This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 6614group6 (talk | contribs) at 17:31, 21 October 2017 (→Public health regulatory history in the United States). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:31, 21 October 2017 by 6614group6 (talk | contribs) (→Public health regulatory history in the United States)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. Please review the contents of the article and add the appropriate references if you can. Unsourced or poorly sourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Bisphenol A" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2016) |  |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name 4,4'-(propane-2,2-diyl)diphenol | |

| Other names

BPA, p,p'-Isopropylidenebisphenol, 2,2-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propane | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.133 |

| EC Number |

|

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| KEGG | |

| PubChem CID | |

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2430 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C15H16O2 |

| Molar mass | 228.291 g·mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Density | 1.20 g/cm³ |

| Melting point | 158 to 159 °C (316 to 318 °F; 431 to 432 K) |

| Boiling point | 220 °C (428 °F; 493 K) 4 mmHg |

| Solubility in water | 120–300 ppm (21.5 °C) |

| Vapor pressure | 5×10 Pa (25 °C) |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

|

| Flash point | 227 °C (441 °F; 500 K) |

| Autoignition temperature |

600 °C (1,112 °F; 873 K) |

| Related compounds | |

| Related phenols | Bisphenol S |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |

Bisphenol A (BPA) is an organic synthetic compound with the chemical formula (CH3)2C(C6H4OH)2 belonging to the group of diphenylmethane derivatives and bisphenols, with two hydroxyphenyl groups. It is a colorless solid that is soluble in organic solvents, but poorly soluble in water. It has been in commercial use since 1957.

BPA is employed to make certain plastics and epoxy resins. BPA-based plastic is clear and tough, and is made into a variety of common consumer goods, such as water bottles, sports equipment, CDs, and DVDs. Epoxy resins containing BPA are used to line water pipes, as coatings on the inside of many food and beverage cans and in making thermal paper such as that used in sales receipts. In 2015, an estimated 4 million tonnes of BPA chemical were produced for manufacturing polycarbonate plastic, making it one of the highest volume of chemicals produced worldwide.

BPA is a xenoestrogen, exhibiting estrogen-mimicking, hormone-like properties that raise concern about its suitability in some consumer products and food containers. Since 2008, several governments have investigated its safety, which prompted some retailers to withdraw polycarbonate products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has ended its authorization of the use of BPA in baby bottles and infant formula packaging, based on market abandonment, not safety. The European Union and Canada have banned BPA use in baby bottles.

The FDA states "BPA is safe at the current levels occurring in foods" based on extensive research, including two more studies issued by the agency in early 2014. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reviewed new scientific information on BPA in 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2015: EFSA's experts concluded on each occasion that they could not identify any new evidence which would lead them to revise their opinion that the known level of exposure to BPA is safe; however, the EFSA does recognize some uncertainties, and will continue to investigate them.

In February 2016, France announced that it intends to propose BPA as a REACH Regulation candidate substance of very high concern (SVHC).

Production

World production capacity of Bisphenol A was 1 million tons in the 1980s, and more than 2.2 million tons in 2009. It is a high production volume chemical. In 2003, U.S. consumption was 856,000 tons, 72% of which used to make polycarbonate plastic and 21% going into epoxy resins. In the U.S., less than 5% of the BPA produced is used in food contact applications, but remains in the canned food industry and printing applications such as sales receipts.

Bisphenol A was first synthesized by the Russian chemist Alexander Dianin in 1891. This compound is synthesized by the condensation of acetone (hence the suffix A in the name) with two equivalents of phenol. The reaction is catalyzed by a strong acid, such as hydrochloric acid (HCl) or a sulfonated polystyrene resin. Industrially, a large excess of phenol is used to ensure full condensation; the product mixture of the cumene process (acetone and phenol) may also be used as starting material:

A large number of ketones undergo analogous condensation reactions. Commercial production of BPA requires distillation – either extraction of BPA from many resinous byproducts under high vacuum or solvent-based extraction using additional phenol followed by distillation.

Uses

Further information: Polycarbonate

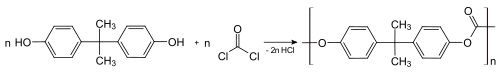

Bisphenol A is used primarily to make plastics, and products using bisphenol A-based plastics have been in commercial use since 1957. At least 3.6 million tonnes (8 billion pounds) of BPA are used by manufacturers yearly. It is a key monomer in production of epoxy resins and in the most common form of polycarbonate plastic. Bisphenol A and phosgene react to give polycarbonate under biphasic conditions; the hydrochloric acid is scavenged with aqueous base:

Diphenyl carbonate may be used in place of phosgene. Phenol is eliminated instead of hydrochloric acid. This transesterification process avoids the toxicity and handling of phosgene.

Polycarbonate plastic, which is clear and nearly shatterproof, is used to make a variety of common products including baby and water bottles, sports equipment, medical and dental devices, dental fillings sealants, CDs and DVDs, household electronics, eyeglass lenses, foundry castings, and the lining of water pipes. BPA is also used in the synthesis of polysulfones and polyether ketones, as an antioxidant in some plasticizers, and as a polymerization inhibitor in PVC. Epoxy resins containing bisphenol A are used as coatings on the inside of almost all food and beverage cans; however, due to BPA health concerns, in Japan epoxy coating was mostly replaced by PET film. Bisphenol A is also a precursor to the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol A, and was used as a fungicide.

Bisphenol A is a preferred color developer in carbonless copy paper and thermal point of sale receipt paper. When used in thermal paper, BPA is present as "free" (i.e., discrete, non-polymerized) BPA, which is likely to be more available for exposure than BPA polymerized into a resin or plastic. Upon handling, BPA in thermal paper can be transferred to skin, and there is some concern that residues on hands could be ingested through incidental hand-to-mouth contact. Furthermore, some studies suggest that dermal absorption may contribute some small fraction to the overall human exposure. European data indicate that the use of BPA in paper may also contribute to the presence of BPA in the stream of recycled paper and in landfills. Although there are no estimates for the amount of BPA used in thermal paper in the United States, in Western Europe, the volume of BPA reported to be used in thermal paper in 2005/2006 was 1,890 tonnes per year, while total production was estimated at 1,150,000 tonnes per year. (Figures taken from 2012 EPA draft paper.) Studies document potential spreading and accumulation of BPA in paper recycling, suggesting its presence for decades in paper recycling loop even after a hypothetical ban. Epoxy resin may or may not contain BPA, and is employed to bind gutta percha in some root canal procedures.

Identification in plastics

Plastic packaging is split into seven broad classes for recycling purposes by a Plastic identification code. As of 2014 there are no BPA labeling requirements for plastics in the US. "In general, plastics that are marked with Resin Identification Codes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 are very unlikely to contain BPA. Some, but not all, plastics that are marked with the Resin Identification Code 7 may be made with BPA." Type 7 is the catch-all "other" class, and some type 7 plastics, such as polycarbonate (sometimes identified with the letters "PC" near the recycling symbol) and epoxy resins, are made from bisphenol A monomer. Type 3 (PVC) may contain bisphenol A as an antioxidant in "flexible PVC" softened by plasticizers, but not rigid PVC such as pipe, windows, and siding.

History

Bisphenol A was discovered in 1891 by Russian chemist Aleksandr Dianin.

Based on research by chemists at Bayer and General Electric, BPA has been used since the 1950s to harden polycarbonate plastics, and make epoxy resin, which is contained in the lining of food and beverage containers.

In the early 1930s, the British biochemist Edward Charles Dodds tested BPA as an artificial estrogen, but found it to be 37,000 times less effective than estradiol. Dodds eventually developed a structurally similar compound, diethylstilbestrol (DES), which was used as a synthetic estrogen drug in women and animals until it was banned due to its risk of causing cancer; the ban on use of DES in humans came in 1971 and in animals, in 1979. BPA was never used as a drug. BPA's ability to mimic the effects of natural estrogen derive from the similarity of phenol groups on both BPA and estradiol, which enable this synthetic molecule to trigger estrogenic pathways in the body. Typically phenol-containing molecules similar to BPA are known to exert weak oestrogenic activities, thus it is also considered an endocrine disrupter (ED) and oestrogenic chemical. Xenoestrogens is another category the chemical BPA fits under because of its capability to interrupt the network that regulates the signals which control the reproductive development in humans and animals.

