This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Keystone18 (talk | contribs) at 04:56, 3 May 2024 (→Withdrawal symptoms and management: ce). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:56, 3 May 2024 by Keystone18 (talk | contribs) (→Withdrawal symptoms and management: ce)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Class of depressant drugs "Benzo" redirects here. For other uses, see Benzo (disambiguation).

| Benzodiazepines | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

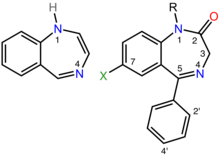

Structural formula of benzodiazepines. Structural formula of benzodiazepines. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Anxiety disorders, seizures, muscle spasms, panic disorder |

| ATC code | N05BA |

| Mode of action | GABAA receptor |

| Clinical data | |

| WebMD | MedicineNet RxList |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D001569 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Benzodiazepines (BZD, BDZ, BZs), colloquially called "benzos", are a class of depressant drugs whose core chemical structure is the fusion of a benzene ring and a diazepine ring. They are prescribed to treat conditions such as anxiety disorders, insomnia, and seizures. The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium), was discovered accidentally by Leo Sternbach in 1955 and was made available in 1960 by Hoffmann–La Roche, which followed with the development of diazepam (Valium) three years later, in 1963. By 1977, benzodiazepines were the most prescribed medications globally; the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), among other factors, decreased rates of prescription, but they remain frequently used worldwide.

Benzodiazepines are depressants that enhance the effect of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at the GABAA receptor, resulting in sedative, hypnotic (sleep-inducing), anxiolytic (anti-anxiety), anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant properties. High doses of many shorter-acting benzodiazepines may also cause anterograde amnesia and dissociation. These properties make benzodiazepines useful in treating anxiety, panic disorder, insomnia, agitation, seizures, muscle spasms, alcohol withdrawal and as a premedication for medical or dental procedures. Benzodiazepines are categorized as short, intermediate, or long-acting. Short- and intermediate-acting benzodiazepines are preferred for the treatment of insomnia; longer-acting benzodiazepines are recommended for the treatment of anxiety.

Benzodiazepines are generally viewed as safe and effective for short-term use of two to four weeks, although cognitive impairment and paradoxical effects such as aggression or behavioral disinhibition can occur. According to the Government of Victoria's Department of Health, long-term use can cause "impaired thinking or memory loss, anxiety and depression, irritability, paranoia, aggression, etc." A minority of people have paradoxical reactions after taking benzodiazepines such as worsened agitation or panic.

Benzodiazepines are associated with an increased risk of suicide due to aggression, impulsivity, and negative withdrawal effects. Long-term use is controversial because of concerns about decreasing effectiveness, physical dependence, benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, and an increased risk of dementia and cancer. The elderly are at an increased risk of both short- and long-term adverse effects, and as a result, all benzodiazepines are listed in the Beers List of inappropriate medications for older adults. There is controversy concerning the safety of benzodiazepines in pregnancy. While they are not major teratogens, uncertainty remains as to whether they cause cleft palate in a small number of babies and whether neurobehavioural effects occur as a result of prenatal exposure; they are known to cause withdrawal symptoms in the newborn.

In an overdose, benzodiazepines can cause dangerous deep unconsciousness, but are less toxic than their predecessors, the barbiturates, and death rarely results when a benzodiazepine is the only drug taken. Combined with other central nervous system (CNS) depressants such as alcohol and opioids, the potential for toxicity and fatal overdose increases significantly. Benzodiazepines are commonly used recreationally and also often taken in combination with other addictive substances, and are controlled in most countries.

Medical uses

See also: List of benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines possess psycholeptic, sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, muscle relaxant, and amnesic actions, which are useful in a variety of indications such as alcohol dependence, seizures, anxiety disorders, panic, agitation, and insomnia. Most are administered orally; however, they can also be given intravenously, intramuscularly, or rectally. In general, benzodiazepines are well tolerated and are safe and effective drugs in the short term for a wide range of conditions. Tolerance can develop to their effects and there is also a risk of dependence, and upon discontinuation a withdrawal syndrome may occur. These factors, combined with other possible secondary effects after prolonged use such as psychomotor, cognitive, or memory impairments, limit their long-term applicability. The effects of long-term use or misuse include the tendency to cause or worsen cognitive deficits, depression, and anxiety. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia recommends discontinuing the usage of benzodiazepines in those on opioids and those who have used them long term. Benzodiazepines can have serious adverse health outcomes, and these findings support clinical and regulatory efforts to reduce usage, especially in combination with non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists.

Panic disorder

Further information: Panic disorderBecause of their effectiveness, tolerability, and rapid onset of anxiolytic action, benzodiazepines are frequently used for the treatment of anxiety associated with panic disorder. However, there is disagreement among expert bodies regarding the long-term use of benzodiazepines for panic disorder. The views range from those holding benzodiazepines are not effective long-term and should be reserved for treatment-resistant cases to those holding they are as effective in the long term as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines, published in January 2009, note that, in general, benzodiazepines are well tolerated, and their use for the initial treatment for panic disorder is strongly supported by numerous controlled trials. APA states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend any of the established panic disorder treatments over another. The choice of treatment between benzodiazepines, SSRIs, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and psychotherapy should be based on the patient's history, preference, and other individual characteristics. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are likely to be the best choice of pharmacotherapy for many patients with panic disorder, but benzodiazepines are also often used, and some studies suggest that these medications are still used with greater frequency than the SSRIs. One advantage of benzodiazepines is that they alleviate the anxiety symptoms much faster than antidepressants, and therefore may be preferred in patients for whom rapid symptom control is critical. However, this advantage is offset by the possibility of developing benzodiazepine dependence. APA does not recommend benzodiazepines for persons with depressive symptoms or a recent history of substance use disorder. APA guidelines state that, in general, pharmacotherapy of panic disorder should be continued for at least a year, and that clinical experience supports continuing benzodiazepine treatment to prevent recurrence. Although major concerns about benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal have been raised, there is no evidence for significant dose escalation in patients using benzodiazepines long-term. For many such patients, stable doses of benzodiazepines retain their efficacy over several years.

Guidelines issued by the UK-based National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), carried out a systematic review using different methodology and came to a different conclusion. They questioned the accuracy of studies that were not placebo-controlled. And, based on the findings of placebo-controlled studies, they do not recommend use of benzodiazepines beyond two to four weeks, as tolerance and physical dependence develop rapidly, with withdrawal symptoms including rebound anxiety occurring after six weeks or more of use. Nevertheless, benzodiazepines are still prescribed for long-term treatment of anxiety disorders, although specific antidepressants and psychological therapies are recommended as the first-line treatment options with the anticonvulsant drug pregabalin indicated as a second- or third-line treatment and suitable for long-term use. NICE stated that long-term use of benzodiazepines for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia is an unlicensed indication, does not have long-term efficacy, and is, therefore, not recommended by clinical guidelines. Psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy are recommended as a first-line therapy for panic disorder; benzodiazepine use has been found to interfere with therapeutic gains from these therapies.

Benzodiazepines are usually administered orally; however, very occasionally lorazepam or diazepam may be given intravenously for the treatment of panic attacks.

Generalized anxiety disorder

Further information: Generalized anxiety disorderBenzodiazepines have robust efficacy in the short-term management of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), but were not shown effective in producing long-term improvement overall. According to National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), benzodiazepines can be used in the immediate management of GAD, if necessary. However, they should not usually be given for longer than 2–4 weeks. The only medications NICE recommends for the longer term management of GAD are antidepressants.

Likewise, Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA) recommends benzodiazepines alprazolam, bromazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam only as a second-line choice, if the treatment with two different antidepressants was unsuccessful. Although they are second-line agents, benzodiazepines can be used for a limited time to relieve severe anxiety and agitation. CPA guidelines note that after 4–6 weeks the effect of benzodiazepines may decrease to the level of placebo, and that benzodiazepines are less effective than antidepressants in alleviating ruminative worry, the core symptom of GAD. However, in some cases, a prolonged treatment with benzodiazepines as the add-on to an antidepressant may be justified.

