| Revision as of 01:55, 25 October 2014 editEinsteiniated (talk | contribs)4 edits →Other uses← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:07, 9 December 2024 edit undoTTWIDEE (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,913 edits Added redirect hatnote | ||

| (484 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Chemical compound}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|text=the ] ion or ]}} | |||

| {{Redirect|E926|the furry-themed website e926|e621 (website)}} | |||

| {{Chembox | {{Chembox | ||

| | Watchedfields = changed | |||

| | verifiedrevid = 476998061 | | verifiedrevid = 476998061 | ||

| | ImageFileL1 = Chlorine-dioxide.png | | ImageFileL1 = Chlorine-dioxide.png | ||

| | |

| ImageFileL1_Ref = {{Chemboximage|correct|??}} | ||

| | |

| ImageNameL1 = Structural formula of chlorine dioxide with assorted dimensions | ||

| | ImageFileR1 = Chlorine-dioxide-3D-vdW. |

| ImageFileR1 = Chlorine-dioxide-3D-vdW.svg | ||

| | |

| ImageFileR1_Ref = {{Chemboximage|correct|??}} | ||

| | |

| ImageNameR1 = Spacefill model of chlorine dioxide | ||

| | |

| ImageFile2 = Chlorine dioxide gas and solution.jpg | ||

| | |

| ImageSize2 = 160 | ||

| | IUPACName = Chlorine dioxide | | IUPACName = Chlorine dioxide | ||

| | SystematicName = <!-- Dioxo-λ<sup>4</sup>-chlorane (substitutive) OR Dioxidochlorine(•) (additive) --> | | SystematicName = <!-- Dioxo-λ<sup>4</sup>-chlorane (substitutive) OR Dioxidochlorine(•) (additive) --> | ||

| | OtherNames = Chlorine(IV) oxide |

| OtherNames = {{Unbulleted list|Chlorine(IV) oxide}} | ||

| |Section1={{Chembox Identifiers | |||

| Chloryl | |||

| | CASNo = 10049-04-4 | |||

| | Section1 = {{Chembox Identifiers | |||

| | CASNo_Ref = {{cascite|correct|CAS}} | |||

| | CASNo = 10049-04-4 | |||

| | PubChem = 24870 | |||

| | CASNo_Ref = {{cascite|correct|CAS}} | |||

| | |

| ChemSpiderID = 23251 | ||

| | |

| ChemSpiderID_Ref = {{chemspidercite|correct|chemspider}} | ||

| | UNII_Ref = {{fdacite|correct|FDA}} | |||

| | ChemSpiderID = 23251 | |||

| | UNII = 8061YMS4RM | |||

| | ChemSpiderID_Ref = {{chemspidercite|correct|chemspider}} | |||

| | |

| UNNumber = 9191 | ||

| | EINECS = 233-162-8 | |||

| | UNII_Ref = {{fdacite|correct|FDA}} | |||

| | MeSHName = Chlorine+dioxide | |||

| | EINECS = 233-162-8 | |||

| | ChEBI_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} | |||

| | MeSHName = Chlorine+dioxide | |||

| | ChEBI_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} | |||

| | ChEBI = 29415 | | ChEBI = 29415 | ||

| | |

| RTECS = FO3000000 | ||

| | |

| Gmelin = 1265 | ||

| | |

| SMILES = O==O | ||

| | |

| SMILES1 = O=Cl | ||

| | |

| StdInChI = 1S/ClO2/c2-1-3 | ||

| | |

| StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} | ||

| | |

| InChI = 1/ClO2/c2-1-3 | ||

| | |

| StdInChIKey = OSVXSBDYLRYLIG-UHFFFAOYSA-N | ||

| | |

| StdInChIKey_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} | ||

| | |

| InChIKey = OSVXSBDYLRYLIG-UHFFFAOYAC}} | ||

| | |

|Section2={{Chembox Properties | ||

| | |

| Cl=1 | O=2 | ||

| | Appearance = Yellow to reddish gas | |||

| | O = 2 | |||

| | Odor = Acrid | |||

| | ExactMass = 66.958681951 g mol<sup>−1</sup> | |||

| | Density = 2.757 g dm<sup>−3</sup><ref>{{CRC91|page=4–58}}</ref> | |||

| | Appearance = Yellow to reddish gas | |||

| | |

| MeltingPtC = -59 | ||

| | BoilingPtC = 11 | |||

| | Density = 2.757 g dm<sup>−3</sup><ref>{{CRC91|page=4–58}}</ref> | |||

| | Solubility = 8 g/L at 20 °C | |||

| | MeltingPtC = -59 | |||

| | SolubleOther = Soluble in alkaline solutions and ] | |||

| | BoilingPtC = 11 | |||

| | |

| HenryConstant = {{val|4.01e-2|u=atm m<sup>3</sup> mol<sup>−1</sup>}} | ||

| | pKa = 3.0(5) | |||

| | SolubleOther = soluble in alkaline and ] solutions | |||

| | VaporPressure = >1 atm<ref name=PGCH /> | |||

| | HenryConstant = 4.01 x 10<sup>−2</sup> atm-cu m/mole | |||

| | pKa = 3.0(5)}} | |||

| | Section3 = {{Chembox Thermochemistry | |||

| | DeltaHf = 104.60 kJ/mol | |||

| | Entropy = 257.22 J K<sup>−1</sup> mol<sup>−1</sup>}} | |||

| | Section4 = {{Chembox Hazards | |||

| | ExternalMSDS = | |||

| | EUIndex = 017-026-00-3 | |||

| | EUClass = {{Hazchem O}}{{Hazchem T+}}{{Hazchem C}}{{Hazchem N}} | |||

| | RPhrases = {{R6}}, {{R8}}, {{R26}}, {{R34}}, {{R50}} | |||

| | SPhrases = {{S1/2}}, {{S23}}, {{S26}}, {{S28}}, {{S36/37/39}}, {{S38}}, {{S45}}, {{S61}} | |||

| | NFPA-H = 3 | |||

| | NFPA-F = 0 | |||

| | NFPA-R = 4 | |||

| | NFPA-O = OX | |||

| | LD50 = 292 mg/kg (oral, rat)}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| |Section3={{Chembox Thermochemistry | |||

| '''Chlorine dioxide''' is a ] with the formula ClO<sub>2</sub>. This yellowish-green ] crystallizes as bright orange crystals at −59 °C. As one of several ], it is a potent and useful ] used in water treatment and in bleaching.<ref>{{Greenwood&Earnshaw2nd|pages=844–849}}</ref> | |||

| | DeltaHf = 104.60 kJ/mol | |||

| | Entropy = 257.22 J K<sup>−1</sup> mol<sup>−1</sup>}} | |||

| |Section4={{Chembox Hazards | |||

| | MainHazards = Highly toxic, corrosive, unstable, powerful oxidizer | |||

| | ExternalSDS = . | |||

| | GHSPictograms = {{GHS flame over circle}}{{GHS corrosion}}{{GHS skull and crossbones}} | |||

| | GHSSignalWord = Danger | |||

| | HPhrases = {{H-phrases|271|314|300+310+330|H372}} | |||

| | PPhrases = {{P-phrases|210|220|280|283|260|264|271|284|301+310|304+340|306+360|305+351+338|371+380+375|403+233|405|501}} | |||

| | NFPA-H = 3 | |||

| | NFPA-F = 0 | |||

| | NFPA-R = 4 | |||

| | NFPA-S = OX | |||

| | LD50 = 94 mg/kg (oral, rat)<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dobson |first1=Stuart |last2=Cary |first2=Richard |title=Chlorine dioxide (gas) |publisher=World Health Organization. |page=4 |url=https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42421 |date =2002 | last3 = International Programme on Chemical Safety|hdl=10665/42421 |isbn=978-92-4-153037-8 |access-date=17 August 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | LCLo = 260 ppm (rat, 2 hr)<ref name=IDLH>{{IDLH|10049044|Chlorine dioxide}}</ref> | |||

| | PEL = TWA 0.1 ppm (0.3 mg/m<sup>3</sup>)<ref name=PGCH>{{PGCH|0116}}</ref> | |||

| | IDLH = 5 ppm<ref name=PGCH /> | |||

| | REL = TWA 0.1 ppm (0.3 mg/m<sup>3</sup>) ST 0.3 ppm (0.9 mg/m<sup>3</sup>)<ref name=PGCH /> | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Chlorine dioxide''' is a ] with the formula ClO<sub>2</sub> that exists as yellowish-green ] above 11 °C, a reddish-brown liquid between 11 °C and −59 °C, and as bright orange crystals below −59 °C. It is usually handled as an aqueous solution. It is commonly used as a ]. More recent developments have extended its applications in ] and as a ]. | |||

| ==Structure and bonding== | == Structure and bonding == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The molecule ClO<sub>2</sub> has an odd number of ]s, and therefore, it is a ] ]. It is an unusual "example of an odd-electron molecule stable toward dimerization" (] being another example).<ref>{{Greenwood&Earnshaw2nd|page=845}}</ref> | |||

