This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Jayden54 (talk | contribs) at 18:51, 25 November 2006 (Revert to revision 90025981 dated 2006-11-25 14:38:05 by Jpgordon using popups). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:51, 25 November 2006 by Jayden54 (talk | contribs) (Revert to revision 90025981 dated 2006-11-25 14:38:05 by Jpgordon using popups)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Cocaine (disambiguation). Pharmaceutical compound| File:Cocaine-2D-skeletal.png | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Medium |

| Routes of administration | Topical, Oral, Insufflation, IV, PO |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: 30% Nasal: 30-60% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic CYP3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour |

| Excretion | Renal (benzoylecgonine and ecgonine methyl ester) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.030 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 303.353 g/mol g·mol |

| Melting point | 195 °C (383 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 1800 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| Data page | |

| Cocaine (data page) | |

Cocaine is a crystalline tropane alkaloid that is obtained from the leaves of the coca plant. It is a stimulant of the central nervous system and an appetite suppressant, creating what has been described as a euphoric sense of happiness and increased energy. Though most often used recreationally for this effect, cocaine is also a topical anesthetic used in eye, throat, and nose surgery. Cocaine can be psychologically addictive, and its possession, cultivation, and distribution is illegal for non-medicinal and non-government sanctioned purposes in virtually all parts of the world. The name comes from the name of the coca plant plus the alkaloid suffix -ine.

The stimulating qualities of the coca leaf were known to the ancient peoples of Peru and other Pre-Columbian South American societies. In modern Western countries, cocaine has been a feature of the counterculture for well-over a century; there is a long-list of prominent intellectuals, artists, and musicians who have used the drug — names ranging from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sigmund Freud to United States President Ulysses S. Grant. For several decades after its initial release, cocaine could be found in trace amounts in the Coca-Cola beverage. Today, although illegal in virtually all countries, cocaine remains popular in a wide variety of social and personal settings.

History

The coca leaf

South American indigenous peoples have chewed the coca leaf (Erythroxylum coca), a plant that contains vital nutrients as well as numerous alkaloids, including cocaine. The leaf was, and is, chewed almost universally by some indigenous communities—ancient Peruvian mummies have been found with the remains of coca leaves deposited in their mouths, and pottery from the time period depicts humans whose cheeks are bulged with the presence of something on which they are chewing.However, it should be noted that there is no evidence that its habitual use has ever led to any of the negative consequences generally associated with habitual cocaine use today. There is evidence that these cultures used a mixture of coca leaves and saliva as an anesthetic for the performance of trepanation.

When the Spaniards colonized South America, they at first ignored aboriginal claims that the leaf gave them strength and energy, and declared the chewing of coca leaves a satanic practice. But after discovering that these claims were true, they legalized and taxed the leaf, taking 10 percent off the value of each crop. These taxes were for a time the main source of support for the Roman Catholic Church in the region. In 1569, Nicholas Monardes described the practice of the natives of chewing a mixture of tobacco and coca leaves to induce "great contentment":

make themselves drunk and out of judgment make them go as they were out of their wittes

In 1609, Padre Blas Valera wrote:

Coca protects the body from many ailments, and our doctors use it in powdered form to reduce the swelling of wounds, to strengthen broken bones, to expel cold from the body or prevent it from entering, and to cure rotten wounds or sores that are full of maggots. And if it does so much for outward ailments, will not its singular virtue have even greater effect in the entrails of those who eat it?

Isolation

Although the stimulant and hunger-suppressant properties of coca had been known for many centuries, the isolation of the cocaine alkaloid was not achieved until 1855. Many scientists had attempted to isolate cocaine, but none had been successful for two reasons: the knowledge of chemistry required was insufficient at the time, worsened because coca does not grow in Europe and ruins easily during travel.

The cocaine alkaloid was first isolated by the German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855. Gaedcke named the alkaloid “erythroxyline,” and published a description in the journal Archives de Pharmacie.

In 1856, Friedrich Wöhler asked Dr. Carl Scherzer, a scientist aboard the Novara (an Austrian frigate sent by Emperor Franz Joseph to circle the globe), to bring him a large amount of coca leaves from South America. In 1859, the ship finished its travels and Wöhler received a trunk full of coca. Wöhler passed on the leaves to Albert Niemann, a Ph.D. student at the University of Göttingen in Germany, who then developed an improved purification process.

Niemann described every step he took to isolate cocaine in his dissertation titled Über eine neue organische Base in den Cocablättern (On a New Organic Base in the Coca Leaves), which was published in 1860—it earned him his Ph. D. and is now in the British Library. He wrote of the alkaloid's “colourless transparent prisms” and said that, “Its solutions have an alkaline reaction, a bitter taste, promote the flow of saliva and leave a peculiar numbness, followed by a sense of cold when applied to the tongue.” Niemann named the alkaloid “Cocain”—as with other alkaloids its name carried the “-in” ending (derived from the Latin suffix -ina).

Medicalization

With the discovery of this new alkaloid, Western medicine was quick to jump upon and exploit the possible uses of this plant.

In 1879, Vassili von Anrep, of the University of Würzburg, devised an experiment to demonstrate the analgesic properties of the newly-discovered alkaloid. He prepared two separate jars, one containing a cocaine-salt solution, with the other containing merely salt water. He then submerged a frog's legs into the two jars, one leg in the treatment and one in the control solution, and proceeded to stimulate the legs in several different ways. The leg that had been immersed in the cocaine solution reacted very differently than the leg that had been immersed in salt water.

Carl Koller (a close associate of Sigmund Freud, who would write about cocaine later) experimented with cocaine for ophthalmic usage. In an infamous experiment in 1884, he experimented upon himself by applying a cocaine solution to his own eye and then pricking it with pins. His findings were presented to the Heidelberg Ophthalmological Society. Also in 1884, Jellinek demonstrated the effects of cocaine as a respiratory system anesthetic. In 1885, William Halsted demonstrated nerve-block anesthesia, and James Corning demonstrated peridural anesthesia. In 1898, Heinrich Quincke used cocaine for spinal anesthesia.

Popularization

In 1859, an Italian doctor, Paolo Mantegazza returned from Peru, where he had witnessed first-hand the use of coca by the natives. He proceeded to experiment on himself and upon his return to Milan he wrote a paper in which he described the effects. In this paper he declared coca and cocaine (at the time they were assumed to be the same) as being useful medicinally, in the treatment of “a furred tongue in the morning, flatulence, whitening of the teeth.”

A chemist named Angelo Mariani who read Mantegazza’s paper became immediately intrigued with coca and its economic potential. In 1863, Mariani started marketing a wine called Vin Mariani, which had been treated with coca leaves. The ethanol in wine acted as a solvent and extracted the cocaine from the coca leaves, altering the drink’s effect. It contained 6 mg cocaine per ounce of wine, but Vin Mariani, which was to be exported, contained 7.2 mg per ounce to compete with the higher cocaine content of similar drinks in the United States. A “pinch of coca leaves” was included in John Styth Pemberton's original 1886 recipe for Coca-Cola, though the company began using decocainized leaves in 1906 when the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed. The only known measure of the amount of cocaine in Coca-Cola was determined in 1902 as being as little as 1/400 of a grain (0.2 mg) per ounce of syrup (6 ppm). The actual amount of cocaine that Coca-Cola contained during the first twenty years of its production is practically impossible to determine.

In 1879 cocaine began to be used to treat morphine addiction. Cocaine was introduced into clinical use as a local anaesthetic in Germany in 1884, about the same time as Sigmund Freud published his work Über Coca (On Coca), in which he wrote that cocaine causes:

...exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which in no way differs from the normal euphoria of the healthy person...You perceive an increase of self-control and possess more vitality and capacity for work....In other words, you are simply normal, and it is soon hard to believe you are under the influence of any drug....Long intensive physical work is performed without any fatigue...This result is enjoyed without any of the unpleasant after-effects that follow exhilaration brought about by alcohol....Absolutely no craving for the further use of cocaine appears after the first, or even after repeated taking of the drug...

