This is an old revision of this page, as edited by PAR (talk | contribs) at 17:22, 11 November 2021. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:22, 11 November 2021 by PAR (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Medication for parasite infestationsPharmaceutical compound

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Stromectol, Soolantra, Sklice, others |

| Other names | MK-933 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | |

| MedlinePlus | a607069 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | – |

| Protein binding | 93% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP450) |

| Elimination half-life | 18 hours |

| Excretion | Feces; <1% urine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.067.738 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

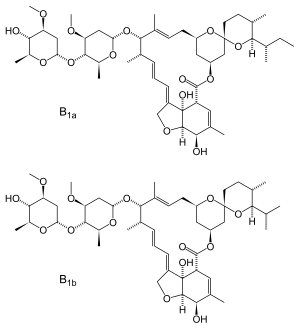

| Formula | C 48H 74O 14 (22,23-dihydroavermectin B1a) C 47H 72O 14 (22,23-dihydroavermectin B1b) |

| Molar mass |

|

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Ivermectin is a medication used to treat parasite infestations. In humans, these include head lice, scabies, river blindness (onchocerciasis), strongyloidiasis, trichuriasis, ascariasis, and lymphatic filariasis. In veterinary medicine, the medication is used to prevent and treat heartworm and acariasis, among other indications. Ivermectin works through many mechanisms of action that result in the death of the targeted parasites; it can be taken by mouth or applied to the skin for external infestations. The drug belongs to the avermectin family of medications.

Ivermectin was discovered in 1975 and came into medical use in 1981; William Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura won the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for its discovery and applications. The medication is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, and is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an antiparasitic agent. In 2018, ivermectin was the 420th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one hundred thousand prescriptions. It is available as a generic medicine.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, unfounded claims were widely spread that ivermectin is beneficial for treating and preventing COVID-19. At the time, such claims were not backed by credible scientific evidence. Further research has confirmed the ability of ivermectin to bind to the COVID-2 spike protein, indicating that it may be beneficial in the treatment of the disease. Clinical trials are ongoing, but at the present time, multiple major health organizations, including the Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the European Medicines Agency, and the World Health Organization have stated that ivermectin is not authorized or approved to treat COVID-19.

Medical uses

Ivermectin is used to treat human diseases caused by roundworms and ectoparasites.

Worm infections

For river blindness (onchocerciasis) and lymphatic filariasis, ivermectin is typically given as part of mass drug administration campaigns that distribute the drug to all members of a community affected by the disease. For river blindness, a single oral dose of ivermectin (150 micrograms per kilogram of body weight) clears the body of larval Onchocerca volvulus worms for several months, preventing transmission and disease progression. Adult worms survive in the skin and eventually recover to produce larval worms again; to keep the worms at bay, ivermectin is given at least once per year for the 10–15-year lifespan of the adult worms. For lymphatic filariasis, oral ivermectin (200 micrograms per kilogram body weight) is part of a combination treatment given annually: ivermectin, diethylcarbamazine citrate and albendazole in places without onchocerciasis; and ivermectin and albendazole in places with onchocerciasis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers ivermectin the drug of choice for strongyloidiasis. Most cases are treated with two daily doses of oral ivermectin (200 μg per kg body weight), while severe infections are treated with five to seven days of ivermectin. Ivermectin is also the primary treatment for Mansonella ozzardi and cutaneous larva migrans. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends ivermectin, albendazole, or mebendazole as treatments for ascariasis. Ivermectin is sometimes added to albendazole or mebendazole for whipworm treatment, and is considered a second-line treatment for gnathostomiasis.

Mites and insects

Ivermectin is also used to treat infection with parasitic arthropods. Scabies – infestation with the mite Sarcoptes scabiei – is most commonly treated with topical permethrin or oral ivermectin. For most scabies cases, ivermectin is used in a two dose regimen: a first dose kills the active mites, but not their eggs. Over the next week, the eggs hatch, and a second dose kills the newly hatched mites. For severe "crusted scabies", the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends up to seven doses of ivermectin over the course of a month, along with a topical antiparasitic. Both head lice and pubic lice can be treated with oral ivermectin, an ivermectin lotion applied directly to the affected area, or various other insecticides. Ivermectin is also used to treat rosacea and blepharitis, both of which can be caused or exacerbated by Demodex folliculorum mites.

Contraindications

Ivermectin is contraindicated in children under the age of five or those who weigh less than 15 kilograms (33 pounds), and individuals with liver or kidney disease. The medication is secreted in very low concentration in breast milk. It remains unclear if ivermectin is safe during pregnancy.

Adverse effects

Side effects, although uncommon, include fever, itching, and skin rash when taken by mouth; and red eyes, dry skin, and burning skin when used topically for head lice. It is unclear if the drug is safe for use during pregnancy, but it is probably acceptable for use during breastfeeding.

