This is the current revision of this page, as edited by 2601:1c2:4c00:81a0:ddc8:a86e:86fa:3b9 (talk) at 11:12, 9 January 2025 (Corrected misinformation). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this version.

Revision as of 11:12, 9 January 2025 by 2601:1c2:4c00:81a0:ddc8:a86e:86fa:3b9 (talk) (Corrected misinformation)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Atypical antipsychotic medication Not to be confused with clonazepam or clonidine.Pharmaceutical compound

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Clozaril, Leponex, Versacloz, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a691001 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular |

| Drug class | Atypical antipsychotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–70% |

| Metabolism | Liver, by several CYP isozymes mainly via CYP2D6 |

| Elimination half-life | 4–26 hours (mean value 14.2 hours in steady state conditions) |

| Excretion | 80% in metabolized state: 30% biliary and 50% kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.024.831 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H19ClN4 |

| Molar mass | 326.83 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 183 °C (361 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 0.1889 |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Clozapine, sold under the brand name Clozaril among others, is a psychiatric medication and was the first atypical antipsychotic to be discovered. It is primarily used to treat people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who have had an inadequate response to two other antipsychotics, or who have been unable to tolerate other drugs due to extrapyramidal side effects. In the US, clozapine is also approved for use in people with recurrent suicidal behavior in people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. It is also used for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease.

Clozapine is recommended by multiple international treatment guidelines, after resistance to two other antipsychotic medications, and is the only treatment likely to result in improvement if two (or one) other antipsychotic has not had a satisfactory effect. Long term follow-up studies from Finland show significant improvements in terms of overall mortality including from suicide and all causes. Clozapine is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is available as a generic medication. Common adverse effects include drowsiness, constipation, hypersalivation (increased saliva production), tachycardia, low blood pressure, blurred vision, significant weight gain, and dizziness. Clozapine is not normally associated with tardive dyskinesia (TD) and is recommended as the drug of choice when this is present, although some case reports describe clozapine-induced TD. Serious adverse effects include agranulocytosis, seizures, myocarditis (inflammation of the heart), and hyperglycemia (high blood glucose levels). The use of this drug can rarely result in clozapine-induced gastric hypomotility syndrome which may lead to bowel obstruction and death. The mechanism of action is not entirely clear in the current medical literature.

History

Clozapine was synthesized in 1958 by Wander AG, a Swiss pharmaceutical company, based on the chemical structure of the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine. The first test in humans in 1962 was considered a failure. Trials in Germany in 1965 and 1966 as well as a trial in Vienna in 1966 were successful. In 1967, Wander AG was acquired by Sandoz. Further trials took place in 1972 when clozapine was released in Switzerland and Austria as Leponex. Two years later, it was released in West Germany and in Finland in 1975. Early testing was performed in the United States around the same time. In 1975, 16 cases of agranulocytosis leading to 8 deaths in clozapine-treated patients, reported from 6 hospitals mostly in southwestern Finland, led to concern. Analysis of the Finnish cases revealed that all the agranulocytosis cases had occurred within the first 18 weeks of treatment and the authors proposed blood monitoring during this period. The rate of agranulocytosis in Finland appeared to be 20 times higher than in the rest of the world and there was speculation that this may have been due a unique genetic variant in the region. Whilst the drug continued to be manufactured by Sandoz, and remained available in Europe, development in the U.S. halted.

Interest in clozapine continued in an investigational capacity in the United States because, even in the 1980s, the duration of hospitalization, especially in state hospitals for those with treatment resistant schizophrenia, might often be measured in years rather than days. The role of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia was established by the landmark Clozaril Collaborative Study Group Study #30 in which clozapine showed marked benefits compared to chlorpromazine in a group of patients with protracted psychosis and who had already shown an inadequate response to other antipsychotics. This involved both stringent blood monitoring and a double-blind design with the power to demonstrate superiority over standard antipsychotic treatment. The inclusion criteria were patients who had failed to respond to at least three previous antipsychotics and had then not responded to a single blind treatment with haloperidol (mean dose 61 mg +/− 14 mg/d). Two hundred and sixty-eight were randomised were to double blind trials of clozapine (up to 900 mg/d) or chlorpromazine (up to 1800 mg/d). 30% of the clozapine patients responded compared to 4% of the controls, with significantly greater improvement on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impression Scale, and Nurses' Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation; this improvement included "negative" as well as positive symptom areas. Following this study, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use in 1990. Cautious of this risk, however, the FDA required a black box warning for specific side effects including agranulocytosis, and took the unique step of requiring patients to be registered in a formal system of tracking so that blood count levels could be evaluated on a systematic basis.

In December 2002, clozapine was approved in the US for people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder judged to be at chronic risk for suicidal behavior. In 2005, the FDA approved criteria to allow reduced blood monitoring frequency. In 2015, the individual manufacturer Patient Registries were consolidated by request of the FDA into a single shared patient registry called The Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) Registry. Despite the demonstrated safety of the new FDA monitoring requirements, which have lower neutrophil levels and do not include total white cell counts, international monitoring has not been standardized.

Medical uses

Schizophrenia

The role of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia was established by a 1988 landmark multicenter double blind study in which clozapine (up to 900 mg/d) showed marked benefits compared to chlorpromazine (up to 1800 mg/d) in a group of patients with protracted psychosis who had already shown an inadequate response to at least three previous antipsychotics including a prior single blind trial of haloperidol (mean 61+/− 14 mg/d for six weeks). While there are significant side effects, clozapine remains the most effective treatment when one or more other antipsychotics have had an inadequate response. The use of clozapine is associated with multiple improved outcomes, including a reduced rate of all-cause mortality, suicide and hospitalization. In a 2013 network comparative meta-analysis of 15 antipsychotic drugs, clozapine was found to be significantly more effective than all other drugs. In a 2021 UK study, the majority of patients (over 85% of respondents) who took clozapine preferred it to their previous therapies, felt better on it and wanted to keep taking it. In a 2000 Canadian survey of 130 patients, the majority reported better satisfaction, quality of life, compliance with treatment, thinking, mood, and alertness. UK studies into the perspectives of people taking clozapine and their families following treatment with and discontinuation of clozapine describe significant stress and fearfulness of clozapine being stopped.

Clozapine is usually used for people diagnosed with schizophrenia who have had an inadequate response to other antipsychotics or who have been unable to tolerate other drugs due to extrapyramidal side effects. The US FDA authorisation also includes clozapine for the treatment of people exhibition suicidal behaviour who have schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. It is also used for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease. It is regarded as the gold-standard treatment when other medication has been insufficiently effective and its use is recommended by multiple international treatment guidelines, supported by systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Whilst all current guidelines reserve clozapine for individuals in whom two other antipsychotics have already been tried, evidence indicates that clozapine might instead be used as a second line drug. Clozapine treatment has been demonstrated to produce improved outcomes in multiple domains including; a reduced risk of hospitalisation, a reduced risk of drug discontinuation, a reduction in overall symptoms and has improved efficacy in the treatment of positive psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Despite a range of side effects patients report good levels of satisfaction and long term adherence is favourable compared to other antipsychotics. Very long term follow-up studies reveal multiple benefits in terms of reduced mortality, with a particularly strong effect for reduced death by suicide, clozapine is the only antipsychotic known to have an effect reducing the risk of suicide or attempted suicide. Clozapine has a significant anti-aggressive effect. Clozapine is widely used in secure and forensic mental health settings where improvements in aggression, shortened admission and reductions in restrictive practice such as seclusion have been found. In secure hospitals and other settings clozapine has also been used in the treatment of borderline and antisocial personality disorder when this has been associated with violence or self-harm. Although oral treatment is almost universal clozapine has on occasion been enforced using either nasogastric or a short acting injection although in almost 50% of the approximately 100 reported cases patients agreed to take oral medication prior to the use of a coercive intervention. Clozapine has also been used off-label to treat catatonia with success in over 80% of cases.

