Pharmaceutical compound

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˌsiːtəlˌsælɪˈsɪlɪk/ |

| Trade names | Bayer Aspirin, others |

| Other names |

|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682878 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, rectal |

| Drug class | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80–100% |

| Protein binding | 80–90% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C19 and possibly CYP3A), some is also hydrolysed to salicylate in the gut wall. |

| Elimination half-life | Dose-dependent; 2–3 h for low doses (100 mg or less), 15–30 h for larger doses. |

| Excretion | Urine (80–100%), sweat, saliva, feces |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.059 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

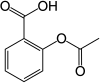

| Formula | C9H8O4 |

| Molar mass | 180.159 g·mol |

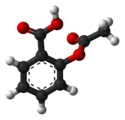

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.40 g/cm |

| Melting point | 135 °C (275 °F) |

| Boiling point | 140 °C (284 °F) (decomposes) |

| Solubility in water | 3 g/L |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Aspirin is the genericized trademark for acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions that aspirin is used to treat include Kawasaki disease, pericarditis, and rheumatic fever.

Aspirin is also used long-term to help prevent further heart attacks, ischaemic strokes, and blood clots in people at high risk. For pain or fever, effects typically begin within 30 minutes. Aspirin works similarly to other NSAIDs but also suppresses the normal functioning of platelets.

One common adverse effect is an upset stomach. More significant side effects include stomach ulcers, stomach bleeding, and worsening asthma. Bleeding risk is greater among those who are older, drink alcohol, take other NSAIDs, or are on other blood thinners. Aspirin is not recommended in the last part of pregnancy. It is not generally recommended in children with infections because of the risk of Reye syndrome. High doses may result in ringing in the ears.

A precursor to aspirin found in the bark of the willow tree (genus Salix) has been used for its health effects for at least 2,400 years. In 1853, chemist Charles Frédéric Gerhardt treated the medicine sodium salicylate with acetyl chloride to produce acetylsalicylic acid for the first time. Over the next 50 years, other chemists, mostly of the German company Bayer, established the chemical structure and devised more efficient production methods. Felix Hoffmann (or Arthur Eichengrün) of Bayer was the first to produce acetylsalicylic acid in a pure, stable form in 1897. By 1899, Bayer had dubbed this drug Aspirin and was selling it globally.

Aspirin is available without medical prescription as a proprietary or generic medication in most jurisdictions. It is one of the most widely used medications globally, with an estimated 40,000 tonnes (44,000 tons) (50 to 120 billion pills) consumed each year, and is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. In 2022, it was the 36th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 16 million prescriptions.

Brand vs. generic name

In 1897, scientists at the Bayer company began studying acetylsalicylic acid as a less-irritating replacement medication for common salicylate medicines. By 1899, Bayer had named it "Aspirin" and was selling it around the world.

Aspirin's popularity grew over the first half of the 20th century, leading to competition between many brands and formulations. The word Aspirin was Bayer's brand name; however, its rights to the trademark were lost or sold in many countries. The name is ultimately a blend of the prefix a(cetyl) + spir Spiraea, the meadowsweet plant genus from which the acetylsalicylic acid was originally derived at Bayer + -in, the common chemical suffix.

Chemical properties

Aspirin decomposes rapidly in solutions of ammonium acetate or the acetates, carbonates, citrates, or hydroxides of the alkali metals. It is stable in dry air, but gradually hydrolyses in contact with moisture to acetic and salicylic acids. In solution with alkalis, the hydrolysis proceeds rapidly and the clear solutions formed may consist entirely of acetate and salicylate.

Like flour mills, factories producing aspirin tablets must control the amount of the powder that becomes airborne inside the building, because the powder-air mixture can be explosive. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit in the United States of 5 mg/m (time-weighted average). In 1989, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) set a legal permissible exposure limit for aspirin of 5 mg/m, but this was vacated by the AFL-CIO v. OSHA decision in 1993.

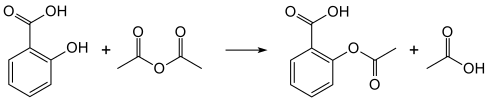

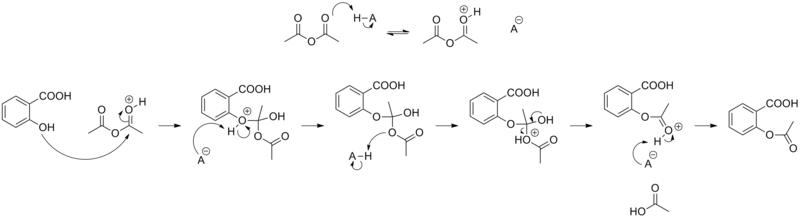

Synthesis

The synthesis of aspirin is classified as an esterification reaction. Salicylic acid is treated with acetic anhydride, an acid derivative, causing a chemical reaction that turns salicylic acid's hydroxyl group into an ester group (R-OH → R-OCOCH3). This process yields aspirin and acetic acid, which is considered a byproduct of this reaction. Small amounts of sulfuric acid (and occasionally phosphoric acid) are almost always used as a catalyst. This method is commonly demonstrated in undergraduate teaching labs.

Reaction between acetic acid and salicylic acid can also form aspirin but this esterification reaction is reversible and the presence of water can lead to hydrolysis of the aspirin. So, an anhydrous reagent is preferred.

- Reaction mechanism

Formulations containing high concentrations of aspirin often smell like vinegar because aspirin can decompose through hydrolysis in moist conditions, yielding salicylic and acetic acids.

Physical properties

Aspirin, an acetyl derivative of salicylic acid, is a white, crystalline, weakly acidic substance that melts at 136 °C (277 °F), and decomposes around 140 °C (284 °F). Its acid dissociation constant (pKa) is 3.5 at 25 °C (77 °F).

Polymorphism

Polymorphism, or the ability of a substance to form more than one crystal structure, is important in the development of pharmaceutical ingredients. Many drugs receive regulatory approval for only a single crystal form or polymorph.

Until 2005, there was only one proven polymorph of aspirin (Form I), though the existence of another polymorph was debated since the 1960s, and one report from 1981 reported that when crystallized in the presence of aspirin anhydride, the diffractogram of aspirin has weak additional peaks. Though at the time it was dismissed as mere impurity, it was, in retrospect, Form II aspirin.

Form II was reported in 2005, found after attempted co-crystallization of aspirin and levetiracetam from hot acetonitrile.

In form I, pairs of aspirin molecules form centrosymmetric dimers through the acetyl groups with the (acidic) methyl proton to carbonyl hydrogen bonds. In form II, each aspirin molecule forms the same hydrogen bonds, but with two neighbouring molecules instead of one. With respect to the hydrogen bonds formed by the carboxylic acid groups, both polymorphs form identical dimer structures. The aspirin polymorphs contain identical 2-dimensional sections and are therefore more precisely described as polytypes.

Pure Form II aspirin could be prepared by seeding the batch with aspirin anhydrate in 15% weight.

Form III was reported in 2015 by compressing form I above 2 GPa, but it reverts back to Form I when pressure is removed. Form IV was reported in 2017. It is stable at ambient conditions.

Mechanism of action

Main article: Mechanism of action of aspirinDiscovery of the mechanism

In 1971, British pharmacologist John Robert Vane, then employed by the Royal College of Surgeons in London, showed aspirin suppressed the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes. For this discovery he was awarded the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, jointly with Sune Bergström and Bengt Ingemar Samuelsson.

Prostaglandins and thromboxanes

Aspirin's ability to suppress the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes is due to its irreversible inactivation of the cyclooxygenase (COX; officially known as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase, PTGS) enzyme required for prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis. Aspirin acts as an acetylating agent where an acetyl group is covalently attached to a serine residue in the active site of the COX enzyme (Suicide inhibition). This makes aspirin different from other NSAIDs (such as diclofenac and ibuprofen), which are reversible inhibitors.