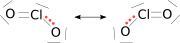

| The molecule ClO<sub>2</sub> has an odd number of valence electrons and therefore, it is a ] ]. Its electronic structure has long baffled chemists because none of the possible ]s is very satisfactory. In 1933 L.O. Brockway proposed a structure that involved a ].<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1073/pnas.19.3.303 |author=Brockway LO |title=The Three-Electron Bond in Chlorine Dioxide |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=19 |issue=3 |pages=303–7 |date=March 1933 |pmid=16577512 |pmc=1085967 |bibcode = 1933PNAS...19..303B }}</ref> Chemist ] further developed this idea and arrived at two resonance structures involving a double bond on one side and a single bond plus three-electron bond on the other.<ref>{{cite book |author=Pauling, Linus |title=General chemistry |publisher=Dover Publications, Inc |location=Mineola, NY |year=1988 |isbn=0-486-65622-5 }}</ref> In Pauling's view the latter combination should represent a bond that is slightly ''weaker'' than the double bond. In ] this idea is commonplace if the third electron is placed in an anti-bonding orbital. Later work has confirmed that the ] is indeed an incompletely-filled orbital.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1016/j.ijms.2005.12.046}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Preparation== | |||

| ClO<sub>2</sub> crystallizes in the orthorhombic ] space group.<ref>{{Cite web |title=mp-23207: ClO2 (Orthorhombic, Pbca, 61) |url=https://materialsproject.org/materials/mp-23207/ |access-date=2022-11-03 |website=Materials Project}}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is a compound that can decompose extremely violently when separated from diluting substances. As a result, preparation methods that involve producing solutions of it without going through a gas phase stage are often preferred. Arranging handling in a safe manner is essential. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| In the laboratory, ClO<sub>2</sub> is prepared by oxidation of ]:<ref>Derby, R. I.; Hutchinson, W. S. "Chlorine(IV) Oxide" Inorganic Syntheses, 1953, IV, 152-158.</ref> | |||

| In 1933, ], a graduate student of ], proposed a structure that involved a ] and two single bonds.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1073/pnas.19.3.303 |last=Brockway |first=L. O. |title=The Three-Electron Bond in Chlorine Dioxide |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=19 |issue=3 |pages=303–307 |date=March 1933 |pmid=16577512 |pmc=1085967 |bibcode = 1933PNAS...19..303B |url=http://authors.library.caltech.edu/9165/1/BROpnas33b.pdf |doi-access=free }}</ref> However, Pauling in his ''General Chemistry'' shows a double bond to one oxygen and a single bond plus a three-electron bond to the other. The valence bond structure would be represented as the resonance hybrid depicted by Pauling.<ref name=Pauling>{{cite book |page=264|last=Linus Pauling |title=General chemistry |publisher=Dover Publications |location=Mineola, New York |year=1988 |isbn=0-486-65622-5 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/generalchemistry00paul_0 }}</ref> The three-electron bond represents a bond that is ''weaker'' than the double bond. In ] this idea is commonplace if the third electron is placed in an anti-bonding orbital. Later work has confirmed that the ] is indeed an incompletely-filled antibonding orbital.<ref>{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1016/j.ijms.2005.12.046 | title = Core-level excitation and fragmentation of chlorine dioxide | year = 2006 | last1 = Flesch | first1 = R. | last2 = Plenge | first2 = J. | last3 = Rühl | first3 = E. | journal = International Journal of Mass Spectrometry | volume = 249-250 | pages = 68–76|bibcode = 2006IJMSp.249...68F }}</ref> | |||

| :2 NaClO<sub>2</sub> + Cl<sub>2</sub> → 2 ClO<sub>2</sub> + 2 NaCl | |||

| == Preparation == | |||

| Over 95% of the chlorine dioxide produced in the world today is made from sodium chlorate and is used for ]. It is produced with high efficiency by reducing ] in a strong acid solution with a suitable ] such as ], ], ] or ].<ref name="vogt2010" /> Modern technologies are based on methanol or hydrogen peroxide, as these chemistries allow the best economy and do not co-produce elemental chlorine. The overall reaction can be written; | |||

| Chlorine dioxide was first prepared in 1811 by ].<ref>Aieta, E. Marco, and James D. Berg. "A Review of Chlorine Dioxide in Drinking Water Treatment." Journal (American Water Works Association) 78, no. 6 (1986): 62-72. Accessed April 24, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41273622</ref> | |||

| The reaction of chlorine with oxygen under conditions of flash photolysis in the presence of ultraviolet light results in trace amounts of chlorine dioxide formation.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Porter |first1=George |last2=Wright |first2=Franklin J. |date=1953 |title=Studies of free radical reactivity by the methods of flash photolysis. The photochemical reaction between chlorine and oxygen |url=http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=df9531400023 |journal=Discussions of the Faraday Society |language=en |volume=14 |pages=23 |doi=10.1039/df9531400023 |issn=0366-9033}}</ref> | |||

| Chlorate + Acid + reducing agent → Chlorine Dioxide + By-products | |||

| : <chem>Cl2 + 2 O2 -> 2 ClO2 ^</chem>'''.''' | |||

| Chlorine dioxide can decompose violently when separated from diluting substances. As a result, preparation methods that involve producing solutions of it without going through a gas-phase stage are often preferred. | |||

| The reaction of ] with ] in a single reactor is believed to proceed via the following pathway: | |||

| === Oxidation of chlorite === | |||

| In the laboratory, ClO<sub>2</sub> can be prepared by oxidation of ] with chlorine:<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Derby | first1 = R. I. | last2 = Hutchinson | first2 = W. S. | chapter = Chlorine(IV) Oxide | year = 1953 | title = Inorganic Syntheses | volume = 4 | pages = 152–158 | doi=10.1002/9780470132357.ch51| isbn = 978-0-470-13235-7 }}</ref> | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|NaClO2}} + {{frac|1|2}} {{chem2|Cl2 -> ClO2 + NaCl}}}} | |||

| Traditionally, chlorine dioxide for ] applications has been made from sodium ] or the sodium chlorite–] method: | |||

| :HClO<sub>3</sub> + HCl → HClO<sub>2</sub> + HOCl | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|2 NaClO2 + 2 HCl + NaOCl -> 2 ClO2 + 3 NaCl + H2O}}}} | |||

| :HClO<sub>3</sub> + HClO<sub>2</sub> → 2 ClO<sub>2</sub> + Cl<sub>2</sub> + 2 H<sub>2</sub>O | |||

| or the sodium chlorite–] method: | |||

| :HOCl + HCl → Cl<sub>2</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|5 NaClO2 + 4 HCl -> 5 NaCl + 4 ClO2 + 2 H2O}}}} | |||

| or the chlorite–] method: | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|4 ClO2(-) + 2 H2SO4 -> 2 ClO2 + HClO3 + 2 SO4(2-) + H2O + HCl}}}} | |||

| All three methods can produce chlorine dioxide with high chlorite conversion yield. Unlike the other processes, the chlorite–sulfuric acid method is completely chlorine-free, although it suffers from the requirement of 25% more chlorite to produce an equivalent amount of chlorine dioxide. Alternatively, ] may be efficiently used in small-scale applications.<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010" /> | |||

| The commercially more important production route uses methanol as the reducing agent and sulfuric acid for the acidity. Two advantages by not using the chloride-based processes are that there is no formation of elemental chlorine, and that ], a valuable chemical for the pulp mill, is a side-product. These methanol-based processes provide high efficiency and can be made very safe.<ref name="vogt2010">{{cite doi|10.1002/14356007.a06_483.pub2}}</ref> | |||

| Addition of sulfuric acid or any strong acid to ] salts produces chlorine dioxide.<ref name=Pauling/> | |||

| A much smaller, but important, market for chlorine dioxide is for use as a disinfectant. Since 1999 a growing proportion of the chlorine dioxide made globally for water treatment and other small-scale applications has been made using the chlorate, hydrogen peroxide and sulfuric acid method, which can produce a chlorine-free product at high efficiency. Traditionally, chlorine dioxide for disinfection applications has been made by one of three methods using sodium ] or the sodium chlorite - hypochlorite method: | |||

| === Reduction of chlorate === | |||

| In the laboratory, chlorine dioxide can also be prepared by reaction of ] with ]: | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|KClO3 + H2C2O4 ->}} {{frac|1|2}} {{chem2|K2C2O4 + ClO2 + CO2 + H2O}}}} | |||

| or with oxalic and sulfuric acid: | |||

| :2 NaClO<sub>2</sub> + 2 HCl + NaOCl → 2 ClO<sub>2</sub> + 3 NaCl + H<sub>2</sub>O | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|KClO3}} + {{frac|1|2}} {{chem2|H2C2O4}} + {{chem2|H2SO4 -> KHSO4 + ClO2 + CO2 + H2O}}}} | |||

| Over 95% of the chlorine dioxide produced in the world today is made by reduction of ], for use in ]. It is produced with high efficiency in a strong acid solution with a suitable ] such as ], ], ] or ].<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010">{{Ullmann|last1=Vogt|first1=H.|last2=Balej|first2=J.|last3=Bennett|first3=J. E.|last4=Wintzer|first4=P.|last5=Sheikh|first5=S. A.|last6=Gallone|first6=P.|last7=Vasudevan|first7=S.|last8=Pelin|first8=K.|date=2010|title=Chlorine Oxides and Chlorine Oxygen Acids|DOI=10.1002/14356007.a06_483.pub2}}</ref> Modern technologies are based on methanol or hydrogen peroxide, as these chemistries allow the best economy and do not co-produce elemental chlorine. The overall reaction can be written as:<ref>{{cite conference |url=http://www.tappi.org/Downloads/unsorted/UNTITLED---ipb96453pdf.aspx |title=Mechanism of the Methanol Based ClO2 Generation Process |first1=Y. |last1=Ni |first2=X. |last2=Wang |year=1996 |publisher=] |book-title=International Pulp Bleaching Conference |pages=454–462 }}{{dead link|date=July 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| or the sodium chlorite - hydrochloric acid method: | |||