Bipolar disorder

On the basis of systematic reviews clozapine is recommended in some treatment guidelines as a third or fourth line treatment for bipolar disorder. A long term follow-up study showed efficacy in terms of both psychiatric and somatic hospitialisation, but with bipolar disorder this effect was not as strong as with some other treatments (olanzapine long-acting injection (LAI) (aHR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.37–0.80), haloperidol LAI (aHR = 0.62, 0.47–0.81), zuclopenthixol LAI (aHR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.52–0.85), lithium (aHR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.71–0.76) and clozapine (aHR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.64–0.87)). Bipolar disorder is an off-label indication for clozapine.

Severe personality disorders

Clozapine is also used in borderline personality disorder and a randomized controlled trial is currently underway. The use of clozapine to treat personality disorders is uncommon and off-label.

Initiation

Whilst clozapine is usually initiated in hospital setting community initiation is also available. Before clozapine can be initiated multiple assessments and baseline investigations are performed. In the UK and Ireland there must be an assessment that the patient satisfies the criteria for prescription; treatment resistant schizophrenia, intolerance due to extrapyramidal symptoms of other antipsychotics or psychosis in Parkinson's disease. Establishing a history of treatment resistance may include careful review of the medication history including the durations, doses and compliance of previous antipsychotic therapy and that these did not have an adequate clinical effect. A diagnostic review may also be performed. That could include review of antipsychotic plasma concentrations if available. The prescriber, patient, pharmacy and the laboratory performing blood counts are all registered with a specified clozapine provider who must be advised that there is no history of neutropenia from any cause. The clozapine providers collaborate by sharing information regarding patients who have had clozapine related neutropenia or agranulocytosis so that clozapine cannot be used again on license. Clozapine may only be dispensed after a satisfactory blood result has been received by the risk monitoring agency at which point an individual prescription may be released to an individual patient only.

Baseline tests usually also include; a physical examination including baseline weight, waist circumference and BMI, assessments of renal function and liver function, an ECG and other baseline bloods may also be taken to facilitate monitoring of possible myocarditis, these might include C reactive protein (CRP) and troponin. In Australia and New Zealand pre-clozapine echocardiograms are also commonly performed. A number of service protocols are available and there are variations in the extent of pre-clozapine work ups. Some might also include fasting lipids, HbA1c and prolactin. At the Maudsley Hospital in the UK the Treat service also routinely performs a wide variety of other investigations including multiple investigations for other causes of psychosis and comorbidities including; MRI brain imaging, thyroid function tests, B12, folate and serum calcium levels, infection screening for blood borne viruses including Hepatitis B and C, HIV and syphilis as well as screening for autoimmune psychosis by anti-NMDA, anti-VGKC and Anti-nuclear antibody screening. Investigations used to monitor the possibility of clozapine related side effects such as myocarditis are also performed including baseline troponin, CRP and BNP, and for neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a CK level may also be drawn.

Other clozapine initiation schedules exist. In 2023 the Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis Working Group published consensus guidelines on clozapine optimisation including initiation. The Team Daniel (Dr Laitman's regimen) includes a much slower than usual titration (25mg increments per week rather than per day) combined with the prescription of a variety of other medications to manage side effects such as nausea, hypersalivation, acid reflux, tachycardia, nocturnal enuresis, metformin and lamotrigine.

The dose of clozapine is initially low and gradually increased over a number of weeks. Initial doses may range from 6.5 to 12.5 mg/d, increasing stepwise typically, to doses in the range of 250–350 mg per day, at which point an assessment of response will be performed. In the UK, the average clozapine dose is 450 mg/d. But response is highly variable and some patients respond at much lower doses, and vice versa. A genome wide association study from the MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics in Cardiff, UK has shown significant interethnic variation in clozapine metabolism due to variation in the frequency of CYP alleles involved in clozapine metabolism such as UGT1A and CYP1A1/1A2. This found faster average clozapine metabolism in people of sub-Saharan African ancestry than in those of European ancestry and that individuals with east Asian or southwest Asian ancestry were more likely to be slow clozapine metabolisers than those with European ancestry.

Monitoring

During the initial dose titration phase, the following are typically monitored, usually daily at first: pulse, blood pressure, and temperature. Since orthostatic hypotension can be problematic, blood pressure should be monitored both sitting and standing. If there is a significant drop then the rate of the dose increase may be slowed.

Mandatory full blood counts are performed weekly for the first 18 weeks. In some services there will also be monitoring of markers that might indicate myocarditis, troponin, CRP and BNP, although the exact tests and frequency vary between services. Weight is usually measured weekly.

Thereon other investigations and monitoring will always include full blood counts (fortnightly for 1 year then monthly). Weight, waist circumference, lipids and glucose or HbA1c may also be monitored.

Clozapine response and treatment optimization

As with other antipsychotics, and in contrast to received wisdom, responses to clozapine are typically seen soon after initiation and often within the first week. That said responses, especially those which are partial, can be delayed. Quite what an adequate trial of clozapine is, is uncertain, but a recommendation is that this should be for at least 8 weeks on a plasma trough level above 350-400 micro g/L. There is considerable inter-individual variation. A significant number of patients respond at lower and also much higher plasma concentrations and some patients, especially young male smokers may never achieve these plasma levels even at doses of 900 mg/day. Options then include either increasing the dose above the licensed maximum or the addition of a drug that inhibits clozapine metabolism. Avoiding unnecessary polypharmacy is a general principle in drug treatment.

Optimizing blood sampling

The neutrophil cut off for clozapine have shown an exceptional ability to mitigate the risk of neutropenia and agranulocytosis. There is a significant margin of safety. Some patients may have marginal neutrophil counts before and after initiation and they are at risk of premature clozapine discontinuation. A knowledge of neutrophil biology allows blood sampling optimisation. Neutrophils show a diurnal variation in response to the natural cycle of G-CSF production, they are increased in the afternoons, they are also mobilised into the circulation after exercise and smoking. Simply shifting blood sampling has been shown to avoid unnecessary discontinuations, especially in black populations. However this is a disruption to usual hospital practice. Other practical steps are to ensure that blood results become available in hours and when senior staff are available.

Underuse of clozapine

Clozapine is widely recognised as being underused with wide variation in prescribing, especially in patients with African heritage.

Psychiatrists' prescribing practices have been found to be the most significant variable regarding variance in its use. Surveys of psychiatrists' attitudes to clozapine have found that many had little experience in its use, overestimated the incidence of side effects, and did not appreciate that many patients prefer to take clozapine over other antipsychotics. In contrast to many psychiatrists' expectations most patients believe that the blood testing and other difficulties are worth the multiple benefits that they perceive. Whilst psychiatrists fear the severe adverse effects such as agranulocytosis, patients are more concerned about hypersalivation. Clozapine is no longer actively marketed and this may also be one of the explanations for its underuse.

Despite the strong evidence and universal endorsement by national and international treatment guidelines and the experiences of patients themselves, most people eligible for clozapine are not treated with it. A large study in England found that approximately 30% of those eligible for clozapine were being treated with it. Those patients that do start clozapine usually face prolonged delay, multiple episodes of psychosis and treatments such as high dose antipsychotics or polypharmacy. Instead of two previous antipsychotics many will have been exposed to ten or more drugs which were not effective. A study of 120 patients conducted in four hospitals in South-East London found a mean of 9.2 episodes of antipsychotic prescription before clozapine was initiated and the mean delay in using clozapine was 5 years. Treatments that have no evidence base or are regarded as actively harmful are used instead.

As well as variation within counties there is massive variation in the use of clozapine internationally. An international study of 17 counties found greatest use in Finland (189/100,000 persons) and New Zealand (116/100,000), and least in the Japanese cohort (0.6/100,000) and in the privately insured US cohort (14/100,000).

Racial disparity in the use of clozapine

A general finding in healthcare provision is that minority groups receive inferior treatment; this is a particular finding in the US. In the US a general finding is that compared to their white peers African American people are less likely to be prescribed the second generation antipsychotics, which are more expensive than alternatives and this was even apparent and especially so for clozapine when comparison was made in the Veterans Affairs medical system and when differences regarding socioeconomic factors were taken into account. As well as being less likely to start clozapine black patients are more likely to stop clozapine, possibly on account of benign ethnic neutropenia.