A 2015 review found a larger effect with medications than talk therapy. Medications with benefit include serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Anxiety

Further information: Panic attackBenzodiazepines are sometimes used in the treatment of acute anxiety, since they result in rapid and marked relief of symptoms in most individuals; however, they are not recommended beyond 2–4 weeks of use due to risks of tolerance and dependence and a lack of long-term effectiveness. As for insomnia, they may also be used on an irregular/"as-needed" basis, such as in cases where said anxiety is at its worst. Compared to other pharmacological treatments, benzodiazepines are twice as likely to lead to a relapse of the underlying condition upon discontinuation. Psychological therapies and other pharmacological therapies are recommended for the long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Antidepressants have higher remission rates and are, in general, safe and effective in the short and long term.

Insomnia

Further information: Insomnia

Benzodiazepines can be useful for short-term treatment of insomnia. Their use beyond 2 to 4 weeks is not recommended due to the risk of dependence. The Committee on Safety of Medicines report recommended that where long-term use of benzodiazepines for insomnia is indicated then treatment should be intermittent wherever possible. It is preferred that benzodiazepines be taken intermittently and at the lowest effective dose. They improve sleep-related problems by shortening the time spent in bed before falling asleep, prolonging the sleep time, and, in general, reducing wakefulness. However, they worsen sleep quality by increasing light sleep and decreasing deep sleep. Other drawbacks of hypnotics, including benzodiazepines, are possible tolerance to their effects, rebound insomnia, and reduced slow-wave sleep and a withdrawal period typified by rebound insomnia and a prolonged period of anxiety and agitation.

The list of benzodiazepines approved for the treatment of insomnia is fairly similar among most countries, but which benzodiazepines are officially designated as first-line hypnotics prescribed for the treatment of insomnia varies between countries. Longer-acting benzodiazepines such as nitrazepam and diazepam have residual effects that may persist into the next day and are, in general, not recommended.

Since the release of nonbenzodiazepines, also known as z-drugs, in 1992 in response to safety concerns, individuals with insomnia and other sleep disorders have increasingly been prescribed nonbenzodiazepines (2.3% in 1993 to 13.7% of Americans in 2010), less often prescribed benzodiazepines (23.5% in 1993 to 10.8% in 2010). It is not clear as to whether the new non benzodiazepine hypnotics (Z-drugs) are better than the short-acting benzodiazepines. The efficacy of these two groups of medications is similar. According to the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, indirect comparison indicates that side-effects from benzodiazepines may be about twice as frequent as from nonbenzodiazepines. Some experts suggest using nonbenzodiazepines preferentially as a first-line long-term treatment of insomnia. However, the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence did not find any convincing evidence in favor of Z-drugs. NICE review pointed out that short-acting Z-drugs were inappropriately compared in clinical trials with long-acting benzodiazepines. There have been no trials comparing short-acting Z-drugs with appropriate doses of short-acting benzodiazepines. Based on this, NICE recommended choosing the hypnotic based on cost and the patient's preference.

Older adults should not use benzodiazepines to treat insomnia unless other treatments have failed. When benzodiazepines are used, patients, their caretakers, and their physician should discuss the increased risk of harms, including evidence that shows twice the incidence of traffic collisions among driving patients, and falls and hip fracture for older patients.

Seizures

Further information: SeizureProlonged convulsive epileptic seizures are a medical emergency that can usually be dealt with effectively by administering fast-acting benzodiazepines, which are potent anticonvulsants. In a hospital environment, intravenous clonazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam are first-line choices. In the community, intravenous administration is not practical and so rectal diazepam or buccal midazolam are used, with a preference for midazolam as its administration is easier and more socially acceptable.

When benzodiazepines were first introduced, they were enthusiastically adopted for treating all forms of epilepsy. However, drowsiness and tolerance become problems with continued use and none are now considered first-line choices for long-term epilepsy therapy. Clobazam is widely used by specialist epilepsy clinics worldwide and clonazepam is popular in the Netherlands, Belgium and France. Clobazam was approved for use in the United States in 2011. In the UK, both clobazam and clonazepam are second-line choices for treating many forms of epilepsy. Clobazam also has a useful role for very short-term seizure prophylaxis and in catamenial epilepsy. Discontinuation after long-term use in epilepsy requires additional caution because of the risks of rebound seizures. Therefore, the dose is slowly tapered over a period of up to six months or longer.

Alcohol withdrawal

Further information: Alcohol detoxificationChlordiazepoxide is the most commonly used benzodiazepine for alcohol detoxification, but diazepam may be used as an alternative. Both are used in the detoxification of individuals who are motivated to stop drinking, and are prescribed for a short period of time to reduce the risks of developing tolerance and dependence to the benzodiazepine medication itself. The benzodiazepines with a longer half-life make detoxification more tolerable, and dangerous (and potentially lethal) alcohol withdrawal effects are less likely to occur. On the other hand, short-acting benzodiazepines may lead to breakthrough seizures, and are, therefore, not recommended for detoxification in an outpatient setting. Oxazepam and lorazepam are often used in patients at risk of drug accumulation, in particular, the elderly and those with cirrhosis, because they are metabolized differently from other benzodiazepines, through conjugation.

Benzodiazepines are the preferred choice in the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, in particular, for the prevention and treatment of the dangerous complication of seizures and in subduing severe delirium. Lorazepam is the only benzodiazepine with predictable intramuscular absorption and it is the most effective in preventing and controlling acute seizures.

Other indications

Benzodiazepines are often prescribed for a wide range of conditions:

- They can sedate patients receiving mechanical ventilation or those in extreme distress. Caution is exercised in this situation due to the risk of respiratory depression, and it is recommended that benzodiazepine overdose treatment facilities should be available. They have also been found to increase the likelihood of later PTSD after people have been removed from ventilators.

- Benzodiazepines are indicated in the management of breathlessness (shortness of breath) in advanced diseases, in particular where other treatments have failed to adequately control symptoms.

- Benzodiazepines are effective as medication given a couple of hours before surgery to relieve anxiety. They also produce amnesia, which can be useful, as patients may not remember unpleasantness from the procedure. They are also used in patients with dental phobia as well as some ophthalmic procedures like refractive surgery; although such use is controversial and only recommended for those who are very anxious. Midazolam is the most commonly prescribed for this use because of its strong sedative actions and fast recovery time, as well as its water solubility, which reduces pain upon injection. Diazepam and lorazepam are sometimes used. Lorazepam has particularly marked amnesic properties that may make it more effective when amnesia is the desired effect.

- Benzodiazepines are well known for their strong muscle-relaxing properties and can be useful in the treatment of muscle spasms, although tolerance often develops to their muscle relaxant effects. Baclofen or tizanidine are sometimes used as an alternative to benzodiazepines. Tizanidine has been found to have superior tolerability compared to diazepam and baclofen.

- Benzodiazepines are also used to treat the acute panic caused by hallucinogen intoxication. Benzodiazepines are also used to calm the acutely agitated individual and can, if required, be given via an intramuscular injection. They can sometimes be effective in the short-term treatment of psychiatric emergencies such as acute psychosis as in schizophrenia or mania, bringing about rapid tranquillization and sedation until the effects of lithium or neuroleptics (antipsychotics) take effect. Lorazepam is most commonly used but clonazepam is sometimes prescribed for acute psychosis or mania; their long-term use is not recommended due to risks of dependence. Further research investigating the use of benzodiazepines alone and in combination with antipsychotic medications for treating acute psychosis is warranted.

