Pharmaceutical compound

Fluoxetine, sold under the brand name Prozac, among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It is used for the treatment of major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. It is also approved for treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and children 8 years of age and over. It has also been used to treat premature ejaculation. Fluoxetine is taken by mouth.

Common side effects include loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea, headache, trouble sleeping, dry mouth, and sexual dysfunction. Serious side effects include serotonin syndrome, mania, seizures, an increased risk of suicidal behavior in people under 25 years old, and an increased risk of bleeding. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is less likely to occur with fluoxetine than with other antidepressants, but it still happens in many cases. Fluoxetine taken during pregnancy is associated with a significant increase in congenital heart defects in newborns. It has been suggested that fluoxetine therapy may be continued during breastfeeding if it was used during pregnancy or if other antidepressants were ineffective.

Fluoxetine was invented by Eli Lilly and Company in 1972 and entered medical use in 1986. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is available as a generic medication. In 2022, it was the 22nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 24 million prescriptions.

Eli Lilly also markets fluoxetine in a fixed-dose combination with olanzapine as olanzapine/fluoxetine (Symbyax), which was approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of depressive episodes of bipolar I disorder in 2003 and for treatment-resistant depression in 2009.

Medical uses

Fluoxetine is frequently used to treat major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and trichotillomania. It has also been used for cataplexy, obesity, and alcohol dependence, as well as binge eating disorder. Fluoxetine seems to be ineffective for social anxiety disorder. Studies do not support a benefit in children with autism, though there is tentative evidence for its benefit in adult autism. Fluoxetine together with fluvoxamine has shown some initial promise as a potential treatment for reducing COVID-19 severity if given early.

Depression

Fluoxetine is approved for the treatment of major depression in children and adults. A meta-analysis of trials in adults concluded that fluoxetine modestly outperforms placebo. Fluoxetine may be less effective than other antidepressants, but has high acceptability.

For children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe depressive disorder, fluoxetine seems to be the best treatment (either with or without cognitive behavioural therapy, although fluoxetine alone does not appear to be superior to CBT alone) but more research is needed to be certain, as effect sizes are small and the existing evidence is of dubious quality. A 2022 systematic review and trial restoration of the two original blinded-control trials used to approve the use of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression found that both of the trials were severely flawed, and therefore did not demonstrate the safety or efficacy of the medication.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Fluoxetine is effective in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) for adults. It is also effective for treating OCD in children and adolescents. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry state that SSRIs, including fluoxetine, should be used as first-line therapy in children, along with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for the treatment of moderate to severe OCD.

Panic disorder

The efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of panic disorder was demonstrated in two 12-week randomized multicenter phase III clinical trials that enrolled patients diagnosed with panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. In the first trial, 42% of subjects in the fluoxetine-treated arm were free of panic attacks at the end of the study, vs. 28% in the placebo arm. In the second trial, 62% of fluoxetine-treated patients were free of panic attacks at the end of the study, vs. 44% in the placebo arm.

Bulimia nervosa

A 2011 systematic review discussed seven trials that compared fluoxetine to a placebo in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, six of which found a statistically significant reduction in symptoms such as vomiting and binge eating. However, no difference was observed between treatment arms when fluoxetine and psychotherapy were compared to psychotherapy alone.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Fluoxetine is used to treat premenstrual dysphoric disorder, a condition where individuals have affective and somatic symptoms monthly during the luteal phase of menstruation. Taking fluoxetine 20 mg/d can be effective in treating PMDD, though doses of 10 mg/d have also been prescribed effectively.

Impulsive aggression

Fluoxetine is considered a first-line medication for the treatment of impulsive aggression of low intensity. Fluoxetine reduced low-intensity aggressive behavior in patients in intermittent aggressive disorder and borderline personality disorder. Fluoxetine also reduced acts of domestic violence in alcoholics with a history of such behavior.

Obesity and overweight adults

In 2019 a systematic review compared the effects on weight of various doses of fluoxetine (60 mg/d, 40 mg/d, 20 mg/d, 10 mg/d) in obese and overweight adults. When compared to placebo, all dosages of fluoxetine appeared to contribute to weight loss but lead to increased risk of experiencing side effects, such as dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, insomnia, and nausea, during the period of treatment. However, these conclusions were from low-certainty evidence. When comparing, in the same review, the effects of fluoxetine on the weight of obese and overweight adults, to other anti-obesity agents, omega-3 gel capsule and not receiving treatment, the authors could not reach conclusive results due to poor quality of evidence.

Special populations

In children and adolescents, fluoxetine is the antidepressant of choice due to tentative evidence favoring its efficacy and tolerability. Evidence supporting an increased risk of major fetal malformations resulting from fluoxetine exposure is limited, although the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) of the United Kingdom has warned prescribers and patients of the potential for fluoxetine exposure in the first trimester (during organogenesis, formation of the fetal organs) to cause a slight increase in the risk of congenital cardiac malformations in the newborn. Furthermore, an association between fluoxetine use during the first trimester and an increased risk of minor fetal malformations was observed in one study.

However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies – published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada – concluded, "the apparent increased risk of fetal cardiac malformations associated with maternal use of fluoxetine has recently been shown also in depressed women who deferred SSRI therapy in pregnancy, and therefore most probably reflects an ascertainment bias. Overall, women who are treated with fluoxetine during the first trimester of pregnancy do not appear to have an increased risk of major fetal malformations."

Per the FDA, infants exposed to SSRIs in late pregnancy may have an increased risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Limited data support this risk, but the FDA recommends physicians consider tapering SSRIs such as fluoxetine during the third trimester. A 2009 review recommended against fluoxetine as a first-line SSRI during lactation, stating, "Fluoxetine should be viewed as a less-preferred SSRI for breastfeeding mothers, particularly with newborn infants, and in those mothers who consumed fluoxetine during gestation." Sertraline is often the preferred SSRI during pregnancy due to the relatively minimal fetal exposure observed and its safety profile while breastfeeding.

Adverse effects

Side effects observed in fluoxetine-treated persons in clinical trials with an incidence >5% and at least twice as common in fluoxetine-treated persons compared to those who received a placebo pill include abnormal dreams, abnormal ejaculation, anorexia, anxiety, asthenia, diarrhea, dizziness, dry mouth, dyspepsia, fatigue, flu syndrome, impotence, insomnia, decreased libido, nausea, nervousness, pharyngitis, rash, sinusitis, somnolence, sweating, tremor, vasodilation, and yawning. Fluoxetine is considered the most stimulating of the SSRIs (that is, it is most prone to causing insomnia and agitation). It also appears to be the most prone of the SSRIs for producing dermatologic reactions (e.g. urticaria (hives), rash, itchiness, etc.).

Sexual dysfunction

See also: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor § Sexual dysfunctionSexual dysfunction, including loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, lack of vaginal lubrication, and anorgasmia, are some of the most commonly encountered adverse effects of treatment with fluoxetine and other SSRIs. While early clinical trials suggested a relatively low rate of sexual dysfunction, more recent studies in which the investigator actively inquires about sexual problems suggest that the incidence is >70%.

In 2019, the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee of the European Medicines Agency recommended that packaging leaflets of selected SSRIs and SNRIs should be amended to include information regarding a possible risk of persistent sexual dysfunction. Following on the European assessment, a safety review by Health Canada "could neither confirm nor rule out a causal link ... which was long lasting in rare cases", but recommended that "healthcare professionals inform patients about the potential risk of long-lasting sexual dysfunction despite discontinuation of treatment".

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome

Fluoxetine's longer half-life makes it less common to develop antidepressant discontinuation syndrome following cessation of therapy, especially when compared with antidepressants with shorter half-lives such as paroxetine. Although gradual dose reductions are recommended with antidepressants with shorter half-lives, tapering may not be necessary with fluoxetine.