Benign ethnic neutropenia

Benign reductions in neutrophils are observed in individuals of all ethnic backgrounds. Ethnic neutropenia (BEN), neutropenia without immune dysfunction or increased liability to infection, is not due to abnormal neutrophil production; although, the exact aetiology of the reduction in circulating cells remains unknown. BEN is associated with several ethnic groups, but in particular those with Black African and West African ancestry. A difficulty with the use of clozapine is that neutrophil counts have been standardised on white populations. For significant numbers of black patients the standard neutrophil count thresholds did not permit clozapine use, as the thresholds did not take BEN into account. Since 2002, clozapine monitoring services in the UK have used reference ranges 0.5 × 10/l lower for patients with haematologically confirmed BEN and similar adjustments are available in the current US criteria, although with lower permissible minima. But even then significant numbers of black patients will not be eligible even though the low neutrophil counts do not in their case reflect disease. The Duffy–Null polymorphism, which protects against some types of malaria, is predictive of BEN. In the UK the Royal College of Psychiatrists recommends consideration of Duffy typing when using or considering clozapine for people with Black or Middle Eastern ancestry, in the UK this can be requested from the International Blood Group Reference laboratory based in Bristol.

Adverse effects

Clozapine may cause serious and potentially fatal adverse effects. Clozapine carries five black box warnings, including (1) severe neutropenia (low levels of neutrophils), (2) orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure upon changing positions), including slow heart rate and fainting, (3) seizures, (4) myocarditis (inflammation of the heart), and (5) risk of death when used in elderly people with dementia-related psychosis. Lowering of the seizure threshold may be dose related. Increasing the dose slowly may decrease the risk for seizures and orthostatic hypotension.

Common effects include constipation, bed-wetting, night-time drooling, muscle stiffness, sedation, tremors, orthostatic hypotension, high blood sugar, and weight gain. The risk of developing extrapyramidal symptoms, such as tardive dyskinesia, is below that of typical antipsychotics; this may be due to clozapine's anticholinergic effects. Extrapyramidal symptoms may subside somewhat after a person switches from another antipsychotic to clozapine. Sexual problems, such as retrograde ejaculation and priapism, have been reported while taking clozapine. Rare adverse effects include periorbital edema and hematological malignancy. Despite the risk for numerous side effects, many side effects can be managed while continuing to take clozapine.

Mortality

The overall all cause mortality for people with serious psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia who are prescribed clozapine is lower than those who take other treatments and much lower than those who take no drug treatments at all. Reductions are particularly marked for death by suicide but also from all natural causes. This is demonstrated by studies which have used whole-population databases, such as those completed in Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Taiwan and following systematic review and meta-analysis.

Neutropenia and agranulocytosis

Main article: AgranulocytosisClozapine use has been associated with neutropenia, and as a result clozapine therapy is typically done with stringent blood monitoring. However, meta-analysis of controlled trial data fails to show that clozapine has a stronger association with neutropenia than other antipsychotic medications, or to find a difference in rates of agranulocytosis before and after 1990 (at which point mandatory monitoring was introduced). Overall, despite the concerns relating to blood and other side effects, clozapine use is associated with a reduced mortality, especially from suicide which is a major cause of premature death in people with schizophrenia. The risk of clozapine related agranulocytosis and neutropenia warranted the mandatory use of stringent risk monitoring and management systems, which have reduced the risk of death from these adverse events to around 1 in 7,700. The association between clozapine use and specific blood dyscrasias was first noted in the 1970s when eight deaths from agranulocytosis were noted in Finland. At the time it was not clear if this exceeded the established rate of this side effect which is also found in other antipsychotics and although the drug was not completely withdrawn, its use became limited.

Clozapine Induced Neutropenia (CIN) occurs in approximately 3.8% of cases and Clozapine Induced Agranulocytosis (CIA) in 0.4%. These are potentially serious side effects and agranulocytosis can result in death. To mitigate this risk clozapine is only used with mandatory absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring (neutrophils are the most abundant of the granulocytes); for example, in the United States, the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). The exact schedules and blood count thresholds vary internationally and the thresholds at which clozapine can be used in the U.S. has been lower than those currently used in the U.K. and Australasia for some time. The effectiveness of the risk management strategies used is such that deaths from these side effects are very rare occurring at approximately 1 in 7700 patients treated. Almost all the adverse blood reactions occur within the first year of treatment and the majority within the first 18 weeks. After one year of treatment these risks reduce markedly to that seen in other antipsychotic drugs 0.01% or about 1 in 10,000 and the risk of death is markedly lower still. When reductions in neutrophil levels are noted on regular blood monitoring then, depending on the value, monitoring may be increased or, if the neutrophil count is sufficiently low, then clozapine is stopped immediately and can then no longer be used within the medicinal licence. Stopping clozapine almost always results in resolution of the neutrophil reduction. However severe agranulocytosis can result in spontaneous infection and death, is a severe decrease in the amount of a specific kind of white blood cell called granulocytes. Clozapine carries a black box warning for drug-induced agranulocytosis, although meta-analysis of controlled studies comparing the association between clozapine and other antipsychotic medications and the development of neutropenia fails to show a specific clozapine related risk, which is contrary to the previously accepted beliefs. Rapid point-of-care tests may simplify the monitoring for agranulocytosis.

Pharmacogenetics and Mechanism of Clozapine Related Blood Dyscrasias

CIA is a type B idiosyncratic adverse drug reaction (ADR). It is unrelated to the mode of therapeutic action, and there is no evidence that it is dose dependent and is one of many non-chemotherapy drugs with the potential to induce an idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis (IDIN). The mechanisms of CIA have not been fully elucidated but are thought to involve a combination of toxic, immunological and genetic factors, combined with oxidised drug metabolites and HLA-activating T helper cells, which induce B cells to produce drug-dependent neutrophil antibodies. Severe life-threatening CIA has a distinctive pattern, with a continuous and rapid fall to zero or near-zero ANC within 2–15 days, followed by a prolonged nadir of a similar duration. Genetic linkage studies have identified specific HLA types and transporter genes as conferring increased risk, but the pharmacogenetics has not yet progressed so as to make testing sufficiently predictive to be used clinically, and the identified genetic risk factors are not generalisable across ethnic groups. Overall, IDINs now have a mortality estimated at 5%; this is a marked improvement compared with previous levels, owing to early recognition and the introduction of hematopoietic growth factors such as G-CSF (granulocyte colony stimulating factor).

Clozapine-induced neutropenia (CIN) and CIA are often regarded as synonymous, with the belief that CIN is a precursor to the more serious dyscrasia. However, there is little if any evidence to support this idea. Instead, it seems that the two are distinct, with most cases of CIN being incidental findings and artefacts of increased blood monitoring.

International Variation and Cost effectiveness of Monitoring

There is very significant international variation in the frequency of full blood count (for neutrophil counts) monitoring including both the thresholds for increased monitoring and for clozapine withdrawal as well as the duration and frequency of blood testing. The most extreme variation is between Iceland, where clozapine is given without full blood monitoring, and with no demonstrable increase in risk and Japan, where the thresholds and frequency is highest. Likewise there are differences between the US thresholds and those in the UK. The US and UK thresholds for clozapine monitoring were identical until 2015, at which point the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a reduction of 0.5 × 10/L for each ANC range and removed the requirement for white blood cell, eosinophil and platelet monitoring completely. The frequency used in many parts of mainland Europe and the reduced US thresholds and alternate, extended intervals in monitoring used in the Netherlands have had no demonstrable increase in risk. The rationale for monitoring after the first 18 weeks of treatment is questionable, given that monthly blood sampling is highly unlikely to detect the sudden and profound falls in ANC that accompany agranulocytosis and the economic analysis of the cost effectiveness of the current clozapine monitoring schedules shows that these are of highly questionable utility. Similarly several other drugs, for example carbimazole, which is commonly used in medical practice and with very similar risks of agranulocytosis is used without mandatory FBC monitoring.