- Clonazepam, a benzodiazepine is used to treat many forms of parasomnia. Rapid eye movement behavior disorder responds well to low doses of clonazepam. Restless legs syndrome can be treated using clonazepam as a third line treatment option as the use of clonazepam is still investigational.

- Benzodiazepines are sometimes used for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), although they are generally believed ineffective for this indication. Effectiveness was, however, found in one small study. Benzodiazepines can be considered as a treatment option in treatment resistant cases.

- Antipsychotics are generally a first-line treatment for delirium; however, when delirium is caused by alcohol or sedative hypnotic withdrawal, benzodiazepines are a first-line treatment.

- There is some evidence that low doses of benzodiazepines reduce adverse effects of electroconvulsive therapy.

Contraindications

Because of their muscle relaxant action, benzodiazepines may cause respiratory depression in susceptible individuals. For that reason, they are contraindicated in people with myasthenia gravis, sleep apnea, bronchitis, and COPD. Caution is required when benzodiazepines are used in people with personality disorders or intellectual disability because of frequent paradoxical reactions. In major depression, they may precipitate suicidal tendencies and are sometimes used for suicidal overdoses. Individuals with a history of excessive alcohol use or non-medical use of opioids or barbiturates should avoid benzodiazepines, as there is a risk of life-threatening interactions with these drugs.

Pregnancy

See also: Effects of benzodiazepines on newbornsIn the United States, the Food and Drug Administration has categorized benzodiazepines into either category D or X meaning potential for harm in the unborn has been demonstrated.

Exposure to benzodiazepines during pregnancy has been associated with a slightly increased (from 0.06 to 0.07%) risk of cleft palate in newborns, a controversial conclusion as some studies find no association between benzodiazepines and cleft palate. Their use by expectant mothers shortly before the delivery may result in a floppy infant syndrome. Newborns with this condition tend to have hypotonia, hypothermia, lethargy, and breathing and feeding difficulties. Cases of neonatal withdrawal syndrome have been described in infants chronically exposed to benzodiazepines in utero. This syndrome may be hard to recognize, as it starts several days after delivery, for example, as late as 21 days for chlordiazepoxide. The symptoms include tremors, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, hyperactivity, and vomiting and may last for up to three to six months. Tapering down the dose during pregnancy may lessen its severity. If used in pregnancy, those benzodiazepines with a better and longer safety record, such as diazepam or chlordiazepoxide, are recommended over potentially more harmful benzodiazepines, such as temazepam or triazolam. Using the lowest effective dose for the shortest period of time minimizes the risks to the unborn child.

Elderly

The benefits of benzodiazepines are least and the risks are greatest in the elderly. They are listed as a potentially inappropriate medication for older adults by the American Geriatrics Society. The elderly are at an increased risk of dependence and are more sensitive to the adverse effects such as memory problems, daytime sedation, impaired motor coordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls, and an increased risk of hip fractures. The long-term effects of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine dependence in the elderly can resemble dementia, depression, or anxiety syndromes, and progressively worsens over time. Adverse effects on cognition can be mistaken for the effects of old age. The benefits of withdrawal include improved cognition, alertness, mobility, reduced risk incontinence, and a reduced risk of falls and fractures. The success of gradual-tapering benzodiazepines is as great in the elderly as in younger people. Benzodiazepines should be prescribed to the elderly only with caution and only for a short period at low doses. Short to intermediate-acting benzodiazepines are preferred in the elderly such as oxazepam and temazepam. The high potency benzodiazepines alprazolam and triazolam and long-acting benzodiazepines are not recommended in the elderly due to increased adverse effects. Nonbenzodiazepines such as zaleplon and zolpidem and low doses of sedating antidepressants are sometimes used as alternatives to benzodiazepines.

Long-term use of benzodiazepines is associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia, and reduction in prescribing levels is likely to reduce dementia risk. The association of a history of benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline is unclear, with some studies reporting a lower risk of cognitive decline in former users, some finding no association and some indicating an increased risk of cognitive decline.

Benzodiazepines are sometimes prescribed to treat behavioral symptoms of dementia. However, like antidepressants, they have little evidence of effectiveness, although antipsychotics have shown some benefit. Cognitive impairing effects of benzodiazepines that occur frequently in the elderly can also worsen dementia.

Adverse effects

See also: Long-term effects of benzodiazepines, Paradoxical reaction § Benzodiazepines, and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndromeThe most common side-effects of benzodiazepines are related to their sedating and muscle-relaxing action. They include drowsiness, dizziness, and decreased alertness and concentration. Lack of coordination may result in falls and injuries particularly in the elderly. Another result is impairment of driving skills and increased likelihood of road traffic accidents. Decreased libido and erection problems are a common side effect. Depression and disinhibition may emerge. Hypotension and suppressed breathing (hypoventilation) may be encountered with intravenous use. Less common side effects include nausea and changes in appetite, blurred vision, confusion, euphoria, depersonalization and nightmares. Cases of liver toxicity have been described but are very rare.

The long-term effects of benzodiazepine use can include cognitive impairment as well as affective and behavioural problems. Feelings of turmoil, difficulty in thinking constructively, loss of sex-drive, agoraphobia and social phobia, increasing anxiety and depression, loss of interest in leisure pursuits and interests, and an inability to experience or express feelings can also occur. Not everyone, however, experiences problems with long-term use. Additionally, an altered perception of self, environment and relationships may occur. A study published in 2020 found that long-term use of prescription benzodiazepines is associated with an increase in all-cause mortality among those age 65 or younger, but not those older than 65. The study also found that all-cause mortality was increased further in cases in which benzodiazepines are co-prescribed with opioids, relative to cases in which benzodiazepines are prescribed without opioids, but again only in those age 65 or younger.

Compared to other sedative-hypnotics, visits to the hospital involving benzodiazepines had a 66% greater odds of a serious adverse health outcome. This included hospitalization, patient transfer, or death, and visits involving a combination of benzodiazepines and non-benzodiapine receptor agonists had almost four-times increased odds of a serious health outcome.

In September 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the boxed warning be updated for all benzodiazepine medicines to describe the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions consistently across all the medicines in the class.

Cognitive effects

The short-term use of benzodiazepines adversely affects multiple areas of cognition, the most notable one being that it interferes with the formation and consolidation of memories of new material and may induce complete anterograde amnesia. However, researchers hold contrary opinions regarding the effects of long-term administration. One view is that many of the short-term effects continue into the long-term and may even worsen, and are not resolved after stopping benzodiazepine usage. Another view maintains that cognitive deficits in chronic benzodiazepine users occur only for a short period after the dose, or that the anxiety disorder is the cause of these deficits.

While the definitive studies are lacking, the former view received support from a 2004 meta-analysis of 13 small studies. This meta-analysis found that long-term use of benzodiazepines was associated with moderate to large adverse effects on all areas of cognition, with visuospatial memory being the most commonly detected impairment. Some of the other impairments reported were decreased IQ, visiomotor coordination, information processing, verbal learning and concentration. The authors of the meta-analysis and a later reviewer noted that the applicability of this meta-analysis is limited because the subjects were taken mostly from withdrawal clinics; the coexisting drug, alcohol use, and psychiatric disorders were not defined; and several of the included studies conducted the cognitive measurements during the withdrawal period.

Paradoxical effects

Paradoxical reactions, such as increased seizures in epileptics, aggression, violence, impulsivity, irritability and suicidal behavior sometimes occur. These reactions have been explained as consequences of disinhibition and the subsequent loss of control over socially unacceptable behavior. Paradoxical reactions are rare in the general population, with an incidence rate below 1% and similar to placebo. However, they occur with greater frequency in recreational abusers, individuals with borderline personality disorder, children, and patients on high-dosage regimes. In these groups, impulse control problems are perhaps the most important risk factor for disinhibition; learning disabilities and neurological disorders are also significant risks. Most reports of disinhibition involve high doses of high-potency benzodiazepines. Paradoxical effects may also appear after chronic use of benzodiazepines.