| {{block indent|chlorate + acid + reducing agent → chlorine dioxide + by-products}} | |||

| :5 NaClO<sub>2</sub> + 4 HCl → 5 NaCl + 4 ClO<sub>2</sub> + 2 H<sub>2</sub>O | |||

| As a typical example, the reaction of ] with ] in a single reactor is believed to proceed through the following pathway: | |||

| All three sodium chlorite chemistries can produce chlorine dioxide with high chlorite conversion yield, but unlike the other processes the chlorite-HCl method produces completely chlorine-free chlorine dioxide but suffers from the requirement of 25% more chlorite to produce an equivalent amount of chlorine dioxide. Alternatively, ] may efficiently be used also in small scale applications.<ref name="vogt2010" /> | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|ClO3(-) + Cl(-) + H(+) -> ClO2(-) + HOCl}}}} | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|ClO3(-) + ClO2(-) + 2 H(+) -> 2 ClO2 + H2O}}}} | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|HOCl + Cl(-) + H(+) -> Cl2 + H2O}}}} | |||

| which gives the overall reaction | |||

| Very pure chlorine dioxide can also be produced by electrolysis of a chlorite solution: | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|ClO3(-) + Cl(-) + 2 H(+) -> ClO2}} + {{frac|1|2}} {{chem2|Cl2 + H2O}}.}} | |||

| The commercially more important production route uses ] as the reducing agent and ] for the acidity. Two advantages of not using the chloride-based processes are that there is no formation of elemental chlorine, and that ], a valuable chemical for the pulp mill, is a side-product. These methanol-based processes provide high efficiency and can be made very safe.<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010"/> | |||

| :2 NaClO<sub>2</sub> + 2 H<sub>2</sub>O → 2 ClO<sub>2</sub> + 2 NaOH + H<sub>2</sub> | |||

| The variant process using sodium chlorate, hydrogen peroxide and sulfuric acid has been increasingly used since 1999 for water treatment and other small-scale ] applications, since it produce a chlorine-free product at high efficiency, over 95%.{{cn|date=September 2022}} | |||

| High purity chlorine dioxide gas (7.7% in air or nitrogen) can be produced by the Gas:Solid method, which reacts dilute chlorine gas with solid sodium chlorite. | |||

| === Other processes === | |||

| :2 NaClO<sub>2</sub> + Cl<sub>2</sub> → 2 ClO<sub>2</sub> + 2 NaCl | |||

| Very pure chlorine dioxide can also be produced by electrolysis of a chlorite solution:<ref name=white>{{cite book |last1=White |first1=George W. |first2=Geo Clifford |last2=White |title=The handbook of chlorination and alternative disinfectants |publisher=John Wiley |location=New York |year=1999 |isbn=0-471-29207-9 |edition=4th}}</ref> | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|NaClO2 + H2O -> ClO2 + NaOH}} + {{frac|1|2}} {{chem2|H2}}}} | |||

| These processes and several slight variations have been reviewed.<ref>{{cite book |author=White, George W.; Geo Clifford White |title=The handbook of chlorination and alternative disinfectants |publisher=John Wiley |location=New York |year=1999 |isbn=0-471-29207-9 |edition=4th}}</ref> | |||

| High-purity chlorine dioxide gas (7.7% in air or nitrogen) can be produced by the gas–solid method, which reacts dilute chlorine gas with solid sodium chlorite:<ref name=white/> | |||

| ==Handling properties== | |||

| {{block indent|{{chem2|NaClO2}} + {{frac|1|2}} {{chem2|Cl2 -> ClO2 + NaCl}}}} | |||

| At gas phase concentrations greater than 30% volume in air at ] (more correctly: at partial pressures above 10 kPa <ref name="vogt2010" />), ClO<sub>2</sub> may explosively decompose into ] and ]. The decomposition can be initiated by, for example, light, hot spots, chemical reaction, or pressure shock. Thus, chlorine dioxide gas is never handled in concentrated form, but is almost always handled as a dissolved gas in water in a concentration range of 0.5 to 10 grams per liter. Its solubility increases at lower temperatures: it is thus common to use chilled water (5 °C or 41 °F) when storing at concentrations above 3 grams per liter. In many countries, such as the ], chlorine dioxide gas may not be transported at any concentration and is almost always produced at the application site using a chlorine dioxide generator.<ref name="vogt2010" /> In some countries, chlorine dioxide solution below 3 grams per liter in concentration may be transported by land, but are relatively unstable and deteriorate quickly. | |||

| == Handling properties == | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is very different from elemental chlorine.<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010"/> One of the most important qualities of chlorine dioxide is its high water solubility, especially in cold water. Chlorine dioxide does not ]; it remains a dissolved gas in solution. Chlorine dioxide is approximately 10 times more soluble in water than elemental chlorine<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010" /> but its solubility is very temperature-dependent. | |||

| At partial pressures above {{Convert|10|kPa|psi|abbr=on}}<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010" /> (or gas-phase concentrations greater than 10% volume in air at ]) of ClO<sub>2</sub> may explosively ] into ] and ]. The decomposition can be initiated by light, hot spots, chemical reaction, or pressure shock. Thus, chlorine dioxide is never handled as a pure gas, but is almost always handled in an aqueous solution in concentrations between 0.5 to 10 grams per liter. Its solubility increases at lower temperatures, so it is common to use chilled water (5 °C, 41 °F) when storing at concentrations above 3 grams per liter. In many countries, such as the United States, chlorine dioxide may not be transported at any concentration and is instead almost always produced on-site.<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010" /> In some countries,{{which|date=April 2022}} chlorine dioxide solutions below 3 grams per liter in concentration may be transported by land, but they are relatively unstable and deteriorate quickly. | |||

| ==Uses== | ==Uses== | ||

| Chlorine dioxide is used |

Chlorine dioxide is used for ] and for the ] (called ]) of municipal drinking water,<ref>{{cite book| title = Inorganic Chemistry: An Industrial and Environmental Perspective| url = https://archive.org/details/inorganicchemist00swad_535| url-access = limited| first = Thomas Wilson | last = Swaddle| publisher = Academic Press| year = 1997| isbn = 0-12-678550-3| pages = –199 | ||

| }}</ref><ref name="epa1999">{{citation |title=Alternative Disinfectants and Oxidants Manual, chapter 4: Chlorine Dioxide |publisher=US Environmental Protection Agency: Office of Water |url=https://www.epa.gov/safewater/mdbp/pdf/alter/chapt_4.pdf |date=April 1999 |access-date=2009-11-27 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150905194840/https://www.epa.gov/safewater/mdbp/pdf/alter/chapt_4.pdf |archive-date= 2015-09-05}}</ref>{{rp|4-1}}<ref name="block2001" /> treatment of water in oil and gas applications, disinfection in the food industry, microbiological control in cooling towers, and textile bleaching.<ref name="Simpson">{{cite book |last1=Simpson |first1=Gregory Deward |title=Practical Chlorine Dioxide |date=2005 |publisher=Greg D. Simpson & Associates |location=Colleyville, Texas |isbn=0-9771985-0-2 | edition=Volume 1 }}</ref> As a disinfectant, it is effective even at low concentrations because of its unique qualities.<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010" /><ref name="epa1999"/><ref name="Simpson"/> | |||

| | title = Inorganic chemistry: an industrial and environmental perspective | |||

| | author = Thomas Wilson Swaddle | |||

| | publisher = Academic Press | |||

| | year = 1997 | |||

| | isbn = 0-12-678550-3 | |||

| | pages = 198–199 | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="epa1999">{{citation | title = EPA Guidance Manual, chapter 4: Chlorine dioxide | publisher = US Environmental Protection Agency | url = http://www.epa.gov/ogwdw/mdbp/pdf/alter/chapt_4.pdf | accessdate = 2009-11-27 }}</ref>{{rp|4-1}}<ref name="block2001" /> | |||

| ===Bleaching=== | === Bleaching === | ||

| Chlorine dioxide is sometimes used for |

Chlorine dioxide is sometimes used for bleaching of wood pulp in combination with chlorine, but it is used alone in ECF (elemental chlorine-free) bleaching sequences. It is used at moderately acidic ] (3.5 to 6). The use of chlorine dioxide minimizes the amount of ] compounds produced.<ref name="eero">{{cite book | ||

| | |

| first= E. |last=Sjöström | ||

| |title= Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications | | title= Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications | ||

| |publisher= ] | | publisher= ] | ||

| |year= 1993 | | year= 1993 | ||

| |isbn= 0-12-647480-X | | isbn= 0-12-647480-X | ||

| |oclc= 58509724}}</ref> Chlorine dioxide (ECF technology) currently is the most important |

| oclc= 58509724}}</ref> Chlorine dioxide (ECF technology) currently is the most important ]ing method worldwide. About 95% of all bleached ] is made using chlorine dioxide in ECF bleaching sequences.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aet.org/science_of_ecf/eco_risk/2005_pulp.html|title=AET – Reports – Science – Trends in World Bleached Chemical Pulp Production: 1990–2005|access-date=2016-02-26|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170730101540/http://www.aet.org/science_of_ecf/eco_risk/2005_pulp.html|archive-date=2017-07-30|url-status=dead}}</ref> | ||

