| Revision as of 21:10, 15 May 2016 view sourceBrandmeister (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers38,018 edits →top: wikilink← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:11, 15 May 2016 view source Potguru (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,102 edits merger proposalNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{mergeto|Cannabis|discuss=Talk:Cannabis#proposed_merger|date=May 2016}} | |||

| {{redirect|Marijuana}} | {{redirect|Marijuana}} | ||

| {{Pp-move-indef}} | {{Pp-move-indef}} | ||

Revision as of 22:11, 15 May 2016

| It has been suggested that this article be merged into Cannabis. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2016. |

| Cannabis | |

|---|---|

A flowering cannabis plant A flowering cannabis plant | |

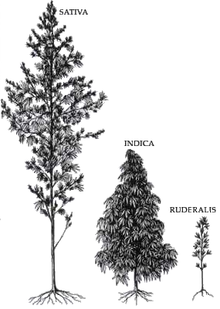

| Source plant(s) | Cannabis sativa, Cannabis sativa forma indica, Cannabis ruderalis |

| Part(s) of plant | flower |

| Geographic origin | Central and South Asia |

| Active ingredients | Tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol, cannabinol, tetrahydrocannabivarin |

| Main producers | Afghanistan, Canada, China, Colombia, India, Jamaica, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, Pakistan, Paraguay, Spain, Thailand, Turkey, United States |

| Legal status |

|

Cannabis, also known as marijuana among other names, is a preparation of the Cannabis plant intended for use as a psychoactive drug or medicine. The main psychoactive part of cannabis is tetrahydrocannabinol (THC); one of 483 known compounds in the plant, including at least 65 other cannabinoids. Cannabis can be used by smoking, vaporization, within food, or as an extract.

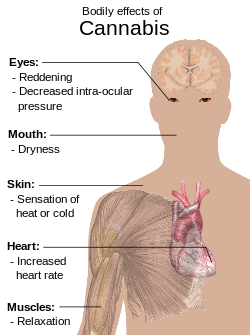

Cannabis is often used for its mental and physical effects, such as a "high" or "stoned" feeling, a general change in perception, heightened mood, and an increase in appetite. Short term side effects may include a decrease in short-term memory, dry mouth, impaired motor skills, red eyes, and feelings of paranoia or anxiety. Long term side effects may include addiction, decreased mental ability in those who started as teenagers, and behavioral problems in children whose mothers used cannabis during pregnancy. Onset of effects is within minutes when smoked and about 30 to 60 minutes when cooked and eaten. They last for between two and six hours.

Cannabis is mostly used recreationally or as a medicinal drug. It may also be used for religious or spiritual purposes. In 2013, between 128 and 232 million people used cannabis (2.7% to 4.9% of the global population between the ages of 15 and 65). In 2015, 43% of Americans had used cannabis which increased to 51% in 2016. About 12% have used it in the past year, and 7.3% have used it in the past month. This makes it the most commonly used illegal drug both in the world and the United States.

The earliest recorded uses date from the 3rd millennium BC. Since the early 20th century, cannabis has been subject to legal restrictions, with the having, use, and sale of cannabis preparations containing psychoactive cannabinoids illegal in most countries of the world. Medical cannabis refers to the physician-recommended use of cannabis, which is taking place in Canada, Belgium, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, and 23 U.S. states. Cannabis use started to become popular in the US in the 1970s. Support for legalization has increased in the United States and several US states have legalized recreational or medical use.

Uses

Medical

Main article: Medical cannabisCannabis is used to reduce nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, to improve appetite in people with HIV/AIDS, to treat chronic pain, and help with muscle spasms. Its use for other medical applications is insufficient for conclusions about safety or efficacy. Short-term use increases minor adverse effects, but does not appear to increase major adverse effects. Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear, and there are concerns including memory and cognition problems, risk for addiction, risk of schizophrenia among young people, and the risk of children taking it by accident.

The medicinal value of cannabis is disputed. The American Society of Addiction Medicine dismisses medical use because of concerns about dependence and adverse health effects. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that cannabis is associated with numerous harmful health effects, and that significant aspects such as content, production, and supply are unregulated. The FDA approves of the prescription of two products (not for smoking) that have pure THC in a small controlled dose as the active substance.

Recreational

Main article: Effects of cannabis

Cannabis has psychoactive and physiological effects when consumed. The immediate desired effects from consuming cannabis include relaxation and euphoria (the "high" or "stoned" feeling), a general alteration of conscious perception, increased awareness of sensation, increased libido and distortions in the perception of time and space. At higher doses, effects can include altered body image, auditory and/or visual illusions, pseudohallucinations and ataxia from selective impairment of polysynaptic reflexes. In some cases, cannabis can lead to dissociative states such as depersonalization and derealization.

Some immediate undesired side effects include a decrease in short-term memory, dry mouth, impaired motor skills and reddening of the eyes. Aside from a subjective change in perception and mood, the most common short-term physical and neurological effects include increased heart rate, increased appetite and consumption of food, lowered blood pressure, impairment of short-term and working memory, psychomotor coordination, and concentration. Some users may experience an episode of acute psychosis, which usually abates after 6 hours, but in rare instances heavy users may find the symptoms continuing for many days.

Spiritual

Main article: Entheogenic use of cannabis

Cannabis has held sacred status in several religions. It has been used in an entheogenic context – a chemical substance used in a religious, shamanic, or spiritual context - in India and Nepal since the Vedic period dating back to approximately 1500 BCE, but perhaps as far back as 2000 BCE. There are several references in Greek mythology to a powerful drug that eliminated anguish and sorrow. Herodotus wrote about early ceremonial practices by the Scythians, thought to have occurred from the 5th to 2nd century BCE. Itinerant Hindu saints have used it in Nepal and India for centuries. In modern culture the spiritual use of cannabis has been spread by the disciples of the Rastafari movement who use cannabis as a sacrament and as an aid to meditation. The earliest known reports regarding the sacred status of cannabis in India and Nepal come from the Atharva Veda estimated to have been written sometime around 2000–1400 BCE.

Available forms

Main article: Cannabis consumption

Cannabis is consumed in many different ways:

- smoking, which typically involves burning and inhaling vaporized cannabinoids ("smoke") from small pipes, bongs (portable versions of hookahs with a water chamber), paper-wrapped joints or tobacco-leaf-wrapped blunts, and other items.

- vaporizer, which heats any form of cannabis to 165–190 °C (329–374 °F), causing the active ingredients to evaporate into a vapor without burning the plant material (the boiling point of THC is 157 °C (315 °F) at 760 mmHg pressure).

- cannabis tea, which contains relatively small concentrations of THC because THC is an oil (lipophilic) and is only slightly water-soluble (with a solubility of 2.8 mg per liter). Cannabis tea is made by first adding a saturated fat to hot water (e.g. cream or any milk except skim) with a small amount of cannabis.

- edibles, where cannabis is added as an ingredient to one of a variety of foods, including butter and baked goods.

Adverse effects

Main article: Long-term effects of cannabis Further information: Cannabis in pregnancy

According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services, there were 455,000 emergency room visits associated with cannabis use in 2011. These statistics include visits in which the patient was treated for a condition induced by or related to recent cannabis use. The drug use must be "implicated" in the emergency department visit, but does not need to be the direct cause of the visit. Most of the illicit drug emergency room visits involved multiple drugs. In 129,000 cases, cannabis was the only implicated drug.

Heavy, long term exposure to marijuana may have biologically-based physical, mental, behavioral and social health consequences and may be "associated with diseases of the liver (particularly with co-existing hepatitis C), lungs, heart, and vasculature". It is recommended that cannabis use be stopped before and during pregnancy as it can result in negative outcomes for both the mother and baby. A 2014 review found that while cannabis use may be less harmful than alcohol use, the recommendation to substitute it for problematic drinking is premature without further study.

Toxicity

THC, the principal psychoactive constituent of the cannabis plant, has low toxicity. The dose of THC needed to kill 50% of tested rodents is extremely high. Acute effects may include anxiety and panic, impaired attention, and memory (while intoxicated), an increased risk of psychotic symptoms, and possibly an increased risk of accidents if a person drives a motor vehicle while intoxicated. Short-term Cannabis intoxication can hinder the mental processes of organizing and collecting thoughts. This condition is known as temporal disintegration. Psychotic episodes are well-documented and typically resolve within minutes or hours. There have been few reports of symptoms lasting longer. Cannabis has not been reported to cause fatal overdose. Studies have found that cannabis use during adolescence is associated with impairments in memory that persist beyond short-term intoxication.