Long-term worsening of psychiatric symptoms

While benzodiazepines may have short-term benefits for anxiety, sleep and agitation in some patients, long-term (i.e., greater than 2–4 weeks) use can result in a worsening of the very symptoms the medications are meant to treat. Potential explanations include exacerbating cognitive problems that are already common in anxiety disorders, causing or worsening depression and suicidality, disrupting sleep architecture by inhibiting deep stage sleep, withdrawal symptoms or rebound symptoms in between doses mimicking or exacerbating underlying anxiety or sleep disorders, inhibiting the benefits of psychotherapy by inhibiting memory consolidation and reducing fear extinction, and reducing coping with trauma/stress and increasing vulnerability to future stress. The latter two explanations may be why benzodiazepines are ineffective and/or potentially harmful in PTSD and phobias. Anxiety, insomnia and irritability may be temporarily exacerbated during withdrawal, but psychiatric symptoms after discontinuation are usually less than even while taking benzodiazepines. Functioning significantly improves within 1 year of discontinuation.

Physical dependence, withdrawal and post-withdrawal syndromes

Tolerance

The main problem of the chronic use of benzodiazepines is the development of tolerance and dependence. Tolerance manifests itself as diminished pharmacological effect and develops relatively quickly to the sedative, hypnotic, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant actions of benzodiazepines. Tolerance to anti-anxiety effects develops more slowly with little evidence of continued effectiveness beyond four to six months of continued use. In general, tolerance to the amnesic effects does not occur. However, controversy exists as to tolerance to the anxiolytic effects with some evidence that benzodiazepines retain efficacy and opposing evidence from a systematic review of the literature that tolerance frequently occurs and some evidence that anxiety may worsen with long-term use. The question of tolerance to the amnesic effects of benzodiazepines is, likewise, unclear. Some evidence suggests that partial tolerance does develop, and that, "memory impairment is limited to a narrow window within 90 minutes after each dose".

A major disadvantage of benzodiazepines is that tolerance to therapeutic effects develops relatively quickly while many adverse effects persist. Tolerance develops to hypnotic and myorelaxant effects within days to weeks, and to anticonvulsant and anxiolytic effects within weeks to months. Therefore, benzodiazepines are unlikely to be effective long-term treatments for sleep and anxiety. While BZD therapeutic effects disappear with tolerance, depression and impulsivity with high suicidal risk commonly persist. Several studies have confirmed that long-term benzodiazepines are not significantly different from placebo for sleep or anxiety. This may explain why patients commonly increase doses over time and many eventually take more than one type of benzodiazepine after the first loses effectiveness. Additionally, because tolerance to benzodiazepine sedating effects develops more quickly than does tolerance to brainstem depressant effects, those taking more benzodiazepines to achieve desired effects may experience sudden respiratory depression, hypotension or death. Most patients with anxiety disorders and PTSD have symptoms that persist for at least several months, making tolerance to therapeutic effects a distinct problem for them and necessitating the need for more effective long-term treatment (e.g., psychotherapy, serotonergic antidepressants).

Withdrawal symptoms and management

Discontinuation of benzodiazepines or abrupt reduction of the dose, even after a relatively short course of treatment (two to four weeks), may result in two groups of symptoms, rebound and withdrawal. Rebound symptoms are the return of the symptoms for which the patient was treated but worse than before. Withdrawal symptoms are the new symptoms that occur when the benzodiazepine is stopped. They are the main sign of physical dependence.

The most frequent symptoms of withdrawal from benzodiazepines are insomnia, gastric problems, tremors, agitation, fearfulness, and muscle spasms. The less frequent effects are irritability, sweating, depersonalization, derealization, hypersensitivity to stimuli, depression, suicidal behavior, psychosis, seizures, and delirium tremens. Severe symptoms usually occur as a result of abrupt or over-rapid withdrawal. Abrupt withdrawal can be dangerous and lead to excitotoxicity, causing damage and even death to nerve cells as a result of excessive levels of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate. Increased glutamatergic activity is thought to be part of a compensatory mechanism to chronic GABAergic inhibition from benzodiazepines. Therefore, a gradual reduction regimen is recommended.

Symptoms may also occur during a gradual dosage reduction, but are typically less severe and may persist as part of a protracted withdrawal syndrome for months after cessation of benzodiazepines. Approximately 10% of patients experience a notable protracted withdrawal syndrome, which can persist for many months or in some cases a year or longer. Protracted symptoms tend to resemble those seen during the first couple of months of withdrawal but usually are of a sub-acute level of severity. Such symptoms do gradually lessen over time, eventually disappearing altogether.

Benzodiazepines have a reputation with patients and doctors for causing a severe and traumatic withdrawal; however, this is in large part due to the withdrawal process being poorly managed. Over-rapid withdrawal from benzodiazepines increases the severity of the withdrawal syndrome and increases the failure rate. A slow and gradual withdrawal customised to the individual and, if indicated, psychological support is the most effective way of managing the withdrawal. Opinion as to the time needed to complete withdrawal ranges from four weeks to several years. A goal of less than six months has been suggested, but due to factors such as dosage and type of benzodiazepine, reasons for prescription, lifestyle, personality, environmental stresses, and amount of available support, a year or more may be needed to withdraw.

Withdrawal is best managed by transferring the physically dependent patient to an equivalent dose of diazepam because it has the longest half-life of all of the benzodiazepines, is metabolised into long-acting active metabolites and is available in low-potency tablets, which can be quartered for smaller doses. A further benefit is that it is available in liquid form, which allows for even smaller reductions. Chlordiazepoxide, which also has a long half-life and long-acting active metabolites, can be used as an alternative.

Nonbenzodiazepines are contraindicated during benzodiazepine withdrawal as they are cross tolerant with benzodiazepines and can induce dependence. Alcohol is also cross tolerant with benzodiazepines and more toxic and thus caution is needed to avoid replacing one dependence with another. During withdrawal, fluoroquinolone-based antibiotics are best avoided if possible; they displace benzodiazepines from their binding site and reduce GABA function and, thus, may aggravate withdrawal symptoms. Antipsychotics are not recommended for benzodiazepine withdrawal (or other CNS depressant withdrawal states) especially clozapine, olanzapine or low potency phenothiazines, e.g., chlorpromazine as they lower the seizure threshold and can worsen withdrawal effects; if used extreme caution is required.

Withdrawal from long term benzodiazepines is beneficial for most individuals. Withdrawal of benzodiazepines from long-term users, in general, leads to improved physical and mental health particularly in the elderly; although some long term users report continued benefit from taking benzodiazepines, this may be the result of suppression of withdrawal effects.

Controversial associations

Beyond the well established link between benzodiazepines and psychomotor impairment resulting in motor vehicle accidents and falls leading to fracture; research in the 2000s and 2010s has raised the association between benzodiazepines (and Z-drugs) and other, as of yet unproven, adverse effects including dementia, cancer, infections, pancreatitis and respiratory disease exacerbations.

Dementia

A number of studies have drawn an association between long-term benzodiazepine use and neuro-degenerative disease, particularly Alzheimer's disease. It has been determined that long-term use of benzodiazepines is associated with increased dementia risk, even after controlling for protopathic bias.

Infections

Some observational studies have detected significant associations between benzodiazepines and respiratory infections such as pneumonia where others have not. A large meta-analysis of pre-marketing randomized controlled trials on the pharmacologically related Z-Drugs suggest a small increase in infection risk as well. An immunodeficiency effect from the action of benzodiazepines on GABA-A receptors has been postulated from animal studies.

Cancer

A meta-analysis of observational studies has determined an association between benzodiazepine use and cancer, though the risk across different agents and different cancers varied significantly. In terms of experimental basic science evidence, an analysis of carcinogenetic and genotoxicity data for various benzodiazepines has suggested a small possibility of carcinogenesis for a small number of benzodiazepines.

