Pharmaceutical compound

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| Addiction liability | High |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | GABA analogue, GHB receptor agonists—GABA receptor agonist; Psycholeptic;

Depressant; Hypnotic Sedative |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25% (oral) |

| Metabolism | 95–98%, mainly liver, also in blood and tissues |

| Onset of action | Within 5–15 minutes |

| Elimination half-life | 30–60 minutes |

| Excretion | 1–5%, kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.218.519 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

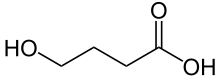

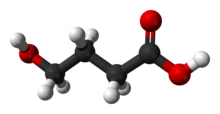

| Formula | C4H8O3 |

| Molar mass | 104.105 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

γ-Hydroxybutyric acid, also known as gamma-hydroxybutyric acid, GHB, or 4-hydroxybutanoic acid, is a naturally occurring neurotransmitter and a depressant drug. It is a precursor to GABA, glutamate, and glycine in certain brain areas. It acts on the GHB receptor and is a weak agonist at the GABAB receptor. GHB has been used in the medical setting as a general anesthetic and as treatment for cataplexy, narcolepsy, and alcoholism. The substance is also used illicitly for various reasons, including as a performance-enhancing drug, date rape drug, and as a recreational drug.

It is commonly used in the form of a salt, such as sodium γ-hydroxybutyrate (NaGHB, sodium oxybate, or Xyrem) or potassium γ-hydroxybutyrate (KGHB, potassium oxybate). GHB is also produced as a result of fermentation, and is found in small quantities in some beers and wines, beef, and small citrus fruits.

Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency is a disease that causes GHB to accumulate in the blood.

Medical use

Main article: Sodium oxybateGHB is used for medical purposes in the treatment of narcolepsy and, more rarely, alcohol dependence, although there remains uncertainty about its efficacy relative to other pharmacotherapies for alcohol dependence. The authors of a 2010 Cochrane review concluded that "GHB appears better than NTX and disulfiram in maintaining abstinence and preventing craving in the medium term (3 to 12 months)". It is sometimes used off-label for the treatment of fibromyalgia. GHB is the active ingredient of the prescription medication sodium oxybate (Xyrem). Sodium oxybate is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of cataplexy associated with narcolepsy and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) associated with narcolepsy.

GHB has been shown to reliably increase slow-wave sleep and decrease the tendency for REM sleep in modified multiple sleep latency tests.

The FDA-approved labeling for sodium oxybate suggests no evidence GHB has teratogenic, carcinogenic or hepatotoxic properties. Its favorable safety profile relative to ethanol may explain why GHB continues to be investigated as a candidate for alcohol substitution.

Recreational use

GHB is a central nervous system depressant used as an intoxicant. It has many street names. Its effects have been described as comparable with ethanol (alcohol) and MDMA use, such as euphoria, disinhibition, enhanced libido and empathogenic states. A review comparing ethanol to GHB concluded that the dangers of the two drugs were similar. At higher doses, GHB may induce nausea, dizziness, drowsiness, agitation, visual disturbances, depressed breathing, amnesia, unconsciousness, and death. One potential cause of death from GHB consumption is polydrug toxicity. Co-administration with other CNS depressants such as alcohol or benzodiazepines can result in an additive effect (potentiation), as they all bind to gamma-aminobutyric acid (or "GABA") receptor sites. The effects of GHB can last from 1.5 to 4 hours, or longer if large doses have been consumed. Consuming GHB with alcohol can cause respiratory arrest and vomiting in combination with unarousable sleep, which can lead to death.

Recreational doses of 1–2 g generally provide a feeling of euphoria, and larger doses create deleterious effects such as reduced motor function and drowsiness. The sodium salt of GHB has a salty taste. Other salt forms such as calcium GHB and magnesium GHB have also been reported, but the sodium salt is by far the most common.

Some prodrugs, such as γ-butyrolactone (GBL), convert to GHB in the stomach and bloodstream. Other prodrugs exist, such as 1,4-butanediol (1,4-B). GBL and 1,4-B are normally found as pure liquids, but they can be mixed with other more harmful solvents when intended for industrial use (e.g. as paint stripper or varnish thinner).

GHB can be manufactured with little knowledge of chemistry, as it involves the mixing of its two precursors, GBL and an alkali hydroxide such as sodium hydroxide, to form the GHB salt. Due to the ease of manufacture and the availability of its precursors, it is not usually produced in illicit laboratories like other synthetic drugs, but in private homes by low-level producers.

GHB is colourless and odourless.

Party use

GHB has been used as a club drug, apparently starting in the 1990s, as small doses of GHB can act as a euphoriant and are believed to be aphrodisiac. Slang terms for GHB include liquid ecstasy, lollipops, liquid X or liquid E due to its tendency to produce euphoria and sociability and its use in the dance party scene.

Sports and athletics

Some athletes have used GHB or its analogs because of being marketed as anabolic agents, although there is no evidence that it builds muscle or improves performance.

Usage as a date-rape drug

GHB became known to the general public as a date-rape drug by the late 1990s. GHB is colourless and odorless and has been described as "very easy to add to drinks". When consumed, the victim will quickly feel groggy and sleepy and may become unconscious. Upon recovery they may have an impaired ability to recall events that have occurred during the period of intoxication. In these situations evidence and the identification of the perpetrator of the rape is often difficult.

It is also difficult to establish how often GHB is used to facilitate rape as it is difficult to detect in a urine sample after a day, and many victims may only recall the rape some time after its occurrence; however, a 2006 study suggested that there was "no evidence to suggest widespread date rape drug use" in the UK, and that less than 2% of cases involved GHB, while 17% involved cocaine, and a survey in the Netherlands published in 2010 found that the proportion of drug-related rapes where GHB was used appeared to be greatly overestimated by the media. More recently, a study in Western Australia reviewed the pre-hospital context given in medical records around emergency department presentations with analytical confirmation of GHB exposure. This study found that most cases reported daily dosing and subsequent accidental overdose rather than their presentation being associated with date-rape.

There have been several high-profile cases of GHB as a date-rape drug that received national attention in the United States. In early 1999, a 15-year-old girl, Samantha Reid of Rockwood, Michigan, died from GHB poisoning. Reid's death inspired the legislation titled the "Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act of 2000". This is the law that made GHB a Schedule 1 controlled substance. In the United Kingdom, British serial killer Stephen Port administered GHB to his victims by adding it to drinks given to them, raping them, and murdering four of them in his flat in Barking, East London.

GHB can be detected in hair. Hair testing can be a useful tool in court cases or for the victim's own information. Most over-the-counter urine test kits test only for date-rape drugs that are benzodiazepines, which GHB is not. To detect GHB in urine, the sample must be taken within four hours of GHB ingestion, and cannot be tested at home.

