This is an old revision of this page, as edited by David Hedlund (talk | contribs) at 01:01, 18 February 2013 (Moved to "Alcohol and health"). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:01, 18 February 2013 by David Hedlund (talk | contribs) (Moved to "Alcohol and health")(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)|

Alcoholic beverage is currently a Drugs good article nominee. Nominated by David Hedlund at 2013-02-05 Any editor who has not nominated or contributed significantly to this article may review it according to the good article criteria to decide whether or not to list it as a good article. To start the review process, click start review and save the page. (See here for the good article instructions.)

|

An alcoholic beverage is a drink containing ethyl alcohol (ethanol) and often small quantities of other consumable alcohols. Alcoholic beverages are divided into three general classes for taxation and regulation of production: beers, wines, and spirits (or distilled beverage). They are legally consumed in most countries, and over 100 countries have laws regulating their production, sale, and consumption. In particular, such laws specify the minimum age at which a person may legally buy or drink them. This minimum age varies between 16 and 25 years, depending upon the country and the type of drink. Most nations set the age at 18 years.

The production and consumption of alcohol occurs in most cultures of the world, from hunter-gatherer peoples to nation-states. Alcoholic beverages are often an important part of social events in these cultures.

Alcoholic beverages

Distilled beverage

See also: Distilled beverage

A distilled beverage, spirit, or liquor is an alcoholic beverage produced by distilling (i.e., concentrating by distillation) ethanol produced by means of fermenting grain, fruit, or vegetables. The term hard liquor is used in North America to distinguish distilled beverages from undistilled ones (implicitly weaker).

Freeze distillation concentrates methanol and fusel alcohols (fermentation by-products partially removed by distillation) in applejack to unhealthy levels. As a result, many countries prohibit such applejack as a health measure. However, reducing methanol with the absorption of 4A molecular sieve is a practical method for production.

Vodka, gin, baijiu, tequila, whisky, brandy, and soju are examples of distilled beverages. Undistilled fermented beverages include beer, wine, and cider.

Rectified spirit

See also: Rectified spirit

A rectified spirit, rectified alcohol, or neutral spirit is highly concentrated ethanol which has been purified by means of repeated distillation, a process that is called rectification. It typically contains 95% alcohol by volume (ABV). Rectified spirits are used in mixed drinks, in the production of liqueurs, for medicinal purposes, and as a household solvent. In chemistry, a tincture is a solution that has alcohol as its solvent.

Neutral grain spirit

See also: Neutral grain spiritNeutral grain spirit (also called pure grain alcohol (PGA) or grain neutral spirit (GNS)) is a clear, colorless, flammable liquid that has been distilled from a grain-based mash to a very high level of ethanol content. The term neutral refers to the spirit's lacking the flavor that would have been present if the mash ingredients were distilled to a lower level of alcoholic purity, and also lacking any flavoring added to it after distillation (as is done, for example, with gin). Other kinds of spirits, such as whisky, are distilled to a lower alcohol percentage in order to preserve the flavor of the mash.

Fermented beverages

See also: List of alcoholic beverages

Beer and wine are produced by fermentation of sugar- or starch-containing plant material. Beverages produced by fermentation followed by distillation have a higher alcohol content and are known as liquor or spirits.

Chemical composition

Alcohols

Main article: AlcoholAlcohol is a general term for any organic compound in which a hydroxyl group (-O H) is bound to a carbon atom, which in turn may be bound to other carbon atoms and further hydrogens. Alcohols other than ethanol are found in trace quantities in alcoholic beverages. Ethanol is the active ingredient in alcoholic beverages and is produced by fermentation.

Congeners

See also: congener (alcohol) and hangoverCongeners are biologically active chemicals (chemicals which exert an effect on the body or brain) found in fermenation ethanol in trace quantities. Bourbon has a higher congener concentration than vodka. It has been suggested that some of these substances contribute to the symptoms of a hangover. Congeners include:

Furfural

Furfural is a congener that inhibits yeast metabolism. It may be added to alcoholic beverages during the fermentation stage. Although it occurs in many foods and flavorants, furfural is toxic with an LD50 of 65 mg/kg (oral, rat).

Tannins

Tannins are congeners found in wine. Tannins contain powerful antioxidants such as polyphenols.

Fusel alcohol

Main article: Fusel alcoholFusel alcohols, also sometimes called fusel oils, or potato oil in Europe, are a mixture of several alcohols (chiefly 2-methyl-1-butanol) produced as a by-product of ethanol fermentation.