In 1885 the U.S. manufacturer Parke-Davis sold cocaine in various forms, including cigarettes, powder, and even a cocaine mixture that could be injected directly into the user’s veins with the included needle. The company promised that its cocaine products would “supply the place of food, make the coward brave, the silent eloquent and... render the sufferer insensitive to pain.”

By the late Victorian era cocaine use had appeared as a vice in literature; for example, Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional Sherlock Holmes injects a "seven-percent solution" of the drug in The Sign of Four.

In 1909, Ernest Shackleton took “Forced March” brand cocaine tablets to Antarctica, as did Captain Scott a year later on his ill-fated journey to the South Pole. Even as late as 1938, the Larousse Gastronomique was published carrying a recipe for “cocaine pudding”.

Prohibition

By the turn of the twentieth century, the addictive properties of cocaine had become clear to many, and the problem of cocaine abuse began to capture public attention in the United States. The dangers of cocaine abuse became part of a moral panic that was tied to the dominant racial and social anxieties of the day. In 1903, the American Journal of Pharmacy stressed that most cocaine abusers were “bohemians, gamblers, high- and low-class prostitutes, night porters, bell boys, burglars, racketeers, pimps, and casual laborers.” In 1914, Dr. Christopher Koch of Pennsylvania’s State Pharmacy Board made the racial innuendo explicit, testifying that, “Most of the attacks upon the white women of the South are the direct result of a cocaine-crazed Negro brain.” Mass media perpetuated an epidemic of cocaine use among African Americans in the Southern United States to play upon racial prejudices of the era, though there is little evidence that such an epidemic actually took place. In the same year, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act outlawed the use of cocaine in the United States. This law incorrectly referred to cocaine as a narcotic, and the misclassification passed into popular culture. As stated above, cocaine is a stimulant, not a narcotic.

Modern usage

| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In many countries, cocaine is a popular recreational drug. In the United States, the development of "crack" cocaine introduced the substance to a generally poorer inner-city market. Use of the powder form has stayed relatively constant, experiencing a new height of use during the late 1990's, however, use has dropped somewhat from the early 2000's giving way to MDMA which has increased in popularity. Cocaine has become much more popular in the last few years in the UK.

Cocaine use is prevalent across all socioeconomic strata, including age, demographics, economic, social, political, religious, and livelihood. Cocaine in its various forms comes in second only to cannabis as the most popular illegal recreational drug in the United States, and is number one in street value sold each year.

The estimated U.S. cocaine market exceeded $35 billion in street value for the year 2003. There is a tremendous demand for cocaine in the U.S. market, particularly among those who are making incomes affording luxury spending, such as single adults and various professionals. Cocaine’s status as a club drug shows its immense popularity among the “party crowd.”

In 1995 the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) announced in a press release the publication of the results of the largest global study on cocaine use ever undertaken. However, a decision in the World Health Assembly banned the publication of the study. In the sixth meeting of the B committee the US representative threatened that "If WHO activities relating to drugs failed to reinforce proven drug control approaches, funds for the relevant programmes should be curtailed". This led to the decision to discontinue publication. A part of the study has been recuperated. Available are profiles of cocaine use in 20 countries. Some of the findings were that "Generally cocaine users consume a range of other drugs as well. There appears to be very little 'pure' cocaine use. Overall, fewer people in participating countries have used cocaine than have used alcohol, tobacco or cannabis. Also, in most countries, cocaine is not the drug associated with the greatest problems.", "There is a complex relationship between cocaine use and crime, particularly theft and violence.", "In most participating countries, a minority of people start using cocaine or related products, use casually for a short or long period, and suffer little or no negative consequences, even after years of use. This suggests it is possible to reduce, if not entirely eliminate, harmful cocaine use."

A problem with illegal cocaine use, especially in the higher volumes used to combat fatigue (rather than increase euphoria) by long-term users is trauma caused by the compounds used in adulteration. Cutting or "stepping on" the drug is commonplace, using compounds which simulate ingestion effects, such as novocaine producing temporary anasthaesia, ephedrine producing an increased heart rate, or more dangerously, strong toxins to produce vasodilatory effects. For example a nosebleed is foolishly regarded by heavy users as a sign of purity. The normal adulterants for profit are inactive sugars, usually mannitol, creatine or glucose, so introducing active adulterants gives the illusion of purity. Cocaine trading carries large penalties in most jurisdictions, so user deception about purity and consequent high profits for dealers are the norm.

Pharmacology

Appearance

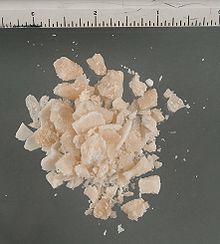

Cocaine in its purest form is a white, pearly product. Cocaine appearing in powder form is a salt, typically cocaine hydrochloride (CAS 53-21-4). Black market cocaine is frequently adulterated or “cut” with various powdery fillers to increase its surface area; the substances most commonly used in this process are baking soda; sugars, such as lactose, dextrose, inositol, and mannitol; and local anesthetics, such as lidocaine or benzocaine, which mimic or add to cocaine's numbing effect on mucous membranes. Cocaine may also be "cut" with other stimulants such as methamphetamine. Adulterated cocaine is often a white, off-white or pinkish powder.

The color of “crack” cocaine depends upon several factors including the origin of the cocaine used, the method of preparation – with ammonia or sodium bicarbonate – and the presence of impurities, but will generally range from white to a yellowish creme to a light brown. Its texture will also depend on the adulterants, origin and processing of the powdered cocaine, and the method of converting the base; but will range from a crumbly texture, sometimes extremely oily, to a hard, almost crystalline nature.

Forms of cocaine

Cocaine sulfate

Cocaine sulfate is produced by macerating coca leaves along with water that has been acidulated with sulfuric acid, or a aromatic-based solvent, like kerosene or benzene. This is often accomplished by putting the ingredients into a vat and stamping on it, in a manner similar to the traditional method for crushing grapes. After the cocaine is extracted, the water is evaporated to yield a pasty mass of impure cocaine sulfate.

The sulfate itself is an intermediate step to producing cocaine hydrochloride. In South America, it is commonly smoked along with tobacco, and is known as pasta, basuco, basa, pitillo, paco or simply paste. It is also gaining popularity as a cheap drug (.30-.70 U.S. cents per "hit" or dose) in Argentina.

Freebase

Main article: FreebaseAs the name implies, “freebase” is the base form of cocaine, as opposed to the salt form of cocaine hydrochloride. Whereas cocaine hydrochloride is extremely soluble in water, cocaine base is insoluble in water and is therefore not suitable for drinking, snorting or injecting. Cocaine hydrochloride is not well-suited for smoking because the temperature at which it vaporizes is very high, and close to the temperature at which it burns; however, cocaine base vaporizes at a low temperature, which makes it suitable for inhalation.

Smoking freebase is preferred by many users because the cocaine is absorbed immediately into blood via the lungs, where it reaches the brain in about five seconds. The rush is much more intense than sniffing the same amount of cocaine nasally, but the effects do not last as long. The peak of the freebase rush is over almost as soon as the user exhales the vapor, but the high typically lasts 5–10 minutes afterward. What makes freebasing particularly dangerous is that users typically don't wait that long for their next hit and will continue to smoke freebase until none is left. These effects are similar to those that can be achieved by injecting or “slamming” cocaine hydrochloride, but without the risks associated with intravenous drug use (though there are other serious risks associated with smoking freebase).