Clozapine rechallenge

A clozapine "rechallenge" is when someone that experienced agranulocytosis while taking clozapine starts taking the medication again. In countries in which the neutrophil thresholds are higher than those used in the US a simple approach is, if the lowest ANC had been above the US cut off, to reintroduce clozapine but with the US monitoring regime. This has been demonstrated in a large cohort of patients in a hospital in London in which it was found that of 115 patients who had had clozapine stopped according to the US criteria only 7 would have had clozapine stopped if the US cut offs had been used. Of these 62 were rechallenged, 59 continued to use clozapine without difficulty and only 1 had a fall in neutrophils below the US cut off. Other approaches have included the use of other drugs to support neutrophil counts including lithium or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). However, if agranulocytosis still occurs during a rechallenge, the alternative options are limited.

Cardiac toxicity

Clozapine can rarely cause myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. A large meta-analysis of clozapine exposure to over 250,000 people revealed that these occurred in approximately 7 in 1000 patients treated and resulted in death in 3 and 4 in 10,000 patients exposed respectively and although myocarditis occurred almost exclusively within the first 8 weeks of treatment, cardiomyopathy can occur much later on. First manifestations of illness are fever which may be accompanied by symptoms associated with upper respiratory tract, gastrointestinal or urinary tract infection. Typically C-reactive protein (CRP) increases with the onset of fever, and rises in the cardiac enzyme, troponin, occur up to 5 days later. Monitoring guidelines advise checking CRP and troponin at baseline and weekly for the first 4 weeks after clozapine initiation and observing the patient for signs and symptoms of illness. Signs of heart failure are less common and may develop with the rise in troponin. A recent case-control study found that the risk of clozapine-induced myocarditis is increased with increasing rate of clozapine dose titration, increasing age and concomitant sodium valproate. A large electronic health register study has revealed that nearly 90% of cases of suspected clozapine related myocarditis are false positives. Rechallenge after clozapine induced myocarditis has been performed and a protocol for this specialist approach has been published. A systematic review of rechallenge after myocarditis has shown success in over 60% of reported cases.

Gastrointestinal hypomotility

Another underrecognized and potentially life-threatening effect spectrum is gastrointestinal hypomotility, which may manifest as severe constipation, fecal impaction, paralytic ileus, bowel obstruction, acute megacolon, ischemia or necrosis. Colonic hypomotility has been shown to occur in up to 80% of people prescribed clozapine when gastrointestinal function is measured objectively using radiopaque markers. Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility currently has a higher mortality rate than the better known side effect of agranulocytosis. A Cochrane review found little evidence to help guide decisions about the best treatment for gastrointestinal hypomotility caused by clozapine and other antipsychotic medication. Monitoring bowel function and the preemptive use of laxatives for all clozapine-treated people has been shown to improve colonic transit times and reduce serious sequelae.

Hypersalivation

Hypersalivation, or the excessive production of saliva, is one of the most common adverse effects of clozapine (30–80%). The saliva production is especially bothersome at night and first thing in the morning, as the immobility of sleep precludes the normal clearance of saliva by swallowing that occurs throughout the day. While clozapine is a muscarinic antagonist at the M1, M2, M3, and M5 receptors, clozapine is a full agonist at the M4 subset. Because M4 is highly expressed in the salivary gland, its M4 agonist activity is thought to be responsible for hypersalivation. clozapine-induced hypersalivation is likely a dose-related phenomenon, and tends to be worse when first starting the medication. Besides decreasing the dose or slowing the initial dose titration, other interventions that have shown some benefit include systemically absorbed anticholinergic medications such as hyoscine, diphenhydramine and topical anticholinergic medications like ipratropium bromide. Mild hypersalivation may be managed by sleeping with a towel over the pillow at night.

Central nervous system

CNS side effects include drowsiness, vertigo, headache, tremor, syncope, sleep disturbances, nightmares, restlessness, akinesia, agitation, seizures, rigidity, akathisia, confusion, fatigue, insomnia, hyperkinesia, weakness, lethargy, ataxia, slurred speech, depression, myoclonic jerks, and anxiety. Rarely seen are delusions, hallucinations, delirium, amnesia, libido increase or decrease, paranoia and irritability, abnormal EEG, worsening of psychosis, paresthesia, status epilepticus, and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Similar to other antipsychotics, clozapine rarely has been known to cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Urinary incontinence

Clozapine is linked to urinary incontinence, though its appearance may be under-recognized. This side-effect may be amendable to bethanechol.

Withdrawal effects

Abrupt withdrawal may lead to cholinergic rebound effects, such as indigestion, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, overabundance of saliva, profuse sweating, insomnia, and agitation. Abrupt withdrawal can also cause severe movement disorders, catatonia, and psychosis. Doctors have recommended that patients, families, and caregivers be made aware of the symptoms and risks of abrupt withdrawal of clozapine. When discontinuing clozapine, gradual dose reduction is recommended to reduce the intensity of withdrawal effects.

Weight gain and diabetes

In addition to hyperglycemia, significant weight gain is frequently experienced by patients treated with clozapine. Impaired glucose metabolism and obesity have been shown to be constituents of the metabolic syndrome and may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. The data suggest that clozapine may be more likely to cause adverse metabolic effects than some of the other atypical antipsychotics. For people who gain weight because of clozapine, taking metformin may reportedly improve three of the five components of the metabolic syndrome: waist circumference, fasting glucose, and fasting triglycerides.

Pneumonia

International adverse drug effect databases indicate that clozapine use is associated with a significantly increased incidence of and death from pneumonia and this may be one of the most significant adverse events. The mechanisms for this are unknown although it has been speculated that it may be related to hypersalivation or the immune effects of clozapine's effects on the resolution of inflammation.

Overdose

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2019) |

Symptoms of overdose can be variable, but often include; sedation, confusion, tachycardia, seizures and ataxia. Fatalities have been reported due to clozapine overdose, though overdoses of greater than 5000 mg have been survived.

Drug interactions

Fluvoxamine inhibits the metabolism of clozapine leading to significantly increased blood levels of clozapine.

When carbamazepine is concurrently used with clozapine, it has been shown to decrease plasma levels of clozapine significantly thereby decreasing the beneficial effects of clozapine. Patients should be monitored for "decreased therapeutic effects of clozapine if carbamazepine" is started or increased. If carbamazepine is discontinued or the dose of carbamazepine is decreased, therapeutic effects of clozapine should be monitored. The study recommends carbamazepine to not be used concurrently with clozapine due to increased risk of agranulocytosis.

Ciprofloxacin is an inhibitor of CYP1A2 and clozapine is a major CYP1A2 substrate. Randomized study reported elevation in clozapine concentration in subjects concurrently taking ciprofloxacin. Thus, the prescribing information for clozapine recommends "reducing the dose of clozapine by one-third of original dose" when ciprofloxacin and other CYP1A2 inhibitors are added to therapy, but once ciprofloxacin is removed from therapy, it is recommended to return clozapine to original dose.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

See also: Atypical antipsychotic § Pharmacodynamics, and Antipsychotic § Comparison of medications| Protein | CZP Ki (nM) | NDMCTooltip N-Desmethylclozapine Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 123.7 | 13.9 |

| 5-HT1B | 519 | 406.8 |

| 5-HT1D | 1,356 | 476.2 |

| 5-HT2A | 5.35 | 10.9 |

| 5-HT2B | 8.37 | 2.8 |

| 5-HT2C | 9.44 | 11.9 |

| 5-HT3 | 241 | 272.2 |

| 5-HT5A | 3,857 | 350.6 |

| 5-HT6 | 13.49 | 11.6 |

| 5-HT7 | 17.95 | 60.1 |

| α1A | 1.62 | 104.8 |

| α1B | 7 | 85.2 |

| α2A | 37 | 137.6 |

| α2B | 26.5 | 95.1 |

| α2C | 6 | 117.7 |

| β1 | 5,000 | 6,239 |

| β2 | 1,650 | 4,725 |

| D1 | 266.25 | 14.3 |

| D2 | 157 | 101.4 |

| D3 | 269.08 | 193.5 |

| D4 | 26.36 | 63.94 |

| D5 | 255.33 | 283.6 |

| H1 | 1.13 | 3.4 |

| H2 | 153 | 345.1 |

| H3 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| H4 | 665 | 1,028 |

| M1 | 6.17 | 67.6 |

| M2 | 36.67 | 414.5 |

| M3 | 19.25 | 95.7 |

| M4 | 15.33 | 169.9 |

| M5 | 15.5 | 35.4 |

| SERTTooltip Serotonin transporter | 1,624 | 316.6 |

| NETTooltip Norepinephrine transporter | 3,168 | 493.9 |

| DATTooltip Dopamine transporter | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. All data are for cloned human proteins. | ||

Clozapine is classified as an atypical antipsychotic drug because it binds to serotonin as well as dopamine receptors. It acts as an antagonist at both receptors.

