date=16 August 2023 |publisher=] |language=pt-BR |publication-date=4 April 2023}}</ref> | |||

| | legal_CA = OTC | | legal_CA = OTC | ||

| | legal_UK = GSL | | legal_UK = GSL | ||

| | legal_US = OTC | | legal_US = OTC | ||

| | legal_US_comment = / Rx-only<ref>{{cite web | title=Loperamide hydrochloride capsule | website=DailyMed | date=30 September 2022 | url=https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=72a7ae47-cdf3-4949-b9f8-f29b153f787f | access-date=8 January 2024 | archive-date=14 September 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230914040736/https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=72a7ae47-cdf3-4949-b9f8-f29b153f787f | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | routes_of_administration = oral, insufflation | |||

| <!--Pharmacokinetic data--> | <!-- Pharmacokinetic data --> | ||

| | bioavailability = |

| bioavailability = 0.3% | ||

| | protein_bound = 97% | | protein_bound = 97% | ||

| | metabolism = ] | | metabolism = ] (extensive) | ||

| | elimination_half-life = |

| elimination_half-life = 9–14 hours<ref name=AHFS2015/> | ||

| | excretion = Feces (30–40%), urine (1%) | |||

| <!--Identifiers--> | <!-- Identifiers --> | ||

| | IUPHAR_ligand = 7215 | |||

| | CASNo_Ref = {{cascite|correct|CAS}} | |||

| | CAS_number_Ref = {{cascite|correct|??}} | | CAS_number_Ref = {{cascite|correct|??}} | ||

| | CAS_number = 53179-11-6 | | CAS_number = 53179-11-6 | ||

| | CAS_supplemental = <br />{{CAS|34552-83-5}} (with HCl) | |||

| | ATC_prefix = A07 | |||

| | ATC_suffix = DA03 | |||

| | ATC_supplemental = <br />{{ATC|A07|DA05}} (oxide) | |||

| | PubChem = 3955 | | PubChem = 3955 | ||

| | DrugBank_Ref = {{drugbankcite|changed|drugbank}} | | DrugBank_Ref = {{drugbankcite|changed|drugbank}} | ||

| Line 44: | Line 58: | ||

| | ChEMBL_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} | | ChEMBL_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} | ||

| | ChEMBL = 841 | | ChEMBL = 841 | ||

| | synonyms = R-18553 | |||

| <!--Chemical data--> | <!-- Chemical data --> | ||

| | IUPAC_name = 4--''N,N''-dimethyl-2,2-diphenylbutanamide | |||

| | C=29 | H=33 | Cl=1 | N=2 | O=2 | |||

| | C=29 | H=33 | Cl=1 | N=2 | O=2 | |||

| | molecular_weight = 477.037 g/mol (513.506 with HCl) | |||

| | |

| SMILES = ClC1=CC=C(C2(CCN(CC2)CCC(C3=CC=CC=C3)(C(N(C)C)=O)C4=CC=CC=C4)O)C=C1 | ||

| | InChI = 1/C29H33ClN2O2/c1-31(2)27(33)29(24-9-5-3-6-10-24,25-11-7-4-8-12-25)19-22-32-20-17-28(34,18-21-32)23-13-15-26(30)16-14-23/h3-16,34H,17-22H2,1-2H3 | |||

| | StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} | | StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} | ||

| | StdInChI = 1S/C29H33ClN2O2/c1-31(2)27(33)29(24-9-5-3-6-10-24,25-11-7-4-8-12-25)19-22-32-20-17-28(34,18-21-32)23-13-15-26(30)16-14-23/h3-16,34H,17-22H2,1-2H3 | | StdInChI = 1S/C29H33ClN2O2/c1-31(2)27(33)29(24-9-5-3-6-10-24,25-11-7-4-8-12-25)19-22-32-20-17-28(34,18-21-32)23-13-15-26(30)16-14-23/h3-16,34H,17-22H2,1-2H3 | ||

| Line 55: | Line 69: | ||

| | StdInChIKey = RDOIQAHITMMDAJ-UHFFFAOYSA-N | | StdInChIKey = RDOIQAHITMMDAJ-UHFFFAOYSA-N | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!-- Definition and medical uses --> | |||

| '''Loperamide''', sold under the brand name '''Imodium''', among others,<ref name=Names>Drugs.com {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923230214/http://www.drugs.com/international/loperamide.html |date=23 September 2015 }} Page accessed 4 September 2015</ref> is a ] of the ] class used to decrease the frequency of ].<ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/loperamide/about-loperamide/|title=About loperamide|date=11 April 2024|website=nhs.uk}}</ref><ref name=AHFS2015>{{cite web|title=Loperamide Hydrochloride|url=https://www.drugs.com/monograph/loperamide-hydrochloride.html|publisher=The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists|access-date=25 August 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150907231103/http://www.drugs.com/monograph/loperamide-hydrochloride.html|archive-date=7 September 2015}}</ref> It is often used for this purpose in ], ], ],<ref name=AHFS2015/> ], and ].<ref name="auto"/> It is not recommended for those with ], mucus in the stool, or ].<ref name=AHFS2015/> The medication is ].<ref name=AHFS2015/> | |||

| <!-- Side effects --> | |||

| '''Loperamide''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|l|oʊ|ˈ|p|ɛr|ə|m|aɪ|d}}; '''R-18553'''{{clarify|date=November 2011}}), a synthetic ] derivative,<ref></ref> is an ] ] used against ] resulting from ] or ]. In most countries it is available generically and under brand names such as '''Lopex''', '''Imodium''', '''Dimor''', '''Fortasec''', '''Lopedium''', and '''Pepto Diarrhea Control'''. It was developed at ].<ref>{{ cite journal | author = Stokbroekx, R. A.; Vanenberk, J.; Van Heertum, A. H. M. T.; Van Laar, G. M. L. W.; Van der Aa, M. J. M. C.; Van Bever, W. F. M.; Janssen, P. A. J. | title = Synthetic Antidiarrheal Agents. 2,2-Diphenyl-4-(4'-aryl-4'-hydroxypiperidino)butyramides | journal = Journal of Medicinal Chemistry | volume = 16 | issue = 7 | pages = 782–786 | year = 1973 | pmid = | doi = 10.1021/jm00265a009 }}</ref> | |||

| Common side effects include ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name=AHFS2015/> It may increase the risk of ].<ref name=AHFS2015/> Loperamide's safety in ] is unclear, but no evidence of harm has been found.<ref name=AG2015>{{cite web|title=Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database|url=http://www.tga.gov.au/hp/medicines-pregnancy.htm|work=Australian Government|access-date=22 April 2014|date=3 March 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140408040902/http://www.tga.gov.au/hp/medicines-pregnancy.htm |archive-date=8 April 2014}}</ref> It appears to be safe in ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Loperamide use while Breastfeeding|url=https://www.drugs.com/breastfeeding/loperamide.html|access-date=26 August 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150908034709/http://www.drugs.com/breastfeeding/loperamide.html|archive-date=8 September 2015}}</ref> It is an ] with no significant absorption from the gut and does not cross the ] when used at normal doses.<ref name=NCI2015Dic>{{cite web|title=loperamide hydrochloride|url=http://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-drug?CdrID=41911|website=NCI Drug Dictionary|access-date=26 August 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150907211727/http://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-drug?CdrID=41911|archive-date=7 September 2015|date=2 February 2011}}</ref> It works by slowing the contractions of the ].<ref name=AHFS2015/> | |||