Ivermectin is considered relatively free of toxicity in standard doses (around 300 µg/kg). Based on the data drug safety sheet for ivermectin, side effects are uncommon. However, serious adverse events following ivermectin treatment are more common in people with very high burdens of larval Loa loa worms in their blood. Those who have over 30,000 microfilaria per milliliter of blood risk inflammation and capillary blockage due to the rapid death of the microfilaria following ivermectin treatment.

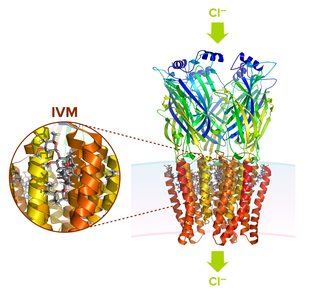

One concern is neurotoxicity after large overdoses, which in most mammalian species may manifest as central nervous system depression, ataxia, coma, and even death, as might be expected from potentiation of inhibitory chloride channels.

Since drugs that inhibit the enzyme CYP3A4 often also inhibit P-glycoprotein transport, the risk of increased absorption past the blood-brain barrier exists when ivermectin is administered along with other CYP3A4 inhibitors. These drugs include statins, HIV protease inhibitors, many calcium channel blockers, lidocaine, the benzodiazepines, and glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone.

During the course of a typical treatment, ivermectin can cause minor aminotransferase elevations. In rare cases it can cause mild clinically apparent liver disease.

To provide context for the dosing and toxicity ranges, the LD50 of ivermectin in mice is 25 mg/kg (oral), and 80 mg/kg in dogs, corresponding to an approximated human-equivalent dose LD50 range of 2.02-43.24 mg/kg, which is far in excess of its FDA-approved usage (a single dose of 0.150-0.200 mg/kg to be used for specific parasitic infections). While ivermectin has also been studied for use in COVID-19, and while it has some ability to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro, achieving 50% inhibition in vitro was found to require an estimated oral dose of 7.0 mg/kg (or 35x the maximum FDA-approved dosage), high enough to be considered ivermectin poisoning. Despite insufficient data to show any safe and effective dosing regimen for ivermectin in COVID-19, doses have been taken far in excess of FDA-approved dosing, leading the CDC to issue a warning of overdose symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, decreased level of consciousness, confusion, blurred vision, visual hallucinations, loss of coordination and balance, seizures, coma, and death. The CDC advises against consuming doses intended for livestock or doses intended for external use and warns that increasing misuse of ivermectin-containing products is resulting in an increasing rate of harmful overdoses.

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Ivermectin and its related drugs act by interfering with the nerve and muscle functions of helminths and insects. The drug binds to glutamate-gated chloride channels common to invertebrate nerve and muscle cells. The binding pushes the channels open, which increases the flow of chloride ions and hyper-polarizes the cell membranes, paralyzing and killing the invertebrate. Ivermectin is safe for mammals (at the normal therapeutic doses used to cure parasite infections) because mammalian glutamate-gated chloride channels only occur in the brain and spinal cord: the causative avermectins usually do not cross the blood–brain barrier, and are unlikely to bind to other mammalian ligand-gated channels.

Pharmacokinetics

Ivermectin can be given by mouth, topically, or via injection. It does not readily cross the blood–brain barrier of mammals due to the presence of P-glycoprotein (the MDR1 gene mutation affects the function of this protein). Crossing may still become significant if ivermectin is given at high doses, in which case brain levels peak 2–5 hours after administration. In contrast to mammals, ivermectin can cross the blood–brain barrier in tortoises, often with fatal consequences.

Chemistry

Fermentation of Streptomyces avermitilis yields eight closely related avermectin homologues, of which B1a and B1b form the bulk of the products isolated. In a separate chemical step, the mixture is hydrogenated to give ivermectin, which is an approximately 80:20 mixture of the two 22,23-dihydroavermectin compounds.

Ivermectin is a macrocyclical lactone.

History

The avermectin family of compounds was discovered by Satoshi Ōmura of Kitasato University and William Campbell of Merck. In 1970, Ōmura isolated unusual Streptomyces bacteria from the soil near a golf course along the south east coast of Honshu, Japan. Ōmura sent the bacteria to William Campbell, who showed that the bacterial culture could cure mice infected with the roundworm Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Campbell isolated the active compounds from the bacterial culture, naming them "avermectins" and the bacterium Streptomyces avermitilis for the compounds' ability to clear mice of worms (in Latin: a 'without', vermis 'worms'). Of the various avermectins, Campbell's group found the compound "avermectin B1" to be the most potent when taken orally. They synthesized modified forms of avermectin B1 to improve its pharmaceutical properties, eventually choosing a mixture of at least 80% 22,23-dihydroavermectin B1a and up to 20% 22,23-dihydroavermectin B1b, a combination they called "ivermectin".

The discovery of ivermectin has been described as a combination of "chance and choice." Merck was looking for a broad-spectrum anthelmintic, which ivermectin is indeed; however, Campbell noted that they "...also found a broad-spectrum agent for the control of ectoparasitic insects and mites."

