In cellular biology, the Wnt signaling pathways are a group of signal transduction pathways which begin with proteins that pass signals into a cell through cell surface receptors. The name Wnt, pronounced "wint", is a portmanteau created from the names Wingless and Int-1. Wnt signaling pathways use either nearby cell-cell communication (paracrine) or same-cell communication (autocrine). They are highly evolutionarily conserved in animals, which means they are similar across animal species from fruit flies to humans.

Three Wnt signaling pathways have been characterized: the canonical Wnt pathway, the noncanonical planar cell polarity pathway, and the noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway. All three pathways are activated by the binding of a Wnt-protein ligand to a Frizzled family receptor, which passes the biological signal to the Dishevelled protein inside the cell. The canonical Wnt pathway leads to regulation of gene transcription, and is thought to be negatively regulated in part by the SPATS1 gene. The noncanonical planar cell polarity pathway regulates the cytoskeleton that is responsible for the shape of the cell. The noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway regulates calcium inside the cell.

Wnt signaling was first identified for its role in carcinogenesis, then for its function in embryonic development. The embryonic processes it controls include body axis patterning, cell fate specification, cell proliferation and cell migration. These processes are necessary for proper formation of important tissues including bone, heart and muscle. Its role in embryonic development was discovered when genetic mutations in Wnt pathway proteins produced abnormal fruit fly embryos. Later research found that the genes responsible for these abnormalities also influenced breast cancer development in mice. Wnt signaling also controls tissue regeneration in adult bone marrow, skin and intestine.

This pathway's clinical importance was demonstrated by mutations that lead to various diseases, including breast and prostate cancer, glioblastoma, type II diabetes and others. In recent years, researchers reported first successful use of Wnt pathway inhibitors in mouse models of disease.

History and etymology

The discovery of Wnt signaling was influenced by research on oncogenic (cancer-causing) retroviruses. In 1982, Roel Nusse and Harold Varmus infected mice with mouse mammary tumor virus in order to mutate mouse genes to see which mutated genes could cause breast tumors. They identified a new mouse proto-oncogene that they named int1 (integration 1).

Int1 is highly conserved across multiple species, including humans and Drosophila. Its presence in D. melanogaster led researchers to discover in 1987 that the int1 gene in Drosophila was actually the already known and characterized Drosophila gene known as Wingless (Wg). Since previous research by Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric Wieschaus (which won them the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995) had already established the function of Wg as a segment polarity gene involved in the formation of the body axis during embryonic development, researchers determined that the mammalian int1 discovered in mice is also involved in embryonic development.

Continued research led to the discovery of further int1-related genes; however, because those genes were not identified in the same manner as int1, the int gene nomenclature was inadequate. Thus, the int/Wingless family became the Wnt family and int1 became Wnt1. The name Wnt is a portmanteau of int and Wg and stands for "Wingless-related integration site".

Proteins

Wnt comprises a diverse family of secreted lipid-modified signaling glycoproteins that are 350–400 amino acids in length. The lipid modification of all Wnts is palmitoleoylation of a single totally conserved cysteine residue. Palmitoleoylation is necessary because it is required for Wnt to bind to its carrier protein Wntless (WLS) so it can be transported to the plasma membrane for secretion and it allows the Wnt protein to bind its receptor Frizzled Wnt proteins also undergo glycosylation, which attaches a carbohydrate in order to ensure proper secretion. In Wnt signaling, these proteins act as ligands to activate the different Wnt pathways via paracrine and autocrine routes.

These proteins are highly conserved across species. They can be found in mice, humans, Xenopus, zebrafish, Drosophila and many others.

| Species | Wnt proteins |

|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | WNT1, WNT2, WNT2B, WNT3, WNT3A, WNT4, WNT5A, WNT5B, WNT6, WNT7A, WNT7B, WNT8A, WNT8B, WNT9A, WNT9B, WNT10A, WNT10B, WNT11, WNT16 |

| Mus musculus (Identical proteins as in H. sapiens) | Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2B, Wnt3, Wnt3A, Wnt4, Wnt5A, Wnt5B, Wnt6, Wnt7A, Wnt7B, Wnt8A, Wnt8B, Wnt9A, Wnt9B, Wnt10A, Wnt10B, Wnt11, Wnt16 |

| Xenopus | Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2B, Wnt3, Wnt3A, Wnt4, Wnt5A, Wnt5B, Wnt7A, Wnt7B, Wnt8A, Wnt8B, Wnt10A, Wnt10B, Wnt11, Wnt11R |

| Danio rerio | Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2B, Wnt3, Wnt3A, Wnt4, Wnt5A, Wnt5B, Wnt6, Wnt7A, Wnt7B, Wnt8A, Wnt8B, Wnt10A, Wnt10B, Wnt11, Wnt16 |

| Drosophila | Wg, DWnt2, DWnt3/5, DWnt 4, DWnt6, WntD/DWnt8, DWnt10 |

| Hydra | hywnt1, hywnt5a, hywnt8, hywnt7, hywnt9/10a, hywnt9/10b, hywnt9/10c, hywnt11, hywnt16 |

| C. elegans | mom-2, lin-44, egl-20, cwn-1, cwn-2 |

Mechanism

Foundation

Wnt signaling begins when a Wnt protein binds to the N-terminal extra-cellular cysteine-rich domain of a Frizzled (Fz) family receptor. These receptors span the plasma membrane seven times and constitute a distinct family of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). However, to facilitate Wnt signaling, co-receptors may be required alongside the interaction between the Wnt protein and Fz receptor. Examples include lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)-5/6, receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), and ROR2. Upon activation of the receptor, a signal is sent to the phosphoprotein Dishevelled (Dsh), which is located in the cytoplasm. This signal is transmitted via a direct interaction between Fz and Dsh. Dsh proteins are present in all organisms and they all share the following highly conserved protein domains: an amino-terminal DIX domain, a central PDZ domain, and a carboxy-terminal DEP domain. These different domains are important because after Dsh, the Wnt signal can branch off into multiple pathways and each pathway interacts with a different combination of the three domains.