BPA has been found to bind to both of the nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs), ERα and ERβ. It is 1000- to 2000-fold less potent than estradiol. The drug can both mimic the action of estrogen and antagonize estrogen, indicating that it is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) or partial agonist of the ER. At high concentrations, BPA also binds to and acts as an antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR). In addition to receptor binding, the compound has been found to affect Leydig cell steroidogenesis, including affecting 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase and aromatase expression and interfering with LH receptor-ligand binding.

In 1997, adverse effects of low-dose BPA exposure in laboratory animals were first proposed. Modern studies began finding possible connections to health issues caused by exposure to BPA during pregnancy and during development. See US public health regulatory history and Chemical manufacturers reactions to bans. As of 2014, research and debates are ongoing as to whether BPA should be banned or not.

A 2007 study investigated the interaction between bisphenol A's and estrogen-related receptor γ (ERR-γ). This orphan receptor (endogenous ligand unknown) behaves as a constitutive activator of transcription. BPA seems to bind strongly to ERR-γ (dissociation constant = 5.5 nM), but only weakly to the ER. BPA binding to ERR-γ preserves its basal constitutive activity. It can also protect it from deactivation from the SERM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (afimoxifene). This may be the mechanism by which BPA acts as a xenoestrogen. Different expression of ERR-γ in different parts of the body may account for variations in bisphenol A effects. For instance, ERR-γ has been found in high concentration in the placenta, explaining reports of high bisphenol accumulation in this tissue. BPA has also been found to act as an agonist of the GPER (GPR30).

Safety

Health effects

According to the European Food Safety Authority "BPA poses no health risk to consumers of any age group (including unborn children, infants and adolescents) at current exposure levels". But in 2017 the European Chemicals Agency concluded that BPA should be listed as a substance of very high concern due to its properties as endocrine disruptor.

In 2012, the United States' Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned the use of BPA in baby bottles. The Natural Resources Defense Council called the move inadequate, saying the FDA needed to ban BPA from all food packaging. The FDA maintains that the agency continues to support the safety of BPA for use in products that hold food.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also holds the position that BPA is not a health concern. In 2011, Andrew Wadge, the chief scientist of the United Kingdom's Food Standards Agency, commented on a 2011 US study on dietary exposure of adult humans to BPA, saying, "This corroborates other independent studies and adds to the evidence that BPA is rapidly absorbed, detoxified, and eliminated from humans – therefore is not a health concern."

The Endocrine Society said in 2015 that the results of ongoing laboratory research gave grounds for concern about the potential hazards of endocrine-disrupting chemicals – including BPA – in the environment, and that on the basis of the precautionary principle these substances should continue to be assessed and tightly regulated. A 2016 review of the literature said that the potential harms caused by BPA were a topic of scientific debate and that further investigation was a priority because of the association between BPA exposure and adverse human health effects including reproductive and developmental effects and metabolic disease.

United States expert panel conclusions

In 2006, the US Government sponsored an assessment of the scientific literature on BPA. Thirty-eight experts in fields involved with bisphenol A gathered in Chapel Hill, North Carolina to review several hundred studies on BPA, many conducted by members of the group. At the end of the meeting, the group issued the Chapel Hill Consensus Statement, which stated "BPA at concentrations found in the human body is associated with organizational changes in the prostate, breast, testis, mammary glands, body size, brain structure and chemistry, and behavior of laboratory animals." The Chapel Hill Consensus Statement stated that average BPA levels in people were above those that cause harm to many animals in laboratory experiments. It noted that while BPA is not persistent in the environment or in humans, biomonitoring surveys indicate that exposure is continuous. This is problematic because acute animal exposure studies are used to estimate daily human exposure to BPA, and no studies that had examined BPA pharmacokinetics in animal models had followed continuous low-level exposures. The authors added that measurement of BPA levels in serum and other body fluids suggests the possibilities that BPA intake is much higher than accounted for or that BPA can bioaccumulate in some conditions (such as pregnancy).

Metabolic disease

Main article: ObesityNumerous animal studies have demonstrated an association between endocrine disrupting chemicals (including BPA) and obesity. However, the relationship between bisphenol A exposure and obesity in humans is unclear. Proposed mechanisms for BPA exposure to increase the risk of obesity include BPA-induced thyroid dysfunction, activation of the PPAR-gamma receptor, and disruption of neural circuits that regulate feeding behavior. BPA works by imitating the natural hormone 17B-estradiol. In the past BPA has been considered a weak mimicker of estrogen but newer evidence indicates that it is a potent mimicker. When it binds to estrogen receptors it triggers alternative estrogenic effects that begin outside of the nucleus. This different path induced by BPA has been shown to alter glucose and lipid metabolism in animal studies.

There are different effects of BPA exposure during different stages of development. During adulthood, BPA exposure modifies insulin sensitivity and insulin release without affecting weight.

Thyroid function

Main article: Thyroid

A 2007 review concluded that bisphenol-A has been shown to bind to thyroid hormone receptor and perhaps has selective effects on its functions.

A 2009 review about environmental chemicals and thyroid function raised concerns about BPA effects on triiodothyronine and concluded that "available evidence suggests that governing agencies need to regulate the use of thyroid-disrupting chemicals, particularly as such uses relate exposures of pregnant women, neonates and small children to the agents".

A 2009 review summarized BPA adverse effects on thyroid hormone action.

Neurological effects

Limited epidemiological evidence suggests that exposure to BPA in the uterus and during childhood is associated with poor behavioral outcomes in humans. Exposure may be associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and aggression in children. A panel convened by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health determined that there was "some concern" about BPA's effects on fetal and infant brain development and behavior. In January 2010, based on the NTP report, the FDA expressed the same level of concern.

A 2007 literature review concluded that BPA, like other chemicals that mimic estrogen (xenoestrogens), should be considered as a player within the nervous system that can regulate or alter its functions through multiple pathways. A 2008 review of animal research found that low-dose BPA maternal exposure can cause long-term consequences for the neurobehavioral development in mice.

A 2009 review raised concerns about a BPA effect on the anteroventral periventricular nucleus.

Disruption of the dopaminergic system

Main article: Dopaminergic system

A 2008 review of human participants has concluded that BPA mimics estrogenic activity and affects various dopaminergic processes to enhance mesolimbic dopamine activity resulting in hyperactivity, attention deficits, and a heightened sensitivity to drugs of abuse.

Cancer

According to the WHO's INFOSAN, carcinogenicity studies conducted under the US National Toxicology Program, have shown increases in leukemia and testicular interstitial cell tumors in male rats. However, according to the note "these studies have not been considered as convincing evidence of a potential cancer risk because of the doubtful statistical significance of the small differences in incidences from controls."

A 2010 review concluded that bisphenol A may increase cancer risk.

At least one study suggested that bisphenol A suppresses DNA methylation, which is involved in epigenetic changes.

Breast cancer

Further information: Risk factors of breast cancer § Bisphenol A

Higher susceptibility to breast cancer has been found in many studies of rodents and primates exposed to BPA. However, the association between BPA and subsequent development of breast cancer in humans is unclear.

Neuroblastoma

BPA promotes the growth, invasiveness and metastasis of cells from a laboratory neuroblastoma cancer cell line, SK-N-SH.

Fertility

As of 2013, the evidence to support a link between BPA exposure and male infertility is weak though limited evidence does support an association with lower sperm quality. There is tentative evidence to support the idea that BPA exposure has negative effects on human fertility. Few studies have investigated whether recurrent miscarriage is associated with BPA levels. Exposure to BPA does not appear to be linked with higher rates of endometrial hyperplasia.