Pregnancy

Antidepressant exposure (including fluoxetine) is associated with shorter average duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g), and lower Apgar scores (by <0.4 points). There is 30–36% increase in congenital heart defects among children whose mothers were prescribed fluoxetine during pregnancy, with fluoxetine use in the first trimester associated with 38–65% increase in septal heart defects.

Suicide

| This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (March 2022) |

On 14 September 1989, Joseph T. Wesbecker killed eight people and injured twelve before committing suicide. His relatives and victims blamed his actions on the Fluoxetine he had begun taking 11 days previously. Eli Lilly settled the case. The incident set off a chain of lawsuits and public outcries, resulting in Eli Lilly paying out $50 million across 300 claims. Eli Lilly was accused of not doing enough to warn patients and doctors about the adverse effects, which it had described as "activation", years before the incident. It was revealed in a lawsuit by the family of Bill Forsyth Sr, who killed his wife and then himself on 11 March 1993, that the Federal Health Agency (BGA) in the Federal Republic of Germany had refused to license Fluoxetine after examination of internal Eli Lilly documents there had been 16 suicide attempts, two of which had been successful, during clinical trials. The BGA considered that Fluoxetine administration was causative because those considered to be at risk of suicide were not allowed to participate in the trial. On the basis of the internal statistical evidence engathered by Eli Lilly that emerged in this lawsuit, it was estimated by 1999 that there would have been 250,000 suicide attempts and 25,000 suicides globally.

In October 2004, the FDA added its most serious warning, a black box warning, to all antidepressant drugs regarding use in children. In 2006, the FDA included adults aged 25 or younger. Statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of FDA experts found a 2-fold increase of the suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, and 1.5-fold increase of suicidality in the 18–24 age group. The suicidality was slightly decreased for those older than 24, and statistically significantly lower in the 65 and older group. In February 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordered an update to the warnings based on statistical evidence from twenty-four trials in which the risk of such events increased from two percent to four percent relative to the placebo trials.

A study published in May 2009 found that fluoxetine was more likely to increase overall suicidal behavior. 14.7% of the patients (n=44) on Fluoxetine had suicidal events, compared to 6.3% in the psychotherapy group and 8.4% from the combined treatment group. Similarly, the analysis conducted by the UK MHRA found a 50% increase in suicide-related events, not reaching statistical significance, in the children and adolescents on fluoxetine as compared to the ones on placebo. According to the MHRA data, fluoxetine did not change the rate of self-harm in adults and statistically significantly decreased suicidal ideation by 50%.

QT prolongation

Fluoxetine can affect the electrical currents that heart muscle cells use to coordinate their contraction, specifically the potassium currents Ito and IKs that repolarise the cardiac action potential. Under certain circumstances, this can lead to prolongation of the QT interval, a measurement made on an electrocardiogram reflecting how long it takes for the heart to electrically recharge after each heartbeat. When fluoxetine is taken alongside other drugs that prolong the QT interval, or by those with a susceptibility to long QT syndrome, there is a small risk of potentially lethal abnormal heart rhythms such as torsades de pointes. A study completed in 2011 found that fluoxetine does not alter the QT interval and has no clinically meaningful effects on the cardiac action potential.

Overdose

See also: Serotonin syndromeIn overdose, most frequent adverse effects include:

|

Nervous system effects

|

Gastrointestinal effects

|

Other effects

|

Interactions

Contraindications include prior treatment (within the past 5–6 weeks, depending on the dose) with MAOIs such as phenelzine and tranylcypromine, due to the potential for serotonin syndrome. Its use should also be avoided in those with known hypersensitivities to fluoxetine or any of the other ingredients in the formulation used. Its use in those concurrently receiving pimozide or thioridazine is also advised against.

In case of short-term administration of codeine for pain management, it is advised to monitor and adjust dosage. Codeine might not provide sufficient analgesia when fluoxetine is co-administered. If opioid treatment is required, oxycodone use should be monitored since oxycodone is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system and fluoxetine and paroxetine are potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 enzymes. This means combinations of codeine or oxycodone with fluoxetine antidepressant may lead to reduced analgesia.

In some cases, use of dextromethorphan-containing cold and cough medications with fluoxetine is advised against, due to fluoxetine increasing serotonin levels, as well as the fact that fluoxetine is a cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor, which causes dextromethorphan to not be metabolized at a normal rate, thus increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome and other potential side effects of dextromethorphan.

Patients who are taking NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E, and garlic supplements must be careful when taking fluoxetine or other SSRIs, as they can sometimes increase the blood-thinning effects of these medications.

Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine inhibit many isozymes of the cytochrome P450 system that are involved in drug metabolism. Both are potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 (which is also the chief enzyme responsible for their metabolism) and CYP2C19, and mild to moderate inhibitors of CYP2B6 and CYP2C9. In vivo, fluoxetine and norfluoxetine do not significantly affect the activity of CYP1A2 and CYP3A4. They also inhibit the activity of P-glycoprotein, a type of membrane transport protein that plays an important role in drug transport and metabolism and hence P-glycoprotein substrates, such as loperamide, may have their central effects potentiated. This extensive effect on the body's pathways for drug metabolism creates the potential for interactions with many commonly used drugs.

Its use should also be avoided in those receiving other serotonergic drugs such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, methamphetamine, amphetamine, MDMA, triptans, buspirone, ginseng, dextromethorphan (DXM), linezolid, tramadol, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and other SSRIs due to the potential for serotonin syndrome to develop as a result.

Fluoxetine may also increase the risk of opioid overdose in some instances, in part due to its inhibitory effect on cytochrome P-450. Similar to how fluoxetine can effect the metabolization of dextromethorphan, it may cause medications like oxycodone to not be metabolized at a normal rate, thus increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome as well as resulting in an increased concentration of oxycodone in the blood, which may lead to accidental overdose. A 2022 study that examined the health insurance claims of over 2 million Americans who began taking oxycodone while using SSRIs between 2000 and 2020, found that patients taking paroxetine or fluoxetine had a 23% higher risk of overdosing on oxycodone than those using other SSRIs.

There is also the potential for interaction with highly protein-bound drugs due to the potential for fluoxetine to displace said drugs from the plasma or vice versa hence increasing serum concentrations of either fluoxetine or the offending agent.

Pharmacology

| Molecular Target |

Fluoxetine | Norfluoxetine |

|---|---|---|

| SERT | 1 | 19 |

| NET | 660 | 2700 |

| DAT | 4180 | 420 |

| 5-HT1A | 32400 | 13700 |

| 5-HT2A | 147 | 295 |

| 5-HT2C | 112 | 91 |

| α1 | 3800 | 3900 |

| M1 | 702-1030 | 1200 |

| M2 | 2700 | 4600 |

| M3 | 1000 | 760 |

| M4 | 2900 | 2600 |

| M5 | 2700 | 2200 |

| H1 | 3'250 | > 10'000 |

Pharmacodynamics

Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and does not appreciably inhibit norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake at therapeutic doses. It does, however, delay the reuptake of serotonin, resulting in serotonin persisting longer when it is released. Large doses in rats have been shown to induce a significant increase in synaptic norepinephrine and dopamine. Thus, dopamine and norepinephrine may contribute to the antidepressant action of fluoxetine in humans at supratherapeutic doses (60–80 mg). This effect may be mediated by 5HT2C receptors, which are inhibited by higher concentrations of fluoxetine.

Fluoxetine increases the concentration of circulating allopregnanolone, a potent GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulator, in the brain. Norfluoxetine, a primary active metabolite of fluoxetine, produces a similar effect on allopregnanolone levels in the brains of mice. Additionally, both fluoxetine and norfluoxetine are such modulators themselves, actions which may be clinically relevant.

In addition, fluoxetine has been found to act as an agonist of the σ1-receptor, with a potency greater than that of citalopram but less than that of fluvoxamine. However, the significance of this property is not fully clear. Fluoxetine also functions as a channel blocker of anoctamin 1, a calcium-activated chloride channel. A number of other ion channels, including nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and 5-HT3 receptors, are also known to be inhibited at similar concentrations.