Canonical and noncanonical pathways

The three best characterized Wnt signaling pathways are the canonical Wnt pathway, the noncanonical planar cell polarity pathway, and the noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway. As their names suggest, these pathways belong to one of two categories: canonical or noncanonical. The difference between the categories is that a canonical pathway involves the protein beta-catenin (β-catenin) while a noncanonical pathway operates independently of it.

Canonical pathway

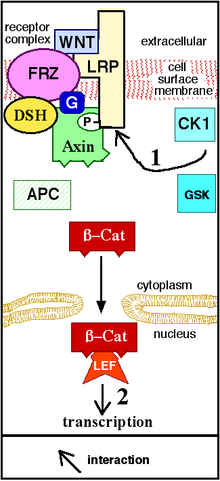

The canonical Wnt pathway (or Wnt/β-catenin pathway) is the Wnt pathway that causes an accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm and its eventual translocation into the nucleus to act as a transcriptional coactivator of transcription factors that belong to the TCF/LEF family. Without Wnt, β-catenin would not accumulate in the cytoplasm since a destruction complex would normally degrade it. This destruction complex includes the following proteins: Axin, adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC), protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) and casein kinase 1α (CK1α). It degrades β-catenin by targeting it for ubiquitination, which subsequently sends it to the proteasome to be digested. However, as soon as Wnt binds Fz and LRP5/6, the destruction complex function becomes disrupted. This is due to Wnt causing the translocation of the negative Wnt regulator, Axin, and the destruction complex to the plasma membrane. Phosphorylation by other proteins in the destruction complex subsequently binds Axin to the cytoplasmic tail of LRP5/6. Axin becomes de-phosphorylated and its stability and levels decrease. Dsh then becomes activated via phosphorylation and its DIX and PDZ domains inhibit the GSK3 activity of the destruction complex. This allows β-catenin to accumulate and localize to the nucleus and subsequently induce a cellular response via gene transduction alongside the TCF/LEF (T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancing factor) transcription factors. β-catenin recruits other transcriptional coactivators, such as BCL9, Pygopus and Parafibromin/Hyrax. The complexity of the transcriptional complex assembled by β-catenin is beginning to emerge thanks to new high-throughput proteomics studies. However, a unified theory of how β‐catenin drives target gene expression is still missing, and tissue-specific players might assist β‐catenin to define its target genes. The extensivity of the β-catenin interacting proteins complicates our understanding: β-catenin may be directly phosphorylated at Ser552 by Akt, which causes its disassociation from cell-cell contacts and accumulation in cytosol, thereafter 14-3-3ζ interacts with β-catenin (pSer552) and enhances its nuclear translocation. BCL9 and Pygopus have been reported, in fact, to possess several β-catenin-independent functions (therefore, likely, Wnt signaling-independent).

Noncanonical pathways

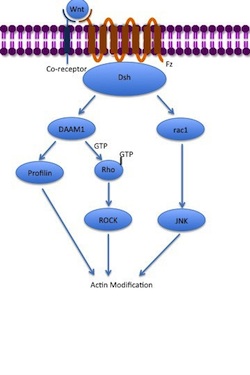

The noncanonical planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway does not involve β-catenin. It does not use LRP-5/6 as its co-receptor and is thought to use NRH1, Ryk, PTK7 or ROR2. The PCP pathway is activated via the binding of Wnt to Fz and its co-receptor. The receptor then recruits Dsh, which uses its PDZ and DIX domains to form a complex with Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (DAAM1). Daam1 then activates the small G-protein Rho through a guanine exchange factor. Rho activates Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), which is one of the major regulators of the cytoskeleton. Dsh also forms a complex with rac1 and mediates profilin binding to actin. Rac1 activates JNK and can also lead to actin polymerization. Profilin binding to actin can result in restructuring of the cytoskeleton and gastrulation.

The noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway also does not involve β-catenin. Its role is to help regulate calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in order to control intracellular calcium levels. Like other Wnt pathways, upon ligand binding, the activated Fz receptor directly interacts with Dsh and activates specific Dsh-protein domains. The domains involved in Wnt/calcium signaling are the PDZ and DEP domains. However, unlike other Wnt pathways, the Fz receptor directly interfaces with a trimeric G-protein. This co-stimulation of Dsh and the G-protein can lead to the activation of either PLC or cGMP-specific PDE. If PLC is activated, the plasma membrane component PIP2 is cleaved into DAG and IP3. When IP3 binds its receptor on the ER, calcium is released. Increased concentrations of calcium and DAG can activate Cdc42 through PKC. Cdc42 is an important regulator of ventral patterning. Increased calcium also activates calcineurin and CaMKII. CaMKII induces activation of the transcription factor NFAT, which regulates cell adhesion, migration and tissue separation. Calcineurin activates TAK1 and NLK kinase, which can interfere with TCF/β-Catenin signaling in the canonical Wnt pathway. However, if PDE is activated, calcium release from the ER is inhibited. PDE mediates this through the inhibition of PKG, which subsequently causes the inhibition of calcium release.

Integrated Wnt Pathway

The binary distinction of canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways has come under scrutiny and an integrated, convergent Wnt pathway has been proposed. Some evidence for this was found for one Wnt ligand (Wnt5A). Evidence for a convergent Wnt signaling pathway that shows integrated activation of Wnt/Ca2+ and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, for multiple Wnt ligands, was described in mammalian cell lines.