Freebase cocaine is produced by first dissolving cocaine hydrochloride in water. Once dissolved in water, cocaine hydrochloride (Coc HCl) dissociates into protonated cocaine ion (Coc-H) and chloride ion (Cl). Any solids that remain in the solution are not cocaine (they are part of the cut) and are removed by filtering. A base, typically ammonia (NH3), is added to the solution. The following net chemical reaction takes place:

Coc-HAs freebase cocaine (Coc) is insoluble in water, it precipitates and the solution becomes cloudy. To recover the freebase, a nonpolar solvent like diethyl ether is added to the solution: Because freebase is highly soluble in ether, a vigorous shaking of the mixture results in the freebase being dissolved in the ether. As ether is insoluble in water, it can be siphoned off. The ether is then evaporated, leaving behind the cocaine base.

Handling diethyl ether is dangerous because ether is extremely flammable, its vapors are heavier than air and can “creep” from an open bottle, and in the presence of oxygen it can form peroxides, which can spontaneously combust. Demonstrative of the dangers of the practice, the famous comedian Richard Pryor used to perform a well known skit in which he poked fun at himself over a 1980 incident in which he caused an explosion and set himself on fire while attempting to smoke “freebase”, presumably while still wet with ether.

Crack cocaine

Due to the dangers of using ether to produce pure freebase cocaine, cocaine producers began to omit the step of removing the freebase cocaine precipitate from the ammonia mixture. Typically, filtration processes are also omitted. The end result of this process is that the cut, in addition to the ammonium salt (NH4Cl), remains in the freebase cocaine after the mixture is evaporated. The “rock” that is thus formed also contains a small amount of water. Sodium bicarbonate is also preferred in preparing the freebase, for when commonly "cooked" the ratio is 50/50 to 40/60 percent cocaine/bicarbonate. This acts as a filler which extends the overall profitability of illicit sales. Crack cocaine may be reprocessed in small quantities with water (users refer to the resultant product as "cookback"). This removes the residual bicarbonate, and any adulterants or cuts that have been used in the previous handling of the cocaine and leaves a relatively pure, anhydrous cocaine base.

When the rock is heated, this water boils, making a crackling sound (hence the onomatopoeic “crack”). Baking soda is now most often used as a base rather than ammonia for reasons of lowered stench and toxicity; however, any weak base can be used to make crack cocaine. Strong bases, such as sodium hydroxide, tend to hydrolyze some of the cocaine into non-psychoactive ecgonine.

The net reaction when using baking soda (also called sodium bicarbonate, with a chemical formula of NaHCO3) is:

Coc-HCl + NaHCO3 → Coc + H2O + CO2 + NaClCrack is unique because it offers a strong cocaine experience in small, low-priced packages. In the United States, crack cocaine is often sold in small, inexpensive dosage units frequently known as a "blast" (equivalent to one hit or a dollars worth), “nickels”, “nickel rocks”, or "bumps" (referring to the price of $5.00), and also “dimes”, “dime rocks”, or "boulders" and sometimes as “twenties”, “solids", "slabs" and “forties.” The quantity provided by such a purchase varies depending upon many factors, such as local availability, which is affected by geographic location. A twenty may yield a quarter gram or half gram on average, yielding 30 minutes to an hour of effect if hits are taken every few minutes. After the $20 or $40 mark, crack and powder cocaine are sold in grams or fractions of ounces. At the intermediate level, crack cocaine is sold either by weight in ounces, referred to by terms such as "eight-ball" (one-eighth of an ounce) or "quarter" and "half" respectively. In the alternate, $20 pieces of crack cocaine are aggregated in units of "fifty pack" and "hundred pack", referring to the number of pieces. At this level, the wholesale price is approximately half the street sale price.

Crack cocaine was extremely popular in the mid- and late 1980s in a period known as the Crack Epidemic, especially in inner cities, though its popularity declined through the 1990s in the United States. There were major anti-drug campaigns launched in the U.S. to try and cull its popularity, the most popular being a series of ads featuring the slogan "The Thrill Can Kill". However, there has been an increase in popularity within Canada in the recent years, where it has been estimated that the drug has become a multi-billion dollar 'industry'.

Although consisting of the same active drug as powder cocaine, crack cocaine in the United States is seen as a drug primarily by and for the inner-city poor; the stereotypical "crack head" is poor, urban, and usually homeless. While insufflated powder cocaine has an associated glamour attributed to its popularity among mostly middle and upper class whites (as well as musicians and entertainers), crack is perceived as a skid row drug of squalor and desperation. The U.S. federal trafficking penalties deal far more harshly towards crack when compared to powdered cocaine. Possession of five grams of crack (or over 500 grams of powder) carries a minimum sentence of five years imprisonment in the US.

Modes of administration

Chewed/eaten

Coca leaves typically are mixed with an alkaline substance (such as lime) and chewed into a wad that is retained in the mouth between gum and cheek and sucked of its juices. The juices are absorbed slowly by the mucous membrane of the inner cheek and by the gastro-intestinal tract when swallowed. Alternatively, coca leaves can be infused in liquid and consumed like tea. Ingesting coca leaves generally is an inefficient means of administering cocaine. It should be remembered that the coca leaf is not actual cocaine, and is not a drug of any kind. Because cocaine is hydrolyzed (rendered inactive) in the acidic stomach, it is not readily absorbed. Only when mixed with a highly alkaline substance (such as lime) can it be absorbed into the bloodstream through the stomach. Absorption of orally administered cocaine is limited by two additional factors. First, the drug is partly metabolized in the liver. Second, capillaries in the mouth and esophagus constrict after contact with the drug, reducing the surface area over which the drug can be absorbed.

Orally administered cocaine takes approximately 30 minutes to enter the bloodstream. Typically, only 30 percent of an oral dose is absorbed, although absorption has been shown to reach 60 percent in controlled settings. Given the slow rate of absorption, maximum physiological and psychotropic effects are attained approximately 60 minutes after cocaine is administered by ingestion. While the onset of these effects is slow, the effects are sustained for approximately 60 minutes after their peak is attained.

Contrary to popular belief, both ingestion and insufflation result in approximately the same proportion of the drug being absorbed: 30 to 60 percent. G. Barnett, R. Hawks and R. Resnick, "Cocaine Pharmacokinetics in Humans," 3 Journal of Ethnopharmacology 353 (1981); Jones, supra note 19; Wilkinson et al., Van Dyke et al., Compared to ingestion, the faster absorption of insufflated cocaine results in quicker attainment of maximum drug effects. Snorting cocaine produces maximum physiological effects within 40 minutes and maximum psychotropic effects within 20 minutes, However a more realistic activation period is closer to 5 to 10 minutes, which is similar to ingestion of cocaine. Physiological and psychotropic effects from nasally insufflated cocaine are sustained for approximately 40 - 60 minutes after the peak effects are attained. Van Dyke, et al.

Mate de coca or coca-leaf tea is also a traditional method of consumption and is often recommended to treat altitude sickness. This method of consumption has been practiced for thousands of years by South American natives. One specific purpose of ancient coca leaf consumption was to increase energy and reduce fatigue in messengers who made multi-day quests to other settlements.

In 1986 an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association revealed that health food stores were selling coca-leaf tea as “Health Inca Tea.” While the packaging claimed it had been “decocainized,” no such process had taken place—they were selling a controlled substance off the shelves. The article stated that drinking two cups of the tea per day gave a mild stimulation, increased heart rate, and mood elevation, and the tea was essentially harmless. Despite this, the DEA seized several shipments in Hawaii, Chicago, Illinois, Georgia, and several locations on the East Coast of the United States, and the product was removed from the shelves.

