Molecular structure Molecular structure | |

A volumetric flask of a methylene blue solution A volumetric flask of a methylene blue solution | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Urelene blue, Provayblue, Proveblue, others |

| Other names | CI 52015, basic blue 9 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 5–24 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.469 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H18ClN3S |

| Molar mass | 319.85 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Methylthioninium chloride, commonly called methylene blue, is a salt used as a dye and as a medication. As a medication, it is mainly used to treat methemoglobinemia by chemically reducing the ferric iron in hemoglobin to ferrous iron. Specifically, it is used to treat methemoglobin levels that are greater than 30% or in which there are symptoms despite oxygen therapy. It has previously been used for treating cyanide poisoning and urinary tract infections, but this use is no longer recommended.

Methylene blue is typically given by injection into a vein. Common side effects include headache, nausea, and vomiting. While use during pregnancy may harm the fetus, not using it in methemoglobinemia is likely more dangerous.

Methylene blue was first prepared in 1876, by Heinrich Caro. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.

Uses

Methemoglobinemia

Methylene blue is employed as a medication for the treatment of methemoglobinemia, which can arise from ingestion of certain pharmaceuticals, toxins, or broad beans in those susceptible. Normally, through the NADH- or NADPH-dependent methemoglobin reductase enzymes, methemoglobin is reduced back to hemoglobin. When large amounts of methemoglobin occur secondary to toxins, methemoglobin reductases are overwhelmed. Methylene blue, when injected intravenously as an antidote, is itself first reduced to leucomethylene blue, which then reduces the heme group from methemoglobin to hemoglobin. Methylene blue can reduce the half life of methemoglobin from hours to minutes. At high doses, however, methylene blue actually induces methemoglobinemia, reversing this pathway.

Methylphen

This section is an excerpt from Hyoscyamine/hexamethylenetetramine/phenyl salicylate/methylene blue/benzoic acid. Hyoscyamine/hexamethylenetetramine/phenyl salicylate/methylene blue/benzoic acid is a combination drug used to treat pain caused by urinary tract infections and spasms of the urinary tract. It is currently sold under multiple brand names in the US. It was formerly sold as Prosed/DS, but this particular brand name was discontinued.Cyanide poisoning

Since its reduction potential is similar to that of oxygen and can be reduced by components of the electron transport chain, large doses of methylene blue are sometimes used as an antidote to potassium cyanide poisoning, a method first successfully tested in 1933 by Matilda Moldenhauer Brooks in San Francisco, although first demonstrated by Bo Sahlin of Lund University, in 1926.

Dye or stain

Methylene blue is used in endoscopic polypectomy as an adjunct to saline or epinephrine, and is used for injection into the submucosa around the polyp to be removed. This allows the submucosal tissue plane to be identified after the polyp is removed, which is useful in determining if more tissue needs to be removed, or if there has been a high risk for perforation. Methylene blue is also used as a dye in chromoendoscopy, and is sprayed onto the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract in order to identify dysplasia, or pre-cancerous lesions. Intravenously injected methylene blue is readily released into the urine and thus can be used to test the urinary tract for leaks or fistulas.

In surgeries such as sentinel lymph node dissections, methylene blue can be used to visually trace the lymphatic drainage of tested tissues. Similarly, methylene blue is added to bone cement in orthopedic operations to provide easy discrimination between native bone and cement. Additionally, methylene blue accelerates the hardening of bone cement, increasing the speed at which bone cement can be effectively applied. Methylene blue is used as an aid to visualisation/orientation in a number of medical devices, including a Surgical sealant film, TissuePatch. In fistulas and pilonidal sinuses it is used to identify the tract for complete excision. It can also be used during gastrointestinal surgeries (such as bowel resection or gastric bypass) to test for leaks.