Adverse effects

Combination with alcohol

In humans, GHB has been shown to reduce the elimination rate (thus increasing the elimination time) of alcohol. This may explain the respiratory arrest that has been reported after ingestion of both drugs. A review of the details of 194 deaths attributed to or related to GHB over a ten-year period found that most were from respiratory depression caused by interaction with alcohol or other drugs.

Deaths

One publication has investigated 226 deaths attributed to GHB. Of the 226 deaths included, 213 had a cardiorespiratory arrest and 13 had fatal accidents. Seventy-one of these deaths (34%) had no co-intoxicants. Postmortem blood GHB was 18–4400 mg/L (median=347) in deaths negative for co-intoxicants.

One report has suggested that sodium oxybate overdose might be fatal, based on deaths of three patients who had been prescribed the drug. However, for two of the three cases, post-mortem GHB concentrations were 141 and 110 mg/L, which is within the expected range of concentrations for GHB after death, and the third case was a patient with a history of intentional drug overdose. The toxicity of GHB has been an issue in criminal trials, as in the death of Felicia Tang, where the defense argued that death was due to GHB, not murder.

GHB is produced in the body in very small amounts, and blood levels may climb after death to levels in the range of 30–50 mg/L. Levels higher than this are found in GHB deaths. Levels lower than this may be due to GHB or to postmortem endogenous elevations.

Neurotoxicity

In multiple studies, GHB has been found to impair spatial memory, working memory, learning and memory in rats with chronic administration. These effects are associated with decreased NMDA receptor expression in the cerebral cortex and possibly other areas as well. In addition, the neurotoxicity appears to be caused by oxidative stress.

Addiction

Addiction occurs when repeated drug use disrupts the normal balance of brain circuits that control rewards, memory and cognition, ultimately leading to compulsive drug taking.

Rats forced to consume massive doses of GHB will intermittently prefer GHB solution to water.

Withdrawal

GHB has also been associated with a withdrawal syndrome of insomnia, anxiety, and tremor that usually resolves within three to twenty-one days. The withdrawal syndrome can be severe producing acute delirium and may require hospitalization in an intensive care unit for management. Management of GHB dependence involves considering the person's age, comorbidity and the pharmacological pathways of GHB. The mainstay of treatment for severe withdrawal is supportive care and benzodiazepines for control of acute delirium, but larger doses are often required compared to acute delirium of other causes (e.g. > 100 mg/d of diazepam). Baclofen has been suggested as an alternative or adjunct to benzodiazepines based on anecdotal evidence and some animal data. However, there is less experience with the use of baclofen for GHB withdrawal, and additional research in humans is needed. Baclofen was first suggested as an adjunct because benzodiazepines do not affect GABAB receptors and therefore have no cross-tolerance with GHB while baclofen, which works via GABAB receptors, is cross-tolerant with GHB and may be more effective in alleviating withdrawal effects of GHB.

GHB withdrawal is not widely discussed in textbooks and some psychiatrists, general practitioners, and even hospital emergency physicians may not be familiar with this withdrawal syndrome.

Overdose

Overdose of GHB can sometimes be difficult to treat because of its multiple effects on the body. GHB tends to cause rapid unconsciousness at doses above 3500 mg, with single doses over 7000 mg often causing life-threatening respiratory depression, and higher doses still inducing bradycardia and cardiac arrest. Other side-effects include convulsions (especially when combined with stimulants), and nausea/vomiting (especially when combined with alcohol).

The greatest life threat due to GHB overdose (with or without other substances) is respiratory arrest. Other relatively common causes of death due to GHB ingestion include aspiration of vomitus, positional asphyxia, and trauma sustained while intoxicated (e.g., motor vehicle accidents while driving under the influence of GHB). The risk of aspiration pneumonia and positional asphyxia risk can be reduced by laying the patient down in the recovery position. People are most likely to vomit as they become unconscious, and as they wake up. It is important to keep the victim awake and moving; the victim must not be left alone due to the risk of death through vomiting. Frequently the victim will be in a good mood but this does not mean the victim is not in danger. GHB overdose is a medical emergency and immediate assessment in an emergency department is needed.

Convulsions from GHB can be treated with the benzodiazepines diazepam or lorazepam. Even though these benzodiazepines are also CNS depressants, they primarily modulate GABAA receptors whereas GHB is primarily a GABAB receptor agonist, and so do not worsen CNS depression as much as might be expected.

Because of the faster and more complete absorption of GBL relative to GHB, its dose-response curve is steeper, and overdoses of GBL tend to be more dangerous and problematic than overdoses involving only GHB or 1,4-B. Any GHB/GBL overdose is a medical emergency and should be cared for by appropriately trained personnel.

A newer synthetic drug, SCH-50911, which acts as a selective GABAB antagonist, quickly reverses GHB overdose in mice. However, this treatment has yet to be tried in humans, and it is unlikely that it will be researched for this purpose in humans due to the illegal nature of clinical trials of GHB and the lack of medical indemnity coverage inherent in using an untested treatment for a life-threatening overdose.

Detection of use

GHB may be quantitated in blood or plasma to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, to provide evidence in an impaired driving, or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma GHB concentrations are usually in a range of 50–250 mg/L in persons receiving the drug therapeutically (during general anesthesia), 30–100 mg/L in those arrested for impaired driving, 50–500 mg/L in acutely intoxicated patients and 100–1000 mg/L in victims of fatal overdosage. Urine is often the preferred specimen for routine drug abuse monitoring purposes. Both γ-butyrolactone (GBL) and 1,4-butanediol are converted to GHB in the body.

In January 2016, it was announced scientists had developed a way to detect GHB, among other things, in saliva.

Endogenous production

Cells produce GHB by reduction of succinic semialdehyde via succinic semialdehyde reductase (SSR). This enzyme appears to be induced by cAMP levels, meaning substances that elevate cAMP, such as forskolin and vinpocetine, may increase GHB synthesis and release. Conversely, endogeneous GHB production in those taking valproic acid will be inhibited via inhibition of the conversion from succinic acid semialdehyde to GHB. People with the disorder known as succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, also known as γ-hydroxybutyric aciduria, have elevated levels of GHB in their urine, blood plasma and cerebrospinal fluid.

The precise function of GHB in the body is not clear. It is known, however, that the brain expresses a large number of receptors that are activated by GHB. These receptors are excitatory, however, and therefore not responsible for the sedative effects of GHB; they have been shown to elevate the principal excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate. The benzamide antipsychotics—amisulpride, nemonapride, etc.—have been shown to bind to these GHB-activated receptors in vivo. Other antipsychotics were tested and were not found to have an affinity for this receptor.