Clozapine is an inverse agonist at the 5-HT2A subtype of the serotonin receptor, putatively improving depression, anxiety, and the negative cognitive symptoms associated with schizophrenia.

A direct interaction of clozapine with the GABAB receptor has also been shown. GABAB receptor-deficient mice exhibit increased extracellular dopamine levels and altered locomotor behaviour equivalent to that in schizophrenia animal models. GABAB receptor agonists and positive allosteric modulators reduce the locomotor changes in these models.

Clozapine induces the release of glutamate and D-serine, an agonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, from astrocytes, and reduces the expression of astrocytic glutamate transporters. These are direct effects that are also present in astrocyte cell cultures not containing neurons. Clozapine prevents impaired NMDA receptor expression caused by NMDA receptor antagonists.

Pharmacokinetics

The absorption of clozapine is almost complete following oral administration, but the oral bioavailability is only 60 to 70% due to first-pass metabolism. The time to peak concentration after oral dosing is about 2.5 hours, and food does not appear to affect the bioavailability of clozapine. However, it was shown that co-administration of food decreases the rate of absorption. The elimination half-life of clozapine is about 14 hours at steady state conditions (varying with daily dose).

Clozapine is extensively metabolized in the liver, via the cytochrome P450 system, to polar metabolites suitable for elimination in the urine and feces. The major metabolite, norclozapine (desmethyl-clozapine), is pharmacologically active. The cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 1A2 is primarily responsible for clozapine metabolism, but 2C, 2D6, 2E1 and 3A3/4 appear to play roles as well. Agents that induce (e.g., cigarette smoke) or inhibit (e.g., theophylline, ciprofloxacin, fluvoxamine) CYP1A2 may increase or decrease, respectively, the metabolism of clozapine. For example, the induction of metabolism caused by smoking means that smokers require up to double the dose of clozapine compared with non-smokers to achieve an equivalent plasma concentration.

Clozapine and norclozapine (desmethyl-clozapine) plasma levels may also be monitored, though they show a significant degree of variation and are higher in women and increase with age. Monitoring of plasma levels of clozapine and norclozapine has been shown to be useful in assessment of compliance, metabolic status, prevention of toxicity, and in dose optimisation.

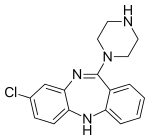

Chemistry

Clozapine is a dibenzodiazepine that is structurally very similar to loxapine (originally deemed a typical antipsychotic). It is slightly soluble in water, soluble in acetone, and highly soluble in chloroform. Its solubility in water is 0.1889 mg/L (25 °C). Its manufacturer, Novartis, claims a solubility of <0.01% in water (<100 mg/L).

| A | Alemoxan, Azaleptine, Azaleptol |

| C | Cloment, Clonex, Clopin, Clopine, Clopsine, Cloril, Clorilex, Clozamed, Clozapex, Clozapin, Clozapina, Clozapinum, Clozapyl, Clozarem, Clozaril |

| D | Denzapine, Dicomex |

| E | Elcrit, Excloza |

| F | FazaClo, Froidir |

| I | Ihope |

| K | Klozapol |

| L | Lanolept, Lapenax, Leponex, Lodux, Lozapine, Lozatric, Luften |

| M | Medazepine, Mezapin |

| N | Nemea, Nirva |

| O | Ozadep, Ozapim |

| R | Refract, Refraxol |

| S | Sanosen, Schizonex, Sensipin, Sequax, Sicozapina, Sizoril, Syclop, Syzopin |

| T | Tanyl |

| U | Uspen |

| V | Versacloz |

| X | Xenopal |

| Z | Zaclo, Zapenia, Zapine, Zaponex, Zaporil, Ziproc, Zopin |

Economics

Despite the expense of the risk monitoring and management systems required, clozapine use is highly cost effective, with a number of studies suggesting savings of tens of thousands of dollars per patient per year compared to other antipsychotics, as well as advantages regarding improvements in quality of life. Clozapine is available as a generic medication.

References

- ^ "Clozapine International Brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Clozaril- clozapine tablet". DailyMed. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Hopfinger AJ, Esposito EX, Llinàs A, Glen RC, Goodman JM (January 2009). "Findings of the challenge to predict aqueous solubility". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 49 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1021/ci800436c. PMID 19117422.

- Stahl SM, Meyer JM (16 May 2019). The Clozapine Handbook. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108553575. ISBN 978-1-108-44746-1. OCLC 1222779588.

- ^ "Information on Clozapine". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 9 August 2024.

- ^ "Clozaril 25 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". www.medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Great Britain). Parkinson's disease in adults : diagnosis and management : full guideline. OCLC 1105250833.

- ^ Kahn RS, Winter van Rossum I, Leucht S, McGuire P, Lewis SW, Leboyer M, et al. (October 2018). "Amisulpride and olanzapine followed by open-label treatment with clozapine in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder (OPTiMiSE): a three-phase switching study". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (10): 797–807. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30252-9. PMID 30115598. S2CID 52014623.

- ^ Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, et al. (July 2012). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 13 (5): 318–378. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.696143. PMID 22834451. S2CID 20370225.

- ^ Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, et al. (January 2010). "The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 71–93. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp116. PMC 2800144. PMID 19955390.

- ^ Gaebel W, Weinmann S, Sartorius N, Rutz W, McIntyre JS (September 2005). "Schizophrenia practice guidelines: international survey and comparison". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 187 (3): 248–255. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.3.248. PMID 16135862.

- ^ Kuipers E, Yesufu-Udechuku A, Taylor C, Kendall T (February 2014). "Management of psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance". BMJ. 348: g1173. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1173. PMID 24523363. S2CID 44282161.

- ^ Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, de Bartolomeis A, van Beveren NJ, Birnbaum ML, et al. (March 2017). "Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group Consensus Guidelines on Diagnosis and Terminology". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 174 (3): 216–229. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050503. PMC 6231547. PMID 27919182.

- ^ Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, Humberstone V, Jablensky A, Killackey E, et al. (May 2016). "Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 50 (5): 410–472. doi:10.1177/0004867416641195. PMID 27106681.

- Remington G, Addington D, Honer W, Ismail Z, Raedler T, Teehan M (September 2017). "Guidelines for the Pharmacotherapy of Schizophrenia in Adults". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 62 (9): 604–616. doi:10.1177/0706743717720448. PMC 5593252. PMID 28703015.

- ^ Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Mehtälä J, Vattulainen P, Correll CU, Tiihonen J (February 2020). "20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20)". World Psychiatry. 19 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1002/wps.20699. PMC 6953552. PMID 31922669.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Clozapine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Pardis P, Remington G, Panda R, Lemez M, Agid O (October 2019). "Clozapine and tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 33 (10): 1187–1198. doi:10.1177/0269881119862535. PMID 31347436. S2CID 198912192.

- Hartling L, Abou-Setta AM, Dursun S, Mousavi SS, Pasichnyk D, Newton AS (October 2012). "Antipsychotics in adults with schizophrenia: comparative effectiveness of first-generation versus second-generation medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (7): 498–511. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00525. PMID 22893011.

- "Clozaril, Fazaclo ODT, Versacloz (clozapine): Drug Safety Communication - FDA Strengthens Warning That Untreated Constipation Can Lead to Serious Bowel Problems". FDA. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Crilly J (March 2007). "The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysis". History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335. PMID 17580753. S2CID 21086497.