Insufflation

Insufflation (known colloquially as “snorting," “sniffing," or "blowing") is the most common method of ingestion of recreational powder cocaine in the Western world. Contrary to widespread belief, cocaine is not actually inhaled using this method; rather the drug coats and is absorbed through the mucous membranes lining the sinuses. When insufflating cocaine, absorption through the nasal membranes is approximately 30-60 percent, with higher doses leading to increased absorption efficiency. Any material not directly absorbed through the mucous membranes is collected in mucus and swallowed (this "drip" is considered pleasant by some and unpleasant by others). In a study of cocaine users, the average time taken to reach peak subjective effects was 14.6 minutes. Chronic use results in ongoing rhinitis and necrosis of the nasal membranes. Many users report a burning sensation in the nares (nostrils) after cocaine's anasthetic effects wear off. Any damage to the inside of the nose is because cocaine highly constricts blood vessels — and therefore blood & oxygen/nutrient flow-- to that area. If this restriction of adequate blood supply is bad enough and, especially prolonged enough, the tissue there can die.

Prior to insufflation, cocaine powder must be divided into very fine particles. Cocaine of high purity breaks into fine dust very easily, except when it is moist (not well stored) and forms “chunks,” which reduces the efficiency of nasal absorption.

Rolled up banknotes, hollowed-out pens, cut straws, pointed ends of keys, and specialized spoons are often used to insufflate cocaine. Such devices are often referred to as "tooters" by users. The cocaine typically is poured onto a flat, hard surface (such as a mirror) and divided into "lines", which are then insufflated. The amount of cocaine in a line varies widely from person to person and occasion to occasion (the purity of the cocaine is also a factor), but one line is generally considered to be a single dose and is typically 35mg-100mg. However as tolerance builds rapidly in the short-term (hours), many lines are often snorted to produce greater effects.

Injected

Drug injection provides the highest blood levels of drug in the shortest amount of time. Upon injection, cocaine reaches the brain in a matter of seconds, and the exhilarating rush that follows can be so intense that it induces some users to vomit uncontrollably. In a study of cocaine users, the average time taken to reach peak subjective effects was 3.1 minutes. The euphoria passes quickly. Aside from the toxic effects of cocaine, there is also danger of circulatory emboli from the insoluble substances that may be used to cut the drug. There is also a risk of serious infection associated with the use of contaminated needles.

An injected mixture of cocaine and heroin, known as “speedball” or “moonrock”, is a particularly popular and dangerous combination, as the converse effects of the drugs actually complement each other, but may also mask the symptoms of an overdose. It has been responsible for numerous deaths, particularly in and around Los Angeles, including celebrities such as John Belushi, Chris Farley, Layne Staley and River Phoenix. Experimentally, cocaine injections can be delivered to animals such as fruit flies to study the mechanisms of cocaine addiction.

Smoked

- See also: crack cocaine above.

Smoking freebase or crack cocaine is most often accomplished using a pipe made from a small glass tube about one quarter-inch (about 6 mm) in diameter and on the average, four inches long. These are sometimes called "stems", "horns", "blasters" and "straight shooters," readily available in convenience stores or smoke shops. They will sometimes contain a small paper flower and are promoted as a romantic gift. Buyers usually ask for a "rose" or a "flower." An alternate method is to use a small length of a radio antenna or similar metal tube. To avoid burning the user’s fingers and lips on the metal pipe, a small piece of paper or cardboard (such as a piece torn from a matchbook cover) is wrapped around one end of the pipe and held in place with either a rubber band or a piece of adhesive tape. A popular (usually pejorative) term for crack pipes is "glass dick."

A small piece (approximately one inch) of heavy steel or copper scouring pad — often called a "brillo" or "chore", from the scouring pads of the same name — is placed into one end of the tube and carefully packed down to approximately three-quarter inch. Prior to insertion, the "brillo" is burnt off, to remove any oily coatings that may be present. It then serves as a reduction base and flow modulator in which the "rock" can melt and boil to vapor.

Another option is to use a deep socket, say 12mm, wrapped with electrical tape. Instead of Chore Boy, users typically employ high grade (very fine) speaker wire rolled into a ball as the filter medium. A Zippo lighter is recommended because of the stronger flame, but the taste of naptha is quite noticeable. However, the socket is practically indestructible and inconspicuous.

The "rock" is placed at the end of the pipe closest to the filter and the other end of the pipe is placed in the mouth. A flame from a cigarette lighter or handheld torch is then held under the rock. As the rock is heated, it melts and burns away to vapor, which the user inhales as smoke. The effects, felt almost immediately after smoking, are very intense and do not last long — usually five to fifteen minutes. In a study of cocaine users, the average time taken to reach peak subjective effects was 1.4 minutes. Most users will want more after this time, especially frequent users. "Crack houses" depend on these cravings by providing users a place to smoke, and a ready supply of small bags for sale.

A heavily used crackpipe tends to fracture at the end from overheating with the flame used to heat the crack as the user attempts to inhale every bit of the drug on the metal wool filter. The end is often broken further as the user "pushes" the pipe. "Pushing" is a technique used to partially recover crack that hardens on the inside wall of the pipe as the pipe cools. The user pushes the metal wool filter through the pipe from one end to the other to collect the build-up inside the pipe, which is a very pure and potent form of the base. The ends of the pipe can be broken by the object used to push the filter, frequently a small screwdriver or stiff piece of wire. The user will often remove the most jagged edges and continue using the pipe until it becomes so short that it burns the lips and fingers. To continue using the pipe, the user will sometimes wrap a small piece of paper or cardboard around one end and hold it in place with a rubber band or adhesive tape. Of course, not all people who smoke crack cocaine will let it get that short, and will get a new or different pipe. The tell-tale signs of a used crack pipe are a glass tube with burn marks at one or both ends and a clump of metal wool inside. The language used to refer to the paraphernalia and practices of smoking cocaine vary tremendously across regions of the United States, as do the packaging methods utilized in the street level sale.

When smoked, cocaine is sometimes combined with other drugs, such as cannabis; often rolled into a joint or blunt. This combination is known as "primo", "hype", "shake and bake",a "turbo" a "yolabowla" "SnowCaps", "B-151er", a "cocoapuff", a "dirty" a "woo", or "geeking." Crack smokers who are being drug tested may also make their "primo" with cigarette tobacco instead of cannabis, since a crack smoker can test clean within two to three days of use, if only urine (and not hair) is being tested.

Powder cocaine is sometimes smoked, but it is inefficient as the heat involved destroys much of the chemical. One way of smoking powder is to put a "bump" into the end of an unlit cigarette, smoking it in one go as the user lights the cigarette normally.

Oral

Cocaine can aid as an oral anesthetic. Many users rub the powder along the gum line, Or onto a cigarette filter which is then smoked, which renders the gums and teeth numb: hence the colloquial names of "numbies," or "gummy," for this type of administration. This is commonly done with the small amounts of cocaine remaining on a surface after insufflation. Another oral method is to wrap up some cocaine in rolling paper and swallow it. This is called "parachuting".

Mechanism of action

The pharmacodynamics of cocaine are complex. One significant effect of cocaine on the central nervous system is the blockage of the dopamine transporter protein (DAT), hence cocaine is called a dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Brain regions that are rich with dopaminergic neurons are the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and the substantia nigra (SN). The dopamine (DA) neurons of the VTA send axons to the nucleus accumbens (nAC) and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and release DA presynaptically on the neurons in these regions. While the precise role of DA in the subjective experience of reward is controversial among neuroscientists, the release of DA in the nAC is widely considered to be responsible for cocaine's rewarding effects. This conclusion is largely based on laboratory data involving rats that are trained to self-administer cocaine intravenously (i.v.). If DA antagonists are infused directly into the nAC, well-trained rats self-administering cocaine will undergo extinction (i.e., initially increase responding only to stop completely) thereby indicating that cocaine is no longer reinforcing (i.e., rewarding) drug-seeking behavior.