| Chlorine dioxide has been used to bleach ].<ref>{{cite journal | title = Maturing and Bleaching Agents in Producing Flour | first = C. G. | last = Harrel | journal = Industrial & Engineering Chemistry | date = 1952 | volume = 44 | issue = 1 | pages = 95–100 | doi = 10.1021/ie50505a030 }}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is also used for the ]ing of ]. | |||

| ===Water |

=== Water treatment === | ||

| {{Further|Water chlorination |

{{Further|Water chlorination|Portable water purification#Chlorine dioxide}} | ||

| The ] |

The water treatment plant at ] first used chlorine dioxide for ] treatment in 1944 for destroying "taste and odor producing ]."<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4-17}}<ref name="block2001" /> Chlorine dioxide was introduced as a drinking water disinfectant on a large scale in 1956, when ], Belgium, changed from chlorine to chlorine dioxide.<ref name="block2001" /> Its most common use in water treatment is as a pre-] prior to chlorination of drinking water to destroy natural water impurities that would otherwise produce ]s upon exposure to free chlorine.<ref>{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1016/j.desal.2004.10.022 | title = Trihalomethane formation during chemical oxidation with chlorine, chlorine dioxide and ozone of ten Italian natural waters | year = 2005 | last1 = Sorlini | first1 = S. | last2 = Collivignarelli | first2 = C. | journal = Desalination | volume = 176| issue = 1–3| pages = 103–111 | bibcode = 2005Desal.176..103S }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | pmid = 8758861 | title = A pilot study on trihalomethane formation in water treated by chlorine dioxide |lang=zh | last1 = Li |first1=J. | last2 = Yu |first2=Z. | last3 = Gao |first3=M. | journal = Zhonghua Yufang Yixue Zazhi (Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine) | volume = 30 | issue = 1 | pages = 10–13 | year = 1996 }}</ref><ref name="volk2002">{{cite journal | title = Implementation of chlorine dioxide disinfection: Effects of the treatment change on drinking water quality in a full-scale distribution system | first1= C. J. |last1=Volk | first2 = R. |last2=Hofmann | first3 = C. |last3=Chauret | first4 = G. A. |last4=Gagnon | first5 = G. |last5=Ranger | first6 = R. C. |last6=Andrews | journal = Journal of Environmental Engineering and Science | volume = 1 | issue = 5 | pages = 323–330 | year = 2002 | doi = 10.1139/s02-026 | bibcode= 2002JEES....1..323V }}</ref> Trihalomethanes are suspected carcinogenic disinfection by-products<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.2307/3429432 | journal = Environmental Health Perspectives | year = 1982 | title = Trihalomethanes as initiators and promoters of carcinogenesis | first1= M. A. |last1=Pereira | first2 = L. H.|last2= Lin | first3 = J. M. |last3=Lippitt | first4 = S. L. |last4=Herren | volume = 46 | pmc = 1569022 | pages = 151–156 | pmid = 7151756 | jstor = 3429432 }}</ref> associated with chlorination of naturally occurring organics in raw water.<ref name="volk2002" /> Chlorine dioxide also produces 70% fewer halomethanes in the presence of natural organic matter compared to when elemental chlorine or bleach is used.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|title=Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edition, incorporating the 1st addendum|url=https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241549950|access-date=2021-11-29|publisher=]|language=en}}</ref> | ||

| Chlorine dioxide is also superior to chlorine when operating above ] 7,<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4-33}} in the presence of ammonia and amines,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Chlorine dioxide as a disinfectant|url=https://www.lenntech.com/processes/disinfection/chemical/disinfectants-chlorine-dioxide.htm|access-date=2021-11-25|publisher=Lenntech}}</ref> and for the control of biofilms in water distribution systems.<ref name="volk2002" /> Chlorine dioxide is used in many industrial water treatment applications as a ], including ], process water, and food processing.<ref>{{Cite journal | first5 = D.| last5 = Park | first4 = R.| journal = Food Microbiology | volume = 19| pages = 261–267 | issue = 4| last4 = Grodner | first3 = R. | last1 = Andrews | year = 2002 | title = Chlorine dioxide wash of shrimp and crawfish an alternative to aqueous chlorine | first1 = L. | last2 = Key| last3 = Martin | first2 = A. | doi = 10.1006/fmic.2002.0493 }}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is less corrosive than chlorine and superior for the control of ] bacteria.<ref name="block2001">{{cite book | title = Disinfection, sterilization, and preservation | author = Seymour Stanton Block | edition = 5th | publisher = Lippincott Williams & Wilkins | year = 2001 | isbn = 0-683-30740-1 | page = 215 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal = Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology | volume = 28 | issue = 8 | year = 2007 | title = Safety and Efficacy of Chlorine Dioxide for ''Legionella'' control in a Hospital Water System | author1 = Zhe Zhang | author2 = Carole McCann | author3 = Janet E. Stout | author4 = Steve Piesczynski | author5 = Robert Hawks | author6 = Radisav Vidic | author7 = Victor L. Yu | url = http://www.legionella.org/ZhangICHE07.pdf | accessdate = 2009-11-27 }}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is superior to some other secondary water disinfection methods in that chlorine dioxide: 1) is an EPA registered biocide, 2) is not negatively impacted by pH 3) does not lose efficacy over time (the bacteria will not grow resistant to it) and 4) is not negatively impacted by silica and phosphate, which are commonly used potable water corrosion inhibitors. | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is less corrosive than chlorine and superior for the control of '']'' bacteria.<ref name="block2001">{{cite book | title = Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation | first= Seymour Stanton |last=Block | edition = 5th | publisher = Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins | year = 2001 | isbn = 0-683-30740-1 | page = 215}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal = Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology | volume = 28 | issue = 8 | pages = 1009–1012 | year = 2007 | title = Safety and Efficacy of Chlorine Dioxide for ''Legionella'' control in a Hospital Water System | first1 = Zhe | last1 = Zhang | first2 = Carole | last2 = McCann | first3 = Janet E. | last3 = Stout | first4 = Steve | last4 = Piesczynski | first5 = Robert | last5 = Hawks | first6 = Radisav | last6 = Vidic | first7 = Victor L. | last7 = Yu | url = http://www.legionella.org/ZhangICHE07.pdf | access-date = 2009-11-27 | doi = 10.1086/518847 | pmid = 17620253 | s2cid = 40554616 | archive-date = 2011-07-19 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110719125409/http://www.legionella.org/ZhangICHE07.pdf | url-status = dead }}</ref> | |||

| It is more effective as a disinfectant than chlorine in most circumstances against water borne pathogenic microbes such as ]es,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ogata N, Shibata T |title=Protective effect of low-concentration chlorine dioxide gas against influenza A virus infection |journal=J. Gen. Virol. |volume=89 |issue=Pt 1 |pages=60–7 |date=January 2008 |pmid=18089729 |doi=10.1099/vir.0.83393-0 |url=http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/89/1/60?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&author1=ogata+n&andorexactfulltext=and&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&sortspec=relevance&resourcetype=HWCIT}}</ref> ] and ] – including the ]s of '']'' and the ]s of '']''.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4-20–4-21}} | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is superior to some other secondary water disinfection methods, in that chlorine dioxide is not negatively impacted by pH, does not lose efficacy over time, because the bacteria will not grow resistant to it, and is not negatively impacted by ] and ]s, which are commonly used potable water corrosion inhibitors. In the United States, it is an ]-registered biocide. | |||

| It is more effective as a disinfectant than chlorine in most circumstances against waterborne pathogenic agents such as ]es,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ogata |first1=N. |last2=Shibata |first2=T. |title=Protective effect of low-concentration chlorine dioxide gas against influenza A virus infection |journal=Journal of General Virology |volume=89 |issue=pt 1 |pages=60–67 |date=January 2008 |pmid=18089729 |doi=10.1099/vir.0.83393-0 |doi-access=free }}</ref> ], and ] – including the ] of '']'' and the ]s of '']''.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4-20–4-21}} | |||

| The use of chlorine dioxide in water treatment leads to the formation of the by-product chlorite, which is currently limited to a maximum of 1 ppm in drinking water in the USA.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4–33}} This EPA standard limits the use of chlorine dioxide in the USA to relatively high quality water or water, which is to be treated with iron based coagulants (Iron can reduce chlorite to chloride).{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} | |||

| The use of chlorine dioxide in water treatment leads to the formation of the by-product chlorite, which is currently limited to a maximum of 1 part per million in drinking water in the USA.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4-33}} This EPA standard limits the use of chlorine dioxide in the US to relatively high-quality water, because this minimizes chlorite concentration, or water that is to be treated with iron-based coagulants, because iron can reduce chlorite to chloride.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Chlorine Dioxide & Chlorite {{!}} Public Health Statement {{!}} ATSDR|url=https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/PHS/PHS.aspx?phsid=580&toxid=108|access-date=2021-11-25|location=United States|publisher=]}}</ref> The World Health Organization also advises a 1ppm dosification.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| ===Other disinfection uses=== | |||