The term fusel is German for "bad liquor".

Fusel alcohols may contain up to 50 different components, where the chief constituents are isobutanol (2-methyl-1-propanol), propanol, and above all, the pair of isoamylalkohols: 2-methyl-1-butanol and 3-methyl-1-butanol. Occurrence of flavor compounds and some other compounds in alcoholic beverages for beer, wine, and spirits, are listed in hundreds in a document. Methanol is a toxic alcohol also found in trace quantities.

Excessive concentrations of these fractions may cause off-flavors, sometimes described as "spicy", "hot", or "solvent-like". Some beverages, such as rum, whisky (especially Bourbon), incompletely rectified vodka (eg Siwucha), and traditional ales and ciders, are expected to have relatively high concentrations of fusel alcohols as part of their flavor profile. In other beverages, such as Korn, vodka, and lagers, the presence of fusel alcohols is considered a fault.

Beverages by fermentation ingredients

The names of some alcoholic beverages are determined by their base material. In general, a beverage fermented from a grain mash will be called a beer. If the fermented mash is distilled, then the beverage is a spirit.

Wine and brandy are usually made from grapes but when they are made from another kind of fruit, they are distinguished as fruit wine or fruit brandy. The kind of fruit must be specified, such as "cherry brandy" or "plum wine."

Beer is made from barley or a blend of several grains.

Whiskey (or whisky) is made from grain or a blend of several grains. The type of whiskey (scotch, rye, bourbon, or corn) is determined by the primary grain.

Vodka is distilled from fermented grain. It is highly distilled so that it will contain less of the flavor of its base material. Gin is a similar distillate but it is flavored by juniper berries and sometimes by other herbs as well.

In the United States and Canada, cider often means unfermented apple juice (sometimes called sweet cider), and fermented apple juice is called hard cider. In the United Kingdom and Australia, cider refers to the alcoholic beverage.

Applejack is sometimes made by means of freeze distillation.

Grains

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| barley | beer, ale, barley wine | Scotch whisky, Irish whiskey, shōchū (mugijōchū) (Japan) |

| rye | rye beer, kvass | rye whiskey, vodka (Poland), Korn (Germany) |

| corn | chicha, corn beer, tesguino | Bourbon whiskey; and vodka (rarely) |

| sorghum | burukutu (Nigeria), pito (Ghana), merisa (southern Sudan), bilibili (Chad, Central African Republic, Cameroon) | maotai, gaoliang, certain other types of baijiu (China). |

| wheat | wheat beer | horilka (Ukraine), vodka, wheat whisky, weizenkorn (Germany) |

| rice | beer, brem (Bali), huangjiu and choujiu (China), Ruou gao (Vietnam), sake (Japan), sonti (India), makgeolli (Korea), tuak (Borneo Island), thwon (Nepal) | aila (Nepal), rice baijiu (China), shōchū (komejōchū) and awamori (Japan), soju (Korea) |

| millet | millet beer (Sub-Saharan Africa), tongba (Nepal, Tibet), boza (the Balkans, Turkey) | |

| buckwheat | shōchū (sobajōchū) (Japan) |

Fruit juice

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| juice of grapes, | wine | brandy, Cognac (France), Vermouth, Armagnac (France), Branntwein (Germany), pisco (Peru, Chile), (Grozdova) Rakia (The Balkans, Turkey), singani (Bolivia), Arak (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan), törkölypálinka (Hungary) |

| juice of apples | cider (U.S.: "hard cider"), Apfelwein | applejack (or apple brandy), calvados, cider |

| juice of pears | perry, or pear cider; poiré (France) | Poire Williams, pear brandy, Eau-de-vie (France), pálinka (Hungary), Krushova rakia / Krushevitsa (Bulgaria) |

| juice of plums | plum wine | slivovitz, țuică, umeshu, pálinka, Slivova rakia / Slivovitsa (Bulgaria) |

| juice of apricots | Kaisieva rakia (Bulgaria) | |

| juice of pineapples | tepache (Mexico) | |

| junipers | borovička (Slovakia) | |

| bananas or plantains | Chuoi hot (Vietnam), urgwagwa (Uganda, Rwanda), mbege (with millet malt; Tanzania), kasikisi (with sorghum malt; Democratic Republic of the Congo) | |

| gouqi | gouqi jiu (China) | gouqi jiu (China) |

| coconut | Toddy (Sri Lanka, India) | arrack, lambanog (Sri Lanka, India, Philippines) |

| ginger with sugar, ginger with raisins | ginger ale, ginger beer, ginger wine | |

| Myrica rubra | yangmei jiu (China) | yangmei jiu (China) |

| pomace | pomace wine | Raki/Ouzo/Pastis/Sambuca (Turkey/Greece/France/Italy), tsipouro/tsikoudia (Greece), grappa (Italy), Trester (Germany), marc (France), orujo (Spain), zivania (Cyprus), aguardente (Portugal), tescovină (Romania), Arak (Iraq) |