A monoamine transmitter by a neuron for signal firing is normally recycled via the transporter to terminate the signal and to spare transmitter resources. The transporter binds the transmitter and pumps it out of the synaptic cleft back into the pre-synaptic neuron. There it is taken up into storage vesicles. Cocaine binds tightly at the DAT forming a complex that blocks the transporter's function, this also blocks the reuptake of the transmitter. Once released into the extracellular space (synaptic cleft) dopamine accumulates there, because the recycling mechanism is inhibited by the cocaine. This results in an enhanced and prolonged post-synaptic effect of dopaminergic signalling at dopamine receptors on the receiving neuron. Prolonged exposure to cocaine, as occurs with habitual use, leads to homeostatic dysregulation of normal (i.e., without cocaine) dopaminergic signaling via downregulation of D1 receptors and enhanced signal transduction. The decreased dopaminergic signalling after chronic cocaine use may contribute to depressive mood disorders and sensitize this important brain reward circuit to the reinforcing effects of cocaine (e.g., enhanced dopaminergic signalling only when cocaine is self-administered). This sensitization contributes to the intractable nature of addiction and relapse.

Cocaine is also a less potent blocker of the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and serotonin transporter (SERT). Cocaine also blocks sodium channels, thereby interfering with the propagation of action potentials; thus, like lignocaine and novocaine, it acts as a local anesthetic. Cocaine also causes vasoconstriction, thus reducing bleeding during minor surgical procedures. The locomotor enhancing properties of cocaine may be attributable to its enhancement of dopaminergic transmission from the substantia nigra. Recent research points to an important role of circadian mechanisms and clock genes in behavioral actions of cocaine.

Because nicotine increases the levels of dopamine in the brain, many cocaine users find that consumption of tobacco products during cocaine use enhances the euphoria. This, however, may have undesirable consequences, such as uncontrollable chain smoking during cocaine use (even users who don't normally smoke cigarettes have been known to chain smoke when using cocaine), in addition to the detrimental health effects and the additional strain on the cardiovascular system caused by tobacco.

Metabolism and excretion

Cocaine is extensively metabolized, primarily in the liver, with only about 1% excreted unchanged in the urine. The metabolism is dominated by hydrolytic ester cleavage, so the eliminated metabolites consist mostly of benzoylecgonine, the major metabolite, and in lesser amounts ecgonine methyl ester and ecgonine.

If taken with alcohol, cocaine combines with the ethanol in the liver to form cocaethylene, which is both more euphorigenic and has higher cardiovascular toxicity than cocaine by itself.

Cocaine metabolites are detectable in urine for up to four days after cocaine is used. Benzoylecgonine can be detected in urine within four hours after cocaine inhalation and remains detectable in concentrations greater than 1000 ng/ml for as long as 48 hours. Detection in hair is possible in regular users until the sections of hair grown during use are cut or fall out.

Effects and health issues

Acute

Cocaine is a potent central nervous system stimulant. Its effects can last from 20 minutes to several hours, depending upon the dosage of cocaine taken, purity, and method of administration.

The initial signs of stimulation are hyperactivity, restlessness, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate and euphoria. The euphoria is sometimes followed by feelings of discomfort and depression and a craving to experience the drug again. Sexual interest and pleasure can be amplified. Side effects can include twitching, paranoia, and impotence, which usually increases with frequent usage.

With excessive dosage the drug can produce hallucinations, paranoid delusions, tachycardia, itching, and formication.

Overdose causes tachyarrhythmias and a marked elevation of blood pressure. These can be life-threatening, especially if the user has existing cardiac problems.

The LD50 of cocaine when administered to mice is 95.1 mg/kg. Toxicity results in seizures, followed by respiratory and circulatory depression of medullar origin. This may lead to death from respiratory failure, stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, or heart-failure. Cocaine is also highly pyrogenic, because the stimulation and increased muscular activity cause greater heat production. Heat loss is inhibited by the intense vasoconstriction. Cocaine-induced hyperthermia may cause muscle cell destruction and myoglobinuria resulting in renal failure. There is no specific antidote for cocaine overdose.

Cocaine's primary acute effect on brain chemistry is to raise the amount of dopamine and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens (the pleasure center in the brain); this effect ceases, due to metabolism of cocaine to inactive compounds and particularly due to the depletion of the transmitter resources (tachyphylaxis). This can be experienced acutely as feelings of depression, as a "crash" after the initial high. Further mechanisms occur in chronic cocaine use.

Chronic

With chronic cocaine intake, brain cells functionally adapt (respond) to strong imbalances of transmitter levels in order to compensate extremes. So receptors disappear from or reappear on the cell surface, resulting more or less in an "off" or "working mode" respectively, or they change their susceptibility for binding partners (ligands) – mechanisms called down-/upregulation. Chronic cocaine use leads to a DAT upregulation, further contributing to depressed mood states. Finally, a loss of vesicular monoamine transporters, neurofilament proteins, and other morphological changes appear to indicate a long term damage of dopamine neurons.

All these effects contribute to the rise in an abuser's tolerance thus requiring a larger dosage to achieve the same effect. The lack of normal amounts of serotonin and dopamine in the brain is the cause of the dysphoria and depression felt after the initial high. The diagnostic criteria for cocaine withdrawal is characterized by a dysphoric mood, fatigue, unpleasant dreams, insomnia or hypersomnia, E.D., increased appetite, psychomotor retardation or agitation, and anxiety.

Cocaine abuse also has multiple physical health consequences. It is associated with a lifetime risk of heart attack that is seven times that of non-users. During the hour after cocaine is used, heart attack risk rises 24-fold.

Side effects from chronic smoking of cocaine include chest pain, lung trauma, shortness of breath, sore throat, hoarse voice, dyspnea, and an aching, flu-like syndrome. A common misconception is that the smoking of cocaine chemically breaks down tooth enamel and causes tooth decay. However, cocaine does often cause involuntary tooth grinding, known as bruxism, which can deteriorate tooth enamel and lead to gingivitis.

Chronic intranasal usage can degrade the cartilage separating the nostrils (the septum nasi), leading eventually to its complete disappearance. Due to the absorption of the cocaine from cocaine hydrochloride, the remaining hydrochloride forms a dilute hydrochloric acid.

Cocaine may also greatly increase this risk of developing rare autoimmune or connective tissue diseases such as lupus, Goodpasture's disease, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and other diseases. It can also cause a wide array of kidney diseases and renal failure. While these conditions are normally found in chronic use they can also be caused by short term exposure in susceptible individuals.

There have been published studies reporting that cocaine causes changes in the frontal lobe of the brain. The full extent of possible brain deterioration from cocaine use is not known.

Cocaine as a local anesthetic

Cocaine was historically useful as a topical anesthetic in eye and nasal surgery, although it is now predominantly used for nasal and lacrimal duct surgery. The major disadvantages of this use are cocaine's intense vasoconstrictor activity and potential for cardiovascular toxicity. Cocaine has since been largely replaced in Western medicine by synthetic local anaesthetics such as benzocaine, proparacaine, and tetracaine though it remains available for use if specified. If vasoconstriction is desired for a procedure (as it reduces bleeding), the anesthetic is combined with a vasoconstrictor such as phenylephrine or epinephrine. In Australia it is currently prescribed for use as a local anesthetic for conditions such as mouth and lung ulcers. Some Australian ENT specialists occasionally use cocaine within the practice when performing procedures such as nasal cauterization. In this scenario dissolved cocaine is soaked into a ball of cotton wool, which is placed in the nostril for the 10-15 minutes immediately prior to the procedure, thus performing the dual role of both numbing the area to be cauterized and also vasoconstriction.