It is sometimes used in cytopathology, in mixtures including Wright-Giemsa and Diff-Quik. It confers a blue color to both nuclei and cytoplasm, and makes the nuclei more visible. When methylene blue is "polychromed" (oxidized in solution or "ripened" by fungal metabolism, as originally noted in the thesis of Dr. D. L. Romanowsky in the 1890s), it gets serially demethylated and forms all the tri-, di-, mono- and non-methyl intermediates, which are Azure B, Azure A, Azure C, and thionine, respectively. This is the basis of the basophilic part of the spectrum of Romanowski-Giemsa effect. If only synthetic Azure B and Eosin Y is used, it may serve as a standardized Giemsa stain; but, without methylene blue, the normal neutrophilic granules tend to overstain and look like toxic granules. On the other hand, if methylene blue is used it might help to give the normal look of neutrophil granules and may also enhance the staining of nucleoli and polychromatophilic RBCs (reticulocytes).

A traditional application of methylene blue is the intravital or supravital staining of nerve fibers, an effect first described by Paul Ehrlich in 1887. A dilute solution of the dye is either injected into tissue or applied to small freshly removed pieces. The selective blue coloration develops with exposure to air (oxygen) and can be fixed by immersion of the stained specimen in an aqueous solution of ammonium molybdate. Vital methylene blue was formerly much used for examining the innervation of muscle, skin and internal organs. The mechanism of selective dye uptake is incompletely understood; vital staining of nerve fibers in skin is prevented by ouabain, a drug that inhibits the Na/K-ATPase of cell membranes.

Placebo

Methylene blue has been used as a placebo; physicians would tell their patients to expect their urine to change color and view this as a sign that their condition had improved. This same side effect makes methylene blue difficult to use in traditional placebo-controlled clinical studies, including those testing for its efficacy as a treatment.

Isobutyl nitrite toxicity

Isobutyl nitrite is one of the compounds used as poppers, an inhalant drug that induces a brief euphoria.

Isobutyl nitrite is known to cause methemoglobinemia. Severe methemoglobinemia may be treated with methylene blue.

Ifosfamide toxicity

Another use of methylene blue is to treat ifosfamide neurotoxicity. Methylene blue was first reported for treatment and prophylaxis of ifosfamide neuropsychiatric toxicity in 1994. A toxic metabolite of ifosfamide, chloroacetaldehyde (CAA), disrupts the mitochondrial respiratory chain, leading to an accumulation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogen (NADH). Methylene blue acts as an alternative electron acceptor, and reverses the NADH inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis while also inhibiting the transformation of chloroethylamine into chloroacetaldehyde, and inhibits multiple amine oxidase activities, preventing the formation of CAA. The dosing of methylene blue for treatment of ifosfamide neurotoxicity varies, depending upon its use simultaneously as an adjuvant in ifosfamide infusion, versus its use to reverse psychiatric symptoms that manifest after completion of an ifosfamide infusion. Reports suggest that methylene blue up to six doses a day have resulted in improvement of symptoms within 10 minutes to several days. Alternatively, it has been suggested that intravenous methylene blue every six hours for prophylaxis during ifosfamide treatment in people with history of ifosfamide neuropsychiatric toxicity. Prophylactic administration of methylene blue the day before initiation of ifosfamide, and three times daily during ifosfamide chemotherapy has been recommended to lower the occurrence of ifosfamide neurotoxicity.

Shock

It has also been used in septic shock and anaphylaxis.

Methylene blue consistently increases blood pressure in people with vasoplegic syndrome (redistributive shock), but has not been shown to improve delivery of oxygen to tissues or to decrease mortality.

Methylene blue has been used in calcium channel blocker toxicity as a rescue therapy for distributive shock unresponsive to first line agents. Evidence for its use in this circumstance is very poor and limited to a handful of case reports.

Side effects

| Cardiovascular | Central Nervous System | Dermatologic | Gastrointestinal | Genito-urinary | Hematologic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Hypertension • Precordial pain |

• Dizziness • Mental confusion • Headache • Fever |

• Staining of skin • Injection site necrosis (SC) |

• Fecal discoloration • Nausea • Vomiting • Abdominal pain |

• Discoloration of urine (doses over 80 μg) • Bladder irritation |

• Anemia |

Methylene blue is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) and, if infused intravenously at doses exceeding 5 mg/kg, may result in serotonin syndrome if combined with any selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or other serotonergic drugs (e.g., duloxetine, sibutramine, venlafaxine, clomipramine, imipramine).