Other pathways

Wnt signaling also regulates a number of other signaling pathways that have not been as extensively elucidated. One such pathway includes the interaction between Wnt and GSK3. During cell growth, Wnt can inhibit GSK3 in order to activate mTOR in the absence of β-catenin. However, Wnt can also serve as a negative regulator of mTOR via activation of the tumor suppressor TSC2, which is upregulated via Dsh and GSK3 interaction. During myogenesis, Wnt uses PA and CREB to activate MyoD and Myf5 genes. Wnt also acts in conjunction with Ryk and Src to allow for regulation of neuron repulsion during axonal guidance. Wnt regulates gastrulation when CK1 serves as an inhibitor of Rap1-ATPase in order to modulate the cytoskeleton during gastrulation. Further regulation of gastrulation is achieved when Wnt uses ROR2 along with the CDC42 and JNK pathway to regulate the expression of PAPC. Dsh can also interact with aPKC, Pa3, Par6 and LGl in order to control cell polarity and microtubule cytoskeleton development. While these pathways overlap with components associated with PCP and Wnt/Calcium signaling, they are considered distinct pathways because they produce different responses.

Regulation

In order to ensure proper functioning, Wnt signaling is constantly regulated at several points along its signaling pathways. For example, Wnt proteins are palmitoylated. The protein porcupine mediates this process, which means that it helps regulate when the Wnt ligand is secreted by determining when it is fully formed. Secretion is further controlled with proteins such as GPR177 (wntless) and evenness interrupted and complexes such as the retromer complex.

Upon secretion, the ligand can be prevented from reaching its receptor through the binding of proteins such as the stabilizers Dally and glypican 3 (GPC3), which inhibit diffusion. In cancer cells, both the heparan sulfate chains and the core protein of GPC3 are involved in regulating Wnt binding and activation for cell proliferation. Wnt recognizes a heparan sulfate structure on GPC3, which contains IdoA2S and GlcNS6S, and the 3-O-sulfation in GlcNS6S3S enhances the binding of Wnt to the heparan sulfate glypican. A cysteine-rich domain at the N-lobe of GPC3 has been identified to form a Wnt-binding hydrophobic groove including phenylalanine-41 that interacts with Wnt. Blocking the Wnt binding domain using a nanobody called HN3 can inhibit Wnt activation.

At the Fz receptor, the binding of proteins other than Wnt can antagonize signaling. Specific antagonists include Dickkopf (Dkk), Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (WIF-1), secreted Frizzled-related proteins (SFRP), Cerberus, Frzb, Wise, SOST, and Naked cuticle. These constitute inhibitors of Wnt signaling. However, other molecules also act as activators. Norrin and R-Spondin2 activate Wnt signaling in the absence of Wnt ligand.

Interactions between Wnt signaling pathways also regulate Wnt signaling. As previously mentioned, the Wnt/calcium pathway can inhibit TCF/β-catenin, preventing canonical Wnt pathway signaling. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is an essential activator of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Interaction of PGE2 with its receptors E2/E4 stabilizes β-catenin through cAMP/PKA mediated phosphorylation. The synthesis of PGE2 is necessary for Wnt signaling mediated processes such as tissue regeneration and control of stem cell population in zebrafish and mouse. Intriguingly, the unstructured regions of several oversized intrinsically disordered proteins play crucial roles in regulating Wnt signaling.

Induced cell responses

Embryonic development

Wnt signaling plays a critical role in embryonic development. It operates in both vertebrates and invertebrates, including humans, frogs, zebrafish, C. elegans, Drosophila and others. It was first found in the segment polarity of Drosophila, where it helps to establish anterior and posterior polarities. It is implicated in other developmental processes. As its function in Drosophila suggests, it plays a key role in body axis formation, particularly the formation of the anteroposterior and dorsoventral axes. It is involved in the induction of cell differentiation to prompt formation of important organs such as lungs and ovaries. Wnt further ensures the development of these tissues through proper regulation of cell proliferation and migration. Wnt signaling functions can be divided into axis patterning, cell fate specification, cell proliferation and cell migration.

Axis patterning

In early embryo development, the formation of the primary body axes is a crucial step in establishing the organism's overall body plan. The axes include the anteroposterior axis, dorsoventral axis, and right-left axis. Wnt signaling is implicated in the formation of the anteroposterior and dorsoventral (DV) axes. Wnt signaling activity in anterior-posterior development can be seen in mammals, fish and frogs. In mammals, the primitive streak and other surrounding tissues produce the morphogenic compounds Wnts, BMPs, FGFs, Nodal and retinoic acid to establish the posterior region during late gastrula. These proteins form concentration gradients. Areas of highest concentration establish the posterior region while areas of lowest concentration indicate the anterior region. In fish and frogs, β-catenin produced by canonical Wnt signaling causes the formation of organizing centers, which, alongside BMPs, elicit posterior formation. Wnt involvement in DV axis formation can be seen in the activity of the formation of the Spemann organizer, which establishes the dorsal region. Canonical Wnt signaling β-catenin production induces the formation of this organizer via the activation of the genes twin and siamois. Similarly, in avian gastrulation, cells of the Koller's sickle express different mesodermal marker genes that allow for the differential movement of cells during the formation of the primitive streak. Wnt signaling activated by FGFs is responsible for this movement.

Wnt signaling is also involved in the axis formation of specific body parts and organ systems later in development. In vertebrates, sonic hedgehog (Shh) and Wnt morphogenetic signaling gradients establish the dorsoventral axis of the central nervous system during neural tube axial patterning. High Wnt signaling establishes the dorsal region while high Shh signaling indicates the ventral region. Wnt is involved in the DV formation of the central nervous system through its involvement in axon guidance. Wnt proteins guide the axons of the spinal cord in an anterior-posterior direction. Wnt is also involved in the formation of the limb DV axis. Specifically, Wnt7a helps produce the dorsal patterning of the developing limb.

In the embryonic differentiation waves model of development Wnt plays a critical role as part a signalling complex in competent cells ready to differentiate. Wnt reacts to the activity of the cytoskeleton, stabilizing the initial change created by a passing wave of contraction or expansion and simultaneously signals the nucleus through the use of its different signalling pathways as to which wave the individual cell has participated in. Wnt activity thereby amplifies mechanical signalling that occurs during development.

