This is an old revision of this page, as edited by CheMoBot (talk | contribs) at 07:22, 6 December 2011 (Updating {{drugbox}} (no changed fields - added verified revid) per Chem/Drugbox validation (report errors or bugs)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:22, 6 December 2011 by CheMoBot (talk | contribs) (Updating {{drugbox}} (no changed fields - added verified revid) per Chem/Drugbox validation (report errors or bugs))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Concerta" redirects here. For the musical composition, see Concerto. For the implantable defibrillator named Medtronic Concerto, see defibrillator. Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Concerta, Methylin, Ritalin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682188 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, Transdermal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 11–52% |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | Liver (80%) |

| Elimination half-life | 2–4 hours |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.662 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H19NO2 |

| Molar mass | 233.31 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 214 °C (417 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Methylphenidate (Ritalin, MPH, MPD) is a psychostimulant drug approved for treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and narcolepsy. It may also be prescribed for off-label use in treatment-resistant cases of lethargy, depression, neural insult and obesity. Methylphenidate belongs to the piperidine class of compounds and increases the levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain through reuptake inhibition of the monoamine transporters. Methylphenidate possesses structural similarities to amphetamine and its pharmacological effects are more similar to those of cocaine, though MPH is less potent and longer in duration of action.

Medical uses

MPH is the most commonly prescribed psychostimulant and works by increasing the activity of the central nervous system. It produces such effects as increasing or maintaining alertness, combating fatigue, and improving attention. The short-term benefits and cost effectiveness of methylphenidate are well established, although long-term effects are unknown. The long term effects of methylphenidate on the developing brain are unknown. Methylphenidate is not approved for children under six years of age.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Methylphenidate is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder The addition of behavioural modification therapy (e.g. cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)) has additional benefits on treatment outcome. There is a lack of evidence of the effectiveness in the long term of beneficial effects of methylphenidate with regard to learning and academic performance. One study found that pharmacological treatment of ADHD in childhood reduces the risk that children will resort to substance abuse in adolescence by 85%, while untreated ADHD was a significant risk factor in developing substance abuse. A meta analysis of the literature concluded that methylphenidate quickly and effectively reduces the signs and symptoms of ADHD in children under the age of 18 in the short term but found that this conclusion may be biased due to the high number of low quality clinical trials in the literature. There have been no placebo controlled trials investigating the long term effectiveness of methylphenidate beyond 4 weeks thus the long term effectiveness of methylphenidate has not been scientifically demonstrated. Serious concerns of publication bias regarding the use of methylphenidate for ADHD have also been noted. A diagnosis of ADHD must be confirmed and the benefits and risks and proper use of stimulants as well as alternative treatments should be discussed with the parent before stimulants are prescribed. The dosage used can vary quite significantly from individual child to individual child with some children responding to quite low doses whereas other children require the higher dose range. The dose, therefore, should be titrated to an optimal level that achieves therapeutic benefit and minimal side-effects. This can range from anywhere between 5–30 mg twice daily or up to 60 mg a day. Therapy with methylphenidate should not be indefinite. Weaning off periods to assess symptoms are recommended.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy, a chronic sleep disorder characterized by overwhelming daytime drowsiness and sudden need for sleep, is treated primarily with stimulants. Methylphenidate is considered effective in increasing wakefulness, vigilance, and performance. Methylphenidate improves measures of somnolence on standardized tests, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test, but performance does not improve to levels comparable to healthy controls.

Adjunctive

Use of stimulants such as methylphenidate in cases of treatment resistant depression is controversial. In individuals with cancer, methylphenidate is commonly used to counteract opioid-induced somnolence, to increase the analgesic effects of opioids, to treat depression, and to improve cognitive function. Methylphenidate may be used in addition to an antidepressant for treatment-refractory major depressive disorder. It can also improve depression in several groups including stroke, cancer, and HIV-positive patients. However, benefits tend to be only partial with stimulants being, in general, less effective than traditional antidepressants and there is some suggestive evidence of a risk of habituation. Stimulants may however, have fewer side-effects than tricyclic antidepressants in the elderly and medically ill. A review of the literature found that methylphenidate was ineffective for refractory cases of major depression.

Substance dependence

Methylphenidate has shown some benefits as a replacement therapy for individuals dependent on methamphetamine. Cocaine and methamphetamine interfere with the protein DAT, over time causing DAT upregulation and lower cytoplasmic dopamine levels in their absence. Methylphenidate and amphetamine have been investigated as a chemical replacement for the treatment of cocaine dependence in the same way that methadone is used as a replacement for heroin. Its effectiveness in treatment of cocaine or other psychostimulant dependence has not been proven and further research is needed.

Early research began in 2007–2008 in some countries on the effectiveness of methylphenidate as a substitute agent in refractory cases of cocaine dependence, owing to methylphenidate's longer half life, and reduced vasoconstrictive effects. This replacement therapy is used in other classes of drugs such as opiates for maintenance and gradual withdrawal such as methadone, suboxone, etc.

Pervasive developmental disorders

Given the high comorbidity between ADHD and autism, a few studies have examined the efficacy and effectiveness of methylphenidate in the treatment of autism. However, most of these studies examined the effects of methylphenidate on attention and hyperactivity symptoms among children with autism spectrum disorders. Aman and Langworthy (2000) attempted to examine the effects of methylphenidate on social-communication and self-regulation behaviors among children with disorders.

The sample included 33 children with pervasive developmental disorder (29 boys) with a mean age of 6.93 years (range 5–13). This was a 4-week randomized, double-blind, cross-over placebo study, with treatment changing each week between 4 conditions: placebo, low dose, medium dose, and high dose. In this design, neither the experimenters nor the families know which of the 4 treatments the child is receiving at any given time. In addition, the treatment condition changes randomly each week, without anyone knowing the nature of the old or new condition. This allows the experimenters to assume that consistent changes in behaviors that occur during a particular treatment is truly due to the effect of that treatment and not to the expectation of the treatment (placebo effect).

The results indicate that children showed significantly more joint attention behaviors when receiving methylphenidate than when receiving the placebo (although the most effective dosage varied by individual). Furthermore, at a group level, the low dose of methylphenidate resulted in significantly improved joint attention behaviors when compared to the placebo, but no differences were noted between the low, medium, and high doses. Low and medium doses of methylphenidate also resulted in improved self-regulation behavior when compared to placebo.

The study presents compelling preliminary evidence suggesting that methylphenidate is effective in improving some social behaviors among children with autism spectrum disorders.

Investigational

Animal studies using rats with ADHD-like behaviours were used to assess the safety of methylphenidate on the developing brain and found that psychomotor impairments, structural and functional parameters of the dopaminergic system were improved with treatment. This animal data suggests that methylphenidate supports brain development and hyperactivity in children diagnosed with ADHD. However, in normal control animals methylphenidate caused long lasting changes to the dopaminergic system suggesting that if a child is misdiagnosed with ADHD they may be at risk of long lasting adverse effects to brain development. Animal tests found that rats given methylphenidate grew up to be more stressed and emotional. It is unclear due to lack of followup study whether this occurs in ADHD like animals and whether it occurs in humans. However, long lasting benefits of stimulant drugs have not been found in humans.

Pregnancy

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gives methylphenidate a pregnancy category of C, and women are advised to only use the drug if the benefits outweigh the potential risks. Not enough animal and human studies have been conducted to conclusively demonstrate an effect of methylphenidate on fetal development. In 2007, empirical literature included 63 cases of prenatal exposure to methylphenidate across three empirical studies. One of these studies (N = 11) demonstrated no significant increases in malformations. A second (N = 13) demonstrated one major malformation in newborns with early exposure to methylphenidate, which was in the expected range of malformations. However, this was a cardiac malformation, which was not within the statistically expected range. Finally, in a retrospective analysis of patients' medical charts (N = 38), researchers examined the relationship between abuse of intravenous methylphenidate and pentazocine in pregnant women. Twenty-one percent of these children were born prematurely, and several had stunted growth and withdrawal symptoms (31% and 28%, respectively). Intravenous methylphenidate abuse was confounded with the concurrent use of other substances (e.g., cigarettes, alcohol) during pregnancy.