Vegetables

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| juice of ginger root | ginger beer (Botswana) | |

| potato | potato beer | horilka (Ukraine), vodka (Poland and Germany), akvavit (Scandinavia), poitín (poteen) (Ireland) |

| sweet potato | shōchū (imojōchū) (Japan), soju (Korea) | |

| cassava/manioc/yuca | nihamanchi (South America), kasiri (Sub-Saharan Africa), chicha (Ecuador) | |

| juice of sugarcane, or molasses | basi, betsa-betsa (regional) | rum (Caribbean), pinga or cachaça (Brasil), aguardiente, guaro |

| juice of agave | pulque | tequila, mezcal, raicilla |

Other ingredients

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| sap of palm | coyol wine (Central America), tembo (Sub-Saharan Africa), toddy (Indian subcontinent) | |

| sap of Arenga pinnata, Coconut, Borassus flabellifer | Tuak (Indonesia) | Arrack |

| honey | mead, horilka (Ukraine), tej (Ethiopia) | distilled mead (mead brandy or honey brandy) |

| milk | kumis, kefir, blaand | arkhi (Mongolia) |

| sugar | kilju and mead or sima (Finland) | shōchū (kokutō shōchū): made from brown sugar (Japan) |

Flavoring

Alcohol is a moderately good solvent for many fatty substances and essential oils. This attribute facilitates the use of flavoring and coloring compounds in alcoholic beverages, especially distilled beverages. Flavors may be naturally present in the beverage’s base material. Beer and wine may be flavored before fermentation. Spirits may be flavored before, during, or after distillation.

Sometimes flavor is obtained by allowing the beverage to stand for months or years in oak barrels, usually American or French oak.

A few brands of spirits have fruit or herbs inserted into the bottle at the time of bottling.

Tax regulated classes

Beer

Main article: BeerBeer is one of the world's oldest and most widely consumed alcoholic beverages, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches which are mainly derived from cereal grains — most commonly malted barley although wheat, maize (corn), and rice are also used.

Alcoholic beverages that are distilled after fermentation, or are fermented from non-cereal sources (such as grapes or honey), or are fermented from unmalted cereal grain are not classified as beer.

The two main types of beer are lager and ale. Ale is further classified into varieties such as pale ale, stout, and brown ale, whereas different types of lager include black lager, pilsener, and bock.

Most beer is flavored with hops, which add bitterness and act as a natural preservative. Other flavorings, such as fruits or herbs, may also be used.

The alcoholic strength of beer is usually 4–6% alcohol by volume (ABV), but it may be less than 2% or greater than 25%. Beers having an ABV of 60% (120 proof) have been produced by freezing brewed beer and removing water in the form of ice, a process referred to as "ice distilling".

Beer is part of the drinking culture of various nations and has acquired social traditions such as beer festivals, pub games, and pub crawling (sometimes known as bar hopping).

The basics of brewing beer are shared across national and cultural boundaries. The beer-brewing industry is global in scope, consisting of several dominant multinational companies and thousands of smaller producers, which range from regional breweries to microbreweries.

Wine

Main article: WineWine is produced from grapes, and from fruits such as plums, cherries, or apples. Wine involves a longer fermentation process than beer and also a long aging process (months or years), resulting in an alcohol content of 9–16% ABV. Sparkling wine can be made by means of a secondary fermentation.

Fortified wine is wine (such as port or sherry), to which a distilled beverage (usually brandy) has been added.

Spirits

Main article: Distilled beverageUnsweetened, distilled, alcoholic beverages that have an alcohol content of at least 20% ABV are called spirits. Spirits are produced by the distillation of a fermented base product. Distilling concentrates the alcohol and eliminates some of the congeners. For the most common distilled beverages, such as whiskey and vodka, the alcohol content is around 40%.

Spirits can be added to wines to create fortified wines, such as port and sherry.

Distilled alcoholic beverages were first recorded in Europe in the mid-12th century. By the early 14th century, they had spread throughout the European continent. They also spread eastward from Europe, mainly due to the Mongols, and began to be seen in China no later than the 14th century.