Fluoxetine has been shown to inhibit acid sphingomyelinase, a key regulator of ceramide levels which derives ceramide from sphingomyelin.

Mechanism of action

While it is unclear how fluoxetine exerts its effect on mood, it has been suggested that fluoxetine elicits an antidepressant effect by inhibiting serotonin reuptake in the synapse by binding to the reuptake pump on the neuronal membrane to increase serotonin availability and enhance neurotransmission. Over time, this leads to a downregulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which is associated with an improvement in passive stress tolerance, and delayed downstream increase in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which may contribute to a reduction in negative affective biases. Norfluoxetine and desmethylfluoxetine are metabolites of fluoxetine and also act as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, increasing the duration of action of the drug.

Prolonged exposure to fluoxetine changes the expression of genes involved in myelination, a process that shapes brain connectivity and contributes to symptoms of psychiatric disorders. The regulation of genes involved with myelination is partially responsible for the long-term therapeutic benefits of chronic SSRI exposure.

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of fluoxetine is relatively high (72%), and peak plasma concentrations are reached in 6–8 hours. It is highly bound to plasma proteins, mostly albumin and α1-glycoprotein. Fluoxetine is metabolized in the liver by isoenzymes of the cytochrome P450 system, including CYP2D6. The role of CYP2D6 in the metabolism of fluoxetine may be clinically important, as there is great genetic variability in the function of this enzyme among people. CYP2D6 is responsible for converting fluoxetine to its only active metabolite, norfluoxetine. Both drugs are also potent inhibitors of CYP2D6.

The extremely slow elimination of fluoxetine and its active metabolite norfluoxetine from the body distinguishes it from other antidepressants. With time, fluoxetine and norfluoxetine inhibit their own metabolism, so fluoxetine elimination half-life increases from 1 to 3 days, after a single dose, to 4 to 6 days, after long-term use. Similarly, the half-life of norfluoxetine is longer (16 days) after long-term use. Therefore, the concentration of the drug and its active metabolite in the blood continues to grow through the first few weeks of treatment, and their steady concentration in the blood is achieved only after four weeks. Moreover, the brain concentration of fluoxetine and its metabolites keeps increasing through at least the first five weeks of treatment. For major depressive disorder, while onset of antidepressant action may be felt as early as 1–2 weeks, the full benefit of the current dose a patient receives is not realized for at least a month following ingestion. For example, in one 6-week study, the median time to achieving consistent response was 29 days. Likewise, complete excretion of the drug may take several weeks. During the first week after treatment discontinuation, the brain concentration of fluoxetine decreases by only 50%, The blood level of norfluoxetine four weeks after treatment discontinuation is about 80% of the level registered by the end of the first treatment week, and, seven weeks after discontinuation, norfluoxetine is still detectable in the blood.

Measurement in body fluids

Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine may be quantitated in blood, plasma, or serum to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized persons, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma fluoxetine concentrations are usually in a range of 50–500 μg/L in persons taking the drug for its antidepressant effects, 900–3000 μg/L in survivors of acute overdosage, and 1000–7000 μg/L in victims of fatal overdosage. Norfluoxetine concentrations are approximately equal to those of the parent drug during chronic therapy but may be substantially less following acute overdosage since it requires at least 1–2 weeks for the metabolite to achieve equilibrium.

History

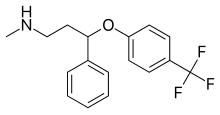

The work which eventually led to the invention of fluoxetine began at Eli Lilly and Company in 1970 as a collaboration between Bryan Molloy and Ray Fuller. It was known at that time that the antihistamine diphenhydramine showed some antidepressant-like properties. 3-Phenoxy-3-phenylpropylamine, a compound structurally similar to diphenhydramine, was taken as a starting point. Molloy and fellow Eli Lilly chemist Klaus Schmiegel synthesized a series of dozens of its derivatives. Hoping to find a derivative inhibiting only serotonin reuptake, another Eli Lilly scientist, David T. Wong, proposed to retest the series for the in vitro reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine, using a technique developed by neuroscientist Solomon Snyder. This test showed the compound later named fluoxetine to be the most potent and selective inhibitor of serotonin reuptake of the series. The first article about fluoxetine was published in 1974, following talks given at FASEB and ASPET. A year later, it was given the official chemical name fluoxetine and the Eli Lilly and Company gave it the brand name Prozac. In February 1977, Dista Products Company, a division of Eli Lilly & Company, filed an Investigational New Drug application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for fluoxetine.

Fluoxetine appeared on the Belgian market in 1986. In the U.S., the FDA gave its final approval in December 1987, and a month later Eli Lilly began marketing Prozac; annual sales in the U.S. reached $350 million within a year. Worldwide sales eventually reached a peak of $2.6 billion a year.

Lilly tried several product line extension strategies, including extended-release formulations and paying for clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in premenstrual dysphoric disorder and rebranding fluoxetine for that indication as "Sarafem" after it was approved by the FDA in 2000, following the recommendation of an advisory committee in 1999. The invention of using fluoxetine to treat PMDD was made by Richard Wurtman at MIT; the patent was licensed to his startup, Interneuron, which in turn sold it to Lilly.

To defend its Prozac revenue from generic competition, Lilly also fought a five-year, multimillion-dollar battle in court with the generic company Barr Pharmaceuticals to protect its patents on fluoxetine, and lost the cases for its line-extension patents, other than those for Sarafem, opening fluoxetine to generic manufacturers starting in 2001. When Lilly's patent expired in August 2001, generic drug competition decreased Lilly's sales of fluoxetine by 70% within two months.

In 2000 an investment bank had projected that annual sales of Sarafem could reach $250M/year. Sales of Sarafem reached about $85M/year in 2002, and in that year Lilly sold its assets connected with the drug for $295M to Galen Holdings, a small Irish pharmaceutical company specializing in dermatology and women's health that had a sales force tasked to gynecologists' offices; analysts found the deal sensible since the annual sales of Sarafem made a material financial difference to Galen, but not to Lilly.

Bringing Sarafem to market harmed Lilly's reputation in some quarters. The diagnostic category of PMDD was controversial since it was first proposed in 1987, and Lilly's role in retaining it in the appendix of the DSM-IV-TR, the discussions for which got underway in 1998, has been criticized. Lilly was criticized for inventing a disease to make money, and for not innovating but rather just seeking ways to continue making money from existing drugs. It was also criticized by the FDA and groups concerned with women's health for marketing Sarafem too aggressively when it was first launched; the campaign included a television commercial featuring a harried woman at the grocery store who asks herself if she has PMDD.

Society and culture

Prescription trends

In 2010, over 24.4 million prescriptions for generic fluoxetine were filled in the United States, making it the third-most prescribed antidepressant after sertraline and citalopram.

In 2011, 6 million prescriptions for fluoxetine were filled in the United Kingdom. Between 1998 and 2017, along with amitriptyline, it was the most commonly prescribed first antidepressant for adolescents aged 12–17 years in England.

Environmental effects

Fluoxetine has been detected in aquatic ecosystems, especially in North America. There is a growing body of research addressing the effects of fluoxetine (among other SSRIs) exposure on non-target aquatic species.

In 2003, one of the first studies addressed in detail the potential effects of fluoxetine on aquatic wildlife; this research concluded that exposure at environmental concentrations was of little risk to aquatic systems if a hazard quotient approach was applied to risk assessment. However, they also stated the need for further research addressing sub-lethal consequences of fluoxetine, specifically focusing on study species' sensitivity, behavioural responses, and endpoints modulated by the serotonin system.

Fluoxetine – similar to several other SSRIs – induces reproductive behavior in some shellfish at concentrations as low as 10 M, or 30 parts per trillion.