Adverse effects

Some adverse effects may emerge during chronic use of methylphenidate so a constant watch for adverse effects is recommended. Some adverse effects of stimulant therapy may emerge during long-term therapy, but there is very little research of the long-term effects of stimulants. The most common side effects of methylphenidate are nervousness, drowsiness and insomnia. Other adverse reactions include:

- Abdominal pain

- Akathisia

- Alopecia

- Angina

- Appetite loss

- Anxiety

- Blood pressure and pulse changes (both up and down)

- Cardiac arrhythmia

- Diaphoresis (sweating)

- Dizziness

- Dyskinesia

- Headaches

- Hypersensitivity (including skin rash, urticaria, fever, arthralgia, exfoliative dermatitis, erythema multiforme, necrotizing vasculitis, and thrombocytopenic purpura)

- Lethargy

- Libido increased or decreased

- Nausea

- Palpitations

- Pupil dilation

- Psychosis

- Short-term weight loss

- Somnolence

- Stunted growth

- Tachycardia

- Xerostomia (dry mouth)

Risks to health

Researchers have also looked into the role of methylphenidate in affecting stature, with some studies finding slight decreases in height acceleration. Other studies indicate height may normalize by adolescence. In a 2005 study, only "minimal effects on growth in height and weight were observed" after 2 years of treatment. "No clinically significant effects on vital signs or laboratory test parameters were observed."

A 2003 study tested the effects of dexmethylphenidate (Focalin), levomethylphenidate, and (racemic) dextro-, levomethylphenidate (Ritalin) on mice to search for any carcinogenic effects. The researchers found that all three preparations were non-genotoxic and non-clastogenic; d-MPH, d, l-MPH, and l-MPH did not cause mutations or chromosomal aberrations. They concluded that none of the compounds present a carcinogenic risk to humans. Current scientific evidence supports that long-term methylphenidate treatment does not increase the risk of developing cancer in humans.

It was documented in 2000, by Zito et al. "that at least 1.5% of children between the ages of two and four are medicated with stimulants, anti-depressants and anti-psychotic drugs, despite the paucity of controlled scientific trials confirming safety and long-term effects with preschool children."

On March 22, 2006, the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee decided that medications using methylphenidate ingredients do not need black box warnings about their risks, noting that "for normal children, these drugs do not appear to pose an obvious cardiovascular risk." Previously, 19 possible cases had been reported of cardiac arrest linked to children taking methylphenidate and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee to the FDA recommend a "black-box" warning in 2006 for stimulant drugs used to treat attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Doses prescribed of stimulants above the recommended dose level is associated with higher levels of psychosis, substance misuse and psychiatric admissions.

Long-term effects

The effects of long-term methylphenidate treatment on the developing brains of children with ADHD is the subject of study and debate. Although the safety profile of short-term methylphenidate therapy in clinical trials has been well established, repeated use of psychostimulants such as methylphenidate is less clear. There are no well defined withdrawal schedules for discontinuing long-term use of stimulants. There is limited data that suggests there are benefits to long-term treatment in correctly diagnosed children with ADHD, with overall modest risks. Short-term clinical trials lasting a few weeks show an incidence of psychosis of about 0.1%. A small study of just under 100 children that assessed long-term outcome of stimulant use found that 6% of children became psychotic after months or years of stimulant therapy. Typically, psychosis would abate soon after stopping stimulant therapy. As the study size was small, larger studies have been recommended. The long-term effects on mental health disorders in later life of chronic use of methylphenidate is unknown. Concerns have been raised that long-term therapy might cause drug dependence, paranoia, schizophrenia and behavioral sensitisation, similar to other stimulants. Psychotic symptoms from methylphenidate can include hearing voices, visual hallucinations, urges to harm oneself, severe anxiety, euphoria, grandiosity, paranoid delusions, confusion, increased aggression and irritability. Methylphenidate psychosis is unpredictable in whom it will occur. Family history of mental illness does not predict the incidence of stimulant toxicosis in children with ADHD. High rates of childhood stimulant use is found in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder independent of ADHD. Individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar or schizophrenia who were prescribed stimulants during childhood typically have a significantly earlier onset of the psychotic disorder and suffer a more severe clinical course of psychotic disorder. Knowledge of the effects of chronic use of methylphenidate is poorly understood with regard to persisting behavioral and neuroadaptational effects.

Tolerance and behavioural sensitisation may occur with long-term use of methylphenidate. There is also cross tolerance with other stimulants such as amphetamines and cocaine. Stimulant withdrawal or rebound reactions can occur and should be minimised in intensity, e.g. via a gradual tapering off of medication over a period of weeks or months. A very small study of abrupt withdrawal of stimulants did suggest that withdrawal reactions are not typical. Nonetheless, withdrawal reactions may still occur in susceptible individuals. The withdrawal or rebound symptoms of methylphenidate can include psychosis, depression, irritability and a temporary worsening of the original ADHD symptoms. Methylphenidate, due to its very short elimination half life, may be more prone to rebound effects than d-amphetamine. Up to a third of children with ADHD experience a rebound effect when methylphenidate dose wears off.

Interactions

Intake of adrenergic agonist drugs or pemoline with methylphenidate increases the risk of liver toxicity. Antidepressants taken in conjunction with methylphenidate may cause hypertension, hypothermia and convulsions. When methylphenidate is coingested with ethanol, a metabolite called ethylphenidate is formed via hepatic transesterification, not unlike the hepatic formation of cocaethylene from cocaine and alcohol. Coingestion of alcohol (ethanol) also increases the blood plasma levels of d-methylphenidate by up to 40%. Ethylphenidate is more selective to the dopamine transporter (DAT) than methylphenidate, having approximately the same efficacy as the parent compound, but has significantly less activity on the norepinephrine transporter (NET).

Contraindications

Methylphenidate should not be prescribed concomitantly with tricyclic antidepressants, such as desipramine, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as phenelzine or tranylcypromine, as methylphenidate may dangerously increase plasma concentrations, leading to potential toxic reactions (mainly, cardiovascular effects). Methylphenidate should not be prescribed to patients who suffer from severe arrhythmia, hypertension or liver damage. It should not be prescribed to patients who demonstrate drug-seeking behaviour, pronounced agitation or nervousness. Care should be taken while prescribing methylphenidate to children with a family history of Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia (PSVT).

Special precautions

Special precaution is recommended in individuals with epilepsy with additional caution in individuals with uncontrolled epilepsy due to the potential for methylphenidate to lower the seizure threshold.

Abuse potential

Methylphenidate has high potential for abuse due to its pharmacological similarity to cocaine and amphetamines. Methylphenidate, like other stimulants, increases dopamine levels in the brain, but at therapeutic doses this increase is slow, and thus euphoria does not typically occur except in rare instances. The abuse potential is increased when methylphenidate is crushed and insufflated (snorted), or when it is injected, producing effects almost identical to cocaine. Cocaine-like effects can also occur with very large doses taken orally. The dose, however, that produces euphoric effects varies between individuals. Methylphenidate is actually more potent than cocaine in its effect on dopamine transporters. Methylphenidate should not be viewed as a weak stimulant as has previously been hypothesised.

The primary source of methylphenidate for abuse is diversion from legitimate prescriptions, rather than illicit synthesis. Those who use it to stay awake do so by taking it orally, while intranasal and intravenous are the preferred means for inducing euphoria. IV users tend to be adults whose use may cause panlobular pulmonary emphysema.

Abuse of prescription stimulants is higher amongst college students than non-college attending young adults. College students use methylphenidate either as a study aid or to stay awake longer. Increased alcohol consumption due to stimulant misuse has additional negative effects on health. Methylphenidate's pharmacological effect on the central nervous system is almost identical to that of cocaine. Studies have shown that the two drugs are nearly indistinguishable when administered intravenously to cocaine addicts.