It causes hemolytic anemia in carriers of the G6PD (favism) enzymatic deficiency.

Chemistry

Methylene blue is a formal derivative of phenothiazine. It is a dark green powder that yields a blue solution in water. The hydrated form has 3 molecules of water per unit of methylene blue.

Preparation

This compound is prepared by oxidation of 4-aminodimethylaniline in the presence of sodium thiosulfate to give the quinonediiminothiosulfonic acid, reaction with dimethylaniline, oxidation to the indamine, and cyclization to give the thiazine:

A green electrochemical procedure, using only dimethyl-4-phenylenediamine and sulfide ions has been proposed.

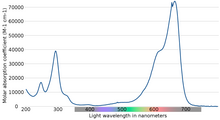

Light absorption properties

The maximum absorption of light is near 670 nm. The specifics of absorption depend on a number of factors, including protonation, adsorption to other materials, and metachromasy - the formation of dimers and higher-order aggregates depending on concentration and other interactions:

| Species | Absorption peak | Extinction coefficient (dm/mol·cm) |

|---|---|---|

| MB (solution) | 664 | 95000 |

| MBH2 (solution) | 741 | 76000 |

| (MB)2 (solution) | 605 | 132000 |

| (MB)3 (solution) | 580 | 110000 |

| MB (adsorbed on clay) | 673 | 116000 |

| MBH2 (adsorbed on clay) | 763 | 86000 |

| (MB)2 (adsorbed on clay) | 596 | 80000 |

| (MB)3 (adsorbed on clay) | 570 | 114000 |

Other uses

Redox indicator

Methylene blue is widely used as a redox indicator in analytical chemistry. Solutions of this substance are blue when in an oxidizing environment, but will turn colorless if exposed to a reducing agent. The redox properties can be seen in a classical demonstration of chemical kinetics in general chemistry, the "blue bottle" experiment. Typically, a solution is made of glucose (dextrose), methylene blue, and sodium hydroxide. Upon shaking the bottle, oxygen oxidizes methylene blue, and the solution turns blue. The dextrose will gradually reduce the methylene blue to its colorless, reduced form. Hence, when the dissolved dextrose is entirely consumed, the solution will turn blue again. The redox midpoint potential E0' is +0.01 V.

Peroxide generator

Methylene blue is also a photosensitizer used to create singlet oxygen when exposed to both oxygen and light. It is used in this regard to make organic peroxides by a Diels-Alder reaction which is spin forbidden with normal atmospheric triplet oxygen.

Sulfide analysis

The formation of methylene blue after the reaction of hydrogen sulfide with dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine and iron(III) at pH 0.4 – 0.7 is used to determine by photometric measurements sulfide concentration in the range 0.020 to 1.50 mg/L (20 ppb to 1.5 ppm). The test is very sensitive and the blue coloration developing upon contact of the reagents with dissolved H2S is stable for 60 min. Ready-to-use kits such as the Spectroquant sulfide test facilitate routine analyses. The methylene blue sulfide test is a convenient method often used in soil microbiology to quickly detect in water the metabolic activity of sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB). In this colorimetric test, methylene blue is a product formed by the reaction and not a reagent added to the system.

The addition of a strong reducing agent, such as ascorbic acid, to a sulfide-containing solution is sometimes used to prevent sulfide oxidation from atmospheric oxygen. Although it is certainly a sound precaution for the determination of sulfide with an ion selective electrode, it might however hamper the development of the blue color if the freshly formed methylene blue is also reduced, as described here above in the paragraph on redox indicator.

Test for milk freshness

Methylene blue is a dye behaving as a redox indicator that is commonly used in the food industry to test the freshness of milk and dairy products. A few drops of methylene blue solution added to a sample of milk should remain blue (oxidized form in the presence of enough dissolved O2), otherwise (discoloration caused by the reduction of methylene blue into its colorless reduced form) the dissolved O2 concentration in the milk sample is low indicating that the milk is not fresh (already abiotically oxidized by O2 whose concentration in solution decreases) or could be contaminated by bacteria also consuming the atmospheric O2 dissolved in the milk. In other words, aerobic conditions should prevail in fresh milk and methylene blue is simply used as an indicator of the dissolved oxygen remaining in the milk.