Since 2003, several studies have reported fluoxetine-induced impacts on many behavioural and physiological endpoints, inducing antipredator behaviour, reproduction, and foraging at or below field-detected concentrations. However, a 2014 review on the ecotoxicology of fluoxetine concluded that, at that time, a consensus on the ability of environmentally realistic dosages to affect the behaviour of wildlife could not be reached. At environmentally realistic concentrations, fluoxetine alters insect emergence timing. Richmond et al., 2019 find that at low concentrations it accelerates emergence of Diptera, while at unusually high concentrations it has no discernable effect.

Several common plants are known to absorb fluoxetine. Several crops have been tested, and Redshaw et al. 2008 find that cauliflower absorbs large amounts into the stem and leaf but not the head or root. Wu et al. 2012 find that lettuce and spinach also absorb detectable amounts, while Carter et al. 2014 find that radish (Raphanus sativus), ryegrass (Lolium perenne) – and Wu et al. 2010 find that soybean (Glycine max) – absorb little. Wu tested all tissues of soybean and all showed only low concentrations. By contrast various Reinhold et al. 2010 find duckweeds have a high uptake of fluoxetine and show promise for bioremediation of contaminated water, especially Lemna minor and Landoltia punctata. Ecotoxicity for organisms involved in aquaculture is well documented. Fluoxetine affects both aquacultured invertebrates and vertebrates, and inhibits soil microbes including a large antibacterial effect. For applications of this see § Other uses.

Politics

During the 1990 campaign for governor of Florida, it was disclosed that one of the candidates, Lawton Chiles, had depression and had resumed taking fluoxetine, leading his political opponents to question his fitness to serve as governor.

American aircraft pilots

Beginning in April 2010, fluoxetine became one of four antidepressant drugs that the FAA permitted for pilots with authorization from an aviation medical examiner. The other permitted antidepressants are sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), and escitalopram (Lexapro). These four remain the only antidepressants permitted by FAA as of 2 December 2016.

Sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram are the only antidepressants permitted for EASA medical certification, as of January 2019.

Research

The antibacterial effect described above (§ Environmental effects) could be applied against multiresistant biotypes in crop bacterial diseases and bacterial aquaculture diseases. In a glucocorticoid receptor-defective zebrafish mutant (Danio rerio) with reduced exploratory behavior, fluoxetine rescued the normal exploratory behavior. This demonstrates relationships between glucocorticoids, fluoxetine, and exploration in this fish.

Fluoxetine has an anti-nematode effect. Choy et al., 1999 founs some of this effect is due to interference with certain transmembrane proteins.

Veterinary use

Fluoxetine is commonly used and effective in treating anxiety-related behaviours and separation anxiety in dogs, especially when given as supplementation to behaviour modification.

See also

References

- Hubbard JR, Martin PR (2001). Substance Abuse in the Mentally and Physically Disabled. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8247-4497-7.

- ^ "Fluoxetine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "Mental health". Health Canada. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Prozac- fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule". DailyMed. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Sarafem (fluoxetine hydrochloride tablets ) for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 1987". DailyMed. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Prozac Fluoxetine Hydrochloride" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Eli Lilly Australia Pty. Limited. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ Altamura AC, Moro AR, Percudani M (March 1994). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 26 (3): 201–14. doi:10.2165/00003088-199426030-00004. PMID 8194283. S2CID 1406955.

- "Depressive Disorders in Children and Adolescents – Pediatrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Gao SY, Wu QJ, Sun C, Zhang TN, Shen ZQ, Liu CX, et al. (November 2018). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during early pregnancy and congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies of more than 9 million births". BMC Medicine. 16 (1): 205. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1193-5. PMC 6231277. PMID 30415641.

- ^ De Vries C, Gadzhanova S, Sykes MJ, Ward M, Roughead E (March 2021). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Considering the Risk for Congenital Heart Defects of Antidepressant Classes and Individual Antidepressants". Drug Safety. 44 (3): 291–312. doi:10.1007/s40264-020-01027-x. PMID 33354752. S2CID 229357583.

- "Fluoxetine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Myers RL (2007). The 100 most important chemical compounds: a reference guide (1st ed.). Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1.

- World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- "Fluoxetine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- "Symbyax- olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule". DailyMed. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- Grohol, J. "FDA Approves Symbyax for Treatment Resistant Depression". Psych Central Blog. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Forman-Hoffman V, Middleton JC, Feltner C, Gaynes BN, Weber RP, Bann C, et al. (17 May 2018). Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review Update (Report). Comparative Effectiveness Review. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer207. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- Hagerman RJ (16 September 1999). "Angelman Syndrome and Prader-Willi Syndrome". Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512314-2.

Dech and Budow (1991) were among the first to report the anecdotal use of fluoxetine in a case of PWS to control behavior problems, appetite, and trichotillomania.

- Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DrugPoint® System (Internet) . Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- Australian Medicines Handbook 2013. The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust; 2013.

- British National Formulary (BNF) 65. Pharmaceutical Pr; 2013.

- Husted DS, Shapira NA, Murphy TK, Mann GD, Ward HE, Goodman WK (2007). "Effect of comorbid tics on a clinically meaningful response to 8-week open-label trial of fluoxetine in obsessive compulsive disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 41 (3–4): 332–337. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.007. PMID 16860338.

- "NIMH•Eating Disorders". The National Institute of Mental Health. National Institute of Health. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Treating social anxiety disorder". Harvard Health Publishing. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Williams K, Brignell A, Randall M, Silove N, Hazell P (August 2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD004677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004677.pub3. PMID 23959778.

- Myers SM (August 2007). "The status of pharmacotherapy for autism spectrum disorders". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (11): 1579–1603. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.11.1579. PMID 17685878. S2CID 24674542.

- Doyle CA, McDougle CJ (August 2012). "Pharmacotherapy to control behavioral symptoms in children with autism". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (11): 1615–1629. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.674110. PMID 22550944. S2CID 32144885.

- Benvenuto A, Battan B, Porfirio MC, Curatolo P (February 2013). "Pharmacotherapy of autism spectrum disorders". Brain & Development. 35 (2): 119–127. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2012.03.015. PMID 22541665. S2CID 19614718.

- Mahdi M, Hermán L, Réthelyi JM, Bálint BL (March 2022). "Potential Role of the Antidepressants Fluoxetine and Fluvoxamine in the Treatment of COVID-19". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (7): 3812. doi:10.3390/ijms23073812. PMC 8998734. PMID 35409171.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- Magni LR, Purgato M, Gastaldon C, Papola D, Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, et al. (July 2013). "Fluoxetine versus other types of pharmacotherapy for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (7): CD004185. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004185.pub3. PMC 11513554. PMID 24353997.

- "Prozac may be the best treatment for young people with depression – but more research is needed". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 12 October 2020. doi:10.3310/alert_41917. S2CID 242952585.

- Zhou X, Teng T, Zhang Y, Del Giovane C, Furukawa TA, Weisz JR, et al. (July 2020). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (7): 581–601. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30137-1. PMC 7303954. PMID 32563306.

- ^ Boaden K, Tomlinson A, Cortese S, Cipriani A (2 September 2020). "Antidepressants in Children and Adolescents: Meta-Review of Efficacy, Tolerability and Suicidality in Acute Treatment". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 717. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00717. PMC 7493620. PMID 32982805.

- Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Bailey AP, Sharma V, Moller CI, Badcock PB, et al. (Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group) (May 2021). "New generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (5): CD013674. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013674.pub2. PMC 8143444. PMID 34029378.

- Gøtzsche PC, Healy D (November 2022). "Restoring the two pivotal fluoxetine trials in children and adolescents with depression". The International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine (Systematic review). 33 (4): 385–408. doi:10.3233/JRS-210034. PMID 35786661. S2CID 250241461.

- Etain B, Bonnet-Perrin E (May–June 2001). "[Value of fluoxetine in obsessive-compulsive disorder in the adult: review of the literature]". L'Encephale. 27 (3): 280–289. PMID 11488259.