Merck began marketing ivermectin as a veterinary antiparasitic in 1981. By 1986, ivermectin was registered for use in 46 countries and was administered massively to cattle, sheep and other animals. By the late 1980s, ivermectin was the bestselling veterinary medicine in the world. Following its blockbuster success as a veterinary antiparasitic, another Merck scientist, Mohamed Aziz, collaborated with the World Health Organization to test the safety and efficacy of ivermectin against onchocerciasis in humans. They found it to be highly safe and effective, triggering Merck to register ivermectin for human use as "Mectizan" in France in 1987. A year later, Merck CEO Roy Vagelos agreed that Merck would donate all ivermectin needed to eradicate river blindness. In 1998, that donation would be expanded to include ivermectin used to treat lymphatic filariasis.

Ivermectin earned the title of "wonder drug" for the treatment of nematodes and arthropod parasites. Ivermectin has been used safely by hundreds of millions of people to treat river blindness and lymphatic filariasis.

Half of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Campbell and Ōmura for discovering avermectin, "the derivatives of which have radically lowered the incidence of river blindness and lymphatic filariasis, as well as showing efficacy against an expanding number of other parasitic diseases".

Society and culture

Economics

The initial price proposed by Merck in 1987 was US$6 per treatment, which was unaffordable for patients who most needed ivermectin. The company donated hundreds of millions of courses of treatments since 1988 in more than 30 countries. Between 1995 and 2010, the program using donated ivermectin to prevent river blindness is estimated to have prevented seven million years of disability at a cost of US$257 million.

Ivermectin is considered an inexpensive drug. As of 2019, ivermectin tablets (Stromectol) in the United States were the least expensive treatment option for lice in children at approximately US$9.30, while Sklice, an ivermectin lotion, cost around US$300 for 4 US fl oz (120 ml).

As of 2019, the cost effectiveness of treating scabies and lice with ivermectin has not been studied.

Brand names

It is sold under the brand names Heartgard, Sklice and Stromectol in the United States, Ivomec worldwide by Merial Animal Health, Mectizan in Canada by Merck, Iver-DT in Nepal by Alive Pharmaceutical and Ivexterm in Mexico by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International. In Southeast Asian countries, it is marketed by Delta Pharma Ltd. under the trade name Scabo 6. The formulation for rosacea treatment is sold under the brand name Soolantra. While in development, it was assigned the code MK-933 by Merck.

COVID-19 misinformation

Further information: COVID-19 misinformation § IvermectinIvermectin has been pushed by right-wing politicians and activists promoting it as a supposed COVID treatment. Misinformation about ivermectin's efficacy spread widely on social media, fueled by publications that have since been retracted, misleading "meta-analysis" websites with substandard methods, and conspiracy theories about efforts by governments and scientists to "suppress the evidence."

In response to widespread misuse, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Centers for Disease Control, World Health Organization, American Medical Association, American Pharmacists Association, and American Society of Health-System Pharmacists issued statements in 2021 warning that ivermectin is not approved or authorized for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19, and advised against its use for that purpose outside of clinical trials.

On September 1, 2021, health experts from the United States expressed concerns from reports of sharp increases in outpatient prescribing and dispensing of ivermectin with respect to levels before the pandemic. These experts explain that the CDC has not authorized or approved ivermectin for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19. The American Association of Poison Control Centers has reported 1,440 cases of ivermectin poisoning through September 20, 2021, a three-fold increase compared to similar time periods in 2019 and 2020.

Research

COVID-19

This section is an excerpt from COVID-19 drug repurposing research § Ivermectin. Template loop detected: Template:ExcerptTropical diseases

Ivermectin is being studied as a potential antiviral agent against chikungunya and yellow fever. In chikungunya, ivermectin had a wide in vitro safety margin as an antiviral.

Ivermectin is also of interest in the prevention of malaria, as it is toxic to both the malaria plasmodium itself and the mosquitos that carry it. A direct effect on malaria parasites could not be shown in an experimental infection of volunteers with Plasmodium falciparum. Use of ivermectin at higher doses necessary to control malaria is probably safe, though large clinical trials have not yet been done to definitively establish the efficacy or safety of ivermectin for prophylaxis or treatment of malaria. Mass drug administration of a population with ivermectin to treat and prevent nematode infestation is effective for eliminating malaria-bearing mosquitos and thereby reducing infection with residual malaria parasites.

One alternative to ivermectin is moxidectin, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in people with river blindness. Moxidectin has a longer half-life than ivermectin and may eventually supplant ivermectin as it is a more potent microfilaricide, but there is a need for additional clinical trials, with long-term follow-up, to assess whether moxidectin is safe and effective for treatment of nematode infection in children and women of childbearing potential.

There is tentative evidence that ivermectin kills bedbugs, as part of integrated pest management for bedbug infestations. However, such use may require a prolonged course of treatment which is of unclear safety.

