Pharmaceutical compound

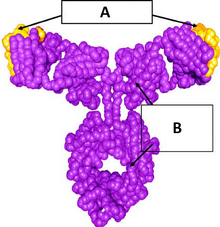

Omalizumab structure: (A) murine complementarity-determining region and (B) IgG1κ human framework Omalizumab structure: (A) murine complementarity-determining region and (B) IgG1κ human framework | |

| Monoclonal antibody | |

|---|---|

| Type | Whole antibody |

| Source | Humanized (from mouse) |

| Target | IgE Fc region |

| Clinical data | |

| Pronunciation | /ˌoʊməˈlɪzumæb/ OH-mə-LI-zoo-mab |

| Trade names | Xolair |

| Biosimilars | Omlyclo |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603031 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 26 days |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6450H9916N1714O2023S38 |

| Molar mass | 145058.53 g·mol |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Omalizumab, sold under the brand name Xolair among others, is an injectable medication to treat severe persistent allergic forms of asthma, nasal polyps, urticaria (hives), and immunoglobulin E-mediated food allergy.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody which specifically binds to free human immunoglobulin E (IgE) in the blood and interstitial fluid and to the membrane-bound form of IgE (mIgE) on the surface of mIgE-expressing B lymphocytes. Its primary adverse effect is anaphylaxis.

In 1987, Tanox filed its first patent application on the anti-IgE drug candidates. It took until 2003 in the United States until omalizumab was approved, and in Europe until 2005 for moderate to severe persistent asthma and severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. In February 2024, the FDA approved it also to treat severe food allergy.

Medical uses

In the United States, omalizumab is indicated to treat moderate to severe persistent asthma, severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and chronic idiopathic urticaria, and as of February 2024, food allergy.

In the European Union, omalizumab is indicated to treat allergic asthma, chronic (long-term) spontaneous urticaria (itchy rash), and severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.

In Australia, omalizumab is indicated to treat allergic asthma and chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Allergic asthma

Omalizumab is used to treat people with severe, persistent allergic asthma that is not controlled with oral or injectable corticosteroids. Those patients have already failed step I to step IV treatments and are in step V of treatment. Such a treatment scheme is consistent with the widely adopted guidelines for the management and prevention of asthma, issued by Global Initiative of Asthma (GINA), which was a medical guidelines organization launched in 1993 in collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, US, and the World Health Organization. A 2014 Cochrane review found that omalizumab was effective in reducing exacerbations and hospitalisations related to asthma when used as an adjunct to steroids.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria

Omalizumab is indicated for chronic spontaneous urticaria in adults and adolescents (>12 years old) poorly responsive to H1-antihistamine therapy. When administered subcutaneously once every four weeks, omalizumab has been shown to significantly decrease itch severity and hive count.

Food allergy

In February 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added an indication for immunoglobulin E-mediated food allergy for the reduction of allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, which may occur with accidental exposure to one or more foods. Omalizumab can be used as a monotherapy or in combination with oral immunotherapy.

Chemistry and formulations

Omalizumab is a glycosylated IgG1 monoclonal antibody produced by cells of an adapted Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line. The antibody molecules are secreted by the host cells in a cell culture process employing large-scale bioreactors. At the end of culturing, the IgG contained in the medium is purified by an affinity-column using Protein A as the adsorbent, followed by chromatography steps, and finally concentrated by UF/DF (paired ultra filtration/depth filtration).

Mechanism of action

The rationale for designing the anti-IgE therapeutic antibodies and the pharmacological mechanisms of anti-IgE therapy have been summarized in articles by the inventor of the anti-IgE therapy. Unlike an ordinary anti-IgE antibody, it does not bind to IgE that is already bound by the high affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) on the surface of mast cells, basophils, and antigen-presenting dendritic cells.