Lungs

There has been a limited amount of studies that have looked at the effects of smoking cannabis on the respiratory system. Chronic heavy marijuana smoking is associated with coughing, production of sputum, wheezing, and other symptoms of chronic bronchitis. Regular cannabis use has not been shown to cause significant abnormalities in lung function. Short-term use of cannabis is associated with bronchodilation.

Cancer

Cannabis smoke contains thousands of organic and inorganic chemical compounds. This tar is chemically similar to that found in tobacco smoke, and over fifty known carcinogens have been identified in cannabis smoke, including; nitrosamines, reactive aldehydes, and polycylic hydrocarbons, including benzpyrene. Cannabis smoke is also inhaled more deeply than is tobacco smoke. As of 2015, there is no consensus regarding whether cannabis smoking is associated with an increased risk of cancer. Light and moderate use of cannabis is not believed to increase risk of lung or upper airway cancer. Evidence for causing these cancers is mixed concerning heavy, long-term use. In general there are far lower risks of pulmonary complications for regular cannabis smokers when compared with those of tobacco. A 2015 review found an association between cannabis use and the development of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs), particularly non-seminoma TGCTs. Combustion products are not present when using a vaporizer, consuming THC in pill form, or consuming cannabis foods.

Cardiovascular

There is serious suspicion among cardiologists, spurring research but falling short of definitive proof, that cannabis use has the potential to contribute to cardiovascular disease. Cannabis is believed to be an aggravating factor in rare cases of arteritis, a serious condition that in some cases leads to amputation. Because 97% of case-reports also smoked tobacco, a formal association with cannabis could not be made. If cannabis arteritis turns out to be a distinct clinical entity, it might be the consequence of vasoconstrictor activity observed from delta-8-THC and delta-9-THC. Other serious cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction, stroke, sudden cardiac death, and cardiomyopathy have been reported to be temporally associated with cannabis use. Research in these events is complicated because cannabis is often used in conjunction with tobacco, and drugs such as alcohol and cocaine. These putative effects can be taken in context of a wide range of cardiovascular phenomena regulated by the endocannabinoid system and an overall role of cannabis in causing decreased peripheral resistance and increased cardiac output, which potentially could pose a threat to those with cardiovascular disease. There is some evidence from case reports that cannabis use may provoke fatal cardiovascular events in young people who have not been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. Smoking cannabis has also been shown to increase the risk of myocardial infarction by 4.8 times for the 60 minutes after consumption.

Neurological

A 2013 review comparing different structural and functional imaging studies showed morphological brain alterations in long-term cannabis users which were found to possibly correlate to cannabis exposure. A 2010 review found resting blood flow to be lower globally and in prefrontal areas of the brain in cannabis users, when compared to non-users. It was also shown that giving THC or cannabis correlated with increased bloodflow in these areas, and facilitated activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and frontal cortex when participants were presented with assignments demanding use of cognitive capacity. Both reviews noted that some of the studies that they examined had methodological limitations, for example small sample sizes or not distinguishing adequately between cannabis and alcohol consumption. A 2011 review found that cannabis use impaired cognitive functions on several levels, ranging from basic coordination to executive function tasks. A 2013 review found that cannabis users consistently had smaller hippocampi than nonusers, but noted limitations in the studies analyzed such as small sample sizes and heterogeneity across studies. A 2012 meta-analysis found that the effects of cannabis use on neurocognitive functions were "limited to the first 25 days of abstinence" and that there was no evidence that such use had long-lasting effects. A 2015 review found that cannabis use was associated with neuroanatomic alterations in brain regions rich in cannabinoid receptors, such as the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and cerebellum. The same review found that greater dose of marijuana and earlier age at onset of use were also associated with such alterations. There is limited evidence that chronic cannabis use can reduce levels of glutamate metabolites in the human brain.

It is not clear whether cannabis use affects the rate of suicide.

Chronic use

Effects of chronic use may include bronchitis, a cannabis dependence syndrome, and subtle impairments of attention and memory. These deficits persist while chronically intoxicated. There is little evidence that cognitive impairments persist in adult abstinent cannabis users. Compared to non-smokers, people who smoked cannabis regularly in adolescence exhibit reduced connectivity in specific brain regions associated with memory, learning, alertness, and executive function. A study has suggested that sustained heavy, daily, adolescent onset cannabis use over decades is associated with a decline in IQ by age 38. No effects were found in those who initiated cannabis use later, or in those who ceased use earlier in adulthood.

Tolerance and withdrawal

Main article: Cannabis dependenceCannabis usually causes no tolerance or withdrawal symptoms except in heavy users. In a survey of heavy users 42.4% experienced withdrawal symptoms when they tried to quit marijuana such as craving, irritability, boredom, anxiety and sleep disturbances. About 9% of those who experiment with marijuana eventually become dependent. The rate goes up to 1 in 6 among those who begin use as adolescents, and one quarter to one-half of those who use it daily according to a NIDA review. A 2013 review estimates daily use is associated with a 10-20% rate of dependence. The highest risk of cannabis dependence is found in those with a history of poor academic achievement, deviant behavior in childhood and adolescence, rebelliousness, poor parental relationships, or a parental history of drug and alcohol problems. Cannabis withdrawal is less severe than withdrawal from alcohol.

Motor vehicle crashes

A 2012 meta-analysis found that cannabis use was associated with an increased risk of being involved in a motor vehicle crash. A 2016 review also found a statistically significant increase in crash risk associated with marijuana use, but noted that this risk was "of low to medium magnitude." The increase in risk of motor vehicle crash for cannabis use is between 2 and 3 times relative to baseline, whereas that for comparable doses of alcohol is between 6 and 15 times.

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

See also: Effects of cannabis § Biochemical mechanisms in the brainThe high lipid-solubility of cannabinoids results in their persisting in the body for long periods of time. Even after a single administration of THC, detectable levels of THC can be found in the body for weeks or longer (depending on the amount administered and the sensitivity of the assessment method). A number of investigators have suggested that this is an important factor in marijuana's effects, perhaps because cannabinoids may accumulate in the body, particularly in the lipid membranes of neurons.

Not until the end of the 20th century was the specific mechanism of action of THC at the neuronal level studied. Researchers have subsequently confirmed that THC exerts its most prominent effects via its actions on two types of cannabinoid receptors, the CB1 receptor and the CB2 receptor, both of which are G-protein coupled receptors. The CB1 receptor is found primarily in the brain as well as in some peripheral tissues, and the CB2 receptor is found primarily in peripheral tissues, but is also expressed in neuroglial cells. THC appears to alter mood and cognition through its agonist actions on the CB1 receptors, which inhibit a secondary messenger system (adenylate cyclase) in a dose dependent manner. These actions can be blocked by the selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (rimonabant), which has been shown in clinical trials to be an effective treatment for smoking cessation, weight loss, and as a means of controlling or reducing metabolic syndrome risk factors. However, due to the dysphoric effect of CB1 antagonists, this drug is often discontinued due to these side effects.

Via CB1 activation, THC indirectly increases dopamine release and produces psychotropic effects. Cannabidiol also acts as an allosteric modulator of the mu and delta opioid receptors. THC also potentiates the effects of the glycine receptors. The role of these interactions in the "marijuana high" remains elusive.

Physical and chemical properties

Detection in body fluids

Main article: Cannabis drug testingTHC and its major (inactive) metabolite, THC-COOH, can be measured in blood, urine, hair, oral fluid or sweat using chromatographic techniques as part of a drug use testing program or a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal offense. The concentrations obtained from such analyses can often be helpful in distinguishing active use from passive exposure, elapsed time since use, and extent or duration of use. These tests cannot, however, distinguish authorized cannabis smoking for medical purposes from unauthorized recreational smoking. Commercial cannabinoid immunoassays, often employed as the initial screening method when testing physiological specimens for marijuana presence, have different degrees of cross-reactivity with THC and its metabolites. Urine contains predominantly THC-COOH, while hair, oral fluid and sweat contain primarily THC. Blood may contain both substances, with the relative amounts dependent on the recency and extent of usage.