- "Antidepressants for children and teenagers: what works for anxiety and depression?". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 3 November 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_53342. S2CID 253347210.

- Correll CU, Cortese S, Croatto G, Monaco F, Krinitski D, Arrondo G, et al. (June 2021). "Efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological, psychosocial, and brain stimulation interventions in children and adolescents with mental disorders: an umbrella review". World Psychiatry. 20 (2): 244–275. doi:10.1002/wps.20881. PMC 8129843. PMID 34002501.

- Geller DA, March J, et al. (The AACAP Committee on Quality Issues (CQI)) (January 2012). "Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 51 (1): 98–113. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. PMID 22176943.

- Aigner M, Treasure J, Kaye W, Kasper S (September 2011). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of eating disorders" (PDF). The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 12 (6): 400–43. doi:10.3109/15622975.2011.602720. PMID 21961502. S2CID 16733060. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2014.

- Rapkin AJ, Lewis EI (November 2013). "Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Women's Health. 9 (6): 537–56. doi:10.2217/whe.13.62. PMID 24161307.

- Carr RR, Ensom MH (April 2002). "Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (4): 713–7. doi:10.1345/aph.1A265. PMID 11918525. S2CID 37088388.

- Romano S, Judge R, Dillon J, Shuler C, Sundell K (April 1999). "The role of fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Clinical Therapeutics. 21 (4): 615–33, discussion 613. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88315-0. PMID 10363729.

- Pearlstein T, Yonkers KA (July 2002). "Review of fluoxetine and its clinical applications in premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 3 (7): 979–91. doi:10.1517/14656566.3.7.979. PMID 12083997. S2CID 9455962.

- Cohen LS, Miner C, Brown EW, Freeman E, Halbreich U, Sundell K, et al. (September 2002). "Premenstrual daily fluoxetine for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a placebo-controlled, clinical trial using computerized diaries". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 100 (3): 435–44. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02166-X. PMID 12220761. S2CID 753100.

- ^ Felthous A, Stanford M (2021). "34.The Pharmacotherapy of Impulsive Aggression in Psychopathic Disorders". In Felthous A, Sass H (eds.). The Wiley International Handbook on Psychopathic Disorders and the Law (2nd ed.). Wiley. pp. 810–13. ISBN 978-1-119-15932-2.

- Coccaro EF, Lee RJ, Kavoussi RJ (April 2009). "A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in patients with intermittent explosive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 70 (5): 653–62. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04150. PMID 19389333.

- Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ (December 1997). "Fluoxetine and impulsive aggressive behavior in personality-disordered subjects". Archives of General Psychiatry. 54 (12): 1081–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240035005. PMID 9400343.

- George DT, Phillips MJ, Lifshitz M, Lionetti TA, Spero DE, Ghassemzedeh N, et al. (January 2011). "Fluoxetine treatment of alcoholic perpetrators of domestic violence: a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled intervention study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 72 (1): 60–5. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05256gry. PMC 3026856. PMID 20673556.

- ^ Serralde-Zúñiga AE, Gonzalez Garay AG, Rodríguez-Carmona Y, Melendez G, et al. (Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group) (October 2019). "Fluoxetine for adults who are overweight or obese". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD011688. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011688.pub2. PMC 6792438. PMID 31613390.

- Taurines R, Gerlach M, Warnke A, Thome J, Wewetzer C (September 2011). "Pharmacotherapy in depressed children and adolescents". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 12 (Suppl 1): 11–5. doi:10.3109/15622975.2011.600295. PMID 21905988. S2CID 18186328.

- Cohen D (2007). "Should the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in child and adolescent depression be banned?". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 76 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1159/000096360. PMID 17170559. S2CID 1112192.

- Morrison JL, Riggs KW, Rurak DW (March 2005). "Fluoxetine during pregnancy: impact on fetal development". Reproduction, Fertility, and Development. 17 (6): 641–50. doi:10.1071/RD05030. PMID 16263070.

- ^ Brayfield A, ed. (13 August 2013). "Fluoxetine Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 24 November 2013.(subscription required)

- "Fluoxetine in pregnancy: slight risk of heart defects in unborn child" (PDF). MHRA. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 10 September 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Rowe T (June 2015). "Drugs in Pregnancy". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 37 (6): 489–92. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30222-X. PMID 26334601.

- Kendall-Tackett K, Hale TW (May 2010). "The use of antidepressants in pregnant and breastfeeding women: a review of recent studies". Journal of Human Lactation. 26 (2): 187–95. doi:10.1177/0890334409342071. PMID 19652194. S2CID 29112093.

- Taylor D, Paton C, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- Bland RD, Clarke TL, Harden LB (February 1976). "Rapid infusion of sodium bicarbonate and albumin into high-risk premature infants soon after birth: a controlled, prospective trial". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 124 (3): 263–7. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90154-x. PMID 2013.

- Koda-Kimble MA, Alldredge BK (2012). Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs (10th ed.). Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-60913-713-7.

- Clark MS, Jansen K, Bresnahan M (November 2013). "Clinical inquiry: How do antidepressants affect sexual function?". The Journal of Family Practice. 62 (11): 660–1. PMID 24288712.

- PRAC recommendations on signals: Adopted at the 13-16 May 2019 PRAC meeting (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 11 June 2019. p. 5. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- "SSRIs, SNRIs: risk of persistent sexual dysfunction". Reactions Weekly. 1838 (5). Springer: 5. 16 January 2021. doi:10.1007/s40278-021-89324-7. S2CID 231669986.

- Bhat V, Kennedy SH (June 2017). "Recognition and management of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 42 (4): E7 – E8. doi:10.1503/jpn.170022. PMC 5487275. PMID 28639936.

- Warner CH, Bobo W, Warner C, Reid S, Rachal J (August 2006). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". American Family Physician. 74 (3): 449–56. PMID 16913164.

- Gabriel M, Sharma V (May 2017). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". CMAJ. 189 (21): E747. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160991. PMC 5449237. PMID 28554948.

- Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisashvili L, Vonderporten EH, Roerecke M, Rehm J, et al. (April 2013). "Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (4): 436–43. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.684. PMID 23446732.

- Lattimore KA, Donn SM, Kaciroti N, Kemper AR, Neal CR, Vazquez DM (September 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and effects on the fetus and newborn: a meta-analysis". Journal of Perinatology. 25 (9): 595–604. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211352. PMID 16015372. S2CID 5558834.

- Gao SY, Wu QJ, Zhang TN, Shen ZQ, Liu CX, Xu X, et al. (October 2017). "Fluoxetine and congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 83 (10): 2134–2147. doi:10.1111/bcp.13321. PMC 5595931. PMID 28513059.

- Wolfson A (12 September 2019). "Prozac maker paid millions to secure favorable verdict in mass shooting lawsuit, victims say". USA Today. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Prozac Litigation - Link to Suicide, Birth Defects & Class Action". Drugwatch.com. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Eli Lilly in storm over Prozac evidence". Financial Times. 30 December 2004. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "They said it was safe". The Guardian. 30 October 1999. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- Eli Lilly. "Internal Document Reporting on Federal Health Agency (BGA) medical comment on Fluoxetine, 25 May 1984" (PDF).

- Leslie LK, Newman TB, Chesney PJ, Perrin JM (July 2005). "The Food and Drug Administration's deliberations on antidepressant use in pediatric patients". Pediatrics. 116 (1): 195–204. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0074. PMC 1550709. PMID 15995053.

- Fornaro M, Anastasia A, Valchera A, Carano A, Orsolini L, Vellante F, et al. (3 May 2019). "The FDA "Black Box" Warning on Antidepressant Suicide Risk in Young Adults: More Harm Than Benefits?". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 10: 294. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00294. PMC 6510161. PMID 31130881.

- Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- Stone MB, Jones ML (17 November 2006). "Clinical Review: Relationship Between Antidepressant Drugs and Suicidality in Adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). pp. 11–74. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- Levenson M, Holland C (17 November 2006). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). pp. 75–140. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- "Suicidality in Children and Adolescents Being Treated With Antidepressant Medications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 November 2018.