Perhaps the most dramatic effect, which was not foreseen at the time when the anti-IgE therapy was designed and which was discovered during clinical trials, is that as the free IgE in patients is depleted by omalizumab, the FcεRI receptors on basophils, mast cells, and dendritic cells are gradually down-regulated with somewhat different kinetics, rendering those cells much less sensitive to stimulation by allergens. Thus, therapeutic anti-IgE antibodies such as omalizumab represent a new class of potent mast cell stabilizers. This is now thought to be the fundamental mechanism for omalizumab's effects on allergic and non-allergic diseases involving mast cell degranulation. Many investigators have identified or elucidated a host of pharmacological effects, which help bring down the inflammatory status in omalizumab-treated patients.

IgE in allergic diseases

In conjunction with achieving the practical goal to investigate the applicability of the anti-IgE therapy as a potential treatment for allergic diseases, the many corporate-sponsored clinical trials of TNX-901 and omalizumab on asthma, allergic rhinitis, peanut allergy, chronic idiopathic urticaria, atopic dermatitis, and other allergic diseases, have helped define the role of IgE in the pathogenesis of these prevalent allergic diseases. For example, the clinical trial results of omalizumab on asthma have unambiguously settled the long debate on whether IgE plays a central role in the pathogenesis of asthma. Numerous investigator-initiated case studies or small-scale pilot studies of omalizumab have been performed on various allergic diseases and several non-allergic diseases, especially inflammatory skin diseases. These diseases include atopic dermatitis, various subtypes of physical urticaria (solar, cold-induced, local heat-induced, or delayed pressure-induced), and a spectrum of relatively less prevalent allergic or non-allergic diseases or conditions, such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, cutaneous or systemic mastocytosis, bee venom sensitivity (anaphylaxis), idiopathic anaphylaxis, eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorder, bullous pemphigoid, interstitial cystitis, nasal polyps, and idiopathic angioedema.

Roles in non-allergic diseases

Several groups have reported clinical trial results that omalizumab may be effective in patients with non-allergic asthma. This seems to be contrary to the general understanding of the pharmacological mechanisms of the anti-IgE therapy discussed above. Furthermore, among the diseases in which omalizumab has been studied for efficacy and safety, some are not allergic diseases, because hypersensitivity reactions toward external antigens is not involved. For example, a portion of the cases of chronic idiopathic urticaria and all cases of bullous pemphigoid are clearly autoimmune diseases. For the remaining cases of chronic idiopathic urticaria and those of the different subtypes of physical urticaria, the internal abnormalities leading to the disease manifestation have not been identified. Notwithstanding these developments, it is apparent that many of those diseases involve inflammatory reactions in the skin and the activation of mast cells. An increasing series of papers have shown that IgE potentiates the activities of mast cells, while omalizumab can function as a mast cell-stabilizing agent, rendering these inflammatory cells less active.

Adverse effects

Omalizumab's primary adverse effect is anaphylaxis (a life-threatening systemic allergic reaction), with a rate of occurrence of 1 to 2 patients per 1,000. A Cochrane review found injection site reactions to be the main reported adverse reaction.

Limited studies are available to confirm whether omalizumab increases the risk of developing cardiovascular (CV) or cerebrovascular disease (CBV). Cohort and randomised controlled studies have shown that the risk of developing CV/CBV disease is around 20–32% higher in patients taking omalizumab compared to those not taking omalizumab. Additional multi-national, longitudinal studies with increased subject numbers are required to provide further clarification into the relationship and clinical significance between omalizumab and CV/CBV disease. Due to the severity of CV/CBVs side effects, clinicians and health care providers should continue to remain vigilant and monitor side effects when treating patients with omalizumab.

IgE may play an important role in the immune system's recognition of cancer cells. Therefore, indiscriminate blocking of IgE-receptor interaction with omalizumab may have unforeseen risks. The data pooled in 2003 from the earlier phase I to phase III clinical trials showed a numeric imbalance in malignancies arising in omalizumab recipients (0.5%) compared with control subjects (0.2%). A 2012 study found that a causal link with cancer was unlikely.