NAFLD

In 2013, ivermectin was demonstrated as a novel ligand of the farnesoid X receptor, a therapeutic target for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Veterinary use

Ivermectin is routinely used to control parasitic worms in the gastrointestinal tract of ruminant animals. These parasites normally enter the animal when it is grazing, pass the bowel, and set and mature in the intestines, after which they produce eggs that leave the animal via its droppings and can infest new pastures. Ivermectin is only effective in killing some of these parasites, this is because of an increase in anthelmintic resistance. This resistance has arisen from the persistent use of the same anthelmintic drugs for the past 40 years.

In dogs, ivermectin is routinely used as prophylaxis against heartworm. Dogs with defects in the P-glycoprotein gene (MDR1), often collie-like herding dogs, can be severely poisoned by ivermectin. The mnemonic "white feet, don't treat" refers to Scotch collies that are vulnerable to ivermectin. Some other dog breeds (especially the Rough Collie, the Smooth Collie, the Shetland Sheepdog, and the Australian Shepherd), also have a high incidence of mutation within the MDR1 gene (coding for P-glycoprotein) and are sensitive to the toxic effects of ivermectin. Clinical evidence suggests kittens are susceptible to ivermectin toxicity. A 0.01% ivermectin topical preparation for treating ear mites in cats is available.

Ivermectin is sometimes used as an acaricide in reptiles, both by injection and as a diluted spray. While this works well in some cases, care must be taken, as several species of reptiles are very sensitive to ivermectin. Use in turtles is particularly contraindicated.

A characteristic of the antinematodal action of ivermectin is its potency: for instance, to combat Dirofilaria immitis in dogs, ivermectin is effective at 0.001 milligram per kilogram of body weight when administered orally.

For dogs, the insecticide spinosad may have the effect of increasing the toxicity of ivermectin.

See also

Notes

- In people with onchocerciasis, diethylcarbamazine citrate can cause a dangerous set of side effects called Mazzotti reaction. Due to this, diethylcarbamazine citrate is avoided in places where onchocerciasis is common.

- This recommendation is not universal. The World Health Organization recommends ascariasis be treated with mebendazole or pyrantel pamoate, while the textbook Parasitic Diseases recommends albendazole or mebendazole. A 2020 Cochrane review concluded that the three drugs are equally safe and effective for treating ascariasis.

- New Drug Application Identifier: 50-742/S-022

References

- ^ "Stromectol – ivermectin tablet". DailyMed. December 15, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ "Soolantra – ivermectin cream". DailyMed. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- "FDA Approves Lotion for Nonprescription Use to Treat Head Lice". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). October 27, 2020. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Package Labeling" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 8, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- "List of nationally authorised medicinal products" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. November 26, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Ivermectin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ Laing R, Gillan V, Devaney E (June 2017). "Ivermectin – Old Drug, New Tricks?". Trends in Parasitology. 33 (6): 463–72. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2017.02.004. PMC 5446326. PMID 28285851.

- Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery a History. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0.

- ^ Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs: Small and Large Animal (4 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2015. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-323-24486-2. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (August 23, 2019). "Ascariasis – Resources for Health Professionals". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Panahi Y, Poursaleh Z, Goldust M (2015). "The efficacy of topical and oral ivermectin in the treatment of human scabies" (PDF). Annals of Parasitology. 61 (1): 11–16. PMID 25911032. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2020.

- Mehlhorn H (2008). Encyclopedia of parasitology (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 646. ISBN 978-3-540-48994-8. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020.

- Vercruysse J, Rew RS, eds. (2002). Macrocyclic lactones in antiparasitic therapy. Oxon, UK: CABI Pub. p. Preface. ISBN 978-0-85199-840-4. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2015" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Ahmed S, Karim MM, Ross AG, Hossain MS, Clemens JD, Sumiya MK, et al. (December 2020). "A five-day course of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 may reduce the duration of illness". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 103: 214–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.191. PMC 7709596. PMID 33278625.

- "Ivermectin – Drug Usage Statistics, ClinCalc DrugStats Database". clincalc.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- "Ivermectin: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- "Ivermectin lotion: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- Evershed N, McGowan M, Ball A. "Anatomy of a conspiracy theory: how misinformation travels on Facebook". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- "Fact-checking claim about the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19". PolitiFact. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "EMA advises against use of ivermectin for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 outside randomised clinical trials". European Medicines Agency. March 22, 2021. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Garegnani LI, Madrid E, Meza N (April 22, 2021). "Misleading clinical evidence and systematic reviews on ivermectin for COVID-19". BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111678. ISSN 2515-446X. PMID 33888547. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Lehrer, Steven; Rheinstein, Peter H. (September–October 2020). "Ivermectin Docks to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-binding Domain Attached to ACE2". In Vivo. 34 (5). doi:10.21873/invivo.12134. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- Saha, J.; Raihan, M. (2021). "The binding mechanism of ivermectin and levosalbutamol with spike protein of SARS-CoV-2". Structural Chemistry. doi:10.1007/s11224-021-01776-0. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- Eweas, A.; Alhossary, A.; Abdel-Moneim, A. (25 Jan, 2021). "Molecular docking reveals ivermectin and remdesivir as potential repurposed drugs against SARS-CoV-2". Front. Microbiol. 11:592908. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.592908. Retrieved Nov 11, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ashour DS (August 2019). "Ivermectin: From theory to clinical application". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 54 (2): 134–42. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.05.003. PMID 31071469. S2CID 149445017.