- Ellenbroek BA, Cools AR (6 December 2012). Atypical Antipsychotics. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-0348-8448-8 – via Google Books.

- Idänpään-Heikkilä J, Alhava E, Olkinuora M, Palva I (September 1975). "Letter: Clozapine and agranulocytosis". Lancet. 2 (7935): 611. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90206-8. PMID 51442. S2CID 54345964.

- Amsler HA, Teerenhovi L, Barth E, Harjula K, Vuopio P (October 1977). "Agranulocytosis in patients treated with clozapine. A study of the Finnish epidemic". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 56 (4): 241–248. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb00224.x. PMID 920225. S2CID 24782844.

- ^ Griffith RW, Saameli K (October 1975). "Letter: Clozapine and agranulocytosis". Lancet. 2 (7936): 657. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90135-X. PMID 52022. S2CID 53296036.

- Legge SE, Walters JT (March 2019). "Genetics of clozapine-associated neutropenia: recent advances, challenges and future perspective". Pharmacogenomics. 20 (4): 279–290. doi:10.2217/pgs-2018-0188. PMC 6563116. PMID 30767710.

- ^ de With SA, Pulit SL, Staal WG, Kahn RS, Ophoff RA (July 2017). "More than 25 years of genetic studies of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis". The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 17 (4): 304–311. doi:10.1038/tpj.2017.6. PMID 28418011. S2CID 5007914.

- ^ Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H (September 1988). "Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 45 (9): 789–796. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. PMID 3046553.

- Healy D (8 May 2018). The Psychopharmacologists. CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9780203736159. ISBN 978-0-203-73615-9.

- "Supplemental NDA Approval Letter for Clozaril, NDA 19-758 / S-047" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. 18 December 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Letter to Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- "FDA Modifies REMS Program for Clozapine". www.raps.org. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- Sultan RS, Olfson M, Correll CU, Duncan EJ (25 October 2017). "Evaluating the Effect of the Changes in FDA Guidelines for Clozapine Monitoring". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 78 (8): e933 – e939. doi:10.4088/jcp.16m11152. PMC 5669833. PMID 28742291.

- ^ Nielsen J, Young C, Ifteni P, Kishimoto T, Xiang YT, Schulte PF, et al. (February 2016). "Worldwide Differences in Regulations of Clozapine Use". CNS Drugs. 30 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0311-1. PMID 26884144. S2CID 23395968.

- ^ Oloyede E, Casetta C, Dzahini O, Segev A, Gaughran F, Shergill S, et al. (July 2021). "There Is Life After the UK Clozapine Central Non-Rechallenge Database". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 47 (4): 1088–1098. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbab006. PMC 8266568. PMID 33543755.

- "clozapine (CHEBI:3766)". www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Masuda T, Misawa F, Takase M, Kane JM, Correll CU (October 2019). "Association With Hospitalization and All-Cause Discontinuation Among Patients With Schizophrenia on Clozapine vs Other Oral Second-Generation Antipsychotics: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies". JAMA Psychiatry. 76 (10): 1052–1062. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1702. PMC 6669790. PMID 31365048.

- ^ "'Last resort' antipsychotic remains the gold standard for treatment-resistant schizophrenia". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). 2 October 2019. doi:10.3310/signal-000826. S2CID 241225484.

- Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ Taylor D, Shapland L, Laverick G, Bond J, Munro J (December 2000). "Clozapine – a survey of patient perceptions". Psychiatric Bulletin. 24 (12): 450–452. doi:10.1192/pb.24.12.450. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ^ Waserman J, Criollo M (May 2000). "Subjective experiences of clozapine treatment by patients with chronic schizophrenia". Psychiatric Services. 51 (5): 666–668. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.5.666. PMID 10783189.

- Oloyede E, Dunnett D, Taylor D, Clark I, MacCabe JH, Whiskey E, et al. (June 2023). "The lived experience of clozapine discontinuation in patients and carers following suspected clozapine-induced neutropenia". BMC Psychiatry. 23 (1): 413. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-04902-w. PMC 10249299. PMID 37291505.

- Southern J, Elliott P, Maidment I (May 2023). "What are patients' experiences of discontinuing clozapine and how does this impact their views on subsequent treatment?". BMC Psychiatry. 23 (1): 353. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-04851-4. PMC 10204301. PMID 37217959.

- Essali A, Al-Haj Haasan N, Li C, Rathbone J, et al. (Cochrane Schizophrenia Group) (January 2009). "Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (1): CD000059. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059.pub2. PMC 7065592. PMID 19160174.

- Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S (November 2016). "Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 209 (5): 385–392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261. PMID 27388573.

- Nyakyoma K, Morriss R (2010). "Effectiveness of clozapine use in delaying hospitalization in routine clinical practice: a 2 year observational study". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 43 (2): 67–81. PMID 21052043.

- Siskind D, Reddel T, MacCabe JH, Kisely S (June 2019). "The impact of clozapine initiation and cessation on psychiatric hospital admissions and bed days: a mirror image cohort study". Psychopharmacology. 236 (6): 1931–1935. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-5179-6. PMID 30715572. S2CID 59603040.

- Gaszner P, Makkos Z (May 2004). "Clozapine maintenance therapy in schizophrenia". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 28 (3): 465–469. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.011. PMID 15093952. S2CID 36098336.

- Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, et al. (August 2009). "11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study)". Lancet. 374 (9690): 620–627. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. PMID 19595447. S2CID 27282281.

- Taipale H, Lähteenvuo M, Tanskanen A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tiihonen J (January 2021). "Comparative Effectiveness of Antipsychotics for Risk of Attempted or Completed Suicide Among Persons With Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 47 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa111. PMC 7824993. PMID 33428766.

- ^ Brown D, Larkin F, Sengupta S, Romero-Ureclay JL, Ross CC, Gupta N, et al. (October 2014). "Clozapine: an effective treatment for seriously violent and psychopathic men with antisocial personality disorder in a UK high-security hospital". CNS Spectrums. 19 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1017/S1092852914000157. PMC 4255317. PMID 24698103.

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P, Citrome L, Bark N, Cooper TB (June 2006). "Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (6): 622–629. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.622. PMID 16754835.

- Dalal B, Larkin E, Leese M, Taylor PJ (June 1999). "Clozapine treatment of long-standing schizophrenia and serious violence: a two-year follow-up study of the first 50 patients treated with clozapine in Rampton high security hospital". Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 9 (2): 168–178. doi:10.1002/cbm.304.

- Topiwala A, Fazel S (January 2011). "The pharmacological management of violence in schizophrenia: a structured review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (1): 53–63. doi:10.1586/ern.10.180. PMID 21158555. S2CID 2190383.

- Frogley C, Taylor D, Dickens G, Picchioni M (October 2012). "A systematic review of the evidence of clozapine's anti-aggressive effects". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (9): 1351–1371. doi:10.1017/S146114571100201X. PMID 22339930.

- Thomson LD (July 2000). "Management of schizophrenia in conditions of high security". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 6 (4): 252–260. doi:10.1192/apt.6.4.252. ISSN 1355-5146.

- ^ Silva E, Till A, Adshead G (July 2017). "Ethical dilemmas in psychiatry: When teams disagree". BJPsych Advances. 23 (4): 231–239. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.116.016147.

- ^ Silva E, Higgins M, Hammer B, Stephenson P (June 2020). "Clozapine rechallenge and initiation despite neutropenia- a practical, step-by-step guide". BMC Psychiatry. 20 (1): 279. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02592-2. PMC 7275543. PMID 32503471.

- ^ Till A, Selwood J, Silva E (February 2019). "The assertive approach to clozapine: nasogastric administration". BJPsych Bulletin. 43 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1192/bjb.2018.61. PMC 6327298. PMID 30223913.

- ^ Fisher WA (January 2003). "Elements of successful restraint and seclusion reduction programs and their application in a large, urban, state psychiatric hospital". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 9 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00003. PMID 15985912. S2CID 2926142.