Pancreatitis

The evidence suggesting a link between benzodiazepines (and Z-Drugs) and pancreatic inflammation is very sparse and limited to a few observational studies from Taiwan. A criticism of confounding can be applied to these findings as with the other controversial associations above. Further well-designed research from other populations as well as a biologically plausible mechanism is required to confirm this association.

Overdose

Main article: Benzodiazepine overdoseAlthough benzodiazepines are much safer in overdose than their predecessors, the barbiturates, they can still cause problems in overdose. Taken alone, they rarely cause severe complications in overdose; statistics in England showed that benzodiazepines were responsible for 3.8% of all deaths by poisoning from a single drug. However, combining these drugs with alcohol, opiates or tricyclic antidepressants markedly raises the toxicity. The elderly are more sensitive to the side effects of benzodiazepines, and poisoning may even occur from their long-term use. The various benzodiazepines differ in their toxicity; temazepam appears most toxic in overdose and when used with other drugs. The symptoms of a benzodiazepine overdose may include; drowsiness, slurred speech, nystagmus, hypotension, ataxia, coma, respiratory depression, and cardiorespiratory arrest.

A reversal agent for benzodiazepines exists, flumazenil (Anexate). Its use as an antidote is not routinely recommended because of the high risk of resedation and seizures. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 326 people, 4 people had serious adverse events and 61% became resedated following the use of flumazenil. Numerous contraindications to its use exist. It is contraindicated in people with a history of long-term use of benzodiazepines, those having ingested a substance that lowers the seizure threshold or may cause an arrhythmia, and in those with abnormal vital signs. One study found that only 10% of the people presenting with a benzodiazepine overdose are suitable candidates for treatment with flumazenil.

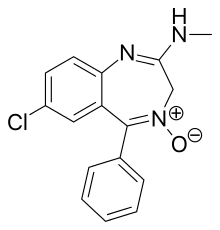

Left: US yearly overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines. Center: The top line represents the number of benzodiazepine deaths that also involved opioids in the US. The bottom line represents benzodiazepine deaths that did not involve opioids. Right: Chemical structure of the benzodiazepine flumazenil, whose use is controversial following benzodiazepine overdose.

Left: US yearly overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines. Center: The top line represents the number of benzodiazepine deaths that also involved opioids in the US. The bottom line represents benzodiazepine deaths that did not involve opioids. Right: Chemical structure of the benzodiazepine flumazenil, whose use is controversial following benzodiazepine overdose.

Interactions

Individual benzodiazepines may have different interactions with certain drugs. Depending on their metabolism pathway, benzodiazepines can be divided roughly into two groups. The largest group consists of those that are metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes and possess significant potential for interactions with other drugs. The other group comprises those that are metabolized through glucuronidation, such as lorazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam, and, in general, have few drug interactions.

Many drugs, including oral contraceptives, some antibiotics, antidepressants, and antifungal agents, inhibit cytochrome enzymes in the liver. They reduce the rate of elimination of the benzodiazepines that are metabolized by CYP450, leading to possibly excessive drug accumulation and increased side-effects. In contrast, drugs that induce cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as St John's wort, the antibiotic rifampicin, and the anticonvulsants carbamazepine and phenytoin, accelerate elimination of many benzodiazepines and decrease their action. Taking benzodiazepines with alcohol, opioids and other central nervous system depressants potentiates their action. This often results in increased sedation, impaired motor coordination, suppressed breathing, and other adverse effects that have potential to be lethal. Antacids can slow down absorption of some benzodiazepines; however, this effect is marginal and inconsistent.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Benzodiazepines work by increasing the effectiveness of the endogenous chemical, GABA, to decrease the excitability of neurons. This reduces the communication between neurons and, therefore, has a calming effect on many of the functions of the brain.

GABA controls the excitability of neurons by binding to the GABAA receptor. The GABAA receptor is a protein complex located in the synapses between neurons. All GABAA receptors contain an ion channel that conducts chloride ions across neuronal cell membranes and two binding sites for the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), while a subset of GABAA receptor complexes also contain a single binding site for benzodiazepines. Binding of benzodiazepines to this receptor complex does not alter binding of GABA. Unlike other positive allosteric modulators that increase ligand binding, benzodiazepine binding acts as a positive allosteric modulator by increasing the total conduction of chloride ions across the neuronal cell membrane when GABA is already bound to its receptor. This increased chloride ion influx hyperpolarizes the neuron's membrane potential. As a result, the difference between resting potential and threshold potential is increased and firing is less likely. Different GABAA receptor subtypes have varying distributions within different regions of the brain and, therefore, control distinct neuronal circuits. Hence, activation of different GABAA receptor subtypes by benzodiazepines may result in distinct pharmacological actions. In terms of the mechanism of action of benzodiazepines, their similarities are too great to separate them into individual categories such as anxiolytic or hypnotic. For example, a hypnotic administered in low doses produces anxiety-relieving effects, whereas a benzodiazepine marketed as an anti-anxiety drug at higher doses induces sleep.

The subset of GABAA receptors that also bind benzodiazepines are referred to as benzodiazepine receptors (BzR). The GABAA receptor is a heteromer composed of five subunits, the most common ones being two αs, two βs, and one γ (α2β2γ1). For each subunit, many subtypes exist (α1–6, β1–3, and γ1–3). GABAA receptors that are made up of different combinations of subunit subtypes have different properties, different distributions in the brain and different activities relative to pharmacological and clinical effects. Benzodiazepines bind at the interface of the α and γ subunits on the GABAA receptor. Binding also requires that alpha subunits contain a histidine amino acid residue, (i.e., α1, α2, α3, and α5 containing GABAA receptors). For this reason, benzodiazepines show no affinity for GABAA receptors containing α4 and α6 subunits with an arginine instead of a histidine residue. Once bound to the benzodiazepine receptor, the benzodiazepine ligand locks the benzodiazepine receptor into a conformation in which it has a greater affinity for the GABA neurotransmitter. This increases the frequency of the opening of the associated chloride ion channel and hyperpolarizes the membrane of the associated neuron. The inhibitory effect of the available GABA is potentiated, leading to sedative and anxiolytic effects. For instance, those ligands with high activity at the α1 are associated with stronger hypnotic effects, whereas those with higher affinity for GABAA receptors containing α2 and/or α3 subunits have good anti-anxiety activity.

GABAA receptors participate in the regulation of synaptic pruning by prompting microglial spine engulfment. Benzodiazepines have been shown to upregulate microglial spine engulfment and prompt overzealous eradication of synaptic connections. This mechanism may help explain the increased risk of dementia associated with long-term benzodiazepine treatment.

The benzodiazepine class of drugs also interact with peripheral benzodiazepine receptors. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptors are present in peripheral nervous system tissues, glial cells, and to a lesser extent the central nervous system. These peripheral receptors are not structurally related or coupled to GABAA receptors. They modulate the immune system and are involved in the body response to injury. Benzodiazepines also function as weak adenosine reuptake inhibitors. It has been suggested that some of their anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, and muscle relaxant effects may be in part mediated by this action. Benzodiazepines have binding sites in the periphery, however their effects on muscle tone is not mediated through these peripheral receptors. The peripheral binding sites for benzodiazepines are present in immune cells and gastrointestinal tract.