Cell fate specification

Cell fate specification or cell differentiation is a process where undifferentiated cells can become a more specialized cell type. Wnt signaling induces differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into mesoderm and endoderm progenitor cells. These progenitor cells further differentiate into cell types such as endothelial, cardiac and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Wnt signaling induces blood formation from stem cells. Specifically, Wnt3 leads to mesoderm committed cells with hematopoietic potential. Wnt1 antagonizes neural differentiation and is a major factor in self-renewal of neural stem cells. This allows for regeneration of nervous system cells, which is further evidence of a role in promoting neural stem cell proliferation. Wnt signaling is involved in germ cell determination, gut tissue specification, hair follicle development, lung tissue development, trunk neural crest cell differentiation, nephron development, ovary development and sex determination. Wnt signaling also antagonizes heart formation, and Wnt inhibition was shown to be a critical inducer of heart tissue during development, and small molecule Wnt inhibitors are routinely used to produce cardiomyocytes from pluripotent stem cells.

Cell proliferation

In order to have the mass differentiation of cells needed to form the specified cell tissues of different organisms, proliferation and growth of embryonic stem cells must take place. This process is mediated through canonical Wnt signaling, which increases nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin. Increased β-catenin can initiate transcriptional activation of proteins such as cyclin D1 and c-myc, which control the G1 to S phase transition in the cell cycle. Entry into the S phase causes DNA replication and ultimately mitosis, which are responsible for cell proliferation. This proliferation increase is directly paired with cell differentiation because as the stem cells proliferate, they also differentiate. This allows for overall growth and development of specific tissue systems during embryonic development. This is apparent in systems such as the circulatory system where Wnt3a leads to proliferation and expansion of hematopoietic stem cells needed for red blood cell formation.

The biochemistry of cancer stem cells is subtly different from that of other tumor cells. These so-called Wnt-addicted cells hijack and depend on constant stimulation of the Wnt pathway to promote their uncontrolled growth, survival and migration. In cancer, Wnt signaling can become independent of regular stimuli, through mutations in downstream oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that become permanently activated even though the normal receptor has not received a signal. β-catenin binds to transcription factors such as the protein TCF4 and in combination the molecules activate the necessary genes. LF3 strongly inhibits this binding in vitro, in cell lines and reduced tumor growth in mouse models. It prevented replication and reduced their ability to migrate, all without affecting healthy cells. No cancer stem cells remained after treatment. The discovery was the product of "rational drug design", involving AlphaScreens and ELISA technologies.

Cell migration

Cell migration during embryonic development allows for the establishment of body axes, tissue formation, limb induction and several other processes. Wnt signaling helps mediate this process, particularly during convergent extension. Signaling from both the Wnt PCP pathway and canonical Wnt pathway is required for proper convergent extension during gastrulation. Convergent extension is further regulated by the Wnt/calcium pathway, which blocks convergent extension when activated. Wnt signaling also induces cell migration in later stages of development through the control of the migration behavior of neuroblasts, neural crest cells, myocytes, and tracheal cells.

Wnt signaling is involved in another key migration process known as the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). This process allows epithelial cells to transform into mesenchymal cells so that they are no longer held in place at the laminin. It involves cadherin down-regulation so that cells can detach from laminin and migrate. Wnt signaling is an inducer of EMT, particularly in mammary development.

Insulin sensitivity

Insulin is a peptide hormone involved in glucose homeostasis within certain organisms. Specifically, it leads to upregulation of glucose transporters in the cell membrane in order to increase glucose uptake from the bloodstream. This process is partially mediated by activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which can increase a cell's insulin sensitivity. In particular, Wnt10b is a Wnt protein that increases this sensitivity in skeletal muscle cells.

Clinical implications

Cancer

Since its initial discovery, Wnt signaling has had an association with cancer. When Wnt1 was discovered, it was first identified as a proto-oncogene in a mouse model for breast cancer. The fact that Wnt1 is a homolog of Wg shows that it is involved in embryonic development, which often calls for rapid cell division and migration. Misregulation of these processes can lead to tumor development via excess cell proliferation.

Canonical Wnt pathway activity is involved in the development of benign and malignant breast tumors. The role of Wnt pathway in tumor chemoresistance has been also well documented, as well as its role in the maintenance of a distinct subpopulation of cancer-initiating cells. Its presence is revealed by elevated levels of β-catenin in the nucleus and/or cytoplasm, which can be detected with immunohistochemical staining and Western blotting. Increased β-catenin expression is correlated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. This accumulation may be due to factors such as mutations in β-catenin, deficiencies in the β-catenin destruction complex, most frequently by mutations in structurally disordered regions of APC, overexpression of Wnt ligands, loss of inhibitors and/or decreased activity of regulatory pathways (such as the Wnt/calcium pathway). Breast tumors can metastasize due to Wnt involvement in EMT. Research looking at metastasis of basal-like breast cancer to the lungs showed that repression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling can prevent EMT, which can inhibit metastasis.

Wnt signaling has been implicated in the development of other cancers as well as in desmoid fibromatosis. Changes in CTNNB1 expression, which is the gene that encodes β-catenin, can be measured in breast, colorectal, melanoma, prostate, lung, and other cancers. Increased expression of Wnt ligand-proteins such as Wnt1, Wnt2 and Wnt7A were observed in the development of glioblastoma, oesophageal cancer and ovarian cancer respectively. Other proteins that cause multiple cancer types in the absence of proper functioning include ROR1, ROR2, SFRP4, Wnt5A, WIF1 and those of the TCF/LEF family. Wnt signaling is further implicated in the pathogenesis of bone metastasis from breast and prostate cancer with studies suggesting discrete on and off states. Wnt is down-regulated during the dormancy stage by autocrine DKK1 to avoid immune surveillance, as well as during the dissemination stages by intracellular Dact1. Meanwhile Wnt is activated during the early outgrowth phase by E-selectin.

The link between PGE2 and Wnt suggests that a chronic inflammation-related increase of PGE2 may lead to activation of the Wnt pathway in different tissues, resulting in carcinogenesis.