However, cocaine has a slightly higher affinity for the dopamine receptor in comparison to methylphenidate, which is thought to be the mechanism of the euphoria associated with the relatively short-lived cocaine high. Reports of users experimenting with mixing methylphenidate with caffeine and benzocaine to produce a powder for insufflation (snorting) for an even more cocaine-like effect began to appear in the middle 1970s; this is apparently an incrementation upon a mixture known as Toot containing phenylpropanolamine, caffeine, and benzocaine in the search for legal highs. As moderate doses of cocaine have caffeine-like effects and benzocaine produces a slight stimulant effect of its own perhaps 5% the strength of cocaine with a ceiling in that range, the mixture is reported to have at least some of the sought-after effects.

Patients who have been prescribed Ritalin have been known to sell their tablets to others who wish to take the drug recreationally. In the USA it is one of the top ten stolen prescription drugs and is known as "kiddie coke", "Vitamin R" and "The R Ball". Recreational users may crush the tablets and either snort the powder, or dissolve the powder in water, filter it through cotton wool into a syringe to remove the inactive ingredients and other particles and inject the drug intravenously. Both of these methods increase bioavailability and produce a much more rapid onset of effects than when taken orally (within c.5–10 minutes through insufflation and within just 10–15 seconds through intravenous injection); however the overall duration of action tends to be decreased by any non-oral use of drug preparations made for oral use.

Methylphenidate is sometimes used by students to enhance their mental abilities, improving their concentration and helping them to study. Professor John Harris, an expert in bioethics, has said that it would be unethical to stop healthy people taking the drug. He also argues that it would be "not rational" and against human enhancement to not use the drug to improve people's cognitive abilities. Professor Anjan Chatterjee however has warned that there is a high potential for abuse and may cause serious adverse effects on the heart, meaning that only people with an illness should take the drug. In the British Medical Journal he wrote that it was premature to endorse the use of Ritalin in this way as the effects of the drug on healthy people have not been studied. Professor Barbara Sahakian has argued that the use of Ritalin in this way may give students an unfair advantage in examinations and that as a result universities may have to consider making students give urine samples to be tested for the drug.

Overdose

In 2004, over 8000 methylphenidate ingestions were reported in US poison center data. The most common reasons for intentional exposure were drug abuse and suicide attempts. An overdose manifests in agitation, hallucinations, psychosis, lethargy, seizures, tachycardia, dysrhythmias, hypertension, and hyperthermia. Benzodiazepines may be used as treatment if agitation, dystonia, or convulsions are present.

Detection in biological fluids

The concentration of methylphenidate or ritalinic acid, its major metabolite, may be quantified in plasma, serum or whole blood in order to monitor compliance in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage.

Pharmacology

Methylphenidate is a chain substituted amphetamine derivative that primarily acts as a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor Similar to amphetamines and cocaine, a key target of methylphenidate is the dopamine transporter (DAT). Moreover, it is thought to act as a releasing agent by increasing the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, though to a much lesser extent than amphetamines. Methylphenidate's mechanism of action at dopamine-norepinephrine release is still debated, but is fundamentally different from amphetamines, as methylphenidate is thought to increase general firing rate, whereas amphetamines reverse the flow of the monoamine transporters. Although methylphenidate is an amphetamine derivative, subtle differences exist in its pharmacology; amphetamine works as a dopamine transport substrate whereas methylphenidate works as a dopamine transport blocker. Methylphenidate is most active at modulating levels of dopamine and to a lesser extent noradrenaline.

Methylphenidate has both DAT and NET binding affinity, with the dextromethylphenidate enantiomers displaying a prominent affinity for the norepinephrine transporter. Both the dextro- and levorotary enantiomers displayed receptor affinity for the serotonergic 5HT1A and 5HT2B subtypes, though direct binding to the serotonin transporter was not observed.

The enantiomers and the relative psychoactive effects and CNS stimulation of dextro- and levo-methylphenidate is analogous to what is found in amphetamine, where dextro-amphetamine is considered to have a greater psychoactive and CNS stimulatory effect than levo-amphetamine.

Pharmacodynamics

Methylphenidate exerts its therapeutic effects via blocking the reuptake of dopamine into nerve terminals (as well as stimulating the release of dopamine from dopamine nerve terminals) resulting in increased dopamine levels in the synapse. The onset of central nervous system effects occurs rapidly after intake of methylphenidate and persist for about 4 hours. The mechanism of action is comparable with that of cocaine with usual doses of both drugs occupying 50% of dopamine transporters. However, effects such as euphoria that resembles that of cocaine are rare at doses prescribed clinically.

The means by which methylphenidate affects people diagnosed with ADHD are not well understood. Some researchers have theorized that ADHD is caused by a dopamine imbalance in the brains of those affected. Methylphenidate is a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, which means that it increases the level of the dopamine neurotransmitter in the brain by partially blocking the dopamine transporter (DAT) that removes dopamine from the synapses. This inhibition of DAT blocks the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into the presynaptic neuron, increasing the amount of dopamine in the synapse. It also stimulates the release of dopamine and norepinephrine into the synapse. Finally, it increases the magnitude of dopamine release after a stimulus, increasing the salience of stimulus. An alternate explanation that has been explored is that the methylphenidate affects the action of serotonin in the brain. However, benefits with other stimulants that have a different mechanism of action indicates that support for a deficit in specific neurotransmitters is unsupported and unproven by the evidence and remains a speculative hypothesis.

Many have asked why a stimulant would be used to treat hyperactivity, as it seems paradoxical. However, MRI scans have revealed that people with ADHD show differences from non-ADHD individuals in brain regions important for attention regulation and control of impulsive behavior. Methylphenidate's cognitive enhancement effects have been investigated using fMRI scans even in non-ADHD brains, which revealed modulation of brain activity in ways that enhance mental focus. Methylphenidate increased activity in the prefrontal cortex and attention-related areas of the parietal cortex during challenging mental tasks; these are the same areas that the above study demonstrated to be shrunken in ADHD brains. Methylphenidate also increased deactivation of default network regions during the task. Thus, by modifying the activity of certain brain regions known to play important roles in the executive functions, methylphenidate stimulates mental focus and self-control.

One study finds that methylphenidate reduces the increases in brain glucose metabolism during performance of a cognitive task by about 50%. This suggests that, similar to increasing dopamine and norepinephrine in the striatum and prefrontal cortex, methylphenidate may focus activation of certain regions and make the brain more efficient. This is consistent with the observation that stimulant drugs can enhance attention and performance in some individuals. If brain resources are not optimally distributed (for example, in individuals with ADHD or sleep deprivation), improved performance could be achieved by reducing task-induced regional activation. Stimulant delivery when brain resources are already optimally distributed may then adversely affect performance.

A paper published in Biological Psychiatry reports that methylphenidate fine-tunes the functioning of neurons in the prefrontal cortex – a brain region involved in attention, decision-making and impulse control – while having few effects outside it. The team studied PFC neurons in rats under a variety of methylphenidate doses, including one that improved the animals' performance in a working memory task of the type that ADHD patients have trouble completing. Using microelectrodes, the scientists observed both the random, spontaneous firings of PFC neurons and their response to stimulation of the hippocampus. When they listened to individual PFC neurons, the scientists found that while cognition-enhancing doses of methylphenidate had little effect on spontaneous activity, the neurons' sensitivity to signals coming from the hippocampus increased dramatically. Under higher, stimulatory doses, on the other hand, PFC neurons stopped responding to incoming information.