Water testing

Further information: MBAS assayThe adsorption of methylene blue serves as an indicator defining the adsorptive capacity of granular activated carbon in water filters. Adsorption of methylene blue is very similar to adsorption of pesticides from water, this quality makes methylene blue serve as a good predictor for filtration qualities of carbon. It is as well a quick method of comparing different batches of activated carbon of the same quality. A color reaction in an acidified, aqueous methylene blue solution containing chloroform can detect anionic surfactants in a water sample. Such a test is known as an MBAS assay (methylene blue active substances assay).

The MBAS assay cannot distinguish between specific surfactants, however. Some examples of anionic surfactants are carboxylates, phosphates, sulfates, and sulfonates.

Methylene blue value of fine aggregate

The methylene blue value is defined as the number of milliliter's standard methylene value solution decolorized 0.1 g of activated carbon (dry basis). Methylene blue value reflects the amount of clay minerals in aggregate samples. In materials science, methylene blue solution is successively added to fine aggregate which is being agitated in water. The presence of free dye solution can be checked with stain test on a filter paper.

Biological staining

In biology, methylene blue is used as a dye for a number of different staining procedures, such as Wright's stain and Jenner's stain. Since it is a temporary staining technique, methylene blue can also be used to examine RNA or DNA under the microscope or in a gel: as an example, a solution of methylene blue can be used to stain RNA on hybridization membranes in northern blotting to verify the amount of nucleic acid present. While methylene blue is not as sensitive as ethidium bromide, it is less toxic and it does not intercalate in nucleic acid chains, thus avoiding interference with nucleic acid retention on hybridization membranes or with the hybridization process itself.

It can also be used as an indicator to determine whether eukaryotic cells such as yeast are alive or dead. The methylene blue is reduced in viable cells, leaving them unstained. However dead cells are unable to reduce the oxidized methylene blue and the cells are stained blue. Methylene blue can interfere with the respiration of the yeast as it picks up hydrogen ions made during the process.

Aquaculture

Methylene blue is used in aquaculture and by tropical fish hobbyists as a treatment for fungal infections. It can also be effective in treating fish infected with ich although a combination of malachite green and formaldehyde is far more effective against the parasitic protozoa Ichthyophthirius multifiliis. It is usually used to protect newly laid fish eggs from being infected by fungus or bacteria. This is useful when the hobbyist wants to artificially hatch the fish eggs. Methylene blue is also very effective when used as part of a "medicated fish bath" for treatment of ammonia, nitrite, and cyanide poisoning as well as for topical and internal treatment of injured or sick fish as a "first response".

History

Methylene blue has been described as "the first fully synthetic drug used in medicine." Methylene blue was first prepared in 1876 by German chemist Heinrich Caro.

Its use in the treatment of malaria was pioneered by Paul Guttmann and Paul Ehrlich in 1891. During this period before the first World War, researchers like Ehrlich believed that drugs and dyes worked in the same way, by preferentially staining pathogens and possibly harming them. Changing the cell membrane of pathogens is in fact how various drugs work, so the theory was partially correct although far from complete. Methylene blue continued to be used in the second World War, where it was not well liked by soldiers, who observed, "Even at the loo, we see, we pee, navy blue." Antimalarial use of the drug has recently been revived. It was discovered to be an antidote to carbon monoxide poisoning and cyanide poisoning in 1933 by Matilda Brooks.

References

- Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 471. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 34. ISBN 9780857111562.

- Lillie RD (1977). H. J. Conn's Biological stains (9th ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 692p.