Type II diabetes

Diabetes mellitus type 2 is a common disease that causes reduced insulin secretion and increased insulin resistance in the periphery. It results in increased blood glucose levels, or hyperglycemia, which can be fatal if untreated. Since Wnt signaling is involved in insulin sensitivity, malfunctioning of its pathway could be involved. Overexpression of Wnt5b, for instance, may increase susceptibility due to its role in adipogenesis, since obesity and type II diabetes have high comorbidity. Wnt signaling is a strong activator of mitochondrial biogenesis. This leads to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) known to cause DNA and cellular damage. This ROS-induced damage is significant because it can cause acute hepatic insulin resistance, or injury-induced insulin resistance. Mutations in Wnt signaling-associated transcription factors, such as TCF7L2, are linked to increased susceptibility.

See also

- AXIN1

- GSK-3

- Management of hair loss

- Wingless localisation element 3 (WLE3)

- WNT1-inducible-signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1)

- WNT1-inducible-signaling pathway protein 2 (WISP2)

- WNT1-inducible-signaling pathway protein 3 (WISP3)

References

- Nusse R, Brown A, Papkoff J, Scambler P, Shackleford G, McMahon A, et al. (January 1991). "A new nomenclature for int-1 and related genes: the Wnt gene family". Cell. 64 (2): 231. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90633-a. PMID 1846319. S2CID 3189574.

- ^ Nusse R, Varmus HE (June 1992). "Wnt genes". Cell. 69 (7): 1073–87. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90630-U. PMID 1617723. S2CID 10422968.

- ^ Nusse R (January 2005). "Wnt signaling in disease and in development". Cell Research. 15 (1): 28–32. doi:10.1038/sj.cr.7290260. PMID 15686623.

- Zhang H, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Ng SS, Ren F, Wang Y, Duan Y, Chen L, Zhai Y, Guo Q, Chang Z (November 2010). "Dishevelled-DEP domain interacting protein (DDIP) inhibits Wnt signaling by promoting TCF4 degradation and disrupting the TCF4/beta-catenin complex". Cellular Signalling. 22 (11): 1753–60. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.06.016. PMID 20603214.

- ^ Goessling W, North TE, Loewer S, Lord AM, Lee S, Stoick-Cooper CL, Weidinger G, Puder M, Daley GQ, Moon RT, Zon LI (March 2009). "Genetic interaction of PGE2 and Wnt signaling regulates developmental specification of stem cells and regeneration". Cell. 136 (6): 1136–47. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.015. PMC 2692708. PMID 19303855.

- Logan CY, Nusse R (2004). "The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 20: 781–810. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.322.311. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. PMID 15473860.

- ^ Komiya Y, Habas R (April 2008). "Wnt signal transduction pathways". Organogenesis. 4 (2): 68–75. doi:10.4161/org.4.2.5851. PMC 2634250. PMID 19279717.

- Zimmerli D, Hausmann G, Cantù C, Basler K (December 2017). "Pharmacological interventions in the Wnt pathway: inhibition of Wnt secretion versus disrupting the protein-protein interfaces of nuclear factors". British Journal of Pharmacology. 174 (24): 4600–4610. doi:10.1111/bph.13864. PMC 5727313. PMID 28521071.

- Nusse R, van Ooyen A, Cox D, Fung YK, Varmus H (1984). "Mode of proviral activation of a putative mammary oncogene (int-1) on mouse chromosome 15". Nature. 307 (5947): 131–6. Bibcode:1984Natur.307..131N. doi:10.1038/307131a0. PMID 6318122. S2CID 4261052.

- Klaus A, Birchmeier W (May 2008). "Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 8 (5): 387–98. doi:10.1038/nrc2389. PMID 18432252. S2CID 31382024.

- Cadigan KM, Nusse R (December 1997). "Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development". Genes & Development. 11 (24): 3286–305. doi:10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. PMID 9407023.

- Hannoush RN (October 2015). "Synthetic protein lipidation". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 28: 39–46. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.05.025. PMID 26080277.

- Yu J, Chia J, Canning CA, Jones CM, Bard FA, Virshup DM (May 2014). "WLS retrograde transport to the endoplasmic reticulum during Wnt secretion". Developmental Cell. 29 (3): 277–91. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.016. PMID 24768165.

- Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC (July 2012). "Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled". Science. 337 (6090): 59–64. Bibcode:2012Sci...337...59J. doi:10.1126/science.1222879. PMC 3577348. PMID 22653731.

- Hosseini V, Dani C, Geranmayeh MH, Mohammadzadeh F, Nazari Soltan Ahmad S, Darabi M (June 2019). "Wnt lipidation: Roles in trafficking, modulation, and function". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 234 (6): 8040–8054. doi:10.1002/jcp.27570. PMID 30341908. S2CID 53009014.

- Kurayoshi M, Yamamoto H, Izumi S, Kikuchi A (March 2007). "Post-translational palmitoylation and glycosylation of Wnt-5a are necessary for its signalling". The Biochemical Journal. 402 (3): 515–23. doi:10.1042/BJ20061476. PMC 1863570. PMID 17117926.

- Nusse, Roel. "The Wnt Homepage". Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- Sawa H, Korswagen HC (March 2013). "WNT signaling in C. Elegans". WormBook: 1–30. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.7.2. PMC 5402212. PMID 25263666.

- ^ Rao TP, Kühl M (June 2010). "An updated overview on Wnt signaling pathways: a prelude for more". Circulation Research. 106 (12): 1798–806. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.219840. PMID 20576942.

- Schulte G, Bryja V (October 2007). "The Frizzled family of unconventional G-protein-coupled receptors". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 28 (10): 518–25. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.001. PMID 17884187.

- Habas R, Dawid IB (February 2005). "Dishevelled and Wnt signaling: is the nucleus the final frontier?". Journal of Biology. 4 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/jbiol22. PMC 551522. PMID 15720723.

- Minde DP, Anvarian Z, Rüdiger SG, Maurice MM (August 2011). "Messing up disorder: how do missense mutations in the tumor suppressor protein APC lead to cancer?". Molecular Cancer. 10: 101. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-10-101. PMC 3170638. PMID 21859464.