Paracelsus gave alcohol its modern name, which is derived from an Arabic word that means “finely divided” (a reference to distillation).

Fortified beverages

Fortified wine

See also: Fortified wine

Fortified wine is wine with an added distilled beverage (usually brandy). Fortified wine is distinguished from spirits made from wine in that spirits are produced by means of distillation, while fortified wine is simply wine that has had a spirit added to it. Many different styles of fortified wine have been developed, including Port, Sherry, Madeira, Marsala, Commandaria wine and the aromatized wine Vermouth.

Mixed drinks

See also: Mixed drinksMixed drinks include alcoholic mixed drinks (cocktails, beer cocktails, flaming beverages, fortified wines, mixed drink shooters and drink shots, wine cocktails) and non-alcoholic mixed drinks (including punches).

Blending and caffeinated alcoholic drinks may also be called mixed drinks.

Ready to drink

See also: Ready to drinkStandards

Alcohol concentration

Main articles: Alcohol by volume and alcohol proofThe concentration of alcohol in a beverage is usually stated as the percentage of alcohol by volume (ABV) or as proof. In the United States, proof is twice the percentage of alcohol by volume at 60 degrees Fahrenheit (e.g. 80 proof = 40% ABV). Degrees proof were formerly used in the United Kingdom, where 100 degrees proof was equivalent to 57.1% ABV. Historically, this was the most dilute spirit that would sustain the combustion of gunpowder.

Ordinary distillation cannot produce alcohol of more than 95.6% ABV (191.2 proof) because at that point alcohol is an azeotrope with water. A spirit which contains a very high level of alcohol and does not contain any added flavoring is commonly called a neutral spirit. Generally, any distilled alcoholic beverage of 170 proof or higher is considered to be a neutral spirit.

Most yeasts cannot reproduce when the concentration of alcohol is higher than about 18%, so that is the practical limit for the strength of fermented beverages such as wine, beer, and sake. However, some strains of yeast have been developed that can reproduce in solutions of up to 25% ABV.

Alcohol-free definition controversy

The term alcohol-free (eg alcohol-free beer) is often used to describe a product that contains 0% ABV; As such, it is permitted by Islam, and they are also popular in countries that enforce alcohol prohibition, such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iran.

However, alcohol is legal in most countries of the world where alcohol culture also is prevalent. Laws vary in countries when beverages must indicate the strength but also what they define as alcohol-free; Experts calling the label “misleading” and a threat to recovering alcoholics.

In the EU the labeling of beverages containing more than 1.2% by volume of alcohol must indicate the actual alcoholic strength by volume, i.e. showing the word "alcohol" or the abbreviation "alc." followed by the symbol "% vol."

Most of the alcohol-free drinks sold in Sweden’s state-run liquor store monopoly Systembolaget actually contain alcohol, with experts calling the label “misleading” and a threat to recovering alcoholics. Systembolaget define alcohol-free as a drink that contains a maximum of 0.5 percent alcohol by volume. Interestingly, the drug policy of Sweden is based on zero tolerance.

Standard drinks

Main articles: Standard drink § Pure alcohol measure, Alcohol equivalence, and Unit of alcohol

A standard drink is a notional drink that contains a specified amount of pure alcohol. The standard drink is used in many countries to quantify alcohol intake. It is usually expressed as a measure of beer, wine, or spirits. One standard drink always contains the same amount of alcohol regardless of serving size or the type of alcoholic beverage.

The standard drink varies significantly from country to country. For example, it is 7.62 ml (6 grams) of alcohol in Austria, but in Japan it is 25 ml (19.75 grams).

In the United Kingdom, there is a system of units of alcohol which serves as a guideline for alcohol consumption. A single unit of alcohol is defined as 10 ml. The number of units present in a typical drink is printed on bottles. The system is intended as an aid to people who are regulating the amount of alcohol they drink; it is not used to determine serving sizes.

In the United States, the standard drink contains 0.6 US fluid ounces (18 ml) of alcohol. This is approximately the amount of alcohol in a 12-US-fluid-ounce (350 ml) glass of beer, a 5-US-fluid-ounce (150 ml) glass of wine, or a 1.5-US-fluid-ounce (44 ml) glass of a 40% ABV (80 proof) spirit.