- "Onchocerciasis". World Health Organization. June 14, 2019. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- "Lymphatic filariasis". World Health Organization. March 2, 2020. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- Babalola OE (2011). "Ocular onchocerciasis: current management and future prospects". Clin Ophthalmol. 5: 1479–91. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S8372. PMC 3206119. PMID 22069350.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - "Strongyloidiasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "26. Other Nematodes of Medical Imortance". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 294. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "27. Aberrant Nematode Infections". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 299. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Ascariasis – Resources for Health Professionals". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). May 20, 2020. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- "Water related diseases – Ascariasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "18. Ascaris lumbricoides". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 211. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Conterno LO, Turchi MD, Corrêa I, Monteiro de Barros Almeida RA (April 2020). "Anthelmintic drugs for treating ascariasis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4: CD010599. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010599.pub2. PMC 7156140. PMID 32289194.

- Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "17. Trichuris trichiura". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 201. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, Chosidow O, Chang AY (March 2020). "Ectoparasites: Scabies". J Am Acad Dermatol. 82 (3): 533–48. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109. PMID 31310840.

- ^ "Scabies – Medications". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). October 2, 2019. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- Gunning K, Kiraly B, Pippitt K (May 2019). "Lice and Scabies: Treatment Update". Am Fam Physician. 99 (10): 635–42. PMID 31083883.

- "Pubic "Crab" Lice – Treatment". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). September 12, 2019. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- vaan Zuuren EJ (November 2017). "Rosacea". N Engl J Med. 377 (18): 1754–64. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1506630. PMID 29091565.

- Elston CA, Elston DM (2014). "Demodex mites". Clin Dermatol. 32 (6): 739–43. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.02.012. PMID 25441466.

- Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA (December 2005). "Ivermectin: pharmacology and application in dermatology". International Journal of Dermatology. 44 (12): 981–88. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02253.x. PMID 16409259. S2CID 27019223. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Heukelbach J, Winter B, Wilcke T, Muehlen M, Albrecht S, de Oliveira FA, Kerr-Pontes LR, Liesenfeld O, Feldmeier H (August 2004). "Selective mass treatment with ivermectin to control intestinal helminthiases and parasitic skin diseases in a severely affected population". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82 (8): 563–71. PMC 2622929. PMID 15375445. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018.

- Koh YP, Tian EA, Oon HH (September 2019). "New changes in pregnancy and lactation labelling: Review of dermatologic drugs". Int J Womens Dermatol. 5 (4): 216–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.05.002. PMC 6831768. PMID 31700976.

- Nicolas P, Maia MF, Bassat Q, Kobylinski KC, Monteiro W, Rabinovich NR, Menéndez C, Bardají A, Chaccour C (January 2020). "Safety of oral ivermectin during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet Glob Health. 8 (1): e92 – e100. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30453-X. PMID 31839144.

- "Ivermectin (topical)". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. July 27, 2020. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- "Ivermectin Levels and Effects while Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Navarro M, Camprubí D, Requena-Méndez A, Buonfrate D, Giorli G, Kamgno J, et al. (April 2020). "Safety of high-dose ivermectin: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 75 (4): 827–834. doi:10.1093/jac/dkz524. PMID 31960060.

- Martin RJ, Robertson AP, Choudhary S (January 2021). "Ivermectin: An Anthelmintic, an Insecticide, and Much More". Trends in Parasitology. 37 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2020.10.005. PMC 7853155. PMID 33189582.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC embargo expired (link) - ^ Pion SD, Tchatchueng-Mbougua JB, Chesnais CB, Kamgno J, Gardon J, Chippaux JP, et al. (April 2019). "Effect of a Single Standard Dose (150–200 μg/kg) of Ivermectin on Loa loa Microfilaremia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 6 (4): ofz019. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz019. PMC 6449757. PMID 30968052.

- Martin RJ, Robertson AP, Choudhary S (January 2021). "Ivermectin: An Anthelmintic, an Insecticide, and Much More". Trends in Parasitology. 37 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2020.10.005. PMC 7853155. PMID 33189582.

Although relatively free from toxicity, ivermectin – when large overdoses are administered – may cross the blood–brain barrier, producing depressant effects on the CNS

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC embargo expired (link) - Campillo JT, Boussinesq M, Bertout S, Faillie JL, Chesnais CB (April 2021). "Serious adverse reactions associated with ivermectin: A systematic pharmacovigilance study in sub-Saharan Africa and in the rest of the World". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 15 (4): e0009354. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009354. PMC 8087035. PMID 33878105.