Pharmacokinetics

| Benzodiazepine | Half-life (range, hours) |

Speed of onset |

|---|---|---|

| Alprazolam | 6–15 | Intermediate |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 10–30 | Intermediate |

| Clonazepam | 19–60 | Slow |

| Diazepam | 20–80 | Fast |

| Flunitrazepam | 18–26 | Fast |

| Lorazepam | 10–20 | Intermediate |

| Midazolam | 1.5–2.5 | Fast |

| Oxazepam | 5–10 | Slow |

| Prazepam | 50–200 | Slow |

| Triazolam | 1.5 | Fast |

A benzodiazepine can be placed into one of three groups by its elimination half-life, or time it takes for the body to eliminate half of the dose. Some benzodiazepines have long-acting active metabolites, such as diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, which are metabolised into desmethyldiazepam. Desmethyldiazepam has a half-life of 36–200 hours, and flurazepam, with the main active metabolite of desalkylflurazepam, with a half-life of 40–250 hours. These long-acting metabolites are partial agonists.

- Short-acting compounds have a median half-life of 1–12 hours. They have few residual effects if taken before bedtime, rebound insomnia may occur upon discontinuation, and they might cause daytime withdrawal symptoms such as next day rebound anxiety with prolonged usage. Examples are brotizolam, midazolam, and triazolam.

- Intermediate-acting compounds have a median half-life of 12–40 hours. They may have some residual effects in the first half of the day if used as a hypnotic. Rebound insomnia, however, is more common upon discontinuation of intermediate-acting benzodiazepines than longer-acting benzodiazepines. Examples are alprazolam, estazolam, flunitrazepam, clonazepam, lormetazepam, lorazepam, nitrazepam, and temazepam.

- Long-acting compounds have a half-life of 40–250 hours. They have a risk of accumulation in the elderly and in individuals with severely impaired liver function, but they have a reduced severity of rebound effects and withdrawal. Examples are diazepam, clorazepate, chlordiazepoxide, and flurazepam.

Chemistry

Benzodiazepines share a similar chemical structure, and their effects in humans are mainly produced by the allosteric modification of a specific kind of neurotransmitter receptor, the GABAA receptor, which increases the overall conductance of these inhibitory channels; this results in the various therapeutic effects as well as adverse effects of benzodiazepines. Other less important modes of action are also known.

The term benzodiazepine is the chemical name for the heterocyclic ring system (see figure to the right), which is a fusion between the benzene and diazepine ring systems. Under Hantzsch–Widman nomenclature, a diazepine is a heterocycle with two nitrogen atoms, five carbon atom and the maximum possible number of cumulative double bonds. The "benzo" prefix indicates the benzene ring fused onto the diazepine ring.

Benzodiazepine drugs are substituted 1,4-benzodiazepines, although the chemical term can refer to many other compounds that do not have useful pharmacological properties. Different benzodiazepine drugs have different side groups attached to this central structure. The different side groups affect the binding of the molecule to the GABAA receptor and so modulate the pharmacological properties. Many of the pharmacologically active "classical" benzodiazepine drugs contain the 5-phenyl-1H-benzo diazepin-2(3H)-one substructure (see figure to the right). Benzodiazepines have been found to mimic protein reverse turns structurally, which enable them with their biological activity in many cases.

Nonbenzodiazepines also bind to the benzodiazepine binding site on the GABAA receptor and possess similar pharmacological properties. While the nonbenzodiazepines are by definition structurally unrelated to the benzodiazepines, both classes of drugs possess a common pharmacophore (see figure to the lower-right), which explains their binding to a common receptor site.

Types

- 2-keto compounds:

- clorazepate, diazepam, flurazepam, halazepam, prazepam, and others

- 3-hydroxy compounds:

- 7-nitro compounds:

- Triazolo compounds:

- Imidazo compounds:

- 1,5-benzodiazepines:

History

The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium), was synthesized in 1955 by Leo Sternbach while working at Hoffmann–La Roche on the development of tranquilizers. The pharmacological properties of the compounds prepared initially were disappointing, and Sternbach abandoned the project. Two years later, in April 1957, co-worker Earl Reeder noticed a "nicely crystalline" compound left over from the discontinued project while spring-cleaning in the lab. This compound, later named chlordiazepoxide, had not been tested in 1955 because of Sternbach's focus on other issues. Expecting pharmacology results to be negative, and hoping to publish the chemistry-related findings, researchers submitted it for a standard battery of animal tests. The compound showed very strong sedative, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant effects. These impressive clinical findings led to its speedy introduction throughout the world in 1960 under the brand name Librium. Following chlordiazepoxide, diazepam marketed by Hoffmann–La Roche under the brand name Valium in 1963, and for a while the two were the most commercially successful drugs. The introduction of benzodiazepines led to a decrease in the prescription of barbiturates, and by the 1970s they had largely replaced the older drugs for sedative and hypnotic uses.

The new group of drugs was initially greeted with optimism by the medical profession, but gradually concerns arose; in particular, the risk of dependence became evident in the 1980s. Benzodiazepines have a unique history in that they were responsible for the largest-ever class-action lawsuit against drug manufacturers in the United Kingdom, involving 14,000 patients and 1,800 law firms that alleged the manufacturers knew of the dependence potential but intentionally withheld this information from doctors. At the same time, 117 general practitioners and 50 health authorities were sued by patients to recover damages for the harmful effects of dependence and withdrawal. This led some doctors to require a signed consent form from their patients and to recommend that all patients be adequately warned of the risks of dependence and withdrawal before starting treatment with benzodiazepines. The court case against the drug manufacturers never reached a verdict; legal aid had been withdrawn and there were allegations that the consultant psychiatrists, the expert witnesses, had a conflict of interest. The court case fell through, at a cost of £30 million, and led to more cautious funding through legal aid for future cases. This made future class action lawsuits less likely to succeed, due to the high cost from financing a smaller number of cases, and increasing charges for losing the case for each person involved.

Although antidepressants with anxiolytic properties have been introduced, and there is increasing awareness of the adverse effects of benzodiazepines, prescriptions for short-term anxiety relief have not significantly dropped. For treatment of insomnia, benzodiazepines are now less popular than nonbenzodiazepines, which include zolpidem, zaleplon and eszopiclone. Nonbenzodiazepines are molecularly distinct, but nonetheless, they work on the same benzodiazepine receptors and produce similar sedative effects.

Benzodiazepines have been detected in plant specimens and brain samples of animals not exposed to synthetic sources, including a human brain from the 1940s. However, it is unclear whether these compounds are biosynthesized by microbes or by plants and animals themselves. A microbial biosynthetic pathway has been proposed.

Society and culture

Legal status

In the United States, benzodiazepines are Schedule IV drugs under the Federal Controlled Substances Act, even when not on the market (for example, nitrazepam and bromazepam). Flunitrazepam is subject to more stringent regulations in certain states and temazepam prescriptions require specially coded pads in certain states.

In Canada, possession of benzodiazepines is legal for personal use. All benzodiazepines are categorized as Schedule IV substances under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

In the United Kingdom, benzodiazepines are Class C controlled drugs, carrying the maximum penalty of 7 years imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both for possession and a maximum penalty of 14 years imprisonment an unlimited fine or both for supplying benzodiazepines to others.

In the Netherlands, since October 1993, benzodiazepines, including formulations containing less than 20 mg of temazepam, are all placed on List 2 of the Opium Law. A prescription is needed for possession of all benzodiazepines. Temazepam formulations containing 20 mg or greater of the drug are placed on List 1, thus requiring doctors to write prescriptions in the List 1 format.

In East Asia and Southeast Asia, temazepam and nimetazepam are often heavily controlled and restricted. In certain countries, triazolam, flunitrazepam, flutoprazepam and midazolam are also restricted or controlled to certain degrees. In Hong Kong, all benzodiazepines are regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. Previously only brotizolam, flunitrazepam and triazolam were classed as dangerous drugs.

Internationally, benzodiazepines are categorized as Schedule IV controlled drugs, apart from flunitrazepam, which is a Schedule III drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Recreational use

Main articles: Benzodiazepine drug misuse and Drug-related crime

Benzodiazepines are considered major addictive substances. Non-medical benzodiazepine use is mostly limited to individuals who use other substances, i.e., people who engage in polysubstance use. On the international scene, benzodiazepines are categorized as Schedule IV controlled drugs by the INCB, apart from flunitrazepam, which is a Schedule III drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Some variation in drug scheduling exists in individual countries; for example, in the United Kingdom, midazolam and temazepam are Schedule III controlled drugs.

British law requires that temazepam (but not midazolam) be stored in safe custody. Safe custody requirements ensures that pharmacists and doctors holding stock of temazepam must store it in securely fixed double-locked steel safety cabinets and maintain a written register, which must be bound and contain separate entries for temazepam and must be written in ink with no use of correction fluid (although a written register is not required for temazepam in the United Kingdom). Disposal of expired stock must be witnessed by a designated inspector (either a local drug-enforcement police officer or official from health authority). Benzodiazepine use ranges from occasional binges on large doses, to chronic and compulsive drug use of high doses.

Benzodiazepines are commonly used recreationally by poly-drug users. Mortality is higher among poly-drug users that also use benzodiazepines. Heavy alcohol use also increases mortality among poly-drug users. Polydrug use involving benzodiazepines and alcohol can result in an increased risk of blackouts, risk-taking behaviours, seizures, and overdose. Dependence and tolerance, often coupled with dosage escalation, to benzodiazepines can develop rapidly among people who misuse drugs; withdrawal syndrome may appear after as little as three weeks of continuous use. Long-term use has the potential to cause both physical and psychological dependence and severe withdrawal symptoms such as depression, anxiety (often to the point of panic attacks), and agoraphobia. Benzodiazepines and, in particular, temazepam are sometimes used intravenously, which, if done incorrectly or in an unsterile manner, can lead to medical complications including abscesses, cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, arterial puncture, deep vein thrombosis, and gangrene. Sharing syringes and needles for this purpose also brings up the possibility of transmission of hepatitis, HIV, and other diseases. Benzodiazepines are also misused intranasally, which may have additional health consequences. Once benzodiazepine dependence has been established, a clinician usually converts the patient to an equivalent dose of diazepam before beginning a gradual reduction program.

A 1999–2005 Australian police survey of detainees reported preliminary findings that self-reported users of benzodiazepines were less likely than non-user detainees to work full-time and more likely to receive government benefits, use methamphetamine or heroin, and be arrested or imprisoned. Benzodiazepines are sometimes used for criminal purposes; they serve to incapacitate a victim in cases of drug assisted rape or robbery.

Overall, anecdotal evidence suggests that temazepam may be the most psychologically habit-forming (addictive) benzodiazepine. Non-medical temazepam use reached epidemic proportions in some parts of the world, in particular, in Europe and Australia, and is a major addictive substance in many Southeast Asian countries. This led authorities of various countries to place temazepam under a more restrictive legal status. Some countries, such as Sweden, banned the drug outright. Temazepam also has certain pharmacokinetic properties of absorption, distribution, elimination, and clearance that make it more apt to non-medical use compared to many other benzodiazepines.

Veterinary use

Benzodiazepines are used in veterinary practice in the treatment of various disorders and conditions. As in humans, they are used in the first-line management of seizures, status epilepticus, and tetanus, and as maintenance therapy in epilepsy (in particular, in cats). They are widely used in small and large animals (including horses, swine, cattle and exotic and wild animals) for their anxiolytic and sedative effects, as pre-medication before surgery, for induction of anesthesia and as adjuncts to anesthesia.

References

- ^ Shorter E (2005). "Benzodiazepines". A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-19-517668-1.

- Balon R, Starcevic V, Silberman E, Cosci F, Dubovsky S, Fava GA, et al. (9 March 2020). "The rise and fall and rise of benzodiazepines: a return of the stigmatized and repressed". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 42 (3): 243–244. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2019-0773. PMC 7236156. PMID 32159714.

- Treating Alcohol and Drug Problems in Psychotherapy Practice Doing What Works. New York: Guilford Publications. 2011. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4625-0438-1.

- ^ Page C, Michael C, Sutter M, Walker M, Hoffman BB (2002). Integrated Pharmacology (2nd ed.). C.V. Mosby. ISBN 978-0-7234-3221-0.

- ^ Olkkola KT, Ahonen J (2008). "Midazolam and Other Benzodiazepines". In Schüttler J, Schwilden H (eds.). Modern Anesthetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 182. pp. 335–360. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_16. ISBN 978-3-540-72813-9. PMID 18175099.

- ^ Dikeos DG, Theleritis CG, Soldatos CR (2008). "Benzodiazepines: effects on sleep". In Pandi-Perumal SR, Verster JC, Monti JM, Lader M, Langer SZ (eds.). Sleep Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Informa Healthcare. pp. 220–222. ISBN 978-0-415-43818-6.

- Ashton H (May 2005). "The diagnosis and management of benzodiazepine dependence". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (3): 249–255. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165594.60434.84. PMID 16639148. S2CID 1709063.

- ^ Saïas T, Gallarda T (September 2008). "". L'Encéphale (in French). 34 (4): 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2007.05.005. PMID 18922233.

- "Benzodiazepines". Better Health Channel. 19 May 2023.

- ^ Dodds TJ (March 2017). "Prescribed Benzodiazepines and Suicide Risk: A Review of the Literature". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 19 (2). doi:10.4088/PCC.16r02037. PMID 28257172.

- ^ Lader M (2008). "Effectiveness of benzodiazepines: do they work or not?". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics (PDF). 8 (8): 1189–1191. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.8.1189. PMID 18671662. S2CID 45155299.

- ^ Lader M, Tylee A, Donoghue J (2009). "Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care". CNS Drugs. 23 (1): 19–34. doi:10.2165/0023210-200923010-00002. PMID 19062773. S2CID 113206.

- ^ Penninkilampi R, Eslick GD (June 2018). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Risk of Dementia Associated with Benzodiazepine Use, After Controlling for Protopathic Bias". CNS Drugs. 32 (6): 485–497. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0535-3. PMID 29926372. S2CID 49351844.

- Kim HB, Myung SK, Park YC, Park B (February 2017). "Use of benzodiazepine and risk of cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies". International Journal of Cancer. 140 (3): 513–525. doi:10.1002/ijc.30443. PMID 27667780. S2CID 25777653.

- ^ Ashton H (May 2005). "The diagnosis and management of benzodiazepine dependence" (PDF). Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (3): 249–255. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165594.60434.84. PMID 16639148. S2CID 1709063.

- ^ McIntosh A, Semple D, Smyth R, Burns J, Darjee R (2005). "Depressants". Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-19-852783-1.

- By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (November 2015). "American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 63 (11). The American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel: 2227–2246. doi:10.1111/jgs.13702. PMID 26446832. S2CID 38797655.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics (April 2008). "ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 92: Use of Psychiatric Medications During Pregnancy and Lactation". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 111 (4): 1001–1020. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816fd910. PMID 18378767.

- ^ Fraser AD (October 1998). "Use and abuse of the benzodiazepines". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 20 (5): 481–489. doi:10.1097/00007691-199810000-00007. PMC 2536139. PMID 9780123.

- "FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 31 August 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Charlson F, Degenhardt L, McLaren J, Hall W, Lynskey M (2009). "A systematic review of research examining benzodiazepine-related mortality". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 18 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1002/pds.1694. PMID 19125401. S2CID 20125264.

- ^ White JM, Irvine RJ (July 1999). "Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose". Addiction. 94 (7): 961–972. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479612.x. PMID 10707430.

- ^ Lader MH (1999). "Limitations on the use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and insomnia: are they justified?". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 9 (Suppl 6): S399–405. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00051-6. PMID 10622686. S2CID 43443180.