- Vitiello B, Silva SG, Rohde P, Kratochvil CJ, Kennard BD, Reinecke MA, et al. (April 2009). "Suicidal events in the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS)". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 70 (5): 741–747. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04607. PMC 2702701. PMID 19552869.

- Committee on Safety of Medicines Expert Working Group (December 2004). "Report on The Safety of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants" (PDF). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D (February 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review". BMJ. 330 (7488): 385. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. PMC 549105. PMID 15718537.

- Cubeddu LX (2016). "Drug-induced Inhibition and Trafficking Disruption of ion Channels: Pathogenesis of QT Abnormalities and Drug-induced Fatal Arrhythmias". Current Cardiology Reviews. 12 (2): 141–54. doi:10.2174/1573403X12666160301120217. PMC 4861943. PMID 26926294.

- Tisdale JE (May 2016). "Drug-induced QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes: Role of the pharmacist in risk assessment, prevention and management". Canadian Pharmacists Journal. 149 (3): 139–52. doi:10.1177/1715163516641136. PMC 4860751. PMID 27212965.

- Castro VM, Clements CC, Murphy SN, Gainer VS, Fava M, Weilburg JB, et al. (January 2013). "QT interval and antidepressant use: a cross sectional study of electronic health records". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 346: f288. doi:10.1136/bmj.f288. PMC 3558546. PMID 23360890.

- "Fluoxetine". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Gury C, Cousin F (September 1999). "". L'Encéphale. 25 (5): 470–6. PMID 10598311.

- Janicak PG, Marder SR, Pavuluri MN (26 December 2011). Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-7877-7.

A 2-week interval is adequate for all of these drugs, with the exception of fluoxetine. Because of the extended half-life of norfluoxetine, a minimum of 5 weeks should lapse between stopping fluoxetine (20mg/day) and starting an MAOI. With higher daily doses, the interval should be longer.

- Dean L, Kane M (2012). "Codeine Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, Scott SA, Pirmohamed M, Esquivel B (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). PMID 28520350. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Perananthan V, Buckley NA (2021). "Opioids and antidepressants: which combinations to avoid". Australian Prescriber. 44 (2): 41–44. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2021.004. S2CID 233579988.

- Hoffelt C, Gross T (January 2016). "A review of significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with antidepressants and their management". The Mental Health Clinician. 6 (1): 35–41. doi:10.9740/mhc.2016.01.035. PMC 6009245. PMID 29955445.

- "Dextromethorphan and fluoxetine Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Fluoxetine and ibuprofen Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "UpToDate". uptodate.com. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Sager JE, Lutz JD, Foti RS, Davis C, Kunze KL, Isoherranen N (June 2014). "Fluoxetine- and norfluoxetine-mediated complex drug-drug interactions: in vitro to in vivo correlation of effects on CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 95 (6): 653–62. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.50. PMC 4029899. PMID 24569517.

- Ciraulo DA, Shader RI, eds. (2011). Pharmacotherapy of Depression (2nd ed.). New York: Humana Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1-60327-434-0.

- ^ Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL (2005). "An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions" (PDF). Psychosomatics. 46 (5): 464–94. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.464. PMID 16145193. S2CID 21838792. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2019.

- An extensive list of possible interactions is available in Lexi-Comp (September 2008). "Fluoxetine". The Merck Manual Professional. Archived from the original on 3 September 2007.

- Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664.

- ^ "Combining certain opioids and commonly prescribed antidepressants may increase the risk of overdose". www.Popsci.com. 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- Hemeryck A, Belpaire F (2002). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Cytochrome P-450 Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions: An Update". Current Drug Metabolism. 3 (1): 13–37. doi:10.2174/1389200023338017. PMID 11876575.

- Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (May 1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–65. doi:10.1007/BF02244985. PMID 7855217.

- Bonhaus, D W, et al. (April–May 1997). "RS-102221: a novel high affinity and selective, 5-HT2C receptor antagonist". Neuropharmacology. 36 (4–5): 621–629. doi:10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00049-x. PMID 9225287.

- Owens MJ, Knight DL, Nemeroff CB (September 2001). "Second-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine". Biological Psychiatry. 50 (5): 345–50. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01145-3. PMID 11543737. S2CID 11247427.

- Stanton T, Bolden-Watson C, Cusack B, Richelson E (June 1993). "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochemical Pharmacology. 45 (11): 2352–2354. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- Perry KW, Fuller RW (1997). "Fluoxetine increases norepinephrine release in rat hypothalamus as measured by tissue levels of MHPG-SO4 and microdialysis in conscious rats". Journal of Neural Transmission. 104 (8–9): 953–66. doi:10.1007/BF01285563. PMID 9451727. S2CID 2679296.

- Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Carter PA, Shaw J, Chernet E, Phebus L, et al. (April 2002). "Fluoxetine, but not other selective serotonin uptake inhibitors, increases norepinephrine and dopamine extracellular levels in prefrontal cortex". Psychopharmacology. 160 (4): 353–61. doi:10.1007/s00213-001-0986-x. PMID 11919662. S2CID 27296534.

- ^ Koch S, Perry KW, Nelson DL, Conway RG, Threlkeld PG, Bymaster FP (December 2002). "R-fluoxetine increases extracellular DA, NE, as well as 5-HT in rat prefrontal cortex and hypothalamus: an in vivo microdialysis and receptor binding study". Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (6): 949–59. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00377-9. PMID 12464452.

- ^ Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A (February 2009). "SSRIs act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) at low doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 9 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.006. PMC 2670606. PMID 19157982.

- Miguelez C, Fernandez-Aedo I, Torrecilla M, Grandoso L, Ugedo L (2009). "alpha(2)-Adrenoceptors mediate the acute inhibitory effect of fluoxetine on locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons". Neuropharmacology. 56 (6–7): 1068–73. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.03.004. PMID 19298831. S2CID 7485264.

- Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H, Laakso A, Kuoppamäki M, Syvälahti E, et al. (August 1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology. 126 (3): 234–40. doi:10.1007/BF02246453. PMID 8876023. S2CID 24889381.

- Brunton PJ (June 2016). "Neuroactive steroids and stress axis regulation: Pregnancy and beyond". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 160: 160–8. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.08.003. PMID 26259885. S2CID 43499796.

- ^ Robinson RT, Drafts BC, Fisher JL (March 2003). "Fluoxetine increases GABA(A) receptor activity through a novel modulatory site". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 304 (3): 978–84. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.044834. PMID 12604672. S2CID 16061756.

- Narita N, Hashimoto K, Tomitaka S, Minabe Y (June 1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with subtypes of sigma receptors in rat brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 307 (1): 117–9. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(96)00254-3. PMID 8831113.

- Hashimoto K (September 2009). "Sigma-1 receptors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical implications of their relationship". Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (3): 197–204. doi:10.2174/1871524910909030197. PMID 20021354.

- "Fluoxetine". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- "Calcium activated chloride channel". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Gulbins E, Palmada M, Reichel M, Lüth A, Böhmer C, Amato D, et al. (July 2013). "Acid sphingomyelinase-ceramide system mediates effects of antidepressant drugs" (PDF). Nature Medicine. 19 (7): 934–8. doi:10.1038/nm.3214. PMID 23770692. S2CID 205391407.

- Brunkhorst R, Friedlaender F, Ferreirós N, Schwalm S, Koch A, Grammatikos G, et al. (October 2015). "Alterations of the Ceramide Metabolism in the Peri-Infarct Cortex Are Independent of the Sphingomyelinase Pathway and Not Influenced by the Acid Sphingomyelinase Inhibitor Fluoxetine". Neural Plasticity. 2015: 503079. doi:10.1155/2015/503079. PMC 4641186. PMID 26605090.

- ^ "Fluoxetine". www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2015). Top 100 drugs: clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- Carhart-Harris RL, Nutt DJ (September 2017). "Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 31 (9): 1091–1120. doi:10.1177/0269881117725915. PMC 5606297. PMID 28858536.

- Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ (May 2017). "How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 4 (5): 409–418. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30015-9. PMC 5410405. PMID 28153641.

- Benfield P, Heel RC, Lewis SP (December 1986). "Fluoxetine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in depressive illness". Drugs. 32 (6): 481–508. doi:10.2165/00003495-198632060-00002. PMID 2878798.

- Kroeze Y, Peeters D, Boulle F, Van Den Hove DL, Van Bokhoven H, Zhou H, et al. (2015). "Long-term consequences of chronic fluoxetine exposure on the expression of myelination-related genes in the rat hippocampus". Translational Psychiatry. 5 (9): e642. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.145. PMC 5068807. PMID 26393488.

- ^ "Prozac Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, Studies, Metabolism". RxList.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- Mandrioli R, Forti GC, Raggi MA (February 2006). "Fluoxetine metabolism and pharmacological interactions: the role of cytochrome p450". Current Drug Metabolism. 7 (2): 127–33. doi:10.2174/138920006775541561. PMID 16472103.

- Hiemke C, Härtter S (January 2000). "Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 85 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(99)00048-0. PMID 10674711.

- ^ Burke WJ, Hendricks SE, McArthur-Miller D, Jacques D, Bessette D, McKillup T, et al. (August 2000). "Weekly dosing of fluoxetine for the continuation phase of treatment of major depression: results of a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 20 (4): 423–7. doi:10.1097/00004714-200008000-00006. PMID 10917403.

- "Drug Treatments in Psychiatry: Antidepressants". Newcastle University School of Neurology, Neurobiology and Psychiatry. 2005. Archived from the original on 17 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ Pérez V, Puiigdemont D, Gilaberte I, Alvarez E, Artigas F, et al. (Grup de Recerca en Trastorns Afectius) (February 2001). "Augmentation of fluoxetine's antidepressant action by pindolol: analysis of clinical, pharmacokinetic, and methodologic factors". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 21 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1097/00004714-200102000-00008. hdl:10261/34714. PMID 11199945. S2CID 13542714.

- Brunswick DJ, Amsterdam JD, Fawcett J, Quitkin FM, Reimherr FW, Rosenbaum JF, et al. (April 2002). "Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine plasma concentrations during relapse-prevention treatment". Journal of Affective Disorders. 68 (2–3): 243–9. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00333-5. PMID 12063152.

- ^ Henry ME, Schmidt ME, Hennen J, Villafuerte RA, Butman ML, Tran P, et al. (August 2005). "A comparison of brain and serum pharmacokinetics of R-fluoxetine and racemic fluoxetine: A 19-F MRS study". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (8): 1576–83. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300749. PMID 15886723.

- Papakostas GI, Perlis RH, Scalia MJ, Petersen TJ, Fava M (February 2006). "A meta-analysis of early sustained response rates between antidepressants and placebo for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 26 (1): 56–60. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000195042.62724.76. PMID 16415707. S2CID 42816815.

- Lemberger L, Bergstrom RF, Wolen RL, Farid NA, Enas GG, Aronoff GR (March 1985). "Fluoxetine: clinical pharmacology and physiologic disposition". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 46 (3 Pt 2): 14–9. PMID 3871765.

- Pato MT, Murphy DL, DeVane CL (June 1991). "Sustained plasma concentrations of fluoxetine and/or norfluoxetine four and eight weeks after fluoxetine discontinuation". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 11 (3): 224–5. doi:10.1097/00004714-199106000-00024. PMID 1741813.

- Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 645–48.

- ^ "Ray W. Fuller, David T. Wong, and Bryan B. Molloy". Science History Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- Wong DT, Bymaster FP, Engleman EA (1995). "Prozac (fluoxetine, Lilly 110140), the first selective serotonin uptake inhibitor and an antidepressant drug: twenty years since its first publication". Life Sciences. 57 (5): 411–41. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(95)00209-O. PMID 7623609.

- "Chemical & Engineering News: Top Pharmaceuticals: Prozac". pubsapp.acs.org. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Wong DT, Horng JS, Bymaster FP, Hauser KL, Molloy BB (August 1974). "A selective inhibitor of serotonin uptake: Lilly 110140, 3-(p-trifluoromethylphenoxy)-N-methyl-3-phenylpropylamine". Life Sciences. 15 (3): 471–9. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(74)90345-2. PMID 4549929.

- Wong DT, Perry KW, Bymaster FP (September 2005). "Case history: the discovery of fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac)". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 4 (9): 764–774. doi:10.1038/nrd1821. PMID 16121130.

- ^ Breggin PR, Breggin GR (1995). Talking Back to Prozac. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-312-95606-6.

- Swiatek J (2 August 2001). "Prozac's profitable run coming to an end for Lilly". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007.

- "Electronic Orange Book". Food and Drug Administration. April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- Simons J (28 June 2004). "Lilly Goes Off Prozac The drugmaker bounced back from the loss of its blockbuster, but the recovery had costs". Fortune Magazine.

- ^ Class S (2 December 2002). "Pharma Overview". Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- "Lilly Menstrual drug OK'd – Jul. 6, 2000". Money.cnn.com. 6 July 2000. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Mechatie E (1 December 1999). "FDA Panel Agrees Fluoxetine Effective For PMDD". International Medical News Group.

- Herper H (25 September 2002). "A Biotech Phoenix Could Be Rising". Forbes.

- Petersen M (2 August 2001). "Drug Maker Is Set to Ship Generic Prozac". The New York Times.

- "Patent Expiration Dates for Common Brand-Name Drugs". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ Spartos C (5 December 2000). "Sarafem Nation". Village Voice. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Galen to Pay $295 Million For U.S. Rights to Lilly Drug". Dow Jones Newswires in The Wall Street Journal. 9 December 2002.

- Murray-West R (10 December 2002). "Galen takes Lilly's reinvented Prozac". Telegraph.

- Petersen M (29 May 2002). "New Medicines Seldom Contain Anything New, Study Finds". The New York Times.

- Vedantam S (29 April 2001). "Renamed Prozac Fuels Women's Health Debate". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Top 200 Generic Drugs by Units in 2010" (PDF). Drug Topics: Voice of the Pharmacist. June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2012.

- Macnair P (September 2012). "BBC – Health: Prozac". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012.

In 2011 over 43 million prescriptions for antidepressants were handed out in the UK and about 14 percent (or nearly 6 million prescriptions) of these were for a drug called fluoxetine, better known as Prozac.

- Jack RH, Hollis C, Coupland C, Morriss R, Knaggs RD, Butler D, et al. (July 2020). Hellner C (ed.). "Incidence and prevalence of primary care antidepressant prescribing in children and young people in England, 1998-2017: A population-based cohort study". PLOS Medicine. 17 (7): e1003215. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003215. PMC 7375537. PMID 32697803.

- Hughes SR, Kay P, Brown LE (January 2013). "Global synthesis and critical evaluation of pharmaceutical data sets collected from river systems". Environmental Science & Technology. 47 (2): 661–77. Bibcode:2013EnST...47..661H. doi:10.1021/es3030148. PMC 3636779. PMID 23227929.

- Stewart AM, Grossman L, Nguyen M, Maximino C, Rosemberg DB, Echevarria DJ, et al. (November 2014). "Aquatic toxicology of fluoxetine: understanding the knowns and the unknowns". Aquatic Toxicology. 156: 269–73. Bibcode:2014AqTox.156..269S. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.08.014. PMID 25245382.

- ^ Sumpter JP, Donnachie RL, Johnson AC (June 2014). "The apparently very variable potency of the anti-depressant fluoxetine". Aquatic Toxicology. 151: 57–60. Bibcode:2014AqTox.151...57S. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.12.010. PMID 24411166.