Serving sizes

See also: Shot glass § SizesIn the United Kingdom, serving size in licensed premises is regulated under the Weights and Measures Act (1985). Spirits (gin, whisky, rum, and vodka) are sold in 25 ml or 35 ml quantities or multiples thereof. Beer is typically served in pints (568 ml), but is also served in half-pints or third-pints.

In Ireland, the serving size of spirits is 35.5 ml or 71 ml. Beer is usually served in pints or half-pints ("glasses"). In the Netherlands and Belgium, standard servings are 250 and 500 ml for pilsner; 300 and 330 ml for ales.

The shape of a glass can have a significant effect on how much one pours. A Cornell University study of students and bartenders' pouring showed both groups pour more into short, wide glasses than into tall, slender glasses. Aiming to pour one shot of alcohol (1.5 ounces or 44.3 ml), students on average poured 45.5 ml & 59.6 ml (30% more) respectively into the tall and short glasses. The bartenders scored similarly, on average pouring 20.5% more into the short glasses. More experienced bartenders were more accurate, pouring 10.3% less alcohol than less experienced bartenders. Practice reduced the tendency of both groups to over pour for tall, slender glasses but not for short, wide glasses. These misperceptions are attributed to two perceptual biases: (1) Estimating that tall, slender glasses have more volume than shorter, wider glasses; and (2) Over focusing on the height of the liquid and disregarding the width.

Alcohol consumption

History

Main articles: History of alcoholic beverages and drinking cultureAlcoholic beverages have been drunk by people around the world since ancient times. Reasons that have been proposed for drinking them include:

- They are part of a people's standard diet

- They are drunk for medical reasons

- For their relaxant effects

- For their euphoric effects

- For recreational purposes

- For artistic inspiration

- For their putative aphrodisiac effects

Archaeological record

Chemical analysis of traces absorbed and preserved in pottery jars from the neolithic village of Jiahu in Henan province in northern China has revealed that a mixed fermented beverage made from rice, honey, and fruit was being produced as early as 9,000 years ago. This is approximately the time when barley beer and grape wine were beginning to be made in the Middle East.

Recipes have been found on clay tablets and art in Mesopotamia that show people using straws to drink beer from large vats and pots.

The Hindu ayurvedic texts describe both the beneficial effects of alcoholic beverages and the consequences of intoxication and alcoholic diseases.

The medicinal use of alcohol was mentioned in Sumerian and Egyptian texts dating from about 2100 BC. The Hebrew Bible recommends giving alcoholic drinks to those who are dying or depressed, so that they can forget their misery (Proverbs 31:6-7).

Wine was consumed in Classical Greece at breakfast or at symposia, and in the 1st century BC it was part of the diet of most Roman citizens. Both the Greeks and the Romans generally drank diluted wine (the strength varying from 1 part wine and 1 part water, to 1 part wine and 4 parts water).

In Europe during the Middle Ages, beer, often of very low strength, was an everyday drink for all classes and ages of people. A document from that time mentions nuns having an allowance of six pints of ale each day. Cider and pomace wine were also widely available; grape wine was the prerogative of the higher classes.

By the time the Europeans reached the Americas in the 15th century, several native civilizations had developed alcoholic beverages. According to a post-conquest Aztec document, consumption of the local "wine" (pulque) was generally restricted to religious ceremonies but was freely allowed to those who were older than 70 years.

The natives of South America produced a beer-like beverage from cassava or maize, which had to be chewed before fermentation in order to turn the starch into sugar. (Beverages of this kind are known today as cauim or chicha.) This chewing technique was also used in ancient Japan to make sake from rice and other starchy crops.

Alcohol in American history

In the early 19th century, Americans had inherited a hearty drinking tradition. Many types of alcohol were consumed. One reason for this heavy drinking was attributed to an overabundance of corn on the western frontier, which encouraged the widespread production of cheap whiskey. It was at this time that alcohol became an important part of the American diet. In the 1820s, Americans drank seven gallons of alcohol per person annually.

During the 19th century, Americans drank alcohol in two distinctive ways. One way was to drink small amounts daily and regularly, usually at home or alone. The other way consisted of communal binges. Groups of people would gather in a public place for elections, court sessions, militia musters, holiday celebrations, or neighborly festivities. Participants would typically drink until they became intoxicated.

Routes of administration

Inhalation

Although this method is rare, it is becoming more and more common.

Nebulizer

A nebulizer device that vaporizes liquor (distilled spirits) and mixes it with oxygen into small aerosol droplets so that it can be more easily inhaled into the lungs.