- Minde DP, Radli M, Forneris F, Maurice MM, Rüdiger SG (2013). Buckle AM (ed.). "Large extent of disorder in Adenomatous Polyposis Coli offers a strategy to guard Wnt signalling against point mutations". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e77257. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...877257M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077257. PMC 3793970. PMID 24130866.

- ^ MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X (July 2009). "Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases". Developmental Cell. 17 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. PMC 2861485. PMID 19619488.

- Staal FJ, Clevers H (February 2000). "Tcf/Lef transcription factors during T-cell development: unique and overlapping functions". The Hematology Journal. 1 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1038/sj.thj.6200001. PMID 11920163.

- Kramps T, Peter O, Brunner E, Nellen D, Froesch B, Chatterjee S, Murone M, Züllig S, Basler K (April 2002). "Wnt/wingless signaling requires BCL9/legless-mediated recruitment of pygopus to the nuclear beta-catenin-TCF complex" (PDF). Cell. 109 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00679-7. PMID 11955446. S2CID 16720801. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K (April 2006). "Parafibromin/Hyrax activates Wnt/Wg target gene transcription by direct association with beta-catenin/Armadillo". Cell. 125 (2): 327–41. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.053. PMID 16630820.

- van Tienen LM, Mieszczanek J, Fiedler M, Rutherford TJ, Bienz M (March 2017). "Constitutive scaffolding of multiple Wnt enhanceosome components by Legless/BCL9". eLife. 6: e20882. doi:10.7554/elife.20882. PMC 5352222. PMID 28296634.

- Söderholm, Simon; Cantù, Claudio (21 October 2020). "The WNT/β-catenin dependent transcription: A tissue-specific business". WIREs Systems Biology and Medicine. 13 (3): e1511. doi:10.1002/wsbm.1511. PMC 9285942. PMID 33085215.

- Fang D, Hawke D, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Meisenhelder J, Nika H, Mills GB, Kobayashi R, Hunter T, Lu Z (April 2007). "Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by AKT promotes beta-catenin transcriptional activity". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (15): 11221–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M611871200. PMC 1850976. PMID 17287208.

- Cantù C, Valenta T, Hausmann G, Vilain N, Aguet M, Basler K (June 2013). "The Pygo2-H3K4me2/3 interaction is dispensable for mouse development and Wnt signaling-dependent transcription". Development. 140 (11): 2377–86. doi:10.1242/dev.093591. PMID 23637336.

- Cantù C, Zimmerli D, Hausmann G, Valenta T, Moor A, Aguet M, Basler K (September 2014). "Pax6-dependent, but β-catenin-independent, function of Bcl9 proteins in mouse lens development". Genes & Development. 28 (17): 1879–84. doi:10.1101/gad.246140.114. PMC 4197948. PMID 25184676.

- Cantù C, Pagella P, Shajiei TD, Zimmerli D, Valenta T, Hausmann G, Basler K, Mitsiadis TA (February 2017). "A cytoplasmic role of Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional cofactors Bcl9, Bcl9l, and Pygopus in tooth enamel formation". Science Signaling. 10 (465): eaah4598. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aah4598. PMID 28174279. S2CID 6845295.

- Gordon MD, Nusse R (August 2006). "Wnt signaling: multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (32): 22429–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.R600015200. PMID 16793760.

- Sugimura R, Li L (December 2010). "Noncanonical Wnt signaling in vertebrate development, stem cells, and diseases". Birth Defects Research. Part C, Embryo Today. 90 (4): 243–56. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20195. PMID 21181886.

- ^ van Amerongen R, Nusse R (October 2009). "Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development". Development. 136 (19): 3205–14. doi:10.1242/dev.033910. PMID 19736321. S2CID 16120512.

- van Amerongen R, Fuerer C, Mizutani M, Nusse R (September 2012). "Wnt5a can both activate and repress Wnt/β-catenin signaling during mouse embryonic development". Developmental Biology. 369 (1): 101–14. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.020. PMC 3435145. PMID 22771246.

- Thrasivoulou C, Millar M, Ahmed A (December 2013). "Activation of intracellular calcium by multiple Wnt ligands and translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus: a convergent model of Wnt/Ca2+ and Wnt/β-catenin pathways". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (50): 35651–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.437913. PMC 3861617. PMID 24158438.

- Inoki K, Ouyang H, Zhu T, Lindvall C, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yang Q, Bennett C, Harada Y, Stankunas K, Wang CY, He X, MacDougald OA, You M, Williams BO, Guan KL (September 2006). "TSC2 integrates Wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by AMPK and GSK3 to regulate cell growth". Cell. 126 (5): 955–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.055. PMID 16959574. S2CID 16047397.

- Kuroda K, Kuang S, Taketo MM, Rudnicki MA (March 2013). "Canonical Wnt signaling induces BMP-4 to specify slow myofibrogenesis of fetal myoblasts". Skeletal Muscle. 3 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/2044-5040-3-5. PMC 3602004. PMID 23497616.

- Malinauskas T, Jones EY (December 2014). "Extracellular modulators of Wnt signalling". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 29: 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2014.10.003. PMID 25460271.

- Gao W, Kim H, Feng M, Phung Y, Xavier CP, Rubin JS, Ho M (August 2014). "Inactivation of Wnt signaling by a human antibody that recognizes the heparan sulfate chains of glypican-3 for liver cancer therapy". Hepatology. 60 (2): 576–87. doi:10.1002/hep.26996. PMC 4083010. PMID 24492943.

- Gao W, Xu Y, Liu J, Ho M (May 2016). "Epitope mapping by a Wnt-blocking antibody: evidence of the Wnt binding domain in heparan sulfate". Scientific Reports. 6: 26245. Bibcode:2016NatSR...626245G. doi:10.1038/srep26245. PMC 4869111. PMID 27185050.

- Gao W, Tang Z, Zhang YF, Feng M, Qian M, Dimitrov DS, Ho M (March 2015). "Immunotoxin targeting glypican-3 regresses liver cancer via dual inhibition of Wnt signalling and protein synthesis". Nature Communications. 6: 6536. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6536G. doi:10.1038/ncomms7536. PMC 4357278. PMID 25758784.