The Duquenois–Levine test is commonly used as a screening test in the field, but it cannot definitively confirm the presence of cannabis, as a large range of substances have been shown to give false positives. Despite this, it is common in the United States for prosecutors to seek plea bargains on the basis of positive D–L tests, claiming them definitive, or even to seek conviction without the use of gas chromatography confirmation, which can only be done in the lab. In 2011, researchers at John Jay College of Criminal Justice reported that dietary zinc supplements can mask the presence of THC and other drugs in urine. However, a 2013 study conducted by researchers at the University of Utah School of Medicine refute the possibility of self-administered zinc producing false-negative urine drug tests.

Varieties and strains

CBD is a 5-HT1A receptor agonist, which may also contribute to an anxiolytic effect. This likely means the high concentrations of CBD found in Cannabis indica mitigate the anxiogenic effect of THC significantly. The effects of sativa are well known for their cerebral high, hence its daytime use as medical cannabis, while indica is well known for its sedative effects and preferred night time use as medical cannabis.

Psychoactive ingredients

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), "the amount of THC present in a cannabis sample is generally used as a measure of cannabis potency." The three main forms of cannabis products are the flower, resin (hashish), and oil (hash oil). The UNODC states that cannabis often contains 5% THC content, resin "can contain up to 20% THC content", and that "Cannabis oil may contain more than 60% THC content."

A 2012 review found that the THC content in marijuana had increased worldwide from 1970 to 2009. It is unclear, however, whether the increase in THC content has caused people to consume more THC or if users adjust based on the potency of the cannabis. It is likely that the higher THC content allows people to ingest less tar. At the same time Cannabidiol (CBD) levels in seized samples have lowered, in part because of the desire to produce higher THC levels and because more illegal growers cultivate indoors using artificial lights. This helps avoid detection but reduces the CBD production of the plant.

Australia's National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre (NCPIC) states that the buds (flowers) of the female cannabis plant contain the highest concentration of THC, followed by the leaves. The stalks and seeds have "much lower THC levels". The UN states that leaves can contain ten times less THC than the buds, and the stalks one hundred times less THC.

After revisions to cannabis rescheduling in the UK, the government moved cannabis back from a class C to a class B drug. A purported reason was the appearance of high potency cannabis. They believe skunk accounts for between 70 and 80% of samples seized by police (despite the fact that skunk can sometimes be incorrectly mistaken for all types of herbal cannabis). Extracts such as hashish and hash oil typically contain more THC than high potency cannabis flowers.

Preparations

-

Dried flower buds

Dried flower buds

-

Kief

Kief

-

Hashish

Hashish

-

Tincture

Tincture

-

Hash oil

Hash oil

-

Infusion (dairy butter)

-

Pipe resin

Pipe resin

-

A forced-air vaporizer. The detachable balloon fills with vapors

A forced-air vaporizer. The detachable balloon fills with vapors

Marijuana

Marijuana or marihuana (herbal cannabis), consists of the dried flowers and subtending leaves and stems of the female Cannabis plant. This is the most widely consumed form, containing 3% to 20% THC, with reports of up-to 33% THC. In contrast, cannabis varieties used to produce industrial hemp contain less than 1% THC and are thus not valued for recreational use.

This is the stock material from which all other preparations are derived. It is noted that cannabis or its extracts must be sufficiently heated or dehydrated to cause decarboxylation of its most abundant cannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), into psychoactive THC.

Kief

Main article: KiefKief is a powder, rich in trichomes, which can be sifted from the leaves and flowers of cannabis plants and either consumed in powder form or compressed to produce cakes of hashish. The word "kif" derives from colloquial Arabic كيف kēf/kīf, meaning pleasure.

Hashish

Main article: HashishHashish (also spelled hasheesh, hashisha, or simply hash) is a concentrated resin cake or ball produced from pressed kief, the detached trichomes and fine material that falls off cannabis flowers and leaves. or from scraping the resin from the surface of the plants and rolling it into balls. It varies in color from black to golden brown depending upon purity and variety of cultivar it was obtained from. It can be consumed orally or smoked, and is also vaporised, or 'vaped'. The term "Rosin Hash" refers to a high quality solventless product obtained through heat and pressure.

Tincture

Main article: Tincture of cannabisCannabinoids can be extracted from cannabis plant matter using high-proof spirits (often grain alcohol) to create a tincture, often referred to as "green dragon". Nabiximols is a branded product name from a tincture manufacturing pharmaceutical company.

Hash oil

Main article: Hash oilHash oil is a resinous matrix of cannabinoids obtained from the Cannabis plant by solvent extraction, formed into a hardened or viscous mass.

Hash oil can be the most potent of the main cannabis products because of its high level of psychoactive compound per its volume, which can vary depending on the plant's mix of essential oils and psychoactive compounds. Butane and supercritical carbon dioxide hash oil have become popular in recent years.

Infusions

There are many varieties of cannabis infusions owing to the variety of non-volatile solvents used. The plant material is mixed with the solvent and then pressed and filtered to express the oils of the plant into the solvent. Examples of solvents used in this process are cocoa butter, dairy butter, cooking oil, glycerine, and skin moisturizers. Depending on the solvent, these may be used in cannabis foods or applied topically.

Adulterated cannabis

Contaminants or adulterants may be found in marijuana or hashish. Other substances may be added to cannabis to add weight to the product (lead has been used in some cases), to increase its psychoactive effects (e.g., Phencyclidine), or as part of the cultivation and processing of the cannabis (e.g., fertilizer). Hashish obtained from "soap bar"-type sources. The dried flowers of the plant may be contaminated by the plant taking up heavy metals and other toxins from its growing environment, or by the addition of glass. In the Netherlands, chalk has been used to make cannabis appear to be of a higher quality. Increasing the weight of hashish products in Germany with lead caused lead intoxication in at least 29 users.

Despite cannabis being generally perceived as a natural product, in a recent Australian survey one in four Australians consider cannabis grown indoors under hydroponic conditions to be a greater health risk due to increased contamination, added to the plant during cultivation to enhance the plant growth and quality.

Drug dealers may "spike" or lace marijuana with other chemicals such as PCP, creating a product known as "wet marijuana"; this enhances the effects of smoking it and it can be used to make low-grade, low-potency marijuana seem more effective.

Medical use

Further information: Medical cannabisMedical marijuana refers to the use of the Cannabis plant as a physician-recommended herbal therapy as well as synthetic THC and cannabinoids. So far, the medical use of cannabis is legal only in a limited number of territories, including Canada, Belgium, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, and several U.S. states. This usage generally requires a prescription, and distribution is usually done within a framework defined by local laws. There is evidence supporting the use of cannabis or its derivatives in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, neuropathic pain, and multiple sclerosis. Lower levels of evidence support its use for AIDS wasting syndrome, epilepsy, rheumatoid arthritis, and glaucoma.

History

See also: War on Drugs, Legal history of cannabis in the United States, and History of medical cannabis

Cannabis is indigenous to Central and South Asia. There is evidence of inhalation of cannabis smoke from the 3rd millennium BCE, namely charred cannabis seeds found in a ritual brazier at an ancient burial site in present-day Romania. In 2003, a leather basket filled with cannabis leaf fragments and seeds was found next to a 2,500- to 2,800-year-old mummified shaman in the northwestern Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China. Evidence of cannabis consumption was also found in Egyptian mummies dated about 950 BC.

Cannabis was also used by the ancient Hindus of India and Nepal thousands of years ago. The herb is called ganja (Template:Lang-sa, IAST: gañjā) or ganjika in Sanskrit and other modern Indo-Aryan languages. Some scholars suggest that the ancient drug soma, mentioned in the Vedas, was cannabis, although this theory is disputed.

Cannabis was also known to the ancient Assyrians, who discovered its psychoactive properties through the Aryans. Using it in some religious ceremonies, they called it qunubu (meaning "way to produce smoke"), a probable origin of the modern word "cannabis". The Aryans also introduced cannabis to the Scythians, Thracians and Dacians, whose shamans (the kapnobatai—"those who walk on smoke/clouds") burned cannabis flowers to induce trance.