Oral

Drinking is the usual way of administer alcoholic beverages but distilled beverages have been used by other routes as well.

Molecular encapsulation

Main article: Alcohol powderAlcohol powder is molecular encapsulated alcohol. The powder will produce an alcoholic drink when mixed with water. Alcohol powder can simply be made by molecular encapsulation in cyclodextrin, a sugar which can absorb an estimated 60% of its own weight.

Gelatin capsules

Distilled beverages can be placed into gelatin capsules as a liquid or cyclodextrin complexed powder to avoid an unpleasant taste. To date, a company called Alcogel have patented ethanol in softgel. This capsule will directly put 190 proof alcohol into the stomach by swallowing it whole. 12 capsules provides as much alcohol as there is in a 33 cL (12.5 oz) beer. However, in the future, Alcogel plans to work with the medical field to change the way alcohol is currently prescribed and find better ways for alcohol detoxification.

Intravenous

- Recreational

- Distilled ethanol beverages are sometimes used by intravenous drug users, occasionally when they are cut of supply of other drugs and there are to little ethanol to get intoxicated orally. However, another alcohol, ethchlorvynol, is not compatible with intravenous injection and serious injury or death can occur when it is used in this manner

- Medical

- Ethylene glycol poisoning: Doctors saved a poisoned tourist using vodka drip. Pharmaceutical grade ethanol is usually given intravenously as a 5 or 10% solution in 5% dextrose, but it is also sometimes given orally in the form of a strong spirit such as whisky, vodka, or gin.

- Methanol poisoning: A 10% ethanol solution administered intravenously is a safe and effective antidote for severe methanol poisoning.

Applications

In many countries, people drink alcoholic beverages at lunch and dinner. Studies have found that when food is eaten before drinking alcohol, alcohol absorption is reduced and the rate at which alcohol is eliminated from the blood is increased. The mechanism for the faster alcohol elimination appears to be unrelated to the type of food. The likely mechanism is food-induced increases in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes and liver blood flow.

At times and places of poor public sanitation (such as Medieval Europe), the consumption of alcoholic drinks was a way of avoiding water-borne diseases such as cholera. Small beer and faux wine, in particular, were used for this purpose. Although alcohol kills bacteria, its low concentration in these beverages would have had only a limited effect. More important was that the boiling of water (required for the brewing of beer) and the growth of yeast (required for fermentation of beer and wine) would tend to kill dangerous microorganisms. The alcohol content of these beverages allowed them to be stored for months or years in simple wood or clay containers without spoiling. For this reason, they were commonly kept aboard sailing vessels as an important (or even the sole) source of hydration for the crew, especially during the long voyages of the early modern period.

In cold climates, potent alcoholic beverages such as vodka are popularly seen as a way to “warm up” the body, possibly because alcohol is a quickly absorbed source of food energy and because it dilates peripheral blood vessels (peripherovascular dilation). This is a misconception because the “warmth” is actually caused by a transfer of heat from the body’s core to its extremities, where it is quickly lost to the environment. However, the perception alone may be welcomed when only comfort, rather than hypothermia, is a concern.

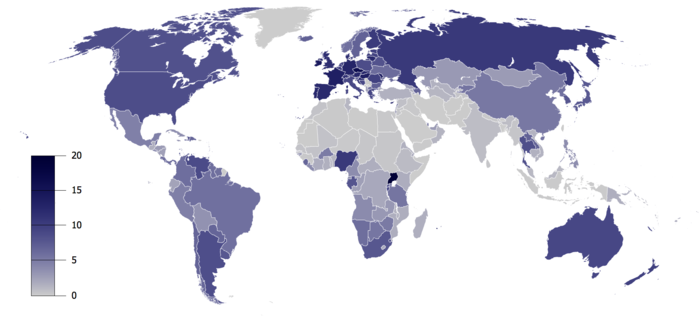

Alcohol consumption by country

Main article: List of countries by alcohol consumption

Accessibility

Alcohol laws

Main article: Alcohol lawsAlcohol laws are laws in relation to the manufacture, use, influence and sale of ethanol (ethyl alcohol, EtOH) or alcoholic beverages that contains ethanol.

Alcohol laws often seek to reduce the availability of alcoholic beverages, often with the stated purpose of reducing the health and social side effect of their consumption. This can take the form of age limits for alcohol consumption, and distribution only in licensed stores or in monopoly stores. Often, this is combined with some form of alcohol taxation.