Sexual function

Higher BPA exposure has been associated with increased self-reporting of decreased male sexual function but few studies examining this relationship have been conducted.

Asthma

Studies in mice have found a link between BPA exposure and asthma; a 2010 study on mice has concluded that perinatal exposure to 10 µg/ml of BPA in drinking water enhances allergic sensitization and bronchial inflammation and responsiveness in an animal model of asthma. A study published in JAMA pediatrics has found that prenatal exposure to BPA is also linked to lower lung capacity in some young children. This study had 398 mother-infant pairs and looked at their urine samples to detect concentrations of BPA. They study found that every 10-fold increase in BPA was tied to a 55% increase in the odds of wheezing. The higher the concentration of BPA during pregnancy were linked to decrease lung capacity in children under four years old but the link disappeared at age 5. Associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland School of Medicine said, "Exposure during pregnancy, not after, appears to be the critical time for BPA, possibly because it's affecting important pathways that help the lung develop."

In 2013, research from scientists at the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health also found a link between the compound and an increased risk for asthma. The research team reported that children with higher levels of BPA at ages 3, 5 and 7 had increased odds of developing asthma when they were between the ages of 5 and 12. The children in this study had about the same concentration of BPA exposure as the average U.S child. Dr. Kathleen Donohue, an instructor at Columbia University Medical Center said, "they saw an increased risk of asthma at fairly routine, low doses of BPA." Kim Harley, who studies environmental chemicals and children's health, commented in the Scientific American journal saying while the study does not show that BPA causes asthma or wheezing, "it's an important study because we don't know a lot right now about how BPA affects immune response and asthma...They measured BPA at different ages, measured asthma and wheeze at multiple points, and still found consistent associations."

Animal research

The first evidence of the estrogenicity of bisphenol A came from experiments on rats conducted in the 1930s, but it was not until 1997 that adverse effects of low-dose exposure on laboratory animals were first reported. Bisphenol A is an endocrine disruptor that can mimic estrogen and has been shown to cause negative health effects in animal studies. Bisphenol A closely mimics the structure and function of the hormone estradiol by binding to and activating the same estrogen receptor as the natural hormone. Early developmental stages appear to be the period of greatest sensitivity to its effects, and some studies have linked prenatal exposure to later physical and neurological difficulties.

| Dose (µg/kg*day) | Effects (measured in studies of mice or rats, descriptions (in quotes) are from Environmental Working Group) |

Study Year |

|---|---|---|

| 0.025 | "Permanent changes to genital tract" | 2005 |

| 0.025 | "Changes in breast tissue that predispose cells to hormones and carcinogens" | 2005 |

| 1 | long-term adverse reproductive and carcinogenic effects | 2009 |

| 2 | "increased prostate weight 30%" | 1997 |

| 2 | "lower bodyweight, increase of anogenital distance in both genders, signs of early puberty and longer estrus." | 2002 |

| 2.4 | "Decline in testicular testosterone" | 2004 |

| 2.5 | "Breast cells predisposed to cancer" | 2007 |

| 10 | "Prostate cells more sensitive to hormones and cancer" | 2006 |

| 10 | "Decreased maternal behaviors" | 2002 |

| 30 | "Reversed the normal sex differences in brain structure and behavior" | 2003 |

| 50 | Adverse neurological effects occur in non-human primates | 2008 |

| 50 | Disrupts ovarian development | 2009 |

A study from 2008 concluded that blood levels of bisphenol A in neonatal mice are the same whether it is injected or ingested. The current U.S. human exposure limit set by the EPA is 50 µg/kg/day. In a 2010 commentary a group of scientists criticized a study designed to test low dose BPA exposure published in "Toxicological Sciences" and a later editorial by the same journal, which claimed the rats used in the study were insensitive to estrogen and that had other problems like the use of BPA-containing polycabonate cages while the authors disagreed.

Different expression of ERR-γ in different parts of the body may account for variations in bisphenol A effects. For instance, ERR-γ has been found in high concentration in the placenta, explaining reports of high bisphenol accumulation in this tissue.

Environmental risk

In 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported that over one million pounds of BPA are released into the environment annually. BPA can enter the environment either directly from chemical, plastics. coat and staining manufacturers, from paper or material recycling companies, foundries who use BPA in casting sand, or indirectly leaching from plastic, paper and metal waste in landfills. or ocean-borne plastic trash. Despite a soil half-life of only 1–10 days, BPA's ubiquity makes it an important pollutant; It was shown to interfere with nitrogen fixation at the roots of leguminous plants associated with the bacterial symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti.

A 2005 study conducted in the US had found that 91–98% of BPA may be removed from water during treatment at municipal water treatment plants. Nevertheless, a 2009 meta-analysis of BPA in the surface water system showed BPA present in surface water and sediment in the US and Europe. According to Environment Canada in 2011, "BPA can currently be found in municipal wastewater. initial assessment shows that at low levels, bisphenol A can harm fish and organisms over time.

BPA affects growth, reproduction, and development in aquatic organisms. Among freshwater organisms, fish appear to be the most sensitive species. Evidence of endocrine-related effects in fish, aquatic invertebrates, amphibians, and reptiles has been reported at environmentally relevant exposure levels lower than those required for acute toxicity. There is a widespread variation in reported values for endocrine-related effects, but many fall in the range of 1μg/L to 1 mg/L.

A 2009 review of the biological impacts of plasticizers on wildlife published by the Royal Society with a focus on aquatic and terrestrial annelids, molluscs, crustaceans, insects, fish and amphibians concluded that BPA affects reproduction in all studied animal groups, impairs development in crustaceans and amphibians and induces genetic aberrations.

Positions of national and international bodies

World Health Organization

In November 2009, the WHO announced to organize an expert consultation in 2010 to assess low-dose BPA exposure health effects, focusing on the nervous and behavioral system and exposure to young children. The 2010 WHO expert panel recommended no new regulations limiting or banning the use of bisphenol-A, stating that "initiation of public health measures would be premature."

United States

In 2013, the FDA posted on its web site: "Is BPA safe? Yes. Based on FDA's ongoing safety review of scientific evidence, the available information continues to support the safety of BPA for the approved uses in food containers and packaging. People are exposed to low levels of BPA because, like many packaging components, very small amounts of BPA may migrate from the food packaging into foods or beverages." FDA issued a statement on the basis of three previous reviews by a group of assembled Agency experts in 2014 in its "Final report for the review of literature and data on BPA" that said in part, "The results of these new toxicity data and studies do not affect the dose-effect level and the existing NOAEL (5 mg/kg bw/day; oral exposure)."

Australia and New Zealand

In 2009 the Australia and New Zealand Food Safety Authority (Food Standards Australia New Zealand) did not see any health risk with bisphenol A baby bottles if the manufacturer's instructions were followed, as levels of exposure were very low and would not pose a significant health risk. It added that "the move by overseas manufacturers to stop using BPA in baby bottles is a voluntary action and not the result of a specific action by regulators." In 2008 it had suggested the use of glass baby bottles if parents had concerns.

In 2012 the Australian Government introduced a voluntary phase out of BPA use in polycarbonate baby bottles.

Canada

In April 2008, Health Canada concluded that, while adverse health effects were not expected, the margin of safety was too small for formula-fed infants and proposed classifying the chemical as "'toxic' to human health and the environment." The Canadian Minister of Health announced Canada's intent to ban the import, sale, and advertisement of polycarbonate baby bottles containing bisphenol A due to safety concerns, and investigate ways to reduce BPA contamination of baby formula packaged in metal cans. Subsequent news reports from April 2008 showed many retailers removing polycarbonate drinking products from their shelves. On 18 October 2008, Health Canada noted that "bisphenol A exposure to newborns and infants is below levels that cause effects" and that the "general public need not be concerned".

In 2010, Canada's department of the environment declared BPA to be a "toxic substance" and added it to schedule 1 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999.