Cannabis has an ancient history of ritual use and is found in pharmacological cults around the world. Hemp seeds discovered by archaeologists at Pazyryk suggest early ceremonial practices like eating by the Scythians occurred during the 5th to 2nd century BCE, confirming previous historical reports by Herodotus. It was used by Muslims in various Sufi orders as early as the Mamluk period, for example by the Qalandars.

A study published in the South African Journal of Science showed that "pipes dug up from the garden of Shakespeare's home in Stratford-upon-Avon contain traces of cannabis." The chemical analysis was carried out after researchers hypothesized that the "noted weed" mentioned in Sonnet 76 and the "journey in my head" from Sonnet 27 could be references to cannabis and the use thereof. Examples of classic literature featuring cannabis include Les paradis artificiels by Charles Baudelaire and The Hasheesh Eater by Fitz Hugh Ludlow.

John Gregory Bourke described use of "mariguan", which he identifies as Cannabis indica or Indian hemp, by Mexican residents of the Rio Grande region of Texas in 1894. He described its uses for treatment of asthma, to expedite delivery, to keep away witches, and as a love-philtre. He also wrote that many Mexicans added the herb to their cigarritos or mescal, often taking a bite of sugar afterward to intensify the effect. Bourke wrote that because it was often used in a mixture with toloachi (which he inaccurately describes as Datura stramonium), mariguan was one of several plants known as "loco weed". Bourke compared mariguan to hasheesh, which he called "one of the greatest curses of the East", citing reports that users "become maniacs and are apt to commit all sorts of acts of violence and murder", causing degeneration of the body and an idiotic appearance, and mentioned laws against sale of hasheesh "in most Eastern countries".

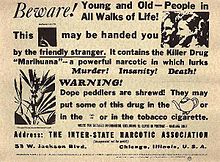

Cannabis was criminalized in various countries beginning in the early 20th century. In the United States, the first restrictions for sale of cannabis came in 1906 (in District of Columbia). It was outlawed in South Africa in 1911, in Jamaica (then a British colony) in 1913, and in the United Kingdom and New Zealand in the 1920s. Canada criminalized cannabis in the Opium and Drug Act of 1923, before any reports of use of the drug in Canada. In 1925 a compromise was made at an international conference in The Hague about the International Opium Convention that banned exportation of "Indian hemp" to countries that had prohibited its use, and requiring importing countries to issue certificates approving the importation and stating that the shipment was required "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes". It also required parties to "exercise an effective control of such a nature as to prevent the illicit international traffic in Indian hemp and especially in the resin".

In the United States in 1937, the Marihuana Tax Act was passed, and prohibited the production of hemp in addition to cannabis. The reasons that hemp was also included in this law are disputed—several scholars have claimed that the act was passed in order to destroy the US hemp industry, with the primary involvement of businessmen Andrew Mellon, Randolph Hearst, and the Du Pont family. But the improvements of the decorticators, machines that separate the fibers from the hemp stem, could not make hemp fiber a very cheap substitute for fibers from other sources because it could not change that basic fact that strong fibers are only found in the bast, the outer part of the stem. Only about 1/3 of the stem are long and strong fibers. The company DuPont and many industrial historians dispute a link between nylon and hemp. They argue that the purpose of developing the nylon was to produce a fiber that could be used in thin stockings for females and compete with silk.

In New York City, there were more than 19,000 kg (41,000 lb) of marijuana growing like weeds throughout the boroughs until 1951, when the "White Wing Squad", headed by the Sanitation Department General Inspector John E. Gleason, was charged with destroying the many pot farms that had sprouted up across the city. The Brooklyn Public Library reports: this group was held to a high moral standard and was prohibited from "entering saloons, using foul language, and neglecting horses." The Squad found the most weed in Queens but even in Brooklyn dug up "millions of dollars" worth of the plants, many as "tall as Christmas trees". Gleason oversaw incineration of the plants in Woodside, Queens.

The United Nations' 2012 Global Drug Report stated that cannabis "was the world's most widely produced, trafficked, and consumed drug in the world in 2010", identifying that between 119 million and 224 million users existed in the world's adult (18 or older) population.

Society and culture

See also: Cannabis culture| Substance | Best estimate |

Low estimate |

High estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine- type stimulants |

34.16 | 13.42 | 55.24 |

| Cannabis | 192.15 | 165.76 | 234.06 |

| Cocaine | 18.20 | 13.87 | 22.85 |

| Ecstasy | 20.57 | 8.99 | 32.34 |

| Opiates | 19.38 | 13.80 | 26.15 |

| Opioids | 34.26 | 27.01 | 44.54 |

Legal status

Main article: Legality of cannabis See also: Prohibition of drugs and Drug liberalization

Since the beginning of the 20th century, most countries have enacted laws against the cultivation, possession or transfer of cannabis. These laws have impacted adversely on the cannabis plant's cultivation for non-recreational purposes, but there are many regions where, under certain circumstances, handling of cannabis is legal or licensed. Many jurisdictions have lessened the penalties for possession of small quantities of cannabis, so that it is punished by confiscation and sometimes a fine, rather than imprisonment, focusing more on those who traffic the drug on the black market.

In some areas where cannabis use has been historically tolerated, some new restrictions have been put in place, such as the closing of cannabis coffee shops near the borders of the Netherlands, closing of coffee shops near secondary schools in the Netherlands and crackdowns on "Pusher Street" in Christiania, Copenhagen in 2004.

Some jurisdictions use free voluntary treatment programs and/or mandatory treatment programs for frequent known users. Simple possession can carry long prison terms in some countries, particularly in East Asia, where the sale of cannabis may lead to a sentence of life in prison or even execution. More recently however, many political parties, non-profit organizations and causes based on the legalization of medical cannabis and/or legalizing the plant entirely (with some restrictions) have emerged.

In December 2012, the U.S. state of Washington became the first state to officially legalize cannabis in a state law (Washington Initiative 502) (but still illegal by federal law), with the state of Colorado following close behind (Colorado Amendment 64). On January 1, 2013, the first marijuana "club" for private marijuana smoking (no buying or selling, however) was allowed for the first time in Colorado. The California Supreme Court decided in May 2013 that local governments can ban medical marijuana dispensaries despite a state law in California that permits the use of cannabis for medical purposes. At least 180 cities across California have enacted bans in recent years.

In December 2013, Uruguay became the first country to legalize growing, sale and use of cannabis. However, as of August 2014, no cannabis has yet been sold legally in Uruguay. According to the law, the only cannabis that can be sold legally must be grown in the country by no more than five licensed growers, and these have yet to be selected; in fact the call for applications did not go out until August 1, 2014. In the elections of October 2014, there is a significant chance that lawmakers opposed to legal cannabis will come to control the legislature, and the law will be repealed before it has fully taken effect.

On October 17, 2015, Australian health minister Sussan Ley presented a new law that will allow the cultivation of cannabis for scientific research and medical trails on patients. In December 2015, it was reported that the Canadian government had committed to legalizing cannabis, but at that time no timeline for the legalization was set out.

Usage

In 2013, between 128 and 232 million people used cannabis (2.7% to 4.9% of the global population between the ages of 15 and 65).

United States

In 2015, almost half of the people in the United States have tried marijuana, 12% have used it in the past year, and 7.3% have used it in the past month. Daily marijuana use amongst US college students has reached its highest level on record rising from 3.5% in 2007 to 5.9% in 2014 and has surpassed daily cigarette use.

In the US, men are over twice as likely to use marijuana as women and 18-29 year-olds are six times more likely to use as over 65-year-olds. In 2015, a record 44% of the US population has tried marijuana in their lifetime, an increase from 38% in 2013 and 33% in 1985.

Economics

Production

Main article: Cannabis cultivationIt is often claimed by growers and breeders of herbal cannabis that advances in breeding and cultivation techniques have increased the potency of cannabis since the late 1960s and early '70s, when THC was first discovered and understood. However, potent seedless cannabis such as "Thai sticks" were already available at that time. Sinsemilla (Spanish for "without seed") is the dried, seedless inflorescences of female cannabis plants. Because THC production drops off once pollination occurs, the male plants (which produce little THC themselves) are eliminated before they shed pollen to prevent pollination. Advanced cultivation techniques such as hydroponics, cloning, high-intensity artificial lighting, and the sea of green method are frequently employed as a response (in part) to prohibition enforcement efforts that make outdoor cultivation more risky. It is often cited that the average levels of THC in cannabis sold in United States rose dramatically between the 1970s and 2000, but such statements are likely skewed because of undue weight given to much more expensive and potent, but less prevalent samples.