| It can also be used for air disinfection,<ref>{{cite journal | journal = Journal of Environment and Health | volume = 24 | issue = 4 | pages = 245–246 | title = Air Disinfection with Chlorine Dioxide in Saps | author1 = Zhang, Y. L. | author2 = Zheng, S. Y. | author3 = Zhi, Q. | year = 2007 | url = http://www.csa.com/partners/viewrecord.php?requester=gs&collection=TRD&recid=07519213EN }}</ref> and was the principal agent used in the decontamination of buildings in the United States after the ].<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.epa.gov/opp00001/factsheets/chemicals/chlorinedioxidefactsheet.htm | title = Anthrax spore decontamination using chlorine dioxide | accessdate = 2009-11-27 | publisher = United States Environmental Protection Agency | year = 2007 }}</ref> After the disaster of ] in ], ] and the surrounding Gulf Coast, chlorine dioxide has been used to eradicate dangerous ] from houses inundated by the flood-water.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Efficacy of Gaseous Chlorine Dioxide as a Sanitizer for Killing Salmonella, Yeasts, and Molds on Blueberries, Strawberries, and Raspberries | publisher = International Association for Food Protection | journal = Journal of Food Protection | volume = 68 | issue = 6 | year = 2005 | pages = 1165–1175 | author1 = Sy, Kaye V. | author2 = McWatters, Kay H. | author3 = Beuchat, Larry R. | url = http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iafp/jfp/2005/00000068/00000006/art00007 | pmid = 15954703 }}</ref> Sometimes it is used as a fumigant treatment to 'sanitize' fruits such as blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries that develop molds and yeast. | |||

| === Use in public crises === | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is used for the disinfection of ], such as, under the trade name ''{{visible anchor|Tristel}}''.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1053/jhin.2001.0956}}</ref> It is also available in a "trio" consisting of a preceding "pre-clean" with ] and a succeeding "rinse" with deionised water and low-level antioxidant.<ref> Product Information at ''Ethical Agents'', retrieved Nov 2012</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide has many applications as an oxidizer or disinfectant.<ref name="Vogt, H. 2010" /> Chlorine dioxide can be used for air disinfection<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Zhang|first1=Y.-L.|last2=Zheng|first2=S.-Y.|last3=Zhi|first3=Q.|year=2007|title=Air Disinfection with Chlorine Dioxide in Saps|url=http://www.csa.com/partners/viewrecord.php?requester=gs&collection=TRD&recid=07519213EN|journal=Journal of Environment and Health|volume=24|issue=4|pages=245–246}}</ref> and was the principal agent used in the decontamination of buildings in the United States after the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.epa.gov/opp00001/factsheets/chemicals/chlorinedioxidefactsheet.htm|title=Anthrax spore decontamination using chlorine dioxide|year=2007|location=United States|publisher=Environmental Protection Agency|access-date=2009-11-27}}</ref> After the disaster of ] in ], ], and the surrounding Gulf Coast, chlorine dioxide was used to eradicate dangerous ] from houses inundated by the flood water.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Sy|first1=Kaye V.|last2=McWatters|first2=Kay H.|last3=Beuchat|first3=Larry R.|year=2005|title=Efficacy of Gaseous Chlorine Dioxide as a Sanitizer for Killing Salmonella, Yeasts, and Molds on Blueberries, Strawberries, and Raspberries|journal=Journal of Food Protection|publisher=International Association for Food Protection|volume=68|issue=6|pages=1165–1175|doi=10.4315/0362-028x-68.6.1165|pmid=15954703|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, the ] has posted a list of many ] that meet its criteria for use in environmental measures against the causative ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://cen.acs.org/biological-chemistry/infectious-disease/How-we-know-disinfectants-should-kill-the-COVID-19-coronavirus/98/web/2020/03|title=How we know disinfectants should kill the COVID-19 coronavirus|website=Chemical & Engineering News|language=en|access-date=2020-03-28}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2|title=List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2|date=2020-03-13|location=United States|website=]|language=en|access-date=2020-03-28}}</ref> Some are based on ] that is activated into chlorine dioxide, though differing formulations are used in each product. Many other products on the EPA list contain ], which is similar in name but should not be confused with sodium chlorite because they have very different modes of chemical action. | |||

| Chlorine dioxide also is used for control of ] and ]s in water intakes.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4–34}} | |||

| === Other disinfection uses === | |||

| Chlorine dioxide also was shown to be effective in ] eradication.<ref> Department of Environmental, Agricultural and Occupational Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide may be used as a fumigant treatment to "sanitize" fruits such as blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries that develop molds and yeast.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = O'Brian | |||

| | first = D. | |||

| | title = Chlorine Dioxide Pouches Can Make Produce Safer and Reduce Spoilage | |||

| | journal = AgResearch Magazine | |||

| | publisher =USDA Agricultural Research Service | |||

| | date = 2017 | |||

| | issue = July | |||

| | url = https://www.ars.usda.gov/news-events/news/research-news/2017/chlorine-dioxide-pouches-can-make-produce-safer-and-reduce-spoilage/ | |||

| | access-date = 2018-06-21 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide may be used to disinfect poultry by spraying or immersing it after slaughtering.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.bigissue.com/latest/the-truth-behind-the-chlorinated-chicken-panic/|title=The truth behind the chlorinated chicken panic|date=2019-05-29|website=The Big Issue|language=en|access-date=2020-02-05}}</ref> | |||

| ===Other uses=== | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is used as an oxidant for phenol destruction in waste water streams and for odor control in the air scrubbers of animal byproduct (rendering) plants.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4–34}} It is also available for use as a deodorant for cars and boats, packaged as a chlorine dioxide generating package activated by water, and left in the boat/car overnight. | |||

| Chlorine dioxide may be used for the disinfection of ], such as under the trade name Tristel.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Coates | first1 = D. | title = An evaluation of the use of chlorine dioxide (Tristel One-Shot) in an automated washer/disinfector (Medivator) fitted with a chlorine dioxide generator for decontamination of flexible endoscopes | doi = 10.1053/jhin.2001.0956 | journal = Journal of Hospital Infection | volume = 48 | issue = 1 | pages = 55–65 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11358471}}</ref> It is also available in a trio consisting of a preceding pre-clean with ] and a succeeding rinse with ] and a low-level antioxidant.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ethicalagents.co.nz/ProductPDF/Tristel-Trio-Wipe-System.pdf |title=Tristel Wipes System Product Information |website=Ethical Agents |access-date=2012-11-01 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160415120703/http://www.ethicalagents.co.nz/ProductPDF/Tristel-Trio-Wipe-System.pdf |archive-date=2016-04-15 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ==Red Cross Malaria cure controversy== | |||

| The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies strongly dissociate themselves from a water purification study that took place in Uganda of 2012 where Sodium chlorite 22.4% was used. In the study it was concluded that all 154 cases testing positive for Malaria out of the 800 cases tested in total, tested negative after being given the solution in its activated form (Cl02). <ref>{{cite press release |publisher= ] |date= May 15, 2013 |title= IFRC strongly dissociates from the claim of a ‘miracle’ solution to defeat malaria |url= http://www.ifrc.org/en/news-and-media/opinions-and-positions/opinion-pieces/2013/ifrc-strongly-dissociates-from-the-claim-of-a-miracle-solution-to-defeat-malaria/ |accessdate= October 25, 2014 }}</ref> <ref>{{cite press release |publisher= ] |date= July 29, 2013 |title= Proof: MMS cures malaria, despite Red Cross cover-up |url= http://www.naturalnews.com/041392_master_mineral_solution_malaria_cure_red_cross.html |accessdate= October 25, 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide may be used for control of ] and ]s in water intakes.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4-34}} | |||

| ==Safety issues in water and supplements== | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is toxic, hence limits on exposure to it are needed to ensure its safe use. The ] has set a maximum level of 0.8 mg/L for chlorine dioxide in drinking water.<ref>{{cite web|title=ATSDR: ToxFAQs™ for Chlorine Dioxide and Chlorite|url=http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/tf.asp?id=581&tid=108}}</ref> The ] (OSHA), an agency of the ], has set an 8 hour ] of 0.1 ppm in air (0.3 milligrams per cubic meter (mg/m<sup>3</sup>) for people working with chlorine dioxide.<ref>{{cite web |title=Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Chlorine Dioxide |url=http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/healthguidelines/chlorinedioxide/recognition.html |accessdate=Dec 8, 1012}}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide was shown to be effective in ] eradication.<ref>{{cite journal | pmid = 22476276 | doi=10.1086/665320 | volume=33 | issue=5 | title=Gaseous chlorine dioxide as an alternative for bedbug control | journal=Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology | pages=495–9 | last1 = Gibbs | first1 = S. G. | last2 = Lowe | first2 = J. J. | last3 = Smith | first3 = P. W. | last4 = Hewlett | first4 = A. L.| s2cid=14105046 | year=2012 }}</ref> | |||

| On July 30, 2010 and again on October 1, 2010, the ] (FDA), warned against the use of the product "]" or "MMS", which when made up according to instructions produces chlorine dioxide. MMS has been marketed as a treatment for a variety of conditions, including HIV, cancer, autism, and acne. The FDA warnings informed consumers that MMS can cause serious harm to health, and stated that it has received numerous reports of nausea, severe vomiting, and life-threatening low blood pressure caused by dehydration,<ref></ref><ref>http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm228052.htm</ref> among other symptoms, such as diarrhea. | |||