Alcohol and religion

Main articles: Religion and alcohol, Christianity and alcohol, Islam and alcohol, and Alcohol in the BibleThe current Arabic name for alcohol in The Qur'an, in verse 37:47, uses the word الغول al-ġawl —properly meaning "spirit" or "demon"—with the sense "the thing that gives the wine its headiness." The term ethanol was invented 1838, modeled on German äthyl (Liebig), from Greek aither (see ether) + hyle "stuff.". Ether in late 14c. meant "upper regions of space," from Old French ether and directly from Latin aether "the upper pure, bright air," from Greek aither "upper air; bright, purer air; the sky," from aithein "to burn, shine," from PIE root *aidh- "to burn" (see edifice).

Monastic beer production

Main articles: Trappist beer and abbey beersTrappist beer is brewed by Trappist breweries. Eight monasteries — six in Belgium, one in the Netherlands and one in Austria — currently brew beer and sell it as Authentic Trappist Product.

The designation "abbey beers" (Bières d'Abbaye or Abdijbier) was originally used for any monastic or monastic-style beer. After the introduction of an official Trappist beer designation by the International Trappist Association in 1997, it came to mean products similar in style or presentation to monastic beers.

Some abbeys have a lighter, less alcoholic versions of the beers for the internal consumption (Petite Orval or Chimay Dorée) called patersbier.

Consumption

Some alcoholic beverages have been invested with religious significance, as in the ancient Greco-Roman religion, such as in the ecstatic rituals of Dionysus (also called Bacchus). Some have postulated that pagan religions actively promoted alcohol and drunkenness as a means of fostering fertility. Alcohol was believed to increase sexual desire and to make it easier to approach another person for sex. For example, Norse paganism considered alcohol to be the sap of Yggdrasil. Drunkenness was an important fertility rite in this religion.

Many Christian denominations use wine in the Eucharist or Communion and permit alcohol in moderation. Other denominations use unfermented grape juice in Communion and either abstain from alcohol by choice or prohibit it outright.

Judaism uses wine on Shabbat for Kiddush as well as in the Passover ceremony, Purim, and other religious ceremonies. The drinking of alcohol is allowed. Some Jewish texts, e.g. the Talmud, encourage moderate drinking on holidays (such as Purim) in order to make the occasion more joyous.

Prohibition

Some religions forbid, discourage, or restrict the drinking of alcoholic beverages for various reasons. These include Islam, Jainism, the Bahá'í Faith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Church of Christ, Scientist, the United Pentecostal Church International, Theravada, most Mahayana schools of Buddhism, some Protestant denominations of Christianity, some sects of Taoism (Five Precepts (Taoism) and Ten Precepts (Taoism)), and Hinduism.

The Pali Canon, the scripture of Theravada Buddhism, depicts refraining from alcohol as essential to moral conduct because alcohol causes a loss of mindfulness. The fifth of the Five Precepts states, "Surā-meraya-majja-pamādaṭṭhānā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi." The English translation is, "I undertake to refrain from fermented drink that causes heedlessness." Technically this prohibition does not cover drugs other than alcohol. But its purport is not that alcohol is an evil but that the carelessness it produces creates bad karma. Therefore any substance (beyond tea or mild coffee) that affects one's mindfulness is considered to be covered by this prohibition.

See also

- Alcohol and Drugs History Society

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

- Cooking with alcohol

References

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ "Minimum Age Limits Worldwide". International Center for Alcohol Policies. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ^ Arnold, John P (2005). Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology. Cleveland, Ohio: Reprint Edition by BeerBooks. ISBN 0-9662084-1-2.

- ^ "Volume of World Beer Production". European Beer Guide. Archived from the original on 28 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Distilled spirit/distilled liquor". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- MA Hui-Ling; et al. (2006). "Study on Method of Decreasing Methanol in Apple Pomace Spirit". Food Science. 27 (4): 138–42.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - "Avoid hangover with white spirits". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. 2013-01-10. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- Whisky hangover 'worse than vodka, a study suggests', BBC News. Accessed 2009-12-19

- "ChemIDplus Advanced". Chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- "Definition of fusel oil". Oxforddictionaries.com. 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- Hazelwood, Lucie A.; Daran, Jean-Marc; van Maris, Antonius J. A.; Pronk, Jack T.; Dickinson, J. Richard (2008). "The Ehrlich pathway for fusel alcohol production: a century of research on Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 (8): 2259–66. doi:10.1128/AEM.02625-07. PMC 2293160. PMID 18281432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Chemistry of a Hangover — Alcohol and its Consequences Part 3". ChemistryViews.org. 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- Aroma of Beer, Wine and Distilled Alcoholic Beverages. books.google.com. 1983-05-31. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Nykänen & Suomalainen (1983), monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol44/mono44-12.pdf

- Aroma of Beer, Wine and Distilled Alcoholic Beverages

- "Stone Age Had Booze" Popular Science, May 1932

- Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. books.google.com. ISBN 978-0-415-31121-2. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- Lichine, Alexis. Alexis Lichine’s New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th edition) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 707–709.