"Skunk" refers to several named strains of potent cannabis, grown through selective breeding and sometimes hydroponics. It is a cross-breed of Cannabis sativa and C. indica (although other strains of this mix exist in abundance). Skunk cannabis potency ranges usually from 6% to 15% and rarely as high as 20%. The average THC level in coffee shops in the Netherlands is about 18–19%.

Price

The price or street value of cannabis varies widely depending on geographic area and potency.

In the United States, cannabis is overall the number four value crop, and is number one or two in many states including California, New York and Florida, averaging $3,000/lb. It is believed to generate an estimated $36 billion market. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical U.S. retail prices are $10–15 per gram (approximately $280–420 per ounce). Street prices in North America are known to range from about $40 to $400 per ounce, depending on quality.

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that typical retail prices in Europe for cannabis varies from €2 to €20 per gram, with a majority of European countries reporting prices in the range €4–10.

Distribution

Marijuana vending machines for selling or dispensing cannabis are in use in the United States and are planned to be used in Canada.

Gateway drug

Main article: Gateway drug theoryThe Gateway Hypothesis states that cannabis use increases the probability of trying "harder" drugs. The hypothesis has been hotly debated as it is regarded by some as the primary rationale for the United States prohibition on cannabis use. A Pew Research Center poll found that political opposition to marijuana use was significantly associated with concerns about health effects and whether legalization would increase marijuana use by children.

Some studies state that while there is no proof for the gateway hypothesis, young cannabis users should still be considered as a risk group for intervention programs. Other findings indicate that hard drug users are likely to be poly-drug users, and that interventions must address the use of multiple drugs instead of a single hard drug. Almost two-thirds of the poly drug users in the "2009/10 Scottish Crime and Justice Survey" used cannabis.

The gateway effect may appear due to social factors involved in using any illegal drug. Because of the illegal status of cannabis, its consumers are likely to find themselves in situations allowing them to acquaint with individuals using or selling other illegal drugs. Utilizing this argument some studies have shown that alcohol and tobacco may additionally be regarded as gateway drugs; however, a more parsimonious explanation could be that cannabis is simply more readily available (and at an earlier age) than illegal hard drugs. In turn alcohol and tobacco are easier to obtain at an earlier point than is cannabis (though the reverse may be true in some areas), thus leading to the "gateway sequence" in those individuals since they are most likely to experiment with any drug offered.

An alternative to the gateway hypothesis is the common liability to addiction (CLA) theory. It states that some individuals are, for various reasons, willing to try multiple recreational substances. The "gateway" drugs are merely those that are (usually) available at an earlier age than the harder drugs. Researchers have noted in an extensive review, Vanyukov et al., that it is dangerous to present the sequence of events described in gateway "theory" in causative terms as this hinders both research and intervention.

Research

Further information: Medical cannabis#ResearchCannabis research is challenging since the plant is illegal in most countries. Research-grade samples of the drug are difficult to obtain for research purposes, unless granted under authority of national governments.

There are also other difficulties in researching the effects of cannabis. Many people who smoke cannabis also smoke tobacco. This causes confounding factors, where questions arise as to whether the tobacco, the cannabis, or both that have caused a cancer. Another difficulty researchers have is in recruiting people who smoke cannabis into studies. Because cannabis is an illegal drug in many countries, people may be reluctant to take part in research, and if they do agree to take part, they may not say how much cannabis they actually smoke.

Footnotes

a: Weed, pot, grass, and herb are among the many other nicknames for cannabis as a drug.

b: Sources for this section and more information can be found in the Medical cannabis article

See also

References

- Mahmoud A. ElSohly (2007). Marijuana and the Cannabinoids. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-59259-947-9.

- ^ United Nations. "World Drug Report 2013" (PDF). The united Nations. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- "Medical Use of Marijuana". Health Canada. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "New Colombia Resources Inc Subsidiary, Sannabis, Produces First Batch of Medical Marijuana Based Products in Colombia to Fill Back Orders". prnewswire.com. PR Newswire. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Rana Moussaoui (Nov 25, 2013). "Lebanon cannabis trade thrives in shadow of Syrian war". AFP.

- ^ Sanie Lopez Garelli (25 November 2008). "Mexico, Paraguay top pot producers, U.N. report says". CNN International. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- Vij (2012). Textbook Of Forensic Medicine And Toxicology: Principles And Practice. Elsevier India. p. 672. ISBN 978-81-312-1129-8.See also article on Marijuana as a word.

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries (2007). Spanish Word Histories and Mysteries: English Words That Come From Spanish. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-547-35021-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Ethan B Russo (2013). Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-136-61493-4.

- Newton, David E. (2013). Marijuana : a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 7. ISBN 9781610691499.

- ^ "DrugFacts: Marijuana". National Institute on Drug Abuse. March 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Marijuana: Factsheets: Appetite". Adai.uw.edu. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- "Marijuana intoxication: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- Crippa, JA; Zuardi, AW; Martín-Santos, R; Bhattacharyya, S; Atakan, Z; McGuire, P; Fusar-Poli, P (October 2009). "Cannabis and anxiety: a critical review of the evidence". Human psychopharmacology. 24 (7): 515–23. doi:10.1002/hup.1048. PMID 19693792.

- ^ Riviello, Ralph J. (2010). Manual of forensic emergency medicine : a guide for clinicians. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 9780763744625.

- ^ "Status and Trend Analysis of Illict [sic] Drug Markets". World Drug Report 2015 (pdf). p. 23. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- http://www.cbsnews.com/news/marijuana-use-and-support-for-legal-marijuana-continue-to-climb/

- ^ Motel, Seth (14 April 2015). "6 facts about marijuana". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Martin Booth (2003). Cannabis: A History. Transworld. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4090-8489-1.

- "Cannabis: Legal Status". Erowid.org. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- UNODC. World Drug Report 2010. United Nations Publication. p. 198. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- "23 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC Laws, Fees, and Possession Limits". ProCon. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ Gallup, Inc. "More Than Four in 10 Americans Say They Have Tried Marijuana". Gallup.com.

- Linshi, Jack (2014-06-26). "Americans Are Smoking More Pot". Time.

- ^ Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS (February 2013). "The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis". Pharmacotherapy (Review). 33 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1002/phar.1187. PMID 23386598.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Whiting, PF; Wolff, RF; Deshpande, S; Di Nisio, M; Duffy, S; Hernandez, AV; Keurentjes, JC; Lang, S; Misso, K; Ryder, S; Schmidlkofer, S; Westwood, M; Kleijnen, J (23 June 2015). "Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 313 (24): 2456–2473. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6358. PMID 26103030.

- ^ Wang T, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Ware MA (June 2008). "Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: a systematic review". CMAJ (Review). 178 (13): 1669–78. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071178. PMC 2413308. PMID 18559804.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jordan K, Sippel C, Schmoll HJ (September 2007). "Guidelines for antiemetic treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future recommendations". Oncologist (Review). 12 (9): 1143–50. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1143. PMID 17914084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "State-Level Proposals to Legalize Marijuana". asam.org.

- "The Myth of Medical". Scholastic Inc. 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Emmanuel S Onaivi; Takayuki Sugiura; Vincenzo Di Marzo (2005). Endocannabinoids: The Brain and Body's Marijuana and Beyond. Taylor & Francis. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-415-30008-7.

- http://cannabislink.ca/info/MotivationsforCannabisUsebyCanadianAdults-2008.pdf

- "Medication-Associated Depersonalization Symptoms"Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Shufman, E; Lerner, A; Witztum, E (2005). "Depersonalization after withdrawal from cannabis usage" (PDF). Harefuah (in Hebrew). 144 (4): 249–51, 303. PMID 15889607. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2005.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Johnson, BA (1990). "Psychopharmacological effects of cannabis". British journal of hospital medicine. 43 (2): 114–6, 118–20, 122. PMID 2178712.

- Wayne Hall; Rosalie Liccardo Pacula (2003). Cannabis Use and Dependence: Public Health and Public Policy. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-521-80024-2.