GHB is a precursor to GABA, glutamate, and glycine in certain brain areas.

In spite of its demonstrated neurotoxicity, (see relevant section, above), GHB has neuroprotective properties, and has been found to protect cells from hypoxia.

Natural fermentation by-product

GHB is also produced as a result of fermentation and so is found in small quantities in some beers and wines, in particular fruit wines. The amount found in wine is pharmacologically insignificant and not sufficient to produce psychoactive effects.

Pharmacology

GHB has at least two distinct binding sites in the central nervous system. GHB acts as an agonist at the inhibitory GHB receptor and as a weak agonist at the inhibitory GABAB receptor. GHB is a naturally occurring substance that acts in a similar fashion to some neurotransmitters in the mammalian brain. GHB is probably synthesized from GABA in GABAergic neurons, and released when the neurons fire.

GHB has been found to activate oxytocinergic neurons in the supraoptic nucleus.

If taken orally, GABA itself does not effectively cross the blood–brain barrier.

GHB induces the accumulation of either a derivative of tryptophan or tryptophan itself in the extracellular space, possibly by increasing tryptophan transport across the blood–brain barrier. The blood content of certain neutral amino-acids, including tryptophan, is also increased by peripheral GHB administration. GHB-induced stimulation of tissue serotonin turnover may be due to an increase in tryptophan transport to the brain and in its uptake by serotonergic cells. As the serotonergic system may be involved in the regulation of sleep, mood, and anxiety, the stimulation of this system by high doses of GHB may be involved in certain neuropharmacological events induced by GHB administration.

However, at therapeutic doses, GHB reaches much higher concentrations in the brain and activates GABAB receptors, which are primarily responsible for its sedative effects. GHB's sedative effects are blocked by GABAB antagonists.

The role of the GHB receptor in the behavioural effects induced by GHB is more complex. GHB receptors are densely expressed in many areas of the brain, including the cortex and hippocampus, and these are the receptors that GHB displays the highest affinity for. There has been somewhat limited research into the GHB receptor; however, there is evidence that activation of the GHB receptor in some brain areas results in the release of glutamate, the principal excitatory neurotransmitter. Drugs that selectively activate the GHB receptor cause absence seizures in high doses, as do GHB and GABAB agonists.

Activation of both the GHB receptor and GABAB is responsible for the addictive profile of GHB. GHB's effect on dopamine release is biphasic. Low concentrations stimulate dopamine release via the GHB receptor. Higher concentrations inhibit dopamine release via GABAB receptors as do other GABAB agonists such as baclofen and phenibut. After an initial phase of inhibition, dopamine release is then increased via the GHB receptor. Both the inhibition and increase of dopamine release by GHB are inhibited by opioid antagonists such as naloxone and naltrexone. Dynorphin may play a role in the inhibition of dopamine release via kappa opioid receptors.

This explains the paradoxical mix of sedative and stimulatory properties of GHB, as well as the so-called "rebound" effect, experienced by individuals using GHB as a sleeping agent, wherein they awake suddenly after several hours of GHB-induced deep sleep. That is to say that, over time, the concentration of GHB in the system decreases below the threshold for significant GABAB receptor activation and activates predominantly the GHB receptor, leading to wakefulness.

Recently, analogs of GHB, such as 4-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoic acid (UMB68) have been synthesised and tested on animals, in order to gain a better understanding of GHB's mode of action. Analogues of GHB such as 3-methyl-GHB, 4-methyl-GHB, and 4-phenyl-GHB have been shown to produce similar effects to GHB in some animal studies, but these compounds are even less well researched than GHB itself. Of these analogues, only 4-methyl-GHB (γ-hydroxyvaleric acid, GHV) and a prodrug form γ-valerolactone (GVL) have been reported as drugs of abuse in humans, and on the available evidence seem to be less potent but more toxic than GHB, with a particular tendency to cause nausea and vomiting.

Other prodrug ester forms of GHB have also rarely been encountered by law enforcement, including 1,4-butanediol diacetate (BDDA/DABD), methyl-4-acetoxybutanoate (MAB), and ethyl-4-acetoxybutanoate (EAB), but these are, in general, covered by analogue laws in jurisdictions where GHB is illegal, and little is known about them beyond their delayed onset and longer duration of action. The intermediate compound γ-hydroxybutyraldehyde (GHBAL) is also a prodrug for GHB; however, as with all aliphatic aldehydes this compound is caustic and is strong-smelling and foul-tasting; actual use of this compound as an intoxicant is likely to be unpleasant and result in severe nausea and vomiting.

Only a minor portion (1–5%) of the administered GHB dose is excreted unchanged in the urine. Studies have shown that the maximum concentration of GHB in urine appears within 1 hour and rapidly declines thereafter. The vast majority (95–98%) undergoes extensive metabolism in the liver. GHB is broken down through a series of enzymatic pathways. The primary route involves conversion to succinic semialdehyde (SSA) by either GHB dehydrogenase (ADH) or GHB transhydrogenase. SSA is further oxidized by succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) to succinic acid, which enters the Krebs cycle and is ultimately converted into carbon dioxide and water.

Both of the metabolic breakdown pathways shown for GHB can run in either direction, depending on the concentrations of the substances involved, so the body can make its own GHB either from GABA or from succinic semialdehyde. Under normal physiological conditions, the concentration of GHB in the body is rather low, and the pathways would run in the reverse direction to what is shown here to produce endogenous GHB. However, when GHB is consumed for recreational or health promotion purposes, its concentration in the body is much higher than normal, which changes the enzyme kinetics so that these pathways operate to metabolise GHB rather than producing it.

History

Alexander Zaytsev worked on this chemical family and published work on it in 1874. The first extended research into GHB and its use in humans was conducted in the early 1960s by Henri Laborit to use in studying the neurotransmitter GABA. It was studied in a range of uses including obstetric surgery and during childbirth and as an anxiolytic; there were anecdotal reports of it having antidepressant and aphrodisiac effects as well. It was also studied as an intravenous anesthetic agent and was marketed for that purpose starting in 1964 in Europe but it was not widely adopted as it caused seizures; as of 2006 that use was still authorized in France and Italy but not widely used. It was also studied to treat alcohol addiction; while the evidence for this use is weak; however, sodium oxybate is marketed for this use in Italy.

GHB and sodium oxybate were also studied for use in narcolepsy from the 1960s onwards.