Few hours after administration: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, salivation, tachycardia, hypotension, ataxia, pyramidal signs, binocular diplopia

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Office of the Commissioner (March 12, 2021). "Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

You can also overdose on ivermectin, which can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension (low blood pressure), allergic reactions (itching and hives), dizziness, ataxia (problems with balance), seizures, coma and even death.

- El-Saber Batiha G, Alqahtani A, Ilesanmi OB, Saati AA, El-Mleeh A, Hetta HF, Magdy Beshbishy A (August 2020). "Avermectin Derivatives, Pharmacokinetics, Therapeutic and Toxic Dosages, Mechanism of Action, and Their Biological Effects". Pharmaceuticals. 13 (8): 196. doi:10.3390/ph13080196. PMC 7464486. PMID 32824399.

Based on the reported neurotoxicity and metabolic pathway of IVM, caution should be taken to conduct clinical trial on its antiviral potentials. The GABA-gated chloride channels in the human nervous system might be a target for IVM, this is because the BBB in disease-patient might be a weakened as a result of inflammation and other destructive processes, allowing IVM to cross the BBB and gain access to the CNS where it can elicit its neurotoxic effect

- Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Paker KL (2006). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1084–87. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2. OCLC 1037399847.

- Ivermectin. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. PMID 31644227. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Juarez M, Schcolnik-Cabrera A, Dueñas-Gonzalez A (2018). "The multitargeted drug ivermectin: from an antiparasitic agent to a repositioned cancer drug". American Journal of Cancer Research. 8 (2): 317–331. PMC 5835698. PMID 29511601.

- "STROMECTOL® (IVERMECTIN) Drug Monograph" (PDF). FDA.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- Schmith VD, Zhou JJ, Lohmer LR (October 2020). "The Approved Dose of Ivermectin Alone is not the Ideal Dose for the Treatment of COVID-19". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 108 (4): 762–765. doi:10.1002/cpt.1889. PMID 32378737.

- ^ "Rapid Increase in Ivermectin Prescriptions and Reports of Severe Illness Associated with Use of Products Containing Ivermectin to Prevent or Treat COVID-19". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Alert Network. August 26, 2021. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Martin RJ, Robertson AP, Choudhary S (January 2021). "Ivermectin: An Anthelmintic, an Insecticide, and Much More". Trends Parasitol. 37 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2020.10.005. PMC 7853155. PMID 33189582. S2CID 226972704.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC embargo expired (link) - ^ Omura S, Crump A (September 2014). "Ivermectin: panacea for resource-poor communities?". Trends Parasitol. 30 (9): 445–55. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2014.07.005. PMID 25130507.

- Borst P, Schinkel AH (June 1996). "What have we learnt thus far from mice with disrupted P-glycoprotein genes?". European Journal of Cancer. 32A (6): 985–90. doi:10.1016/0959-8049(96)00063-9. PMID 8763339.

- Teare JA, Bush M (December 1983). "Toxicity and efficacy of ivermectin in chelonians" (PDF). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 183 (11): 1195–7. PMID 6689009. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- Lasota JA, Dybas RA (1991). "Avermectins, a novel class of compounds: implications for use in arthropod pest control". Annual Review of Entomology. 36: 91–117. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.36.010191.000515. PMID 2006872.

- Jansson RK, Dybas RA (1998). "Avermectins: Biochemical Mode of Action, Biological Activity and Agricultural Importance". Insecticides with Novel Modes of Action. Applied Agriculture. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 152–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-03565-8_9. ISBN 978-3-642-08314-3.

- Campbell WC (July 1985). "Ivermectin: an update". Parasitology Today. 1 (1): 10–6. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(85)90100-0. PMID 15275618.

- ^ Campbell WC, Fisher MH, Stapley EO, Albers-Schönberg G, Jacob TA (August 1983). "Ivermectin: a potent new antiparasitic agent". Science. 221 (4613): 823–28. Bibcode:1983Sci...221..823C. doi:10.1126/science.6308762. PMID 6308762.

- Campbell WC (January 1, 2005). "Serendipity and new drugs for infectious disease". ILAR Journal. 46 (4): 352–356. doi:10.1093/ilar.46.4.352. PMID 16179743.

- Omura S, Crump A (December 2004). "The life and times of ivermectin - a success story". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 2 (12): 984–9. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1048. PMID 15550944. S2CID 22722403.

- ^ Molyneux DH, Ward SA (December 2015). "Reflections on the Nobel Prize for Medicine 2015--The Public Health Legacy and Impact of Avermectin and Artemisinin". Trends in Parasitology. 31 (12): 605–607. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2015.10.008. PMID 26552892.

- Crump A, Morel CM, Omura S (July 2012). "The onchocerciasis chronicle: from the beginning to the end?". Trends in Parasitology. 28 (7): 280–8. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.04.005. PMID 22633470.

- Geary TG (November 2005). "Ivermectin 20 years on: maturation of a wonder drug". Trends in Parasitology. 21 (11): 530–32. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.014. PMID 16126457.

- ^ Crump A, Ōmura S (2011). "Ivermectin, 'wonder drug' from Japan: the human use perspective". Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and Biological Sciences. 87 (2): 13–28. Bibcode:2011PJAB...87...13C. doi:10.2183/pjab.87.13. PMC 3043740. PMID 21321478.

- Omaswa F, Crisp N (2014). African Health Leaders: Making Change and Claiming the Future. OUP Oxford. p. PT158. ISBN 978-0191008412.

- Arévalo AP, Pagotto R, Pórfido JL, Daghero H, Segovia M, Yamasaki K, et al. (March 2021). "Ivermectin reduces in vivo coronavirus infection in a mouse experimental model". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 7132. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.7132A. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86679-0. PMC 8010049. PMID 33785846.

- Kliegman RM, St Geme J (2019). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 3575. ISBN 978-0323568883.

- Chiu S, Argaez C (2019). Ivermectin for Parasitic Skin Infections of Scabies: A Review of Comparative Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Guidelines. CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. PMID 31424718. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Young C, Argáez C (2019). Ivermectin for Parasitic Skin Infections of Lice: A Review of Comparative Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Guidelines. CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. PMID 31487135. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- "Sklice – ivermectin lotion". DailyMed. November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- Adhikari S (May 27, 2014). "Alive Pharmaceutical (P) LTD.: Iver-DT". Alive Pharmaceutical (P) LTD. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- Pampiglione S, Majori G, Petrangeli G, Romi R (1985). "Avermectins, MK-933 and MK-936, for mosquito control". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 79 (6): 797–99. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(85)90121-X. PMID 3832491.

- Davey M (July 15, 2021). "Huge study supporting ivermectin as Covid treatment withdrawn over ethical concerns". The Guardian.

- Darcy O. "Right-wing media pushed a deworming drug to treat Covid-19 that the FDA says is unsafe for humans". CNN. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- Blake A (August 24, 2021). "How the right's ivermectin conspiracy theories led to people buying horse dewormer". Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- "Surgisphere Sows Confusion About Another Unproven COVID-19 Drug". The Scientist Magazine®. June 16, 2020. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- Piller C, Servick K (June 4, 2020). "Two elite medical journals retract coronavirus papers over data integrity questions". Science. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- Garegnani LI, Madrid E, Meza N (April 2021). "Misleading clinical evidence and systematic reviews on ivermectin for COVID-19". BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111678. PMID 33888547.

- Molento MB (December 2021). "Ivermectin against COVID-19: The unprecedented consequences in Latin America". One Health. 13: 100250. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100250. PMC 8050401. PMID 33880395.

- Dupuy B (December 11, 2020). "No evidence ivermectin is a miracle drug against COVID-19" (Fact check). AP News. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Sharma R (February 24, 2021). "What is Ivermectin? Why social media creates Covid 'miracle drugs' – and why you shouldn't trust the crowd". inews.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- "AMA, APhA, ASHP statement on ending use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19". American Medical Association. September 1, 2021. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- Lukpat A, Goldberg E (September 4, 2021). "Health experts keep warning against using ivermectin as a Covid treatment. Some Americans refuse to listen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Lukpat A (September 25, 2021). "New Mexico health officials link misuse of ivermectin to two Covid-19 deaths". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Varghese FS, Kaukinen P, Gläsker S, Bespalov M, Hanski L, Wennerberg K, et al. (February 2016). "Discovery of berberine, abamectin and ivermectin as antivirals against chikungunya and other alphaviruses". Antiviral Research. 126: 117–24. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.12.012. PMID 26752081.

- Kinobe RT, Owens L (April 2021). "A systematic review of experimental evidence for antiviral effects of ivermectin and an in silico analysis of ivermectin's possible mode of action against SARS-CoV-2". Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 35 (2): 260–76. doi:10.1111/fcp.12644. PMC 8013482. PMID 33427370.

- Chaccour C, Hammann F, Rabinovich NR (April 2017). "Ivermectin to reduce malaria transmission I. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations regarding efficacy and safety". Malaria Journal. 16 (1): 161. doi:10.1186/s12936-017-1801-4. PMC 5402169. PMID 28434401.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Siewe Fodjo JN, Kugler M, Hotterbeekx A, Hendy A, Van Geertruyden JP, Colebunders R (August 2019). "Would ivermectin for malaria control be beneficial in onchocerciasis-endemic regions?". Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 8 (1): 77. doi:10.1186/s40249-019-0588-7. PMC 6706915. PMID 31439040.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Fontinha D, Moules I, Prudêncio M (July 2020). "Repurposing Drugs to Fight Hepatic Malaria Parasites". Molecules. 25 (15): 3409. doi:10.3390/molecules25153409. PMC 7435416. PMID 32731386.

- Navarro M, Camprubí D, Requena-Méndez A, Buonfrate D, Giorli G, Kamgno J, Gardon J, Boussinesq M, Muñoz J, Krolewiecki A (April 2020). "Safety of high-dose ivermectin: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75 (4): 827–34. doi:10.1093/jac/dkz524. PMID 31960060.