- Mathre, Mary Lynn, ed. (1997). Cannabis in Medical Practice: A Legal, Historical, and Pharmacological Overview of the Therapeutic Use of Marijuana. University of Virginia Medical Center. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-7864-8390-7.

- Riedel, G.; Davies, S.N. (2005). "Cannabinoid function in learning, memory and plasticity". Handb Exp Pharmacol. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 168 (168): 446. doi:10.1007/3-540-26573-2_15. ISBN 3-540-22565-X. PMID 16596784.

- Barceloux, Donald G (20 March 2012). "Chapter 60: Marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) and synthetic cannabinoids". Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. John Wiley & Sons. p. 915. ISBN 978-0-471-72760-6.

- "Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology – Jurema-Preta (Mimosa tenuiflora [Willd.] Poir.): a review of its traditional use, phytochemistry and pharmacology". scielo.br. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- Bloomquist, Edward (1971). Marijuana: The Second Trip. California: Glencoe.

- Courtwright, David (2001). Forces of Habit: Drugs and the Making of the Modern World. Harvard Univ. Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-674-00458-2.

- Andrew Golub (2012). The Cultural/Subcultural Contexts of Marijuana Use at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-136-44627-6.

- Allan Tasman; Jerald Kay; Jeffrey A. Lieberman; Michael B. First; Mario Maj (2011). Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-119-96540-4.

- Ed Rosenthal (2002). Ask Ed: Marijuana Gold: Trash to Stash. Perseus Books Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-936807-02-4.

- "Cannabis and Cannabis Extracts: Greater Than the Sum of Their Parts?" (PDF). Cannabis-med.org. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- Template:ChemID

- Dale Gieringer, Ph.D.; Ed Rosenthal (2008). Marijuana medical handbook: practical guide to therapeutic uses of marijuana. QUICK AMER Publishing Company. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-932551-86-3.

- Taylor, M.; Mackay, K.; Murphy, J.; McIntosh, A.; McIntosh, C.; Anderson, S.; Welch, K. (24 July 2012). "Quantifying the RR of harm to self and others from substance misuse: results from a survey of clinical experts across Scotland". BMJ Open. 2 (4): e000774 – e000774. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000774. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011. National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2011. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- "www.samhsa.gov".

- ^ Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR (2014). "Adverse health effects of marijuana use". N. Engl. J. Med. 370 (23): 2219–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1402309. PMID 24897085.

- Gordon AJ, Conley JW, Gordon JM (December 2013). "Medical consequences of marijuana use: a review of current literature". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 15 (12): 419. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0419-7. PMID 24234874.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Committee on Obstetric Practice (July 2015). "Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 126 (1): 234–238. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000467192.89321.a6.

- Gunn, J K L; Rosales, C B; Center, K E; Nuñez, A; Gibson, S J; Christ, C; Ehiri, J E (5 April 2016). "Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 6 (4): e009986. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009986.

- Subbaraman, M. S. (8 January 2014). "Can Cannabis be Considered a Substitute Medication for Alcohol?". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 49 (3): 292–298. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agt182. PMID 24402247.

- Lachenmeier, Dirk W.; Rehm, Jürgen (30 January 2015). "Comparative risk assessment of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis and other illicit drugs using the margin of exposure approach". Scientific Reports. 5: 8126. doi:10.1038/srep08126.

- ^ W. Hall, N. Solowij (1998-11-14). "Adverse effects of cannabis". Lancet. 352 (9140): 1611–16. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05021-1. PMID 9843121.

- Oltmanns, Thomas; Emery, Robert (2015). Abnormal Psychology. New Jersey: Pearson. p. 294. ISBN 0205970745.

- "Sativex Oral Mucosal Spray Public Assessment Report. Decentralized Procedure" (PDF). United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. p. 93. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

There is clear evidence that recreational cannabis can produce a transient toxic psychosis in larger doses or in susceptible individuals, which is said to characteristically resolve within a week or so of absence (Johns 2001). Transient psychotic episodes as a component of acute intoxication are well-documented (Hall et al 1994)

- D'Souza, DC; Sewell, RA; Ranganathan, M (October 2009). "Cannabis and psychosis/schizophrenia: human studies". European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 259 (7): 413–31. doi:10.1007/s00406-009-0024-2. PMC 2864503. PMID 19609589.

- ^ Calabria B; et al. (May 2010). "Does cannabis use increase the risk of death? Systematic review of epidemiological evidence on adverse effects of cannabis use". Drug Alcohol Rev. 29 (3): 318–30. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00149.x. PMID 20565525.

- Lubman, DI; Cheetham, A; Yücel, M (April 2015). "Cannabis and adolescent brain development". Pharmacology & therapeutics. 148: 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.009. PMID 25460036.

- Stephen Maisto; Mark Galizio; Gerard Connors (2014). Drug Use and Abuse. Cengage Learning. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-305-17759-8.

- ^ Tashkin, DP (June 2013). "Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 10 (3): 239–47. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201212-127fr. PMID 23802821.

- Tetrault, JM; Crothers, K; Moore, BA; Mehra, R; Concato, J; Fiellin, DA (12 February 2007). "Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review". Archives of Internal Medicine. 167 (3): 221–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.3.221. PMID 17296876.

- Hashibe, M; Straif, K; Tashkin, DP; Morgenstern, H; Greenland, S; Zhang, ZF (April 2005). "Epidemiologic review of marijuana use and cancer risk". Alcohol (Fayetteville, N.Y.). 35 (3): 265–75. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.008. PMID 16054989.

- "Does smoking cannabis cause cancer?". Cancer Research UK. 2010-09-20. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Tashkin, Donald (March 1997). "Effects of marijuana on the lung and its immune defenses". UCLA School of Medicine. Retrieved 2012-06-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Gates, P; Jaffe, A; Copeland, J (July 2014). "Cannabis smoking and respiratory health: consideration of the literature". Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 19 (5): 655–62. doi:10.1111/resp.12298. PMID 24831571.

- Huang, YH; Zhang, ZF; Tashkin, DP; Feng, B; Straif, K; Hashibe, M (January 2015). "An epidemiologic review of marijuana and cancer: an update". Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 24 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1026. PMID 25587109.

- Gurney, J; Shaw, C; Stanley, J; Signal, V; Sarfati, D (11 November 2015). "Cannabis exposure and risk of testicular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cancer. 15 (1): 897. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1905-6. PMID 26560314.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - A. Riecher-Rössler (2014). Comorbidity of Mental and Physical Disorders. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 978-3-318-02604-7.

- Cottencin O. (Dec 2010). "Cannabis arteritis: review of the literature". J Addict Med (Review). 4 (4): 191–6. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181beb022. PMID 21769037.

- Thomas G (2014-01-01). "Adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular effects of marijuana inhalation: what cardiologists need to know". Am J Cardiol. 113 (1): 187–90. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.042. PMID 24176069.

- RT Jones (2002). "Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana". J Clin Pharmacol (Review). 42 (11 Suppl): 58S – 63S. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06004.x. PMID 12412837.

- ^ Hall, W (January 2015). "What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use?". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 110 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1111/add.12703. PMID 25287883.

- Franz, CA; Frishman, WH (9 February 2016). "Marijuana Use and Cardiovascular Disease". Cardiology in review. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000103. PMID 26886465.

- ^ Batalla, Albert; et al. (2013). "Structural and Functional Imaging Studies in Chronic Cannabis Users: A Systematic Review of Adolescent and Adult Findings". PLoS ONE. 8 (2): e55821. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055821. PMID 23390554.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Martín-Santos, R; et al. (2010). "Neuroimaging in cannabis use: a systematic review of the literature". Psychological Medicine. 40 (3): 383–98. doi:10.1017/S0033291709990729. PMID 19627647.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Crean, RD; Crane, NA; Mason, BJ (March 2011). "An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions". Journal of addiction medicine. 5 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e31820c23fa. PMC 3037578. PMID 21321675.

- Rocchetti, M; Crescini, A; Borgwardt, S; Caverzasi, E; Politi, P; Atakan, Z; Fusar-Poli, P (November 2013). "Is cannabis neurotoxic for the healthy brain? A meta-analytical review of structural brain alterations in non-psychotic users". Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 67 (7): 483–92. doi:10.1111/pcn.12085. PMID 24118193.