Cocaine trade

Because of the extensive processing it undergoes during preparation, cocaine is generally treated as a 'hard drug', with severe penalties for possession and trafficking. Demand remains high, and consequently black market cocaine is quite expensive. Unprocessed cocaine, such as coca leaves, is occasionally bought and sold, but this is exceedingly rare as it is much easier and more profitable to conceal and smuggle it in powdered form.

Production

As of 1999, Colombia was the world's leading producer of cocaine. Three-quarters of the world's annual yield of cocaine was produced there, both from cocaine base imported from Peru (primarily the Huallaga Valley) and Bolivia, and from locally grown coca. There was a 28 percent increase from the amount of potentially harvestable coca plants which were grown in Colombia in 1998. This, combined with crop reductions in Bolivia and Peru, made Colombia the nation with the largest area of coca under cultivation. Coca grown for traditional purposes by indigenous communities, a use which is still present and is permitted by Colombian laws, only makes up a small fragment of total coca production, most of which is used for the illegal drug trade. Attempts to eradicate coca fields through the use of defoliants have devastated part of the farming economy in some coca growing regions of Colombia, and strains appear to have been developed that are more resistant or immune to their use. Whether these strains are natural mutations or the product of human tampering is unclear. These strains have also shown to be more potent than those previously grown, increasing profits for the drug cartels responsible for the exporting of cocaine. The cultivation of coca has become an attractive, and in some cases even necessary, economic decision on the part of many growers due to the combination of several factors, including the persistence of worldwide demand, the lack of other employment alternatives, the lower profitability of alternative crops in official crop substitution programs, the eradication-related damages to non-drug farms, and the spread of new strains of the coca plant.

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net Cultivation (km²) | 1875 | 2218 | 2007.5 | 1663 | 1662 |

| Potential Pure Cocaine Production (tonnes) | 770 | 925 | 830 | 680 | 645 |

Trafficking and distribution

Organized criminal gangs operating on a large scale dominate the cocaine trade. Most cocaine is grown and processed in South America, particularly in Colombia and Peru, and smuggled into the United States and Europe, where it is sold at huge markups.

Cocaine shipments from South America transported through Mexico or Central America are generally moved over land or by air to staging sites in northern Mexico. The cocaine is then broken down into smaller loads for smuggling across the U.S.–Mexico border. The primary cocaine importation points in the United States are in Arizona, southern California, southern Florida, and Texas. Typically, land vehicles are driven across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Cocaine is also carried in small, concealed, kilogram quantities across the border by couriers known as “mules” (or “burros”), who cross a border either legally, e.g. through a port or airport, or illegally through undesignated points along the border. The drugs may be strapped to the waist or legs or hidden in bags, or hidden in the body. If the mule gets through without being caught, the gangs will reap most of the profits. If he or she is caught however, gangs will sever all links and the mule will usually stand trial for trafficking by him- or herself.

Cocaine traffickers from Colombia, and recently Mexico, have also established a labyrinth of smuggling routes throughout the Caribbean, the Bahama Island chain, and South Florida. They often hire traffickers from Mexico or the Dominican Republic to transport the drug. The traffickers use a variety of smuggling techniques to transfer their drug to U.S. markets. These include airdrops of 500–700 kg in the Bahama Islands or off the coast of Puerto Rico, mid-ocean boat-to-boat transfers of 500–2,000 kg, and the commercial shipment of tonnes of cocaine through the port of Miami.

Bulk cargo ships are also used to smuggle cocaine to staging sites in the western Caribbean–Gulf of Mexico area. These vessels are typically 150–250 foot (50–80 m) coastal freighters that carry an average cocaine load of approximately 2.5 tonnes. Commercial fishing vessels are also used for smuggling operations. In areas with a high volume of recreational traffic, smugglers use the same types of vessels, such as go-fast boats, as those used by the local populations.

"Black cocaine"

Traffickers have also started using a method whereby a substance such as iron thiocyanate, a mixture of cobalt and ferric chloride, or a mixture of charcoal and iron filings is added to cocaine hydrochloride to produce “black cocaine.” The cocaine in this substance is not detected by standard chemical tests such as the Becton Dickinson test kit. The substance was first identified after a seizure in March 1998 in Germany, which was then tracked back to discover 250 lb of black cocaine ready for transport at Bogotá’s airport.

Addiction

| This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. When placing this tag, consider associating this request with a WikiProject. |

Cocaine addiction is the excessive intake of cocaine, and can result in physiological damage, lethargy, depression, or a potentially fatal overdose. The immediate craving to use more cocaine is strong and very common, because euphoric effects usually subside in most users within an hour of the last dosage, leading to serial cocaine readministrations, and prolonged, multi-dose binge use in those who are addicted. When administration stops after binge use, it is followed by a "crash", the onset of severely dysphoric mood with escalating exhaustion until sleep is achieved. Resumption of use may occur upon awakening or may not occur for several days, but the intense euphoria such use can, as it has in many users, produce intense craving and develop rather quickly into addiction. The risk of becoming cocaine-dependent within 2 years of first use(recent-onset) is 5-6%; after 10 years, it's 15-16%. These are the aggregate rates for all types of use considered, i.e., smoking, snorting, injecting. Among recent-onset users, the relative rates are higher for smoking (3.4 times) and much higher for injecting (31 times). They also vary, based on other characteristics, such as gender: among recent-onset users, females are 3.3 times more likely to become addicted, compared to males; age: among recent-onset users, those who started using at ages 12 or 13 were 4 times as likely to become addicted, compared to those who started between ages 18 and 20; and race: among recent-onset users, non-Hispanic Blacks are 7 times as likely to become addicted, compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Many habitual abusers develop a transient manic-like condition similar to amphetamine psychosis and schizophrenia, whose symptoms include aggression, severe paranoia, and tactile hallucinations (including the feeling of insects under the skin, or "coke bugs") during binges.

Cocaine has positive reinforcement effects, which refers to the effect that certain stimuli have on behavior. Good feelings become associated with the drug, causing a frequent user to take the drug as a response to bad news or mild depression. This activation strengthens the response that was just made. If the drug was taken by a fast acting route such as injection or inhalation, the response will be the act of taking more cocaine, so the response will be reinforced. Powder cocaine, being a club drug is mostly consumed in the evening and night hours. Because cocaine is a stimulant, a user will often drink large amounts of alcohol during and after usage or smoke cannabis to dull "crash" effects and hasten slumber. Benzodiazepines (e.g., xanax, rohypnol) are also used for this purpose. Other drugs such as heroin and various pharmaceuticals are often used to amplify reinforcement or to minimize such negative effects, further increasing addiction potential and harmfulness.

It has been shown in studies that rhesus monkeys provided with a mechanism of cocaine self-administration prefer the drug over food that is in the cage. This happens even when the monkeys are starving.

It is speculated that cocaine's addictive properties stem partially from its DAT-blocking effects (in particular, increasing the dopaminergic transmission from ventral tegmental area neurons). However, a study has shown that mice with no dopamine transporters still exhibit the rewarding effects of cocaine administration. Later work demonstrated that a combined DAT/SERT knockout eliminated the rewarding effects. The rewarding effects of cocaine are influenced by circadian rhythms, possibly by involving a set of genes termed "clock genes". However, chronic cocaine addiction is not solely due to cocaine reward. Chronic repeated use is needed to produce cocaine-induced changes in brain reward centers and consequent chronic dysphoria (described above under "Effects and Health Issues - Chronic"). Dysphoria magnifies craving for cocaine because cocaine reward rapidly, albeit transiently, improves mood. This contributes to continued use and a self-perpetuating, worsening condition, since those addicted usually cannot appreciate that long-term effects are opposite those occurring immediately after use.