- Forbes, Robert James (1970). A short history of the art of distillation: from the beginnings up to the death of Cellier Blumenthal. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-00617-1. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Lichine, Alexis (1987). Alexis Lichine’s New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 236. ISBN 0-394-56262-3.

- Robinson, J., ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- Lichine, Alexis. Alexis Lichine’s New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th edition) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 365.

- ^ "Sweden's alcohol-free drink label 'misleading'". Thelocal.se. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ">Beverage Alcohol Labeling Requirements by Country". Icap.org. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- "Alcohol-free products". Systembolaget.se. 2011-03-11. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- "fifedirect - Licensing & Regulations - Calling Time on Short Measures!". Fifefire.gov.uk. 2008-07-29. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- "Shape of glass and amount of alcohol poured: comparative study of effect of practice and concentration". BMJ. 331 (7531): 1512–14. 2005. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1512.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - George F. Will (2009-10-29). "A reality check on drug use". Washington Post. Washington Post. pp. A19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Rorabaugh, W.J. (1981). The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-502990-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Alcohol powder: Alcopops from a bag, Westdeutsche Zeitung, 28 October 2004 (German)

- https://gust.com/c/alcogel

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 942681, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 942681instead. - "Poisoned tourist saved with vodka drip". NBC News. 2007-10-10. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- Brent J (2001). "Current management of ethylene glycol poisoning". Drugs. 61 (7): 979–88. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161070-00006. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 11434452.

- Brent R. Ekins; et al. (1985). "Standardized Treatment of Severe Methanol Poisoning With Ethanol and Hemodialysis". West J Med. 142 (3): 337–40. PMC 1306022.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ramchandani, V.A.; Kwo, P.Y.; Li, T-K. (2001). "Effect of Food and Food Composition on Alcohol Elimination Rates in Healthy Men and Women" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 41 (12): 1345–50. doi:10.1177/00912700122012814. PMID 11762562.

- "Microsoft Word - global_alcohol_overview_260105.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- "Alcohol". New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

External links

- Alcohol, Health-EU Portal

- BBC Headroom: Drinking too much?

- International Center for Alcohol Policies — Website

- International Center for Alcohol Policies — List of Tables

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism - What Is a Standard Drink?

- Food and alcoholic drinks - Hebrew blog about alcohol

| Alcoholic beverages | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alcohol | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol control |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||||

| Hypnotics/sedatives (N05C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABAA |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GABAB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2-Adrenergic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HT2A |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orexin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2δ VDCC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recreational drug use | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anxiolytics (N05B) | |

|---|---|

| 5-HT1ARTooltip 5-HT1A receptor agonists | |

| GABAARTooltip GABAA receptor PAMsTooltip positive allosteric modulators |

|

| Hypnotics | |

| Gabapentinoids (α2δ VDCC blockers) | |

| Antidepressants |

|

| Antipsychotics | |

| Sympatholytics (Antiadrenergics) |

|

| Others | |

| |

| Drugs which induce euphoria | |

|---|---|

| |

| See also: Recreational drug use |

| Hypnotics/sedatives (N05C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABAA |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GABAB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2-Adrenergic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HT2A |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orexin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2δ VDCC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neurotoxins | |

|---|---|

| Animal toxins | |

| Bacterial | |

| Cyanotoxins | |

| Plant toxins | |

| Mycotoxins | |

| Pesticides | |

| Nerve agents | |

| Bicyclic phosphates | |

| Cholinergic neurotoxins | |

| Psychoactive drugs | |

| Other | |

| Psychoactive substance-related disorders | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||||||||||

| Combined substance use |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Caffeine | |||||||||||||||||

| Cannabis | |||||||||||||||||

| Cocaine | |||||||||||||||||

| Hallucinogen | |||||||||||||||||

| Nicotine | |||||||||||||||||

| Opioids |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Sedative / hypnotic | |||||||||||||||||

| Stimulants | |||||||||||||||||

| Volatile solvent | |||||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||||