Mechanism of action

According to research of U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory methylphenidate works in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by increasing levels of dopamine in the brain. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter, plays a role in feelings of pleasure and is naturally released in rewarding experiences. Neuroimaging studies of medication-free depressed patients have found that depressed subjects have a functional deficiency of synaptic dopamine. Dopamine decreases "background firing" rates and increases the signal to noise ratio in target neurons by increasing dopamine levels in the brain. As a result, the drug may improve attention and decrease distractibility in activities that normally do not hold the attention of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. However, sympathomimetic amines do have a dependence liability and a potential for tolerance adaptation because of their dopaminergic effects when taken in doses outside of their therapeutic range or for an extended period of time.

Chemistry

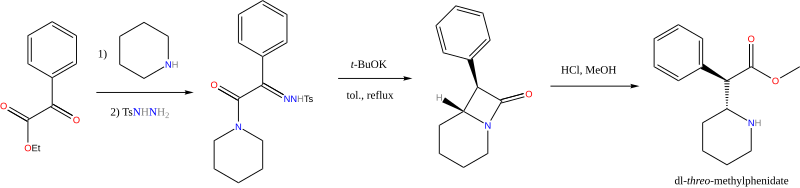

Four isomers of methylphenidate are known to exist. One pair of threo isomers and one pair of erythro are distinguished, from which only d-threo-methylphenidate exhibits the pharmacologically usually desired effects. When the drug was first introduced it was sold as a 3:1 mixture of erythro:threo diastereomers. The erythro diastereomers are also pressor amines. "TMP" is referring only to the threo product that does not contain any erythro diastereomers. Since the threo isomers are energetically favored, it is easy to epimerize out any of the undesired erythro isomers. The drug that contains only dextrorotary methylphenidate is called d-TMP. A review on the synthesis of enantiomerically pure ("R,2'R)-(+)-threo-methylphenidate hydrochloride has been published.

History

Methylphenidate was first synthesized in 1944, and was identified as a stimulant in 1954.

Methylphenidate was synthesized by Ciba (now Novartis) chemist Leandro Panizzon. His wife, Marguerite, had low blood pressure and would take the drug as a stimulant before playing tennis. He named the substance Ritaline, after his wife's nickname, Rita.

Originally it was marketed as a mixture of two racemates, 80% (±)-erythro and 20% (±)-threo. Subsequent studies of the racemates showed that the central stimulant activity is associated with the threo racemate and were focused on the separation and interconversion of the erythro isomer into the more active threo isomer.

Beginning in the 1960s, it was used to treat children with ADHD or ADD, known at the time as hyperactivity or minimal brain dysfunction (MBD). Production and prescription of methylphenidate rose significantly in the 1990s, especially in the United States, as the ADHD diagnosis came to be better understood and more generally accepted within the medical and mental health communities.

Most brand-name Ritalin is produced in the United States, and methylphenidate is produced in the United States, Mexico, Spain and Pakistan. Other generic forms, including "Methylin", "Metadate" and "Attenta" are produced by numerous pharmaceutical companies throughout the world. Ritalin is also sold in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Spain, Germany, Israel and other European countries (although in much lower volumes than in the United States). In Belgium the product is sold under the name "Rilatine" and in Brazil, Portugal and Argentina as "Ritalina". In Thailand, it is found under the name "Hynidate" Ritalina is not produced in Argentina but in Spain by Novartis Labs.

Sustained-release preparations of methylphenidate are now also available. These include various preparations (e.g. "Ritalin LA", "Equasym XL") that provide two standard doses – half the total dose being released immediately and the other half released four hours later – providing approximately eight hours of continuously sustained effect. In 2000 Janssen received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to market "Concerta", a controlled-release methylphenidate tablet providing a continuous effect for up to about 12 hours. Although, Concerta has a different time-release profile than Ritalin, with less than half of the dose being immediately released, and the remaining released in a controlled dose over the next 8–12 hours. Metadate CD, another variant of MPH time-release, acts similarly in relation to the profile of Concerta.

Legal status

- Internationally, methylphenidate is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

- In the United States, methylphenidate is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance, the designation used for substances that have a recognized medical value but present a high likelihood for abuse because of their addictive potential.

- In the United Kingdom, methylphenidate is a controlled 'Class B' substance, and possession without prescription is illegal, with a sentence up to 14 years and/or an unlimited fine.

- In New Zealand, it is a 'class B2 controlled substance'. Unlawful possession is punishable by six-month prison sentence and distribution of it is punishable by a 14-year sentence.

Available forms

The dosage forms of methylphenidate are patches, liquid, tablets, and capsules. A formulation by the Novartis trademark name Ritalin, is an instant-release racemic mixture, although a variety of formulations and generic brand names exist. Generic brand names include Ritalina, Rilatine, Attenta, Methylin, Penid, and Rubifen; and the sustained release tablets Concerta, Metadate CD, Methylin ER, Ritalin LA, and Ritalin-SR. Focalin is a preparation containing only dextro-methylphenidate, rather than the usual racemic dextro- and levo-methylphenidate mixture of other formulations. A newer way of taking methylphenidate is by using a transdermal patch (under the brand name Daytrana), similar to those used for nicotine replacement therapy. Brand names include Concerta, MediKinet, Equasym XL, Metadate, Methylin, and MPH

Concerta tablets are marked with the letters "ALZA" and followed by: "18", "27", "36", or "54", relating to the mg dosage strength. Approximately 22% of the Concerta dose is immediate release, and the remaining 78% of the dose is evenly released over 10–12 hours post ingestion.

Ritalin LA capsules are marked with the letters "NVR" (abbrev.: Novartis) and followed by: "R20", "R30", or "R40", depending on the (mg) dosage strength. The capsules contain two types of beads; 50% of the beads are immediate release, and the other 50% of the beads are enteric-coated, designed to give a second delayed release approximately 5 hours post ingestion.

Metadate CD capsules contain two types of beads; 30% of the beads are immediate release, and the other 70% of the beads are evenly sustained release over approximately 8 hours.

Controversy

Main article: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder controversiesMethylphenidate has been the subject of controversy in relation to its use in the treatment of ADHD. One such criticism is prescribing psychostimulants medication to children to reduce ADHD symptoms. Calls have been made that methylphenidate be severely restricted in its use. The pharmacological effects of methylphenidate resemble closely those of cocaine and amphetamines, which is the desired effect in the treatment of ADHD, and how methylphenidate works.

The abuse pattern of methylphenidate is very similar to heroin and amphetamines. A 2002 study showed that rats treated with methylphenidate are more receptive to the reinforcing effects of cocaine. The contention that methylphenidate acts as a gateway drug has been discredited by multiple sources, according to which abuse is statistically very low and "stimulant therapy in childhood does not increase the risk for subsequent drug and alcohol abuse disorders later in life".

Another controversial idea surrounding ADHD is that a group of ADHD children have, in general, healthy brains with no gross neurological deficits. This concept, however, is seen as outdated by a few scientists in current medical research, who claim they can identify an ADHD child's brain using CT brain scans, and how methylphenidate interacts with it. The problem herein is that no control was used in the cited research that would differentiate an ADHD child's brain from one that had been treated with stimulants beforehand.

Treatment of ADHD by way of Methylphenidate has led to legal actions including malpractice suits regarding informed consent, inadequate information on side effects, misdiagnosis, and coercive use of medications by school systems. In the U.S. and the United Kingdom, it is approved for use in children and adolescents. The FDA recently approved the use of methylphenidate for use in treating adult ADHD. Methylphenidate has been approved for adult use in the treatment of narcolepsy.

Anti-Ritalin political campaign

In 2002, Neil Bush told the New York Post that he "endured his own Ritalin hell seven years ago when educators in a Houston private school diagnosed his son, Pierce, (then) 16, with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and pushed medication."

In a September 26, 2002, episode of CNN Interview, Bush told Connie Chung:

You know, we have a knee-jerk reaction in this education system where, if the kid doesn't perform well, then the reaction is to try to assign a label. The label is followed by a drug. The drug allows the kid to sit cooperatively, to pay attention, to focus in school.