- Schreiner, AM; Dunn, ME (October 2012). "Residual effects of cannabis use on neurocognitive performance after prolonged abstinence: a meta-analysis". Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 20 (5): 420–9. doi:10.1037/a0029117. PMID 22731735.

- Lorenzetti, V; Solowij, N; Yücel, M (4 December 2015). "The Role of Cannabinoids in Neuroanatomic Alterations in Cannabis Users". Biological Psychiatry. 79: e17–31. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.11.013. PMID 26858212.

- Colizzi, M; McGuir, P; Pertwee, RG; Bhattacharyya, S (14 March 2016). "EFFECT OF CANNABIS ON GLUTAMATE SIGNALLING IN THE BRAIN: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL EVIDENCE". Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 64: 359–81. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.010. PMID 26987641.

- Borges, G; Bagge, CL; Orozco, R (9 February 2016). "A literature review and meta-analyses of cannabis use and suicidality". Journal of Affective Disorders. 195: 63–74. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.007. PMID 26872332.

- van Holst, RJ; Schilt, T (March 2011). "Drug-related decrease in neuropsychological functions of abstinent drug users". Current drug abuse reviews. 4 (1): 42–56. doi:10.2174/1874473711104010042. PMID 21466500.

- "Withdrawal Symptoms From Smoking Pot?". WebMD.

- Hall, W; Degenhardt, L (17 October 2009). "Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use". Lancet. 374 (9698): 1383–91. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61037-0. PMID 19837255.

- Subbaraman, MS (2014). "Can cannabis be considered a substitute medication for alcohol?". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 49 (3): 292–8. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agt182. PMID 24402247.

- Li, M.-C.; Brady, J. E.; DiMaggio, C. J.; Lusardi, A. R.; Tzong, K. Y.; Li, G. (4 October 2011). "Marijuana Use and Motor Vehicle Crashes". Epidemiologic Reviews. 34 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxr017. PMC 3276316. PMID 21976636.

- Rogeberg, O; Elvik, R (16 February 2016). "The effects of cannabis intoxication on motor vehicle collision revisited and revised". Addiction (Abingdon, England). doi:10.1111/add.13347. PMID 26878835.

- ^ Wayne Hall; Rosalie Liccardo Pacula (2003). Cannabis Use and Dependence: Public Health and Public Policy. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-521-80024-2.

- Leo E. Hollister; et al. (March 1986). "Health aspects of cannabis". Pharma Review (38): 1–20. Archived from the original on 1986. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - Juan Iovanna; Uktam Ismailov (2009). Pancreatology: From Bench to Bedside. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 978-3-642-00152-9.

- Wilson, R. & Nicoll, A. (2002). "Endocannabinoid signaling in the brain". Science. 296 (5568): 678–682. doi:10.1126/science.1063545. PMID 11976437.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fernandez, J. & Allison, B. (2004). "Rimbonabant Sanofi-Synthelabo". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs (5): 430–435.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Atta-ur- Rahman; Allen B. Reitz (2005). Frontiers in Medicinal Chemistry. Bentham Science Publishers. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-60805-205-9.

- Kathmann, Markus; Flau, Karsten; Redmer, Agnes; Tränkle, Christian; Schlicker, Eberhard (2006). "Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at mu- and delta-opioid receptors". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 372 (5): 354–361. doi:10.1007/s00210-006-0033-x. PMID 16489449.

- Nadia Hejazi, Chunyi Zhou, Murat Oz, Hui Sun, Jiang Hong Ye, Li Zhang (March 2006). "Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and endogenous cannabinoid anandamide directly potentiate the function of glycine peceptors" (PDF). Molecular Pharmacology. 69 (3): 991–7. doi:10.1124/mol.105.019174. PMID 16332990.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Donald G. Barceloux (3 February 2012). Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 910–. ISBN 978-1-118-10605-1. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Randall Clint Baselt (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Biomedical Publications. pp. 1513–1518. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- Leslie M. Shaw; Tai C. Kwong (2001). The Clinical Toxicology Laboratory: Contemporary Practice of Poisoning Evaluation. Amer. Assoc. for Clinical Chemistry. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-890883-53-9.

- John Kelly (2010-06-28). "Has the most common marijuana test resulted in tens of thousands of wrongful convictions?". AlterNet.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Venkatratnam, Abhishek; Nathan H. Lents (July 2011). "Zinc Reduces the Detection of Cocaine, Methamphetamine, and THC by ELISA Urine Testing". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 35 (6): 333–340. doi:10.1093/anatox/35.6.333. PMID 21740689.

- Lin, Chia-Ni; Strathmann, Frederick (July 10, 2013). "Elevated Urine Zinc Concentration Reduces the Detection of Methamphetamine, Cocaine, THC and Opiates in Urine by EMIT" (PDF). Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 37: 665–669. doi:10.1093/jat/bkt056.

- ^ J. E. Joy, S. J. Watson, Jr., and J. A. Benson, Jr. (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing The Science Base. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 0-585-05800-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Why Does Cannabis Potency Matter?". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2009-06-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Cascini, F; Aiello, C; Di Tanna, G (March 2012). "Increasing delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ-9-THC) content in herbal cannabis over time: systematic review and meta-analysis". Current drug abuse reviews. 5 (1): 32–40. doi:10.2174/1874473711205010032. PMID 22150622.

- Dana Smith. "Cannabis and memory loss: dude, where's my CBD?". the Guardian.

- "Cannabis Potency". National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "BBC: Cannabis laws to be strengthened. May 2008 20:55 UK". BBC News. 2008-05-07. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- Di Forti, M; Morgan, C; Dazzan, P; Pariante, C; Mondelli, V; Marques, TR; Handley, R; Luzi, S; Russo, M (2009). "High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis". British Journal of Psychiatry. 195 (6): 488–91. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.064220. PMC 2801827. PMID 19949195.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - Hope, Christopher (2008-02-06). "Use of extra strong 'skunk' cannabis soars". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- Harold Doweiko (2011). Concepts of Chemical Dependency. Cengage Learning. p. 124. ISBN 1-133-17081-1.

- Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries (2007). Spanish Word Histories and Mysteries: English Words That Come From Spanish. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 142. ISBN 0-547-35021-X.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Dr Gary Potter; Mr Martin Bouchard; Mr Tom Decorte (2013). World Wide Weed: Global Trends in Cannabis Cultivation and its Control (revised ed.). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4094-9438-6.

- Wayne Hall; Rosalie Liccardo Pacula (2003). Cannabis Use and Dependence: Public Health and Public Policy. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-80024-2.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2009). Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Cannabis and Cannabis Products. United Nations Publications. p. 15. ISBN 978-92-1-148242-3.

- ^ Max M. Houck (2015). Forensic Chemistry. Elsevier Science. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-12-800624-5.

- Patricia A. Adler; Peter Adler; Patrick K. O'Brien (February 28, 2012). Drugs and the American Dream: An Anthology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 330–. ISBN 978-0-470-67027-9.

- Clayton J. Mosher; Scott M. Akins (August 20, 2013). Drugs and Drug Policy: The Control of Consciousness Alteration. SAGE Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4833-2188-2.

- "Hemp Facts". Naihc.org. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

- "Decarboxylation – Does Marijuana Have to be Heated to Become Psychoactive?". Cannabisculture.com. 2003-01-02. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- Ed Rosenthal (2002). Ask Ed : Marijuana Gold: Trash to Stash. QUICK AMER Publishing Company. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-932551-52-8.

- "Kief". Cannabisculture.com. 2005-03-09. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- David Bukszpan (2012). Is That a Word?: From AA to ZZZ, the Weird and Wonderful Language of SCRABBLE. Chronicle Books. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4521-0824-7.

- "Hashish". dictionary.reference.com.

- Castle/Murray/D'Souza (2004). Marijuana and Madness. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-139-50267-2.

- Raymond Goldberg (2012). Drugs Across the Spectrum, 7th ed. Cengage Learning. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-133-59416-1.

- Alchimia Blog, Rosin Hash

- Leslie L. Iversen (2000). The Science of Marijuana. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-515110-7.

- Jeffrey A. Cohen; Richard A. Rudick (2011). Multiple Sclerosis Therapeutics. Cambridge University Press. p. 670. ISBN 978-1-139-50237-5.

- Leslie A. King (2009). Forensic Chemistry of Substance Misuse: A Guide to Drug Control. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-85404-178-7.