European Union

The 2008 European Union Risk Assessment Report on bisphenol A, published by the European Commission and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), concluded that bisphenol A-based products, such as polycarbonate plastic and epoxy resins, are safe for consumers and the environment when used as intended. By October 2008, after the Lang Study was published, the EFSA issued a statement concluding that the study provided no grounds to revise the current Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI) level for BPA of 0.05 mg/kg bodyweight.

On 22 December 2009, the EU Environment ministers released a statement expressing concerns over recent studies showing adverse effects of exposure to endocrine disruptors.

In September 2010, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded after a "comprehensive evaluation of recent toxicity data that no new study could be identified, which would call for a revision of the current TDI". The Panel noted that some studies conducted on developing animals have suggested BPA-related effects of possible toxicological relevance, in particular biochemical changes in brain, immune-modulatory effects and enhanced susceptibility to breast tumours but considered that those studies had several shortcomings so the relevance of these findings for human health could not be assessed.

On 25 November 2010, the European Union executive commission said it planned to ban the manufacturing by 1 March 2011 and ban the marketing and market placement of polycarbonate baby bottles containing the organic compound bisphenol A by 1 June 2011, according to John Dalli, commissioner in charge of health and consumer policy. This was backed by a majority of EU governments. The ban was called an over-reaction by Richard Sharpe, of the Medical Research Council's Human Reproductive Sciences Unit, who said to be unaware of any convincing evidence justifying the measure and criticized it as being done on political, rather than scientific grounds.

In January 2011 use of bisphenol A in baby bottles was forbidden in all EU-countries.

After reviewing more recent research, in 2012 EFSA made a decision to re-evaluate the human risks associated with exposure to BPA. They completed a draft assessment of consumer exposure to BPA in July 2013 and at that time asked for public input from all stakeholders to assist in forming a final report, which is expected to be completed in 2014.

In January 2014, EFSA presented a second part of the draft opinion which discussed the human health risks posed by BPA. The draft opinion was accompanied by an eight-week public consultation and also included adverse effects on the liver and kidney as related to BPA. From this it was recommended that the current TDI to be revised. In January 2015 EFSA indicated that the TDI was reduced from 50 to 4 µg/kg body weight/day – a recommendation, as national legislatures make the laws.

The EU Commission issued a new regulation regarding the use of bisphenol A in thermal paper on 12 December 2016. According to this new regulation, thermal paper containing bisphenol A cannot be placed on the EU market after 2 January 2020. This regulation came into effect on 2 January 2017 but there is a transition period of three years.

On 12 January 2017, BPA was added to the candidate list of substances of very high concern (SVHC). Candidate SVHC listing is a first step towards restricting the importing and use of a chemical in the EU. If the European Chemical Agency assigns SVHC status, the presence of BPA in a product at a concentration above 0.1% must be disclosed to a purchaser (with different rules for consumer and business purchasers). In February 2016, France had announced that it intended to propose BPA as a candidate SVHC by 8 August 2016.

Denmark

In May 2009, the Danish parliament passed a resolution to ban the use of BPA in baby bottles, which had not been enacted by April 2010. In March 2010, a temporary ban was declared by the Health Minister.

Belgium

On March 2010, senator Philippe Mahoux proposed legislation to ban BPA in food contact plastics. On May 2011, senators Dominique Tilmans and Jacques Brotchi proposed legislation to ban BPA from thermal paper.

France

On 5 February 2010, the French Food Safety Agency (AFSSA) questioned the previous assessments of the health risks of BPA, especially in regard to behavioral effects observed in rat pups following exposure in utero and during the first months of life. In April 2010, the AFFSA suggested the adoption of better labels for food products containing BPA.

On 24 March 2010, the French Senate unanimously approved a proposition of law to ban BPA from baby bottles. The National Assembly (Lower House) approved the text on 23 June 2010, which has been applicable law since 2 July 2010. On 12 October 2011, the French National Assembly voted a law forbidding the use of Bisphenol A in products aimed at less than 3-year-old children for 2013, and 2014 for all food containers.

On 9 October 2012, the French Senate adopted unanimously the law proposition to suspend manufacture, import, export and marketing of all food containers that include bisphenol A for 2015. The ban of bisphenol A in 2013 for food products designed for children less than 3-years-old was maintained.

Germany

On 19 September 2008, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung, BfR) stated that there was no reason to change the current risk assessment for bisphenol A on the basis of the Lang Study.

In October 2009, the German environmental organization Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland requested a ban on BPA for children's products, especially pacifiers, and products that make contact with food. In response, some manufacturers voluntarily removed the problematic pacifiers from the market.

Netherlands

On 3 March 2016, the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority [nl] (NVWA) issued cautionary recommendations to the Minister of Health, Welfare, and Sport and the Secretary for Economic Affairs, on the public intake of BPA, especially for vulnerable groups such as women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and those with developing immune systems such as children below the age of 10. This was done in response to recent published research, and conclusions reached by the European Food Safety Authority. It also called for the concentration of BPA in drinking water to be lowered below 0.2 µg/L, in line with the maximum tolerable intake they recommend.

Switzerland

In February 2009, the Swiss Federal Office for Public Health, based on reports of other health agencies, stated that the intake of bisphenol A from food represents no risk to the consumer, including newborns and infants. However, in the same statement, it advised for proper use of polycarbonate baby bottles and listed alternatives.

Sweden

By May 26, 1995, the Swedish Chemicals Agency asked for a BPA ban in baby bottles, but the Swedish Food Safety Authority prefers to await the expected European Food Safety Authority's updated review. The Minister of Environment said to wait for the EFSA review but not for too long. From March 2011 it is prohibited to manufacture babybottles containing bisphenol A and from July 2011 they can not be bought in stores. On 12 April 2012, the Swedish government announced that Sweden will ban BPA in cans containing food for children under the age of three.

United Kingdom

In December 2009, responding to a letter from a group of seven scientists that urged the UK Government to "adopt a standpoint consistent with the approach taken by other Governments who have ended the use of BPA in food contact products marketed at children", the UK Food Standards Agency reaffirmed, in January 2009, its view that "exposure of UK consumers to BPA from all sources, including food contact materials, was well below levels considered harmful".

Turkey

As of 10 June 2011, Turkey banned the use of BPA in baby bottles and other PC items produced for babies.

Japan

Between 1998 and 2003, the canning industry voluntarily replaced its BPA-containing epoxy resin can liners with BPA-free polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in many of its products. For other products, it switched to a different epoxy lining that yielded much less migration of BPA into food than the previously used resin. In addition, polycarbonate tableware for school lunches was replaced by BPA-free plastics. As a result of these changes, Japanese risk assessors have found that virtually no BPA is detectable in canned foods or drinks, and blood levels of BPA in the Japanese people have declined up to 50% in one study.

Human exposure sources

The major human exposure route to BPA is diet, including ingestion of contaminated food and water. Bisphenol A is leached from the lining of food and beverage cans where it is used as an ingredient in the plastic used to protect the food from direct contact with the can. It is especially likely to leach from plastics when they are cleaned with harsh detergents or when they contain acidic or high-temperature liquids. BPA is used to form epoxy resin coating of water pipes; in older buildings, such resin coatings are used to avoid replacement of deteriorating pipes. In the workplace, while handling and manufacturing products which contain BPA, inhalation and dermal exposures are the most probable routes. There are many uses of BPA for which related potential exposures have not been fully assessed including digital media, electrical and electronic equipment, automobiles, sports safety equipment, electrical laminates for printed circuit boards, composites, paints, and adhesives. In addition to being present in many products that people use on a daily basis, BPA has the ability to bioaccumulate, especially in water bodies. In one review, it was seen that although BPA is biodegradable, it is still detected after wastewater treatment in many waterways at concentrations of approximately 1 ug/L. This study also looked at other pathways where BPA could potentially bioaccumulate and found "low-moderate potential...in microorganisms, algae, invertebrates, and fish in the environment" suggesting that some environmental exposures less likely.

In November 2009, the Consumer Reports magazine published an analysis of BPA content in some canned foods and beverages, where in specific cases the content of a single can of food could exceed the FDA "Cumulative Exposure Daily Intake" limit.