Neil Bush spent years researching the issue and found that "the educators were wrong" about his son. "There is a systemic problem in this country, where schools are often forcing parents to turn to Ritalin," he said. "It's obvious to me that we have a crisis." Also that year, Bush testified before a hearing of the United States Congress to speak out against over-medicating children for learning disorders.

He has suggested that many parents believe the ADD and ADHD diagnoses and subsequent medicating of their children because it explains why they aren't doing well in school, saying "it's the system that is failing to engage children in the classroom. My heart goes out to any parents who are being led to believe their kids have a disorder or are disabled."

Neil Bush (along with filmmaker Michael Moore) is credited in the cast of a 2005 documentary called The Drugging of Our Children directed by Gary Null. In the film's trailer Bush says: "Just because it is easy to drug a kid and get them to be compliant doesn't make it right to do it".

References

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- "Ritalin & Cocaine: The Connection and the Controversy". Learn.genetics.utah.edu. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- Mary Ann Boyd (2005). Psychiatric nursing: contemporary practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 160–. ISBN 9780781749169. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Peter Doskoch (2002). "Why isn't methylphenidate more addictive?". NeuroPsychiatry Rev. 3 (1): 19. Archived from the original on 2009-03-30.

- Markowitz JS, Logan BK, Diamond F, Patrick KS (1999). "Detection of the novel metabolite ethylphenidate after methylphenidate overdose with alcohol coingestion". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (4): 362–6. doi:10.1097/00004714-199908000-00013. PMID 10440465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Steele M, Weiss M, Swanson J, Wang J, Prinzo RS, Binder CE (2006). "A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of OROS-methylphenidate compared to usual care with immediate-release methylphenidate in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder" (PDF). Can J Clin Pharmacol. 13 (1): e50–62. PMID 16456216.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gilmore A, Milne R (2001). "Methylphenidate in children with hyperactivity: review and cost-utility analysis". Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 10 (2): 85–94. doi:10.1002/pds.564. PMID 11499858.

- Mott TF, Leach L, Johnson L (2004). "Clinical inquiries. Is methylphenidate useful for treating adolescents with ADHD?". The Journal of Family Practice. 53 (8): 659–61. PMID 15298843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vitiello B (2001). "Psychopharmacology for young children: clinical needs and research opportunities". Pediatrics. 108 (4): 983–9. doi:10.1542/peds.108.4.983. PMID 11581454.

- Hermens DF, Rowe DL, Gordon E, Williams LM (2006). "Integrative neuroscience approach to predict ADHD stimulant response". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 6 (5): 753–63. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.5.753. PMID 16734523.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fone KC, Nutt DJ (2005). "Stimulants: use and abuse in the treatment of ADD". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 5 (1): 87–93. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2004.10.001. PMID 15661631.

- Capp PK, Pearl PL, Conlon C (2005). "Methylphenidate HCl: therapy for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Expert Rev Neurother. 5 (3): 325–31. doi:10.1586/14737175.5.3.325. PMID 15938665.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Greenfield B, Hechman L (2005). "Treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults". Expert Rev Neurother. 5 (1): 107–21. doi:10.1586/14737175.5.1.107. PMID 15853481.

- Swanson JM, Cantwell D, Lerner M, McBurnett K, Hanna G (1991). "Effects of stimulant medication on learning in children with ADHD". J Learn Disabil. 24 (4): 219–30, 255. doi:10.1177/002221949102400406. PMID 1875157.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Joseph Biederman, MD, Timothy Wilens, MD, Eric Mick, ScDv, Thomas Spencer, MD, Stephen V. Faraone, PhD (1999). "Pharmacotherapy of Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Reduces Risk for Substance Use Disorder". Pediatrics. 104 (2): 20ff.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Schachter HM, Pham B, King J, Langford S, Moher D (2001). "How efficacious and safe is short-acting methylphenidate for the treatment of attention-deficit disorder in children and adolescents? A meta-analysis". CMAJ. 165 (11): 1475–88. PMC 81663. PMID 11762571.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Morgan AM (1988). "Use of stimulant medications in children". Am Fam Physician. 38 (4): 197–202. PMID 3051976.

- Stevenson RD, Wolraich ML (1989). "Stimulant medication therapy in the treatment of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 36 (5): 1183–97. PMID 2677938.

- ^ Kidd PM (2000). "Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children: rationale for its integrative management" (PDF). Altern Med Rev. 5 (5): 402–28. PMID 11056411.

- Fry JM (1998). "Treatment modalities for narcolepsy". Neurology. 50 (2 Suppl 1): S43–8. PMID 9484423.

- Mitler MM (1994). "Evaluation of treatment with stimulants in narcolepsy". Sleep. 17 (8 Suppl): S103–6. PMID 7701190.

- Kraus MF, Burch EA (1992). "Methylphenidate hydrochloride as an antidepressant: controversy, case studies, and review". South. Med. J. 85 (10): 985–91. doi:10.1097/00007611-199210000-00012. PMID 1411740.

- Rozans M, Dreisbach A, Lertora JJ, Kahn MJ (2002). "Palliative uses of methylphenidate in patients with cancer: a review". J. Clin. Oncol. 20 (1): 335–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.1.335. PMID 11773187.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leonard BE, McCartan D, White J, King DJ (2004). "Methylphenidate: a review of its neuropharmacological, neuropsychological and adverse clinical effects". Hum Psychopharmacol. 19 (3): 151–80. doi:10.1002/hup.579. PMID 15079851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Satel SL, Nelson JC (1989). "Stimulants in the treatment of depression: a critical overview". J Clin Psychiatry. 50 (7): 241–9. PMID 2567730.

- Schweitzer I, Tuckwell V, Johnson G (1997). "A review of the use of augmentation therapy for the treatment of resistant depression: implications for the clinician". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 31 (3): 340–52. doi:10.3109/00048679709073843. PMID 9226079.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Elkashef A, Vocci F, Hanson G, White J, Wickes W, Tiihonen J (2008). "Pharmacotherapy of methamphetamine addiction: an update". Substance Abuse. 29 (3): 31–49. doi:10.1080/08897070802218554. PMC 2597382. PMID 19042205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grabowski J, Roache JD, Schmitz JM, Rhoades H, Creson D, Korszun A (1997). "Replacement medication for cocaine dependence: methylphenidate". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 17 (6): 485–8. doi:10.1097/00004714-199712000-00008. PMID 9408812.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gorelick DA, Gardner EL, Xi ZX (2004). "Agents in development for the management of cocaine abuse". Drugs. 64 (14): 1547–73. doi:10.2165/00003495-200464140-00004. PMID 15233592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Karila L, Gorelick D, Weinstein A; et al. (2008). "New treatments for cocaine dependence: a focused review". Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11 (3): 425–38. doi:10.1017/S1461145707008097. PMID 17927843.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "NIDA InfoFacts: Understanding Drug Abuse and Addiction" (PDF). 2008.

- Shearer J (2008). "The principles of agonist pharmacotherapy for psychostimulant dependence". Drug Alcohol Rev. 27 (3): 301–8. doi:10.1080/09595230801927372. PMID 18368612.

- Kaufman, Marc J., Cocaine-Induced Cerebral Vasoconstriction Detected in Humans With Magnetic Resonance Angiography (PDF)

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Russo KE, Hall W, Chi OZ, Sinha AK, Weiss HR (1991). "Effect of amphetamine on cerebral blood flow and capillary perfusion". Brain Res. 542 (1): 43–8. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(91)90995-8. PMID 1905179.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Aman MG, Langworthy KS (2000). "Pharmacotherapy for hyperactivity in children with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders". J Autism Dev Disord. 30 (5): 451–9. doi:10.1023/A:1005559725475. PMID 11098883.