- "Dabs—marijuana's explosive secret". Cnbc.com. 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- World Drug Report. United Nations Publications. 2009. p. 98.

- Alison Hallett for Wired. Feb. 20, 2013 Hash Oil is Blowing Up Across the U.S. –Literally

- Pascal Kintz (2014). Toxicological Aspects of Drug-Facilitated Crimes. Elsevier Science. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-12-416969-2.

- Elise McDonough; Editors of High Times Magazine (2012). The Official High Times Cannabis Cookbook: More Than 50 Irresistible Recipes That Will Get You High. Chronicle Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4521-0133-0.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - Leslie L. Iversen Professor of Pharmacology University of Oxford (2007). The Science of Marijuana. Oxford University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-19-979598-7.

- Flin Flon Mine Area Marijuana Contamination, Medicalmarihuana.ca, archived from the original on April 25, 2009, retrieved 2011-04-20

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Warnings over glass in cannabis". BBC News. 2007-02-01. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "Electronenmicroscopisch onderzoek van vervuilde wietmonsters" (PDF).

- Busse F, Omidi L, Timper K; et al. (April 2008). "Lead poisoning due to adulterated marijuana". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (15): 1641–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0707784. PMID 18403778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hall, W.; Nelson, J. (1995). Public perceptions of the health and psychological consequences of cannabis use. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 978-0-644-42830-9.

- StollzNow (2006). Market research report: Australians on cannabis. Report prepared for NDARC and Pfizer Australia. Sydney: StollzNow Research and Advisory.

- "PCP Laced Marijuana: Creating Psychosis and Psychiatric Commitment". Citizens Commission on Human Rights, CCHR.

- Michael Backes (2014). Cannabis Pharmacy: The Practical Guide to Medical Marijuana. Hachette Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-60376-334-9.

- Alison Matthews; Laurence Matthews (2007). Tuttle Learning Chinese Characters: A Revolutionary New Way to Learn and Remember the 800 Most Basic Chinese Characters. Tuttle Publishing. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-8048-3816-0.

- Peter G. Stafford; Jeremy Bigwood (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Ronin Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-914171-51-5.

- "Marijuana and the Cannabinoids", ElSohly (p. 8).

- Rudgley, Richard (1998). Lost Civilisations of the Stone Age. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-85580-1.

- "Lab work to identify 2,800-year-old mummy of shaman". People's Daily Online. 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hong-En Jiang; et al. (2006). "A new insight into Cannabis sativa (Cannabaceae) utilization from 2500-year-old Yanghai tombs, Xinjiang, China". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 108 (3): 414–22. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.034. PMID 16879937.

- Parsche, Franz; Nerlich, Andreas (1995). "Presence of drugs in different tissues of an egyptian mummy". Fresenius' Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 352 (3–4): 380–384. doi:10.1007/BF00322236.

- Balabanova, S.; Parsche, S.; Pirsig, W. (August 1992). "First identification of drugs in Egyptian mummies". Naturwissenschaften. 79 (8): 358–358. doi:10.1007/BF01140178.

- Leary, Timothy (1990). Tarcher & Putnam (ed.). Flashbacks. New York: GP Putnam's Sons. ISBN 0-87477-870-0.

- Miller, Ga (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 34 (11 ed.). pp. 761–2. doi:10.1126/science.34.883.761. PMID 17759460. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Rudgley, Richard (1998). Little, Brown; et al. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances. ISBN 0-349-11127-8.

- Franck, Mel (1997). Marijuana Grower's Guide. Red Eye Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-929349-03-2.

- Rubin, Vera D (1976). Cannabis and Culture. Campus Verlag. p. 305. ISBN 3-593-37442-0.

- Cunliffe, Barry W (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 0-19-285441-0.

- Walton, Robert P (1938). Marijuana, America's New Drug Problem. JB Lippincott. p. 6.

- Ibn Taymiyya (2001). Le haschich et l'extase (in French). Beyrouth: Albouraq. ISBN 2-84161-174-4.

- "Bard 'used drugs for inspiration'". BBC News. 2001-03-01. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- "Drugs clue to Shakespeare's genius". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. 2001-03-01. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- John G. Bourke (1984-01-05). "Popular medicine, customs, and superstitions of the Rio Grande". Journal of American folklore. 7–8: 138.

- "(Record of "marijuan" sample submitted by Bourke to the National Museum, 1892)".

- Bourke cites an anonymous writer in the "Evening Star", Washington, D. C., January 13, 1894 for additional remarks on the use of mariguan and Jamestown weed by inhabitants of the area.

- "Statement of Dr. William C. Woodward". Drug library. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Debunking the Hemp Conspiracy Theory".

- W. W. Willoughby (1925). "Opium as an international problem". Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Opium as an international problem: the Geneva conferences – Westel Woodbury Willoughby at Google Books

- ^ Laurence Armand French; Magdaleno Manzanárez (2004). Nafta & Neocolonialism: Comparative Criminal, Human & Social Justice. University Press of America. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7618-2890-7.

- Mitch Earleywine (2002). Understanding Marijuana: A New Look at the Scientific Evidence. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-513893-1.

- ^ Preston Peet (2004). Under The Influence: The Disinformation Guide To Drugs. Consortium. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-932857-00-9.

- Hayo M.G. van der Werf : Hemp facts and hemp fiction. Archived 2013-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Dr. Ivan BÛcsa, GATE Agricultural Research Institute, Kompolt – Hungary, Book Review Re-discovery of the Crop Plant Cannabis Marihuana Hemp (Die Wiederentdeckung der Nutzplanze Cannabis Marihuana Hanf) Archived 2012-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Sterling Evans (2007). Bound in twine: the history and ecology of the henequen-wheat complex for Mexico and the American and Canadian Plains, 1880–1950. Texas A&M University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-58544-596-7.

- "the history of nylon". caimateriali.org.

- "Nylon: A Revolution in Textiles". chemheritage.org.

- American Chemical Society: THE FIRST NYLON PLANT. 1995

- Van Luling, Todd (2014-04-17). "8 Things Even New Yorkers Don't Know About New York City". The Huffington Post.

- Eliana Dockterman (29 June 2012). "Marijuana Now the Most Popular Drug in the World". Time NewsFeed. Time Inc. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- "Annual prevalence of use of drugs, by region and globally, 2016". World Drug Report 2018. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- David Levinson (2002). Encyclopedia of Crime and Punishment. SAGE Publications. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-7619-2258-2.

- "Many Dutch coffee shops close as liberal policies change, Exaptica". Expatica.com. 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- EMCDDA Cannabis reader: Global issues and local experiences, Perspectives on Cannabis controversies, treatment and regulation in Europe, 2008, p. 157.

- "43 Amsterdam coffee shops to close door", Radio Netherlands, Friday 21 November 2008 Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Marijuana goes legal in Washington state amid mixed messages". Reuters. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Alan Duke (2012-11-08). "2 states legalize pot, but don't 'break out the Cheetos' yet". CNN.com. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- "Marijuana clubs ring in new year in Colorado as legalized pot smoking begins". Abcnews.go.com. 2013-01-01. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Horward Mintz (2013-05-06). "Medical pot: California Supreme Court allows cities to ban weed dispensaries". Marin Independent Journal. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Vicky Baker. "Marijuana laws around the world: what you need to know". the Guardian.

- "Lanzan llamado a interesados en producir y distribuir marihuana", "El País" , August 1, 2014, http://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/llamado-interesados-producir-distribuir-marihuana.html

- "Marihuana: con mayoría en contra, la ley avanza lento", "El País" , July 24, 2014, http://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/marihuana-mayoria-contra-ley-avanza.html

- Leonardo Haberkorn (correspondent for the Associated Press in Uruguay), "Uruguay's budding plan for legal pot faces hurdles", "Houston Chronicle", August 1, 2014, http://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/nation-world/world/article/Uruguay-s-budding-plan-for-legal-pot-faces-hurdles-5663817.php

- "Uruguay's Marijuana Marketplace Program Could Be Going Up In Smoke", Fox News Latino, August 3, 2014, http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/money/2014/08/03/uruguay-marijuana-marketplace-program-could-be-going-up-in-smoke/

- Alchimia Blog, Medical marijuana news, December 2015

- "Canadians facing pot charges in limbo, while Liberals work on legalization". The Globe and Mail.