| For water purification during ], disinfecting tablets containing chlorine dioxide are more effective against pathogens than those using household bleach, but typically cost more.<ref>{{cite web |title= How to Treat Backcountry Water on the Cheap |last= Langlois |first= Krista |date= March 13, 2018 |work= Sierra |publisher= ] |url= https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/how-treat-backcountry-water-cheap |access-date= 2021-02-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title= A Guide to Drinking Water Treatment and Sanitation for Backcountry & Travel Use |date= April 10, 2009 |location=United States |publisher=] |url= https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/travel/backcountry_water_treatment.html |access-date= 2021-02-10}}</ref> | |||

| === Other uses === | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is used as an oxidant for destroying ] in ] streams and for odor control in the air scrubbers of animal byproduct (rendering) plants.<ref name="epa1999" />{{rp|4-34}} It is also available for use as a deodorant for cars and boats, in chlorine dioxide-generating packages that are activated by water and left in the boat or car overnight. | |||

| In dilute concentrations, chlorine dioxide is an ingredient that acts as an antiseptic agent in some ]es.<ref name="pmid32410557">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kerémi B, Márta K, Farkas K, Czumbel LM, Tóth B, Szakács Z, Csupor D, Czimmer J, Rumbus Z, Révész P, Németh A, Gerber G, Hegyi P, Varga G |title=Effects of Chlorine Dioxide on Oral Hygiene - A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis |journal=Current Pharmaceutical Design |volume=26 |issue=25 |pages=3015–3025 |date=2020 |pmid=32410557 |pmc=8383470 |doi=10.2174/1381612826666200515134450}}</ref><ref name="pmid36634129">{{cite journal |vauthors=Szalai E, Tajti P, Szabó B, Hegyi P, Czumbel LM, Shojazadeh S, Varga G, Németh O, Keremi B |title=Daily use of chlorine dioxide effectively treats halitosis: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=e0280377 |date=2023 |pmid=36634129 |pmc=9836286 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0280377|doi-access=free |bibcode=2023PLoSO..1880377S }}</ref> | |||

| == Safety issues in water and supplements == | |||

| Potential hazards with chlorine dioxide include poisoning and the risk of spontaneous ignition or explosion on contact with flammable materials.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp160.pdf|title=Toxicological Profile for Chlorine Dioxide and Chlorite|publisher=Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, US HHS|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190614173335/http://atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp160.pdf|archive-date=2019-06-14}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=López |first1=María I. |last2=Croce |first2=Adela E. |last3=Sicre |first3=Juan E. |date=1994 |title=Explosive decomposition of gaseous chlorine dioxide |url=http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=FT9949003391 |journal=J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. |language=en |volume=90 |issue=22 |pages=3391–3396 |doi=10.1039/FT9949003391 |issn=0956-5000}}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide is toxic, and limits on human exposure are required to ensure its safe use. The ] has set a maximum level of 0.8 mg/L for chlorine dioxide in drinking water.<ref>{{cite web|title=ATSDR: ToxFAQs™ for Chlorine Dioxide and Chlorite|url=https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/ToxFAQs/ToxFAQsLanding.aspx?id=581&tid=108}}</ref> The ] (OSHA), an agency of the ], has set an 8-hour ] of 0.1 ppm in air (0.3 ]/]) for people working with chlorine dioxide.<ref>{{cite web |title=Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Chlorine Dioxide |url=http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/healthguidelines/chlorinedioxide/recognition.html |access-date=2012-12-08 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121204035804/http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/healthguidelines/chlorinedioxide/recognition.html |archive-date=2012-12-04 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Chlorine dioxide has been fraudulently and illegally marketed as an ingestible cure for a wide range of diseases, including childhood autism<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/internet/moms-go-undercover-fight-fake-autism-cures-private-facebook-groups-n1007871|title=Parents are poisoning their children with bleach to 'cure' autism. These moms are trying to stop it.|website=NBC News|date=May 21, 2019 |language=en|access-date=2019-05-21}}</ref> and ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/nation/2020/01/31/fake-news-corona-virus/41121279/|title=Fake news: Chlorine dioxide won't stop coronavirus|website=Detroit News|language=en|access-date=2020-04-03}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Friedman|first=Lisa|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/03/climate/epa-fake-coronavirus-cleaners.html|title=E.P.A. Threatens Legal Action Against Sellers of Fake Coronavirus Cleaners|date=2020-04-03|work=The New York Times|access-date=2020-04-03|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2020/02/14/there-cure-coronavirus-no-do-not-drink-chlorine-dioxide/4751565002/|title=Those coronavirus 'cures' you're hearing about? They're fake. Don't drink chlorine dioxide.|last=Spencer|first=Sarnac Hale|website=USA TODAY|language=en-US|access-date=2020-04-03}}</ref> Children who have been given ] of chlorine dioxide as a supposed cure for childhood autism have suffered life-threatening ailments.<ref name=":0" /> The ] (FDA) has stated that ingestion or other internal use of chlorine dioxide, outside of supervised oral rinsing using dilute concentrations, has no health benefits of any kind, and it should not be used internally for any reason.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/drinking-bleach-will-not-cure-cancer-or-autism-fda-warns-n1041636|title=Drinking bleach will not cure cancer or autism, FDA warns|website=NBC News|date=August 12, 2019 |language=en|access-date=2019-08-13}}</ref><ref name="FDA 2019"/> | |||

| === Pseudomedicine === | |||

| {{Main article|Miracle Mineral Supplement}} | |||

| On 30 July and 1 October 2010, the United States Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of the product "]", or "MMS", which when prepared according to the instructions produces chlorine dioxide. MMS has been marketed as a treatment for a variety of conditions, including HIV, cancer, ], acne, and, more recently, ]. Many have complained to the ], reporting life-threatening reactions,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://abc7news.com/news/group-of-socal-parents-secretly-try-to-cure-kids-with-autism-using-bleach/1578833/ |title=Group of SoCal parents secretly try to cure kids with autism using bleach |first=Lisa |last=Bartley |date=2016-10-29 |work=ABC 7 News |publisher=] |access-date=2019-03-24 }}</ref> and even death.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jul/13/fake-cures-autism-prove-deadly |title=The fake cures for autism that can prove deadly |first=Frances |last=Ryan |date=2016-07-13 |work=] |access-date=2019-03-24 }}</ref> The FDA has warned consumers that MMS can cause serious harm to health, and stated that it has received numerous reports of nausea, diarrhea, severe vomiting, and life-threatening low blood pressure caused by dehydration.<ref>{{cite web|archive-url=https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170112005302/https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2010/ucm220747.htm|url=https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2010/ucm220747.htm|title=Press Announcements – FDA Warns Consumers of Serious Harm from Drinking Miracle Mineral Solution (MMS)|website=]|archive-date=2017-01-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|archive-url=https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20171101112353/https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm228052.htm|archive-date=2017-11-01|url=https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm228052.htm|title='Miracle' Treatment Turns into Potent Bleach|publisher=U.S. Food and Drug Administration|date=2015-11-20|access-date=2017-12-06|url-status=live}}</ref> This warning was repeated for a third time on 12 August 2019, and a fourth on 8 April 2020, stating that ingesting MMS is just as hazardous as ingesting bleach, and urging consumers not to use them or give these products to their children for any reason, as there is no scientific evidence showing that chlorine dioxide has any beneficial medical properties.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm220747.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110203232945/https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm220747.htm|url-status=dead|archive-date=2011-02-03|title=FDA Warns Consumers of Serious Harm from Drinking Miracle Mineral Solution (MMS)|location=United States|publisher=]|date=2011-02-03|access-date=2018-04-05}}</ref><ref name="FDA 2019">{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-warns-consumers-about-dangerous-and-potentially-life-threating-side-effects-miracle-mineral|title=FDA warns consumers about the dangerous and potentially life threatening side effects of Miracle Mineral Solution|location=United States|publisher=]|date=2019-08-12|language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190814102219/https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-warns-consumers-about-dangerous-and-potentially-life-threating-side-effects-miracle-mineral|archive-date=2019-08-14|access-date=2019-08-16}}</ref> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist| |

{{reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==External links== | |||

| *{{Commonscatinline|lcfirst=1}} | |||

| {{Chlorine compounds}} | {{Chlorine compounds}} | ||

| {{Oxides}} | {{Oxides}} | ||

| {{E number infobox 920-929}} | {{E number infobox 920-929}} | ||

| {{oxygen compounds}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Chlorine Dioxide}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:07, 9 December 2024

Chemical compoundNot to be confused with the chlorite ion or dichlorine dioxide. "E926" redirects here. For the furry-themed website e926, see e621 (website).