Low-dose aspirin use irreversibly blocks the formation of thromboxane A2 in platelets, producing an inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation during the lifetime of the affected platelet (8–9 days). This antithrombotic property makes aspirin useful for reducing the incidence of heart attacks in people who have had a heart attack, unstable angina, ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. 40 mg of aspirin a day is able to inhibit a large proportion of maximum thromboxane A2 release provoked acutely, with the prostaglandin I2 synthesis being little affected; however, higher doses of aspirin are required to attain further inhibition.

Prostaglandins, local hormones produced in the body, have diverse effects, including the transmission of pain information to the brain, modulation of the hypothalamic thermostat, and inflammation. Thromboxanes are responsible for the aggregation of platelets that form blood clots. Heart attacks are caused primarily by blood clots, and low doses of aspirin are seen as an effective medical intervention to prevent a second acute myocardial infarction.

COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition

At least two different types of cyclooxygenases, COX-1 and COX-2, are acted on by aspirin. Aspirin irreversibly inhibits COX-1 and modifies the enzymatic activity of COX-2. COX-2 normally produces prostanoids, most of which are proinflammatory. Aspirin-modified COX-2 (aka prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 or PTGS2) produces epi-lipoxins, most of which are anti-inflammatory. Newer NSAID drugs, COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs), have been developed to inhibit only COX-2, with the intent to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects.

Several COX-2 inhibitors, such as rofecoxib (Vioxx), have been withdrawn from the market, after evidence emerged that COX-2 inhibitors increase the risk of heart attack and stroke. Endothelial cells lining the microvasculature in the body are proposed to express COX-2, and, by selectively inhibiting COX-2, prostaglandin production (specifically, PGI2; prostacyclin) is downregulated with respect to thromboxane levels, as COX-1 in platelets is unaffected. Thus, the protective anticoagulative effect of PGI2 is removed, increasing the risk of thrombus and associated heart attacks and other circulatory problems. Since platelets have no DNA, they are unable to synthesize new COX-1 once aspirin has irreversibly inhibited the enzyme, an important difference as compared with reversible inhibitors.

Furthermore, aspirin, while inhibiting the ability of COX-2 to form pro-inflammatory products such as the prostaglandins, converts this enzyme's activity from a prostaglandin-forming cyclooxygenase to a lipoxygenase-like enzyme: aspirin-treated COX-2 metabolizes a variety of polyunsaturated fatty acids to hydroperoxy products which are then further metabolized to specialized proresolving mediators such as the aspirin-triggered lipoxins(15-epilipoxin-A4/B4), aspirin-triggered resolvins, and aspirin-triggered maresins. These mediators possess potent anti-inflammatory activity. It is proposed that this aspirin-triggered transition of COX-2 from cyclooxygenase to lipoxygenase activity and the consequential formation of specialized proresolving mediators contributes to the anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin.

Additional mechanisms

Aspirin has been shown to have at least three additional modes of action. It uncouples oxidative phosphorylation in cartilaginous (and hepatic) mitochondria, by diffusing from the inner membrane space as a proton carrier back into the mitochondrial matrix, where it ionizes once again to release protons. Aspirin buffers and transports the protons. When high doses are given, it may actually cause fever, owing to the heat released from the electron transport chain, as opposed to the antipyretic action of aspirin seen with lower doses. In addition, aspirin induces the formation of NO-radicals in the body, which have been shown in mice to have an independent mechanism of reducing inflammation. This reduced leukocyte adhesion is an important step in the immune response to infection; however, evidence is insufficient to show aspirin helps to fight infection. More recent data also suggest salicylic acid and its derivatives modulate signalling through NF-κB. NF-κB, a transcription factor complex, plays a central role in many biological processes, including inflammation.

Aspirin is readily broken down in the body to salicylic acid, which itself has anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic effects. In 2012, salicylic acid was found to activate AMP-activated protein kinase, which has been suggested as a possible explanation for some of the effects of both salicylic acid and aspirin. The acetyl portion of the aspirin molecule has its own targets. Acetylation of cellular proteins is a well-established phenomenon in the regulation of protein function at the post-translational level. Aspirin is able to acetylate several other targets in addition to COX isoenzymes. These acetylation reactions may explain many hitherto unexplained effects of aspirin.

Formulations

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2023) |

Aspirin is produced in many formulations, with some differences in effect. In particular, aspirin can cause gastrointestinal bleeding, and formulations are sought which deliver the benefits of aspirin while mitigating harmful bleeding. Formulations may be combined (e.g., buffered + vitamin C).

- Tablets, typically of about 75–100 mg and 300–320 mg of immediate-release aspirin (IR-ASA).

- Dispersible tablets.

- Enteric-coated tablets.

- Buffered formulations containing aspirin with one of many buffering agents.

- Formulations of aspirin with vitamin C (ASA-VitC)

- A phospholipid-aspirin complex liquid formulation, PL-ASA. As of 2023 the phospholipid coating was being trialled to determine if it caused less gastrointestinal damage.

Pharmacokinetics

Acetylsalicylic acid is a weak acid, and very little of it is ionized in the stomach after oral administration. Acetylsalicylic acid is quickly absorbed through the cell membrane in the acidic conditions of the stomach. The increased pH and larger surface area of the small intestine causes aspirin to be absorbed more slowly there, as more of it is ionized. Owing to the formation of concretions, aspirin is absorbed much more slowly during overdose, and plasma concentrations can continue to rise for up to 24 hours after ingestion.

About 50–80% of salicylate in the blood is bound to human serum albumin, while the rest remains in the active, ionized state; protein binding is concentration-dependent. Saturation of binding sites leads to more free salicylate and increased toxicity. The volume of distribution is 0.1–0.2 L/kg. Acidosis increases the volume of distribution because of enhancement of tissue penetration of salicylates.

As much as 80% of therapeutic doses of salicylic acid is metabolized in the liver. Conjugation with glycine forms salicyluric acid, and with glucuronic acid to form two different glucuronide esters. The conjugate with the acetyl group intact is referred to as the acyl glucuronide; the deacetylated conjugate is the phenolic glucuronide. These metabolic pathways have only a limited capacity. Small amounts of salicylic acid are also hydroxylated to gentisic acid. With large salicylate doses, the kinetics switch from first-order to zero-order, as metabolic pathways become saturated and renal excretion becomes increasingly important.

Salicylates are excreted mainly by the kidneys as salicyluric acid (75%), free salicylic acid (10%), salicylic phenol (10%), and acyl glucuronides (5%), gentisic acid (< 1%), and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid. When small doses (less than 250 mg in an adult) are ingested, all pathways proceed by first-order kinetics, with an elimination half-life of about 2.0 h to 4.5 h. When higher doses of salicylate are ingested (more than 4 g), the half-life becomes much longer (15 h to 30 h), because the biotransformation pathways concerned with the formation of salicyluric acid and salicyl phenolic glucuronide become saturated. Renal excretion of salicylic acid becomes increasingly important as the metabolic pathways become saturated, because it is extremely sensitive to changes in urinary pH. A 10- to 20-fold increase in renal clearance occurs when urine pH is increased from 5 to 8. The use of urinary alkalinization exploits this particular aspect of salicylate elimination. It was found that short-term aspirin use in therapeutic doses might precipitate reversible acute kidney injury when the patient was ill with glomerulonephritis or cirrhosis. Aspirin for some patients with chronic kidney disease and some children with congestive heart failure was contraindicated.

History

Main article: History of aspirin

Medicines made from willow and other salicylate-rich plants appear in clay tablets from ancient Sumer as well as the Ebers Papyrus from ancient Egypt. Hippocrates referred to the use of salicylic tea to reduce fevers around 400 BC, and willow bark preparations were part of the pharmacopoeia of Western medicine in classical antiquity and the Middle Ages. Willow bark extract became recognized for its specific effects on fever, pain, and inflammation in the mid-eighteenth century after the Rev Edward Stone of Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, noticed that the bitter taste of willow bark resembled the taste of the bark of the cinchona tree, known as "Peruvian bark", which was used successfully in Peru to treat a variety of ailments. Stone experimented with preparations of powdered willow bark on people in Chipping Norton for five years and found it to be as effective as Peruvian bark and a cheaper domestic version. In 1763 he sent a report of his findings to the Royal Society in London. By the nineteenth century, pharmacists were experimenting with and prescribing a variety of chemicals related to salicylic acid, the active component of willow extract.