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- "Provayblue- methylene blue injection". DailyMed. 29 June 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Methylene Blue". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Lumeblue EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- "Lumeblue Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- Ahmad I, Aqil F (2008). New Strategies Combating Bacterial Infection. John Wiley & Sons. p. 91. ISBN 9783527622948. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Thomé SD, Petz LD (2002). "Hemolytic Anemia: Hereditary and Acquired". In Mazza J (ed.). Manual of Clinical Hematology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7817-2980-2.

- ^ Brent J. (2005). Critical care toxicology: diagnosis and management of the critically poisoned patient. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- "Hyophen: Indications, Side Effects, Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- "Prosed/DS: Indications, Side Effects, Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2024-04-20.

- ^ Brooks MM (1936). "Methylene blue as an antidote for cyanide and carbon monoxide poisoning". The Scientific Monthly. 43 (6): 585–586. Bibcode:1936SciMo..43..585M. JSTOR 16280.

- Hanzlik PJ (4 February 1933). "Methylene Blue As Antidote for Cyanide Poisoning". JAMA. 100 (5): 357. doi:10.1001/jama.1933.02740050053028.

- Hu X, Laguerre V, Packert D, Nakasone A, Moscinski L (2015). "A Simple and Efficient Method for Preparing Cell Slides and Staining without Using Cytocentrifuge and Cytoclips". International Journal of Cell Biology. 2015: 813216. doi:10.1155/2015/813216. PMC 4664808. PMID 26664363.

- Kiernan JA (2010). "Chapter 19: On Chemical Reactions and Staining Mechanisms" (PDF). In Kumar GL, Kiernan JA (eds.). Special Stains and H & E. Education Guide (Second ed.). Carpinteria, California: Dako North America, Inc. p. 172. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2012.

What is Giemsa's stain and how does it color blood cells, bacteria and chromosomes?

- Wilson TM (November 1907). "On the Chemistry and Staining Properties of Certain Derivatives of the Methylene Blue Group When Combined With Eosin". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 9 (6): 645–670. doi:10.1084/jem.9.6.645. PMC 2124692. PMID 19867116.

- Lewis SM, Bain BK, Bates I, Dacie JV (2006). Dacie and Lewis practical haematology (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-443-06660-3.

- Ehrlich P (1887). "Ueber die Methylenblau Reaktion der lebenden Nerven Substanz" [About the methylene blue reaction of the living nerve substance.] (PDF). Biologisches Zentralblatt [Biological Central Journal] (in German). 6: 214–224. cited by Baker JR (1958). Principles of biological microtechnique. A study of fixation and dyeing. London: Methuen.

- Wilson JG (July 1910). "Intra vitam staining with methylene blue". The Anatomical Record. 4 (7): 267–277. doi:10.1002/ar.1090040705. S2CID 86242668.

- Schabadasch A (January 1930). "Untersuchungen zur Methodik der Methylenblaufärbung des vegetativen Nervensystems" [Investigations on the methodology of methylene blue staining of the autonomic nervous system.]. Zeitschrift für Zellforschung und Mikroskopische Anatomie [Journal of Cell Research and Microscopic Anatomy] (in German). 10 (2): 221–243. doi:10.1007/BF02450696. S2CID 36940327.

- Zacks SI (1973). The Motor Endplate (2nd ed.). Huntington, NY: Krieger.

- Kiernan JA (June 1974). "Effects of metabolic inhibitors on vital staining with methylene blue". Histochemistry. 40 (1): 51–7. doi:10.1007/BF00490273. PMID 4136702. S2CID 23158612.

- Novella S (23 January 2008). "The ethics of deception in medicine". Science Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 2008-01-29. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- Clinical trial number NCT00214877 for "Methylene blue for cognitive dysfunction in bipolar disorder" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- Taylor GM, Avera RS, Strachan CC, Briggs CM, Medler JP, Pafford CM, Gant TB (February 2021). "Severe methemoglobinemia secondary to isobutyl nitrite toxicity: the case of the 'Gold Rush'". Oxford Medical Case Reports. 2021 (2): omaa136. doi:10.1093/omcr/omaa136. PMC 7885148. PMID 33614047.