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name Chlorine dioxide | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

| CAS Number | |||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.135 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| Gmelin Reference | 1265 | ||

| MeSH | Chlorine+dioxide | ||

| PubChem CID | |||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 9191 | ||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

| Chemical formula | ClO2 | ||

| Molar mass | 67.45 g·mol | ||

| Appearance | Yellow to reddish gas | ||

| Odor | Acrid | ||

| Density | 2.757 g dm | ||

| Melting point | −59 °C (−74 °F; 214 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 11 °C (52 °F; 284 K) | ||

| Solubility in water | 8 g/L at 20 °C | ||

| Solubility | Soluble in alkaline solutions and sulfuric acid | ||

| Vapor pressure | >1 atm | ||

| Henry's law constant (kH) |

4.01×10 atm m mol | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.0(5) | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

| Std molar entropy (S298) |

257.22 J K mol | ||

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH298) |

104.60 kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

| Main hazards | Highly toxic, corrosive, unstable, powerful oxidizer | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| Pictograms |

| ||

| Signal word | Danger | ||

| Hazard statements | H271, H300+H310+H330, H314, H372 | ||

| Precautionary statements | P210, P220, P260, P264, P271, P280, P283, P284, P301+P310, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P306+P360, P371+P380+P375, P403+P233, P405, P501 | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

| ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

| LD50 (median dose) | 94 mg/kg (oral, rat) | ||

| LCLo (lowest published) | 260 ppm (rat, 2 hr) | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

| PEL (Permissible) | TWA 0.1 ppm (0.3 mg/m) | ||

| REL (Recommended) | TWA 0.1 ppm (0.3 mg/m) ST 0.3 ppm (0.9 mg/m) | ||

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 5 ppm | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Safety Data Sheet Archive. | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |||

Chlorine dioxide is a chemical compound with the formula ClO2 that exists as yellowish-green gas above 11 °C, a reddish-brown liquid between 11 °C and −59 °C, and as bright orange crystals below −59 °C. It is usually handled as an aqueous solution. It is commonly used as a bleach. More recent developments have extended its applications in food processing and as a disinfectant.

Structure and bonding

The molecule ClO2 has an odd number of valence electrons, and therefore, it is a paramagnetic radical. It is an unusual "example of an odd-electron molecule stable toward dimerization" (nitric oxide being another example).

ClO2 crystallizes in the orthorhombic Pbca space group.

History

In 1933, Lawrence O. Brockway, a graduate student of Linus Pauling, proposed a structure that involved a three-electron bond and two single bonds. However, Pauling in his General Chemistry shows a double bond to one oxygen and a single bond plus a three-electron bond to the other. The valence bond structure would be represented as the resonance hybrid depicted by Pauling. The three-electron bond represents a bond that is weaker than the double bond. In molecular orbital theory this idea is commonplace if the third electron is placed in an anti-bonding orbital. Later work has confirmed that the highest occupied molecular orbital is indeed an incompletely-filled antibonding orbital.

Preparation

Chlorine dioxide was first prepared in 1811 by Sir Humphry Davy.

The reaction of chlorine with oxygen under conditions of flash photolysis in the presence of ultraviolet light results in trace amounts of chlorine dioxide formation.

- .

Chlorine dioxide can decompose violently when separated from diluting substances. As a result, preparation methods that involve producing solutions of it without going through a gas-phase stage are often preferred.

Oxidation of chlorite

In the laboratory, ClO2 can be prepared by oxidation of sodium chlorite with chlorine:

NaClO2 + 1⁄2 Cl2 → ClO2 + NaClTraditionally, chlorine dioxide for disinfection applications has been made from sodium chlorite or the sodium chlorite–hypochlorite method:

2 NaClO2 + 2 HCl + NaOCl → 2 ClO2 + 3 NaCl + H2Oor the sodium chlorite–hydrochloric acid method:

5 NaClO2 + 4 HCl → 5 NaCl + 4 ClO2 + 2 H2Oor the chlorite–sulfuric acid method:

4 ClO−2 + 2 H2SO4 → 2 ClO2 + HClO3 + 2 SO2−4 + H2O + HClAll three methods can produce chlorine dioxide with high chlorite conversion yield. Unlike the other processes, the chlorite–sulfuric acid method is completely chlorine-free, although it suffers from the requirement of 25% more chlorite to produce an equivalent amount of chlorine dioxide. Alternatively, hydrogen peroxide may be efficiently used in small-scale applications.

Addition of sulfuric acid or any strong acid to chlorate salts produces chlorine dioxide.

Reduction of chlorate

In the laboratory, chlorine dioxide can also be prepared by reaction of potassium chlorate with oxalic acid:

KClO3 + H2C2O4 → 1⁄2 K2C2O4 + ClO2 + CO2 + H2Oor with oxalic and sulfuric acid:

KClO3 + 1⁄2 H2C2O4 + H2SO4 → KHSO4 + ClO2 + CO2 + H2OOver 95% of the chlorine dioxide produced in the world today is made by reduction of sodium chlorate, for use in pulp bleaching. It is produced with high efficiency in a strong acid solution with a suitable reducing agent such as methanol, hydrogen peroxide, hydrochloric acid or sulfur dioxide. Modern technologies are based on methanol or hydrogen peroxide, as these chemistries allow the best economy and do not co-produce elemental chlorine. The overall reaction can be written as:

chlorate + acid + reducing agent → chlorine dioxide + by-productsAs a typical example, the reaction of sodium chlorate with hydrochloric acid in a single reactor is believed to proceed through the following pathway:

ClO−3 + Cl + H → ClO−2 + HOCl ClO−3 + ClO−2 + 2 H → 2 ClO2 + H2O HOCl + Cl + H → Cl2 + H2Owhich gives the overall reaction

ClO−3 + Cl + 2 H → ClO2 + 1⁄2 Cl2 + H2O.The commercially more important production route uses methanol as the reducing agent and sulfuric acid for the acidity. Two advantages of not using the chloride-based processes are that there is no formation of elemental chlorine, and that sodium sulfate, a valuable chemical for the pulp mill, is a side-product. These methanol-based processes provide high efficiency and can be made very safe.

The variant process using sodium chlorate, hydrogen peroxide and sulfuric acid has been increasingly used since 1999 for water treatment and other small-scale disinfection applications, since it produce a chlorine-free product at high efficiency, over 95%.

Other processes

Very pure chlorine dioxide can also be produced by electrolysis of a chlorite solution:

NaClO2 + H2O → ClO2 + NaOH + 1⁄2 H2High-purity chlorine dioxide gas (7.7% in air or nitrogen) can be produced by the gas–solid method, which reacts dilute chlorine gas with solid sodium chlorite:

NaClO2 + 1⁄2 Cl2 → ClO2 + NaCl

Handling properties

Chlorine dioxide is very different from elemental chlorine. One of the most important qualities of chlorine dioxide is its high water solubility, especially in cold water. Chlorine dioxide does not react with water; it remains a dissolved gas in solution. Chlorine dioxide is approximately 10 times more soluble in water than elemental chlorine but its solubility is very temperature-dependent.

At partial pressures above 10 kPa (1.5 psi) (or gas-phase concentrations greater than 10% volume in air at STP) of ClO2 may explosively decompose into chlorine and oxygen. The decomposition can be initiated by light, hot spots, chemical reaction, or pressure shock. Thus, chlorine dioxide is never handled as a pure gas, but is almost always handled in an aqueous solution in concentrations between 0.5 to 10 grams per liter. Its solubility increases at lower temperatures, so it is common to use chilled water (5 °C, 41 °F) when storing at concentrations above 3 grams per liter. In many countries, such as the United States, chlorine dioxide may not be transported at any concentration and is instead almost always produced on-site. In some countries, chlorine dioxide solutions below 3 grams per liter in concentration may be transported by land, but they are relatively unstable and deteriorate quickly.

Uses

Chlorine dioxide is used for bleaching of wood pulp and for the disinfection (called chlorination) of municipal drinking water, treatment of water in oil and gas applications, disinfection in the food industry, microbiological control in cooling towers, and textile bleaching. As a disinfectant, it is effective even at low concentrations because of its unique qualities.

Bleaching

Chlorine dioxide is sometimes used for bleaching of wood pulp in combination with chlorine, but it is used alone in ECF (elemental chlorine-free) bleaching sequences. It is used at moderately acidic pH (3.5 to 6). The use of chlorine dioxide minimizes the amount of organochlorine compounds produced. Chlorine dioxide (ECF technology) currently is the most important bleaching method worldwide. About 95% of all bleached kraft pulp is made using chlorine dioxide in ECF bleaching sequences.

Chlorine dioxide has been used to bleach flour.

Water treatment

Further information: Water chlorination and Portable water purification § Chlorine dioxideThe water treatment plant at Niagara Falls, New York first used chlorine dioxide for drinking water treatment in 1944 for destroying "taste and odor producing phenolic compounds." Chlorine dioxide was introduced as a drinking water disinfectant on a large scale in 1956, when Brussels, Belgium, changed from chlorine to chlorine dioxide. Its most common use in water treatment is as a pre-oxidant prior to chlorination of drinking water to destroy natural water impurities that would otherwise produce trihalomethanes upon exposure to free chlorine. Trihalomethanes are suspected carcinogenic disinfection by-products associated with chlorination of naturally occurring organics in raw water. Chlorine dioxide also produces 70% fewer halomethanes in the presence of natural organic matter compared to when elemental chlorine or bleach is used.

Chlorine dioxide is also superior to chlorine when operating above pH 7, in the presence of ammonia and amines, and for the control of biofilms in water distribution systems. Chlorine dioxide is used in many industrial water treatment applications as a biocide, including cooling towers, process water, and food processing.

Chlorine dioxide is less corrosive than chlorine and superior for the control of Legionella bacteria. Chlorine dioxide is superior to some other secondary water disinfection methods, in that chlorine dioxide is not negatively impacted by pH, does not lose efficacy over time, because the bacteria will not grow resistant to it, and is not negatively impacted by silica and phosphates, which are commonly used potable water corrosion inhibitors. In the United States, it is an EPA-registered biocide.