| <!-- History, society, and culture --> | |||

| Loperamide was first made in 1969 and used medically in 1976.<ref name="Oxford University Press">{{cite book|vauthors=Patrick GL|title=An introduction to medicinal chemistry|date=2013|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=9780199697397|pages=644|edition=Fifth|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pj7xJRuhZxUC&pg=PA644|access-date=17 December 2020|archive-date=14 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230114195405/https://books.google.com/books?id=Pj7xJRuhZxUC&pg=PA644|url-status=live}}</ref> It is on the ].<ref name="WHO22nd">{{cite book | vauthors = ((World Health Organization)) | title = World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021) | year = 2021 | hdl = 10665/345533 | author-link = World Health Organization | publisher = World Health Organization | location = Geneva | id = WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02 | hdl-access=free }}</ref> Loperamide is available as a ].<ref name=AHFS2015/><ref name=Ric2013>{{cite book| vauthors = Hamilton RJ |title=Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia|date=2013|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|location=|isbn=9781449673611|pages = 217|edition=14|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zJay-fZCFGgC&pg=PA217|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305005322/https://books.google.com/books?id=zJay-fZCFGgC&pg=PA217|archive-date=5 March 2016}}</ref> In 2022, it was the 297th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 400,000 prescriptions.<ref name="Top 300 of 2022">{{cite web | title=The Top 300 of 2022 | url=https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx | website=ClinCalc | access-date=30 August 2024 | archive-date=30 August 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240830202410/https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx | url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = Loperamide Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022 | website = ClinCalc | url = https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Loperamide | access-date = 30 August 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Medical uses== | ==Medical uses== | ||

| Loperamide is effective for the treatment of a number of types of |

Loperamide is effective for the treatment of a number of types of diarrhea.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hanauer SB | title = The role of loperamide in gastrointestinal disorders | journal = Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders | volume = 8 | issue = 1 | pages = 15–20 | date =Winter 2008 | pmid = 18477966 }}</ref> This includes control of acute nonspecific diarrhea, mild ], irritable bowel syndrome, chronic diarrhea due to bowel resection, and chronic diarrhea secondary to inflammatory bowel disease. It is also useful for reducing ] output. ]s for loperamide also include chemotherapy-induced diarrhea, especially related to ] use. | ||

| Loperamide should not be used as the primary treatment in cases of ], acute exacerbation of ], or bacterial ].<ref name=drugs.com>{{cite web|url=https://www.drugs.com/pro/loperamide.html|title=Loperamide|access-date=14 May 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160520143952/http://www.drugs.com/pro/loperamide.html|archive-date=20 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Loperamide is often compared to ]. Studies suggest that loperamide is more effective and has lower neural side effects.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Miftahof R |date=2009 |title=Mathematical Modeling and Simulation in Enteric Neurobiology |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=3Qyd9TmOY5EC&pg=PA18 |publisher=World Scientific |isbn=9789812834812 |pages = 18|url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170728102724/https://books.google.com/books?id=3Qyd9TmOY5EC&pg=PA18&dq=|archive-date=28 July 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| veditors = Benson A, Chakravarthy A, Hamilton SR, Elin S |date=2013|title=Cancers of the Colon and Rectum: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Management |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=afb1AAAAQBAJ&q=D&pg=PA225 |publisher=Demos Medical Publishing|isbn=9781936287581 |pages = 225|url-status=live |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170908145128/https://books.google.com/books?id=afb1AAAAQBAJ&pg=PA225&dq=D#v=onepage&q=D&f=false|archive-date=8 September 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Zuckerman JN |date=2012|title=Principles and Practice of Travel Medicine|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FXxksru7IQYC&pg=PA203|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=9781118392089|pages = 203|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170908145128/https://books.google.com/books?id=FXxksru7IQYC&pg=PA203&dq=|archive-date=8 September 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ==Side effects== | |||

| ]s most commonly associated with loperamide are constipation (which occurs in 1.7–5.3% of users), dizziness (up to 1.4%), nausea (0.7–3.2%), and abdominal cramps (0.5–3.0%).<ref name=ReferenceA>{{cite web |url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/017694s050lbl.pdf |title=Imodium label |publisher=U.S. ] (FDA) |access-date=21 April 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140423055633/http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/017694s050lbl.pdf |archive-date=23 April 2014 }}</ref> Rare, but more serious, side effects include toxic megacolon, ], ], anaphylaxis/allergic reactions, ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://online.epocrates.com/noFrame/showPage.do;jsessionid=FB4C4C42205138677A3F9E475E6C6299?method=drugs&MonographId=44&ActiveSectionId=5|title=loperamide adverse reactions|access-date=14 May 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181101071123/https://online.epocrates.com/noFrame/showPage.do;jsessionid=FB4C4C42205138677A3F9E475E6C6299?method=drugs&MonographId=44&ActiveSectionId=5|archive-date=1 November 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref> The most frequent symptoms of loperamide overdose are drowsiness, vomiting, and abdominal pain, or burning.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Litovitz T, Clancy C, Korberly B, Temple AR, Mann KV | title = Surveillance of loperamide ingestions: an analysis of 216 poison center reports | journal = Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology | volume = 35 | issue = 1 | pages = 11–9 | date = 1997 | pmid = 9022646 | doi = 10.3109/15563659709001159 }}</ref> High doses may result in heart problems such as ]s.<ref>{{cite web|title=Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Loperamide (Imodium): Drug Safety Communication - Serious Heart Problems With High Doses From Abuse and Misuse|url=https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm505303.htm|website=U.S. ] (FDA)|access-date=12 June 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160611093318/https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm505303.htm|archive-date=11 June 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ===Contraindications=== | |||

| Treatment should be avoided in the presence of high ] or if the ]. Treatment is not recommended for people who could have negative effects from rebound ]. If suspicion exists of diarrhea associated with organisms that can penetrate the intestinal walls, such as ] or '']'', loperamide is ] as a primary treatment.<ref name=drugs.com/> Loperamide treatment is not used in symptomatic '']'' infections, as it increases the risk of toxin retention and precipitation of toxic megacolon. | |||

| Loperamide should be administered with caution to people with ] due to reduced ].<ref>{{ cite web | title = rxlist.com | year = 2005 | url = http://www.rxlist.com/imodium-drug/indications-dosage.htm | url-status = live | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20121127021744/http://www.rxlist.com/imodium-drug/indications-dosage.htm | archive-date = 27 November 2012 | df = dmy-all }}</ref> Additionally, caution should be used when treating people with advanced ], as cases of both viral and bacterial toxic megacolon have been reported. If abdominal distension is noted, therapy with loperamide should be discontinued.<ref name=accessdata.fda.gov>{{cite web|url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory|title=Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products|publisher=U.S. ] (FDA)|access-date=14 May 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160506041852/http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory|archive-date=6 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ===Children=== | |||

| The use of loperamide in children under two years is not recommended. Rare reports of fatal ] associated with ] have been made. Most of these reports occurred in the setting of acute ], overdose, and with very young children less than two years of age.<ref>{{ cite web | url = http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?id=6651 | title = Imodium (Loperamide Hydrochloride) Capsule | work = DailyMed | publisher = NIH | url-status = live | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100413032222/http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?id=6651 | archive-date = 13 April 2010 | df = dmy-all }}</ref> A review of loperamide in children under 12 years old found that serious adverse events occurred only in children under three years old. The study reported that the use of loperamide should be contraindicated in children who are under 3, systemically ill, malnourished, moderately dehydrated, or have bloody diarrhea.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=Li ST, Grossman DC, Cummings P | title = Loperamide therapy for acute diarrhea in children: systematic and meta-analysis | journal = PLOS Medicine | volume = 4 | issue = 3 | date = 2007 | pages = e98 | pmid=17388664 | doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040098 | pmc=1831735 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| In 1990, all formulations for children of the antidiarrheal loperamide were banned in Pakistan.<ref>{{ cite web|url=http://www.essentialdrugs.org/edrug/archive/199708/msg00056.php |title=E-DRUG: Chlormezanone |publisher=Essentialdrugs.org |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110726035911/http://www.essentialdrugs.org/edrug/archive/199708/msg00056.php |archive-date=26 July 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| The ] in the United Kingdom recommends that loperamide should only be given to children under the age of twelve if prescribed by a doctor. Formulations for children are only available on prescription in the UK.<ref>{{cite web |date=20 December 2018 |title=Loperamide: a medicine used to treat diarrhoea |url=https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/loperamide/ |access-date=7 October 2023 |website=] }}</ref> | |||

| ===Pregnancy and breast feeding=== | |||

| Loperamide is not recommended in the United Kingdom for use during ] or by ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nhs.uk/medicine-guides/pages/MedicineOverview.aspx?condition=Diarrhoea&medicine=imodium|title=Medicines information links - NHS Choices|access-date=14 May 2016|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140110171045/http://www.nhs.uk/medicine-guides/pages/MedicineOverview.aspx?condition=Diarrhoea&medicine=imodium|archive-date=10 January 2014}}</ref> Studies in rat models have shown no ]icity, but sufficient studies in humans have not been conducted.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#labelinfo|title=Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products|publisher=U.S. ] (FDA) |access-date=14 May 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160506041852/http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#labelinfo|archive-date=6 May 2016}}</ref> One controlled, prospective study of 89 women exposed to loperamide during their first trimester of pregnancy showed no increased risk of malformations. This, however, was only one study with a small sample size.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Einarson A, Mastroiacovo P, Arnon J, Ornoy A, Addis A, Malm H, Koren G | title = Prospective, controlled, multicentre study of loperamide in pregnancy | journal = Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = 14 | issue = 3 | pages = 185–7 | date = March 2000 | pmid = 10758415 | doi = 10.1155/2000/957649 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Loperamide can be present in breast milk and is not recommended for breastfeeding mothers.<ref name=accessdata.fda.gov/> | |||

| ==Drug interactions== | |||

| Loperamide is a substrate of ]; therefore, the concentration of loperamide increases when given with a P-glycoprotein inhibitor.<ref name=ReferenceA/> Common P-glycoprotein inhibitors include ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/druginteractionslabeling/ucm093664.htm#PgpTransport|title=Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers|publisher=U.S. ] (FDA) |access-date=14 May 2016|url-status=live|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160510152158/https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/DrugInteractionsLabeling/ucm093664.htm#PgpTransport|archive-date=10 May 2016}}</ref> Loperamide can decrease the absorption of some other drugs. As an example, ] concentrations can decrease by half when given with loperamide.<ref name=ReferenceA/> | |||

| Loperamide is an antidiarrheal agent, which decreases intestinal movement. As such, when combined with other antimotility drugs, the risk of constipation is increased. These drugs include other ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s.<ref>{{cite web |title=Loperamide Drug Interactions - Epocrates Online |url=https://online.epocrates.com/noFrame/showPage.do?method=drugs&MonographId=44&ActiveSectionId=4 |website=online.epocrates.com |access-date=5 November 2020 |archive-date=1 November 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181101070900/https://online.epocrates.com/noFrame/showPage.do?method=drugs&MonographId=44&ActiveSectionId=4 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Mechanism of action== | ==Mechanism of action== | ||

| ] | |||

| Loperamide is an opioid-receptor ] and acts on the ] in the ] of the large intestine. It works like ], decreasing the activity of the myenteric plexus, which decreases the tone of the longitudinal and circular ]s of the intestinal wall.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00836|title=DrugBank: Loperamide|access-date=14 May 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160510135146/http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00836|archive-date=10 May 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.drugs.com/mmx/loperamide-hydrochloride.html|title=Loperamide Hydrochloride Drug Information, Professional|access-date=14 May 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160503123442/http://www.drugs.com/mmx/loperamide-hydrochloride.html|archive-date=3 May 2016}}</ref> This increases the time material stays in the intestine, allowing more water to be absorbed from the fecal matter. It also decreases colonic mass movements and suppresses the ].<ref>{{ cite book | vauthors = Katzung BG | title = Basic and Clinical Pharmacology | edition = 9th | year = 2004 | publisher = Lange Medical Books/McGraw Hill | isbn = 978-0-07-141092-2 }}{{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Loperamide's circulation in the bloodstream is limited in two ways. Efflux by P-glycoprotein in the intestinal wall reduces the passage of loperamide, and the fraction of drug crossing is then further reduced through ] by the liver.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R0W1ErpsQpkC|title=Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry| vauthors = Lemke TL, Williams DA |date=2008|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |isbn=9780781768795 |pages = 675 |url-status=live |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170908145128/https://books.google.com/books?id=R0W1ErpsQpkC |archive-date=8 September 2017 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dufek MB, Knight BM, Bridges AS, Thakker DR | title = P-glycoprotein increases portal bioavailability of loperamide in mouse by reducing first-pass intestinal metabolism | journal = Drug Metabolism and Disposition | volume = 41 | issue = 3 | pages = 642–50 | date = March 2013 | pmid = 23288866 | doi = 10.1124/dmd.112.049965 | df = dmy-all | s2cid = 11014783 }}</ref> Loperamide metabolizes into an ]-like compound, but is unlikely to exert ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kalgutkar AS, Nguyen HT | title = Identification of an N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-like metabolite of the antidiarrheal agent loperamide in human liver microsomes: underlying reason(s) for the lack of neurotoxicity despite the bioactivation event | journal = Drug Metabolism and Disposition | volume = 32 | issue = 9 | pages = 943–52 | date = September 2004 | pmid = 15319335 | url = http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/content/32/9/943 | url-status = live | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170908145128/http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/content/32/9/943 | df = dmy-all | archive-date = 8 September 2017 }}</ref> | |||

| Loperamide is an ]-receptor ] and acts on the ] in the ] of the large intestine; by itself it does not affect the ]. | |||

| ===Blood–brain barrier=== | |||

| Like ], it works by decreasing the activity of the ], which decreases the tone of the longitudinal ]s but increases the tone of circular ] of the intestinal wall. This increases the amount of time substances stay in the intestine, allowing for more water to be absorbed out of the fecal matter. Loperamide also decreases colonic mass movements and suppresses the ].<ref>{{ cite book | author = Katzung, B. G. | title = Basic and Clinical Pharmacology | edition = 9th | year = 2004 | isbn = 0-07-141092-9 }}{{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Efflux by P-glycoprotein also prevents circulating loperamide from effectively crossing the blood-brain barrier,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Upton RN | title = Cerebral uptake of drugs in humans | journal = Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology | volume = 34 | issue = 8 | pages = 695–701 | date = August 2007 | pmid = 17600543 | doi = 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04649.x | s2cid = 41591261 }}</ref> so it can generally only antagonize muscarinic receptors in the ], and currently has a score of one on the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.agingbraincare.org/uploads/products/ACB_scale_-_legal_size.pdf |title=Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale |access-date=23 September 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180307142553/http://www.agingbraincare.org/uploads/products/ACB_scale_-_legal_size.pdf |archive-date=7 March 2018 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Concurrent administration of P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as ] potentially allows loperamide to cross the blood-brain barrier and produce central morphine-like effects. At high doses (>70mg), loperamide can saturate P-glycoprotein (thus overcoming the efflux) and produce euphoric effects.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Antoniou T, Juurlink DN | title = Loperamide abuse | journal = CMAJ | volume = 189 | issue = 23 | pages = E803 | date = June 2017 | pmid = 28606977 | pmc = 5468105 | doi = 10.1503/cmaj.161421 }}</ref> Loperamide taken with quinidine was found to produce respiratory depression, indicative of central opioid action.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sadeque AJ, Wandel C, He H, Shah S, Wood AJ | title = Increased drug delivery to the brain by P-glycoprotein inhibition | journal = Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics | volume = 68 | issue = 3 | pages = 231–7 | date = September 2000 | pmid = 11014404 | doi = 10.1067/mcp.2000.109156 | s2cid = 38467170 }}</ref> | |||

| High doses of loperamide have been shown to cause a mild ] during preclinical studies, specifically in mice, rats, and rhesus monkeys. Symptoms of mild opiate withdrawal were observed following abrupt discontinuation of long-term treatment of animals with loperamide.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yanagita T, Miyasato K, Sato J | title = Dependence potential of loperamide studied in rhesus monkeys | journal = NIDA Research Monograph | volume = 27 | pages = 106–13 | year = 1979 | pmid = 121326 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nakamura H, Ishii K, Yokoyama Y, Motoyoshi S, Suzuki K, Sekine Y, Hashimoto M, Shimizu M | title = | language = ja | journal = Yakugaku Zasshi | volume = 102 | issue = 11 | pages = 1074–85 | date = November 1982 | pmid = 6892112 | doi = 10.1248/yakushi1947.102.11_1074 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Crossing the blood–brain barrier=== | |||

| Concurrent administration of P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as ] and its other isomer ] (although much higher doses must be used), ]s like ] (Prilosec OTC) and even ] (] as the active ingredient) could potentially allow loperamide to cross the ]. It should however be noted that only quinidine with loperamide was found to produce respiratory depression, indicative of central opioid action.<ref>{{ cite journal | author = Sadeque, A. J.; Wandel, C.; He, H.; Shah, S.; Wood, A. J. | title = Increased Drug Delivery to the Brain by P-glycoprotein Inhibition | journal = Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics | volume = 68 | issue = 3 | pages = 231–237 | year = 2000 | month = September | pmid = 11014404 | doi = 10.1067/mcp.2000.109156 }}</ref> | |||

| == Chemistry == | |||

| Many physicians and pharmacists believe that loperamide does not cross the blood–brain barrier. In fact, however, loperamide does cross this barrier, although it is immediately pumped back out into non–central nervous system (CNS) circulation by ]. While this mechanism effectively shields the CNS from exposure (and thus risk of CNS tolerance/dependence) to loperamide, many drugs are known to inhibit P-glycoprotein and may thus render the CNS vulnerable to opiate agonism by loperamide.<ref>{{ cite pmid | 17600543 }}</ref> | |||

| === Synthesis === | |||

| Loperamide is synthesized starting from the ] 3,3-diphenyldihydrofuran-2(3H)-one and ethyl 4-oxopiperidine-1-carboxylate, on a lab scale.<ref name = "Stokbroekx_1973">{{cite journal | vauthors = Stokbroekx RA, Vandenberk J, Van Heertum AH, Van Laar GM, Van der Aa MJ, Van Bever WF, Janssen PA | title = Synthetic antidiarrheal agents. 2,2-Diphenyl-4-(4'-aryl-4'-hydroxypiperidino)butyramides | journal = Journal of Medicinal Chemistry | volume = 16 | issue = 7 | pages = 782–786 | date = July 1973 | pmid = 4725924 | doi = 10.1021/jm00265a009 }}</ref> On a large scale a similar synthesis is followed, except that the lactone and piperidinone are produced from cheaper materials rather than purchased.<ref>{{cite patent | inventor = Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ | country = US | number = 3714159 | gdate = 1973 }}</ref><ref>{{cite patent | inventor = Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ | country = US | number = 3884916 | gdate = 1975 }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Only when very high doses are taken does enough accumulate in the brain to produce typical ] effects, lasting for a number of hours (just as typical ] would).<ref>{{ cite journal | author = Litovitz, T.; Clancy, C.; Korberly, B.; Temple, A. R.; Mann, K. V. | title = Surveillance of Loperamide Ingestions: An Analysis of 216 Poison Center Reports | journal = Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology | year = 1997 | volume = 35 | issue = 1 | pages = 11–19 | pmid = 9022646 }}</ref><ref>{{ cite journal | author = Sklerov, J.; Levine, B.; Moore, K. A.; Allan, C.; Fowler, D. | title = Tissue Distribution of Loperamide and N-desmethylloperamide Following a Fatal Overdose | journal = Journal of Analytical Toxicology | year = 2005 | month = October | volume = 29 | issue = 7 | pages = 750–754 | pmid = 16419413 }}</ref> | |||

| === Physical properties === | |||

| However, loperamide has been shown to cause a mild ] during preclinical studies, specifically in mice, rats, and rhesus monkeys. Symptoms of mild opiate withdrawal have been observed following abrupt discontinuation of long-term therapy with loperamide.<ref>{{ cite journal | author = Yanagita, T.; Miyasato, K.; Sato, J. | title = Dependence Potential of Loperamide Studied in Rhesus Monkeys | journal = NIDA Research Monograph | volume = 27 | issue = | pages = 106–113 | year = 1979 | pmid = 121326 }}</ref><ref>{{ cite journal | author = Nakamura, H.; Ishii, K.; Yokoyama, Y. ''et al.'' | title = | language = Japanese | journal = Yakugaku Zasshi | volume = 102 | issue = 11 | pages = 1074–1085 | year = 1982 | month = November | pmid = 6892112 }}</ref> | |||

| Loperamide is typically manufactured as the hydrochloride salt. Its main ] has a ] of 224 °C and a second polymorph exists with a melting point of 218 °C. A ] form has been identified which melts at 190 °C.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Van Rompay J, Carter JE | title = Loperamide hydrochloride. | journal = Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances | date = January 1990 | volume = 19 | pages = 341–365 | publisher = Academic Press | veditors = Florey K |doi=10.1016/s0099-5428(08)60372-x| isbn = 9780122608193 }}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| ==Contraindications== | |||

| Loperamide hydrochloride was first synthesized in 1969<ref name="Oxford University Press"/> by ] from ] in ], Belgium, following previous discoveries of ] (1956) and ] (1960).<ref>{{cite book|vauthors=Florey K|date=1991|title=Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology, Volume 19|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5ndDXC2L5Q8C&pg=PA342|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=9780080861142|pages=342|access-date=18 May 2016|archive-date=14 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230114195404/https://books.google.com/books?id=5ndDXC2L5Q8C&pg=PA342|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The use of loperamide (Imodium) in children under 2 years is not recommended. There have been rare reports of fatal ] associated with ]. Most of these reports occurred in the setting of acute ], overdose, and with very young children less than two years of age.<ref>{{ cite web | url = http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?id=6651 | title = Imodium (Loperamide Hydrochloride) Capsule | work = DailyMed | publisher = NIH }}</ref> In 1990, all | |||

| pediatric formulations of the antidiarrheal loperamide (Imodium and others) were banned in ].<ref>{{ cite web | url = http://www.essentialdrugs.org/edrug/archive/199708/msg00056.php | title = E-DRUG: Chlormezanone | publisher = Essentialdrugs.org }}</ref> | |||

| The first clinical reports on loperamide were published in 1973 in the'' ]''<ref name = "Stokbroekx_1973" /> with the inventor being one of the authors. The trial name for it was "R-18553".<ref>{{cite journal | pmid = 4611432 | volume=24 | issue=10 | title=Loperamide (R 18 553), a novel type of antidiarrheal agent. Part 6: Clinical pharmacology. Placebo-controlled comparison of the constipating activity and safety of loperamide, diphenoxylate and codeine in normal volunteers | year=1974 | journal=Arzneimittelforschung | pages=1653–7 |vauthors=Schuermans V, Van Lommel R, Dom J, Brugmans J }}</ref> ] has a different research code: R-58425.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/compound/inspect/CHEMBL2105114 |title=Compound Report Card |access-date=23 June 2016 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160811174542/https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/compound/inspect/CHEMBL2105114 |archive-date=11 August 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| Treatment should be avoided in the presence of high ] or if the stool is bloody (]).<ref name="Butler2008">{{ cite journal | author = Butler, T. | title = Loperamide for the Treatment of Traveler's Diarrhea: Broad or Narrow Usefulness? | journal = Clinical Infectious Diseases | volume = 47 | issue = 8 | pages = 1015–1016 | year = 2008 | month = October | pmid = 18781871 | doi = 10.1086/591704 }}</ref> It is of no value in diarrhea caused by ], ] or ].<ref name="Butler2008"/> Treatment is not recommended for patients that could suffer detrimental effects from rebound ]. If there is a suspicion of diarrhea associated with organisms that can penetrate the intestinal walls, such as ] or ], loperamide is ].<ref>http://www.drugs.com/pro/loperamide.html</ref><ref>http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=0+1303+1459&aid=1432</ref> | |||

| The trial against ] was conducted from December 1972 to February 1974, its results being published in 1977 in the journal ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Mainguet P, Fiasse R | title = Double-blind placebo-controlled study of loperamide (Imodium) in chronic diarrhoea caused by ileocolic disease or resection | journal = Gut | volume = 18 | issue = 7 | pages = 575–9 | date = July 1977 | pmid = 326642 | pmc = 1411573 | doi = 10.1136/gut.18.7.575 | df = dmy }}</ref> | |||

| Loperamide treatment is not used in symptomatic ''C. difficile'' infections, as it increases the risk of toxin retention and precipitation of ]. | |||

| In 1973, Janssen started to promote loperamide under the brand name Imodium. In December 1976, Imodium got ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Set_Current_Drug&ApplNo=017694&DrugName=IMODIUM&ActiveIngred=LOPERAMIDE%20HYDROCHLORIDE&SponsorApplicant=MCNEIL%20CONS&ProductMktStatus=1&goto=Search.DrugDetails|title=IMODIUM FDA Application No.(NDA) 017694|year=1976|publisher=U.S. ] (FDA)|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140813131107/http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails|archive-date=13 August 2014|url-status=dead|access-date=5 September 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Loperamide should be administered with caution to patients suffering from ] due to reduced first pass metabolism.<ref>{{ cite web | title = rxlist.com | year = 2005 | url = http://www.rxlist.com/imodium-drug/indications-dosage.htm }}</ref> | |||

| During the 1980s, Imodium became the best-selling prescription antidiarrheal in the United States.<ref name=court> | |||

| == Adverse effects == | |||

| {{cite court| litigants=McNeil-PPC, Inc., Plaintiff, v. L. Perrigo Company, and Perrigo Company, Defendants| vol=207| reporter=F. Supp. 2d| opinion=356| court=E.D. Pa.| date=25 June 2002| url=http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/207/356/2346092/ <!-- | archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/6SMyfUhOf?url=http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/207/356/2346092/| archive-date=2014-09-05| access-date=2014-09-05 unsupported parameterslast--> }}</ref> | |||

| ]s (ADRs) associated with loperamide include abdominal pain and bloating, nausea, vomiting and constipation. Rare side-effects associated with loperamide are paralytic ileus, dizziness and rashes.<ref name="AustralianMedicine">{{ cite book | title = Australian Medicine Handbook | editor = Bichner, F. | location = Adelaide | publisher = Australian Medicine Handbook Pty Ltd | year = 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| In March 1988, ] began selling loperamide as an ] under the brand name Imodium A-D.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Set_Current_Drug&ApplNo=019487&DrugName=IMODIUM%20A%2DD&ActiveIngred=LOPERAMIDE%20HYDROCHLORIDE&SponsorApplicant=MCNEIL%20CONS&ProductMktStatus=2&goto=Search.DrugDetails|title=IMODIUM A-D FDA Application No.(NDA) 019487|year=1988|publisher=U.S. ] (FDA)|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140813131107/http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails|archive-date=13 August 2014|url-status=dead|access-date=5 September 2014}}</ref> | |||

| === Hepatic === | |||

| It is not recommended for use in ] since it can precipitate ].<ref name="AustralianMedicine" /> | |||

| In the 1980s, loperamide also existed in the form of drops (Imodium Drops) and syrup. Initially, it was intended for children's usage, but ] voluntarily withdrew it from the market in 1990 after 18 cases of ] (resulting in six deaths) were registered in Pakistan and reported by the ] (WHO).<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/index/assoc/h5785e/h5785e.pdf|title=Loperamide: voluntary withdrawal of infant fomulations|year=1990|journal=WHO Drug Information|volume=4|issue=2|pages=73–74|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140907004301/http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/index/assoc/h5785e/h5785e.pdf|archive-date=7 September 2014|url-status=dead|access-date=6 September 2014|quote=The leading international supplier of this preparation, Johnson and Johnson, has since informed WHO that having regard to the dangers inherent in improper use and overdosing, this formulation (Imodium Drops), was voluntarily withdrawn from Pakistan in March 1990. The company has since decided not only to withdraw this preparation worldwide but also to remove all syrup formulations from countries where WHO has a programme for the control of diarrhoeal diseases.}}</ref> In the following years (1990-1991), products containing loperamide have been restricted for children's use in several countries (ranging from two to five years of age).<ref>{{cite book|date=2003|title=Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption And/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted Or Not Approved by Governments, 8th Issue|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=leVCukUgNlsC&pg=PA131|publisher=]|isbn=978-92-1-130230-1|pages=130–131|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170908145128/https://books.google.com/books?id=leVCukUgNlsC&pg=PA131&lpg=PA131&dq=#v=onepage&q&f=true|archive-date=8 September 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ===Marketing in the developing world=== | |||

| In the late 1980s, before the US patent expired on 30 January 1990,<ref name=court/> McNeil started to develop ] containing ] for treating both ] and ]. In March 1997, the company patented this combination.<ref>{{cite patent|country=US|number=5612054|title=Pharmaceutical compositions for treating gastrointestinal distress|gdate=1997-03-18|fdate=1995-04-19|pridate=1989-11-01|invent1=Jeffrey L. Garwin|assign1=McNeil-PPC, Inc.|status=patent}}</ref> The drug was approved in June 1997, by the FDA as Imodium Multi-Symptom Relief in the form of a chewable tablet.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Set_Current_Drug&ApplNo=020606&DrugName=IMODIUM%20MULTI%2DSYMPTOM%20RELIEF&ActiveIngred=LOPERAMIDE%20HYDROCHLORIDE%3B%20SIMETHICONE&SponsorApplicant=MCNEIL&ProductMktStatus=2&goto=Search.DrugDetails|title=IMODIUM MULTI-SYMPTOM RELIEF FDA Application No.(NDA) 020606|year=1997|publisher=U.S. ] (FDA)|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140813131107/http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails|archive-date=13 August 2014|url-status=dead|access-date=5 September 2014}}</ref> A caplet formulation was approved in November 2000.<ref>{{cite web | title=Drug Approval Package: Imodium Advanced (Loperamide HCI and Simethicone NDA #21-140 | website=U.S. ] (FDA) | date=24 December 1999 | url=https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/21-140_Imodium.cfm | access-date=16 December 2020 | archive-date=2 September 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230902195525/https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/21-140_Imodium.cfm | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In ], seven infants died in 1989 and 1990 after parents treated their babies' diarrhea with Imodium, a medicine sold by a subsidiary of ].{{citation needed|date=April 2012}} | |||

| In November 1993, loperamide was launched as an ] based on ] technology.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thefreelibrary.com/SCHERER+ANNOUNCES+LAUNCH+OF+ANOTHER+PRODUCT+UTILIZING+ITS+ZYDIS...-a014279075|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140830174558/http://www.thefreelibrary.com/SCHERER+ANNOUNCES+LAUNCH+OF+ANOTHER+PRODUCT+UTILIZING+ITS+ZYDIS...-a014279075|url-status=dead|archive-date=30 August 2014|title=Scherer announces launch of another product utilizing its Zydis technology|date=9 November 1993|publisher=PR Newswire Association LLC|access-date=30 August 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Rathbone MJ, Hadgraft J, Roberts MS |date=2002|title=Modified-Release Drug Delivery Technology|chapter=The Zydis Oral Fast-Dissolving Dosage Form|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mw9W82MLYZ8C&q=%20janssen&pg=PA200 |publisher=CRC Press|pages = |isbn=9780824708696|access-date=26 August 2014|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/modifiedreleased00mich/page/200}}</ref> | |||

| Since 1980, the World Health Organization has warned doctors of developing countries not to use Imodium because it can paralyze a child's intestines. For months a local doctor begged the company to pull the product from stores, but it didn't do so until a British television program broadcast footage of dying babies.<ref>{{ cite news| url = http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19910609&slug=1288069 | newspaper = The Seattle Times | first = Christopher | last = Scanlan | title = America's Deadly Exports -- Trade Of Toxic Products Abroad Is A Windfall For U.S. Companies | date = 1991-06-09}}</ref> | |||

| In 2013, loperamide in the form of 2-mg tablets was added to the ].<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = ((World Health Organization)) | title = The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2013 (including the 18th WHO model list of essential medicines and the 4th WHO model list of essential medicines for children) | year = 2014 | publisher = World Health Organization | location = Geneva | author-link = World Health Organization | hdl = 10665/112729 | id = WHO technical report series;985 | hdl-access=free | isbn = 9789241209854 | issn = 0512-3054 }}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| In 2020, it was discovered by researchers at ] that Loperamide was effective at killing ] cells.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de/englisch/anti-diarrhoea-drug-drives-cancer-cells-to-cell-death/ |title=Anti-diarrhoea drug drives cancer cells to cell death – Aktuelles aus der Goethe-Universität Frankfurt |website=aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201223113316/https://aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de/englisch/anti-diarrhoea-drug-drives-cancer-cells-to-cell-death/ |archive-date=23 December 2020}}</ref> | |||

| * ] - another opioid medication prescribed for non-analgesic purposes | |||

| * ] - a Mu opioid antagonist (in contrast to the Mu opioid agonist loperamide) that does not cross the blood brain barrier so as to not affect CNS | |||

| ==Society and culture== | |||

| * ] - an anti-gas frequently combined with loperamide in medications | |||

| ===Legal status=== | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==== United States ==== | |||

| * ] | |||

| Loperamide was formerly a ] in the United States. First, it was a ] controlled substance. However, this was lowered to ]. Loperamide was finally removed from control by the ] in 1982, courtesy of then-] ]<ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Mullen F |date=3 November 1982 |title=FR Doc. 82-30264 |url=https://archives.federalregister.gov/issue_slice/1982/11/3/49841-49843.pdf |archive-url=https://archive.today/20230627043028/https://archives.federalregister.gov/issue_slice/1982/11/3/49841-49843.pdf |archive-date=27 June 2023 |access-date=26 June 2023 |website=] |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ====UK==== | |||

| Loperamide can be sold freely to the public by chemists (pharmacies) as the treatment of diarrhoea and acute diarrhoea associated with medically diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome in adults over 18 years of age<ref>{{cite web | url=https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/loperamide-hydrochloride/#:~:text=Loperamide%20can%20be%20sold%20to%20the%20public%2C%20provided,doctor%29%20in%20adults%20over%2018%20years%20of%20age | title=BNF is only available in the UK }}</ref> | |||

| ===Economics=== | |||

| Loperamide is sold as a ].<ref name=AHFS2015/><ref name=Ric2013/> In 2016, Imodium was one of the biggest-selling branded over-the-counter medications sold in Great Britain, with sales of £32.7 million.<ref>{{cite journal | title=A breakdown of the over-the-counter medicines market in Britain in 2016 | journal=The Pharmaceutical Journal | publisher=Royal Pharmaceutical Society | vauthors=Connelly D | date=April 2017 | issn=2053-6186 | doi=10.1211/pj.2017.20202662 | volume=298 | issue=7900 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Brand names=== | |||

| Loperamide was originally marketed as Imodium, and many generic brands are sold.<ref name=Names/> | |||

| ===Off-label/unapproved use=== | |||

| Loperamide has typically been deemed to have a relatively low risk of misuse.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Baker DE | title = Loperamide: a pharmacological review | journal = Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders | volume = 7 | issue = Suppl 3 | pages = S11-8 | date = 2007 | pmid = 18192961 }}</ref> In 2012, no reports of loperamide abuse were made.<ref name=Springer2012>{{cite book|title=Mediators and Drugs in Gastrointestinal Motility II: Endogenous and Exogenous Agents|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d-TrCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA290|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-3-642-68474-6|pages=290–|access-date=18 May 2016|archive-date=12 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230112234947/https://books.google.com/books?id=d-TrCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA290|url-status=live}}</ref> In 2015, however, case reports of extremely high-dose loperamide use were published.<ref name=MacDonaldHeiner2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = MacDonald R, Heiner J, Villarreal J, Strote J | title = Loperamide dependence and abuse | journal = BMJ Case Reports | volume = 2015 | pages = bcr2015209705 | date = May 2015 | pmid = 25935922 | pmc = 4434293 | doi = 10.1136/bcr-2015-209705 }}</ref><ref name=DierksenGonsoulin2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dierksen J, Gonsoulin M, Walterscheid JP | title = Poor Man's Methadone: A Case Report of Loperamide Toxicity | journal = The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology | volume = 36 | issue = 4 | pages = 268–70 | date = December 2015 | pmid = 26355852 | doi = 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000201 | s2cid = 19635919 }}</ref> The primary intent of users has been to manage symptoms of opioid withdrawal such as diarrhea, although a small portion derive psychoactive effects at these higher doses.<ref name=Stan2017/> At these higher doses central nervous system penetration occurs and long-term use may lead to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal on abrupt cessation.<ref name=Stan2017>{{cite journal | vauthors = Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA | title = Loperamide, the "Poor Man's Methadone": Brief Review | journal = Journal of Psychoactive Drugs | volume = 49 | issue = 1 | pages = 18–21 | date = 2017 | pmid = 27918873 | doi = 10.1080/02791072.2016.1260188 | s2cid = 31713818 }}</ref> Dubbing it "the poor man's ]", clinicians warned that increased restrictions on the availability of prescription opioids passed in response to the ] were prompting recreational users to turn to loperamide as an over-the-counter treatment for withdrawal symptoms.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/05/04/physicians-alarmed-by-abuse-of-over-the-counter-diarrhea-medicine-you-know-well/|title=Abuse of diarrhea medicine you know well is alarming physicians|vauthors=Guarino B|date=4 May 2016|newspaper=Washington Post|access-date=6 May 2016|archive-date=6 May 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160506050851/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/05/04/physicians-alarmed-by-abuse-of-over-the-counter-diarrhea-medicine-you-know-well/|url-status=live}}</ref> The FDA responded to these warnings by calling on drug manufacturers to voluntarily limit the package size of loperamide for public-safety reasons.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2018/01/30/fda-wants-to-curb-abuse-of-imodium-the-poor-mans-methadone/|title=FDA wants to curb abuse of Imodium, 'the poor man's methadone'|vauthors=McGinley L|date=30 January 2018|newspaper=Washington Post|access-date=30 January 2018|issn=0190-8286|archive-date=30 January 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180130194140/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2018/01/30/fda-wants-to-curb-abuse-of-imodium-the-poor-mans-methadone/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=FDA2018>{{cite web|author=Office of the Commissioner|title=Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Imodium (loperamide) for Over-the-Counter Use: Drug Safety Communication - FDA Limits Packaging To Encourage Safe Use|url=https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm594403.htm|website=U.S. ] (FDA)|access-date=2 February 2018|archive-date=8 April 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180408052631/https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm594403.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> However, there is no quantity restriction on number of packages that can be purchased, and most pharmacies do not feel capable of restricting its sale, so it is unclear that this intervention will have any impact without further regulation to place loperamide behind the counter.<ref name="Feldman_2020">{{cite journal | vauthors = Feldman R, Everton E | title = National assessment of pharmacist awareness of loperamide abuse and ability to restrict sale if abuse is suspected | journal = Journal of the American Pharmacists Association | volume = 60 | issue = 6 | pages = 868–873 | date = November 2020 | pmid = 32641253 | doi = 10.1016/j.japh.2020.05.021 | s2cid = 220436708 }}</ref> Since 2015, several reports of sometimes-fatal ] due to high-dose loperamide abuse have been published.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Eggleston W, Clark KH, Marraffa JM | title = Loperamide Abuse Associated With Cardiac Dysrhythmia and Death | journal = Annals of Emergency Medicine | volume = 69 | issue = 1 | pages = 83–86 | date = January 2017 | pmid = 27140747 | doi = 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.03.047 }}</ref><ref name="MukarramHindi2016">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mukarram O, Hindi Y, Catalasan G, Ward J | title = Loperamide Induced Torsades de Pointes: A Case Report and Review of the Literature | journal = Case Reports in Medicine | volume = 2016 | pages = 4061980 | year = 2016 | pmid = 26989420 | pmc = 4775784 | doi = 10.1155/2016/4061980 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| {{Antidiarrheals, intestinal anti-inflammatory/anti-infective agents}} | {{Antidiarrheals, intestinal anti-inflammatory/anti-infective agents}} | ||

| {{Opioid receptor modulators}} | |||

| {{Opioids}} | |||

| {{Portal bar | Medicine}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 08:17, 22 December 2024

Medicine used to reduce diarrheaPharmaceutical compound

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /loʊˈpɛrəmaɪd/ |

| Trade names | Imodium, others |

| Other names | R-18553, Loperamide hydrochloride (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682280 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 0.3% |

| Protein binding | 97% |

| Metabolism | Liver (extensive) |

| Elimination half-life | 9–14 hours |

| Excretion | Feces (30–40%), urine (1%) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.053.088 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C29H33ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 477.05 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Loperamide, sold under the brand name Imodium, among others, is a medication of the opioid receptor agonist class used to decrease the frequency of diarrhea. It is often used for this purpose in irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, short bowel syndrome, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis. It is not recommended for those with blood in the stool, mucus in the stool, or fevers. The medication is taken by mouth.

Common side effects include abdominal pain, constipation, sleepiness, vomiting, and dry mouth. It may increase the risk of toxic megacolon. Loperamide's safety in pregnancy is unclear, but no evidence of harm has been found. It appears to be safe in breastfeeding. It is an opioid with no significant absorption from the gut and does not cross the blood–brain barrier when used at normal doses. It works by slowing the contractions of the intestines.

Loperamide was first made in 1969 and used medically in 1976. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. Loperamide is available as a generic medication. In 2022, it was the 297th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 400,000 prescriptions.

Medical uses

Loperamide is effective for the treatment of a number of types of diarrhea. This includes control of acute nonspecific diarrhea, mild traveler's diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic diarrhea due to bowel resection, and chronic diarrhea secondary to inflammatory bowel disease. It is also useful for reducing ileostomy output. Off-label uses for loperamide also include chemotherapy-induced diarrhea, especially related to irinotecan use.

Loperamide should not be used as the primary treatment in cases of bloody diarrhea, acute exacerbation of ulcerative colitis, or bacterial enterocolitis.

Loperamide is often compared to diphenoxylate. Studies suggest that loperamide is more effective and has lower neural side effects.

Side effects

Adverse drug reactions most commonly associated with loperamide are constipation (which occurs in 1.7–5.3% of users), dizziness (up to 1.4%), nausea (0.7–3.2%), and abdominal cramps (0.5–3.0%). Rare, but more serious, side effects include toxic megacolon, paralytic ileus, angioedema, anaphylaxis/allergic reactions, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, urinary retention, and heat stroke. The most frequent symptoms of loperamide overdose are drowsiness, vomiting, and abdominal pain, or burning. High doses may result in heart problems such as abnormal heart rhythms.

Contraindications

Treatment should be avoided in the presence of high fever or if the stool is bloody. Treatment is not recommended for people who could have negative effects from rebound constipation. If suspicion exists of diarrhea associated with organisms that can penetrate the intestinal walls, such as E. coli O157:H7 or Salmonella, loperamide is contraindicated as a primary treatment. Loperamide treatment is not used in symptomatic C. difficile infections, as it increases the risk of toxin retention and precipitation of toxic megacolon.

Loperamide should be administered with caution to people with liver failure due to reduced first-pass metabolism. Additionally, caution should be used when treating people with advanced HIV/AIDS, as cases of both viral and bacterial toxic megacolon have been reported. If abdominal distension is noted, therapy with loperamide should be discontinued.

Children

The use of loperamide in children under two years is not recommended. Rare reports of fatal paralytic ileus associated with abdominal distention have been made. Most of these reports occurred in the setting of acute dysentery, overdose, and with very young children less than two years of age. A review of loperamide in children under 12 years old found that serious adverse events occurred only in children under three years old. The study reported that the use of loperamide should be contraindicated in children who are under 3, systemically ill, malnourished, moderately dehydrated, or have bloody diarrhea.

In 1990, all formulations for children of the antidiarrheal loperamide were banned in Pakistan.

The National Health Service in the United Kingdom recommends that loperamide should only be given to children under the age of twelve if prescribed by a doctor. Formulations for children are only available on prescription in the UK.

Pregnancy and breast feeding

Loperamide is not recommended in the United Kingdom for use during pregnancy or by nursing mothers. Studies in rat models have shown no teratogenicity, but sufficient studies in humans have not been conducted. One controlled, prospective study of 89 women exposed to loperamide during their first trimester of pregnancy showed no increased risk of malformations. This, however, was only one study with a small sample size. Loperamide can be present in breast milk and is not recommended for breastfeeding mothers.

Drug interactions

Loperamide is a substrate of P-glycoprotein; therefore, the concentration of loperamide increases when given with a P-glycoprotein inhibitor. Common P-glycoprotein inhibitors include quinidine, ritonavir, and ketoconazole. Loperamide can decrease the absorption of some other drugs. As an example, saquinavir concentrations can decrease by half when given with loperamide.

Loperamide is an antidiarrheal agent, which decreases intestinal movement. As such, when combined with other antimotility drugs, the risk of constipation is increased. These drugs include other opioids, antihistamines, antipsychotics, and anticholinergics.

Mechanism of action

Loperamide is an opioid-receptor agonist and acts on the μ-opioid receptors in the myenteric plexus of the large intestine. It works like morphine, decreasing the activity of the myenteric plexus, which decreases the tone of the longitudinal and circular smooth muscles of the intestinal wall. This increases the time material stays in the intestine, allowing more water to be absorbed from the fecal matter. It also decreases colonic mass movements and suppresses the gastrocolic reflex.

Loperamide's circulation in the bloodstream is limited in two ways. Efflux by P-glycoprotein in the intestinal wall reduces the passage of loperamide, and the fraction of drug crossing is then further reduced through first-pass metabolism by the liver. Loperamide metabolizes into an MPTP-like compound, but is unlikely to exert neurotoxicity.

Blood–brain barrier

Efflux by P-glycoprotein also prevents circulating loperamide from effectively crossing the blood-brain barrier, so it can generally only antagonize muscarinic receptors in the peripheral nervous system, and currently has a score of one on the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale. Concurrent administration of P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as quinidine potentially allows loperamide to cross the blood-brain barrier and produce central morphine-like effects. At high doses (>70mg), loperamide can saturate P-glycoprotein (thus overcoming the efflux) and produce euphoric effects. Loperamide taken with quinidine was found to produce respiratory depression, indicative of central opioid action.

High doses of loperamide have been shown to cause a mild physical dependence during preclinical studies, specifically in mice, rats, and rhesus monkeys. Symptoms of mild opiate withdrawal were observed following abrupt discontinuation of long-term treatment of animals with loperamide.

Chemistry

Synthesis

Loperamide is synthesized starting from the lactone 3,3-diphenyldihydrofuran-2(3H)-one and ethyl 4-oxopiperidine-1-carboxylate, on a lab scale. On a large scale a similar synthesis is followed, except that the lactone and piperidinone are produced from cheaper materials rather than purchased.

Physical properties

Loperamide is typically manufactured as the hydrochloride salt. Its main polymorph has a melting point of 224 °C and a second polymorph exists with a melting point of 218 °C. A tetrahydrate form has been identified which melts at 190 °C.

History

Loperamide hydrochloride was first synthesized in 1969 by Paul Janssen from Janssen Pharmaceuticals in Beerse, Belgium, following previous discoveries of diphenoxylate hydrochloride (1956) and fentanyl citrate (1960).

The first clinical reports on loperamide were published in 1973 in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry with the inventor being one of the authors. The trial name for it was "R-18553". Loperamide oxide has a different research code: R-58425.

The trial against placebo was conducted from December 1972 to February 1974, its results being published in 1977 in the journal Gut.

In 1973, Janssen started to promote loperamide under the brand name Imodium. In December 1976, Imodium got US FDA approval.

During the 1980s, Imodium became the best-selling prescription antidiarrheal in the United States.

In March 1988, McNeil Pharmaceutical began selling loperamide as an over-the-counter drug under the brand name Imodium A-D.

In the 1980s, loperamide also existed in the form of drops (Imodium Drops) and syrup. Initially, it was intended for children's usage, but Johnson & Johnson voluntarily withdrew it from the market in 1990 after 18 cases of paralytic ileus (resulting in six deaths) were registered in Pakistan and reported by the World Health Organization (WHO). In the following years (1990-1991), products containing loperamide have been restricted for children's use in several countries (ranging from two to five years of age).

In the late 1980s, before the US patent expired on 30 January 1990, McNeil started to develop Imodium Advanced containing loperamide and simethicone for treating both diarrhea and gas. In March 1997, the company patented this combination. The drug was approved in June 1997, by the FDA as Imodium Multi-Symptom Relief in the form of a chewable tablet. A caplet formulation was approved in November 2000.

In November 1993, loperamide was launched as an orally disintegrating tablet based on Zydis technology.

In 2013, loperamide in the form of 2-mg tablets was added to the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines.

In 2020, it was discovered by researchers at Goethe University that Loperamide was effective at killing glioblastoma cells.

Society and culture

Legal status

United States

Loperamide was formerly a controlled substance in the United States. First, it was a Schedule II controlled substance. However, this was lowered to Schedule V. Loperamide was finally removed from control by the Drug Enforcement Administration in 1982, courtesy of then-Administrator Francis M. Mullen Jr.

UK

Loperamide can be sold freely to the public by chemists (pharmacies) as the treatment of diarrhoea and acute diarrhoea associated with medically diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome in adults over 18 years of age

Economics

Loperamide is sold as a generic medication. In 2016, Imodium was one of the biggest-selling branded over-the-counter medications sold in Great Britain, with sales of £32.7 million.

Brand names

Loperamide was originally marketed as Imodium, and many generic brands are sold.

Off-label/unapproved use

Loperamide has typically been deemed to have a relatively low risk of misuse. In 2012, no reports of loperamide abuse were made. In 2015, however, case reports of extremely high-dose loperamide use were published. The primary intent of users has been to manage symptoms of opioid withdrawal such as diarrhea, although a small portion derive psychoactive effects at these higher doses. At these higher doses central nervous system penetration occurs and long-term use may lead to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal on abrupt cessation. Dubbing it "the poor man's methadone", clinicians warned that increased restrictions on the availability of prescription opioids passed in response to the opioid epidemic were prompting recreational users to turn to loperamide as an over-the-counter treatment for withdrawal symptoms. The FDA responded to these warnings by calling on drug manufacturers to voluntarily limit the package size of loperamide for public-safety reasons. However, there is no quantity restriction on number of packages that can be purchased, and most pharmacies do not feel capable of restricting its sale, so it is unclear that this intervention will have any impact without further regulation to place loperamide behind the counter. Since 2015, several reports of sometimes-fatal cardiotoxicity due to high-dose loperamide abuse have been published.

References

- ^ Drugs.com International brands for loperamide Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed 4 September 2015

- Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "Loperamide hydrochloride capsule". DailyMed. 30 September 2022. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "Loperamide Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "About loperamide". nhs.uk. 11 April 2024.

- "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- "Loperamide use while Breastfeeding". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "loperamide hydrochloride". NCI Drug Dictionary. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Patrick GL (2013). An introduction to medicinal chemistry (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 644. ISBN 9780199697397. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ Hamilton RJ (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia (14 ed.). : Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 217. ISBN 9781449673611. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- "Loperamide Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- Hanauer SB (Winter 2008). "The role of loperamide in gastrointestinal disorders". Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders. 8 (1): 15–20. PMID 18477966.

- ^ "Loperamide". Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- Miftahof R (2009). Mathematical Modeling and Simulation in Enteric Neurobiology. World Scientific. p. 18. ISBN 9789812834812. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- Benson A, Chakravarthy A, Hamilton SR, Elin S, eds. (2013). Cancers of the Colon and Rectum: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 225. ISBN 9781936287581. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Zuckerman JN (2012). Principles and Practice of Travel Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. p. 203. ISBN 9781118392089. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Imodium label" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- "loperamide adverse reactions". Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- Litovitz T, Clancy C, Korberly B, Temple AR, Mann KV (1997). "Surveillance of loperamide ingestions: an analysis of 216 poison center reports". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 35 (1): 11–9. doi:10.3109/15563659709001159. PMID 9022646.

- "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Loperamide (Imodium): Drug Safety Communication - Serious Heart Problems With High Doses From Abuse and Misuse". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- "rxlist.com". 2005. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Imodium (Loperamide Hydrochloride) Capsule". DailyMed. NIH. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010.

- Li ST, Grossman DC, Cummings P (2007). "Loperamide therapy for acute diarrhea in children: systematic and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 4 (3): e98. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040098. PMC 1831735. PMID 17388664.

- "E-DRUG: Chlormezanone". Essentialdrugs.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- "Loperamide: a medicine used to treat diarrhoea". National Health Service. 20 December 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- "Medicines information links - NHS Choices". Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- Einarson A, Mastroiacovo P, Arnon J, Ornoy A, Addis A, Malm H, et al. (March 2000). "Prospective, controlled, multicentre study of loperamide in pregnancy". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (3): 185–7. doi:10.1155/2000/957649. PMID 10758415.

- "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Loperamide Drug Interactions - Epocrates Online". online.epocrates.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- "DrugBank: Loperamide". Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Loperamide Hydrochloride Drug Information, Professional". Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- Katzung BG (2004). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (9th ed.). Lange Medical Books/McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-141092-2.

- Lemke TL, Williams DA (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 675. ISBN 9780781768795. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Dufek MB, Knight BM, Bridges AS, Thakker DR (March 2013). "P-glycoprotein increases portal bioavailability of loperamide in mouse by reducing first-pass intestinal metabolism". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 41 (3): 642–50. doi:10.1124/dmd.112.049965. PMID 23288866. S2CID 11014783.

- Kalgutkar AS, Nguyen HT (September 2004). "Identification of an N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-like metabolite of the antidiarrheal agent loperamide in human liver microsomes: underlying reason(s) for the lack of neurotoxicity despite the bioactivation event". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 32 (9): 943–52. PMID 15319335. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Upton RN (August 2007). "Cerebral uptake of drugs in humans". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 34 (8): 695–701. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04649.x. PMID 17600543. S2CID 41591261.

- "Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Antoniou T, Juurlink DN (June 2017). "Loperamide abuse". CMAJ. 189 (23): E803. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161421. PMC 5468105. PMID 28606977.

- Sadeque AJ, Wandel C, He H, Shah S, Wood AJ (September 2000). "Increased drug delivery to the brain by P-glycoprotein inhibition". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 68 (3): 231–7. doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.109156. PMID 11014404. S2CID 38467170.

- Yanagita T, Miyasato K, Sato J (1979). "Dependence potential of loperamide studied in rhesus monkeys". NIDA Research Monograph. 27: 106–13. PMID 121326.

- Nakamura H, Ishii K, Yokoyama Y, Motoyoshi S, Suzuki K, Sekine Y, et al. (November 1982). "[Physical dependence on loperamide hydrochloride in mice and rats]". Yakugaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 102 (11): 1074–85. doi:10.1248/yakushi1947.102.11_1074. PMID 6892112.

- ^ Stokbroekx RA, Vandenberk J, Van Heertum AH, Van Laar GM, Van der Aa MJ, Van Bever WF, et al. (July 1973). "Synthetic antidiarrheal agents. 2,2-Diphenyl-4-(4'-aryl-4'-hydroxypiperidino)butyramides". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (7): 782–786. doi:10.1021/jm00265a009. PMID 4725924.

- US 3714159, Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, issued 1973

- US 3884916, Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, issued 1975

- Van Rompay J, Carter JE (January 1990). Florey K (ed.). "Loperamide hydrochloride". Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances. 19. Academic Press: 341–365. doi:10.1016/s0099-5428(08)60372-x. ISBN 9780122608193.

- Florey K (1991). Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology, Volume 19. Academic Press. p. 342. ISBN 9780080861142. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2016.