- Tizifa TA, Kabaghe AN, McCann RS, van den Berg H, Van Vugt M, Phiri KS (2018). "Prevention Efforts for Malaria". Curr Trop Med Rep. 5 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1007/s40475-018-0133-y. PMC 5879044. PMID 29629252.

- Maheu-Giroux M, Joseph SA (August 2018). "Moxidectin for deworming: from trials to implementation". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 18 (8): 817–19. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30270-6. PMID 29858152.

- Boussinesq M (October 2018). "A new powerful drug to combat river blindness". Lancet. 392 (10154): 1170–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30101-6. PMID 29361336.

- Crump A (May 2017). "Ivermectin: enigmatic multifaceted 'wonder' drug continues to surprise and exceed expectations". J. Antibiot. 70 (5): 495–505. doi:10.1038/ja.2017.11. PMID 28196978.

- Ōmura S (August 2016). "A Splendid Gift from the Earth: The Origins and Impact of the Avermectins (Nobel Lecture)". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55 (35): 10190–209. doi:10.1002/anie.201602164. PMID 27435664. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- James WD, Elston D, Berger T, Neuhaus I (2015). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 439. ISBN 978-0323319690.

Ivermectin treatment is emerging as a potential ancillary measure.

- Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, Coulson I (2017). Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 89. ISBN 978-0702069130.

- Carotti A, Marinozzi M, Custodi C, Cerra B, Pellicciari R, Gioiello A, Macchiarulo A (2014). "Beyond bile acids: targeting Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) with natural and synthetic ligands". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (19): 2129–42. doi:10.2174/1568026614666141112094058. PMID 25388537. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Jin L, Feng X, Rong H, Pan Z, Inaba Y, Qiu L, et al. (2013). "The antiparasitic drug ivermectin is a novel FXR ligand that regulates metabolism". Nature Communications. 4: 1937. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1937J. doi:10.1038/ncomms2924. PMID 23728580.

- Kim SG, Kim BK, Kim K, Fang S (December 2016). "Bile Acid Nuclear Receptor Farnesoid X Receptor: Therapeutic Target for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease". Endocrinology and Metabolism. 31 (4): 500–04. doi:10.3803/EnM.2016.31.4.500. PMC 5195824. PMID 28029021.

- Kaplan RM, Vidyashankar AN (May 2012). "An inconvenient truth: global worming and anthelmintic resistance". Veterinary Parasitology. 186 (1–2): 70–8. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.048. PMID 22154968.

- Geurden T, Chartier C, Fanke J, di Regalbono AF, Traversa D, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, et al. (December 2015). "Anthelmintic resistance to ivermectin and moxidectin in gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle in Europe". International Journal for Parasitology. Drugs and Drug Resistance. 5 (3): 163–71. doi:10.1016/j.ijpddr.2015.08.001. PMID 26448902.

- Peña-Espinoza M, Thamsborg SM, Denwood MJ, Drag M, Hansen TV, Jensen VF, Enemark HL (December 2016). "Efficacy of ivermectin against gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle in Denmark evaluated by different methods for analysis of faecal egg count reduction". International Journal for Parasitology. Drugs and Drug Resistance. 6 (3): 241–250. doi:10.1016/j.ijpddr.2016.10.004. PMID 27835769.

- Papich MG (January 1, 2016). "Ivermectin". In Papich MG (ed.). Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs. W.B. Saunders. pp. 420–23. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-24485-5.00323-5. ISBN 978-0-323-24485-5. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Dowling P (December 2006). "Pharmacogenetics: it's not just about ivermectin in collies". Can. Vet. J. 47 (12): 1165–68. PMC 1636591. PMID 17217086.

- "MDR1 FAQs". Australian Shepherd Health & Genetics Institute, Inc. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007.

- "Multidrug Sensitivity in Dogs". Washington State University's College of Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015.

- Frischke H, Hunt L (April 1991). "Alberta. Suspected ivermectin toxicity in kittens". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 32 (4): 245. PMC 1481314. PMID 17423775.

- "Acarexx". Boehringer Ingelheim. April 11, 2016. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- Klingenberg R (2007). Understanding reptile parasites: from the experts at Advanced Vivarium Systems. Irvine, Calif: Advanced Vivarium Systems. ISBN 978-1882770908.

- "Comfortis- spinosad tablet, chewable". DailyMed. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- "Comfortis and ivermectin interaction Safety Warning Notification". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on August 29, 2009.

External links

- "Ivermectin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- The Carter Center River Blindness (Onchocerciasis) Control Program

- "ivermectin (Rx) Stromectol". Medscape. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

- "Ivermectin Topical". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021.

| Antiparasitics – Anthelmintics (P02) and endectocides (QP54) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiplatyhelmintic agents |

| ||||||||||||||

| Antinematodal agents (including macrofilaricides) |

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Ectoparasiticides / arthropod (P03A) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insecticide/pediculicide |

| ||||||||||||||

| Acaricide/miticide/scabicide |

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||