- ^ Kasinathan J, Mastroianni T (December 2007). "Evaluating the use of enforced clozapine in an Australian forensic psychiatric setting: two cases". BMC Psychiatry. 7 (S1): 13. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-7-s1-p13. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 3332745.

- Swinton M, Haddock A (January 2000). "Clozapine in Special Hospital: a retrospective case-control study". The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 11 (3): 587–596. doi:10.1080/09585180010006205. ISSN 0958-5184. S2CID 58172685.

- ^ Silva E, Higgins M, Hammer B, Stephenson P (January 2021). "Clozapine re-challenge and initiation following neutropenia: a review and case series of 14 patients in a high-secure forensic hospital". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 11: 20451253211015070. doi:10.1177/20451253211015070. PMC 8221694. PMID 34221348.

- "Schizophrenia, Violence, Clozapine and Risperidone: a Review". British Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (S31): 21–30. December 1996. doi:10.1192/s0007125000298589. ISSN 0007-1250. S2CID 199026883.

- ^ Swinton M (January 2001). "Clozapine in severe borderline personality disorder". The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 12 (3): 580–591. doi:10.1080/09585180110091994. ISSN 0958-5184. S2CID 144701732.

- ^ Haw C, Stubbs J (November 2011). "Medication for borderline personality disorder: a survey at a secure hospital". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 15 (4): 280–285. doi:10.3109/13651501.2011.590211. PMID 22122000. S2CID 43305.

- Henry R, Massey R, Morgan K, Deeks J, Macfarlane H, Holmes N, et al. (December 2020). "Evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of intramuscular clozapine injection: illustrative case series". BJPsych Bulletin. 44 (6): 239–243. doi:10.1192/bjb.2020.6. PMC 7684781. PMID 32081110.

- Casetta C, Oloyede E, Whiskey E, Taylor DM, Gaughran F, Shergill SS, et al. (September 2020). "A retrospective study of intramuscular clozapine prescription for treatment initiation and maintenance in treatment-resistant psychosis" (PDF). The British Journal of Psychiatry. 217 (3): 506–513. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.115. PMID 32605667. S2CID 220287156.

- Lokshin P, Lerner V, Miodownik C, Dobrusin M, Belmaker RH (October 1999). "Parenteral clozapine: five years of experience". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (5): 479–480. doi:10.1097/00004714-199910000-00018. PMID 10505595.

- Schulte PF, Stienen JJ, Bogers J, Cohen D, van Dijk D, Lionarons WH, et al. (November 2007). "Compulsory treatment with clozapine: a retrospective long-term cohort study". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 30 (6): 539–545. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.09.003. PMID 17928054.

- McLean G, Juckes L (1 December 2001). "Parenteral Clozapine (Clozaril)". Australasian Psychiatry. 9 (4): 371. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1665.2001.0367a.x. ISSN 1039-8562. S2CID 73372315.

- Mossman D, Lehrer DS (December 2000). "Conventional and atypical antipsychotics and the evolving standard of care". Psychiatric Services. 51 (12): 1528–1535. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.12.1528. PMID 11097649.

- Pompili M, Lester D, Dominici G, Longo L, Marconi G, Forte A, et al. (May 2013). "Indications for electroconvulsive treatment in schizophrenia: a systematic review". Schizophrenia Research. 146 (1–3): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2022.09.021. PMID 23499244. S2CID 252276294.

- Li XB, Tang YL, Wang CY, de Leon J (May 2015). "Clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: a systematic review". Bipolar Disorders. 17 (3): 235–247. doi:10.1111/bdi.12272. PMID 25346322. S2CID 22689570.

- Goodwin GM (June 2009). "Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition--recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (4): 346–388. doi:10.1177/0269881109102919. PMID 19329543. S2CID 27827654.

- Bastiampillai T, Gupta A, Allison S, Chan SK (June 2016). "NICE guidance: why not clozapine for treatment-refractory bipolar disorder?". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 3 (6): 502–503. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30081-5. PMID 27262046.

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, et al. (March 2018). "Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder". Bipolar Disorders. 20 (2): 97–170. doi:10.1111/bdi.12609. PMC 5947163. PMID 29536616.

- Lähteenvuo M, Paljärvi T, Tanskanen A, Taipale H, Tiihonen J (October 2023). "Real-world effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for bipolar disorder: register-based national cohort study". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 223 (4): 456–464. doi:10.1192/bjp.2023.75. PMC 10866673. PMID 37395140.

- Gartlehner G, Crotty K, Kennedy S, Edlund MJ, Ali R, Siddiqui M, et al. (October 2021). "Pharmacological Treatments for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". CNS Drugs. 35 (10): 1053–1067. doi:10.26226/morressier.59d4913bd462b8029238a351. PMC 8478737. PMID 34495494.

- Beri A, Boydell J (May 2014). "Clozapine in borderline personality disorder: a review of the evidence". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 26 (2): 139–144. PMID 24812651.

- Frogley C, Anagnostakis K, Mitchell S, Mason F, Taylor D, Dickens G, et al. (May 2013). "A case series of clozapine for borderline personality disorder". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 25 (2): 125–134. PMID 23638443.

- Dickens GL, Frogley C, Mason F, Anagnostakis K, Picchioni MM (7 October 2016). "Experiences of women in secure care who have been prescribed clozapine for borderline personality disorder". Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 3 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s40479-016-0049-x. PMC 5055694. PMID 27761261.

- Rohde C, Polcwiartek C, Correll CU, Nielsen J (December 2018). "Real-World Effectiveness of Clozapine for Borderline Personality Disorder: Results From a 2-Year Mirror-Image Study". Journal of Personality Disorders. 32 (6): 823–837. doi:10.1521/pedi_2017_31_328. PMID 29120277. S2CID 26203378.

- Stoffers-Winterling J, Storebø OJ, Lieb K (June 2020). "Pharmacotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: an Update of Published, Unpublished and Ongoing Studies". Current Psychiatry Reports. 22 (8): 37. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01164-1. PMC 7275094. PMID 32504127.

- "NIHR Funding and Awards Search Website". fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Flanagan RJ, Lally J, Gee S, Lyon R, Every-Palmer S (October 2020). "Clozapine in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia: a practical guide for healthcare professionals". British Medical Bulletin. 135 (1): 73–89. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldaa024. PMC 7585831. PMID 32885238.

- ^ Beck K, McCutcheon R, Bloomfield MA, Gaughran F, Reis Marques T, MacCabe J, et al. (December 2014). "The practical management of refractory schizophrenia--the Maudsley Treatment REview and Assessment Team service approach". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 130 (6): 427–438. doi:10.1111/acps.12327. PMID 25201058. S2CID 36409113.

- "Clozaril 25 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Taylor D, Barnes TR, Young AH (2019). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry (13th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-44260-8. OCLC 1029071684.

- Wagner E, Kane JM, Correll CU, Howes O, Siskind D, Honer WG, et al. (December 2020). "Clozapine Combination and Augmentation Strategies in Patients With Schizophrenia -Recommendations From an International Expert Survey Among the Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (6): 1459–1470. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa060. PMC 7846085. PMID 32421188.

- Taylor D, Mace S, Mir S, Kerwin R (January 2000). "A prescription survey of the use of atypical antipsychotics for hospital inpatients in the United Kingdom". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 4 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1080/13651500052048749. PMID 24927311. S2CID 25337120.

- Sharma A (October 2018). "Maintenance doses for clozapine: past and present". BJPsych Bulletin. 42 (5): 217. doi:10.1192/bjb.2018.64. PMC 6189983. PMID 30345070.

- Pardiñas AF, Kappel DB, Roberts M, Tipple F, Shitomi-Jones LM, King A, et al. (March 2023). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of clozapine in an ancestrally diverse sample: a longitudinal analysis and genome-wide association study using UK clinical monitoring data". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 10 (3): 209–219. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(23)00002-0. PMC 10824469. PMID 36804072.