- Modarai B, Kapadia YK, Kerins M, Terris J (May 2002). "Methylene blue: a treatment for severe methaemoglobinaemia secondary to misuse of amyl nitrite". Emergency Medicine Journal. 19 (3): 270–271. doi:10.1136/emj.19.3.270. PMC 1725875. PMID 11971852.

- Alici-Evcimen Y, Breitbart WS (October 2007). "Ifosfamide neuropsychiatric toxicity in patients with cancer". Psycho-Oncology. 16 (10): 956–960. doi:10.1002/pon.1161. PMID 17278152. S2CID 27433170.

- Patel PN (February 2006). "Methylene blue for management of Ifosfamide-induced encephalopathy". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (2): 299–303. doi:10.1345/aph.1G114. PMID 16391008. S2CID 21124635.

- Dufour C, Grill J, Sabouraud P, Behar C, Munzer M, Motte J, et al. (February 2006). "". Archives de Pédiatrie (in French). 13 (2): 140–145. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2005.10.021. PMID 16364615.

- Aeschlimann C, Cerny T, Küpfer A (December 1996). "Inhibition of (mono)amine oxidase activity and prevention of ifosfamide encephalopathy by methylene blue". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 24 (12): 1336–1339. PMID 8971139.

- Jang DH, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS (September 2013). "Methylene blue for distributive shock: a potential new use of an old antidote". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 9 (3): 242–249. doi:10.1007/s13181-013-0298-7. PMC 3770994. PMID 23580172.

- Paciullo CA, McMahon Horner D, Hatton KW, Flynn JD (July 2010). "Methylene blue for the treatment of septic shock". Pharmacotherapy. 30 (7): 702–715. doi:10.1592/phco.30.7.702. PMID 20575634. S2CID 759538.

- Hosseinian L, Weiner M, Levin MA, Fischer GW (January 2016). "Methylene Blue: Magic Bullet for Vasoplegia?". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 122 (1): 194–201. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001045. PMID 26678471. S2CID 26114442.

- Levin RL, Degrange MA, Bruno GF, Del Mazo CD, Taborda DJ, Griotti JJ, Boullon FJ (February 2004). "Methylene blue reduces mortality and morbidity in vasoplegic patients after cardiac surgery". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 77 (2): 496–499. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01510-8. PMID 14759425.

- Leite EG, Ronald A, Rodrigues AJ, Evora PR (December 2006). "Is methylene blue of benefit in treating adult patients who develop catecholamine-resistant vasoplegic syndrome during cardiac surgery?". Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 5 (6): 774–8. doi:10.1510/icvts.2006.134726. PMID 17670710. S2CID 30259038.

- Stawicki SP, Sims C, Sarani B, Grossman MD, Gracias VH (May 2008). "Methylene blue and vasoplegia: who, when, and how?". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 8 (5): 472–490. doi:10.2174/138955708784223477. PMID 18473936. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Fadhlillah F, Patil S (August 2018). "Pharmacological and mechanical management of calcium channel blocker toxicity". BMJ Case Reports. 2018: bcr2018225324. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-225324. PMC 6119390. PMID 30150339.

- Saha BK, Bonnier A, Chong W (December 2020). "Rapid reversal of vasoplegia with methylene blue in calcium channel blocker poisoning". African Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1016/j.afjem.2020.06.014. PMC 7700985. PMID 33299766.

- Aggarwal N, Kupfer Y, Seneviratne C, Tessler S (January 2013). "Methylene blue reverses recalcitrant shock in β-blocker and calcium channel blocker overdose". BMJ Case Reports. 2013: bcr2012007402. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007402. PMC 3604019. PMID 23334490.

- Pellegrini JR, Munshi R, Tiwana MS, Abraham T, Tahir H, Sayedy N, Iqbal J (October 2021). ""Feeling the Blues": A Case of Calcium Channel Blocker Overdose Managed With Methylene Blue". Cureus. 13 (10): e19114. doi:10.7759/cureus.19114. PMC 8627593. PMID 34868762.

- Ahmed S, Barnes S (2019). "Hemodynamic improvement using methylene blue after calcium channel blocker overdose". World Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10 (1): 55–58. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2019.01.009. PMC 6264975. PMID 30598720.