The CDC had found bisphenol A in the urine of 95% of adults sampled in 1988–1994 and in 93% of children and adults tested in 2003–04. The USEPA Reference Dose (RfD) for BPA is 50 µg/kg/day which is not enforceable but is the recommended safe level of exposure. The most sensitive animal studies show effects at much lower doses, and several studies of children, who tend to have the highest levels, have found levels over the EPA's suggested safe limit figure.

A 2009 Health Canada study found that the majority of canned soft drinks it tested had low, but measurable levels of bisphenol A. A study conducted by the University of Texas School of Public Health in 2010 found BPA in 63 of 105 samples of fresh and canned foods, including fresh turkey sold in plastic packaging and canned infant formula. A 2011 study published in Environmental Health Perspectives, "Food Packaging and Bisphenol A and Bis(2-Ethyhexyl) Phthalate Exposure: Findings from a Dietary Intervention," selected 20 participants based on their self-reported use of canned and packaged foods to study BPA. Participants ate their usual diets, followed by three days of consuming foods that were not canned or packaged. The study's findings include: 1) evidence of BPA in participants' urine decreased by 50% to 70% during the period of eating fresh foods; and 2) participants' reports of their food practices suggested that consumption of canned foods and beverages and restaurant meals were the most likely sources of exposure to BPA in their usual diets. The researchers note that, even beyond these 20 participants, BPA exposure is widespread, with detectable levels in urine samples in more than an estimated 90% of the U.S. population. Another U.S. study found that consumption of soda, school lunches, and meals prepared outside the home were statistically significantly associated with higher urinary BPA.

A 2011 experiment by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health indicated that BPA used in the lining of food cans is absorbed by the food and then ingested by consumers. Of 75 participants, half ate a lunch of canned vegetable soup for five days, followed by five days of fresh soup, while the other half did the same experiment in reverse order. "The analysis revealed that when participants ate the canned soup, they experienced more than a 1,000 percent increase in their urinary concentrations of BPA, compared to when they dined on fresh soup." A 2009 study found that drinking from polycarbonate bottles increased urinary bisphenol A levels by two thirds, from 1.2 μg/g creatinine to 2 μg/g creatinine. Consumer groups recommend that people wishing to lower their exposure to bisphenol A avoid canned food and polycarbonate plastic containers (which shares resin identification code 7 with many other plastics) unless the packaging indicates the plastic is bisphenol A-free. To avoid the possibility of BPA leaching into food or drink, the National Toxicology Panel recommends avoiding microwaving food in plastic containers, putting plastics in the dishwasher, or using harsh detergents.

Besides diet, exposure can also occur through air and through skin absorption. Free BPA is found in high concentration in thermal paper and carbonless copy paper, which would be expected to be more available for exposure than BPA bound into resin or plastic. Popular uses of thermal paper include receipts, event and cinema tickets, labels, and airline tickets. A Swiss study found that 11 of 13 thermal printing papers contained 8 – 17 g/kg bisphenol A (BPA). Upon dry finger contact with a thermal paper receipt, roughly 1 μg BPA (0.2 – 6 μg) was transferred to the forefinger and the middle finger. For wet or greasy fingers approximately 10 times more was transferred. Extraction of BPA from the fingers was possible up to 2 hours after exposure. Further, it has been demonstrated that thermal receipts placed in contact with paper currency in a wallet for 24 hours cause a dramatic increase in the concentration of BPA in paper currency, making paper money a secondary source of exposure. Another study has identified BPA in all of the waste paper samples analysed (newspapers, magazines, office paper, etc.), indicating direct results of contamination through paper recycling. Free BPA can readily be transferred to skin, and residues on hands can be ingested. Bodily intake through dermal absorption (99% of which comes from handling receipts) has been shown for the general population to be 0.219 ng/kg bw/day (occupationally exposed persons absorb higher amounts at 16.3 ng/kg bw/day) whereas aggregate intake (food/beverage/environment) for adults is estimated at 0.36–0.43 μg/kg bw/day (estimated intake for occupationally exposed adults is 0.043–100 μg/kg bw/day).

A study from 2011 found that Americans of all age groups had twice as much BPA in their bodies as Canadians; the reasons for the disparity were unknown, as there was no evidence to suggest higher amounts of BPA in U.S. foods, or that consumer products available in the U.S. containing BPA were BPA-free in Canada. According to another study it may have been due to differences in how and when the surveys were done, because "although comparisons of measured concentrations can be made across populations, this must be done with caution owing to differences in sampling, in the analytical methods used and in the sensitivity of the assays."

Comparing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) from four time periods between 2003 and 2012, urinary BPA data the median daily intake for the overall population is approximately 25 ng/kg/day and below current health based guidelines. Additionally, daily intake of BPA in the United States has decreased significantly compared to the intakes measured in 2003–2004. Public attention and governmental action during this time period may have decreased the exposure to BPA somewhat but these studies did not include children under the age of six. According to the Endocrine Society, age of exposure is an important factor in determining the extent to which endocrine disrupting chemicals will have an effect, and the effects on developing fetuses or infants is quite different than an adult.

Fetal and early-childhood exposures

A 2009 study found higher urinary concentrations in young children than in adults under typical exposure scenarios. In adults, BPA is eliminated from the body through a detoxification process in the liver. In infants and children, this pathway is not fully developed so they have a decreased ability to clear BPA from their systems. Several recent studies of children have found levels that exceed the EPAs suggested safe limit figure.

Infants fed with liquid formula are among the most exposed, and those fed formula from polycarbonate bottles can consume up to 13 micrograms of bisphenol A per kg of body weight per day (μg/kg/day; see table below). In the US and Canada, BPA has been found in infant liquid formula in concentrations varying from 0.48 to 11 ng/g. BPA has been rarely found in infant powder formula (only 1 of 14). The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) states that "the benefit of a stable source of good nutrition from infant formula and food outweighs the potential risk of BPA exposure". BPA is present in human breast milk, having been found by several studies in 62–75% of breast milk samples.

Children may be more susceptible to BPA exposure than adults (see health effects). A 2010 study of people in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany has suggested polycarbonate (PC) baby bottles as the most prominent role of exposure for infants, and canned food for adults and teenagers. In the United States, the growing concern over BPA exposure in infants in recent years has led the manufacturers of plastic baby bottles to stop using BPA in their bottles. The FDA banned the use of BPA in baby bottles and sippy cups (July 2012) as well as the use of epoxy resins in infant formula packaging. However, babies may still be exposed if they are fed with old or hand-me-down bottles bought before the companies stopped using BPA.

One often overlooked source of exposure occurs when a pregnant woman is exposed, thereby exposing the fetus. Animal studies have shown that BPA can be found in both the placenta and the amniotic fluid of pregnant mice. Since BPA was also "detected in the urine and serum of pregnant women and the serum, plasma, and placenta of newborn infants" a study to examine the externalizing behaviors associated with prenatal exposure to BPA was performed which suggests that exposures earlier in development have more of an effect on the behavior outcomes and that female children (2-years-old) are impacted more than males. A small US study in 2009, funded by the Environmental Working Group, detected an average of 2.8 ng/mL BPA in the blood of 9 out of the 10 umbilical cords tested. A study of 244 mothers indicated that exposure to BPA before birth could affect the behavior of girls at age 3. Girls whose mother's urine contained high levels of BPA during pregnancy scored worse on tests of anxiety and hyperactivity. Although these girls still scored within a normal range, for every 10-fold increase in the BPA of the mother, the girls scored at least six points lower on the tests. Boys did not seem to be affected by their mother's BPA levels during pregnancy. After the baby is born, maternal exposure can continue to affect the infant through transfer of BPA to the infant via breast milk. Because of these exposures that can occur both during and after pregnancy, mothers wishing to limit their child's exposure to BPA should attempt to limit their own exposures during that time period.

While the majority of exposures have been shown to come through the diet, accidental ingestion can also be considered a source of exposure. One study conducted in Japan tested plastic baby books to look for possible leaching into saliva when babies chew on them. While the results of this study have yet to be replicated, it gives reason to question whether exposure can also occur in infants through ingestion by chewing on certain books or toys.

| Population | Estimated daily bisphenol A intake (μg/kg body weight/day). Table adapted from the National Toxicology Program Expert Panel Report. |

|---|---|

| Infant (0–6 months) formula-fed (lower number assumes weight of 4.5 kg and intake of 700 ml/day with maximum concentration of BPA detected in U.S. canned formula; higher number assumes weight of 6.1 kg and intake of 1060 ml/day from powdered formula in cans with epoxy linings and using polycarbonate bottles) |

|

| Infant (0–6 months) breast-fed (lower number assumes weight of 6.1 kg and intake of 1060 ml/day with maximum concentration of BPA detected in Japanese breast milk samples; higher number assumes weight of 4.5 kg and intake of 700 ml/day with maximum concentration of free BPA detected in U.S. breast milk samples) |

|

| Infant (6–12 months) | |

| Child (1.5–6 years) | |

| Adult (general population) | |

| Adult (occupational) |

Regulation

Public health regulatory history in the United States

In 1977, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) initiated a carcinogenesis of BPA under the National Carcinogenesis Bioassay Program. After the National Toxicology Program (NTP) was established to coordinate federal toxicological research, Congress determined that the General Accounting Office (GAO) would investigate the quality of private research for the Carcinogenesis Bioassay Program because federal oversight of private laboratories was under considerable scrutiny. Many fraudulent practices and poor quality of measures were found after the federal investigation of Industrial Bio-Test in 1976 and the investigation of contracted laboratories under the NCI in 1979. Despite the findings, the NCI and the NTP did not require reassessments of BPA’s carcinogenicity and concluded there was “no convincing evidence” of carcinogenicity. After the NTP released a final report on the carcinogenesis study, it provided the basis for the first regulatory safety standard for BPA set by the EPA in 1988, which was later adopted by the FDA as a reference dose.

The first published BPA study after the NTP report was in 1998 in Vom Saal’s laboratory where findings showed some concerns with low-dose effects of BPA. Two additional papers on the low-dose effects published in 1997 and 1998 collectively challenged the presumption that BPA was considered a weak estrogen. In the U.S., BPA ranks in the top 2 percent of high-production-volume chemicals. In 2000, the EPA requested that the NTP review the research on the effects of low doses of BPA. In 2001, the NTP’s report concluded that there was substantial, credible evidence indicating adverse effects from BPA exposure below the safety standard level of 50 micrograms/kilograms/day. Unfortunately, two studies were also presented with considerable evidence demonstrating that there are minimal to no effects due to BPA exposure. It should be noted however that these were conducted by laboratories sponsored by a chemical industry.

The first legal responses to BPA were in 2008 when many consumers filed class action lawsuits on manufacturers that sold and distributed baby products containing BPA without informing the public about the potential negative health effects. Charles Schumer introduced a 'BPA-Free Kids Act of 2008' to the U.S. Senate seeking to ban BPA in any product designed for use by children and require the Center for Disease Control to conduct a study on the health effects of BPA exposure. If any amount of BPA was detected in children’s products, it would be treated as a hazardous substance under the Federal Hazardous Substances Act. The bill was reintroduced in 2009 in both Senate and House, but died in committee each time. In 2008, the FDA reassured consumers that current limits were safe, but convened an outside panel of experts to review the issue. The Lang study was released, and co-author David Melzer presented the results of the study before the FDA panel. An editorial accompanying the Lang study's publication criticized the FDA's assessment of bisphenol A: "A fundamental problem is that the current ADI for BPA is based on experiments conducted in the early 1980s using outdated methods (only very high doses were tested) and insensitive assays. More recent findings from independent scientists were rejected by the FDA, apparently because those investigators did not follow the outdated testing guidelines for environmental chemicals, whereas studies using the outdated, insensitive assays (predominantly involving studies funded by the chemical industry) are given more weight in arriving at the conclusion that BPA is not harmful at current exposure levels." The FDA was criticized that it was "basing its conclusion on two studies while downplaying the results of hundreds of other studies." Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Research Center for Women and Families, criticized the FDA in her testimony at the FDA's public meeting on the draft assessment of bisphenol A for use in food contact applications, that "At the very least, the FDA should require a prominent warning on products made with BPA".

In March 2009 Suffolk County, New York became the first county to pass legislation to ban baby beverage containers made with bisphenol A. By March 2009, legislation to ban bisphenol A had been proposed in both House and Senate. In the same month, Rochelle Tyl, author of two studies used by FDA to assert BPA safety in August 2008, said those studies did not claim that BPA is safe because they were not designed to cover all aspects of the chemical's effects. In May 2009, Chicago and Minnesota became the first city and state, respectively, to ban BPA in baby bottles and children’s cups (Dooley, 2009). In June 2009, the FDA announced its decision to reconsider the BPA safety levels. Grassroots political action led Connecticut to become the first US state to ban bisphenol A not only from infant formula and baby food containers, but also from any reusable food or beverage container. In July 2009, the California Environmental Protection Agency's Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity Identification Committee in the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment unanimously voted against placing Bisphenol A on the state's list of chemicals that are believed to cause reproductive harm. The panel was concerned over the growing scientific evidence showing BPA's reproductive harm in animals, found that there was insufficient data on the effects in humans. Critics pointed out that the same panel failed to add second-hand smoke to the list until 2006, and only one chemical was added to the list in the last three years. In September, the US Environmental Protection Agency announced that it was evaluating BPA for an action plan development. In October, the NIH announced $30,000,000 in stimulus grants to study the health effects of BPA. This money was supposed to result in many peer-reviewed publications.

On 15 January 2010, the FDA expressed "some concern" (the middle level in its scale of concerns), about the potential effects of BPA on the brain, behavior, and prostate gland in fetuses, infants, and young children. Inconsistent messages about BPA safety have generated considerable public concern, highlighting how human risk assessment of BPA is both uncoordinated and controversial. After this concern, the FDA announced that it was taking reasonable steps to reduce human exposure to BPA in the food supply. However, the FDA was not recommending that families change the use of infant formula or foods, as it saw the benefit of a stable source of good nutrition as outweighing the potential risk from BPA exposure. On the same date, the Department of Health and Human Services released information to help parents to reduce children's BPA exposure. As of 2010, many US states were considering some sort of BPA ban.

In June 2010 the 2008–2009 Annual Report of the President's Cancer Panel was released and recommended: "Because of the long latency period of many cancers, the available evidence argues for a precautionary approach to these diverse chemicals, which include (…) bisphenol A.". In August 2010, the Maine Board of Environmental Protection voted unanimously to ban the sale of baby bottles and other reusable food and beverage containers made with bisphenol A as of January 2012. In February 2011, the newly elected governor of Maine, Paul LePage, gained national attention when he spoke on a local TV news show saying he hoped to repeal the ban because, "There hasn't been any science that identifies that there is a problem" and added: "The only thing that I've heard is if you take a plastic bottle and put it in the microwave and you heat it up, it gives off a chemical similar to estrogen. So the worst case is some women may have little beards." In April 2011, the Maine legislature passed a bill to ban the use of BPA in baby bottles, sippy cups, and other reusable food and beverage containers, effective 1 January 2012. Governor LePage refused to sign the bill. In October 2011, California banned BPA from baby bottles and toddlers' drinking cups, effective 1 July 2013. By 2011, 26 states had proposed legislation that would ban certain uses of BPA. Many bills died in committee. In July 2011, the American Medical Association (AMA) declared feeding products for babies and infants that contain BPA should be banned. It recommended better federal oversight of BPA and clear labeling of products containing it. It stressed the importance of the FDA to "actively incorporate current science into the regulation of food and beverage BPA-containing products." In 2011, The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) decided to file suit against the FDA because of the failure to respond to their petition requesting that the FDA ban BPA in food packaging and containers’. On March 31, 2012, the FDA was required to respond to the petition and ultimately rejected the NRDC petition.

In 2012, the FDA concluded an assessment of scientific research on the effects of BPA and stated in the March 2012 Consumer Update that "the scientific evidence at this time does not suggest that the very low levels of human exposure to BPA through the diet are unsafe" although recognizing "potential uncertainties in the overall interpretation of these studies including route of exposure used in the studies and the relevance of animal models to human health. The FDA is continuing to pursue additional research to resolve these uncertainties." Yet on 17 July 2012, the FDA banned BPA from baby bottles and sippy cups. An FDA spokesman said the agency's action was not based on safety concerns and that "the agency continues to support the safety of BPA for use in products that hold food." Since manufacturers had already stopped using the chemical in baby bottles and sippy cups, the decision was a response to a request by the American Chemistry Council, the chemical industry's main trade association, who believed that a ban would boost consumer confidence. The ban was criticized as "purely cosmetic" by the Environmental Working Group, which stated that "If the agency truly wants to prevent people from being exposed to this toxic chemical associated with a variety of serious and chronic conditions it should ban its use in cans of infant formula, food, and beverages." The Natural Resources Defense Council called the move inadequate saying;, the FDA needs to ban BPA from all food packaging. FDA’s current ban still does not address the use of polycarbonates in other infant products such as pacifiers, teethers, or plastic tableware. As of 2014, 12 states had banned BPA from children's bottles and feeding containers. Connecticut along with ten other states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation or regulation restrictions on the use of BPA, including; California, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Environmental regulation in the United States

On 30 December 2009 EPA released a so-called action plan for four chemicals, including BPA, which would have added it to the list of "chemicals of concern" regulated under the Toxic Substances Control Act. In February 2010, after lobbyists for the chemical industry had met with administration officials, the EPA delayed BPA regulation by not including the chemical.

On 29 March 2010, EPA published a revised action plan for BPA as "chemical of concern". In October 2010 an advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for BPA testing was published in the Federal Register July 2011. After more than 3 years at the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), part of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which has to review draft proposals within 3 months, OIRA had not done so.

In September 2013 EPA withdrew its 2010 draft BPA rule. saying the rule was "no longer necessary", because EPA was taking a different track at looking at chemicals, a so-called "Work Plan" of more than 80 chemicals for risk assessment and risk reduction. Another proposed rule that EPA withdrew would have limited industry's claims of confidential business information (CBI) for the health and safety studies needed, when new chemicals are submitted under TSCA for review. The EPA said it continued "to try to reduce unwarranted claims of confidentiality and has taken a number of significant steps that have had dramatic results... tightening policies for CBI claims and declassifying unwarranted confidentiality claims, challenging companies to review existing CBI claims to ensure that they are still valid and providing easier and enhanced access to a wider array of information."

The chemical industry group American Chemistry Council commended EPA for "choosing a course of action that will ultimately strengthen the performance of the nation's primary chemical management law." Richard Denison, senior scientist with the Environmental Defense Fund, commented "both rules were subject to intense opposition and lobbying from the chemical industry" and "Faced presumably with the reality that was never going to let EPA even propose the rules for public comment, EPA decided to withdraw them."

On 29 January 2014 EPA released a final alternatives assessment for BPA in thermal paper as part of its Design for the Environment program.

Chemical manufacturers reactions to bans

In March 2009 the six largest US producers of baby bottles decided to stop using bisphenol A in their products. The same month Sunoco, a producer of gasoline and chemicals, refused to sell BPA to companies for use in food and water containers for children younger than 3, saying it could not be certain of the compound's safety. In May 2009, Lyndsey Layton from the Washington Post accused manufacturers of food and beverage containers and some of their biggest customers of the public relations and lobbying strategy to block government BPA bans. She noted that, "Despite more than 100 published studies by government scientists and university laboratories that have raised health concerns about the chemical, the Food and Drug Administration has deemed it safe largely because of two studies, both funded by a chemical industry trade group". In August 2009 the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel investigative series into BPA and its effects showed the Society of the Plastics Industry plans of a major public relations blitz to promote BPA, including plans to attack and discredit those who report or comment negatively on BPA and its effects.

BPA free, unknown substitute

The chemical industry over time responded to criticism of BPA by promoting "BPA-free" products. For example, in 2010, General Mills announced it had found a "BPA-free alternative" can liner that works with tomatoes. It said it would begin using the BPA-free alternative in tomato products sold by its organic foods subsidiary Muir Glen with that year's tomato harvest. As of 2014, General Mills has refused to state which alternative chemical it uses, and whether it uses it on any of its other canned products.

BPA free, epoxyfree

A minority of companies have stated what alternative compound(s) they use. Following an inquiry by Representative Edward Markey (D-Mass) seventeen companies replied, xxx said they were going BPA-free. None of the companies said they are or were going to use Bisphenol S; only four stated the alternative to BPA that they will be using. ConAgra stated in 2013 "alternate liners for tomatoes are vinyl...New aerosol cans are lined with polyester resin", Eden Foods stated that only their "beans are canned with a liner of an "oleoresinous c-enamel that does not contain the endocrine disruptor BPA. Oleoresin is a mixture of oil and resin extracted from plants such as pine or balsam fir", Hain Celestial Group will use "modified polyester and/ or acrylic … by June 2014 for our canned soups, beans, and vegetables", Heinz stated in 2011 it "intend to replace epoxy linings in all our food containers…. We have prioritized baby foods", and in 2012 "no BPA in any plastic containers we use".

BPA substitute BPS

Some "BPA free" plastics are made from epoxy containing a compound called bisphenol S (BPS). BPS shares a similar structure and versatility to BPA and has been used in numerous products from currency to thermal receipt paper. Widespread human exposure to BPS was confirmed in an analysis of urine samples taken in the U.S., Japan, China, and five other Asian countries. Researchers found BPS in all the receipt paper, 87 percent of the paper currency and 52 percent of recycled paper they tested. The study found that people may be absorbing 19 times more BPS through their skin than the amount of BPA they absorbed, when it was more widely used. In a 2011 study researchers looked at 455 common plastic products and found that 70% tested positive for estrogenic activity. After the products had been washed or microwaved the proportion rose to 95%. The study concluded: "Almost all commercially available plastic products we sampled, independent of the type of resin, product, or retail source, leached chemicals having reliably-detectable EA , including those advertised as BPA-free. In some cases, BPA-free products released chemicals having more EA than BPA-containing products." A systematic review published in 2015 found that "based on the current literature, BPS and BPF are as hormonally active as BPA, and have endocrine disrupting effects."

Phenol-based substitutes

Among potential substitutes for BPA, phenol-based chemicals closely related to BPA have been identified. The non-extensive list includes bisphenol E (BPE), bisphenols B (BPB), 4-cumylphenol (HPP) and bisphenol F (BPF), with only BPS being currently used as main substitute in thermal paper.

Bioremediation

Microbial degradation

Two enzymes participate in bisphenol degradation:

- The enzyme 2,4'-dihydroxyacetophenone dioxygenase, which can be found in Alcaligenes sp, transforms 2,4'-dihydroxyacetophenone and O2 into 4-hydroxybenzoate and formate.

- The enzyme 4-hydroxyacetophenone monooxygenase, which can be found in Pseudomonas fluorescens, uses (4-hydroxyphenyl)ethan-1-one, NADPH, H and O2 to produce 4-hydroxyphenyl acetate, NADP, and H2O.

The fungus Cunninghamella elegans is also able to degrade synthetic phenolic compounds like bisphenol A.

Plant degradation

Portulaca oleracea efficiently removes bisphenol A from a hydroponic solution. How this happens is unclear.

References

- "Chemical Fact Sheet – Cas #80057 CASRN 80-05-7". speclab.com. 1 April 2012.

- ^ Pivnenko, K.; Pedersen, G. A.; Eriksson, E.; Astrup, T. F. (1 October 2015). "Bisphenol A and its structural analogues in household waste paper". Waste Management. 44: 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2015.07.017. PMID 26194879.

- ^ http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/francais/videos/2015/septembre/affaire-n-2015-480-qpc.144326.html

- "FDA Regulations No Longer Authorize the Use of BPA in Infant Formula Packaging Based on Abandonment; Decision Not Based on Safety". Fda.gov. 12 July 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- "Bisphenol A (BPA): Use in Food Contact Application". fda.gov.

- ^ "Bisphenol A". European Food Safety Authority. 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ "Current SVHC Intentions – Bisphenol A".

- ^ Fiege H; Voges H-W; Hamamoto T; Umemura S; = Iwata T; Miki H; Fujita Y; Buysch H-J; = Garbe D; Paulus W (2002). Phenol Derivatives. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_313.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - "Experts demand European action on plastics chemical". Reuters. 22 June 2010.

- ^ "CERHR Expert Panel Report for Bisphenol A" (PDF). September 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Bisphenol A Action Plan" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ "Concern over canned foods". Consumer Reports. December 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- "Soaring BPA Levels Found in People Who Eat Canned Foods". Fox News Channel. 23 November 2011.

- А. П. Дианин (A. P. Dianin) (1891). "О продуктах конденсации кетонов с фенолами". Журнал Русского Физико-Химического Общества (Journal of the Russian Physical-Chemical Society). 23: 488–517, 523–546, 601–611.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) See especially p. 492. - Zincke, T. (1905). "Ueber die Einwirkung von Brom und von Chlor auf Phenole: Substitutionsprodukte, Pseudobromide und Pseudochloride". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 343: 75–99. doi:10.1002/jlac.19053430106.

- Uglea, Constantin V.; Negulescu, Ioan I. (1991). Synthesis and Characterization of Oligomers. CRC Press. p. 103. ISBN 0-8493-4954-0.

- "Bisphenol A Information Sheet" (PDF). Bisphenol A Global Industry Group. October 2002. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Studies Report More Harmful Effects From BPA". U.S. News & World Report. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- Replogle J (17 July 2009). "Lawmakers to press for BPA regulation". California Progress Report. Archived from the original on 22 July 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Ubelacker, Sheryl (16 April 2008). "Ridding life of bisphenol A a challenge". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- Kroschwitz, Jacqueline I. Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology. Vol. 5 (5 ed.). p. 8. ISBN 0-471-52695-9.

- "Polycarbonate (PC) Polymer Resin". Alliance Polymers, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 September 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Wittcoff, Harold; Reuben, B. G.; Plotkin, Jeffrey S. (2004). Industrial Organic Chemicals. Wiley-IEEE. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-471-44385-8. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Erickson BE (2 June 2008). "Bisphenol A under scrutiny". Chemical and Engineering News. 86 (22). American Chemical Society: 36–39. doi:10.1021/cen-v086n022.p036.

- Byrne, Jane (22 September 2008). "Consumers fear the packaging – a BPA alternative is needed now". Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- "Bisphenol A". Pesticideinfo.org. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- US 6562755, "Thermal paper with security features"

- Raloff, Janet (7 October 2009). "Concerned about BPA: Check your receipts". Science News. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Safer Choice" (PDF). epa.gov.

- Pivnenko, Kostyantyn; Laner, David; Astrup, Thomas F. (15 November 2016). "Material Cycles and Chemicals: Dynamic Material Flow Analysis of Contaminants in Paper Recycling". Environmental Science & Technology. 50 (22): 12302–12311. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b01791. ISSN 0013-936X.

- Marciano MA, Ordinola-Zapata R, Cunha TV, Duarte MA, Cavenago BC, Garcia RB, Bramante CM, Bernardineli N, Moraes IG (April 2011). "Analysis of four gutta-percha techniques used to fill mesial root canals of mandibular molars". International Endodontic Journal. 44 (4): 321–329. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01832.x. PMID 21219361.

- "Bisphenol A (BPA) Information for Parents". Hhs.gov. 15 January 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Biello D (19 February 2008). "Plastic (not) fantastic: Food containers leach a potentially harmful chemical". Scientific American. 2. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- See:

- А. Дианина (1891) "О продуктахъ конденсацiи кетоновъ съ фенолами" (On condensation products of ketones with phenols), Журнал Русского физико-химического общества (Journal of the Russian Physical Chemistry Society), 23 : 488-517, 523–546, 601–611 ; see especially pages 491-493 ("Диметилдифеиолметаиь" (dimethyldiphenolmethane)).

- Reprinted in condensed form in: A. Dianin (1892) "Condensationsproducte aus Ketonen und Phenolen" (Condensation products of ketones and phenols), Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin, 25, part 3 : 334-337.

- Heather Caliendo for PlasticsToday – Packaging Digest, June 20, 2012 History of BPA Archived 12 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Walsh B (1 April 2010). "The Perils of Plastic – Environmental Toxins – TIME". Time. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Vogel SA (2009). "The Politics of Plastics: The Making and Unmaking of Bisphenol A "Safety". Am J Public Health. 99 (S3): S559 – S566. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.159228. PMC 2774166. PMID 19890158.

- Dodds EC, Lawson W (1936). "Synthetic Œstrogenic Agents without the Phenanthrene Nucleus". Nature. 137 (3476): 996. Bibcode:1936Natur.137..996D. doi:10.1038/137996a0.

- ^ Dodds E. C.; Lawson W. "Molecular Structure in Relation to Oestrogenic Activity. Compounds without a Phenanthrene Nucleus". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 125 (839): 222–232. doi:10.1098/rspb.1938.0023.

- ^ Hejmej, Anna; Kotula-Balak, Magorzata; Bilinsk, Barbara (2011). "Antiandrogenic and Estrogenic Compounds: Effect on Development and Function of Male Reproductive System". Steroids – Clinical Aspect. doi:10.5772/28538.

- Kwon J.H.; Katz L.E.; Liljestrand H.M. (2007). "Modeling binding equilibrium in a competitive estrogen receptor binding assay". Chemosphere. 69 (7): 1025–1031. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.04.047. PMID 17559906.

- Ahmed, R. A. M. (2014). "Effect of prenatal exposure to Bisphenol A on the vagina of albino rats: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study". Folia Morphologica. 73: 399–408. doi:10.5603/FM.2014.0061.

- Ramos, J.G. (2003). "Bisphenol A induces both transient and permanent histofunctional alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in prenatally exposed male rats". Endocrinology. 144: 3206–3215. doi:10.1210/en.2002-0198. PMID 12810577.

- ^ Takeda Y.; Liu X.; Sumiyoshi M.; Matsushima A.; Shimohigashi M.; Shimohigashi Y. (July 2009). "Placenta expressing the greatest quantity of bisphenol A receptor ERR{gamma} among the human reproductive tissues: Predominant expression of type-1 ERRgamma isoform". J. Biochem. 146 (1): 113–22. doi:10.1093/jb/mvp049. PMID 19304792.

- ^ Matsushima A, Kakuta Y, Teramoto T, Koshiba T, Liu X, Okada H, Tokunaga T, Kawabata S, Kimura M, Shimohigashi Y (October 2007). "Structural evidence for endocrine disruptor bisphenol A binding to human nuclear receptor ERR gamma". J. Biochem. 142 (4): 517–24. doi:10.1093/jb/mvm158. PMID 17761695.

- Prossnitz, Eric R.; Barton, Matthias (2014). "Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 389 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. ISSN 0303-7207. PMC 4040308. PMID 24530924.

- "MSC unanimously agrees that Bisphenol A is an endocrine disruptor - All news - ECHA". echa.europa.eu. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Mirmira, P; Evans-Molina, C. "Bisphenol A, obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: genuine concern or unnecessary preoccupation?". Translational research: the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine (Review). 164 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.003. PMC 4058392. PMID 24686036.

- "FDA to Ban BPA from Baby Bottles; Plan Falls Short of Needed Protections: Scientists". Common Dreams.