- Suzuki T, Remington G, Arenovich T, Uchida H, Agid O, Graff-Guerrero A, et al. (October 2011). "Time course of improvement with antipsychotic medication in treatment-resistant schizophrenia". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 199 (4): 275–280. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083907. PMID 22187729. S2CID 2382648.

- Kapur S, Arenovich T, Agid O, Zipursky R, Lindborg S, Jones B (May 2005). "Evidence for onset of antipsychotic effects within the first 24 hours of treatment". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (5): 939–946. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.939. PMID 15863796.

- Remington G (2010). "Augmenting Clozapine Response in Treatment-Resistant Schizophreni a". Therapy-Resistant Schizophrenia. Advances in Biological Psychiatry. Vol. 26. Basel: KARGER. pp. 129–151. doi:10.1159/000319813 (inactive 11 November 2024). ISBN 978-3-8055-9511-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Schulte P (2003). "What is an adequate trial with clozapine?: therapeutic drug monitoring and time to response in treatment-refractory schizophrenia". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 42 (7): 607–618. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342070-00001. PMID 12844323. S2CID 25525638.

- Conley RR, Carpenter WT, Tamminga CA (September 1997). "Time to clozapine response in a standardized trial". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 154 (9): 1243–1247. doi:10.1176/ajp.154.9.1243. PMID 9286183.

- Mistry H, Osborn D (July 2011). "Underuse of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 17 (4): 250–255. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.110.008128. ISSN 1355-5146.

- Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, Huang C, Olfson M (February 2014). "Geographic and clinical variation in clozapine use in the United States". Psychiatric Services. 65 (2): 186–192. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300180. PMID 24233347.

- Downs J, Zinkler M (October 2007). "Clozapine: national review of postcode prescribing". Psychiatric Bulletin. 31 (10): 384–387. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.106.013144. ISSN 0955-6036.

- Purcell H, Lewis S (November 2000). "Postcode prescribing in psychiatry". Psychiatric Bulletin. 24 (11): 420–422. doi:10.1192/pb.24.11.420. ISSN 0955-6036.

- Hayhurst KP, Brown P, Lewis SW (April 2003). "Postcode prescribing for schizophrenia". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 182 (4): 281–283. doi:10.1192/bjp.182.4.281. PMID 12668398.

- Nielsen J, Røge R, Schjerning O, Sørensen HJ, Taylor D (November 2012). "Geographical and temporal variations in clozapine prescription for schizophrenia". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 22 (11): 818–824. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.03.003. PMID 22503785. S2CID 40842497.

- Latimer E, Wynant W, Clark R, Malla A, Moodie E, Tamblyn R, et al. (April 2013). "Underprescribing of clozapine and unexplained variation in use across hospitals and regions in the Canadian province of Québec". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 7 (1): 33–41. doi:10.3371/csrp.lawy.012513. PMID 23367500.

- Whiskey E, Barnard A, Oloyede E, Dzahini O, Taylor DM, Shergill SS (April 2021). "An evaluation of the variation and underuse of clozapine in the United Kingdom" (PDF). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 143 (4): 339–347. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3716864. PMID 33501659. S2CID 235854803.

- Kelly DL, Kreyenbuhl J, Dixon L, Love RC, Medoff D, Conley RR (September 2007). "Clozapine underutilization and discontinuation in African Americans due to leucopenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (5): 1221–1224. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl068. PMC 2632351. PMID 17170061.

- ^ Mallinger JB, Fisher SG, Brown T, Lamberti JS (January 2006). "Racial disparities in the use of second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia". Psychiatric Services. 57 (1): 133–136. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.133. PMID 16399976.

- ^ Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Valenstein M, Blow FC (October 2003). "Racial disparity in the use of atypical antipsychotic medications among veterans". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (10): 1817–1822. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1817. PMID 14514496.

- Kelly DL, Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Medoff D, Lehman AF, Love RC, et al. (September 2006). "Clozapine utilization and outcomes by race in a public mental health system: 1994-2000". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (9): 1404–1411. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0911. PMID 17017827.

- Whiskey E, Olofinjana O, Taylor D (June 2011). "The importance of the recognition of benign ethnic neutropenia in black patients during treatment with clozapine: case reports and database study". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (6): 842–845. doi:10.1177/0269881110364267. PMID 20305043. S2CID 28714732.

- Cirulli G (October 2005). "Clozapine prescribing in adolescent psychiatry: survey of prescribing practice in in-patient units". Psychiatric Bulletin. 29 (10): 377–380. doi:10.1192/pb.29.10.377.

- Nielsen J, Dahm M, Lublin H, Taylor D (July 2010). "Psychiatrists' attitude towards and knowledge of clozapine treatment". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (7): 965–971. doi:10.1177/0269881108100320. PMID 19164499. S2CID 34614417.

- Hodge K, Jespersen S (February 2008). "Side-effects and treatment with clozapine: a comparison between the views of consumers and their clinicians". International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 17 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00506.x. PMID 18211398.

- Angermeyer MC, Löffler W, Müller P, Schulze B, Priebe S (April 2001). "Patients' and relatives' assessment of clozapine treatment". Psychological Medicine. 31 (3): 509–517. doi:10.1017/S0033291701003749. PMID 11305859. S2CID 20487762.

- Kelly D, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan R, Malhotra A (April 2007). "Why Not Clozapine?". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 1 (1): 92–95. doi:10.3371/csrp.1.1.8.

- Downs J, Zinkler M (October 2007). "Clozapine: national review of postcode prescribing". Psychiatric Bulletin. 31 (10): 384–387. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.106.013144. ISSN 0955-6036.

- Taylor DM, Young C, Paton C (January 2003). "Prior antipsychotic prescribing in patients currently receiving clozapine: a case note review". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (1): 30–34. doi:10.4088/jcp.v64n0107. PMID 12590620.

- Fayek M, Flowers C, Signorelli D, Simpson G (November 2003). "Psychopharmacology: underuse of evidence-based treatments in psychiatry". Psychiatric Services. 54 (11): 1453–4, 1456. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1453. PMID 14600298.

- Bachmann CJ, Aagaard L, Bernardo M, Brandt L, Cartabia M, Clavenna A, et al. (July 2017). "International trends in clozapine use: a study in 17 countries" (PDF). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 136 (1): 37–51. doi:10.1111/acps.12742. PMID 28502099.

- Pearl R. "Why Health Care Is Different If You're Black, Latino Or Poor". Forbes. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- "Racism in healthcare: Statistics and examples". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 17 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- Bulatao RA, Anderson NB, et al. (National Research Council (US) Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life) (2004). Stress. National Academies Press (US).

- Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S (October 2019). "Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations". Science. 366 (6464): 447–453. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..447O. doi:10.1126/science.aax2342. PMID 31649194. S2CID 204881868.

- Kelly DL, Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Medoff D, Lehman AF, Love RC, et al. (September 2006). "Clozapine utilization and outcomes by race in a public mental health system: 1994-2000". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (9): 1404–1411. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0911. PMID 17017827.

- Atallah-Yunes SA, Ready A, Newburger PE (September 2019). "Benign ethnic neutropenia". Blood Reviews. 37: 100586. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2019.06.003. PMC 6702066. PMID 31255364.

- Haddy TB, Rana SR, Castro O (January 1999). "Benign ethnic neutropenia: what is a normal absolute neutrophil count?". The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 133 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1053/lc.1999.v133.a94931. PMID 10385477.

- Rajagopal S (September 2005). "Clozapine, agranulocytosis, and benign ethnic neutropenia". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 81 (959): 545–546. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.031161. PMC 1743348. PMID 16143678.

- Reich D, Nalls MA, Kao WH, Akylbekova EL, Tandon A, Patterson N, et al. (January 2009). "Reduced neutrophil count in people of African descent is due to a regulatory variant in the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines gene". PLOS Genetics. 5 (1): e1000360. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000360. PMC 2628742. PMID 19180233.

- Silva E (28 August 2024). "Childhood onset violence and early onset schizophrenia. A molecular diagnosis of 15q13.2-13.3 duplication syndrome and the effects on insight and engagement". The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 35 (6): 984–995. doi:10.1080/14789949.2024.2396348. ISSN 1478-9949.