- Burkes R, Wendorf G (July 2015). "A multifaceted approach to calcium channel blocker overdose: a case report and literature review". Clinical Case Reports. 3 (7): 566–569. doi:10.1002/ccr3.300. PMC 4527798. PMID 26273444.

- Chudow M, Ferguson K (April 2018). "A Case of Severe, Refractory Hypotension After Amlodipine Overdose". Cardiovascular Toxicology. 18 (2): 192–197. doi:10.1007/s12012-017-9419-x. PMID 28688059. S2CID 3713149.

- Jang DH, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS (December 2011). "Methylene blue in the treatment of refractory shock from an amlodipine overdose". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 58 (6): 565–567. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.02.025. PMID 21546119.

- Laes JR, Williams DM, Cole JB (December 2015). "Improvement in Hemodynamics After Methylene Blue Administration in Drug-Induced Vasodilatory Shock: A Case Report". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 11 (4): 460–463. doi:10.1007/s13181-015-0500-1. PMC 4675606. PMID 26310944.

- ^ Mokhlesi B, Leikin JB, Murray P, Corbridge TC (March 2003). "Adult toxicology in critical care: Part II: specific poisonings". Chest. 123 (3): 897–922. doi:10.1378/chest.123.3.897. PMID 12628894. S2CID 9962335.

- ^ Harvey JW, Keitt AS (May 1983). "Studies of the efficacy and potential hazards of methylene blue therapy in aniline-induced methaemoglobinaemia". British Journal of Haematology. 54 (1): 29–41. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.1983.tb02064.x. PMID 6849836. S2CID 19304915.

- Ramsay RR, Dunford C, Gillman PK (November 2007). "Methylene blue and serotonin toxicity: inhibition of monoamine oxidase A (MAO A) confirms a theoretical prediction". British Journal of Pharmacology. 152 (6): 946–951. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707430. PMC 2078225. PMID 17721552.

- Gillman PK (October 2006). "Methylene blue implicated in potentially fatal serotonin toxicity". Anaesthesia. 61 (10): 1013–1014. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04808.x. PMID 16978328. S2CID 45063314.

- Rosen PJ, Johnson C, McGehee WG, Beutler E (July 1971). "Failure of methylene blue treatment in toxic methemoglobinemia. Association with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". Annals of Internal Medicine. 75 (1): 83–86. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-75-1-83. PMID 5091568.

- Berneth H (2012). "Azine Dyes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_213.pub3. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Maleki A, Nematollahi D (December 2009). "An efficient electrochemical method for the synthesis of methylene blue". Electrochemistry Communications. 11 (12): 2261–2264. doi:10.1016/j.elecom.2009.09.040.

- Cenens J, Schoonheydt RA (1988). "Visible spectroscopy of methylene blue on hectorite, laponite B, and barasym in aqueous suspension". Clays and Clay Minerals. 36 (3): 214–224. Bibcode:1988CCM....36..214C. doi:10.1346/ccmn.1988.0360302. S2CID 3851037.

- Cook AG, Tolliver RM, Williams JE (February 1994). "The Blue Bottle experiment revisited: How Blue? How Sweet?". Journal of Chemical Education. 71 (2): 160. Bibcode:1994JChEd..71..160C. doi:10.1021/ed071p160.

- ^ Anderson L, Wittkopp SM, Painter CJ, Liegel JJ, Schreiner R, Bell JA, Shakhashiri BZ (9 October 2012). "What is happening when the Blue Bottle bleaches: An Investigation of the methylene blue-catalyzed air oxidation of glucose". Journal of Chemical Education. 89 (11): 1425–1431. Bibcode:2012JChEd..89.1425A. doi:10.1021/ed200511d.

- Rajchakit U, Limpanuparb T (9 August 2016). "Rapid Blue Bottle experiment: Autoxidation of benzoin catalyzed by redox indicators". Journal of Chemical Education. 93 (8): 1490–1494. Bibcode:2016JChEd..93.1490R. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00018.