History

In 1983, the product concept of anti-IgE antibodies against autologous IgE epitopes was discovered by perinatal monoclonal IgE immunization in rodents prior to the emergence of endogenous self IgE by Swey-Shen Chen at the Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) and in Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), and later confirmed by Dr. Alfred Nisonoff at Brandeis University using monoclonal IgE in incomplete Freund's adjuvant in perinates.

Tanox, a biopharmaceutical company based in Houston, Texas, started the anti-IgE program, created antibody drug candidates, and in 1987 filed its first patent application on the anti-IgE therapeutic approach. In 1988, the company converted one candidate antibody to a chimeric antibody (which was later named CGP51901 and further developed into a humanized antibody, TNX-901 or talizumab). The anti-IgE therapeutic concept was not well received in the early period of the program. Representatives of Ciba-Geigy (which merged with Sandoz to form Novartis in 1996) thought the anti-IgE program scientifically interesting and executives from Tanox and Ciba-Geigy signed a collaborative agreement in 1990 to develop the anti-IgE program.

In 1991, after several rounds of pre-IND ("investigational new drug") meetings with officials/scientists of the FDA, the FDA finally allowed CGP51901 to be tested in human subjects. This approval of IND for an anti-IgE antibody for the first time was regarded a brave demonstration of professionalism for both the FDA officials and the Tanox/Ciba-Geigy team. The scientists participating in the pre-IND discussion comprehended that an ordinary anti-IgE antibody (i.e., one without the set of the binding specificity of CGP51901) would invariably activate mast cells and basophils and cause anaphylactic shock and probably deaths among injected persons. Notwithstanding this concern, they came to the same view that based on the presented scientific data, CGP51901 should have an absolutely required clean distinction from an ordinary anti-IgE antibody in this regard. In 1991–1993, researchers from Ciba-Geigy and Tanox and a leading clinical research group (headed by Stephen Holgate) in the asthma/allergy field ran a successful Phase I human clinical trial of CGP51901 in Southampton, England, and showed that the tested antibody is safe. In 1994–1995, the Tanox/Ciba-Geigy team conducted a Phase II trial of CGP51901 in patients with severe allergic rhinitis in Texas and showed that CGP51901 is safe and efficacious in relieving allergic symptoms.

While the Tanox/Ciba-Geigy anti-IgE program was gaining momentum, Genentech announced in 1993 that it also had an anti-IgE program for developing antibody therapeutics for asthma and other allergic diseases. Scientists in Genentech had made a mouse anti-IgE monoclonal antibody with the binding specificity similar to that of CGP51901 and subsequently humanized the antibody (the antibody was later named "omalizumab"). This caused great concerns in Tanox, because it had disclosed its anti-IgE technology and sent its anti-IgE antibody candidate, which was to become CGP51901 and TNX-901, to Genentech in 1989 for the latter to evaluate for the purpose of considering establishing a corporate partnership. Having failed to receive reconciliation from Genentech, Tanox filed a lawsuit against Genentech for trade secret violation. Coincidentally, Tanox started to receive major patents for its anti-IgE invention from the European Union and from the U.S. in 1995. After a 3-year legal entanglement, Genentech and Tanox settled their lawsuits out-of-court and Tanox, Novartis, and Genentech formed a tripartite partnership to jointly develop the anti-IgE program in 1996. Omalizumab became the drug of choice for further development, because it had a better developed manufacturing process than TNX-901. A large number of corporate-sponsored clinical trials and physician-initiated case series studies on omalizumab have been planned and performed since 1996 and a large number of research reports, especially those of clinical trial results, have been published since around 2000, as described and referenced in other sections of this article. In 2007, Genentech bought Tanox at $20/share for approximately $900 Million.

Society and culture

Legal status

Omalizumab was approved for medical use in the US in June 2003.

In October 2005, EMA issued the marketing authorization for omalizumab for the therapeutic indication of obstructive airway disease to Novartis.

The FDA approval of omalizumab for food allergy in February 2024 was based on the OUtMATCH trial, a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study that evaluated its efficacy and safety in those allergic to peanut and two other foods, including milk, egg, wheat, cashew, hazelnut, or walnut. The FDA granted the application breakthrough therapy designation.

In March 2024, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Omlyclo, intended for the treatment of severe persistent allergic asthma, severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). The applicant for this medicinal product is Celltrion Healthcare Hungary Kft. Omlyclo is a biosimilar medicinal product. It is highly similar to the reference product Xolair (omalizumab), which was authorized in the EU in October 2005. Omlyclo was approved for medical use in the European Union in May 2024.

Economics

In August 2010, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom ruled that omalizumab should not be prescribed on the National Health Service (NHS) to children under 12, as the high costs of the compound, over £250 per vial, did not represent a sufficiently high increase in quality of life. However, in March 2013, NICE issued "final draft guidance" about the allowance of omalizumab, recommending the medication as an option for treating severe, persistent allergic asthma in adults, adolescents and children following additional analyses and submission of a "patient access scheme" by Novartis, the manufacturer.

In August 2013, a senior Dutch researcher at Leiden University Medical Center responsible for the TIGER trial to treat rheumatoid arthritis was fired for research fraud. The TIGER trial was halted as a result.

As of 2020 in the United States, omalizumab cost about US$540 to $4,600 per month.

References

- ^ "Omlyclo EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 21 March 2024. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Omlyclo Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. 24 May 2024. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- "Australian Public Assessment Report for Omalizumab" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration. April 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "AusPAR Xolair Omalizumab Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd PM-2014-03868-1-5" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration. 22 June 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- "Regulatory Decision Summary - Xolair - Health Canada". Government of Canada. 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc (26 September 2017). "Product Monograph: Pr Xolair Omalizumab" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- "Regulatory Decision Summary for Xolair". Drug and Health Products Portal. 8 February 2024. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- "Xolair 75 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Xolair- omalizumab injection, solution Xolair PFS- omalizumab injection, solution". DailyMed. 11 May 2020. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Xolair EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "FDA Approves First Medication to Help Reduce Allergic Reactions to Multiple Foods After Accidental Exposure". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 16 February 2024. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Presta LG, Lahr SJ, Shields RL, Porter JP, Gorman CM, Fendly BM, et al. (1993). "Humanization of an Antibody Directed Against IgE". The Journal of Immunology. 151 (5): 2623–2632. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.151.5.2623. PMID 8360482.

- Schulman ES (October 2001). "Development of a monoclonal anti-immunoglobulin E antibody (omalizumab) for the treatment of allergic respiratory disorders". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 164 (8 Pt 2): S6–11. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.supplement_1.2103025. PMID 11704611.

- ^ Davydov L (January 2005). "Omalizumab (Xolair) for treatment of asthma". Am Fam Physician. 71 (2): 341–2. PMID 15686303.

- "Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention. Global Initiatives for Asthma". 2013. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, Walters EH, Nair P (January 2014). "Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (1): CD003559. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003559.pub4. PMC 10981784. PMID 24414989.

- ^ Urgert MC, van den Elzen MT, Knulst AC, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ (August 2015). "Omalizumab in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and GRADE assessment". The British Journal of Dermatology. 173 (2): 404–15. doi:10.1111/bjd.13845. PMID 25891046. S2CID 22874727.

- ^ Bernstein JA, Kavati A, Tharp MD, Ortiz B, MacDonald K, Denhaerynck K, et al. (April 2018). "Effectiveness of omalizumab in adolescent and adult patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review of 'real-world' evidence". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 18 (4): 425–448. doi:10.1080/14712598.2018.1438406. PMID 29431518.

- Zhao ZT, Ji CM, Yu WJ, Meng L, Hawro T, Wei JF, et al. (June 2016). "Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 137 (6): 1742–1750.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1342. PMID 27040372.

- Zuberbier T, Wood RA, Bindslev-Jensen C, Fiocchi A, Chinthrajah RS, Worm M, et al. (April 2023). "Omalizumab in IgE-Mediated Food Allergy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 11 (4): 1134–46. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.11.036. PMID 36529441.

- ^ Chang TW, Wu PC, Hsu CL, Hung AF (2007). Anti-IgE Antibodies for the Treatment of IgE-Mediated Allergic Diseases. Advances in Immunology. Vol. 93. pp. 63–119. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(06)93002-8. ISBN 978-0-12-373707-6. PMID 17383539.

- Chang TW (February 2000). "The pharmacological basis of anti-IgE therapy". Nat. Biotechnol. 18 (2): 157–62. doi:10.1038/72601. PMID 10657120. S2CID 22688959.

- ^ Chang TW, Shiung YY (June 2006). "Anti-IgE as a mast cell-stabilizing therapeutic agent". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 117 (6): 1203–12. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.005. PMID 16750976.

- MacGlashan DW, Bochner BS, Adelman DC, Jardieu PM, Togias A, McKenzie-White J, et al. (February 1997). "Down-regulation of Fc(epsilon)RI expression on human basophils during in vivo treatment of atopic patients with anti-IgE antibody". Journal of Immunology. 158 (3): 1438–45. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.158.3.1438. PMID 9013989. S2CID 193264.

- Prussin C, Griffith DT, Boesel KM, Lin H, Foster B, Casale TB (December 2003). "Omalizumab treatment downregulates dendritic cell FcepsilonRI expression". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 112 (6): 1147–54. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.003. PMID 14657874. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Scheinfeld N (2005). "Omalizumab: a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgE-blocking antibody". Dermatol. Online J. 11 (1): 2. doi:10.5070/D30MC9C9TW. PMID 15748543.

- Holgate ST, Djukanović R, Casale T, Bousquet J (April 2005). "Anti-immunoglobulin E treatment with omalizumab in allergic diseases: an update on anti-inflammatory activity and clinical efficacy". Clin. Exp. Allergy. 35 (4): 408–16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02191.x. PMID 15836747. S2CID 6504882.

- ^ Holgate S, Casale T, Wenzel S, Bousquet J, Deniz Y, Reisner C (March 2005). "The anti-inflammatory effects of omalizumab confirm the central role of IgE in allergic inflammation". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 115 (3): 459–65. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.053. PMID 15753888.

- Holgate S, Smith N, Massanari M, Jimenez P (December 2009). "Effects of omalizumab on markers of inflammation in patients with allergic asthma". Allergy. 64 (12): 1728–36. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02201.x. PMID 19839977. S2CID 205404340.

- van der Ent CK, Hoekstra H, Rijkers GT (March 2007). "Successful treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with recombinant anti-IgE antibody". Thorax. 62 (3): 276–7. doi:10.1136/thx.2004.035519. PMC 2117163. PMID 17329558.

- Kontou-Fili K, Filis CI, Voulgari C, Panayiotidis PG (June 2010). "Omalizumab monotherapy for bee sting and unprovoked "anaphylaxis" in a patient with systemic mastocytosis and undetectable specific IgE". Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 104 (6): 537–9. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2010.04.011. PMID 20568389.

- ^ Fairley JA, Baum CL, Brandt DS, Messingham KA (March 2009). "Pathogenicity of IgE in autoimmunity: successful treatment of bullous pemphigoid with omalizumab". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 123 (3): 704–5. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.035. PMC 4784096. PMID 19152970.

- Lee J, Doggweiler-Wiygul R, Kim S, Hill BD, Yoo TJ (May 2006). "Is interstitial cystitis an allergic disorder?: A case of interstitial cystitis treated successfully with anti-IgE". Int. J. Urol. 13 (5): 631–4. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01373.x. PMID 16771742. S2CID 34830352.

- Sands MF, Blume JW, Schwartz SA (October 2007). "Successful treatment of 3 patients with recurrent idiopathic angioedema with omalizumab". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 120 (4): 979–81. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.041. PMID 17931567.