Treatment

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) shows promising results. One or more cocaine vaccines exist or are on trial that will stop desirable effects from the drug. The National Institutes of Health of an unspecified country is researching modafinil, a narcolepsy drug and mild stimulant, as a potential cocaine treatment. Twelve-step programs such as Cocaine Anonymous (modeled on Alcoholics Anonymous) are claimed by many cocaine addicts to be helpful in achieving long-term abstinence. These spiritual programs have no statistically-measurable effect as Alcoholics Anonymous does not release any quantifiable measure of its success rates. There are, however, many recovering addicts who claim this program has aided them.

GVG

Studies have shown that gamma vinyl-gamma-aminobutyric acid (gamma vinyl-GABA, or GVG), a drug normally used to treat epilepsy, blocks cocaine's action in the brains of primates. GVG increases the amount of the neurotransmitter GABA in the brain and reduces the level of dopamine in the region of the brain that is thought to be involved in addiction. In January 2005 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave permission for a Phase I clinical trial of GVG for the treatment of addiction. Another drug currently tested for anti-addictive properties is the cannabinoid antagonist rimonabant.

GBR 12909

GBR 12909 (Vanoxerine) is a selective dopamine uptake inhibitor. Because of this, it reduces cocaine's effect on the brain, and may help to treat cocaine addiction. Studies have shown that GBR, when given to primates, suppresses cocaine self-administration.

Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine (Effexor), although not a dopamine re-uptake inhibitor, is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that has been successfully used to combat the depression caused by cocaine withdrawal and to a lesser extent, the addiction associated with the drug itself. Venlafaxine has been shown to have significant withdrawal problems itself, and can lead to lifetime use due to these withdrawal effects. A statisically significant number of people prescribed Effexor have committed suicide (2 attempts per 1000 patients, vs 1.56 suicides per 1,000 untreated depressives).

Coca teas

Coca herbal tea has been used for the treatment of cocaine dependence. The effects of the coca tea are a nice stimulation and mood lift. It doesn't produce any significant numbing of the mouth nor does it give a rush like snorting cocaine. Much of the effect of coca seems to come from the secondary alkaloids, as it is not only quantitatively different from pure cocaine but also qualitatively different. In one study, coca tea was used—in addition to counseling—to treat 23 addicted coca-paste smokers in Lima, Peru. Relapses fell from an average of 4.35 times per month before treatment with coca tea to 1.22 during the treatment. Abstinence length increased from an average of 32 days prior to treatment to 217.2 days during treatment. These results suggest that coca tea is an effective method for preventing relapse during treatment for cocaine addiction.

Legal status

Main article: Legal status of cocaineThe production, the distribution and the sale of cocaine products is restricted (and illegal in most contexts) in most countries. Since 1914, when The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act passed in the U.S., cocaine has been considered a ‘hard drug.' In Colombia, the indigenous population is allowed to grow coca for traditional reasons. All other coca is considered part of the illegal black market. In parts of Africa, it is a crime to be in possession of cocaine or even be seen with it. In South America, cultivation of coca is allowed only with special permission; however, it is a crime to posses processed cocaine. Some parts of Europe and Australia allow processed cocaine for medicinal uses only. Also, in some parts of the Middle East and Asia, being in possession of cocaine can be punishable by death.

Usage

| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the United States

Overall usage

In the late 1800's, many authors of this time, including Freud, openly admitted to going on cocaine binges to complete their works. But at the turn of the twentieth century, the dangers of cocaine were becoming apparent and the public did not want a society of drug addicts. There was a public outcry against the use and abuse of cocaine. Groups were demonizing cocaine users as the low-lifes of society. There was also a racial backlash, and many people blamed the African American community.

During the 60's cocaine had become mainstream again, yet it was still illegal. Prices of cocaine began to rise, and those of the lower class could no longer afford their addiction. Cocaine has become the second most popular illegal recreational drug in the U.S. Cocaine is generally used by privileged middle to upper class communities. It is also popular amongst college students, not just to aide in studying, but also as a party drug. Its users span over different ages, races, and professions. In the 1970's and 80's the drug became particularly popular in the disco culture as cocaine usage was very common and popular in many discos such as Studio 54.

The National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) reported in 1999 that cocaine was used by 3.7 million Americans, or 1.7 percent of the household population age 12 and older. Estimates of the current number of those who use cocaine regularly (at least once per month) vary, but 1.5 million is a widely accepted figure within the research community.

Although cocaine use had not significantly changed over the six years prior to 1999, the number of first-time users went up from 574,000 in 1991, to 934,000 in 1998 — an increase of 63%. While these numbers indicated that cocaine is still widely present in the United States, cocaine use was significantly less prevalent than it was during the early 1980s. Cocaine use peaked in 1982 when 10.4 million Americans (5.6 percent of the population) reportedly used the drug.

Usage among youth

The 1999 Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey found the proportion of American students reporting use of powder cocaine rose during the 1990s. In 1991, 2.3 percent of eighth-graders stated that they had used cocaine in their lifetime. This figure rose to 4.7 percent in 1999. For the older grades, increases began in 1992 and continued through the beginning of 1999. Between those years, lifetime use of cocaine went from 3.3 percent to 7.7 percent for tenth-graders and from 6.1 percent to 9.8 percent for twelfth-graders. Lifetime use of crack cocaine, according to MTF, also increased among eighth-, tenth-, and twelfth-graders, from an average of 2 percent in 1991 to 3.9 percent in 1999.

Perceived risk and disapproval of cocaine and crack use both decreased during the 1990s at all three grade levels. The 1999 NHSDA found the highest rate of monthly cocaine use was for those aged 18–25 at 1.7 percent, an increase from 1.2 percent in 1997. Rates declined between 1996 and 1998 for ages 26–34, while rates slightly increased for the 12–17 and 35+ age groups. Studies also show people are experimenting with cocaine at younger ages. NHSDA found a steady decline in the mean age of first use from 23.6 years in 1992 to 20.6 years in 1998.

Availability

Cocaine is readily available in all major countries' metropolitan areas. According to the Summer 1998 Pulse Check, published by the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy, cocaine use had stabilized across the country, with a few increases reported in San Diego, Bridgeport, Miami, and Boston. In the West, cocaine usage was lower, which was thought to be because some users were switching to methamphetamine, which was cheaper and provides a longer-lasting high. Numbers of cocaine users are still very large, with a concentration among city-dwelling youth.

Cocaine is typically sold to users by the gram ($40-$80US) or eight ball (3.5 grams, or roughly 1/8th oz; hence the term "eight ball") ($100-$250). Quality and price can vary dramatically depending on demand and supply.

References

- ^ Pagliaro, Louis (2004). Pagliaros’ Comprehensive Guide to Drugs and Substances of Abuse. Washington, D.C.: American Pharmacists Association. ISBN 1-58212-066-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Altman AJ, Albert DM, Fournier GA (1985). "Cocaine's use in ophthalmology: our 100-year heritage". Surv Ophthalmol. 29: 300–307.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - A. Barnett, R. Hawks, and R. Resnick (1981). "Cocaine Pharmacokinetics in Humans". The Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 3: 353–366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - A. Weil (1981). "The Therapeutic Value of Coca in Contemporary Medicine". The Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 3: 367–376.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Gay GR, Inaba DS, Sheppard CW and Newmyer JA (1975). "Cocaine: History, epidemiology, human pharmacology and treatment. A perspective on a new debut for an old girl". Clinical Toxicology. 8: 149–178.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Monardes, Nicholas (1925). Joyfull Newes out of the Newe Founde Worlde. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Yentis SM, Vlassakov KV (1999). "Vassily von Anrep, forgotten pioneer of regional anesthesia". Anesthesiology. 90: 890–895.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Halsted W (1885). "Practical comments on the use and abuse of cocaine". New York Medical Journal. 42: 294–295.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Corning JL (1885). "An experimental study". New York Medical Journal. 42: 483.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - ^ Streatfeild, Dominic (2003). Cocaine: An Unauthorized Biography. Picador. ISBN 0-312-42226-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - WHO/UNICRI (1995). "WHO Cocaine Project".