- ^ Harvey EN (March 1919). "The relation between the oxygen concentration and rate of reduction of methylene blue by milk". The Journal of General Physiology. 1 (4): 415–419. doi:10.1085/jgp.1.4.415. PMC 2140316. PMID 19871757.

- Jakubowski H (2016). "Chapter 8: Oxidation/Phosphorylation B: Oxidative Enzymes". Biochemistry Online.

- ^ Siegel Lewis M (1965-04-01). "A direct microdetermination for sulfide". Analytical Biochemistry. 11 (1): 126–132. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(65)90051-5. ISSN 0003-2697. PMID 14328633.

- "Analytik und Probenvorbereitung". Darmstadt, Germany: Merck KGaA. Archived from the original on 2007-03-15.

- ^ Thornton H (May 1930). "Studies on Oxidation-Reduction in Milk: The Methylene Blue Reduction Test". Journal of Dairy Science. 13 (3). Elsevier Inc.: 221–245. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(30)93520-5.

- "Test Methods for Activated Carbon" (PDF). European Council of Chemical Manufacturers' Federations. April 1986.

- Standard Test Method for Rapid Determination of the Methylene Blue Value for Fine Aggregate or Mineral Filler Using a Colorimeter (Report). West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM (American Society for Testing and Material) International. 7 July 2020. doi:10.1520/C1777-20. ASTM C1777. Archived from the original on 2014-02-28.

- Standing Committee on Concrete Technology (SCCT) (May 2013). "Construction Standard CS3:2013 – Aggregates for Concrete" (PDF). The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

- "Methylene Blue". 3 Little Fish Sdn Bhd. Kelana Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. 10 September 2021.

- Heinrich Caro was an employee of the Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik, BASF, of Mannheim, Germany, which received a patent for methylene blue in 1877:

- Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik, BASF, of Mannheim, Germany, "Verfahren zur Darstellung blauer Farbstoffe aus Dimethylanilin und anderen tertiaren aromatischen Monaminen" , Deutsches Reich Patent no. 1886 (issued: December 15, 1877).

- Available on-line at: Friedlaender P (1888). Fortschritte der Theerfarbenfabrikation und verwandter Industriezweige [Progress of the manufacture of coal-tar dyes and related branches of industry] (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin, Germany: Julius Springer. pp. 247–249. Archived from the original on 2015-03-21. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- Coulibaly B, Zoungrana A, Mockenhaupt FP, Schirmer RH, Klose C, Mansmann U, et al. (2009). "Strong gametocytocidal effect of methylene blue-based combination therapy against falciparum malaria: a randomised controlled trial". PLOS ONE. 4 (5): e5318. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5318C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005318. PMC 2673582. PMID 19415120.

- Brooks MM (January 1933). "Methylene Blue As Antidote for Cyanide and Carbon Monoxide Poisoning". JAMA. 100: 59. doi:10.1001/jama.1933.02740010061028.

External links

- "Methylene blue". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Methylene blue test". MedlinePlus.

| Antidotes (V03AB) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nervous system |

| ||||||||||||||

| Circulatory system |

| ||||||||||||||

| Other |

| ||||||||||||||

| Emetic | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Microbial and histological stains | |

|---|---|

| Iron/hemosiderin | |

| Lipids | |

| Carbohydrates | |

| Amyloid | |

| Bacteria | |

| Connective tissue | |

| Other | |

| Tissue stainability | |

| Monoamine metabolism modulators | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specific |

| ||||||||||

| Phenethylamines (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine) |

| ||||||||||

| Tryptamines (serotonin, melatonin) |

| ||||||||||

| Histamine |

| ||||||||||

| See also: Receptor/signaling modulators • Adrenergics • Dopaminergics • Melatonergics • Serotonergics • Monoamine reuptake inhibitors • Monoamine releasing agents • Monoamine neurotoxins | |||||||||||

| Tricyclics | |

|---|---|

| Classes | |

| Antidepressants (Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)) |

|

| Antihistamines |

|

| Antipsychotics |

|

| Anticonvulsants | |

| Anticholinergics | |

| Others | |