It is more effective as a disinfectant than chlorine in most circumstances against waterborne pathogenic agents such as viruses, bacteria, and protozoa – including the cysts of Giardia and the oocysts of Cryptosporidium.

The use of chlorine dioxide in water treatment leads to the formation of the by-product chlorite, which is currently limited to a maximum of 1 part per million in drinking water in the USA. This EPA standard limits the use of chlorine dioxide in the US to relatively high-quality water, because this minimizes chlorite concentration, or water that is to be treated with iron-based coagulants, because iron can reduce chlorite to chloride. The World Health Organization also advises a 1ppm dosification.

Use in public crises

Chlorine dioxide has many applications as an oxidizer or disinfectant. Chlorine dioxide can be used for air disinfection and was the principal agent used in the decontamination of buildings in the United States after the 2001 anthrax attacks. After the disaster of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the surrounding Gulf Coast, chlorine dioxide was used to eradicate dangerous mold from houses inundated by the flood water.

In addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has posted a list of many disinfectants that meet its criteria for use in environmental measures against the causative coronavirus. Some are based on sodium chlorite that is activated into chlorine dioxide, though differing formulations are used in each product. Many other products on the EPA list contain sodium hypochlorite, which is similar in name but should not be confused with sodium chlorite because they have very different modes of chemical action.

Other disinfection uses

Chlorine dioxide may be used as a fumigant treatment to "sanitize" fruits such as blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries that develop molds and yeast.

Chlorine dioxide may be used to disinfect poultry by spraying or immersing it after slaughtering.

Chlorine dioxide may be used for the disinfection of endoscopes, such as under the trade name Tristel. It is also available in a trio consisting of a preceding pre-clean with surfactant and a succeeding rinse with deionized water and a low-level antioxidant.

Chlorine dioxide may be used for control of zebra and quagga mussels in water intakes.

Chlorine dioxide was shown to be effective in bedbug eradication.

For water purification during camping, disinfecting tablets containing chlorine dioxide are more effective against pathogens than those using household bleach, but typically cost more.

Other uses

Chlorine dioxide is used as an oxidant for destroying phenols in wastewater streams and for odor control in the air scrubbers of animal byproduct (rendering) plants. It is also available for use as a deodorant for cars and boats, in chlorine dioxide-generating packages that are activated by water and left in the boat or car overnight.

In dilute concentrations, chlorine dioxide is an ingredient that acts as an antiseptic agent in some mouthwashes.

Safety issues in water and supplements

Potential hazards with chlorine dioxide include poisoning and the risk of spontaneous ignition or explosion on contact with flammable materials.

Chlorine dioxide is toxic, and limits on human exposure are required to ensure its safe use. The United States Environmental Protection Agency has set a maximum level of 0.8 mg/L for chlorine dioxide in drinking water. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), an agency of the United States Department of Labor, has set an 8-hour permissible exposure limit of 0.1 ppm in air (0.3 mg/m) for people working with chlorine dioxide.

Chlorine dioxide has been fraudulently and illegally marketed as an ingestible cure for a wide range of diseases, including childhood autism and coronavirus. Children who have been given enemas of chlorine dioxide as a supposed cure for childhood autism have suffered life-threatening ailments. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has stated that ingestion or other internal use of chlorine dioxide, outside of supervised oral rinsing using dilute concentrations, has no health benefits of any kind, and it should not be used internally for any reason.

Pseudomedicine

Main article: Miracle Mineral SupplementOn 30 July and 1 October 2010, the United States Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of the product "Miracle Mineral Supplement", or "MMS", which when prepared according to the instructions produces chlorine dioxide. MMS has been marketed as a treatment for a variety of conditions, including HIV, cancer, autism, acne, and, more recently, COVID-19. Many have complained to the FDA, reporting life-threatening reactions, and even death. The FDA has warned consumers that MMS can cause serious harm to health, and stated that it has received numerous reports of nausea, diarrhea, severe vomiting, and life-threatening low blood pressure caused by dehydration. This warning was repeated for a third time on 12 August 2019, and a fourth on 8 April 2020, stating that ingesting MMS is just as hazardous as ingesting bleach, and urging consumers not to use them or give these products to their children for any reason, as there is no scientific evidence showing that chlorine dioxide has any beneficial medical properties.

References

- Haynes, William M. (2010). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (91 ed.). Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press. p. 4–58. ISBN 978-1-43982077-3.

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0116". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Dobson, Stuart; Cary, Richard; International Programme on Chemical Safety (2002). Chlorine dioxide (gas). World Health Organization. p. 4. hdl:10665/42421. ISBN 978-92-4-153037-8. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- "Chlorine dioxide". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 845. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- "mp-23207: ClO2 (Orthorhombic, Pbca, 61)". Materials Project. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- Brockway, L. O. (March 1933). "The Three-Electron Bond in Chlorine Dioxide" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 19 (3): 303–307. Bibcode:1933PNAS...19..303B. doi:10.1073/pnas.19.3.303. PMC 1085967. PMID 16577512.

- ^ Linus Pauling (1988). General chemistry. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 264. ISBN 0-486-65622-5.

- Flesch, R.; Plenge, J.; Rühl, E. (2006). "Core-level excitation and fragmentation of chlorine dioxide". International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 249–250: 68–76. Bibcode:2006IJMSp.249...68F. doi:10.1016/j.ijms.2005.12.046.

- Aieta, E. Marco, and James D. Berg. "A Review of Chlorine Dioxide in Drinking Water Treatment." Journal (American Water Works Association) 78, no. 6 (1986): 62-72. Accessed April 24, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41273622

- Porter, George; Wright, Franklin J. (1953). "Studies of free radical reactivity by the methods of flash photolysis. The photochemical reaction between chlorine and oxygen". Discussions of the Faraday Society. 14: 23. doi:10.1039/df9531400023. ISSN 0366-9033.

- Derby, R. I.; Hutchinson, W. S. (1953). "Chlorine(IV) Oxide". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 4. pp. 152–158. doi:10.1002/9780470132357.ch51. ISBN 978-0-470-13235-7.

- ^ Vogt, H.; Balej, J.; Bennett, J. E.; Wintzer, P.; Sheikh, S. A.; Gallone, P.; Vasudevan, S.; Pelin, K. (2010). "Chlorine Oxides and Chlorine Oxygen Acids". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_483.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Ni, Y.; Wang, X. (1996). "Mechanism of the Methanol Based ClO2 Generation Process". International Pulp Bleaching Conference. TAPPI. pp. 454–462.

- ^ White, George W.; White, Geo Clifford (1999). The handbook of chlorination and alternative disinfectants (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley. ISBN 0-471-29207-9.

- Swaddle, Thomas Wilson (1997). Inorganic Chemistry: An Industrial and Environmental Perspective. Academic Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 0-12-678550-3.

- ^ Alternative Disinfectants and Oxidants Manual, chapter 4: Chlorine Dioxide (PDF), US Environmental Protection Agency: Office of Water, April 1999, archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2015, retrieved November 27, 2009

- ^ Block, Seymour Stanton (2001). Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation (5th ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. p. 215. ISBN 0-683-30740-1.

- ^ Simpson, Gregory Deward (2005). Practical Chlorine Dioxide (Volume 1 ed.). Colleyville, Texas: Greg D. Simpson & Associates. ISBN 0-9771985-0-2.

- Sjöström, E. (1993). Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-647480-X. OCLC 58509724.

- "AET – Reports – Science – Trends in World Bleached Chemical Pulp Production: 1990–2005". Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- Harrel, C. G. (1952). "Maturing and Bleaching Agents in Producing Flour". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 44 (1): 95–100. doi:10.1021/ie50505a030.

- Sorlini, S.; Collivignarelli, C. (2005). "Trihalomethane formation during chemical oxidation with chlorine, chlorine dioxide and ozone of ten Italian natural waters". Desalination. 176 (1–3): 103–111. Bibcode:2005Desal.176..103S. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2004.10.022.

- Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Gao, M. (1996). "A pilot study on trihalomethane formation in water treated by chlorine dioxide". Zhonghua Yufang Yixue Zazhi (Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine) (in Chinese). 30 (1): 10–13. PMID 8758861.

- ^ Volk, C. J.; Hofmann, R.; Chauret, C.; Gagnon, G. A.; Ranger, G.; Andrews, R. C. (2002). "Implementation of chlorine dioxide disinfection: Effects of the treatment change on drinking water quality in a full-scale distribution system". Journal of Environmental Engineering and Science. 1 (5): 323–330. Bibcode:2002JEES....1..323V. doi:10.1139/s02-026.

- Pereira, M. A.; Lin, L. H.; Lippitt, J. M.; Herren, S. L. (1982). "Trihalomethanes as initiators and promoters of carcinogenesis". Environmental Health Perspectives. 46: 151–156. doi:10.2307/3429432. JSTOR 3429432. PMC 1569022. PMID 7151756.

- ^ "Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edition, incorporating the 1st addendum". World Health Organization. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- "Chlorine dioxide as a disinfectant". Lenntech. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- Andrews, L.; Key, A.; Martin, R.; Grodner, R.; Park, D. (2002). "Chlorine dioxide wash of shrimp and crawfish an alternative to aqueous chlorine". Food Microbiology. 19 (4): 261–267. doi:10.1006/fmic.2002.0493.