In 1853, chemist Charles Frédéric Gerhardt treated sodium salicylate with acetyl chloride to produce acetylsalicylic acid for the first time; in the second half of the 19th century, other academic chemists established the compound's chemical structure and devised more efficient methods of synthesis. In 1897, scientists at the drug and dye firm Bayer began investigating acetylsalicylic acid as a less-irritating replacement for standard common salicylate medicines, and identified a new way to synthesize it. That year, Felix Hoffmann (or Arthur Eichengrün) of Bayer was the first to produce acetylsalicylic acid in a pure, stable form. By 1899, Bayer had dubbed this drug Aspirin and was selling it globally. The word Aspirin was Bayer's brand name, rather than the generic name of the drug; however, Bayer's rights to the trademark were lost or sold in many countries. Aspirin's popularity grew over the first half of the 20th century leading to fierce competition with the proliferation of aspirin brands and products.

Aspirin's popularity declined after the development of acetaminophen/paracetamol in 1956 and ibuprofen in 1962. In the 1960s and 1970s, John Vane and others discovered the basic mechanism of aspirin's effects, while clinical trials and other studies from the 1960s to the 1980s established aspirin's efficacy as an anti-clotting agent that reduces the risk of clotting diseases. The initial large studies on the use of low-dose aspirin to prevent heart attacks that were published in the 1970s and 1980s helped spur reform in clinical research ethics and guidelines for human subject research and US federal law, and are often cited as examples of clinical trials that included only men, but from which people drew general conclusions that did not hold true for women.

Aspirin sales revived considerably in the last decades of the 20th century, and remain strong in the 21st century with widespread use as a preventive treatment for heart attacks and strokes.

Trademark

In Canada and many other countries, "Aspirin" remains a trademark, so generic aspirin is sold as "ASA" (acetylsalicylic acid).

In Canada and many other countries, "Aspirin" remains a trademark, so generic aspirin is sold as "ASA" (acetylsalicylic acid). In the US., "aspirin" is a generic name.

In the US., "aspirin" is a generic name.

Bayer lost its trademark for Aspirin in the United States and some other countries in actions taken between 1918 and 1921 because it had failed to use the name for its own product correctly and had for years allowed the use of "Aspirin" by other manufacturers without defending the intellectual property rights. Today, aspirin is a generic trademark in many countries. Aspirin, with a capital "A", remains a registered trademark of Bayer in Germany, Canada, Mexico, and in over 80 other countries, for acetylsalicylic acid in all markets, but using different packaging and physical aspects for each.

Compendial status

Medical use

Aspirin is used in the treatment of a number of conditions, including fever, pain, rheumatic fever, and inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, pericarditis, and Kawasaki disease. Lower doses of aspirin have also been shown to reduce the risk of death from a heart attack, or the risk of stroke in people who are at high risk or who have cardiovascular disease, but not in elderly people who are otherwise healthy. There is evidence that aspirin is effective at preventing colorectal cancer, though the mechanisms of this effect are unclear.

Pain

Aspirin is an effective analgesic for acute pain, although it is generally considered inferior to ibuprofen because aspirin is more likely to cause gastrointestinal bleeding. Aspirin is generally ineffective for those pains caused by muscle cramps, bloating, gastric distension, or acute skin irritation. As with other NSAIDs, combinations of aspirin and caffeine provide slightly greater pain relief than aspirin alone. Effervescent formulations of aspirin relieve pain faster than aspirin in tablets, which makes them useful for the treatment of migraines. Topical aspirin may be effective for treating some types of neuropathic pain.

Aspirin, either by itself or in a combined formulation, effectively treats certain types of a headache, but its efficacy may be questionable for others. Secondary headaches, meaning those caused by another disorder or trauma, should be promptly treated by a medical provider. Among primary headaches, the International Classification of Headache Disorders distinguishes between tension headache (the most common), migraine, and cluster headache. Aspirin or other over-the-counter analgesics are widely recognized as effective for the treatment of tension headaches. Aspirin, especially as a component of an aspirin/paracetamol/caffeine combination, is considered a first-line therapy in the treatment of migraine, and comparable to lower doses of sumatriptan. It is most effective at stopping migraines when they are first beginning.

Fever

Like its ability to control pain, aspirin's ability to control fever is due to its action on the prostaglandin system through its irreversible inhibition of COX. Although aspirin's use as an antipyretic in adults is well established, many medical societies and regulatory agencies, including the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Food and Drug Administration, strongly advise against using aspirin for the treatment of fever in children because of the risk of Reye's syndrome, a rare but often fatal illness associated with the use of aspirin or other salicylates in children during episodes of viral or bacterial infection. Because of the risk of Reye's syndrome in children, in 1986, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required labeling on all aspirin-containing medications advising against its use in children and teenagers.

Inflammation

Aspirin is used as an anti-inflammatory agent for both acute and long-term inflammation, as well as for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Heart attacks and strokes

Aspirin is an important part of the treatment of those who have had a heart attack. It is generally not recommended for routine use by people with no other health problems, including those over the age of 70.

The 2009 Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration published in Lancet evaluated the efficacy and safety of low dose aspirin in secondary prevention. In those with prior ischaemic stroke or acute myocardial infarction, daily low dose aspirin was associated with a 19% relative risk reduction of serious cardiovascular events (non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, or vascular death). This did come at the expense of a 0.19% absolute risk increase in gastrointestinal bleeding; however, the benefits outweigh the hazard risk in this case. Data from previous trials have suggested that weight-based dosing of aspirin has greater benefits in primary prevention of cardiovascular outcomes. However, more recent trials were not able to replicate similar outcomes using low dose aspirin in low body weight (<70 kg) in specific subset of population studied i.e. elderly and diabetic population, and more evidence is required to study the effect of high dose aspirin in high body weight (≥70 kg).

After percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs), such as the placement of a coronary artery stent, a U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality guideline recommends that aspirin be taken indefinitely. Frequently, aspirin is combined with an ADP receptor inhibitor, such as clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor to prevent blood clots. This is called dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). Duration of DAPT was advised in the United States and European Union guidelines after the CURE and PRODIGY studies. In 2020, the systematic review and network meta-analysis from Khan et al. showed promising benefits of short-term (< 6 months) DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitors in selected patients, as well as the benefits of extended-term (> 12 months) DAPT in high risk patients. In conclusion, the optimal duration of DAPT after PCIs should be personalized after outweighing each patient's risks of ischemic events and risks of bleeding events with consideration of multiple patient-related and procedure-related factors. Moreover, aspirin should be continued indefinitely after DAPT is complete.

The status of the use of aspirin for the primary prevention in cardiovascular disease is conflicting and inconsistent, with recent changes from previously recommending it widely decades ago, and that some referenced newer trials in clinical guidelines show less of benefit of adding aspirin alongside other anti-hypertensive and cholesterol lowering therapies. The ASCEND study demonstrated that in high-bleeding risk diabetics with no prior cardiovascular disease, there is no overall clinical benefit (12% decrease in risk of ischaemic events v/s 29% increase in GI bleeding) of low dose aspirin in preventing the serious vascular events over a period of 7.4 years. Similarly, the results of the ARRIVE study also showed no benefit of same dose of aspirin in reducing the time to first cardiovascular outcome in patients with moderate risk of cardiovascular disease over a period of five years. Aspirin has also been suggested as a component of a polypill for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Complicating the use of aspirin for prevention is the phenomenon of aspirin resistance. For people who are resistant, aspirin's efficacy is reduced. Some authors have suggested testing regimens to identify people who are resistant to aspirin.

As of April 2022, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) determined that there was a "small net benefit" for patients aged 40–59 with a 10% or greater 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, and "no net benefit" for patients aged over 60. Determining the net benefit was based on balancing the risk reduction of taking aspirin for heart attacks and ischaemic strokes, with the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and hemorrhagic strokes. Their recommendations state that age changes the risk of the medicine, with the magnitude of the benefit of aspirin coming from starting at a younger age, while the risk of bleeding, while small, increases with age, particular for adults over 60, and can be compounded by other risk factors such as diabetes and a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. As a result, the USPSTF suggests that "people ages 40 to 59 who are at higher risk for CVD should decide with their clinician whether to start taking aspirin; people 60 or older should not start taking aspirin to prevent a first heart attack or stroke." Primary prevention guidelines from September 2019 made by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association state they might consider aspirin for patients aged 40–69 with a higher risk of atherosclerotic CVD, without an increased bleeding risk, while stating they would not recommend aspirin for patients aged over 70 or adults of any age with an increased bleeding risk. They state a CVD risk estimation and a risk discussion should be done before starting on aspirin, while stating aspirin should be used "infrequently in the routine primary prevention of (atherosclerotic CVD) because of lack of net benefit". As of August 2021, the European Society of Cardiology made similar recommendations; considering aspirin specifically to patients aged less than 70 at high or very high CVD risk, without any clear contraindications, on a case-by-case basis considering both ischemic risk and bleeding risk.

Cancer prevention

Aspirin may reduce the overall risk of both getting cancer and dying from cancer. There is substantial evidence for lowering the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC), but aspirin must be taken for at least 10–20 years to see this benefit. It may also slightly reduce the risk of endometrial cancer and prostate cancer.

Some conclude the benefits are greater than the risks due to bleeding in those at average risk. Others are unclear if the benefits are greater than the risk. Given this uncertainty, the 2007 United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines on this topic recommended against the use of aspirin for prevention of CRC in people with average risk. Nine years later however, the USPSTF issued a grade B recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin (75 to 100 mg/day) "for the primary prevention of CVD and CRC in adults 50 to 59 years of age who have a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, are not at increased risk for bleeding, have a life expectancy of at least 10 years, and are willing to take low-dose aspirin daily for at least 10 years".

A meta-analysis through 2019 said that there was an association between taking aspirin and lower risk of cancer of the colorectum, esophagus, and stomach.

In 2021, the U.S. Preventive services Task Force raised questions about the use of aspirin in cancer prevention. It notes the results of the 2018 ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) Trial, in which the risk of cancer-related death was higher in the aspirin-treated group than in the placebo group.

Psychiatry

Bipolar disorder

Aspirin, along with several other agents with anti-inflammatory properties, has been repurposed as an add-on treatment for depressive episodes in subjects with bipolar disorder in light of the possible role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of severe mental disorders. A 2022 systematic review concluded that aspirin exposure reduced the risk of depression in a pooled cohort of three studies (HR 0.624, 95% CI: 0.0503, 1.198, P=0.033). However, further high-quality, longer-duration, double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to determine whether aspirin is an effective add-on treatment for bipolar depression. Thus, notwithstanding the biological rationale, the clinical perspectives of aspirin and anti-inflammatory agents in the treatment of bipolar depression remain uncertain.

Dementia

Although cohort and longitudinal studies have shown low-dose aspirin has a greater likelihood of reducing the incidence of dementia, numerous randomized controlled trials have not validated this.

Schizophrenia

Some researchers have speculated the anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin may be beneficial for schizophrenia. Small trials have been conducted but evidence remains lacking.

Other uses

Aspirin is a first-line treatment for the fever and joint-pain symptoms of acute rheumatic fever. The therapy often lasts for one to two weeks, and is rarely indicated for longer periods. After fever and pain have subsided, the aspirin is no longer necessary, since it does not decrease the incidence of heart complications and residual rheumatic heart disease. Naproxen has been shown to be as effective as aspirin and less toxic, but due to the limited clinical experience, naproxen is recommended only as a second-line treatment.

Along with rheumatic fever, Kawasaki disease remains one of the few indications for aspirin use in children in spite of a lack of high quality evidence for its effectiveness.

Low-dose aspirin supplementation has moderate benefits when used for prevention of pre-eclampsia. This benefit is greater when started in early pregnancy.

Aspirin has also demonstrated anti-tumoral effects, via inhibition of the PTTG1 gene, which is often overexpressed in tumors.

Resistance

See also: Drug toleranceFor some people, aspirin does not have as strong an effect on platelets as for others, an effect known as aspirin-resistance or insensitivity. One study has suggested women are more likely to be resistant than men, and a different, aggregate study of 2,930 people found 28% were resistant. A study in 100 Italian people found, of the apparent 31% aspirin-resistant subjects, only 5% were truly resistant, and the others were noncompliant. Another study of 400 healthy volunteers found no subjects who were truly resistant, but some had "pseudoresistance, reflecting delayed and reduced drug absorption".

Meta-analysis and systematic reviews have concluded that laboratory confirmed aspirin resistance confers increased rates of poorer outcomes in cardiovascular and neurovascular diseases. Although the majority of research conducted has surrounded cardiovascular and neurovascular, there is emerging research into the risk of aspirin resistance after orthopaedic surgery where aspirin is used for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Aspirin resistance in orthopaedic surgery, specifically after total hip and knee arthroplasties, is of interest as risk factors for aspirin resistance are also risk factors for venous thromboembolisms and osteoarthritis; the sequelae of requiring a total hip or knee arthroplasty. Some of these risk factors include obesity, advancing age, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and inflammatory diseases.

Dosages

Adult aspirin tablets are produced in standardised sizes, which vary slightly from country to country, for example 300 mg in Britain and 325 mg in the United States. Smaller doses are based on these standards, e.g., 75 mg and 81 mg tablets. The 81 mg tablets are commonly called "baby aspirin" or "baby-strength", because they were originally – but no longer – intended to be administered to infants and children. No medical significance occurs due to the slight difference in dosage between the 75 mg and the 81 mg tablets. The dose required for benefit appears to depend on a person's weight. For those weighing less than 70 kilograms (154 lb), low dose is effective for preventing cardiovascular disease; for patients above this weight, higher doses are required.

In general, for adults, doses are taken four times a day for fever or arthritis, with doses near the maximal daily dose used historically for the treatment of rheumatic fever. For the prevention of myocardial infarction (MI) in someone with documented or suspected coronary artery disease, much lower doses are taken once daily.

March 2009 recommendations from the USPSTF on the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease encourage men aged 45–79 and women aged 55–79 to use aspirin when the potential benefit of a reduction in MI for men or stroke for women outweighs the potential harm of an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The WHI study of postmenopausal women found that aspirin resulted in a 25% lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease and a 14% lower risk of death from any cause, though there was no significant difference between 81 mg and 325 mg aspirin doses. The 2021 ADAPTABLE study also showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events or major bleeding between 81 mg and 325 mg doses of aspirin in patients (both men and women) with established cardiovascular disease.

Low-dose aspirin use was also associated with a trend toward lower risk of cardiovascular events, and lower aspirin doses (75 or 81 mg/day) may optimize efficacy and safety for people requiring aspirin for long-term prevention.

In children with Kawasaki disease, aspirin is taken at dosages based on body weight, initially four times a day for up to two weeks and then at a lower dose once daily for a further six to eight weeks.

Adverse effects

In October 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the drug label to be updated for all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications to describe the risk of kidney problems in unborn babies that result in low amniotic fluid. They recommend avoiding NSAIDs in pregnant women at 20 weeks or later in pregnancy. One exception to the recommendation is the use of low-dose 81 mg aspirin at any point in pregnancy under the direction of a health care professional.

Contraindications

Aspirin should not be taken by people who are allergic to ibuprofen or naproxen, or who have salicylate intolerance or a more generalized drug intolerance to NSAIDs, and caution should be exercised in those with asthma or NSAID-precipitated bronchospasm. Owing to its effect on the stomach lining, manufacturers recommend people with peptic ulcers, mild diabetes, or gastritis seek medical advice before using aspirin. Even if none of these conditions is present, the risk of stomach bleeding is still increased when aspirin is taken with alcohol or warfarin. People with hemophilia or other bleeding tendencies should not take aspirin or other salicylates. Aspirin is known to cause hemolytic anemia in people who have the genetic disease glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, particularly in large doses and depending on the severity of the disease. Use of aspirin during dengue fever is not recommended owing to increased bleeding tendency. Aspirin taken at doses of ≤325 mg and ≤100 mg per day for ≥2 days can increase the odds of suffering a gout attack by 81% and 91% respectively. This effect may potentially be worsened by high purine diets, diuretics, and kidney disease, but is eliminated by the urate lowering drug allopurinol. Daily low dose aspirin does not appear to worsen kidney function. Aspirin may reduce cardiovascular risk in those without established cardiovascular disease in people with moderate CKD, without significantly increasing the risk of bleeding. Aspirin should not be given to children or adolescents under the age of 16 to control cold or influenza symptoms, as this has been linked with Reye's syndrome.

Gastrointestinal

Aspirin increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Enteric coating on aspirin may be used in manufacturing to prevent release of aspirin into the stomach to reduce gastric harm, but enteric coating does not reduce gastrointestinal bleeding risk. Enteric-coated aspirin may not be as effective at reducing blood clot risk. Combining aspirin with other NSAIDs has been shown to further increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Using aspirin in combination with clopidogrel or warfarin also increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Blockade of COX-1 by aspirin apparently results in the upregulation of COX-2 as part of a gastric defense. There is no clear evidence that simultaneous use of a COX-2 inhibitor with aspirin may increase the risk of gastrointestinal injury.

"Buffering" is an additional method used with the intent to mitigate gastrointestinal bleeding, such as by preventing aspirin from concentrating in the walls of the stomach, although the benefits of buffered aspirin are disputed. Almost any buffering agent used in antacids can be used; Bufferin, for example, uses magnesium oxide. Other preparations use calcium carbonate. Gas-forming agents in effervescent tablet and powder formulations can also double as a buffering agent, one example being sodium bicarbonate, used in Alka-Seltzer.

Taking vitamin C with aspirin has been investigated as a method of protecting the stomach lining. In trials vitamin C-releasing aspirin (ASA-VitC) or a buffered aspirin formulation containing vitamin C was found to cause less stomach damage than aspirin alone.

Retinal vein occlusion

It is a widespread habit among eye specialists (ophthalmologists) to prescribe aspirin as an add-on medication for patients with retinal vein occlusion (RVO), such as central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). The reason of this widespread use is the evidence of its proven effectiveness in major systemic venous thrombotic disorders, and it has been assumed that may be similarly beneficial in various types of retinal vein occlusion.

However, a large-scale investigation based on data of nearly 700 patients showed "that aspirin or other antiplatelet aggregating agents or anticoagulants adversely influence the visual outcome in patients with CRVO and hemi-CRVO, without any evidence of protective or beneficial effect". Several expert groups, including the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, recommended against the use of antithrombotic drugs (incl. aspirin) for patients with RVO.

Central effects

Large doses of salicylate, a metabolite of aspirin, cause temporary tinnitus (ringing in the ears) based on experiments in rats, via the action on arachidonic acid and NMDA receptors cascade.

Reye's syndrome

Main article: Reye's syndromeReye's syndrome, a rare but severe illness characterized by acute encephalopathy and fatty liver, can occur when children or adolescents are given aspirin for a fever or other illness or infection. From 1981 to 1997, 1207 cases of Reye's syndrome in people younger than 18 were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Of these, 93% reported being ill in the three weeks preceding the onset of Reye's syndrome, most commonly with a respiratory infection, chickenpox, or diarrhea. Salicylates were detectable in 81.9% of children for whom test results were reported. After the association between Reye's syndrome and aspirin was reported, and safety measures to prevent it (including a Surgeon General's warning, and changes to the labeling of aspirin-containing drugs) were implemented, aspirin taken by children declined considerably in the United States, as did the number of reported cases of Reye's syndrome; a similar decline was found in the United Kingdom after warnings against pediatric aspirin use were issued. The US Food and Drug Administration recommends aspirin (or aspirin-containing products) should not be given to anyone under the age of 12 who has a fever, and the UK National Health Service recommends children who are under 16 years of age should not take aspirin, unless it is on the advice of a doctor.

Skin

For a small number of people, taking aspirin can result in symptoms including hives, swelling, and headache. Aspirin can exacerbate symptoms among those with chronic hives, or create acute symptoms of hives. These responses can be due to allergic reactions to aspirin, or more often due to its effect of inhibiting the COX-1 enzyme. Skin reactions may also tie to systemic contraindications, seen with NSAID-precipitated bronchospasm, or those with atopy.

Aspirin and other NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, may delay the healing of skin wounds. Earlier findings from two small, low-quality trials suggested a benefit with aspirin (alongside compression therapy) on venous leg ulcer healing time and leg ulcer size, however larger, more recent studies of higher quality have been unable to corroborate these outcomes. As such, further research is required to clarify the role of aspirin in this context.

Other adverse effects

Aspirin can induce swelling of skin tissues in some people. In one study, angioedema appeared one to six hours after ingesting aspirin in some of the people. However, when the aspirin was taken alone, it did not cause angioedema in these people; the aspirin had been taken in combination with another NSAID-induced drug when angioedema appeared.

Aspirin causes an increased risk of cerebral microbleeds, having the appearance on MRI scans of 5 to 10 mm or smaller, hypointense (dark holes) patches.

A study of a group with a mean dosage of aspirin of 270 mg per day estimated an average absolute risk increase in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) of 12 events per 10,000 persons. In comparison, the estimated absolute risk reduction in myocardial infarction was 137 events per 10,000 persons, and a reduction of 39 events per 10,000 persons in ischemic stroke. In cases where ICH already has occurred, aspirin use results in higher mortality, with a dose of about 250 mg per day resulting in a relative risk of death within three months after the ICH around 2.5 (95% confidence interval 1.3 to 4.6).

Aspirin and other NSAIDs can cause abnormally high blood levels of potassium by inducing a hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism state via inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis; however, these agents do not typically cause hyperkalemia by themselves in the setting of normal renal function and euvolemic state.

Use of low-dose aspirin before a surgical procedure has been associated with an increased risk of bleeding events in some patients, however, ceasing aspirin prior to surgery has also been associated with an increase in major adverse cardiac events. An analysis of multiple studies found a three-fold increase in adverse events such as myocardial infarction in patients who ceased aspirin prior to surgery. The analysis found that the risk is dependent on the type of surgery being performed and the patient indication for aspirin use.

On 9 July 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) toughened warnings of increased heart attack and stroke risk associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Aspirin is an NSAID but is not affected by the new warnings.

Overdose

Main article: Aspirin poisoningAspirin overdose can be acute or chronic. In acute poisoning, a single large dose is taken; in chronic poisoning, higher than normal doses are taken over a period of time. Acute overdose has a mortality rate of 2%. Chronic overdose is more commonly lethal, with a mortality rate of 25%; chronic overdose may be especially severe in children. Toxicity is managed with a number of potential treatments, including activated charcoal, intravenous dextrose and normal saline, sodium bicarbonate, and dialysis. The diagnosis of poisoning usually involves measurement of plasma salicylate, the active metabolite of aspirin, by automated spectrophotometric methods. Plasma salicylate levels in general range from 30 to 100 mg/L after usual therapeutic doses, 50–300 mg/L in people taking high doses and 700–1400 mg/L following acute overdose. Salicylate is also produced as a result of exposure to bismuth subsalicylate, methyl salicylate, and sodium salicylate.

Interactions

Aspirin is known to interact with other drugs. For example, acetazolamide and ammonium chloride are known to enhance the intoxicating effect of salicylates, and alcohol also increases the gastrointestinal bleeding associated with these types of drugs. Aspirin is known to displace a number of drugs from protein-binding sites in the blood, including the antidiabetic drugs tolbutamide and chlorpropamide, warfarin, methotrexate, phenytoin, probenecid, valproic acid (as well as interfering with beta oxidation, an important part of valproate metabolism), and other NSAIDs. Corticosteroids may also reduce the concentration of aspirin. Other NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and naproxen, may reduce the antiplatelet effect of aspirin. Although limited evidence suggests this may not result in a reduced cardioprotective effect of aspirin. Analgesic doses of aspirin decrease sodium loss induced by spironolactone in the urine, however this does not reduce the antihypertensive effects of spironolactone. Furthermore, antiplatelet doses of aspirin are deemed too small to produce an interaction with spironolactone. Aspirin is known to compete with penicillin G for renal tubular secretion. Aspirin may also inhibit the absorption of vitamin C.

Research

The ISIS-2 trial demonstrated that aspirin at doses of 160 mg daily for one month, decreased the mortality by 21% of participants with a suspected myocardial infarction in the first five weeks. A single daily dose of 324 mg of aspirin for 12 weeks has a highly protective effect against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina.

Bipolar disorder

Aspirin has been repurposed as an add-on treatment for depressive episodes in subjects with bipolar disorder. However, meta-analytic evidence is based on very few studies and does not suggest any efficacy of aspirin in the treatment of bipolar depression. Thus, notwithstanding the biological rationale, the clinical perspectives of aspirin and anti-inflammatory agents in the treatment of bipolar depression remain uncertain.

Infectious diseases

Several studies investigated the anti-infective properties of aspirin for bacterial, viral and parasitic infections. Aspirin was demonstrated to limit platelet activation induced by Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis and to reduce streptococcal adhesion to heart valves. In patients with tuberculous meningitis, the addition of aspirin reduced the risk of new cerebral infarction . A role of aspirin on bacterial and fungal biofilm is also being supported by growing evidence.

Cancer prevention

Evidence from observational studies was conflicting on the effect of aspirin in breast cancer prevention; a randomized controlled trial showed that aspirin had no significant effect in reducing breast cancer, thus further studies are needed to clarify the effect of aspirin in cancer prevention.

In gardening

There are many anecdotal reportings that aspirin can improve plant's growth and resistance though most research involved salicylic acid instead of aspirin.

Veterinary medicine

Aspirin is sometimes used in veterinary medicine as an anticoagulant or to relieve pain associated with musculoskeletal inflammation or osteoarthritis. Aspirin should be given to animals only under the direct supervision of a veterinarian, as adverse effects—including gastrointestinal issues—are common. An aspirin overdose in any species may result in salicylate poisoning, characterized by hemorrhaging, seizures, coma, and even death.

Dogs are better able to tolerate aspirin than cats are. Cats metabolize aspirin slowly because they lack the glucuronide conjugates that aid in the excretion of aspirin, making it potentially toxic if dosing is not spaced out properly. No clinical signs of toxicosis occurred when cats were given 25 mg/kg of aspirin every 48 hours for 4 weeks, but the recommended dose for relief of pain and fever and for treating blood clotting diseases in cats is 10 mg/kg every 48 hours to allow for metabolization.

References

- McTavish J (Fall 1987). "What's in a Name? Aspirin and the American Medical Association". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 61 (3): 343–366. JSTOR 44442097. PMID 3311247.

- "Aspirin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- "OTC medicine monograph: Aspirin tablets for oral use". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- "Poisons Standard October 2022". Australian Government Federal Register of Legislation. 26 September 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- "Aspirin Product information". Health Canada. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Zorprin, Bayer Buffered Aspirin (aspirin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ Brayfield A, ed. (14 January 2014). "Aspirin". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- CID 2244 from PubChem

- ^ Haynes WM, ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 3.8. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ "Aspirin". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017 – via Drugs.com.

- ^ Jones A (2015). Chemistry: An Introduction for Medical and Health Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-470-09290-3.

- Ravina E (2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. p. 24. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- ^ Jeffreys D (2008). Aspirin the remarkable story of a wonder drug. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-59691-816-0. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Felix Hoffmann". Science History Institute. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ Mann CC, Plummer ML (1991). The aspirin wars: money, medicine, and 100 years of rampant competition (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-394-57894-1.

- ^ Warner TD, Mitchell JA (October 2002). "Cyclooxygenase-3 (COX-3): filling in the gaps toward a COX continuum?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (21): 13371–3. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9913371W. doi:10.1073/pnas.222543099. PMC 129677. PMID 12374850.

- World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- "Aspirin Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- Dick B (2018). "Hard Work and Happenstance". Distillations. Vol. 4, no. 1. Science History Institute. pp. 44–45.

- ^ "Aspirin". Chemical & Engineering News. Vol. 83, no. 25. 20 June 2005.

- Reynolds EF, ed. (1982). "Aspirin and similar analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents". Martindale: the extra pharmacopoeia (28th ed.). Rittenhouse Book Distributors. pp. 234–82. ISBN 978-0-85369-160-0.

- "Acetylsalicylic acid". NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017.

- "Appendix G: 1989 Air contaminants update project – Exposure limits NOT in effect". NIOSH pocket guide to chemical hazards. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 13 February 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017.

- Palleros DR (2000). Experimental organic chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-471-28250-1.

- "Chemical of the Week -- Acetic Acid and Acetic Anhydride". www.eng.uwaterloo.ca. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022.

- Barrans R (18 May 2008). "Aspirin aging". Newton BBS. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008.

- Carstensen JT, Attarchi F (April 1988). "Decomposition of aspirin in the solid state in the presence of limited amounts of moisture III: Effect of temperature and a possible mechanism". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 77 (4): 318–21. doi:10.1002/jps.2600770407. PMID 3379589.

- Myers RL (2007). The 100 most important chemical compounds: a reference guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013.

- "Acetylsalicylic acid". Jinno Laboratory, School of Materials Science, Toyohashi University of Technology. 4 March 1996. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ Bučar DK, Lancaster RW, Bernstein J (June 2015). "Disappearing polymorphs revisited". Angewandte Chemie. 54 (24): 6972–6993. doi:10.1002/anie.201410356. PMC 4479028. PMID 26031248.

- Vishweshwar P, McMahon JA, Oliveira M, Peterson ML, Zaworotko MJ (December 2005). "The predictably elusive form II of aspirin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (48): 16802–16803. doi:10.1021/ja056455b. PMID 16316223.

- Bond AD, Boese R, Desiraju GR (2007). "On the polymorphism of aspirin: crystalline aspirin as intergrowths of two "polymorphic" domains". Angewandte Chemie. 46 (4): 618–622. doi:10.1002/anie.200603373. PMID 17139692.

- "Polytypism - Online Dictionary of Crystallography". reference.iucr.org.

- Crowell EL, Dreger ZA, Gupta YM (15 February 2015). "High-pressure polymorphism of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin): Raman spectroscopy". Journal of Molecular Structure. 1082: 29–37. Bibcode:2015JMoSt1082...29C. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.10.079. ISSN 0022-2860.

- Shtukenberg AG, Hu CT, Zhu Q, Schmidt MU, Xu W, Tan M, et al. (7 June 2017). "The Third Ambient Aspirin Polymorph". Crystal Growth & Design. 17 (6): 3562–3566. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00673. ISSN 1528-7483. OSTI 1373897.

- Vane JR (June 1971). "Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs". Nature. 231 (25): 232–5. doi:10.1038/newbio231232a0. PMID 5284360.

- Vane JR, Botting RM (June 2003). "The mechanism of action of aspirin". Thrombosis Research. 110 (5–6): 255–8. doi:10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00379-7. PMID 14592543.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1982". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017.

- "Aspirin in heart attack and stroke prevention". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- Tohgi H, Konno S, Tamura K, Kimura B, Kawano K (October 1992). "Effects of low-to-high doses of aspirin on platelet aggregability and metabolites of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin". Stroke. 23 (10): 1400–3. doi:10.1161/01.STR.23.10.1400. PMID 1412574.

- Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, et al. (May 2009). "Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials". Lancet. 373 (9678): 1849–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. PMC 2715005. PMID 19482214.

- Goel A, Aggarwal S, Partap S, Saurabh A, Choudhary (2012). "Pharmacokinetic solubility and dissolution profile of antiarrythmic drugs". Int J Pharma Prof Res. 3 (1): 592–601.

- Clària J, Serhan CN (October 1995). "Aspirin triggers previously undescribed bioactive eicosanoids by human endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (21): 9475–9479. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.9475C. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.21.9475. PMC 40824. PMID 7568157.

- Martínez-González J, Badimon L (2007). "Mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular effects of COX-inhibition: benefits and risks". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 13 (22): 2215–27. doi:10.2174/138161207781368774. PMID 17691994.

- Funk CD, FitzGerald GA (November 2007). "COX-2 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 50 (5): 470–9. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e318157f72d. PMID 18030055. S2CID 39103383.

- Romano M, Cianci E, Simiele F, Recchiuti A (August 2015). "Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins in resolution of inflammation". European Journal of Pharmacology. 760: 49–63. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.083. PMID 25895638.

- Serhan CN, Chiang N (August 2013). "Resolution phase lipid mediators of inflammation: agonists of resolution". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 13 (4): 632–40. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.012. PMC 3732499. PMID 23747022.

- Weylandt KH (August 2016). "Docosapentaenoic acid derived metabolites and mediators - The new world of lipid mediator medicine in a nutshell". European Journal of Pharmacology. 785: 108–115. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.002. PMID 26546723.

- Somasundaram S, Sigthorsson G, Simpson RJ, Watts J, Jacob M, Tavares IA, et al. (May 2000). "Uncoupling of intestinal mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and inhibition of cyclooxygenase are required for the development of NSAID-enteropathy in the rat". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 14 (5): 639–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00723.x. PMID 10792129. S2CID 44832283.

- Paul-Clark MJ, Van Cao T, Moradi-Bidhendi N, Cooper D, Gilroy DW (July 2004). "15-epi-lipoxin A4-mediated induction of nitric oxide explains how aspirin inhibits acute inflammation". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 200 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1084/jem.20040566. PMC 2213311. PMID 15238606.

- McCarty MF, Block KI (September 2006). "Preadministration of high-dose salicylates, suppressors of NF-kappaB activation, may increase the chemosensitivity of many cancers: an example of proapoptotic signal modulation therapy". Integrative Cancer Therapies. 5 (3): 252–68. doi:10.1177/1534735406291499. PMID 16880431.

- Silva Caldas AP, Chaves LO, Linhares Da Silva L, De Castro Morais D, Gonçalves Alfenas RD (29 December 2017). "Mechanisms involved in the cardioprotective effect of avocado consumption: A systematic review". International Journal of Food Properties. 20 (sup2): 1675–1685. doi:10.1080/10942912.2017.1352601. ISSN 1094-2912.

...there was postprandial reduction on the plasma concentration of IL-6 and IkBα preservation, followed by the lower activation of NFκB, considered the main transcription factor capable of inducing inflammatory response by stimulating the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules.

- Chen L, Deng H, Cui H, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng J, et al. (January 2018). "Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs". Oncotarget. 9 (6): 7204–7218. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23208. PMC 5805548. PMID 29467962.

- Lawrence T (December 2009). "The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 1 (6): a001651. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. PMC 2882124. PMID 20457564.

- Hawley SA, Fullerton MD, Ross FA, Schertzer JD, Chevtzoff C, Walker KJ, et al. (May 2012). "The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase". Science. 336 (6083): 918–22. Bibcode:2012Sci...336..918H. doi:10.1126/science.1215327. PMC 3399766. PMID 22517326.

- "Clues to aspirin's anti-cancer effects revealed". New Scientist. 214 (2862): 16. 28 April 2012. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(12)61073-2.

- Alfonso LF, Srivenugopal KS, Arumugam TV, Abbruscato TJ, Weidanz JA, Bhat GJ (March 2009). "Aspirin inhibits camptothecin-induced p21CIP1 levels and potentiates apoptosis in human breast cancer cells". International Journal of Oncology. 34 (3): 597–608. doi:10.3892/ijo_00000185. PMID 19212664.

- Alfonso LF, Srivenugopal KS, Bhat GJ (2009). "Does aspirin acetylate multiple cellular proteins? (Review)". Molecular Medicine Reports (review). 2 (4): 533–7. doi:10.3892/mmr_00000132. PMID 21475861.

- Alfonso LF, Srivenugopal KS, Bhat GJ (4 June 2009). "Does aspirin acetylate multiple cellular proteins? (Review)". Molecular Medicine Reports. 2 (4): 533–537. doi:10.3892/mmr_00000132. PMID 21475861.

- Franchi F, Schneider D, Prats J, Fan W, Rollini F, Been L, et al. (2021). "TCT-320 Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Profile of PL-ASA, a Novel Phospholipid-Aspirin Complex Liquid Formulation, Compared to Enteric-Coated Aspirin at an 81-mg Dose – Results From a Prospective, Randomized, Crossover Study". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 78 (19). Elsevier BV: B131. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.1173. ISSN 0735-1097.

- Ferguson RK, Boutros AR (August 1970). "Death following self-poisoning with aspirin". JAMA. 213 (7): 1186–8. doi:10.1001/jama.213.7.1186. PMID 5468267.

- Kaufman FL, Dubansky AS (April 1972). "Darvon poisoning with delayed salicylism: a case report". Pediatrics. 49 (4): 610–1. doi:10.1542/peds.49.4.610. PMID 5013423. S2CID 29427204.

- ^ Levy G, Tsuchiya T (August 1972). "Salicylate accumulation kinetics in man". The New England Journal of Medicine. 287 (9): 430–2. doi:10.1056/NEJM197208312870903. PMID 5044917.

- Grootveld M, Halliwell B (January 1988). "2,3-Dihydroxybenzoic acid is a product of human aspirin metabolism". Biochemical Pharmacology. 37 (2): 271–80. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(88)90729-0. PMID 3342084.

- Hartwig-Otto H (November 1983). "Pharmacokinetic considerations of common analgesics and antipyretics". The American Journal of Medicine. 75 (5A): 30–7. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(83)90230-9. PMID 6606362.

- Done AK (November 1960). "Salicylate intoxication. Significance of measurements of salicylate in blood in cases of acute ingestion". Pediatrics. 26: 800–7. doi:10.1542/peds.26.5.800. PMID 13723722. S2CID 245036862.

- Chyka PA, Erdman AR, Christianson G, Wax PM, Booze LL, Manoguerra AS, et al. (2007). "Salicylate poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management". Clinical Toxicology. 45 (2): 95–131. doi:10.1080/15563650600907140. PMID 17364628.

- Prescott LF, Balali-Mood M, Critchley JA, Johnstone AF, Proudfoot AT (November 1982). "Diuresis or urinary alkalinisation for salicylate poisoning?". British Medical Journal. 285 (6352): 1383–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6352.1383. PMC 1500395. PMID 6291695.

- Dargan PI, Wallace CI, Jones AL (May 2002). "An evidence based flowchart to guide the management of acute salicylate (aspirin) overdose". Emergency Medicine Journal. 19 (3): 206–9. doi:10.1136/emj.19.3.206. PMC 1725844. PMID 11971828.

- ^ D'Agati V (July 1996). "Does aspirin cause acute or chronic renal failure in experimental animals and in humans?". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 28 (1 Suppl 1): S24-9. doi:10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90565-x. PMID 8669425.

- Goldberg DR (Summer 2009). "Aspirin: Turn of the Century Miracle Drug". Chemical Heritage. Vol. 27, no. 2. pp. 26–30.

- Diarmuid Jeffreys (2004). Aspirin: the Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug. Bloomsbury. p. 18-34.

- Schiebinger L (October 2003). "Women's health and clinical trials". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 112 (7): 973–7. doi:10.1172/JCI19993. PMC 198535. PMID 14523031.

- "Regular aspirin intake and acute myocardial infarction". British Medical Journal. 1 (5905): 440–3. March 1974. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5905.440. PMC 1633212. PMID 4816857.

- Elwood PC, Cochrane AL, Burr ML, Sweetnam PM, Williams G, Welsby E, et al. (March 1974). "A randomized controlled trial of acetyl salicylic acid in the secondary prevention of mortality from myocardial infarction". British Medical Journal. 1 (5905): 436–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5905.436. PMC 1633246. PMID 4593555.

- Bayer Co. v. United Drug Co., 272 F. 505, p.512 (S.D.N.Y 1921).

- "Has aspirin become a generic trademark?". genericides.org. 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- Huth EJ, et al. (CBE Style Manual Committee) (1994). Scientific style and format: the CBE manual for authors, editors, and publishers. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. Bibcode:1994ssfc.book.....S. ISBN 978-0-521-47154-1. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

- "Aspirin: the versatile drug". CBC News. 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016.

- Cheng TO (2007). "The history of aspirin". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 34 (3): 392–3. PMC 1995051. PMID 17948100.

- "Aspirin". Sigma Aldrich. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Index BP 2009" (PDF). British Pharmacopoeia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Aspirin for reducing your risk of heart attack and stroke: know the facts". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Aspirin for reducing your risk of heart attack and stroke: know the facts". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, Sivakumaran R, Nethercott S, Erqou S, Sattar N, et al. (February 2012). "Effect of aspirin on vascular and nonvascular outcomes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Internal Medicine. 172 (3): 209–16. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.628. hdl:10044/1/34287. PMID 22231610.

- McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, Reid CM, Kirpach B, Wolfe R, et al. (October 2018). "Effect of Aspirin on Disability-free Survival in the Healthy Elderly". The New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (16): 1499–1508. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800722. hdl:1885/154654. PMC 6426126. PMID 30221596.

- McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, Tonkin AM, Donnan GA, Nelson MR, et al. (October 2018). "Effect of Aspirin on Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding in the Healthy Elderly". The New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (16): 1509–1518. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1805819. PMC 6289056. PMID 30221597.

- ^ Algra AM, Rothwell PM (May 2012). "Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials". The Lancet. Oncology. 13 (5): 518–27. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2. PMID 22440112.

- Sachs CJ (March 2005). "Oral analgesics for acute nonspecific pain". American Family Physician. 71 (5): 913–8. PMID 15768621.

- Gaciong Z (June 2003). "The real dimension of analgesic activity of aspirin". Thrombosis Research. 110 (5–6): 361–4. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2003.08.009. PMID 14592563.

- Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (December 2014). "Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (12): CD009281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub3. PMC 6485702. PMID 25502052.

- Hersh EV, Moore PA, Ross GL (May 2000). "Over-the-counter analgesics and antipyretics: a critical assessment". Clinical Therapeutics. 22 (5): 500–48. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80043-0. PMID 10868553.

- Mett A, Tfelt-Hansen P (June 2008). "Acute migraine therapy: recent evidence from randomized comparative trials". Current Opinion in Neurology. 21 (3): 331–7. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282fee843. PMID 18451718. S2CID 44459366.

- Kingery WS (November 1997). "A critical review of controlled clinical trials for peripheral neuropathic pain and complex regional pain syndromes". Pain. 73 (2): 123–139. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00049-3. PMID 9415498. S2CID 10418793.

- Loder E, Rizzoli P (January 2008). "Tension-type headache". BMJ. 336 (7635): 88–92. doi:10.1136/bmj.39412.705868.AD. PMC 2190284. PMID 18187725.

- Gilmore B, Michael M (February 2011). "Treatment of acute migraine headache". American Family Physician. 83 (3): 271–80. PMID 21302868.

- Bartfai T, Conti B (March 2010). "Fever". TheScientificWorldJournal. 10: 490–503. doi:10.1100/tsw.2010.50. PMC 2850202. PMID 20305990.

- Pugliese A, Beltramo T, Torre D (October 2008). "Reye's and Reye's-like syndromes". Cell Biochemistry and Function. 26 (7): 741–6. doi:10.1002/cbf.1465. PMID 18711704. S2CID 22361194.

- Beutler AI, Chesnut GT, Mattingly JC, Jamieson B (December 2009). "FPIN's Clinical Inquiries. Aspirin use in children for fever or viral syndromes". American Family Physician. 80 (12): 1472. PMID 20000310.

- "Medications Used to Treat Fever". American Academy of Pediatrics. 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "51 FR 8180" (PDF). United States Federal Register. 51 (45). 7 March 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2011.

- Morris T, Stables M, Hobbs A, de Souza P, Colville-Nash P, Warner T, et al. (August 2009). "Effects of low-dose aspirin on acute inflammatory responses in humans". Journal of Immunology. 183 (3): 2089–96. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900477. PMID 19597002.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) (July 2013). "Adjunctive pharmacotherapy and associated NICE guidance". Myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: the acute management of myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation . NICE Clinical Guidelines. Royal College of Physicians (UK). 17.2 Aspirin. PMID 25340241. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- ^ Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. (September 2019). "2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 74 (10): e177 – e232. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010. PMC 7685565. PMID 30894318.

- ^ Rothwell PM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, Price JF, Belch JF, Roncaglioni MC, et al. (August 2018). "Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials". Lancet. 392 (10145): 387–399. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31133-4. PMC 6083400. PMID 30017552.

- Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, Stevens W, Buck G, Barton J, et al. (October 2018). "Effects of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus". The New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (16): 1529–1539. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1804988. PMID 30146931.

- McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, Tonkin AM, Donnan GA, Nelson MR, et al. (October 2018). "Effect of Aspirin on Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding in the Healthy Elderly". The New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (16): 1509–1518. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1805819. PMC 6289056. PMID 30221597.

- Woods RL, Polekhina G, Wolfe R, Nelson MR, Ernst ME, Reid CM, et al. (March 2020). "No Modulation of the Effect of Aspirin by Body Weight in Healthy Older Men and Women". Circulation. 141 (13): 1110–1112. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044142. PMC 7286412. PMID 32223674.

- National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). "2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary artery intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions". United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK (August 2001). "Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 345 (7): 494–502. doi:10.1056/nejmoa010746. PMID 11519503. S2CID 15459216.

- Costa F, Vranckx P, Leonardi S, Moscarella E, Ando G, Calabro P, et al. (May 2015). "Impact of clinical presentation on ischaemic and bleeding outcomes in patients receiving 6- or 24-month duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after stent implantation: a pre-specified analysis from the PRODIGY (Prolonging Dual-Antiplatelet Treatment After Grading Stent-Induced Intimal Hyperplasia) trial". European Heart Journal. 36 (20): 1242–51. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(15)61590-x. PMID 25718355.

- Khan SU, Singh M, Valavoor S, Khan MU, Lone AN, Khan MZ, et al. (October 2020). "Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Drug-Eluting Stents: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis". Circulation. 142 (15): 1425–1436. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046308. PMC 7547897. PMID 32795096.

- Capodanno D, Alfonso F, Levine GN, Valgimigli M, Angiolillo DJ (December 2018). "ACC/AHA Versus ESC Guidelines on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: JACC Guideline Comparison". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 72 (23 Pt A): 2915–2931. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.057. PMID 30522654.

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, et al. (September 2016). "2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 68 (10): 1082–115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.513. PMID 27036918.

- Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, et al. (January 2018). "2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)". European Heart Journal. 39 (3): 213–260. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419. PMID 28886622.