- ^ Li N, Wei L, Liu X, Bai H, Ye Y, Li D, et al. (April 2019). "A Frizzled-Like Cysteine-Rich Domain in Glypican-3 Mediates Wnt Binding and Regulates Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor Growth in Mice". Hepatology. 70 (4): 1231–1245. doi:10.1002/hep.30646. PMC 6783318. PMID 30963603.

- Ho M, Kim H (February 2011). "Glypican-3: a new target for cancer immunotherapy". European Journal of Cancer. 47 (3): 333–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.024. PMC 3031711. PMID 21112773.

- Li N, Gao W, Zhang YF, Ho M (November 2018). "Glypicans as Cancer Therapeutic Targets". Trends in Cancer. 4 (11): 741–754. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2018.09.004. PMC 6209326. PMID 30352677.

- Gao, Wei; Xu, Yongmei; Liu, Jian; Ho, Mitchell (May 17, 2016). "Epitope mapping by a Wnt-blocking antibody: evidence of the Wnt binding domain in heparan sulfate". Scientific Reports. 6: 26245. Bibcode:2016NatSR...626245G. doi:10.1038/srep26245. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4869111. PMID 27185050.

- Kolluri A, Ho M (2019-08-02). "The Role of Glypican-3 in Regulating Wnt, YAP, and Hedgehog in Liver Cancer". Frontiers in Oncology. 9: 708. doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00708. PMC 6688162. PMID 31428581.

- Malinauskas T, Aricescu AR, Lu W, Siebold C, Jones EY (July 2011). "Modular mechanism of Wnt signaling inhibition by Wnt inhibitory factor 1". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 18 (8): 886–93. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2081. PMC 3430870. PMID 21743455.

- Malinauskas T (March 2008). "Docking of fatty acids into the WIF domain of the human Wnt inhibitory factor-1". Lipids. 43 (3): 227–30. doi:10.1007/s11745-007-3144-3. PMID 18256869. S2CID 31357937.

- ^ Minde DP, Radli M, Forneris F, Maurice MM, Rüdiger SG (2013). "Large extent of disorder in Adenomatous Polyposis Coli offers a strategy to guard Wnt signalling against point mutations". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e77257. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...877257M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077257. PMC 3793970. PMID 24130866.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2010). Developmental biology (9th ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 9780878933846.

- Vasiev B, Balter A, Chaplain M, Glazier JA, Weijer CJ (May 2010). "Modeling gastrulation in the chick embryo: formation of the primitive streak". PLOS ONE. 5 (5): e10571. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510571V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010571. PMC 2868022. PMID 20485500.

- Gilbert SF (2014). "Early Development in Birds". Developmental Biology (10th ed.). Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates.

- Ulloa F, Martí E (January 2010). "Wnt won the war: antagonistic role of Wnt over Shh controls dorso-ventral patterning of the vertebrate neural tube". Developmental Dynamics. 239 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1002/dvdy.22058. PMID 19681160.

- Zou Y (September 2004). "Wnt signaling in axon guidance". Trends in Neurosciences. 27 (9): 528–32. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.015. PMID 15331234. S2CID 15635026.

- Gordon NK, Gordon R (March 2016). "The organelle of differentiation in embryos: the cell state splitter". Theoretical Biology & Medical Modelling. 13: 11. doi:10.1186/s12976-016-0037-2. PMC 4785624. PMID 26965444.

- Gordon N, Gordon, R (2016). Embryogenesis Explained. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. pp. 580–591. doi:10.1142/8152. ISBN 978-981-4740-69-2.

- ^ Nusse R (May 2008). "Wnt signaling and stem cell control". Cell Research. 18 (5): 523–7. doi:10.1038/cr.2008.47. PMID 18392048.

- Bakre MM, Hoi A, Mong JC, Koh YY, Wong KY, Stanton LW (October 2007). "Generation of multipotential mesendodermal progenitors from mouse embryonic stem cells via sustained Wnt pathway activation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (43): 31703–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M704287200. PMID 17711862.

- Woll PS, Morris JK, Painschab MS, Marcus RK, Kohn AD, Biechele TL, Moon RT, Kaufman DS (January 2008). "Wnt signaling promotes hematoendothelial cell development from human embryonic stem cells". Blood. 111 (1): 122–31. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-04-084186. PMC 2200802. PMID 17875805.

- Schneider VA, Mercola M (February 2001). "Wnt antagonism initiates cardiogenesis in Xenopus laevis". Genes & Development. 15 (3): 304–15. doi:10.1101/gad.855601. PMC 312618. PMID 11159911.

- Marvin MJ, Di Rocco G, Gardiner A, Bush SM, Lassar AB (February 2001). "Inhibition of Wnt activity induces heart formation from posterior mesoderm". Genes & Development. 15 (3): 316–27. doi:10.1101/gad.855501. PMC 312622. PMID 11159912.

- Ueno S, Weidinger G, Osugi T, Kohn AD, Golob JL, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Moon RT, Murry CE (June 2007). "Biphasic role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiac specification in zebrafish and embryonic stem cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (23): 9685–90. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.9685U. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702859104. PMC 1876428. PMID 17522258.

- Willems E, Spiering S, Davidovics H, Lanier M, Xia Z, Dawson M, Cashman J, Mercola M (August 2011). "Small-molecule inhibitors of the Wnt pathway potently promote cardiomyocytes from human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm". Circulation Research. 109 (4): 360–4. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249540. PMC 3327303. PMID 21737789.

- Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, Lin ZC, Churko JM, Ebert AD, Lan F, Diecke S, Huber B, Mordwinkin NM, Plews JR, Abilez OJ, Cui B, Gold JD, Wu JC (August 2014). "Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes". Nature Methods. 11 (8): 855–60. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2999. PMC 4169698. PMID 24930130.