- Jahromi LB, Kasari CL, McCracken JT; et al. (2009). "Positive effects of methylphenidate on social communication and self-regulation in children with pervasive developmental disorders and hyperactivity". J Autism Dev Disord. 39 (3): 395–404. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0636-9. PMID 18752063.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grund T, Lehmann K, Bock N, Rothenberger A, Teuchert-Noodt G (2006). "Influence of methylphenidate on brain development—an update of recent animal experiments". Behav Brain Funct. 2: 2. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-2-2. PMC 1363724. PMID 16403217.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Sagvolden T, Sergeant JA (1998). "Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder—from brain dysfunctions to behaviour". Behav. Brain Res. 94 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(97)00164-2. PMID 9708834.

- Methylphenidate Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. Drugs.com. Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Humphreys C, Garcia-Bournissen F, Ito S, Koren G (2007). "Exposure to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medications during pregnancy". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (7): 1153–5. PMC 1949295. PMID 17872810.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kaufman, David Myland; Heinonen, Olli P.; Slone, Dennis; Shapiro, Samuel (1977). Birth defects and drugs in pregnancy. Littleton, Mass: Publishing Sciences Group. ISBN 0-88416-034-3. OCLC 2387745.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yaffe, Sumner J.; Briggs, Gerald G.; Freeman, Roger Anthony (2005). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5651-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gordon N (1999). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: possible causes and treatment". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 53 (7): 524–8. PMID 10692738.

- King S, Griffin S, Hodges Z; et al. (2006). "A systematic review and economic model of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of methylphenidate, dexamfetamine and atomoxetine for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents". Health Technol Assess. 10 (23): iii–iv, xiii–146. PMID 16796929.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gonzalez de Dios J, Cardó E, Servera M (2006). "". Rev Neurol (in Spanish; Castilian). 43 (12): 705–14. PMID 17160919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - – Ritalin Side Effects. Drugs.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- Jaanus SD (1992). "Ocular side-effects of selected systemic drugs". Optom Clin. 2 (4): 73–96. PMID 1363080.

- Rao JK, Julius JR, Breen TJ, Blethen SL (1998). "Response to growth hormone in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of methylphenidate and pemoline therapy". Pediatrics. 102 (2 Pt 3): 497–500. PMID 9685452.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Harding M, O'Donnell D, Faraone SV, Wilens TE (1996). "Growth deficits in ADHD children revisited: evidence for disorder-associated growth delays?". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 35 (11): 1460–9. doi:10.1097/00004583-199611000-00014. PMID 8936912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Klein RG, Mannuzza S (1988). "Hyperactive boys almost grown up. III. Methylphenidate effects on ultimate height". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 45 (12): 1131–4. PMID 3058089.

- Wilens T, McBurnett K, Stein M, Lerner M, Spencer T, Wolraich M (2005). "ADHD treatment with once-daily OROS methylphenidate: final results from a long-term open-label study". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 44 (10): 1015–23. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000173291.28688.e7. PMID 16175106.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Teo SK, San RH, Wagner VO; et al. (2003). "D-Methylphenidate is non-genotoxic in in vitro and in vivo assays". Mutat. Res. 537 (1): 67–79. doi:10.1016/S1383-5718(03)00053-6. PMID 12742508.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Walitza, Susanne; Werner, B; Romanos, M; Warnke, A; Gerlach, M; Stopper, H; Walitza, Susanne; et al. (2007). "Does Methylphenidate Cause a Cytogenetic Effect in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (6): 936–940. doi:10.1289/ehp.9866. PMC 1892117. PMID 17589603.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author8=(help); Missing|author7=(help) - Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F (2000). "Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers". JAMA. 283 (8): 1025–30. doi:10.1001/jama.283.8.1025. PMID 10697062.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Minutes of the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee. March 22, 2006.

- "FDA may reject safety warning for ADHD drugs". New Scientist. 18 February 2006

- Minutes of the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee, March 22, 2006

- Auger RR, Goodman SH, Silber MH, Krahn LE, Pankratz VS, Slocumb NL (2005). "Risks of high-dose stimulants in the treatment of disorders of excessive somnolence: a case-control study". Sleep. 28 (6): 667–72. PMID 16477952.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "ADHD & Women's Health – Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder National Women's Health Report". 2003. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

Although methylphenidate is perhaps one of the best-studied drugs available, with thousands of studies attesting to its long-term that finds the numbers of children taking the drug skyrocketing in recent years.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Edmund J. S. Sonuga-Barke, Margaret Thompson, Howard Abikoff, Rachel Klein, Laurie Miller Brotman. "Nonpharmacological Interventions for Preschoolers With ADHD: The Case for Specialized Parent Training" (PDF). Infants & Young Children. 19 (2): 142–153. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

While most recent studies suggest that methylphenidate is relatively well-tolerated by young children, some suggest that side-effects might be more marked in preschoolers than in school-aged children (Firestone, Musten, Pisterman, Mercer, & Bennett, 1998). Furthermore, some researchers have argued that there is the potential for negative long-term effects on the developing brains of young children chronically medicated (Moll, Rothenberger, Ruther, & Huther, 2002).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ashton H, Gallagher P, Moore B (2006). "The adult psychiatrist's dilemma: psychostimulant use in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 20 (5): 602–10. doi:10.1177/0269881106061710. PMID 16478756.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kociancic T, Reed MD, Findling RL (2004). "Evaluation of risks associated with short- and long-term psychostimulant therapy for treatment of ADHD in children". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 3 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1517/eods.3.2.93.27337. PMID 15006715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Ritalin & Ritalin-SR Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis. 2007.

- Cherland E, Fitzpatrick R (1999). "Psychotic side effects of psychostimulants: a 5-year review" (PDF). Can J Psychiatry. 44 (8): 811–3. PMID 10566114.

- Kimko HC, Cross JT, Abernethy DR (1999). "Pharmacokinetics and clinical effectiveness of methylphenidate". Clin Pharmacokinet. 37 (6): 457–70. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937060-00002. PMID 10628897.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dafny N, Yang PB (2006). "The role of age, genotype, sex, and route of acute and chronic administration of methylphenidate: a review of its locomotor effects". Brain Research Bulletin. 68 (6): 393–405. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.10.005. PMID 16459193.

- Ross RG (2006). "Psychotic and manic-like symptoms during stimulant treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Am J Psychiatry. 163 (7): 1149–52. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1149. PMID 16816217.

- DelBello MP, Soutullo CA, Hendricks W, Niemeier RT, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM (2001). "Prior stimulant treatment in adolescents with bipolar disorder: association with age at onset". Bipolar Disord. 3 (2): 53–7. doi:10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030201.x. PMID 11333062.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Soutullo CA, DelBello MP, Ochsner JE; et al. (2002). "Severity of bipolarity in hospitalized manic adolescents with history of stimulant or antidepressant treatment". J Affect Disord. 70 (3): 323–7. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00336-6. PMID 12128245.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kuczenski R, Segal DS (2005). "Stimulant actions in rodents: implications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment and potential substance abuse". Biol. Psychiatry. 57 (11): 1391–6. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.036. PMID 15950013.

- ^ Patrick KS, Straughn AB, Perkins JS, González MA (2009). "Evolution of stimulants to treat ADHD: transdermal methylphenidate". Human Psychopharmacology. 24 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1002/hup.992. PMC 2629554. PMID 19051222.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leith NJ, Barrett RJ (1981). "Self-stimulation and amphetamine: tolerance to d and l isomers and cross tolerance to cocaine and methylphenidate". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 74 (1): 23–8. doi:10.1007/BF00431751. PMID 6791199.

- Cohen D, Leo J, Stanton T; et al. (2002). "A boy who stops taking stimulants for "ADHD": commentaries on a Pediatrics case study". Ethical Hum Sci Serv. 4 (3): 189–209. PMID 15278983.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Schwartz RH, Rushton HG (2004). "Stuttering priapism associated with withdrawal from sustained-release methylphenidate". J. Pediatr. 144 (5): 675–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.039. PMID 15127013.

- Garland EJ (1998). "Pharmacotherapy of adolescent attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: challenges, choices and caveats". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 12 (4): 385–95. doi:10.1177/026988119801200410. PMID 10065914.