- ^ British National Formulary (BNF 57). Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. 2009. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

- ^ Perugi G, Frare F, Toni C (2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of agoraphobia with panic disorder". CNS Drugs. 21 (9): 741–764. doi:10.2165/00023210-200721090-00004. PMID 17696574. S2CID 43437233.

- Tesar GE (May 1990). "High-potency benzodiazepines for short-term management of panic disorder: the U.S. experience". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 51 (Suppl): 4–10, discussion 50–53. PMID 1970816.

- Faught E (2004). "Treatment of refractory primary generalized epilepsy". Reviews in Neurological Diseases. 1 (Suppl 1): S34–43. PMID 16400293.

- Allgulander C, Bandelow B, Hollander E, Montgomery SA, Nutt DJ, Okasha A, et al. (August 2003). "WCA recommendations for the long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". CNS Spectrums. 8 (Suppl 1): 53–61. doi:10.1017/S1092852900006945. PMID 14767398. S2CID 32761147.

- "Benzodiazepines in chronic pain". February 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Alexander GC, Rutkow L, Mojtabai R (October 2017). "Emergency department visits involving benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 35 (10): 1414–1419. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.04.023. PMC 5623103. PMID 28476551.

- Stevens JC, Pollack MH (2005). "Benzodiazepines in clinical practice: consideration of their long-term use and alternative agents". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (Suppl 2): 21–27. PMID 15762816.

The frequent use of benzodiazepines for the treatment of anxiety is likely a reflection of their effectiveness, rapid onset of anxiolytic effect, and tolerability.

- ^ McIntosh A, Cohen A, Turnbull N, et al. (2004). "Clinical guidelines and evidence review for panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder" (PDF). National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, Kasper S, Möller HJ (October 2002). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 3 (4): 171–199. doi:10.3109/15622970209150621. PMID 12516310. S2CID 922780.

- ^ "APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Panic Disorder, Second Edition" (PDF). Work Group on Panic Disorder. January 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- Barbui C, Cipriani A (2009). "Proposal for the inclusion in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines of a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor for Generalised Anxiety Disorder" (PDF). WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- Cloos JM, Ferreira V (January 2009). "Current use of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 22 (1): 90–95. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32831a473d. PMID 19122540. S2CID 20715355.

- Martin JL, Sainz-Pardo M, Furukawa TA, Martín-Sánchez E, Seoane T, Galán C (September 2007). "Benzodiazepines in generalized anxiety disorder: heterogeneity of outcomes based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 21 (7): 774–782. doi:10.1177/0269881107077355. PMID 17881433. S2CID 1879448.

- "Clinical Guideline 22 (amended). Anxiety: management of anxiety (panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, and generalised anxiety disorder) in adults in primary, secondary and community care" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2007. pp. 23–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- Canadian Psychiatric Association (July 2006). "Clinical practice guidelines. Management of anxiety disorders". The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry (PDF). 51 (8 Suppl 2): 9S – 91S. PMID 16933543. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ Bandelow B, Reitt M, Röver C, Michaelis S, Görlich Y, Wedekind D (July 2015). "Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 30 (4): 183–192. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000078. PMID 25932596. S2CID 24088074.

- "Current problems" (PDF). www.mhra.gov.uk. 1988. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Technology Appraisal Guidance 77. Guidance on the use of zaleplon, zolpidem and zopiclone for the short-term management of insomnia" (PDF). National Institute for Clinical Excellence. April 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ^ Ramakrishnan K, Scheid DC (August 2007). "Treatment options for insomnia". American Family Physician. 76 (4): 517–526. PMID 17853625.

- Carlstedt RA (13 December 2009). Handbook of Integrative Clinical Psychology, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Medicine: Perspectives, Practices, and Research. Springer Publishing Company. pp. 128–130. ISBN 978-0-8261-1094-7.

- ^ Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, Bialy L, Tubman M, Ospina M, et al. (June 2005). "Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 125" (PDF). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Alexander GC, Rutkow L, Mojtabai R (June 2016). "Trends in prescribing of sedative-hypnotic medications in the USA: 1993–2010". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 25 (6): 637–645. doi:10.1002/pds.3951. PMC 4889508. PMID 26711081.

- "Approval letter for Ambien" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ American Geriatrics Society. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013., which cites

- ^ Allain H, Bentué-Ferrer D, Polard E, Akwa Y, Patat A (2005). "Postural instability and consequent falls and hip fractures associated with use of hypnotics in the elderly: a comparative review". Drugs & Aging. 22 (9): 749–765. doi:10.2165/00002512-200522090-00004. PMID 16156679. S2CID 9296501.

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (April 2012). "American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (4). American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel: 616–631. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. PMC 3571677. PMID 22376048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults" (PDF). Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2005. pp. 17–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ Stokes T, Shaw EJ, Juarez-Garcia A, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Baker R (October 2004). Clinical Guidelines and Evidence Review for the Epilepsies: diagnosis and management in adults and children in primary and secondary care (PDF). London: Royal College of General Practitioners. pp. 61, 64–65. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ Shorvon SD (March 2009). "Drug treatment of epilepsy in the century of the ILAE: the second 50 years, 1959-2009". Epilepsia. 50 (Suppl 3): 93–130. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02042.x. PMID 19298435. S2CID 20445985.

- Stokes T, Shaw EJ, Juarez-Garcia A, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Baker R (October 2004). "Clinical Guidelines and Evidence Review for the Epilepsies: diagnosis and management in adults and children in primary and secondary care (Appendix B)" (PDF). London: Royal College of General Practitioners. p. 432. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Ashworth M, Gerada C (August 1997). "ABC of mental health. Addiction and dependence – II: Alcohol". BMJ. 315 (7104): 358–360. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7104.358. PMC 2127236. PMID 9270461.

- Kraemer KL, Conigliaro J, Saitz R (June 1999). "Managing alcohol withdrawal in the elderly". Drugs & Aging. 14 (6): 409–425. doi:10.2165/00002512-199914060-00002. PMID 10408740. S2CID 2724630.

- Prater CD, Miller KE, Zylstra RG (September 1999). "Outpatient detoxification of the addicted or alcoholic patient". American Family Physician. 60 (4): 1175–1183. PMID 10507746.

- Ebell MH (April 2006). "Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal". American Family Physician. 73 (7): 1191. PMID 16623205.

- Peppers MP (1996). "Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal in the elderly and in patients with liver disease". Pharmacotherapy. 16 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1996.tb02915.x. PMID 8700792. S2CID 1389910. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Devlin JW, Roberts RJ (July 2009). "Pharmacology of commonly used analgesics and sedatives in the ICU: benzodiazepines, propofol, and opioids". Critical Care Clinics. 25 (3): 431–49, vii. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2009.03.003. PMID 19576523.

- Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM (May 2015). "Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis". Critical Care Medicine. 43 (5): 1121–1129. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. PMID 25654178. S2CID 11478971.

- Simon ST, Higginson IJ, Booth S, Harding R, Weingärtner V, Bausewein C (October 2016). "Benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (10): CD007354. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007354.pub3. PMC 6464146. PMID 27764523.

- Broscheit J, Kranke P (February 2008). "". Anästhesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin, Schmerztherapie. 43 (2): 134–143. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1060547. PMID 18293248. S2CID 259982203.

- Berthold C (May 2007). "Enteral sedation: safety, efficacy, and controversy". Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 28 (5): 264–271, quiz 272, 282. PMID 17607891.

- Mañon-Espaillat R, Mandel S (January 1999). "Diagnostic algorithms for neuromuscular diseases". Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 16 (1): 67–79. doi:10.1016/S0891-8422(23)00935-7. PMID 9929772. S2CID 12493035.

- Kamen L, Henney HR, Runyan JD (February 2008). "A practical overview of tizanidine use for spasticity secondary to multiple sclerosis, stroke, and spinal cord injury". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 24 (2): 425–439. doi:10.1185/030079908X261113. PMID 18167175. S2CID 73086671.