- News article (1995). "Report paints picture of global use of cocaine". British Medical Journal.

- – Pee Wee Herman in "The Thrill Can Kill"

- dea.gov

- Siegel RK, Elsohly MA, Plowman T, Rury PM, Jones RT (January 3, 1986). "Cocaine in herbal tea". Journal of the American Medical Association. 255 (1): 40.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Volkow ND; et al. (2000). "Effects of route of administration on cocaine induced dopamine transporter blockade in the human brain". PMID 10983846.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Dimitrijevic N, Dzitoyeva S, Manev H (2004). "An automated assay of the behavioral effects of cocaine injections in adult Drosophila". J Neurosci Methods. 137 (2): 181–184.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Uz T, Akhisaroglu M, Ahmed R, Manev H (2003). "The pineal gland is critical for circadian Period1 expression in the striatum and for circadian cocaine sensitization in mice". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (12): 2117–23. PMID 12865893.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McClung C, Sidiropoulou K, Vitaterna M, Takahashi J, White F, Cooper D, Nestler E (2005). "Regulation of dopaminergic transmission and cocaine reward by the Clock gene". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102 (26): 9377–81. PMID 15967985.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bedford JA, Turner CE, Elsohly HN (1982). "Comparative lethality of coca and cocaine". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 17 (5): 1087–1088.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - scienceblog.com

- Trozak D, Gould W (1984). "Cocaine abuse and connective tissue disease". J Am Acad Dermatol. 10 (3): 525. PMID 6725666.

- karger.com

- jnnp.bmjjournals.com

- cjasn.asnjournals.org

- ndt.oxfordjournals.org

- NDIC (2006). "National Drug Threat Assessment 2006".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence (1999). "Australian Illicit Drug Report 1998–99" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - ^ Macko, Steve (Friday, July 17, 1998). "Colombia's new breed of drug trafficker". Emergency Response and Research Institute, Chicago.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - O'Brien MS, Anthony JC (2005). "Risk of becoming cocaine dependent: epidemiological estimates for the United States, 2000-2001". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30: 1006–1018. PMID 15785780.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Gawin. FH. (1991). "Cocaine addiction: Psychology and neurophysiology". Science. 251: 1580–1586.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Aigner TG, Balster RL. "Choice behavior in rhesus monkeys: cocaine versus food". Science 201: 534–535.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - Sora; et al. (June 23, 1998). "Cocaine reward models: Conditioned place preference can be established in dopamine- and in serotonin-transporter knockout mice". PNAS. 95 (13): 7600–7704.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Sora; et al. (April 24, 2001). "Molecular mechanisms of cocaine reward: Combined dopamine and serotonin transporter knockouts eliminate cocaine place preference". PNAS. 98 (9): 5300–5305.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Kurtuncu; et al. (April 12, 2004). "Involvement of the pineal gland in diurnal cocaine reward in mice". European Journal of Pharmacology. 489 (3): 203–205.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Yuferov; et al. (October 2005). "Biological clock: biological clocks may modulate drug addiction". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (10): 1101–1103.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Teobaldo, Llosa (1994). "The Standard Low Dose of Oral Cocaine: Used for Treatment of Cocaine Dependence". Substance Abuse. 15 (4): 215–220.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - cocaineaddictiondrugrehab.com

- erowid.org

See also

- Benzocaine

- Coca

- Coca eradication

- Crack baby

- Crack Cocaine and Hip Hop

- Crack Epidemic

- Cuscohygrine

- Drug addiction

- Drug injection

- Drugs and prostitution

- Ecgonine benzoate

- List of celebrity cocaine addicts

- Hydroxytropacocaine

- Hygrine

- Methylecgonine cinnamate

- Novocaine

- Psychoactive drug

- (-)-2-ß-Carbomethoxy-3-ß-(4-fluorophenyl)tropane naphthalenedisulfonate (CFT, WIN-35,428)

- Tropacocaine

- Truxilline

- Dihydrocuscohygrine

Further reading

- Cocaine: an unauthorized biography by Dominic Streatfeild

- Über Coca by Sigmund Freud

- History of Coca. The Divine Plant of the Incas" by W. Golden Mortimer, M.D. 576 pp. And/Or Press San Francisco, 1974. No ISBN.

- The Triumph of Surgery by Jürgen Thorwald - Ch. 6 - The second battle against Pain (The early use of cocaine solution in eye surgery)

- Snowblind by Robert Sabbag

- The Man Who Made It Snow by Max Mermelstein. ISBN 0-671-70312-9

- Celerino III Castillo & Dave Harmon (1994). Powderburns: Cocaine, Contras & the Drug War, Sundial. ISBN 0-88962-578-6 (paperback) ISBN 0-8095-4855-0 (hardcover; Borgo Pr; 3rd ed.; 1995).

- Alexander Cockburn & Jeffrey St. Clair (1999). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press, Verso. ISBN 1-85984-139-2 (cloth), ISBN 1-85984-258-5 (paperback). Cites 116 books.

- Frederick P. Hitz (1999). Obscuring Propriety: The CIA and Drugs, International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 12(4): 448-462 DOI:10.1080/088506099304990

- Robert Parry (1999). Lost History: Contras, Cocaine, the Press & “Project Truth”, Media Consortium. ISBN 1-893517-00-4.

- Richard Smart (Hard Cover 1985). The Snow Papers The Atlantic Monthly Press ISBN 0-87113-030-0

- Peter Dale Scott & Jonathan Marshall (1991). Cocaine Politics: Drugs, Armies, and the CIA in Central America, University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21449-8 (paperback, 1998 reprint), ISBN 0-520-07312-6 (hardcover, 1991), ISBN 0-520-07781-4 (paperback, 1992 reprint).

- Gary Webb(1998). Dark Alliance: The CIA, the Contras, and the Crack Cocaine Explosion, Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1-888363-68-1 (hardcover, 1998), ISBN 1-888363-93-2 (paperback, 1999).

- Philippe Bourgois In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2003. Second Updated Edition.

- Otto Snow THC & Tropacocaine ISBN 0-9663128-5-6 (paperback 2004)

- David Lee Cocaine Handbook ISBN 0-915904-56-X (paperback 1981)

- Adam Gottlieb Cocaine Tester's Handbook ASIN B0007C137A (paperback 1975)

- Adam Gottlieb Pleasures of Cocaine: If You Enjoy: This Book May Save Your Life ISBN 0-914171-81-X (paperback 1996)

- Carol Saline Doctor Snow: How the FBI Nailed a Ivy League Coke King ISBN 0-453-00593-4 (HardCover 1986)

- Mark Bowden Doctor Dealer: The Rise & Fall Of An All American Boy and his Multi-Million Dollar Cocaine Empire ISBN 0-446-51382-2 (HardCover 1987)

External links

| This article's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- — How cocaine is made, presumably from within Central/South America (video)

- Self-test — from Cocaine Addicts Anonymous

- Cocaine User Helping Hand — Internet Portal dedicated to help crack- and cocaine-addicted people. Contains wide variety of information on drug abuse, available treatment, and recovery issues.

- The Erowid Cocaine Vault

- Urban Legends Reference Pages: Cokelore (Cocaine-Cola) — information about cocaine in Coke

- Addictive properties

- Shared Responsibility — Information about European cocaine use and drug trafficking in Colombia.

- Cocaine content of plants

- Cocaine.org — Information guide on Cocaine and its history, use/abuse, etc.

- Cocaine - The History and the Risks at h2g2

- Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence by the WHO – Summary by GreenFacts