- Nolan EE, Gadow KD, Sprafkin J (1999). "Stimulant medication withdrawal during long-term therapy in children with comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and chronic multiple tic disorder". Pediatrics. 103 (4 Pt 1): 730–7. doi:10.1542/peds.103.4.730. PMID 10103294.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smucker WD, Hedayat M (2001). "Evaluation and treatment of ADHD". Am Fam Physician. 64 (5): 817–29. PMID 11563573.

- Rosenfeld AA (1979). "Depression and psychotic regression following prolonged methylphenidate use and withdrawal: case report". Am J Psychiatry. 136 (2): 226–8. PMID 760559.

- Riccio CA, Waldrop JJ, Reynolds CR, Lowe P (2001). "Effects of stimulants on the continuous performance test (CPT): implications for CPT use and interpretation". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 13 (3): 326–35. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13.3.326. PMID 11514638.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Roberts SM, DeMott RP, James RC (1997). "Adrenergic modulation of hepatotoxicity". Drug Metab. Rev. 29 (1–2): 329–53. doi:10.3109/03602539709037587. PMID 9187524.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Marotta PJ, Roberts EA (1998). "Pemoline hepatotoxicity in children". The Journal of Pediatrics. 132 (5): 894–7. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70329-4. PMID 9602211.

- Patrick KS, González MA, Straughn AB, Markowitz JS (2005). "New methylphenidate formulations for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2 (1): 121–43. doi:10.1517/17425247.2.1.121. PMID 16296740.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Markowitz JS, DeVane CL, Boulton DW; et al. (2000). "Ethylphenidate formation in human subjects after the administration of a single dose of methylphenidate and ethanol". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 28 (6): 620–4. PMID 10820132.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Patrick KS, Williard RL, VanWert AL, Dowd JJ, Oatis JE, Middaugh LD (2005). "Synthesis and pharmacology of ethylphenidate enantiomers: the human transesterification metabolite of methylphenidate and ethanol". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 48 (8): 2876–81. doi:10.1021/jm0490989. PMID 15828826.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Williard RL, Middaugh LD, Zhu HJ, Patrick KS (2007). "Methylphenidate and its ethanol transesterification metabolite ethylphenidate: brain disposition, monoamine transporters and motor activity". Behavioural Pharmacology. 18 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280143226. PMID 17218796.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tan M, Appleton R (2005). "Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, methylphenidate, and epilepsy". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 90 (1): 57–9. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.048504. PMC 1720074. PMID 15613514.

- Zhu J, Reith ME (2008). "Role of the dopamine transporter in the action of psychostimulants, nicotine, and other drugs of abuse". CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets. 7 (5): 393–409. doi:10.2174/187152708786927877. PMC 3133725. PMID 19128199.

- Volkow ND, Swanson JM (2003). "Variables that affect the clinical use and abuse of methylphenidate in the treatment of ADHD". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1909–18. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1909. PMID 14594733.

- ^ Klein-Schwartz W (2002). "Abuse and toxicity of methylphenidate". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 14 (2): 219–23. doi:10.1097/00008480-200204000-00013. PMID 11981294.

- ^ Stern EJ, Frank MS, Schmutz JF, Glenny RW, Schmidt RA, Godwin JD (1994). "Panlobular pulmonary emphysema caused by i.v. injection of methylphenidate (Ritalin): findings on chest radiographs and CT scans". American Journal of Roentgenology. 162 (3): 555–60. PMID 8109495.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Arria AM, Wish ED (2006). "Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants among students". Pediatric Annals. 35 (8): 565–71. PMC 3168781. PMID 16986451.

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Gatley SJ; et al. (1999). "Comparable changes in synaptic dopamine induced by methylphenidate and by cocaine in the baboon brain". Synapse. 31 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199901)31:1<59::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 10025684.

Almost indistinguishable from that induced by i.v. cocaine

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Gatley SJ, Logan J (2001). "Cocaine: PET studies of cocaine pharmacokinetics, dopamine transporter availability and dopamine transporter occupancy". Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 28 (5): 561–72. doi:10.1016/S0969-8051(01)00211-6. PMID 11516700.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.udel.edu/chemo/teaching/CHEM465/SitesF02/Prop26b/Rit%20Page4.html Pretreatment with methylphenidate sensitizes rats to the reinforcing effects of cocaine

- Midgely, Carol (February 21, 2003). "Kiddie coke: A new peril in the playground". London: The Times. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Harris J (2009). "Is it acceptable for people to take methylphenidate to enhance performance? Yes". BMJ. 338: b1955. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1955. PMID 19541705.

- Chatterjee A (2009). "Is it acceptable for people to take methylphenidate to enhance performance? No". BMJ. 338: b1956. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1956. PMID 19541706.

- "Ritalin backed as brain-booster". BBC News. 19 June 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Davies, Caroline (21 February 2010). "Universities told to consider dope tests as student use of 'smart drugs' soars". London: The Observer. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ Scharman EJ, Erdman AR, Cobaugh DJ; et al. (2007). "Methylphenidate poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management". Clinical Toxicology. 45 (7): 737–52. doi:10.1080/15563650701665175. PMID 18058301.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 9th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA, 2011, pp. 1091–93.

- ^ Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A (2005). "Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review" (PDF). Prog. Neurobiol. 75 (6): 406–33. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. PMID 15955613.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Iversen L (2006). "Neurotransmitter transporters and their impact on the development of psychopharmacology". British Journal of Pharmacology. 147 (Suppl 1): S82–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706428. PMC 1760736. PMID 16402124.

- ^ Viggiano D, Vallone D, Sadile A (2004). "Dysfunctions in dopamine systems and ADHD: evidence from animals and modeling". Neural Plasticity. 11 (1–2): 102, 106–107. doi:10.1155/NP.2004.97. PMC 2565441. PMID 15303308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)Full-text - Novartis: Focalin XR Overview

- Focalin XR – Full Prescribing Information. Novartis.

- SPC Concerta XL 18 mg – 36 mg prolonged release tablets last updated on the eMC: 05/11/2010

- ^ Heal DJ, Pierce DM (2006). "Methylphenidate and its isomers: their role in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder using a transdermal delivery system". CNS Drugs. 20 (9): 713–38. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620090-00002. PMID 16953648.

- Markowitz JS, DeVane CL, Pestreich LK, Patrick KS, Muniz R (2006). "A comprehensive in vitro screening of d-, l-, and dl-threo-methylphenidate: an exploratory study". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 16 (6): 687–98. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.16.687. PMID 17201613.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Ding YS (2005). "Imaging the effects of methylphenidate on brain dopamine: new model on its therapeutic actions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Biol. Psychiatry. 57 (11): 1410–5. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.006. PMID 15950015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wolraich ML, Doffing MA (2004). "Pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with methylphenidate". CNS Drugs. 18 (4): 243–50. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418040-00004. PMID 15015904.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12468013, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12468013instead. - Dutta AK, Zhang S, Kolhatkar R, Reith ME (2003). "Dopamine transporter as target for drug development of cocaine dependence medications". European Journal of Pharmacology. 479 (1–3): 93–106. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.060. PMID 14612141.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS; et al. (1998). "Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 155 (10): 1325–31. PMID 9766762.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG (2001). "Genetics of childhood disorders: XXIV. ADHD, part 8: hyperdopaminergic mice as an animal model of ADHD". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 40 (3): 380–2. doi:10.1097/00004583-200103000-00020. PMID 11288782.

- Koelega HS (1993). "Stimulant drugs and vigilance performance: a review". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 111 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1007/BF02257400. PMID 7870923.

- Rosack Jim (2 January 2004). "Brain Scans Reveal Physiology of ADHD". Psychiatric News. 39 (1): 26.