- ^ Brooks BW, Foran CM, Richards SM, Weston J, Turner PK, Stanley JK, et al. (May 2003). "Aquatic ecotoxicology of fluoxetine". Toxicology Letters. Hot Spot Pollutants: Pharmaceuticals in the Environment. 142 (3): 169–83. doi:10.1016/S0378-4274(03)00066-3. PMID 12691711.

- Mennigen JA, Stroud P, Zamora JM, Moon TW, Trudeau VL (1 July 2011). "Pharmaceuticals as neuroendocrine disruptors: lessons learned from fish on Prozac". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews. 14 (5–7): 387–412. Bibcode:2011JTEHB..14..387M. doi:10.1080/10937404.2011.578559. PMID 21790318. S2CID 43341257.

- Daughton CG, Jones-Lepp TL, eds. (2001). Pharmaceuticals and Care Products in the Environment: Scientific and Regulatory Issues. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 791. Washington, DC, US: American Chemical Society (ACS). pp. xvi+396. doi:10.1021/bk-2001-0791. ISBN 978-0-8412-3739-1. ISSN 0097-6156.

- Martin JM, Saaristo M, Bertram MG, Lewis PJ, Coggan TL, Clarke BO, et al. (March 2017). "The psychoactive pollutant fluoxetine compromises antipredator behaviour in fish". Environmental Pollution. 222: 592–599. Bibcode:2017EPoll.222..592M. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.010. PMID 28063712.

- Barry MJ (21 April 2014). "Fluoxetine inhibits predator avoidance behavior in tadpoles". Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry. 96 (4): 641–49. Bibcode:2014TxEC...96..641B. doi:10.1080/02772248.2014.966713. S2CID 85340761.

- Painter MM, Buerkley MA, Julius ML, Vajda AM, Norris DO, Barber LB, et al. (December 2009). "Antidepressants at environmentally relevant concentrations affect predator avoidance behavior of larval fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas)" (PDF). Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 28 (12): 2677–84. Bibcode:2009EnvTC..28.2677F. doi:10.1897/08-556.1. PMID 19405782. S2CID 25189716. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- Mennigen JA, Lado WE, Zamora JM, Duarte-Guterman P, Langlois VS, Metcalfe CD, et al. (November 2010). "Waterborne fluoxetine disrupts the reproductive axis in sexually mature male goldfish, Carassius auratus". Aquatic Toxicology. 100 (4): 354–64. Bibcode:2010AqTox.100..354M. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.08.016. PMID 20864192.

- Schultz MM, Painter MM, Bartell SE, Logue A, Furlong ET, Werner SL, et al. (July 2011). "Selective uptake and biological consequences of environmentally relevant antidepressant pharmaceutical exposures on male fathead minnows". Aquatic Toxicology. 104 (1–2): 38–47. Bibcode:2011AqTox.104...38S. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.03.011. PMID 21536011.

- Mennigen JA, Sassine J, Trudeau VL, Moon TW (October 2010). "Waterborne fluoxetine disrupts feeding and energy metabolism in the goldfish Carassius auratus". Aquatic Toxicology. 100 (1): 128–37. Bibcode:2010AqTox.100..128M. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.07.022. PMID 20692053.

- Gaworecki KM, Klaine SJ (July 2008). "Behavioral and biochemical responses of hybrid striped bass during and after fluoxetine exposure". Aquatic Toxicology. 88 (4): 207–13. Bibcode:2008AqTox..88..207G. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.04.011. PMID 18547660.

- ^

- Richmond EK, Rosi EJ, Reisinger AJ, Hanrahan BR, Thompson RM, Grace MR (1 January 2019). "Influences of the antidepressant fluoxetine on stream ecosystem function and aquatic insect emergence at environmentally realistic concentrations". Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 34 (1): 513–531. Bibcode:2019JFEco..34..513R. doi:10.1080/02705060.2019.1629546. ISSN 0270-5060. S2CID 196679455.

- Bundschuh M, Pietz S, Roodt AP, Kraus JM (April 2022). "Contaminant fluxes across ecosystems mediated by aquatic insects". Current Opinion in Insect Science. 50: 100885. Bibcode:2022COIS...5000885B. doi:10.1016/j.cois.2022.100885. PMID 35144033. S2CID 246673478.

- ^

- Qin Q, Chen X, Zhuang J (9 September 2014). "The Fate and Impact of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Agricultural Soils Irrigated With Reclaimed Water". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (13): 1379–1408. doi:10.1080/10643389.2014.955628. ISSN 1064-3389. S2CID 94839032.

- Carvalho PN, Basto MC, Almeida CM, Brix H (October 2014). "A review of plant-pharmaceutical interactions: from uptake and effects in crop plants to phytoremediation in constructed wetlands". Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 21 (20). Springer: 11729–11763. Bibcode:2014ESPR...2111729C. doi:10.1007/s11356-014-2550-3. PMID 24481515. S2CID 25786586.

- Christou A, Papadavid G, Dalias P, Fotopoulos V, Michael C, Bayona JM, et al. (March 2019). "Ranking of crop plants according to their potential to uptake and accumulate contaminants of emerging concern". Environmental Research. 170. Elsevier: 422–432. Bibcode:2019ER....170..422C. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.048. hdl:10261/202657. PMID 30623890. S2CID 58564142.

- Wu C, Spongberg AL, Witter JD, Fang M, Czajkowski KP (August 2010). "Uptake of pharmaceutical and personal care products by soybean plants from soils applied with biosolids and irrigated with contaminated water". Environmental Science & Technology. 44 (16). American Chemical Society (ACS): 6157–6161. Bibcode:2010EnST...44.6157W. doi:10.1021/es1011115. PMID 20704212. S2CID 20021866.

- ^ Solsona SP, Montemurro N, Chiron S, Barceló D, eds. (2021). Interaction and Fate of Pharmaceuticals in Soil-Crop Systems. Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Vol. 103. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. x+530. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-61290-0. ISBN 978-3-030-61289-4. ISSN 1867-979X. S2CID 231746862.

- MacPherson M (2 September 1990). "Prozac, Prejudice and the Politics of Depression". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Duquette A, Dorr L (2 April 2010). "FAA Proposes New Policy on Antidepressants for Pilots" (Press release). Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- Office of Aerospace Medicine, Federal Aviation Administration (2 December 2016). "Decision Considerations – Aerospace Medical Dispositions: Item 47. Psychiatric Conditions – Use of Antidepressant Medications". Guide for Aviation Medical Examiners. Washington, DC: United States Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017.

- "Mental Health GM - Centrally Acting Medication". Civil Aviation Authority. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- "Class 1/2 Certification – Depression" (PDF). Civil Aviation Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^

- • McCammon JM, Sive H (2015). "Addressing the Genetics of Human Mental Health Disorders in Model Organisms". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 16 (1). Annual Reviews: 173–197. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-050048. PMID 26002061. S2CID 19597664.

- • Ziv L, Muto A, Schoonheim PJ, Meijsing SH, Strasser D, Ingraham HA, et al. (June 2013). "An affective disorder in zebrafish with mutation of the glucocorticoid receptor". Molecular Psychiatry. 18 (6): 681–691. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.64. PMC 4065652. PMID 22641177. S2CID 11962425. NIHMSID: NIHMS368312.

- ^

- • Mangoni AA, Tuccinardi T, Collina S, Vanden Eynde JJ, Muñoz-Torrero D, Karaman R, et al. (June 2018). "Breakthroughs in Medicinal Chemistry: New Targets and Mechanisms, New Drugs, New Hopes-3". Molecules. 23 (7): 1596. doi:10.3390/molecules23071596. PMC 6099979. PMID 29966350. S2CID 49644934.

- • Weeks JC, Roberts WM, Leasure C, Suzuki BM, Robinson KJ, Currey H, et al. (January 2018). "Sertraline, Paroxetine, and Chlorpromazine Are Rapidly Acting Anthelmintic Drugs Capable of Clinical Repurposing". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 975. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8..975W. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-18457-w. PMC 5772060. PMID 29343694. S2CID 205636792.