- Kaldis P, Pagano M (December 2009). "Wnt signaling in mitosis". Developmental Cell. 17 (6): 749–50. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.001. PMID 20059944.

- Willert K, Jones KA (June 2006). "Wnt signaling: is the party in the nucleus?". Genes & Development. 20 (11): 1394–404. doi:10.1101/gad.1424006. PMID 16751178.

- Hodge, Russ (2016-01-25). "Hacking the programs of cancer stem cells". medicalxpress.com. Medical Express. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- Schambony A, Wedlich D (2013). Wnt Signaling and Cell Migration. Landes Bioscience. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Micalizzi DS, Farabaugh SM, Ford HL (June 2010). "Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: parallels between normal development and tumor progression". Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 15 (2): 117–34. doi:10.1007/s10911-010-9178-9. PMC 2886089. PMID 20490631.

- Abiola M, Favier M, Christodoulou-Vafeiadou E, Pichard AL, Martelly I, Guillet-Deniau I (December 2009). "Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling increases insulin sensitivity through a reciprocal regulation of Wnt10b and SREBP-1c in skeletal muscle cells". PLOS ONE. 4 (12): e8509. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.8509A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008509. PMC 2794543. PMID 20041157.

- Milosevic, V. et al. Wnt/IL-1β/IL-8 autocrine circuitries control chemoresistance in mesothelioma initiating cells by inducing ABCB5.Int. J. Cancer, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32419

- Howe LR, Brown AM (January 2004). "Wnt signaling and breast cancer". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 3 (1): 36–41. doi:10.4161/cbt.3.1.561. PMID 14739782.

- Taketo MM (April 2004). "Shutting down Wnt signal-activated cancer". Nature Genetics. 36 (4): 320–2. doi:10.1038/ng0404-320. PMID 15054482.

- DiMeo TA, Anderson K, Phadke P, Fan C, Feng C, Perou CM, Naber S, Kuperwasser C (July 2009). "A novel lung metastasis signature links Wnt signaling with cancer cell self-renewal and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in basal-like breast cancer". Cancer Research. 69 (13): 5364–73. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4135. PMC 2782448. PMID 19549913.

- Howard, J. Harrison; Pollock, Raphael E. (June 2016). "Intra-Abdominal and Abdominal Wall Desmoid Fibromatosis". Oncology and Therapy. 4 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1007/s40487-016-0017-z. ISSN 2366-1070. PMC 5315078. PMID 28261640.

- Anastas JN, Moon RT (January 2013). "WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 13 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1038/nrc3419. PMID 23258168. S2CID 35599667.

- Malladi, Srinivas; Macalinao, Danilo G.; Jin, Xin; He, Lan; Basnet, Harihar; Zou, Yilong; de Stanchina, Elisa; Massagué, Joan (2016-03-24). "Metastatic Latency and Immune Evasion through Autocrine Inhibition of WNT". Cell. 165 (1): 45–60. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.025. ISSN 1097-4172. PMC 4808520. PMID 27015306.

- Esposito, Mark; Fang, Cao; Cook, Katelyn C.; Park, Nana; Wei, Yong; Spadazzi, Chiara; Bracha, Dan; Gunaratna, Ramesh T.; Laevsky, Gary; DeCoste, Christina J.; Slabodkin, Hannah (March 2021). "TGF-β-induced DACT1 biomolecular condensates repress Wnt signalling to promote bone metastasis". Nature Cell Biology. 23 (3): 257–267. doi:10.1038/s41556-021-00641-w. ISSN 1476-4679. PMC 7970447. PMID 33723425.

- Esposito, Mark; Mondal, Nandini; Greco, Todd M.; Wei, Yong; Spadazzi, Chiara; Lin, Song-Chang; Zheng, Hanqiu; Cheung, Corey; Magnani, John L.; Lin, Sue-Hwa; Cristea, Ileana M. (May 2019). "Bone vascular niche E-selectin induces mesenchymal–epithelial transition and Wnt activation in cancer cells to promote bone metastasis". Nature Cell Biology. 21 (5): 627–639. doi:10.1038/s41556-019-0309-2. ISSN 1476-4679. PMC 6556210. PMID 30988423.

- Welters HJ, Kulkarni RN (December 2008). "Wnt signaling: relevance to beta-cell biology and diabetes". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 19 (10): 349–55. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2008.08.004. PMID 18926717. S2CID 19299033.

- Yoon JC, Ng A, Kim BH, Bianco A, Xavier RJ, Elledge SJ (July 2010). "Wnt signaling regulates mitochondrial physiology and insulin sensitivity". Genes & Development. 24 (14): 1507–18. doi:10.1101/gad.1924910. PMC 2904941. PMID 20634317.

- Zhai L, Ballinger SW, Messina JL (March 2011). "Role of reactive oxygen species in injury-induced insulin resistance". Molecular Endocrinology. 25 (3): 492–502. doi:10.1210/me.2010-0224. PMC 3045736. PMID 21239612.

- Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, et al. (March 2006). "Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes". Nature Genetics. 38 (3): 320–3. doi:10.1038/ng1732. PMID 16415884. S2CID 28825825.

Further reading

- Milosevic V, et al. (January 2020). "Wnt/IL-1β/IL-8 autocrine circuitries control chemoresistance in mesothelioma initiating cells by inducing ABCB5". Int. J. Cancer. 146 (1): 192–207. doi:10.1002/ijc.32419. hdl:2318/1711962. PMID 31107974. S2CID 160014053.

- Dinasarapu AR, Saunders B, Ozerlat I, Azam K, Subramaniam S (June 2011). "Signaling gateway molecule pages--a data model perspective". Bioinformatics. 27 (12): 1736–8. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr190. PMC 3106186. PMID 21505029.

External links

- Wnt+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

| Cell signaling / Signal transduction | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signaling pathways | |||||||||||||

| Agents |

| ||||||||||||

| By distance | |||||||||||||

| Other concepts | |||||||||||||

| Signaling pathway: Wnt signaling pathway | |

|---|---|

| Ligand | |

| Receptor | |

| Second messenger | |