- Tomasi D, Volkow ND; et al. (14 February 2011). "Methylphenidate enhances brain activation and deactivation responses to visual attention and working memory tasks in healthy controls". Neuroimage. 54 (4): 3101–3110. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.060. PMC 3020254. PMID 21029780.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ; et al. (2008). Hashimoto, Kenji (ed.). "Methylphenidate decreased the amount of glucose needed by the brain to perform a cognitive task". PLoS ONE. 3 (4): e2017. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2017V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002017. PMC 2291196. PMID 18414677.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW (2008). "Cognition-enhancing doses of methylphenidate preferentially increase prefrontal cortex neuronal responsiveness". Biol. Psychiatry. 64 (7): 626–35. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.037. PMC 2603602. PMID 18585681.

- "New Brookhaven Lab Study Shows How Ritalin Works".

- ^ Gottlieb, Scott (2001). "Therapeutic Doses of Oral Methylphenidate Significantly Increase Extracellular Dopamine in the Human Brain Methylphenidate works by increasing dopamine levels". British Medical Journal.

- "Therapeutic Doses of Oral Methylphenidate Significantly Increase Extracellular Dopamine in the Human Brain".

- Kathie Keeler (March 3, 2009). "Addiction–The Hijacked Brain". TGCoy.

- "The Role of Dopamine and Norepinephrine in Depression".

- Volkow, ND; Fowler, JS; Wang, GJ; Telang, F; Logan, J; Wong, C; Ma, J; Pradhan, K; Benveniste, H (2008). "Methylphenidate Decreased the Amount of Glucose Needed by the Brain to Perform a Cognitive Task". PloS one. 3 (4): e2017. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002017. PMC 2291196. PMID 18414677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - "Dopamine". ISCID Encyclopedia of Science and Philosophy.

- Froimowitz M, Patrick KS, Cody V (1995). "Conformational analysis of methylphenidate and its structural relationship to other dopamine reuptake blockers such as CFT". Pharmaceutical Research. 12 (10): 1430–4. doi:10.1023/A:1016262815984. PMID 8584475.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Prashad, M (2001). "Approaches to the Preparation of Enantiomerically Pure (2R,2′R)-(+)-threo-Methylphenidate Hydrochloride" (PDF). Adv. Synth. Catal. 343 (5): 379–92. doi:10.1002/1615-4169(200107)343:5<379::AID-ADSC379>3.0.CO;2-4.

- ^ Singh, Satendra (2000). "Chemistry, Design, and Structure-Activity Relationship of Cocaine Antagonists" (PDF). Chem. Rev. 100 (3): 925–1024 (1008). doi:10.1021/cr9700538. PMID 11749256.

- Panizzon, Leandro (1944). "La preparazione di piridil- e piperidil-arilacetonitrili e di alcuni prodotti di trasformazione (Parte Ia)". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 27: 1748–56. doi:10.1002/hlca.194402701222.

- Meier, R; Gross, F; Tripod, J (1954). "Ritalin, a new synthetic compound with specific analeptic components". Klinische Wochenschrift. 32 (19–20): 445–50. PMID 13164273.

- Myers, Richard L (2007-08). The 100 most important chemical compounds: a reference guide By Richard L. Myers. ISBN 9780313337581. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Leandro Panizzon et al Pyridine and piperdjine compounds U.S. patent 2,507,631 Issue date: May 16, 1950

- Rudolf Rouietscji et al Process for the conversion of U.S. patent 2,838,519 Issue date: Jun 10, 1958

- Rudolf Rouietscji et al Process for the conversion of U.S. patent 2,957,880 Issue date: Oct 25, 1960

- Terrance Woodworth (May 16, 2000). "DEA Congressional Testimony". Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- Newly Approved Drug Therapies (637) Concerta, Alza. CenterWatch. Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Template:PDFlink 23rd edition. August 2003. International Narcotics Board, Vienna International Centre. Retrieved 2 March 2006.

- Concerta for Kids with ADHD. Pediatrics.about.com (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Concerta (Methylphenidate Extended-Release Tablets) Drug Information: User Reviews, Side Effects, Drug Interactions and Dosage at RxList. Rxlist.com. Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Ritalin LA® (methylphenidate hydrochloride) extended-release capsules, Novartis

- Metadate CD. Adhd.emedtv.com. Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Lakhan SE, Hagger-Johnson GE (2007). "The impact of prescribed psychotropics on youth". Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health. 3 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-3-21. PMC 2100041. PMID 17949504.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Drug Enforcement Administration, Greene, S.H., Response to CHADD petition concerning Ritalin, 1995, August 7. Washington, DC: DEA, U.S. Department of Justice.

- The Neurobiology of ADHD, ADHD.org.nz

- ^ Volkow ND; et al. (2001). "Therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate significantly increase extracellular dopamine in the human brain". The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 21 (2): RC121. PMID 11160455.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - New Research Helps Explain Ritalin's Low Abuse Potential When Taken As Prescribed – 09/29/1998. Nih.gov. Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Wilens TE, Faraone SV, Biederman J, Gunawardene S (2003). "Does stimulant therapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder beget later substance abuse? A meta-analytic review of the literature". Pediatrics. 111 (1): 179–85. doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.179. PMID 12509574.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K (2003). "Does the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with stimulants contribute to drug use/abuse? A 13-year prospective study". Pediatrics. 111 (1): 97–109. doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.97. PMID 12509561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stimulant ADHD Medications: Methylphenidate and Amphetamines – InfoFacts – NIDA. Drugabuse.gov. Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Weinberg WA, Brumback RA (1992). "The myth of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder: symptoms resulting from multiple causes". J. Child Neurol. 7 (4): 431–45, discussion 446–61. doi:10.1177/088307389200700420. PMID 1469255.

- Brain Scans Reveal Physiology of ADHD — Psychiatric News. Pn.psychiatryonline.org (2004-01-02). Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Ouellette EM (1991). "Legal issues in the treatment of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Child Neurology. 6 Suppl: S68–75. PMID 2002217.

- FDA Approves CONCERTA® (methylphenidate HCI) Extended-release Tablets for Treatment of ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) in Adults, Johnson & Johnson, News Release, June 27, 2008

- Ritalin for Adults. Adhd.emedtv.com (2007-03-06). Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) – Treatment – NHS Choices. Nhs.uk (2010-05-19). Retrieved on 2011-04-30.

- Interview With Neil Bush; Interview With Magic Johnson. Transcripts.cnn.com. September 26, 2002. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- Ritalin Roundup Continues – September 2002 Education Reporter. Eagleforum.org (2002-09-25). Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- The Drugging of Our Children (2005) (V). Imdb.com (2009-05-01). Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- Film Detail. Ostrowandcompany.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

External links

- Template:DMOZ

- Department of Energy September 29, 1998 press release on Ritalin at Brookhaven National Laboratory

- Erowid methylphenidate vault

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Methylphenidate

| Stimulants | |

|---|---|

| Adamantanes | |

| Adenosine antagonists | |

| Alkylamines | |

| Ampakines | |

| Arylcyclohexylamines | |

| Benzazepines | |

| Cathinones |

|

| Cholinergics |

|

| Convulsants | |

| Eugeroics | |

| Oxazolines | |

| Phenethylamines |

|

| Phenylmorpholines | |

| Piperazines | |

| Piperidines |

|

| Pyrrolidines | |

| Racetams | |

| Tropanes |

|

| Tryptamines | |

| Others |

|

| ATC code: N06B | |

| ADHD pharmacotherapies | |

|---|---|

| CNSTooltip central nervous system stimulants | |

| Non-classical CNS stimulants | |

| α2-adrenoceptor agonists | |

| Antidepressants | |

| Miscellaneous/others | |

| Related articles |

|

| Adrenergic receptor modulators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 |

| ||||

| α2 |

| ||||

| β |

| ||||

| Dopamine receptor modulators | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1-like |

| ||||||

| D2-like |

| ||||||

| Phenethylamines | |

|---|---|

| Phenethylamines |

|

| Amphetamines |

|

| Phentermines |

|

| Cathinones |

|

| Phenylisobutylamines | |

| Phenylalkylpyrrolidines | |

| Catecholamines (and close relatives) |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA

Categories: