This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 81.1.71.31 (talk) at 13:49, 7 March 2007 (deleted "IT"S DELICIOUSFUL!!!!!!"). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:49, 7 March 2007 by 81.1.71.31 (talk) (deleted "IT"S DELICIOUSFUL!!!!!!")(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see LSD (disambiguation). Pharmaceutical compound | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | LSD, LSD-25, lysergide, d-lysergic acid diethylamide, N,N-diethyl-d-lysergamide |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, Intravenous, Transdermal |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3 hours |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.031 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

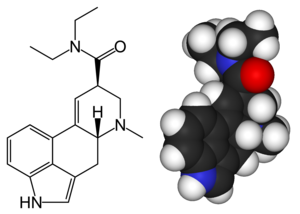

| Formula | C20H25N3O |

| Molar mass | 323.43 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 80 °C (176 °F) |

SMILES

| |

Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly called LSD, LSD-25, or acid, is a semisynthetic psychedelic drug, synthesized from lysergic acid derived from ergot, a grain fungus that typically grows on rye. The short form LSD comes from the German LSDM, "Lyserg säure-diethylamid".

LSD is sensitive to oxygen, ultraviolet light, and chlorine, especially in solution (though its potency may last years if it is stored away from light and moisture at low temperature). In pure form it is colorless, odorless and mildly bitter. LSD is typically delivered orally, usually on a substrate such as absorbent blotter paper, a sugar cube, or gelatin. In its liquid form, it can be administered by intramuscular or intravenous injection, or even in the form of eye-drops. In its blotter paper form, it is popularly taken by placing a "tab" in the user's mouth for several minutes. The threshold dosage level for an effect on humans is of the order of 20 to 30 micrograms.

Introduced by Sandoz Laboratories as a drug with various psychiatric uses, LSD quickly became a therapeutic agent that appeared to show great promise. However, the extra-medical use of the drug in Western society in the middle years of the twentieth century led to a political firestorm that resulted in the banning of the substance for medical as well as recreational and spiritual uses. Despite this, it is still considered a promising drug in some intellectual circles, and organizations such as MAPS, Heffter Research Institute and the Albert Hofmann Foundation exist to fund, encourage and coordinate research into its medical uses.

Origins and history

LSD was first synthesized on April 7, 1938 by Swiss chemist Dr. Albert Hofmann at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, as part of a large research program searching for medically useful ergot alkaloid derivatives. Its psychedelic properties were unknown until 5 years later, when Hofmann, acting on what he has called a "peculiar presentiment," returned to work on the chemical. He attributed the discovery of the compound's psychoactive effects to the accidental absorption of a tiny amount through his skin on April 16, which led to him testing a larger amount (250 µg) on himself for psychoactivity on April 19.

Until 1966, LSD and psilocybin were provided by Sandoz Laboratories free of charge to interested scientists under the trade name "Delysid". The use of these compounds by psychiatrists to gain a better subjective understanding of the schizophrenic experience was an accepted practice. Many clinical trials were conducted on the potential use of LSD in psychedelic psychotherapy, generally with very positive results.

Regulation and research

Cold War intelligence services were keenly interested in the possibilities of using LSD for interrogation and mind control, and also for large-scale social engineering. The CIA conducted extensive research on LSD, which was mostly destroyed. LSD was a central research area for Project MKULTRA, the code name for a CIA mind-control research program begun in the 1950s and continued until the late 1960s. Tests were also conducted by the U.S. Army Biomedical Laboratory (now known as the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense) located in the Edgewood Arsenal at Aberdeen Proving Grounds. Volunteers would take LSD and then perform a battery of tests to investigate the effects of the drug on soldiers. Based on remaining publicly available records, the projects seem to have concluded that LSD was of little practical use as a mind control drug and moved on to other drugs. Both the CIA and the Army experiments became highly controversial when they became public knowledge in the 1970s, as the test subjects were not normally informed of the nature of the experiments, or even that they were subjects in experiments at all. Several subjects developed severe mental illnesses and even committed suicide after the experiments. The controversy contributed to President Ford's creation of the Rockefeller Commission and new regulations on informed consent.

The British government also engaged in LSD testing; in 1953 and 1954, scientists working for MI6 dosed servicemen in an effort to find a "truth drug". The test subjects were not informed that they were being given LSD, and had in fact been told that they were participating in a medical project to find a cure for the common cold. One subject, aged 19 at the time, reported seeing "walls melting, cracks appearing in people's faces … eyes would run down cheeks, Salvador Dalí-type faces … a flower would turn into a slug". After keeping the trials secret for many years, MI6 agreed in 2006 to pay the former test subjects financial compensation. Like the CIA, MI6 decided that LSD was not a practical drug for mind control purposes.

LSD first became popular recreationally among a small group of mental health professionals such as psychiatrists and psychologists during the 1950s, as well as by socially prominent and politically powerful individuals such as Henry and Clare Boothe Luce to whom the early LSD researchers were connected socially.

Several mental health professionals involved in LSD research, most notably Harvard psychology professors Dr. Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, became convinced of LSD's potential as a tool for spiritual growth. In 1961, Dr. Timothy Leary received grant money from Harvard University to study the effects of LSD on test subjects. 3,500 doses were given to over 400 people. Of those tested, 90% said they would like to repeat the experience, 83% said they had "learned something or had insight," and 62% said it had changed their life for the better.

Their research became more esoteric and controversial, as Leary and Alpert alleged links between the LSD experience and the state of enlightenment sought after in many mystical traditions. They were dismissed from the traditional academic psychology community, and as such cut off from legal scientific acquisition of the drug. Drs. Leary and Alpert somehow acquired a quantity of LSD and relocated to a private mansion, where they continued their research. The experiments lost their scientific character as the pair evolved into countercultural spiritual gurus associated with the hippie movement, encouraging people to question authority and challenge the status quo, a concept summarized in Leary's catchphrase, "Turn on, tune in, drop out".

The drug was banned in the United States in 1967, with scientific therapeutic research as well as individual research also becoming prohibitively difficult. Many other countries, under pressure from the U.S., quickly followed suit. Since 1967, underground recreational and therapeutic LSD use has continued in many countries, supported by a black market and popular demand for the drug. Legal, academic research experiments on the effects and mechanisms of LSD are also conducted on occasion, but rarely involve human subjects. Despite its proscription, the hippie counterculture continued to promote the regular use of LSD, led by figures such as Leary and psychedelic rock bands such as The Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd.

Acidhead has been used as a term (often derogatory) for one who frequently uses LSD.

According to Leigh Henderson and William Glass, two researchers associated with the NIDA who performed a 1994 review of the literature, LSD use is relatively uncommon when compared to the abuse of alcohol, cocaine, and prescription drugs. Over the previous fifteen years, long-term usage trends stayed fairly stable, with roughly 5% of the population using the drug and most users being in the 16 to 23 age range. Henderson and Glass found that LSD users typically partook of the substance on an infrequent, episodic basis, then "maturing out" after two to four years. Overall, LSD appeared to have comparatively few adverse health consequences, of which "bad trips" were the most commonly reported (and, the researchers found, one of the chief reasons youths stop using the drug).

Dosage

LSD is, by mass, one of the most potent drugs yet discovered. Dosages of LSD are measured in micrograms (µg), or millionths of a gram. By comparison, dosages of almost all other drugs, both recreational and medical, are measured in milligrams (mg), or thousandths of a gram. Hofmann determined that an active dose of mescaline, roughly 0.2 to 0.5 g, has effects comparable to 100 µg or less of LSD; put another way, LSD is between five and ten thousand times more active than mescaline.

While a typical single dose of LSD may be between 100 and 500 micrograms — an amount roughly equal to one-tenth the mass of a grain of sand — threshold effects can be felt with as little as 20 micrograms.

According to Stoll, the dosage level that will produce a threshold hallucinogenic effect in humans is generally considered to be 20 to 30 μg, with the drug's effects becoming markedly more evident at higher dosages. According to Glass and Henderson's review, black-market LSD is largely unadulterated though sometimes contaminated by manufacturing by-products. Typical doses in the 1960s ranged from 200 to 1000 µg, while street samples of the 1970s contained 30 to 300 µg. By the mid-1980s, the average had reduced to about 100 to 125 µg, lowering still further in the 1990s to the 20–80 µg range. (Lower doses, Glass and Henderson found, generally produce fewer bad trips.) Dosages by frequent users can be as high as 1,200 µg (1.2 mg), although such a high dosage may precipitate unpleasant physical and psychological reactions.

Estimates for the lethal dosage (LD50) of LSD range from 200 μg/kg to more than 1 mg/kg of human body mass, though most sources report that there are no known human cases of such an overdose. Other sources note one report of a suspected fatal overdose of LSD occuring in 1974 in Kentucky in which there were indications that ~1/3 of a gram (320 mg or 320,000 µg) had been injected intravenously, i.e., over 3,000 more typical oral doses of ~100 µg had been injected.

LSD is not considered addictive, in that its users do not exhibit the medical community's commonly accepted definitions of addiction and physical dependence. Rapid tolerance build-up prevents regular use, and there is cross-tolerance shown between LSD, mescaline and psilocybin. This tolerance diminishes after a few days' abstention from use.

Chemistry

LSD is an example of an ergoline derivative. It is commonly produced from lysergic acid, which is made from ergotamine, a substance derived from the ergot fungus on rye, or from ergine (lysergic acid amide). LSA, lysergic acid amide, is the sister chemical of LSD found in morning glory and hawaiian baby woodrose seeds. It is theoretically possible to manufacture LSD from morning glory or hawaiian baby woodrose seed. LSD is a chiral compound with two stereocenters at the carbon atoms C-5 and C-8, so that theoretically four different optical isomers of LSD could exist. LSD, also called (+)-D-LSD, has the absolute configuration (5R,8R). The C-5 isomers of lysergamides do not exist in nature and are not formed during the synthesis from D-lysergic acid. However, LSD and iso-LSD, the two C-8 isomers, rapidly interconvert in the presence of base. Non-psychoactive iso-LSD which has formed during the synthesis can be removed by chromatography and can be isomerized to LSD.

Stability

"LSD," writes the chemist Alexander Shulgin, "is an unusually fragile molecule." It is stable for indefinite amounts of time if stored, as a salt or in water, at low temperature and protected from air and light exposure. Two portions of its molecular structure are particularly sensitive, the carboxamide attachment at the 8-position and the double bond between the 8-position and the aromatic ring. The former is affected by high pH, and if perturbed will produce isolysergic acid diethylamide (iso-LSD), which is biologically inactive. If water or alcohol adds to the double bond (especially in the presence of light), LSD converts to "lumi-LSD", which is totally inactive in human beings, to the best of current knowledge. Furthermore, chlorine destroys LSD molecules on contact; even though chlorinated tap water typically contains only a slight amount of chlorine, because a typical LSD solution only contains a small amount of LSD, dissolving LSD in tap water is likely to completely eliminate the substance.

A controlled study was undertaken to determine the stability of LSD in pooled urine samples. The concentrations of LSD in urine samples were followed over time at various temperatures, in different types of storage containers, at various exposures to different wavelengths of light, and at varying pH values. These studies demonstrated no significant loss in LSD concentration at 25 degrees C for up to 4 weeks. After 4 weeks of incubation, a 30% loss in LSD concentration at 37 degrees C and up to a 40% at 45 degrees C were observed. Urine fortified with LSD and stored in amber glass or nontransparent polyethylene containers showed no change in concentration under any light conditions. Stability of LSD in transparent containers under light was dependent on the distance between the light source and the samples, the wavelength of light, exposure time, and the intensity of light. After prolonged exposure to heat in alkaline pH conditions, 10 to 15% of the parent LSD epimerized to iso-LSD. Under acidic conditions, less than 5% of the LSD was converted to iso-LSD. It was also demonstrated that trace amounts of metal ions in buffer or urine could catalyze the decomposition of LSD and that this process can be avoided by the addition of EDTA.

Production

Because an active dose of LSD is astonishingly minute, a large number of doses can be synthesized from a comparatively small amount of raw material. Beginning with ergotamine tartrate, for example, one can manufacture roughly one kilogram of pure, crystalline LSD from five kilograms of tartrate. Five kilograms of LSD — 25 kilograms of ergotamine tartrate — could provide 100 million "hits", sufficient for supplying the entire illicit demand of the United States. Since the masses involved are so small, concealing and transporting illicit LSD is much easier than smuggling other illegal drugs (say, cocaine or cannabis) in equal dosage quantities.

Manufacturing LSD requires laboratory equipment and experience in the field of organic chemistry. It takes two or three days to produce 30 to 100 grams of pure compound. It is believed that LSD usually is not produced in large quantities, but rather in a series of small batches. This technique minimizes the loss of precursor chemicals in case a synthesis step does not work as expected.

Forms of LSD

LSD is produced in crystalline form and then mixed with excipients or redissolved for production in ingestible forms. Liquid solution is either distributed as-is in small vials or, more commonly, sprayed onto or soaked into a distribution medium. Historically, LSD solutions were first sold on sugar cubes, but practical considerations forced a change to tablet form. Early pills or tabs were flattened on both ends and identified by color: "grey flat", "blue flat", and so forth. Next came "domes", which were rounded on one end, then "double domes" rounded on both ends, and finally small tablets known as "microdots". Later still, LSD began to be distributed in thin squares of gelatin ("window panes", "gel tabs") and, most commonly, as blotter paper: sheets of paper impregnated with LSD and perforated into small squares of individual dosage units. The paper is then cut into small square pieces called "tabs" or "hits" for distribution. Individual producers often print designs onto the paper serving to identify different makers, batches or strengths, and such "blotter art" often emphasizes psychedelic themes.

LSD has been sold under a wide variety of street names including Acid, Trips, Alice Dee, 'Cid/Sid, Barrels, Blotter, Doses, Fry, "L", Liquid, Liquid A, Lucy, Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, Microdots, Mind detergent, Orange cubes, Orange micro, Owsley, Hits, Paper acid, Sacrament, Sandoz, Sugar, Sugar lumps, Sunshine, Tabs, Ticket, Twenty-five, Wedding bells, Windowpane, etc., as well as names that reflect the designs on the sheets of blotter paper. On occasion, authorities have encountered the drug in other forms — including powder or crystal, and capsule. More than 200 types of LSD tablets have been encountered since 1969 and more than 350 paper designs have been observed since 1975. Designs range from simple five-point stars in black and white to exotic artwork in full four-color print.

Legal status

The United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances (adopted in 1971) requires its parties to prohibit LSD. Hence, it is illegal in all parties to the convention, which includes the United States, Australia, and most of Europe. However, enforcement of extant laws varies from country to country.

LSD is easy to conceal and smuggle. A tiny vial can contain thousands of doses. Not much money is made from retail-level sales of LSD, so the drug is typically not associated with the violent organized criminal organizations involved in cocaine and opiate smuggling.

Canada

In Canada, LSD is a controlled substance under Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). Every person who seeks to obtain the substance without disclosing authorization to obtain such substances 30 days prior to obtaining another prescription from a practitioner is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 3 years. Possession for purpose of trafficking is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for 10 years.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, Lysergide and derivatives are regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance, and can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purposes. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without presciption can be fined $10000(HKD). The penalty for trafficking or illegally manufacturing the substance is a $5,000,000 (HKD) fine and life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000 (HKD) fine and/or 7 years' imprisonment.

United States: Prior to 1967

Further information: ]Beginning in the 1950's the Central Intelligence Agency began a research program code named Project MKULTRA. Experiments included administering LSD to CIA employees, military personnel, doctors, other government agents, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and members of the general public in order to study their reactions, usually without the subject's knowledge. The project was revealed in the US congressional Rockefeller Commission report.

Prior to October 6th, 1966, LSD was available legally in the United States as an experimental psychiatric drug. (LSD "apostle" Al Hubbard actively promoted the drug between the 1950s and the 1970s and introduced thousands of people to it.) The US Federal Government classified it as a Schedule I drug according to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. As such, the Drug Enforcement Administration holds that LSD meets the following three criteria: it is deemed to have a high potential for abuse; it has no legitimate medical use in treatment; and there is a lack of accepted safety for its use under medical supervision. (LSD prohibition does not make an exception for religious use.) Lysergic acid and lysergic acid amide, LSD precursors, are both classified in Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act. Ergotamine tartrate, a precursor to lysergic acid, is regulated under the Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act.

LSD has been manufactured illegally since the 1960s. Historically, LSD was distributed not for profit, but because those who made and distributed it truly believed that the psychedelic experience could do good for humanity, that it expanded the mind and could bring understanding and love. A limited number of chemists, probably fewer than a dozen, are believed to have manufactured nearly all of the illicit LSD available in the United States. The best known of these is undoubtedly Augustus Owsley Stanley III, usually known simply as Owsley. The former chemistry student set up a private LSD lab in the mid-Sixties in San Francisco and supplied the LSD consumed at the famous Merry Pranksters parties held by Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, and other major events such as the Gathering of the tribes in San Francisco in January 1967. He also had close social connections to leading San Francisco bands the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother and The Holding Company, regularly supplied them with his LSD and also worked as their live sound engineer and made many tapes of these groups in concert. Owsley's LSD activities — immortalized by Steely Dan in their song "Kid Charlemagne" — ended with his arrest at the end of 1967, but some other manufacturers probably operated continuously for 30 years or more. Announcing Owsley's first bust in 1966, The San Francisco Chronicle's headline "LSD Millionaire Arrested" inspired the rare Grateful Dead song "Alice D. Millionaire."

United States: 1970 to the present

American LSD usage declined in the 1970s and 1980s, then experienced a mild resurgence in popularity in the 1990s. Although there were many distribution channels during this decade, the U.S. DEA identified continued tours by the psychedelic rock band The Grateful Dead and the then-burgeoning rave scene as primary venues for LSD trafficking and consumption. American LSD usage fell sharply circa 2000. The decline is attributed to the arrest of two chemists, William Leonard Pickard, a Harvard-educated organic chemist, and Clyde Apperson. According to DEA reports, black market LSD availability dropped by 95% after the two were arrested in 2000. These arrests were a result of the largest LSD manufacturing raid in DEA history.

Pickard was an alleged member of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love group that produced and sold LSD in California during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is believed he had links to other "cooks" associated with this group — an original source of the drug back in the 1960s — and his arrest may have forced other operations to cease production, leading to the large decline in street availability.

The DEA claims these two individuals were responsible for the vast majority of LSD sold illegally in the United States and a significant amount of the LSD sold in Europe, and that they worked closely with organized traffickers. While this claim may have some bearing, the extent of Pickard's direct influence on the overall availability in the United States is not fully known. Some attest that "Pickard's Acid" was sold exclusively in Europe, and was not distributed through American music venues.

In November of 2003, Pickard was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole, and Apperson was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment without parole, after being convicted in Federal Court of running a large scale LSD manufacturing operation out of several clandestine laboratories, including a former missile silo near Wamego, Kansas.

LSD manufacturers and traffickers can be categorized into two groups: A few large scale producers, such as the aforementioned Pickard and Apperson, and an equally limited number of small, clandestine chemists, consisting of independent producers who, operating on a comparatively limited scale, can be found throughout the country. As a group, independent producers are of less concern to the Drug Enforcement Administration than the larger groups, as their product reaches only local markets.

See also

- ALD-52

- Bogle-Chandler case, deaths mistakenly attributed to LSD overdoses

- Drug urban legends

- Entheogen

- List of notable psychedelic self-experimenters

- Project MKULTRA, Central Intelligence Agency mind-control research program that began in the 1950s.

- Psychedelics in popular culture

- Psychedelic psychotherapy

- United States v. Stanley, US Supreme Court case

- Related chemical compounds: ergolines, LSA, psilocybin, DMT, serotonin

References

- ^ Hofmann, Albert. LSD—My Problem Child (McGraw-Hill, 1980). ISBN 0-07-029325-2. Available online here or here; accessed 2007-02-01.

- ACHRE Report, chapter 3: "Supreme Court Dissents Invoke the Nuremberg Code: CIA and DOD Human Subjects Research Scandals".

- Rob Evans, "MI6 pays out over secret LSD mind control tests". The Guardian 24 February 2006.

- Goldsmith, Neal M. (1995). "A Review of "LSD : Still With Us After All These Years"". Newsletter of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 6 (1). Retrieved 2006-01-31.

- ^ Henderson, Leigh A.; Glass, William J. (1994). LSD: Still with Us after All These Years. ISBN 978-0787943790.

{{cite book}}: Text "Jossey-Bass Inc., San Francisco" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greiner T, Burch NR, Edelberg R (1958). "Psychopathology and psychophysiology of minimal LSD-25 dosage; a preliminary dosage-response spectrum". AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 79 (2): 208–10. PMID 13497365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stoll, W.A. (1947). Ein neues, in sehr kleinen Mengen wirsames Phantastikum. Schweiz. Arch. Neur. 60,483.

- "LSD Vault: Dosage". Erowid. 2006-07-06. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

tihkalwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Li Z., McNally A. J., Wang H., Salamone S. J. (1998). "Stability study of LSD under various storage conditions". J Anal Toxicol. 22 (6): 520–5. PMID 9788528.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "LSD in the US – Manufacture", DEA Publications.

- Honig, David. Frequently Asked Questions via Erowid.

- "Street Terms: Drugs and the Drug Trade". Office of National Drug Control Policy. 2005-04-05. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Seper, Jerry. "Man sentenced to life in prison as dealer of LSD". The Washington Times 27 November 2003.

Further reading

- Aldous FAB, Barrass BC, Brewster K, et al. "Structure-Activity Relationships in Psychotomimetic Phenylalkylamines," Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 17, 1100–1111 (1974)

- Grof, Stanislave. LSD Psychotherapy. (April 10, 2001)

- Lee, Martin A. and Bruce Shlain. Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond

External links

- Belfast Telegraph Dr. Albert Hofmann - The father of LSD

- Salon.com: Dr. Hofmann's problem child turns 58, April 16, 2001

- "Spontaneous pattern formation in large scale brain activity: what visual migraines and hallucinations tell us about the brain", lecture by Jack Cowan (via the Internet Archive)

- "Hofmann's Potion: The Early Years of LSD" by the National Film Board of Canada

- Erowid -> LSD Information

- A Critical Review of Theories and Research Concerning LSD and Mental Health

- The Neurochemistry of Psychedelic Experience, Science & Consciousness Review

- Current LSD Research – MAPS

- International 3 day conference on LSD in Basel

- The Lycaeum Archive -> LSD

- FRANK - LSD