In May 1990 GHB was introduced as a dietary supplement and was marketed to body builders, for help with weight control and as a sleep aid, and as a "replacement" for l-tryptophan, which was removed from the market in November 1989 when batches contaminated with trace impurities were found to cause eosinophilia–myalgia syndrome, although eosinophilia–myalgia syndrome is also tied to tryptophan overload. In 2001 tryptophan supplement sales were allowed to resume, and in 2005 the FDA ban on tryptophan supplement importation was lifted. By November 1989 57 cases of illness caused by the GHB supplements had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with people having taken up to three teaspoons of GHB; there were no deaths but nine people needed care in an intensive care unit. The FDA issued a warning in November 1990 that sale of GHB was illegal. GHB continued to be manufactured and sold illegally and it and analogs were adopted as a club drug and came to be used as a date rape drug, and the DEA made seizures and the FDA reissued warnings several times throughout the 1990s.

At the same time, research on the use of GHB in the form of sodium oxybate had formalized, as a company called Orphan Medical had filed an investigational new drug application and was running clinical trials with the intention of gaining regulatory approval for use to treat narcolepsy.

A popular children's toy, Bindeez (also known as Aqua Dots, in the United States), produced by Melbourne company Moose, was banned in Australia in early November 2007 when it was discovered that 1,4-butanediol (1,4-B), which is metabolized into GHB, had been substituted for the non-toxic plasticiser 1,5-pentanediol in the bead manufacturing process. Three young children were hospitalized as a result of ingesting a large number of the beads, and the toy was recalled.

Legal status

In the United States, GHB was placed on Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act in March 2000. However, used in sodium oxybate under an IND or NDA from the US FDA, it is considered a Schedule III substance but with Schedule I trafficking penalties, one of several drugs that are listed in multiple schedules.

On 20 March 2001, the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs placed GHB in Schedule IV of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

In the UK GHB was made a class C drug in June 2003. In October 2013 the ACMD recommended upgrading it from schedule IV to schedule II in line with UN recommendations. Their report concluded that the minimal use of Xyrem in the UK meant that prescribers would be minimally inconvenienced by the rescheduling. This advice was followed and GHB was moved to schedule 2 on 7 January 2015. In April 2022 GHB was changed from class C to class B.

In Hong Kong, GHB is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purposes. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without prescription can be fined HK$10,000. The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing the substance is a HK$150,000 fine and life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a HK$100,000 fine or five years of jail time.

In Canada, GHB has been a Schedule I controlled substance since 6 November 2012 (the same schedule that contains heroin and cocaine). Prior to that date, it was a Schedule III controlled substance (the same schedule that contains amphetamines and LSD).

In New Zealand and Australia, GHB, 1,4-B, and GBL are all Class B illegal drugs, along with any possible esters, ethers, and aldehydes. GABA itself is also listed as an illegal drug in these jurisdictions, which seems unusual given its failure to cross the blood–brain barrier, but there was a perception among legislators that all known analogues should be covered as far as this was possible. Attempts to circumvent the illegal status of GHB have led to the sale of derivatives such as 4-methyl-GHB (γ-hydroxyvaleric acid, GHV) and its prodrug form γ-valerolactone (GVL), but these are also covered under the law by virtue of their being "substantially similar" to GHB or GBL, so importation, sale, possession and use of these compounds is also considered to be illegal.

In Chile, GHB is a controlled drug under the law Ley de substancias psicotrópicas y estupefacientes (psychotropic substances and narcotics).

In Norway and in Switzerland, GHB is considered a narcotic and is only available by prescription under the trade name Xyrem (Union Chimique Belge S.A.).

Sodium oxybate is also used therapeutically in Italy under the brand name Alcover for treatment of alcohol withdrawal and dependence.

See also

- Beta-Hydroxybutyric acid

- γ-Hydroxyvaleric acid (GHV)

- γ-Valerolactone (GVL)

- β-Hydroxy β-methylbutyric acid (HMB)

References

- "Pingers, pingas, pingaz: how drug slang affects the way we use and understand drugs". The Conversation. 8 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- "GHB/GBL "G"". Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- Tay, E., Lo, W. K. W., & Murnion, B. (2022). Current Insights on the Impact of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) Abuse. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 13, 13–23. doi:10.2147/SAR.S315720

- "Therapeutic Goods (Poisons Standard—June 2024) Instrument 2024". 30 May 2024.

- Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "What is GHB?" (PDF). Dea.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "2000 – Addition of Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid to Schedule I". US Department of Justice via the Federal Register. 13 March 2000. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Riviello RJ (2010). Manual of forensic emergency medicine : a guide for clinicians. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 42. ISBN 978-0763744625.

- ^ Busardò FP, Jones AW (January 2015). "GHB pharmacology and toxicology: acute intoxication, concentrations in blood and urine in forensic cases and treatment of the withdrawal syndrome". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 47–70. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210215423. PMC 4462042. PMID 26074743.

- "Sodium Oxybate: MedlinePlus Drug Information". Nlm.nih.gov. 28 July 2010. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ Benzer TI, Cameron S (8 January 2007). VanDeVoort JT, Benitez JG (eds.). "Toxicity, Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ US Drug Enforcement Administration. "GHB, GBL and 1,4BD as Date Rape Drugs". Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Weil A, Winifred R (1993). "Depressants". From Chocolate to Morphine (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-395-66079-9.

- Mayer G (May 2012). "The use of sodium oxybate to treat narcolepsy". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 12 (5): 519–29. doi:10.1586/ern.12.42. PMID 22550980. S2CID 43706704.

- Caputo F, Mirijello A, Cibin M, Mosti A, Ceccanti M, Domenicali M, et al. (April 2015). "Novel strategies to treat alcohol dependence with sodium oxybate according to clinical practice". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 19 (7): 1315–20. PMID 25912595.

- Keating GM (January 2014). "Sodium oxybate: a review of its use in alcohol withdrawal syndrome and in the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol dependence". Clinical Drug Investigation. 34 (1): 63–80. doi:10.1007/s40261-013-0158-x. PMID 24307430. S2CID 2056246.

- Leone MA, Vigna-Taglianti F, Avanzi G, Brambilla R, Faggiano F, et al. (Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group) (February 2010). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) for treatment of alcohol withdrawal and prevention of relapses". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006266. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006266.pub2. PMID 20166080.

There is insufficient randomised evidence to be confident of a difference between GHB and placebo, or to determine reliably if GHB is more or less effective than other drugs for the treatment of alcohol withdrawl [sic?] or the prevention of relapses.

- Leone MA, Vigna-Taglianti F, Avanzi G, Brambilla R, Faggiano F (2010). "cochranelibrary.com". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006266. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006266.pub2. PMID 20166080. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (June 2015). "An update on pharmacotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 16 (9): 1347–68. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1047343. PMID 26001183. S2CID 24246355.

- Staud R (August 2011). "Sodium oxybate for the treatment of fibromyalgia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 12 (11): 1789–98. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.589836. PMID 21679091. S2CID 33026097.