- de Llano LP, Vennera MC, Alvarez FJ, Medina JF, Borderias L, Pellicer C, et al. (April 2013). "Effects of omalizumab in non-atopic asthma: results from a Spanish multicenter registry". J Asthma. 50 (3): 296–301. doi:10.3109/02770903.2012.757780. PMID 23350994. S2CID 26426416.

- Lommatzsch M, Korn S, Buhl R, Virchow JC (May 2013). "Against all odds: anti-IgE for intrinsic asthma?". Thorax. 69 (1): 94–6. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203738. PMC 3888607. PMID 23709757.

- Maurer M, Rosén K, Hsieh HJ, Saini S, Grattan C, Gimenéz-Arnau A, et al. (March 2013). "Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria". The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (10): 924–35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215372. PMID 23432142. S2CID 205095225.

- Kaplan A, Ledford D, Ashby M, Canvin J, Zazzali JL, Conner E, et al. (July 2013). "Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 132 (1): 101–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.013. PMID 23810097.

- Kashiwakura J, Otani IM, Kawakami T (2011). "Monomeric IgE and Mast Cell Development, Survival and Function". Mast Cell Biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 716. pp. 29–46. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9533-9_3. ISBN 978-1-4419-9532-2. PMID 21713650.

- Fanta CH (March 2009). "Asthma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (10): 1002–14. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804579. PMID 19264689.

- ^ Iribarren C, Rahmaoui A, Long AA, Szefler SJ, Bradley MS, Carrigan G, et al. (May 2017). "Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events among patients receiving omalizumab: Results from EXCELS, a prospective cohort study in moderate to severe asthma". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 139 (5): 1489–1495.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.038. PMID 27639934. S2CID 1230144.

- ^ Iribarren C, Rothman KJ, Bradley MS, Carrigan G, Eisner MD, Chen H (May 2017). "Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events among patients receiving omalizumab: Pooled analysis of patient-level data from 25 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 139 (5): 1678–1680. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.953. PMID 28108337.

- Karagiannis SN, Wang Q, East N, Burke F, Riffard S, Bracher MG, et al. (April 2003). "Activity of human monocytes in IgE antibody-dependent surveillance and killing of ovarian tumor cells". Eur. J. Immunol. 33 (4): 1030–40. doi:10.1002/eji.200323185. PMID 12672069. S2CID 29495137.

- Busse W, Buhl R, Fernandez Vidaurre C, Blogg M, Zhu J, Eisner MD, et al. (April 2012). "Omalizumab and the risk of malignancy: results from a pooled analysis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 129 (4): 983–9.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.033. PMID 22365654.

- Chen SS, Katz DH (February 1983). "IgE class-restricted tolerance induced by neonatal administration of soluble or cell-bound IgE". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 157 (2): 772–88. doi:10.1084/jem.157.2.772. PMC 2186933. PMID 6600492.

- Chen SS, Liu FT, Katz DH (October 1984). "IgE class-restricted tolerance induced by neonatal administration of soluble or cell-bound IgE. Cellular mechanisms". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 160 (4): 953–70. doi:10.1084/jem.160.4.953. PMC 2187471. PMID 6237166.

- Chen SS (February 1992). "Genesis of host IgE competence: perinatal IgE tolerance induced by IgE processed and presented by IgE Fc receptor (CD23)-bearing B cells". European Journal of Immunology. 22 (2): 343–8. doi:10.1002/eji.1830220209. PMID 1531635. S2CID 25625576.

- Haba S, Nisonoff A (July 1987). "Induction of high titers of anti-IgE by immunization of inbred mice with syngeneic IgE". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (14): 5009–13. Bibcode:1987PNAS...84.5009H. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.14.5009. PMC 305236. PMID 2440038.

- ^ Twombly R. Couple Lead Quest for New Allergy Drug. The Scientist 7 January 1991. http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/11548/title/Couple-Lead-Quest-For-New-Allergy-Drug/ Archived 27 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Development and Licensing Agreement, between Tanox and Ciba-Geigy 1990. "Development and Licensing Agreement - Tanox Biosystems Inc. And Ciba-Geigy Ltd. - Sample Contracts and Business Forms". Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- Chang TW, Davis FM, Sun NC, Sun CR, MacGlashan DW Jr, Hamilton RG (February 1990). "Monoclonal antibodies specific for human IgE-producing B cells: a potential therapeutic for IgE-mediated allergic diseases". Bio/Technology. 8 (2): 122–6. doi:10.1038/nbt0290-122. PMID 1369991. S2CID 10510009.

- Davis FM, Gossett LA, Pinkston KL, Liou RS, Sun LK, Kim YW, et al. (1993). "Can anti-IgE be used to treat allergy?". Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 15 (1): 51–73. doi:10.1007/BF00204626. PMID 8362344. S2CID 32440234.

- Corne J, Djukanovic R, Thomas L, Warner J, Botta L, Grandordy B, et al. (March 1997). "The effect of intravenous administration of a chimeric anti-IgE antibody on serum IgE levels in atopic subjects: efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics". J Clin Invest. 99 (5): 879–87. doi:10.1172/JCI119252. PMC 507895. PMID 9062345.

- Racine-Poon A, Botta L, Chang TW, Davis FM, Gygax D, Liou RS, et al. (December 1997). "Efficacy, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of CGP 51901, an anti-immunoglobulin E chimeric monoclonal antibody, in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 62 (6): 675–90. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90087-4. PMID 9433396. S2CID 28652703.

- ^ Thorpe H (1 April 1995). "Drug war. (small drug firm Tanox takes on Genentech over patent rights)". Texas Monthly. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- The family of anti-IgE patents. "Methods for producing high affinity anti-human IgE-monoclonal antibodies which binds to IgE on IgE-bearing B cells but not basophils". Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2012.; "Chimeric anti-human IgE-monoclonal antibody which binds to secreted IgE and membrane-bound IgE expressed by IgE-expressing B cells but notto IgE bound to FC receptors on basophils". Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2012.; "Monoclonal antibodies that bind to soluble IGE but do not bind IGE on IGE expressing B lymphocytes or basophils". Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2012.; "Treating hypersensitivities with anti-IGE monoclonal antibodies which bind to IGE-expressing B cells but not basophils". Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2012.; "Humanized monoclonal antibodies binding to IgE-bearing B cells but not basophils". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2012..

- ^ Tripartite Cooperation Agreement, by and between NOVARTIS PHARMA AG, GENENTECH, INC, AND TANOX, INC. "Tripartite Cooperation Agreement". Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "Genentech: Press Releases - Genentech Announces Agreement to Acquire Tanox for $20 Per Share". www.gene.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013.

- Tansey B (3 August 2007). "Genentech completes acquisition / $919 million for Tanox is its first purchase ever". Sfgate. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016.

- "FDA Approves Xolair (omalizumab) for Moderate-to-Severe Asthma". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- "CY 2024 CDER Breakthrough Therapy Calendar Year Approvals" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 September 2024.

- "Meeting highlights from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) 18-21 March 2024". European Medicines Agency (Press release). 22 March 2024. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- "Asthma drug ruling 'nonsensical'". BBC News. 12 August 2010. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010.

- NICE says yes to treatment for asthma in final draft guidance. NICE 7 March 2013. "News". Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Sheldon T (August 2013). "Senior Dutch researcher sacked for manipulating data in rheumatoid arthritis drug trial". BMJ. 347: f5267. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5267. PMID 23974641. S2CID 42283648.

- Davydov L (January 2005). "Omalizumab (Xolair) for treatment of asthma". American Family Physician. 71 (2): 341–2. PMID 15686303. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

| Immunosuppressive drugs / Immunosuppressants (L04) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular (initiation) |

| ||||||||||||||

| Intracellular (reception) |

| ||||||||||||||

| Extracellular |

| ||||||||||||||

| Unsorted |

| ||||||||||||||

| Monoclonal antibodies for the immune system | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune system |

| ||||||||||

| Interleukin |

| ||||||||||

| Inflammatory lesions |

| ||||||||||

| |||||||||||