- "FDA Approval Letter for Xyrem; Indication: Cataplexy associated with narcolepsy; 17 July 2002" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- "FDA Approval Letter for Xyrem; Indication: EDS (Excessive Daytime Sleepiness) associated with narcolepsy; 18 November 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Scrima L, Hartman PG, Johnson FH, Thomas EE, Hiller FC (December 1990). "The effects of gamma-hydroxybutyrate on the sleep of narcolepsy patients: a double-blind study". Sleep. 13 (6): 479–90. doi:10.1093/sleep/13.6.479. PMID 2281247.

- Scrima L, Johnson FH, Hiller FC (1991). "Long-Term Effect of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate on Sleep in Narcolepsy Patients". Sleep Research. 20: 330.

- Van Cauter E, Plat L, Scharf MB, Leproult R, Cespedes S, L'Hermite-Balériaux M, et al. (August 1997). "Simultaneous stimulation of slow-wave sleep and growth hormone secretion by gamma-hydroxybutyrate in normal young Men". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 100 (3): 745–53. doi:10.1172/JCI119587. PMC 508244. PMID 9239423.

- Scrima L, Shander D (January 1991). "Letter to Editor on article: Re: Narcolepsy Review (Aldrich MS: 8-9-91)". The New England Journal of Medicine. 324 (4): 270–72. doi:10.1056/nejm199101243240416. PMID 1985252.

- "FDA Approved Labeling Text: Xyrem® (sodium oxybate) oral solution" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 18 November 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Guiraud J, Addolorato G, Aubin HJ, Batel P, de Bejczy A, Caputo F, et al. (July 2021). "Treating alcohol dependence with an abuse and misuse deterrent formulation of sodium oxybate: Results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 52: 18–30. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.06.003. hdl:11392/2483205. PMID 34237655.

- ^ Schep LJ, Knudsen K, Slaughter RJ, Vale JA, Mégarbane B (July 2012). "The clinical toxicology of γ-hydroxybutyrate, γ-butyrolactone and 1,4-butanediol". Clinical Toxicology. 50 (6): 458–70. doi:10.3109/15563650.2012.702218. PMID 22746383. S2CID 19697449.

- Sellman JD, Robinson GM, Beasley R (January 2009). "Should ethanol be scheduled as a drug of high risk to public health?". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (1): 94–100. doi:10.1177/0269881108091596. PMID 18583435.

- ^ Galloway GP, Frederick-Osborne SL, Seymour R, Contini SE, Smith DE (April 2000). "Abuse and therapeutic potential of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid". Alcohol. 20 (3): 263–69. doi:10.1016/S0741-8329(99)00090-7. PMID 10869868.

- Thai D, Dyer JE, Benowitz NL, Haller CA (October 2006). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate and ethanol effects and interactions in humans". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 26 (5): 524–29. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000237944.57893.28. PMC 2766839. PMID 16974199.

- "The Vaults Of Erowid" Archived 22 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Erowid.org (18 March 2009). Retrieved on 27 September 2012.

- US 4393236, Klosa, Joseph, "Production of nonhygroscopic salts of 4-hydroxybutyric acid", issued 12 July 1983

- "1,4-Butanediol". PubChem. U.S National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Kapoor P, Deshmukh R, Kukreja I (October 2013). "GHB acid: A rage or reprive". Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research. 4 (4): 173–178. doi:10.4103/2231-4040.121410. PMC 3853692. PMID 24350046.

- ^ Jones C (June 2001). "Suspicious death related to gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) toxicity". Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine. 8 (2): 74–76. doi:10.1054/jcfm.2001.0473. PMID 15274975.

- Kam PC, Yoong FF (December 1998). "Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid: an emerging recreational drug". Anaesthesia. 53 (12): 1195–98. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00603.x. PMID 10193223.

In the UK, GHB has been available in the night clubs around London since 1994...

- Carter LP, Pardi D, Gorsline J, Griffiths RR (September 2009). "Illicit gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and pharmaceutical sodium oxybate (Xyrem): differences in characteristics and misuse". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 104 (1–2): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.012. PMC 2713368. PMID 19493637.

- Klein M, Kramer F (February 2004). "Rave drugs: pharmacological considerations". AANA Journal. 72 (1): 61–67. PMID 15098519.

- "Warning on Risk of 'Party Drug' Chemicals". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 12 May 1999. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Németh Z, Kun B, Demetrovics Z (September 2010). "The involvement of gamma-hydroxybutyrate in reported sexual assaults: a systematic review". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (9): 1281–7. doi:10.1177/0269881110363315. PMID 20488831. S2CID 25496192.

- ElSohly MA, Salamone SJ (1999). "Prevalence of drugs used in cases of alleged sexual assault". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 23 (3): 141–6. doi:10.1093/jat/23.3.141. PMID 10369321.

- "No evidence to suggest widespread date rape drug use'". 16 November 2006. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- "Date-rape drugs 'not widespread'". BBC News. 16 November 2006. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Alcohol and other popular Date Rape Drugs. udel.edu

- "Labs making date-rape drug raided". The Independent. 10 July 2008. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- Smith JL, Greene S, McCutcheon D, Weber C, Kotkis E, Soderstrom J, et al. (March 2024). "A multicentre case series of analytically confirmed gamma-hydroxybutyrate intoxications in Western Australian emergency departments: Pre-hospital circumstances, co-detections and clinical outcomes". Drug and Alcohol Review. 43 (4): 984–996. doi:10.1111/dar.13830. PMID 38426636.

- Martin JH (16 January 2009). "Remembering Samantha Reid: 10th anniversary of teen's GHB death". thenewsherald.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- "Stephen Port: Serial killer guilty of murdering four men". BBC News. 23 November 2016.

- Kintz P, Cirimele V, Jamey C, Ludes B (January 2003). "Testing for GHB in hair by GC/MS/MS after a single exposure. Application to document sexual assault" (PDF). Journal of Forensic Sciences. 48 (1): 195–200. doi:10.1520/JFS2002209. PMID 12570228. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2012.

- "Drink Speaks the Truth: Forensic Investigation of Drug Facilitated Sexual Assaults". 20 June 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Lott S, Piper T, Mehling LM, Spottke A, Maas A, Thevis M, et al. (2015). "Measurement of exogenous gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) in urine using isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS)" (PDF). Toxichem Krimtech. 82: 264. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

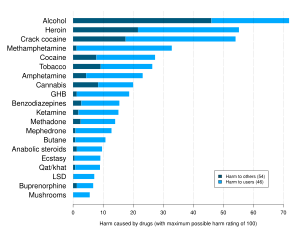

- Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- Poldrugo F, Addolorato G (1999). "The role of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid in the treatment of alcoholism: from animal to clinical studies". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 34 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1093/alcalc/34.1.15. PMID 10075397.

- Zvosec et al. Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Science in Seattle, 2006. Web.archive.org (3 December 2007). Retrieved on 24 December 2011.

- Zvosec DL, Smith SW, Porrata T, Strobl AQ, Dyer JE (March 2011). "Case series of 226 γ-hydroxybutyrate-associated deaths: lethal toxicity and trauma". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 29 (3): 319–32. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.11.008. PMID 20825811.

- Zvosec DL, Smith SW, Hall BJ (April 2009). "Three deaths associated with use of Xyrem". Sleep Medicine. 10 (4): 490–93. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.01.005. PMID 19269893.

- Feldman NT (April 2009). "Xyrem safety: the debate continues". Sleep Medicine. 10 (4): 405–06. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.02.002. PMID 19332385.

- Zvosec DL, Smith SW (January 2010). "Response to Editorial: "Xyrem safety: The debate continues"". Sleep Medicine. 11 (1): 108, author reply 108–09. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.08.004. PMID 19959395.

- ^ Sircar R, Basak A (December 2004). "Adolescent gamma-hydroxybutyric acid exposure decreases cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor and impairs spatial learning". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 79 (4): 701–08. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.022. PMID 15582677. S2CID 31736568.

- García FB, Pedraza C, Arias JL, Navarro JF (August 2006). "". Psicothema (in Spanish). 18 (3): 519–24. PMID 17296081.

- Sircar R, Basak A, Sircar D (October 2008). "Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid-induced cognitive deficits in the female adolescent rat". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1139 (1): 386–89. Bibcode:2008NYASA1139..386S. doi:10.1196/annals.1432.044. PMID 18991885. S2CID 1823886.

- Sgaravatti AM, Sgarbi MB, Testa CG, Durigon K, Pederzolli CD, Prestes CC, et al. (February 2007). "Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid induces oxidative stress in cerebral cortex of young rats". Neurochemistry International. 50 (3): 564–70. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2006.11.007. PMID 17197055. S2CID 43049617.

- Sgaravatti AM, Magnusson AS, Oliveira AS, Mescka CP, Zanin F, Sgarbi MB, et al. (June 2009). "Effects of 1,4-butanediol administration on oxidative stress in rat brain: study of the neurotoxicity of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid in vivo". Metabolic Brain Disease. 24 (2): 271–82. doi:10.1007/s11011-009-9136-7. PMID 19296210. S2CID 13460935.

- Department of Health and Human Services, SAMHSA Office of Applied Studies 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (ages 12 years and up); American Heart Association; Johns Hopkins University study, Principles of Addiction Medicine; Psychology Today; National Gambling Impact Commission Study; National Council on Problem Gambling; Illinois Institute for Addiction Recovery; Society for Advancement of Sexual Health; All Psych Journal

- Addiction and the Brain. Time

- Colombo G, Agabio R, Balaklievskaia N, Diaz G, Lobina C, Reali R, et al. (October 1995). "Oral self-administration of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid in the rat". European Journal of Pharmacology. 285 (1): 103–07. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(95)00493-5. PMID 8846805.

- "Is GHB toxic? Addictive? Dangerous?". lycaeum.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011.

- Galloway GP, Frederick SL, Staggers FE, Gonzales M, Stalcup SA, Smith DE (January 1997). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate: an emerging drug of abuse that causes physical dependence". Addiction. 92 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb03640.x. PMID 9060200.

- "GHB: An Important Pharmacologic and Clinical Update". Ualberta.ca. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- Santos C, Olmedo RE (March 2017). "Sedative-Hypnotic Drug Withdrawal Syndrome: Recognition And Treatment". Emergency Medicine Practice. 19 (3): 1–20. PMID 28186869.

- LeTourneau JL, Hagg DS, Smith SM (2008). "Baclofen and gamma-hydroxybutyrate withdrawal". Neurocritical Care. 8 (3): 430–33. doi:10.1007/s12028-008-9062-2. PMC 2630388. PMID 18266111.

- Carter LP, Koek W, France CP (January 2009). "Behavioral analyses of GHB: receptor mechanisms". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 121 (1): 100–14. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.003. PMC 2631377. PMID 19010351.

- van Noorden MS, van Dongen LC, Zitman FG, Vergouwen TA (2009). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate withdrawal syndrome: dangerous but not well-known". General Hospital Psychiatry. 31 (4): 394–96. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.11.001. PMID 19555805.

- Allen L, Alsalim W (April 2006). "Best evidence topic report. Gammahydroxybutyrate overdose and physostigmine". Emergency Medicine Journal. 23 (4): 300–01. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.035139. PMC 2579509. PMID 16549578.

- Michael H, Harrison M (January 2005). "Best evidence topic report: endotracheal intubation in gamma-hydroxybutyric acid intoxication and overdose". Emergency Medicine Journal. 22 (1): 43. doi:10.1136/emj.2004.021154. PMC 1726538. PMID 15611542.

- Morse BL, Vijay N, Morris ME (August 2012). "γ-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB)-induced respiratory depression: combined receptor-transporter inhibition therapy for treatment in GHB overdose". Molecular Pharmacology. 82 (2): 226–235. doi:10.1124/mol.112.078154. PMC 3400846. PMID 22561075.

- Zvosec DL, Smith SW, Porrata T, Strobl AQ, Dyer JE (March 2011). "Case series of 226 γ-hydroxybutyrate-associated deaths: lethal toxicity and trauma". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 29 (3): 319–332. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.11.008. PMID 20825811.

- Allen MJ, Sabir S, Sharma S (2022). "GABA Receptor". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30252380. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- Carai MA, Colombo G, Gessa GL (June 2005). "Resuscitative effect of a gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptor antagonist on gamma-hydroxybutyric acid mortality in mice". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 45 (6): 614–19. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.013. PMID 15940094.

- Couper FJ, Thatcher JE, Logan BK (September 2004). "Suspected GHB overdoses in the emergency department". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 28 (6): 481–84. doi:10.1093/jat/28.6.481. PMID 15516299.

- Marinetti LJ, Isenschmid DS, Hepler BR, Kanluen S (2005). "Analysis of GHB and 4-methyl-GHB in postmortem matrices after long-term storage". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 29 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1093/jat/29.1.41. PMID 15808012.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 680–84.

- "New spit test for 'date rape' drug developed in the UK". BBC News. August 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Kemmel V, Taleb O, Perard A, Andriamampandry C, Siffert JC, Mark J, et al. (October 1998). "Neurochemical and electrophysiological evidence for the existence of a functional gamma-hydroxybutyrate system in NCB-20 neurons". Neuroscience. 86 (3): 989–1000. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00085-2. PMID 9692734. S2CID 21001043.

- Löscher W (2002). "Valproic Acid: Mechanism of Action". In Levy RH, Mattson RH, Meldrum BS, Perucca E (eds.). Antiepileptic drugs (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 774. ISBN 978-0-7817-2321-3. Archived from the original on 18 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Succinic Semialdehyde Dehydrogenase Deficiency Archived 6 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Andriamampandry C, Taleb O, Viry S, Muller C, Humbert JP, Gobaille S, et al. (September 2003). "Cloning and characterization of a rat brain receptor that binds the endogenous neuromodulator gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB)". FASEB Journal. 17 (12): 1691–93. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0846fje. PMID 12958178. S2CID 489179.

- ^ Castelli MP, Ferraro L, Mocci I, Carta F, Carai MA, Antonelli T, et al. (November 2003). "Selective gamma-hydroxybutyric acid receptor ligands increase extracellular glutamate in the hippocampus, but fail to activate G protein and to produce the sedative/hypnotic effect of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid". Journal of Neurochemistry. 87 (3): 722–732. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02037.x. PMID 14535954. S2CID 82175813.

- Maitre M, Ratomponirina C, Gobaille S, Hodé Y, Hechler V (April 1994). "Displacement of gamma-hydroxybutyrate binding by benzamide neuroleptics and prochlorperazine but not by other antipsychotics". European Journal of Pharmacology. 256 (2): 211–14. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(94)90248-8. PMID 7914168.

- Gobaille S, Hechler V, Andriamampandry C, Kemmel V, Maitre M (July 1999). "gamma-Hydroxybutyrate modulates synthesis and extracellular concentration of gamma-aminobutyric acid in discrete rat brain regions in vivo". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 290 (1): 303–09. PMID 10381791.

- Ottani A, Saltini S, Bartiromo M, Zaffe D, Renzo Botticelli A, Ferrari A, et al. (October 2003). "Effect of gamma-hydroxybutyrate in two rat models of focal cerebral damage". Brain Research. 986 (1–2): 181–90. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(03)03252-9. PMID 12965243. S2CID 54374774.

- Elliott S, Burgess V (July 2005). "The presence of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) in alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages". Forensic Science International. 151 (2–3): 289–92. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.02.014. PMID 15939164.

- Wu Y, Ali S, Ahmadian G, Liu CC, Wang YT, Gibson KM, et al. (December 2004). "Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and gamma-aminobutyric acidB receptor (GABABR) binding sites are distinctive from one another: molecular evidence". Neuropharmacology. 47 (8): 1146–56. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.08.019. PMID 15567424. S2CID 54233206.

- Cash CD, Gobaille S, Kemmel V, Andriamampandry C, Maitre M (December 1999). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate receptor function studied by the modulation of nitric oxide synthase activity in rat frontal cortex punches". Biochemical Pharmacology. 58 (11): 1815–19. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00265-8. PMID 10571257.

- ^ Maitre M, Humbert JP, Kemmel V, Aunis D, Andriamampandry C (March 2005). "[A mechanism for gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) as a drug and a substance of abuse]". Médecine/Sciences (in French). 21 (3): 284–89. doi:10.1051/medsci/2005213284. PMID 15745703.

- Waszkielewicz A, Bojarski J (2004). "Gamma-hydrobutyric acid (GHB) and its chemical modifications: a review of the GHBergic system" (PDF). Polish Journal of Pharmacology. 56 (1): 43–49. PMID 15047976. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- McGregor IS, Callaghan PD, Hunt GE (May 2008). "From ultrasocial to antisocial: a role for oxytocin in the acute reinforcing effects and long-term adverse consequences of drug use?". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (2): 358–68. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.132. PMC 2442436. PMID 18475254.

- Kuriyama K, Sze PY (January 1971). "Blood-brain barrier to H3-gamma-aminobutyric acid in normal and amino oxyacetic acid-treated animals". Neuropharmacology. 10 (1): 103–08. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(71)90013-X. PMID 5569303.

- ^ Gobaille S, Schleef C, Hechler V, Viry S, Aunis D, Maitre M (March 2002). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate increases tryptophan availability and potentiates serotonin turnover in rat brain". Life Sciences. 70 (18): 2101–2112. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01526-0. PMID 12002803.

- Hedner T, Lundborg P (1983). "Effect of gammahydroxybutyric acid on serotonin synthesis, concentration and metabolism in the developing rat brain". Journal of Neural Transmission. 57 (1–2): 39–48. doi:10.1007/BF01250046. PMID 6194255. S2CID 9471705.

- Pardi D, Black J (2006). "gamma-Hydroxybutyrate/sodium oxybate: neurobiology, and impact on sleep and wakefulness". CNS Drugs. 20 (12): 993–1018. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620120-00004. PMID 17140279. S2CID 72211254.

- Dimitrijevic N, Dzitoyeva S, Satta R, Imbesi M, Yildiz S, Manev H (September 2005). "Drosophila GABA(B) receptors are involved in behavioral effects of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB)". European Journal of Pharmacology. 519 (3): 246–252. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.07.016. PMID 16129424.

- Pistis M, Muntoni AL, Pillolla G, Perra S, Cignarella G, Melis M, et al. (2005). "Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and the mesoaccumbens reward circuit: evidence for GABA(B) receptor-mediated effects". Neuroscience. 131 (2): 465–474. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.021. PMID 15708487. S2CID 54342374.

- ^ Kamal RM, van Noorden MS, Franzek E, Dijkstra BA, Loonen AJ, De Jong CA (2016). "The Neurobiological Mechanisms of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate Dependence and Withdrawal and Their Clinical Relevance: A Review". Neuropsychobiology. 73 (2): 65–80. doi:10.1159/000443173. hdl:2066/158441. PMID 27003176. S2CID 33389634.

- Banerjee PK, Snead OC (June 1995). "Presynaptic gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and gamma-aminobutyric acidB (GABAB) receptor-mediated release of GABA and glutamate (GLU) in rat thalamic ventrobasal nucleus (VB): a possible mechanism for the generation of absence-like seizures induced by GHB". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 273 (3): 1534–1543. PMID 7791129.

- Hechler V, Gobaille S, Bourguignon JJ, Maitre M (March 1991). "Extracellular events induced by gamma-hydroxybutyrate in striatum: a microdialysis study". Journal of Neurochemistry. 56 (3): 938–944. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02012.x. PMID 1847191. S2CID 86392963.

- Maitre M, Hechler V, Vayer P, Gobaille S, Cash CD, Schmitt M, et al. (November 1990). "A specific gamma-hydroxybutyrate receptor ligand possesses both antagonistic and anticonvulsant properties". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 255 (2): 657–663. PMID 2173754.

- Míguez I, Aldegunde M, Duran R, Veira JA (June 1988). "Effect of low doses of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid on serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine concentrations in rat brain areas". Neurochemical Research. 13 (6): 531–533. doi:10.1007/BF00973292. PMID 2457177. S2CID 27073926.

- Smolders I, De Klippel N, Sarre S, Ebinger G, Michotte Y (September 1995). "Tonic GABA-ergic modulation of striatal dopamine release studied by in vivo microdialysis in the freely moving rat". European Journal of Pharmacology. 284 (1–2): 83–91. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(95)00369-V. PMID 8549640.

- Mamelak M (1989). "Gammahydroxybutyrate: an endogenous regulator of energy metabolism". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 13 (4): 187–198. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(89)80053-3. PMID 2691926. S2CID 20217078.

- Oliveto A, Gentry WB, Pruzinsky R, Gonsai K, Kosten TR, Martell B, et al. (July 2010). "Behavioral effects of gamma-hydroxybutyrate in humans". Behavioural Pharmacology. 21 (4): 332–342. doi:10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833b3397. PMC 2911496. PMID 20526195.

- Wu H, Zink N, Carter LP, Mehta AK, Hernandez RJ, Ticku MK, et al. (May 2003). "A tertiary alcohol analog of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid as a specific gamma-hydroxybutyric acid receptor ligand". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 305 (2): 675–79. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.046797. PMID 12606613. S2CID 86191608.

- Felmlee MA, Morse BL, Morris ME (January 2021). "γ-Hydroxybutyric Acid: Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Toxicology". The AAPS Journal. 23 (1): 22. doi:10.1208/s12248-020-00543-z. PMC 8098080. PMID 33417072.

- Taxon ES, Halbers LP, Parsons SM (May 2020). "Kinetics aspects of Gamma-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1868 (5): 140376. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140376. PMID 31981617.

- Kamal RM, van Noorden MS, Franzek E, Dijkstra BA, Loonen AJ, De Jong CA (March 2016). "The Neurobiological Mechanisms of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate Dependence and Withdrawal and Their Clinical Relevance: A Review". Neuropsychobiology. 73 (2): 65–80. doi:10.1159/000443173. hdl:2066/158441. PMID 27003176.

- Lewis DE (2012). "Section 4.4.3 Aleksandr Mikhailovich Zaitsev". Early Russian organic chemists and their legacy. Springer. p. 79. ISBN 978-3642282195.

- Saytzeff A (1874). "Über die Reduction des Succinylchlorids". Liebigs Annalen der Chemie (in German). 171 (2): 258–90. doi:10.1002/jlac.18741710216. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Critical review of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB)" (PDF). 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2014.

- Laborit H, Jouany JM, Gerard J, Fabiani F (October 1960). "". Agressologie (in French). 1: 397–406. PMID 13758011.

- "Alcover: Riassunto delle Caratteristiche del Prodotto". Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. 31 March 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2018. Index page Archived 4 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Ito J, Hosaki Y, Torigoe Y, Sakimoto K (January 1992). "Identification of substances formed by decomposition of peak E substance in tryptophan". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 30 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(92)90139-C. PMID 1544609.

- Smith MJ, Garrett RH (November 2005). "A heretofore undisclosed crux of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome: compromised histamine degradation". Inflammation Research. 54 (11): 435–50. doi:10.1007/s00011-005-1380-7. PMID 16307217. S2CID 7785345.

- Kapalka GM (2010). Nutritional and herbal therapies for children and adolescents : a handbook for mental health clinicians. Elsevier/AP. ISBN 978-0-12-374927-7.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (November 1990). "Multistate outbreak of poisonings associated with illicit use of gamma hydroxy butyrate". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 39 (47): 861–63. PMID 2122223. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Dyer JE (July 1991). "gamma-Hydroxybutyrate: a health-food product producing coma and seizurelike activity". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (4): 321–24. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(91)90050-t. PMID 2054002.

- Institute of Medicine, National Research Council (US) Committee on the Framework for Evaluating the Safety of Dietary Supplements (2002). "Appendix D: Table of Food and Drug Administration Actions on Dietary Supplements". Proposed Framework for Evaluating the Safety of Dietary Supplements: For Comment. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "GHB: A Club Drug To Watch" (PDF). Substance Abuse Treatment Advisory. 2 (1). November 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Mason PE, Kerns WP (July 2002). "Gamma hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) intoxication". Academic Emergency Medicine. 9 (7): 730–79. doi:10.1197/aemj.9.7.730. PMID 12093716. S2CID 13325306.

- "Transcript: FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting". FDA. 6 June 2001. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Perry M, Pomfret J, Crabb RP (7 November 2007). "Australia bans China-made toy on toxic drug risk". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- "William J. Clinton: Statement on Signing the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act of 2000". 18 February 2000. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Gamma Hydroxybutyrate (GHB)". 2002. Archived from the original on 31 December 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Iversen L (3 October 2013). "ACMD advice on the scheduling of GHB" (PDF). UK Home Office. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "Circular 001/2015: A Change to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971: control of AH-7921, LSD–related compounds, tryptamines, and rescheduling of GHB". UK Home Office. 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "The Misuse of Drugs (Amendment No. 3) (England, Wales and Scotland) Regulations 2014". UK Home Office. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2022". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, SC 1996, c 19". Canadian Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- "FOR 30 June 1978 nr 08: Forskrift om narkotika m.v. (Narkotikalisten)" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Haller C, Thai D, Jacob P, Dyer JE (2006). "GHB urine concentrations after single-dose administration in humans". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 30 (6): 360–64. doi:10.1093/jat/30.6.360. PMC 2257868. PMID 16872565.

External links

- Gamma-hydroxybutyrate MS Spectrum

- EMCDDA Report on the risk assessment of GHB in the framework of the joint action on new synthetic drugs

- Erowid GHB Vault (also contains information about addiction and dangers)

- InfoFacts – Rohypnol and GHB (National Institute on Drug Abuse)

| Neurotransmitters | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid-derived |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lipid-derived |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nucleobase-derived |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin-derived | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hypnotics/sedatives (N05C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABAA |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GABAB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2-Adrenergic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HT2A |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orexin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2δ VDCC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Drugs which induce euphoria | |

|---|---|

| |

| See also: Recreational drug use |

| GHB receptor modulators | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor (ligands) |

| ||||||||||

| Transporter (blockers) |

| ||||||||||

| Enzyme (inhibitors) |

| ||||||||||

| GABA receptor modulators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionotropic |

| ||||

| Metabotropic |

| ||||